感染性眼内炎的诊断和治疗

2022-05-07张瑜袁晓玲马懿辰陆肇曾

张瑜 袁晓玲 马懿辰 陆肇曾

摘 要 感染性眼内炎是病原体侵入眼内組织并在眼组织内生长、繁殖所引起的炎性反应,可累及和破坏眼内多种组织,严重损害患者的视功能。感染性眼内炎依感染源可分为内源性和外源性两类,依病原体可分为细菌性、病毒性和真菌性等亚类。本文根据感染性眼内炎的研究现状,就其发病率、病因学、病原学、诊断、病原学检测和治疗原则等作一概要介绍,以提高同人对此疾病的认识,为相关临床实践提供参考。

关键词 眼内炎 白内障手术 玻璃体切割术

中图分类号:R77 文献标志码:A 文章编号:1006-1533(2022)07-0007-06

引用本文 张瑜, 袁晓玲, 马懿辰, 等. 感染性眼内炎的诊断和治疗[J]. 上海医药, 2022, 43(7): 7-12; 19.

Diagnosis and treatment of infectious endophthalmitis

ZHANG Yu, YUAN Xiaoling, MA Yichen, LU Zhaozeng

(Department of Ophthalmology, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China)

ABSTRACT Infectious endophthalmitis is an inflammatory reaction caused by pathogens invading the ocular tissue and growing and reproducing in the ocular tissue and can involve and destroy a variety of ocular tissues and seriously damage the visual function of patients. Infectious endophthalmitis can be divided into two types: endogenous and exogenous according to the source of infection and bacterial, viral and fungal subtypes according to the pathogen. Based on the current research situation, this article briefly introduces the incidence, etiology, diagnosis, pathogenic detection and treatment principles of infectious endophthalmitis, so as to improve the understanding of the disease and provide a reference for clinical practice.

KEy wORDS infectious endophthalmitis; cataract surgery; pars plana vitrectomy

眼内炎(endophthalmitis)是指致炎物质进入眼内引起的眼部炎性反应,根据病因分为感染性和非感染性两大类。其中,感染性眼内炎与病原体感染相关,而非感染性眼内炎则是由机体免疫系统紊乱导致的机体对自身抗原的免疫应答所引起的眼部炎性反应。感染性眼内炎因病原体侵入眼内组织并在眼组织内迅速生长、繁殖,可累及和破坏眼内多种组织,甚至发展为眼球周围炎,常导致患者视力损害甚至丧失。鉴于感染性眼内炎病情发展迅速,预后较差,是严重的致盲性眼病,故临床上所言眼内炎一般都指感染性眼内炎,本文下述部分亦将如此。

眼内炎可分为外源性和内源性两类。外源性眼内炎是在眼球壁出现破口后病原体侵入而发生的,主要有手术后和外伤后两型。内源性眼内炎则由体内其他部位的病原体扩散至眼内引起。眼内炎的最常见病原体是细菌,但其也可由真菌、寄生虫和病毒引起。

眼内炎发展迅速,对患者视功能影响严重,临床医生及时诊断非常重要:首先要确定眼内炎的性质,其次须确定其病原体是细菌、真菌、病毒还是其他。随着现代医学发展,眼内炎的治愈率逐年提高,但眼内炎仍是一种严重的致盲性眼病。了解眼内炎的病因学、病原学特征和诊断方法、治疗原则,对于提高眼内炎诊治水平和促进临床防盲致盲工作具有重要的意义。

1 发病率

对于外源性眼内炎,有研究报告,内眼手术后的急性眼内炎发病率为0.036% ~ 0.36%[1-3],其中美国的白内障术后眼内炎发病率为0.04%[2]。目前,不同国家的白内障术后眼内炎发病率为0.012% ~ 1.3%[3]。青光眼术后滤过泡相关性感染引起的眼内炎发病率为0.45% ~ 1.7%[4]。随着玻璃体切割术(pars plana vitrectomy, PPV)的应用趋广,PPV后眼内炎患者也渐渐增多。一项对148 643例玻璃体手术后患者的系统回顾性研究发现,玻璃体切除术后眼内炎发病率为0.046%[5]。由于抗血管内皮生长因子(vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF)和糖皮质激素等药物在眼科的大量应用,玻璃体腔注射后眼内炎患者亦有增多趋势[6-8]。这种眼内炎的发病率与注射眼数相关,而与总注射次数无关,即每次注射后发生眼内炎的概率非常低。回顾性研究显示,玻璃体腔注射抗VEGF药物患者的眼内炎发病率通常≤0.05%[9-10]。不过,玻璃体腔注射曲安奈徳后的眼内炎发病率较高(0.87%)[11]。开放性眼外伤后的眼内炎发病率为6.8%[12],另有研究发现可高达 15% ~ 30%[13]。

内源性眼内炎的发病率为0.04% ~ 0.4%,通常發生在系统性疾病或免疫功能低下并伴有相关危险因素患者中[14],危险因素包括静脉注射毒品使用(intravenous drug use, IVDU)、糖尿病、免疫抑制、恶性肿瘤、长期住院和深静脉置管等。

2 病因学、病原学

外源性眼内炎的病因可根据疾病的临床特征和患者的既往史来推测[15-17](表1)。万磊等[18]分析了531例化脓性眼内炎患者的致病因素和病原学特征,发现眼外伤(60.1%)是眼内炎的主要致病因素,其次为内眼手术(19.0%)和感染性角膜炎(17.1%)。革兰阳性菌(54.0%)是导致化脓性眼内炎的主要病原体,其中以表皮葡萄球菌(25.0%)最常见;其他病原体主要为真菌(29.5%),其中以曲霉和镰刀菌较常见。近年来由玻璃体腔注射引起的眼内炎患者增多,可能与现今眼科广泛应用抗VEGF等药物及其玻璃体腔注射频次增高有关。这种眼内炎通常由凝固酶阴性的葡萄球菌引起[19-20]。青光眼术后眼内炎与患者较为年轻、滤过泡薄而无血管、滤过泡炎,以及手术期间使用抗代谢药物和长期使用抗菌药物滴眼液有关,最常见的病原体是凝固酶阴性的葡萄球菌和链球菌[21]。有部分眼内炎与角膜炎相关,而角膜炎的主要病原体有革兰阴性菌、金黄色葡萄球菌、链球菌和各种真菌等[22]。镰刀菌性角膜炎的发生与佩戴软性隐形眼镜有关[23]。有研究显示与镰刀菌性角膜炎相关的眼内炎渐多[24]。外伤性眼内炎通常由毒力较强的病原体引起,如蜡样芽孢杆菌等[25]。

内源性眼内炎的病原体多为细菌或真菌[26],其中最常见的致病细菌是克雷伯菌和链球菌[27-28],最常见的致病真菌是白色假丝酵母和曲霉[26]。近年来,泰国的肺炎克雷伯菌性眼内炎发病率明显增高[29]。我们在临床实践中也发现,细菌性眼内炎,尤其是肺炎克雷伯菌所致眼内炎,在眼内炎中的占比较高。内源性眼内炎与IVDU相关的报告亦越来越多[14]。一项回顾性研究发现,在与IVDU相关的30例眼内炎患者(32只眼)中,59%患眼的病原体为真菌,16%患眼的病原体为细菌[30]。

在临床上,细菌性和真菌性眼内炎主要表现为化脓性眼内炎。另外,有些视网膜炎、视网膜脉络膜炎、视网膜血管炎和急性视网膜坏死综合征,甚至青光眼睫状体炎综合征,还有人类免疫缺陷病毒感染患者的巨细胞病毒性视网膜炎,在患者眼内液(房水或玻璃体液)中均可检测到病毒的存在[31-32],它们虽然没有被诊断为眼内炎,但实际上应该归属于病毒性眼内炎。应用聚合酶链式反应(polymerase chain reaction, PCR)和二代测序技术(next-generation sequencing, NGS)方法对眼内液进行检测,可提高这些病毒性眼内炎的诊断率。

3 鉴别诊断

眼内炎,特别是白内障术后眼内炎的诊断,须与中毒性眼前节综合征(toxic anterior segment syndrome, TASS)、晶状体碎片残留、葡萄膜炎、曲安奈徳微粒和陈旧玻璃体积血等相鉴别。无菌性炎性反应可能继发于残留的晶状体碎片或手术中引入的异物。残留皮质碎片可能较残留核块碎片引起更严重的炎性反应,偶可导致前房积脓[33]。TASS是一种中重度无菌性炎性反应,通常发生在内眼手术后12 ~ 48 h内,典型症状包括角膜水肿、前房积脓、瞳孔光反射消失和眼压增高[34],可能由术中或术后接触外来物质引起,包括人工晶状体、药物软膏等[35]。在某些患者中,TASS可能很难与感染性眼内炎相鉴别。通常,TASS出现的时间要早于感染性眼内炎,体征也仅限于眼前节。TASS患者的角膜水肿程度可能与炎性反应程度不成比例。

前房内的非感染性物质也可能与眼内炎的表现类似。例如,曲安奈德微粒可向前房迁移,从而形成假性前房积脓[36]。陈旧的眼内积血易与感染性物质混淆[37]。玻璃体腔注射可能与不明原因引起的无菌性眼内炎性反应相关[38]。多项病例报告显示,无菌性眼内炎性反应常发生在使用同一批次玻璃体腔注射药物治疗的患者中[39-40]。另有研究发现,与使用雷珠单抗治疗相比,使用贝伐珠单抗治疗的无菌性眼内炎性反应发生率更高[41]。

4 病原学检测

病原学检测有利于明确眼内炎的性质,对治疗药物的选择具有重要指导意义。因此,对于眼内炎患者,眼内液的获取和检测至关重要。

1)眼内液的获取

要进行眼内炎病原学检测,需先获取眼内液样本。研究发现,与房水样本相比,玻璃体液样本更可能产生阳性结果[42]。玻璃体液样本可通过针刺活检(玻璃体穿刺抽液)或在PPV过程中获得。

2)眼内液的检测

(1)涂片染色、病原体培养和药敏试验

对眼内液样本进行涂片染色、病原体培养和药敏试验,这对于高度疑为眼内炎或结核性葡萄膜炎患者的诊断具有十分重要的意义。对高度疑为内源性眼内炎患者,需对其眼内液样本进行革兰染色、细菌/真菌培养和药敏试验,药敏试验的结果可指导临床选择合适的抗感染药物对患者进行治疗。病原体培养的阳性率高于涂片染色检查,但涂片染色检查能迅速获得结果,且可用于与晶状体蛋白过敏等非感染性眼内炎的鉴别诊断。不过,涂片染色检查和病原体培养不能用于诊断病毒所致眼内感染。

根据获取的样本量和患者临床情况(如急诊还是门诊等),选择相应的病原体培养方法[43]。其中,传统方法是直接将样本接种于培养基上。培养基可含有5%的血琼脂,以培养最常见的细菌和真菌。巧克力琼脂用于培养淋球菌和流感嗜血杆菌等;Sabouraud琼脂用于培养真菌;巯基乙酸肉汤用于培养厌氧菌。另外,急诊情况下也可将样本注入血培养瓶中[44]。对于高度疑为眼内结核杆菌感染的患者,还需进行结核杆菌抗酸染色及培养。Davis[45]的研究显示,与最终的临床诊断相比,依据眼内液细菌/真菌培养结果诊断的正确率达96%。因此,病原体培养已被视为眼内感染诊断的“金标准”。但需注意的是,由于病原体培养所需时间长,样本转运过程(如转运时间、样本储存条件等)对培养结果的影响较大。

(2)PCR法

眼內炎临床诊断率的提高与检测技术的发展密切相关。多项研究显示,使用PCR法检测疑为细菌性或真菌性眼内炎患者玻璃体液样本的结果与病原体培养结果的一致性接近100%,而PCR法检测的灵敏度更高[46-48]。有研究者推测,PCR法检测最终将替代病原体培养和药敏试验(通过扩增已知位点来确定对抗生素的耐药性)法[49],且其能够检测出未被怀疑或未知的病原体[50-51]。但PCR法检测也有缺陷,其检测每一种病原体及其亚型都需要有针对性的PCR探针,实际应用受限于PCR探针是否已开发成功或有怀疑倾向的病原体,用于不明原因感染的病原体检测则无异于大海捞针。PCR法目前多用于病毒性感染病原体如巨细胞病毒、疱疹病毒等的检测。

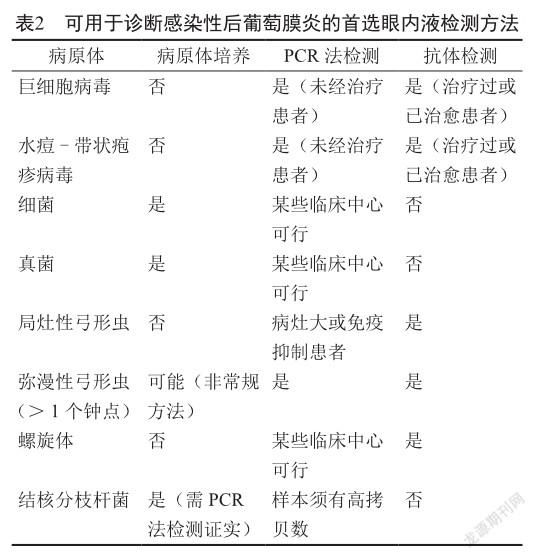

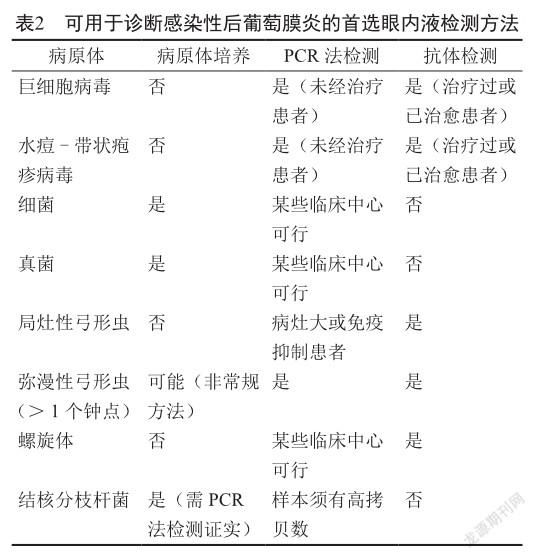

一些研究分析了病原体培养阴性(主要是病毒性和原虫性脉络膜视网膜炎)患者房水或玻璃体液样本的PCR法检测情况,结果发现使用房水样本就可进行眼内液的PCR法检测[52-54]。结核性脉络膜视网膜炎也可通过PCR法检测得到证实[55]。Mantoux和干扰素-γ释放试验有助于结核性脉络膜视网膜炎的诊断。房水中亦可检测到眼内梅毒抗体[56],而血清学试验有助于梅毒的诊断。Davis[45]总结了可用于诊断感染性后葡萄膜炎的首选眼内液检测方法(表2)。

(3)视网膜活检等

某些情况下需对患者进行进一步的视网膜活检,以明确诊断。若活检见巨细胞性包涵体或弓形虫速殖子,可确诊为弓形虫视网膜炎。如疑为单纯性疱疹或水痘-带状疱疹病毒眼内感染,建议进行免疫组织化学检查予以确认。若能获得活检组织,则可用载玻片进行选择性抗体染色或通过原位杂交技术进行处理[57]。肽核酸-荧光原位杂交法是一种较有前途的眼内炎诊断方法[58],但目前尚未用于临床实践。

(4)NGS法

新技术的发展使临床医生能够通过检测眼内液来获知眼内炎的病原体,如细菌、真菌、病毒、寄生虫、螺旋体等。使用基因芯片或测序方法可以检测出包括上述病原体在内的大多数病原体。目前,二代高通量测序技术对眼内液病原体的检测范围非常广泛,包括7 000余种病毒、3 000余种细菌、200余种真菌、150余种寄生虫、80余种分枝杆菌和70余种的支原体、衣原体,其能通过智能计算和数据分析,报告疑似病原体的种属信息,具有灵敏度高、特异性强和检测速度快(最快仅需4 ~ 6 h)等优点[59-61],可为临床诊断提供更精准和全面的参考。我院就曾通过NGS法协助诊断猪疱疹病毒引起的人类眼内炎[62],为对患者进一步治疗提供了精准的方向。但NGS法检测亦有其缺陷,即不能进行进一步的药敏试验。

5 治疗原则

一旦确诊为眼内炎,即须尽早进行手术及抗感染治疗。若暂无条件施行手术,可先进行玻璃体腔注射药物治疗。应根据病原体的种属如细菌、真菌或病毒等给予患者有效的抗感染治疗。聚维酮碘术前消毒、玻璃体腔注射药物、PPV、硅油和新型抗菌药物的应用能使眼内炎患者获得更好的预后。玻璃体腔注射药物治疗细菌性眼内炎时,可选择万古霉素(1.0 mg/0.1 mL)-头孢他啶(2.25 mg/0.1 mL)或阿米卡星(0.4 mg/0.1 mL);治疗真菌性眼内炎时,可选择两性霉素B(0.005 mg/0.1 mL)或伏立康唑(0.1 mg/0.2 mL)[63];治疗病毒性眼内炎如巨细胞病毒性视网膜炎时,可选择更昔洛韦(3 mg/0.1 mL)和/或膦甲酸钠(2.4 mg/0.1 mL)[31-32]。需指出的是,对于病毒引起的眼内感染治疗的药物剂量及疗程,目前尚无国际共识,有待进一步的临床探索。

在进行眼部手术和玻璃体腔注射药物治疗的同时,对患者及时给予全身抗感染治疗也非常重要。对细菌性眼内炎,特别是白内障术后严重急性化脓性眼内炎患者,应全身使用与玻璃体腔注射的抗菌药物相同的抗菌药物治疗,如万古霉素、头孢他啶或阿米卡星;对真菌性眼内炎患者,也需同时给予全身抗真菌治疗,一般推荐使用两性霉素B、伏立康唑或氟胞嘧啶等治疗6 ~ 8周[64]。注意根据药敏试验结果调整所用抗菌药物。对病毒性眼内炎患者,建议使用更昔洛韦或伐昔洛韦等进行治疗,治疗时间可能需2 ~ 3个月。急性细菌性或真菌性化脓性眼内炎的病情凶险紧急,延迟治疗会严重影响预后,故须尽早对患者进行手术、玻璃体腔注射和全身用药治疗。开始时给予上述经验治疗,再根据药敏试验结果调整所用抗菌药物。对病毒性眼内炎的治疗,通常在获知眼内液检测结果后再决定治疗用药。

6 结语

综上所述,眼内炎的病因多样,表现各异,临床医生需有足够的知识和经验才能诊断和治疗。病原学检测是眼内炎诊断的非常重要的依据。眼内液检测不仅能够辅助临床医生诊断,且还可为临床医生制定个体化的治疗方案提供精准的依据,从而迅速挽救患者的视功能。

参考文献

[1] Kamalarajah S, Silvestri G, Sharma N, et al. Surveillance of endophthalmitis following cataract surgery in the UK [J]. Eye(Lond), 2004, 18(6): 580-587.

[2] Miller JJ, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, et al. Acute-onset endophthalmitis after cataract surgery (2000-2004): incidence, clinical settings, and visual acuity outcomes after treatment[J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 2005, 139(6): 983-987.

[3] Cao H, Zhang L, Li L, et al. Risk factors for acute endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(8): e71731.

[4] Vaziri K, Kishor K, Schwartz SG, et al. Incidence of blebassociated endophthalmitis in the United States [J]. Clin Ophthalmol, 2015, 9: 317-322.

[5] Govetto A, Virgili G, Menchini F, et al. A systematic review of endophthalmitis after microincisional versus 20-gauge vitrectomy [J]. Ophthalmology, 2013, 120(11): 2286-2291.

[6] Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET Jr, et al. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration[J]. N Engl J Med, 2004, 351(27): 2805-2816.

[7] Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006, 355(14): 1432-1444.

[8] Heier JS, Brown DM, Chong V, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept(VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration [J]. Ophthalmology, 2012, 119(12): 2537-2548.

[9] Rasmussen A, Bloch SB, Fuchs J, et al. A 4-year longitudinal study of 555 patients treated with ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration [J]. Ophthalmology, 2013, 120(12): 2630-2636.

[10] Mithal K, Mathai A, Pathengay A, et al. Endophthalmitis following intravitreal anti-VEGF injections in ambulatory surgical centre facility: incidence, management and outcome[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2013, 97(12): 1609-1612.

[11] Moshfeghi DM, Kaiser PK, Scott IU, et al. Acute endophthalmitis following intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection [J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 2003, 136(5): 791-796.

[12] Essex RW, Yi Q, Charles PG, et al. Post-traumatic endophthalmitis [J]. Ophthalmology, 2004, 111(11): 2015-2022.

[13] Banker TP, McClellan AJ, Wilson BD, et al. Culture-positive endophthalmitis after open globe injuries with and without retained intraocular foreign bodies [J]. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina, 2017, 48(8): 632-637.

[14] Relhan N, Schwartz SG, Flynn HW Jr. Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis: an increasing problem among intravenous drug users [J]. JAMA, 2017, 318(8): 741-742.

[15] Bannerman TL, Rhoden DL, McAllister SK, et al. The source of coagulase-negative Staphylococci in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. A comparison of eyelid and intraocular isolates using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis [J]. Arch Ophthalmol, 1997, 115(3): 357-361.

[16] Clark WL, Kaiser PK, Flynn HW Jr, et al. Treatment strategies and visual acuity outcomes in chronic postoperative Propionibacterium acnes endophthalmitis [J]. Ophthalmology, 1999, 106(9): 1665-1670.

[17] Scott IU, Lieb DF, Flynn HW Jr, et al. Endophthalmitis caused by Mycobacterium chelonae: selection of antibiotics and outcomes of treatment [J]. Arch Ophthalmol, 2003, 121(4): 573-576.

[18] 萬磊, 陈楠, 张静, 等. 531例化脓性眼内炎患者的致病因素和病原学特征分析[J]. 中华眼底病杂志, 2019, 35(2): 181-186.

[19] Chen E, Lin MY, Cox J, et al. Endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection: the importance of viridans Streptococci[J]. Retina, 2011, 31(8): 1525-1533.

[20] McCannel CA. Meta-analysis of endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents: causative organisms and possible prevention strategies[J]. Retina, 2011, 31(4): 654-661.

[21] Medina CA, Butler MR, Deobhakta AA, et al. Endophthalmitis associated with glaucoma drainage implants[J]. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina, 2016, 47(6): 563-569.

[22] Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Feuer W, et al. Endophthalmitis associated with microbial keratitis [J]. Ophthalmology, 1996, 103(11): 1864-1870.

[23] Chang DC, Grant GB, ODonnell K, et al. Multistate outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solution [J]. JAMA, 2006, 296(8): 953-963.

[24] Dursun D, Fernandez V, Miller D, et al. Advanced Fusarium keratitis progressing to endophthalmitis [J]. Cornea, 2003, 22(4): 300-303.

[25] Vahey JB, Flynn HW Jr. Results in the management of Bacillus endophthalmitis [J]. Ophthalmic Surg, 1991, 22(11): 681-686.

[26] Schiedler V, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, et al. Culture-proven endogenous endophthalmitis: clinical features and visual acuity outcomes [J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 2004, 137(4): 725-731.

[27] Miller JJ, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, et al. Endophthalmitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae [J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 2004, 138(2): 231-236.

[28] Scott IU, Matharoo N, Flynn HW Jr, et al. Endophthalmitis caused by Klebsiella species [J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 2004, 138(4): 662-663.

[29] Lourthai P, Choopong P, Dhirachaikulpanich D, et al. Visual outcome of endogenous endophthalmitis in Thailand [J]. Sci Rep, 2021, 11(1): 14313.

[30] Modjtahedi BS, Finn AP, Eliott D. Association of endogenous endophthalmitis with intravenous drug use: an emerging public health challenge [J]. JAMA Ophthalmol, 2017, 135(12): 1457.

[31] Fan JJ, Tao Y, Hwang DK. Comparison of intravitreal ganciclovir monotherapy and combination with foscarnet as initial therapy for cytomegalovirus retinitis [J]. Int J Ophthalmol, 2018, 11(10): 1638-1642.

[32] Qian Z, Li H, Tao Y, et al. Initial intravitreal injection of highdose ganciclovir for cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV-negative patients [J]. BMC Ophthalmol, 2018, 18(1): 314.

[33] Irvine WD, Flynn HW Jr, Murray TG, et al. Retained lens fragments after phacoemulsification manifesting as marked intraocular inflammation with hypopyon [J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 1992, 114(5): 610-614.

[34] Mamalis N. Toxic anterior segment syndrome [J]. J Cataract Refract Surg, 2006, 32(2): 181-182.

[35] Werner L, Sher JH, Taylor JR, et al. Toxic anterior segment syndrome and possible association with ointment in the anterior chamber following cataract surgery [J]. J Cataract Refract Surg, 2006, 32(2): 227-235.

[36] Moshfeghi AA, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, et al. Pseudohypopyon after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection for cystoid macular edema [J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 2004, 138(3): 489-492.

[37] Nahas Z, Shienbaum G, Smiddy WE, et al. Hypopyon and pseudoendophthalmitis 1 month after vitrectomy for retinal detachment with subretinal hemorrhage [J]. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina, 2013, 44(3): 281-283.

[38] Hahn P, Kim JE, Stinnett S, et al. Aflibercept-related sterile inflammation [J]. Ophthalmology, 2013, 120(5): 1100-1101. e1-e5.

[39] Entezari M, Ramezani A, Ahmadieh H, et al. Batch-related sterile endophthalmitis following intravitreal injection of bevacizumab [J]. Indian J Ophthalmol, 2014, 62(4): 468-471.

[40] Yamashiro K, Tsujikawa A, Miyamoto K, et al. Sterile endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab obtained from a single batch [J]. Retina, 2010, 30(3): 485-490.

[41] Sharma S, Johnson D, Abouammoh M, et al. Rate of serious adverse effects in a series of bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections [J]. Can J Ophthalmol, 2012, 47(3): 275-279.

[42] Donahue SP, Kowalski RP, Jewart BH, et al. Vitreous cultures in suspected endophthalmitis. Biopsy or vitrectomy? [J]. Ophthalmology, 1993, 100(4): 452-455.

[43] Johnson MW, Doft BH, Kelsey SF, et al. The Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Relationship between clinical presentation and microbiologic spectrum [J]. Ophthalmology, 1997, 104(2): 261-272.

[44] Eser I, Kapran Z, Altan T, et al. The use of blood culture bottles in endophthalmitis [J]. Retina, 2007, 27(7): 971-973.

[45] Davis JL. Diagnostic dilemmas in retinitis and endophthalmitis [J]. Eye (Lond), 2012, 26(2): 194-201.

[46] Bispo PJ, de Melo GB, Hofling-Lima AL, et al. Detection and gram discrimination of bacterial pathogens from aqueous and vitreous humor using real-time PCR assays [J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2011, 52(2): 873-881.

[47] Sugita S, Shimizu N, Watanabe K, et al. Diagnosis of bacterial endophthalmitis by broad-range quantitative PCR [J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2011, 95(3): 345-349.

[48] Seal D, Reischl U, Behr A, et al. Laboratory diagnosis of endophthalmitis: comparison of microbiology and molecular methods in the European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons multicenter study and susceptibility testing [J]. J Cataract Refract Surg, 2008, 34(9): 1439-1450.

[49] Huletsky A, Giroux R, Rossbach V, et al. New real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus directly from specimens containing a mixture of Staphylococci [J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2004, 42(5): 1875-1884.

[50] Drancourt M, Berger P, Terrada C, et al. High prevalence of fastidious bacteria in 1 520 cases of uveitis of unknown etiology [J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2008, 87(3): 167-176.

[51] Chiquet C, Bodaghi B, Mougin C, et al. Acute retinal necrosis diagnosed in a child with chronic panuveitis [J]. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2006, 244(9): 1206-1208.

[52] Harper TW, Miller D, Schiffman JC, et al. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of aqueous and vitreous specimens in the diagnosis of posterior segment infectious uveitis [J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 2009, 147(1): 140-147.e2.

[53] Rothova A, de Boer JH, Ten Dam-van Loon NH, et al. Usefulness of aqueous humor analysis for the diagnosis of posterior uveitis [J]. Ophthalmology, 2008, 115(2): 306-311.

[54] Errera MH, Goldschmidt P, Batellier L, et al. Real-time polymerase chain reaction and intraocular antibody production for the diagnosis of viral versus toxoplasmic infectious posterior uveitis [J]. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2011, 249(12): 1837-1846.

[55] Palani D, Kulandai LT, Naraharirao MH, et al. Application of polymerase chain reaction-based restriction fragment length polymorphism in typing ocular rapid-growing nontuberculous mycobacterial isolates from three patients with postoperative endophthalmitis [J]. Cornea, 2007, 26(6): 729-735.

[56] Cornut PL, Sobas CR, Perard L, et al. Detection of Treponema pallidum in aqueous humor by real-time polymerase chain reaction [J]. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2011, 19(2): 127-128.

[57] Hayden RT, Qian X, Roberts GD, et al. In situ hybridization for the identification of yeastlike organisms in tissue section[J]. Diagn Mol Pathol, 2001, 10(1): 15-23.

[58] Patel N, Miller D, Relhan N, et al. Peptide nucleic acid-fluorescence in situ hybridization for detection of Staphylococci from endophthalmitis isolates: a proof-ofconcept study [J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2017, 58(10): 4307-4309.

[59] Besser J, Carleton HA, Gerner-Smidt P, et al. Next-generation sequencing technologies and their application to the study and control of bacterial infections [J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2018, 24(4): 335-341.

[60] Deurenberg RH, Bathoorn E, Chlebowicz MA, et al. Application of next generation sequencing in clinical microbiology and infection prevention [J]. J Biotechnol, 2017, 243: 16-24.

[61] Li Z, Breitwieser FP, Lu J, et al. Identifying corneal infections in formalin-fixed specimens using next generation sequencing[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2018, 59(1): 280-288.

[62] Ai JW, Weng SS, Cheng Q, et al. Human endophthalmitis caused by pseudorabies virus infection, China, 2017 [J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2018, 24(6): 1087-1090.

[63] Relhan N, Forster RK, Flynn HW Jr. Endophthalmitis: then and now [J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 2018, 187: ⅩⅩ-ⅩⅩⅦ.

[64] 中華医学会眼科学分会白内障及人工晶状体学组. 我国白内障摘除手术后感染性眼内炎防治专家共识(2017年)[J]. 中华眼科杂志, 2017, 53(11): 810-813.