衰老导致卵巢功能低下研究进展

2019-09-24刘传明丁利军李佳音戴建武孙海翔

刘传明,丁利军,2,李佳音,戴建武,孙海翔

衰老导致卵巢功能低下研究进展

刘传明1,丁利军1,2,李佳音3,戴建武3,孙海翔1

1. 南京大学医学院附属鼓楼医院生殖医学中心,南京 210008 2. 南京大学医学院附属鼓楼医院临床干细胞研究中心,南京 210008 3. 中国科学院遗传与发育生物学研究所,分子发育生物学国家重点实验室,北京 100190

由于社会角色的转变,女性生育延迟现象明显。女性卵巢功能一般从35岁时开始下降,主要表现为卵泡数量减少和卵母细胞质量下降。目前临床上对于卵巢功能低下的诊断主要依据血清卵泡刺激素(follicle stimulating hormone, FSH)、血清抗苗勒氏管激素(anti-Müllerian hormone, AMH)、窦卵泡计数、年龄、月经和抑制素B等指标。目前研究发现,伴随年龄的增加,女性卵巢内细胞会出现线粒体功能失调、染色质短缩、DNA修复减少、表观遗传学改变和代谢失序。本文在简要介绍卵巢功能低下临床诊断的基础上,对衰老导致卵巢功能低下的相关因素进行了总结,并深入探讨了其发生的分子机制及潜在的干预靶点,以期为有效改善高龄女性的卵巢功能提供思路。

卵巢;衰老;线粒体;遗传;表观遗传

自20世纪70年代以来,因经济、社会等因素使得女性生育延迟成为一种普遍的社会现象[1]。根据中国人口协会、国家计生委联名发布的最新《中国不孕不育现状调研报告》显示,目前我国的不孕不育率约为12.5%,并有逐年增高的趋势。美国疾病预防控制中心2015年的数据显示,美国女性初次生育年龄由21.2岁(1970年),上升至25.8岁,35岁初产妇超过1/12;2017年韩国女性初次生育年龄平均达到31岁。研究发现与小于35岁的女性相比,高龄女性更易出现不孕、流产、死胎和多胎等危险,而衰老导致的卵巢功能低下可能在其中发挥关键作用[2~4]。因此,衰老导致卵巢功能低下研究成为生殖医学的热点之一。本文简要介绍了卵巢功能低下的诊断标准,并深入探讨了衰老影响卵巢功能的可能机制及已知的治疗方法。

1 卵巢功能低下的临床诊断

卵巢功能低下引起的卵母细胞数量和质量的下降是影响妊娠的主要因素。卵巢功能低下表现为原始卵泡池的耗竭。卵巢的主要功能在女性约50岁时基本丧失[5]。女性卵巢功能低下会增加一系列并发症的发病风险,如骨质疏松、心血管疾病、复发性抑郁症和认知功能障碍等,从而降低生活质量[6,7]。目前卵巢功能低下的主要诊断指标包括:年龄、卵泡刺激素(follicle-stimulating hormone, FSH)、抗苗勒氏管激素(anti-Müllerian hormone, AMH)、抑制素B (inhibin B, INHB)、窦卵泡数(antral follicle count, AFC)、卵巢间质血流和基础卵巢体积等[8]。尽管AMH和AFC被广泛用于卵巢功能低下的诊断,但是目前尚没有一个指标被证实可以独立预测卵巢功能[9]。在既定范围内与年龄相符的功能性卵巢储备下降称为生理性卵巢功能衰老(normal ovarian aging, NOA)。另外,研究显示人群中约10%的女性会出现与年龄不符的功能性卵巢储备降低,但没有表现出显著的临床症状,被称为隐匿性卵巢功能低下或隐匿性卵巢功能不全(occult premature ovarian inscufficiency, OPOI)[10,11]。此外,还有约1%女性会在40岁之前出现卵巢内卵泡提前耗竭,完全停经等症状,被称为早发性卵巢功能低下或早发性卵巢功能不全(premature ovarian inscufficiency, POI)。欧洲人类生殖与胚胎协会(ESHRE)规定了POI的诊断标准:大于4个月的月经稀发或者停经同时FSH检测值高于25 U/L。而对于临床表现更为严重的卵巢早衰(premature ovarian failure, POF),其诊断标准包括FSH> 40 U/L并伴有超过4个月的继发性闭经[12]。

2 衰老导致卵巢功能低下的致病因素

2.1 线粒体功能失调

线粒体与卵巢功能密切相关。衰老会导致线粒体DNA (mitochondrial DNA, mtDNA)不稳定性增加,引起卵巢细胞尤其是卵母细胞中线粒体DNA突变的积累。线粒体的生物发生对于卵泡和早期胚胎发育至关重要,而卵巢功能下降也会严重影响卵母细胞及周围颗粒细胞中线粒体的生成及线粒体功能[13]。因此,作为线粒体拷贝数量最多的细胞,卵母细胞中线粒体的功能失调加速卵巢功能低下,从而导致妊娠失败。形态学和功能学研究发现,衰老会影响细胞,特别是卵母细胞线粒体功能,导致线粒体肿胀、空泡化,小线粒体碎片含量增加[14~16]。氧化应激(reactive oxidative stress, ROS)被认为是衰老相关的获得性mtDNA突变的主要来源[17]。“线粒体自由基”理论认为衰老积聚了高水平的氧自由基和ROS,导致mtDNA突变,进而影响功能性电子传递链(electron transfer chain, ETC)的产生;而mtDNA的突变进一步加剧ROS和mtDNA突变的积累,形成恶性循环,导致ATP产生减少、细胞周期停滞甚至细胞凋亡。除ROS外,多种线粒体功能失调也被证实与卵巢细胞的衰老有关,包括线粒体融合、ETC失活、线粒体代谢改变和钙稳态失衡等[18]。采用多组学分析衰老过程中mtDNA变化时发现,线粒体单一基因位点的改变即可影响线粒体蛋白稳态、加速活性氧生成、导致端粒缩短[19]。作为一种重要的参与线粒体融合的线粒体膜蛋白,线粒体融合蛋白2 (mitofusin 2, Mfn2)敲除小鼠出现严重的发育延迟,并且因胎盘缺陷导致胚胎死亡,卵母细胞内特异性敲除该基因后雌性小鼠不孕[20]。而参与介导线粒体分裂的动力相关蛋白(dynamin-related protein 1, DRP1)也对维持生殖细胞的正常功能至关重要,在卵母细胞内特异性敲除DRP1后,小鼠卵泡成熟和排卵均出现障碍[21]。此外,控制线粒体质量的相关蛋白酶在卵巢细胞中发挥重要作用,包括CLPP、AFG3L2、PHB、OMA1、LONP1和PARL等在内的蛋白酶,其缺陷会导致相关线粒体疾病的出现,并加速卵母细胞的衰老[22~24]。

2.2 遗传学改变

卵巢功能下降与卵母细胞质量下降密切相关。女性卵巢从出生开始在整个生育周期中不断受到激素、代谢、免疫等因素的影响,从而导致卵巢内卵母细胞和体细胞出现DNA损伤。研究表明,随着年龄增长,卵母细胞核DNA双链断裂(double strand break, DSB)明显增多[25],并且卵巢中DNA修复基因的表达减少,使得DSB不断累积。而衰老导致的减数分裂过程中染色体粘结蛋白的缺失会影响卵母细胞染色体分离,导致非整倍体卵母细胞比例增加,进而影响卵母细胞功能[26]。此外,在姐妹染色单体分离过程中,着丝粒同时受到来自相反方向的纺锤丝的牵引,引起染色体的错误分离,这可能是卵母细胞非整倍体的另一重要原因[27]。纺锤体组装检查点(spindle assembly checkpoint, SAC)可以阻止染色体分离,直到姐妹染色单体正确地连接于有丝分裂纺锤体上,其缺失也会导致非整倍体率显著提高[28,29]。对CD1小鼠研究表明,12月龄的高龄组小鼠卵母细胞非整倍体发生率为31.6%,而年轻组仅为4.9%[30]。老化的卵母细胞普遍存在端粒的缩短,而缩短的端粒会引发DNA损伤反应[31]。端粒的缩短主要是由于衰老引起的ROS水平增高所导致的[32]。颗粒细胞质量下降与卵母细胞质量亦密切相关,随着年龄增长,颗粒细胞中同样存在DNA损伤增多,端粒缩短等情况[33,34]。

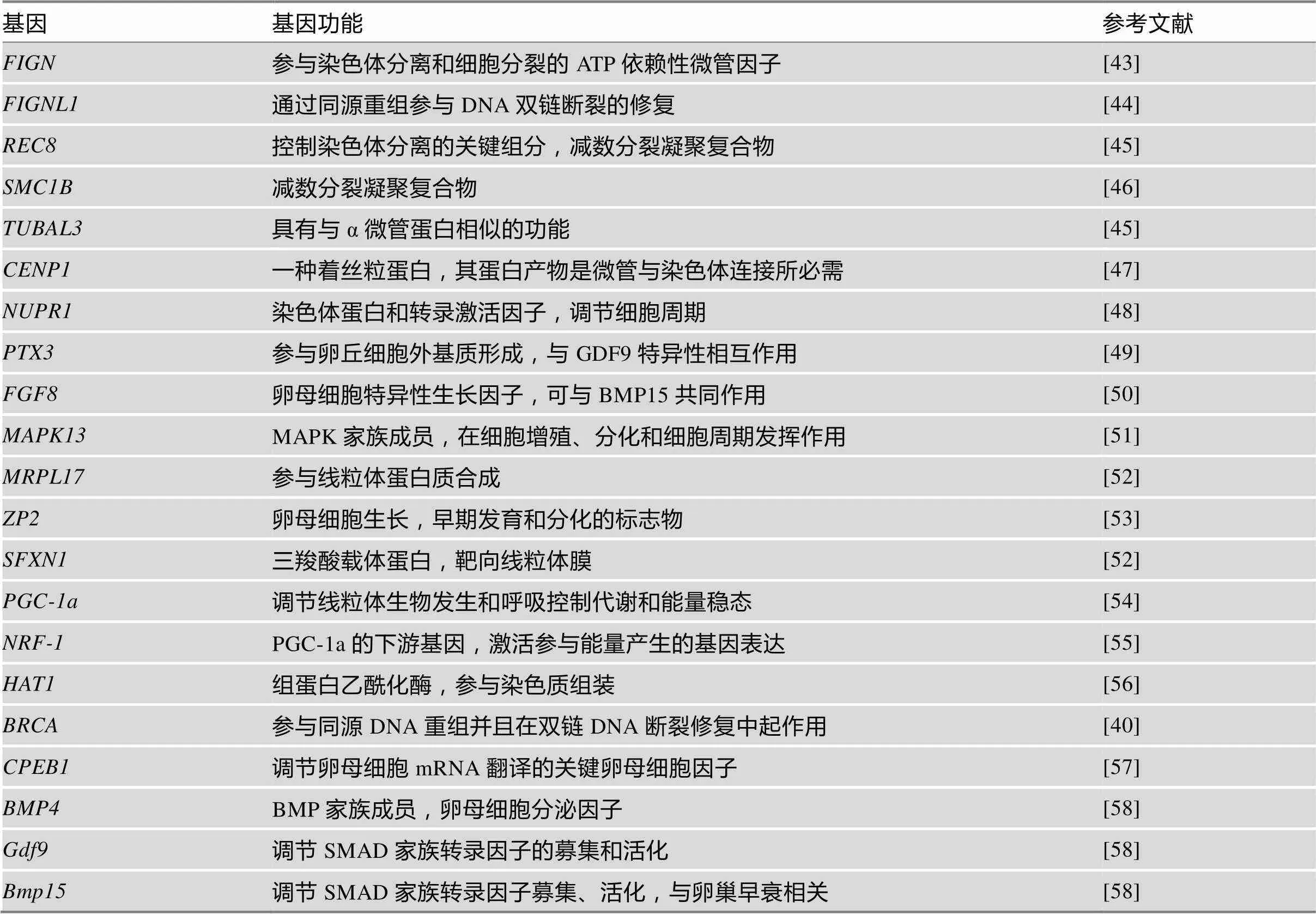

多组学研究发现,衰老可导致卵母细胞内参与细胞周期信号转导的基因发生显著变化,同时与SAC、DNA稳定性、染色体分离、细胞分裂、微管和RNA定位等相关的蛋白质表达也发生变化[35,36]。通过对高龄和年轻大鼠原始卵泡进行微阵列分析,发现与核苷酸结合、RNA结合、核糖体结构成分、转录因子活性、细胞周期、同源重组、减数分裂、DNA复制和MAPK信号通路相关的分子在转录水平差异显著[37]。其他物种包括日本黑牛()、C57BL/6小鼠和海门山羊)的研究得到类似的变化趋势,特别是在高龄母牛卵母细胞中发现真核起始因子2 (eukaryotic initiation factor 2, EIf2)信号通路的相关分子高表达[37~39]。已经证实很多基因的改变会影响卵母细胞质量,加速卵巢衰老。如参与减数分裂纺锤体组装的乳腺癌基因1(breast cancer 1,),其突变会导致女性卵巢功能加速下降[40,41]。伴随雌性小鼠年龄的增加,卵母细胞中染色体结构维持蛋白5/6 (structural maintenance of chromosomes 5/6, SMC5/6)表达水平下降;其年龄依赖性消耗导致卵母细胞非整倍体发生率显著增加[42]。已知伴随年龄增加,卵母细胞内发生显著性变化的基因如表1所示。

2.3 表观遗传学改变

在卵母细胞发生和早期胚胎发育过程中,建立适当的表观遗传修饰是个体发生的一个重要事件。目前研究已经证实,在衰老的过程中生殖细胞的DNA会发生不正确的表观遗传学修饰,如异常DNA甲基化、组蛋白乙酰化和组蛋白甲基化等。这些异常表观遗传修饰可能会加速衰老[59]。目前认为,卵母细胞中DNA甲基化和组蛋白修饰在生殖发育过程中发挥重要作用。Hamatani等[60]比较年轻和高龄C57BL/6雌性小鼠MII期卵母细胞的mRNA表达谱时发现:5%的转录本存在明显差异,其中包括编码参与表观遗传修饰、涉及染色质重塑和DNA甲基化的蛋白质,如DNA甲基转移酶1、3a、3b、3L和DNMT相关蛋白-1 (DNA methyltransferase 1-associated protein 1, DAMP1)等。采用其他品系小鼠进行微阵列基因表达分析,获得类似的转录本变化[61]。衰老能够促进卵母细胞DNA甲基转移酶的高表达,从而催化DNA甲基化。对老龄昆明小鼠的研究发现,其胚胎致死率和胎儿畸形率均高于年轻组,这与卵母细胞DNA的甲基化异常密切相关[62]。而组蛋白乙酰化调控染色体浓缩、DNA断裂修复和转录等细胞功能[63~65]。在哺乳动物卵母细胞成熟期间,组蛋白H3和H4发生乙酰化修饰。研究发现,与年轻卵母细胞相比,高龄动物卵母细胞的基因表达和组蛋白乙酰化修饰均发生显著改变[66]。组蛋白3赖氨酸4 (H3K4)的甲基化通常与基因激活和衰老相关[67,68]。H3K4的二甲基化在年轻动物的MII期卵母细胞中表达水平更高。而当H3K4三甲基化去甲基化酶–视黄醇结合蛋白2 (retinol binding protein 2, RBP2)缺乏时,蠕虫和果蝇的寿命出现缩短[69]。此外,在高龄动物的GV期卵母细胞中,组蛋白甲基化相关因子(CBX1和SIRT1)的表达变化趋势相反,CBX1的表达显著升高,而SIRT1的表达则是降低的[70]。

表1 衰老引起卵母细胞质量降低的基因

2.4 代谢失序

女性随着年龄的增加会出现卵巢功能低下,低雌激素血症,以及一系列的代谢紊乱症状。处于绝经过渡期的女性会增加出现代谢综合征的风险。研究发现高龄女性的卵泡液内脂质成分发生明显改变,其鞘磷脂、甘油二酯和甘油三酯的丰度更高,而鞘磷脂代谢是凋亡过程中的重要事件,甘油三酯也与卵泡成熟和卵母细胞质量下降相关[71,72]。同时,高龄女性的卵泡液中谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶和超氧化物歧化酶含量较低[73,74]。研究表明,晚期糖基化产物增多(advanced glycation end products, AGEs)与卵巢功能下降密切相关,卵泡内AGEs产物积累会直接损伤蛋白质,诱导一系列的氧化应激反应,并增加炎症反应,引发早期卵巢功能下降[75,76]。外界环境可以通过调节关键的代谢感知蛋白(如SIRT1和AMPK)来影响衰老,这些蛋白与mTOR和胰岛素/胰岛素生长因子1相互作用控制能量代谢和细胞生长。衰老可以通过这种方式降低NAD+/NADH和AMP/ATP比例,损伤线粒体功能,增加氧化应激[77~79]。对不同年龄的C57BL/6小鼠的卵母细胞进行单细胞转录本测序时发现:衰老小鼠卵母细胞的蛋白质代谢发生变化,与蛋白质质量控制(蛋白质修饰和非折叠蛋白反应)相关的基因表达出现显著变化,与蛋白质代谢相关的细胞成分(核仁)出现中断,同时代谢相关蛋白酶的表达存在差异,而炎症相关因子表达、细胞质中核糖体数量均显著增加[80]。近期研究发现,在衰老小鼠的卵母细胞内核糖体蛋白S2 (ribosomal protein S2, RPS2)表达增加,进一步表明衰老会导致核糖体数量的增加[81]。而伴随着卵巢功能的下降,包括成熟促进因子(maturation promoting factor, MPF)、sirtuin家族(SIRT1/2/3)、抗凋亡蛋白B细胞淋巴瘤-2家族蛋白(B-cell lymphoma-2, BCL-2)和半胱天冬酶(caspase)等蛋白的表达或修饰发生显著变化[82~84]。

3 卵巢功能低下的干预措施

3.1 药物干预

由于线粒体功能障碍与卵巢功能低下有关,因此线粒体功能的改善可能会减缓或逆转卵巢功能低下。包括辅酶Q10、白藜芦醇、雷帕霉素、α硫辛酸和SIRT3等在内的线粒体营养药物被用于改善卵巢功能[85]。此外,有研究表明,ω-3脂肪酸能够延迟卵巢功能下降,提高卵母细胞质量[86]。而一些具有减少氧化应激、抗炎和清除自由基效用的药物,如C-藻蓝蛋白(C-Phycocyanin, C-PC)、褪黑素等似乎也可以改善卵母细胞的质量,提高女性生育力[86,87]。临床上对于卵巢功能低下的患者,拮抗剂方案相较于长方案有类似的获卵数,而GnRH-a短方案虽然有更多的获卵数,但是临床妊娠结局与其他方案并无差异[5]。文献报道,促排卵周期前8周开始口服脱氢表雄酮(dehydroepiandrosterone, DHEA)可以改善卵巢功能低下患者的临床结局[88]。在拮抗剂方案-胞浆内单精子注射(intracytoplasmic sperm injection,ICSI)周期中补充生长激素可以显著增加卵巢反应不良患者的获卵数、受精卵数和可移植胚胎数,但是妊娠率和活产率并没有改善[89]。衰老导致的卵巢功能低下原因多样,机制复杂,虽然很多药物被证实能够缓解卵巢功能的减退,但到目前为止,尚无有效药物可以完全延迟卵巢功能的下降。

3.2 线粒体移植

线粒体在卵母细胞中发挥着重要作用,并且是植入前胚胎发育过程中ATP的主要来源。卵母细胞线粒体功能障碍被认为是高龄女性卵母细胞发育潜能差的关键因素。包括药物治疗、细胞质移植、细胞核移植及线粒体移植在内的多种方法被用来增强衰老卵母细胞中线粒体的完整性、活性和数量[90]。研究表明卵母细胞胞质移植可以明显改善胚胎发育情况,促进妊娠并获得健康胎儿[90]。然而该技术移植成分复杂,线粒体基因存在异质性,会造成“三个遗传亲本”的伦理问题,已于2002年被美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)暂停[91]。而异体线粒体移植,即从携带异常线粒体的患者的未受精卵母细胞中取出核DNA,然后转移到含有健康线粒体的去核供体卵母细胞内,此种方法临床效果不佳,并且存在两种mtDNA基因组的伦理争议[92]。文献报道称自体线粒体移植可以显著改善卵母细胞质量,提高高龄女性的妊娠成功率[93],但是亦有研究指出自体线粒体移植并不能改善卵母细胞质量[94]。因此,线粒体移植的安全性和有效性需要进一步证实。

3.3 卵巢内干细胞移植

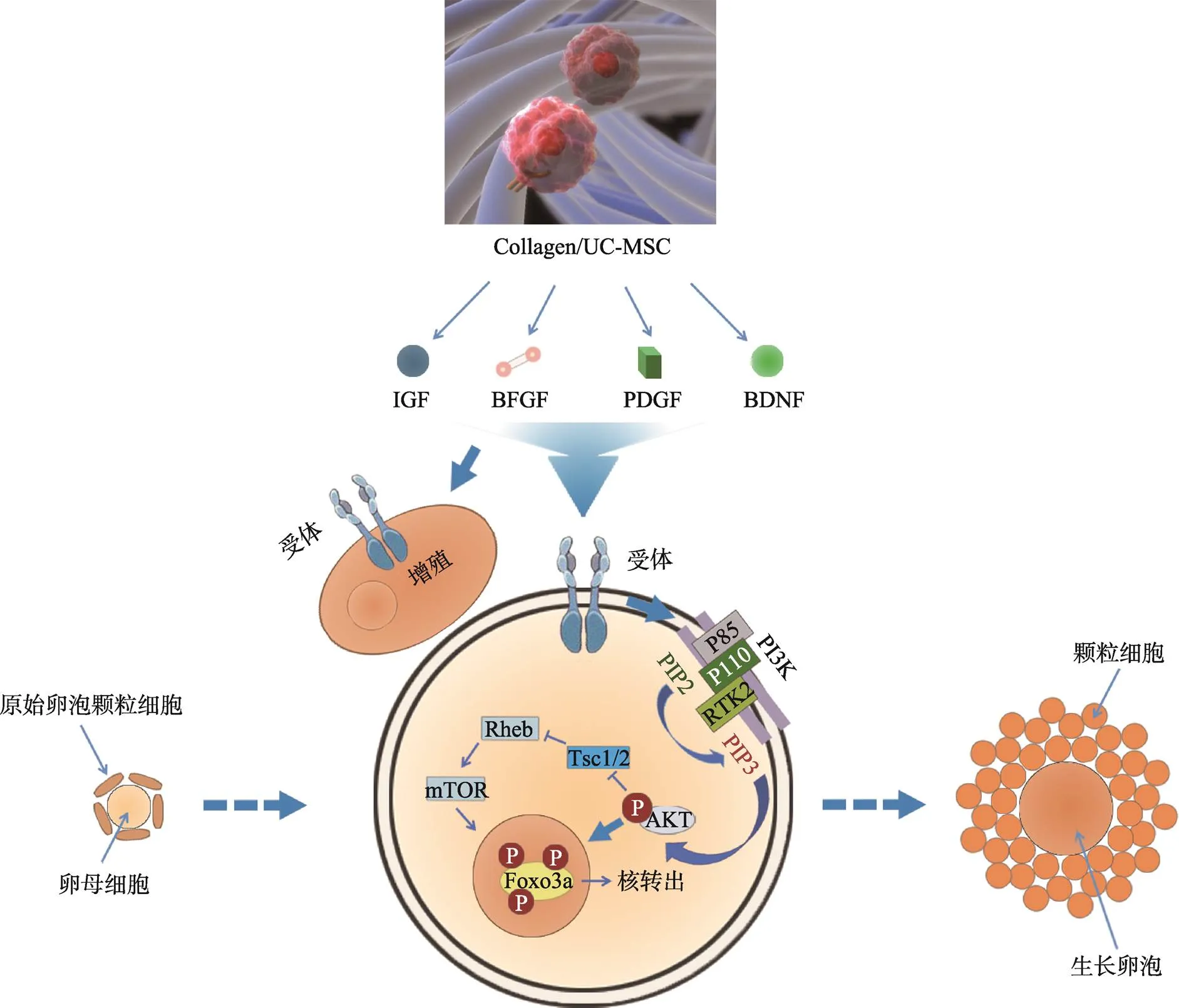

已经证实,卵巢内间充质干细胞(mesenchymal stem cell, MSCs)移植可以恢复卵巢功能,并提高啮齿动物的生育力[95,96]。而胶原蛋白支架能够支持细胞的附着、增殖和分化,研究表明胶原蛋白支架可以将间充质干细胞锚定于支架网络中,从而增加MSCs的卵巢滞留时间[97,98]。我们前期研究表明,脂肪组织来源的MSCs联合胶原支架移植可以促进颗粒细胞增殖,改善卵巢早衰大鼠的卵泡发育和生育力[98]。但是MSCs改善卵巢功能的具体机制尚不清楚。原始生殖细胞(primordial germ cell, PGCs)和卵巢干细胞(ovarian stem cell, OSCs)是重要的卵母细胞前体细胞[99]。在小鼠中,移植的OSCs所形成的卵母细胞可以完全成熟并且能够形成胚胎和后代[100]。在我们最近的一项研究中发现,通过采用卵巢、胶原/脐带间充质干细胞共培养的方法,可以促进小鼠卵巢内FOXO3a和FOXO1的磷酸化,进而促进原始卵泡的激活,其机制如图1所示[9,101,102]。共培养后的卵巢移植到受体小鼠肾被囊内,在给予FSH和HCG刺激后,原始卵泡可发育到排卵前卵泡阶段[101]。在通过国家卫计委干细胞临床研究备案和医院伦理委员会批准后,本课题组进行了POF合并不孕症患者脐带间充质干细胞移植干预的临床研究,移植后3个月,相较于对照组,实验组FSH水平明显降低,雌激素水平、卵巢体积和卵巢血流明显增加[101]。项目实施至今,在前期入组的23人中,随访发现9人有优势卵泡活动,已有2位患者获得临床妊娠,另有2位患者已获得可移植胚胎。首例健康婴儿于2018年1月12日在南京鼓楼医院顺利诞生。这些研究表明,干细胞可以有效提高POF患者的妊娠成功率,具有良好的临床应用前景,但是仍需进一步的大样本、多中心的干细胞临床研究加以验证。

图1 胶原/脐带间充质干细胞促进颗粒细胞增殖和卵母细胞激活的分子机制

脐带间充质干细胞在三维支架中分泌多种生长因子,包括IGF/bFGF/PDGF/BDNF等,这些因子可以与颗粒细胞和卵母细胞表面受体结合,一方面促进颗粒细胞增殖;另一方面激活卵母细胞内PI3K/AKT通路,使得PIP2磷酸化成为PIP3聚集在卵母细胞膜上,进而导致AKT的活化,通过mTOR增加FOXO3a出核,从而激活卵母细胞,使得原始卵泡发育至生长卵泡阶段。

4 结语与展望

卵巢功能低下是影响妊娠的重要因素。衰老会影响卵巢内多种细胞的质量和功能,导致线粒体功能障碍、非整倍体性、代谢紊乱和表观遗传修饰改变等。包括改善线粒体功能、减少氧化应激、清除自由基的药物对于卵巢功能低下的治疗作用较小,临床干预效果并不显著。线粒体移植的效果存在争议,并且伦理上有待商榷。而前期实验表明间充质类干细胞能够改善卵巢功能低下患者的卵巢功能,提高妊娠率,具备良好的临床应用前景,但是仍需扩大临床研究,证实干细胞对卵巢功能低下患者的有效性和安全性。随着生育延迟及二胎政策的放开,衰老所导致的卵巢功能低下正在影响越来越多育龄妇女的生育需求。目前仍有两个主要问题尚未解决,一是衰老引起卵母细胞质量下降的具体机制,二是寻求切实有效的治疗方法改善高龄引起的卵巢功能衰退。伴随高通量技术(包括表观遗传组学、转录组学、蛋白组学和代谢组学等)的迅速发展,尤其是检测单个细胞中各组学变化相关技术的成熟,将加速我们对衰老相关的卵巢功能低下的认识。卵巢功能低下的机制复杂,临床干预困难,如何改善生理性和早发性卵巢功能低下患者的卵巢功能、明确衰老影响卵巢内细胞功能的机制仍任重道远。

[1] Wang T, Gao YY, Chen L, Nie ZW, Cheng W, Liu X, Schatten H, Zhang X, Miao YL. Melatonin prevents postovulatory oocyte aging and promotes subsequent embryonic development in the pig., 2017, 9(6): 1552–1564.

[2] Yuan Y, Hakimi P, Kao C, Kao A, Liu R, Janocha A, Boyd-Tressler A, Hang X, Alhoraibi H, Slater E, Xia K, Cao P, Shue Q, Ching TT, Hsu AL, Erzurum SC, Dubyak GR, Berger NA, Hanson RW, Feng Z. Reciprocal changes in phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and pyruvate kinase with age are a determinant of aging in caenorhabditis elegans., 2016, 291(3): 1307–1319.

[3] Schandera J, Mackey TK. Mitochondrial replacement techniques: divergence in global policy., 2016, 32(7): 385–390.

[4] Li Q, Geng X, Zheng W, Tang J, Xu B, Shi Q. Current understanding of ovarian aging., 2012, 55(8): 659–669.

[5] Ata B, Seli E. Strategies for controlled ovarian stimulation in the setting of ovarian aging., 2015, 33(6): 436–448.

[6] Tachibana M, Kuno T, Yaegashi N. Mitochondrial replacement therapy and assisted reproductive technology: a paradigm shift toward treatment of genetic diseases in gametes or in early embryos., 2018, 17(4): 421–433.

[7] Kristensen SG, Pors SE, Andersen CY. Improving oocyte quality by transfer of autologous mitochondria from fully grown oocytes., 2017, 32(4): 725–732.

[8] Hansen KR, Craig LB, Zavy MT, Klein NA, Soules MR. Ovarian primordial and nongrowing follicle counts according to the stages of reproductive aging workshop (STRAW) staging system.,2012, 19(2): 164–171.

[9] Nelson SM, Telfer EE, Anderson RA. The ageing ovary and uterus: new biological insights., 2013, 19(1): 67–83.

[10] Iliodromiti S, Iglesias Sanchez C, Messow CM, Cruz M, Garcia Velasco J, Nelson SM. Excessive age-related decline in functional ovarian reserve in infertile women: prospective cohort of 15,500 women., 2016, 101(9): 3548–3554.

[11] Gleicher N, Weghofer A, Barad DH. Defining ovarian reserve to better understand ovarian aging., 2011, 9: 23.

[12] Sills ES, Alper MM, Walsh AP. Ovarian reserve screening in infertility: practical applications and theoretical directions for research., 2009, 146(1): 30–36.

[13] May-Panloup P, Boucret L, Chao de la Barca JM, Desquiret-Dumas V, Ferré-L'Hotellier V, Morinière Descamps P, Procaccio V, Reynier P. Ovarian ageing: the role of mitochondria in oocytes and follicles., 2016, 22(6): 725–743.

[14] Wilding M, Dale B, Marino M, di Matteo L, Alviggi C, Pisaturo ML, Lombardi L, De Placido G. Mitochondrial aggregation patterns and activity in human oocytes and preimplantation embryos.,2001, 16(5): 909–917.

[15] Ben-Meir A, Burstein E, Borrego-Alvarez A, Chong J, Wong E, Yavorska T, Naranian T, Chi M, Wang Y, Bentov Y, Alexis J, Meriano J, Sung HK, Gasser DL, Moley KH, Hekimi S, Casper RF, Jurisicova A. Coenzyme Q10 restores oocyte mitochondrial function and fertility during reproductive aging., 2015, 14(5): 887–895.

[16] Pan YF, Wang YY, Chen JW, FAN YM. Mitochondrial metabolism’s effect on epigenetic change and aging., 2019, doi: 10.16288/j.yczz.19-065.潘云枫, 王演怡, 陈静雯, 范怡梅. 线粒体代谢介导的表观遗传改变与衰老研究. 遗传, 2019, doi: 10.16288/j.yczz.19-065.

[17] Babayev E, Wang T, Szigeti-Buck K, Lowther K, Taylor HS, Horvath T, Seli E. Reproductive aging is associated with changes in oocyte mitochondrial dynamics, function, and mtDNA quantity., 2016, 93: 121–130.

[18] Wang T, Zhang M, Jiang Z, Seli E. Mitochondrial dysfunction and ovarian aging., 2017,77:e12651.

[19] Latorre-Pellicer A, Moreno-Loshuertos R, Lechuga- Vieco AV, Sánchez-Cabo F, Torroja C, Acín-Pérez R, Calvo E, Aix E, González-Guerra A, Logan A, Bernad- Miana ML, Romanos E, Cruz R, Cogliati S, Sobrino B, Carracedo Á, Pérez-Martos A, Fernández-Silva P, Ruíz-Cabello J, Murphy MP, Flores I, Vázquez J, Enríquez JA. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA matching shapes metabolism and healthy ageing.,2016, 535(7613): 561–565.

[20] Zhang M, Bener MB, Jiang Z, Wang T, Esencan E, Scott R, Horvath T, Seli E. Mitofusin 2 plays a role in oocyte and follicle development, and is required to maintain ovarian follicular reserve during reproductive aging., 2019, 11(12): 3919–3938.

[21] Udagawa O, Ishihara T, Maeda M, Matsunaga Y, Tsukamoto S, Kawano N, Miyado K,Shitara H, Yokota S, Nomura M, Mihara K, Mizushima N, Ishihara N. Mitochondrial fission factor Drp1 maintains oocyte quality via dynamic rearrangement of multiple organelles., 2014, 24(20): 2451–2458.

[22] Maltecca F, Aghaie A, Schroeder DG, Cassina L, Taylor BA, Phillips SJ, Malaguti M, Previtali S, Guénet JL, Quattrini A, Cox GA, Casari G. The mitochondrial protease AFG3L2 is essential for axonal development., 2008, 28(11): 2827–2836.

[23] Gispert S, Parganlija D, Klinkenberg M, Dröse S, Wittig I, Mittelbronn M, Grzmil P, Koob S, Hamann A, Walter M, Büchel F, Adler T, Hrabé de Angelis M, Busch DH, Zell A, Reichert AS, Brandt U, Osiewacz HD, Jendrach M, Auburger G. Loss of mitochondrial peptidase Clpp leads to infertility, hearing loss plus growth retardation via accumulation of CLPX, mtDNA and inflammatory factors., 2013, 2(24): 4871–4887.

[24] Ferreirinha F, Quattrini A, Pirozzi M, Valsecchi V, Dina G, Broccoli V, Auricchio A, Piemonte F, Tozzi G, Gaeta L, Casari G, Ballabio A, Rugarli EI. Axonal degeneration in paraplegin-deficient mice is associated with abnormal mitochondria and impairment of axonal transport., 2004, 113(2): 231–242.

[25] Solovjeva L, Firsanov D, Vasilishina A, Chagin V, Pleskach N, Kropotov A, Svetlova M. DNA double- strand break repair is impaired in presenescent Syrian hamster fibroblasts., 2015, 16: 18.

[26] Hassold T, Hunt P. To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy., 2001, 2(4): 280–291.

[27] Shomper M, Lappa C, FitzHarris G. Kinetochore microtubule establishment is defective in oocytes from aged mice., 2014, 13(7): 1171–1179.

[28] Yun Y, Holt JE, Lane SI, McLaughlin EA, Merriman JA, Jones KT. Reduced ability to recover from spindle disruption and loss of kinetochore spindle assembly checkpoint proteins in oocytes from aged mice.,2014, 13(12): 1938–1947.

[29] Polanski Z. Spindle assembly checkpoint regulation of chromosome segregation in mammalian oocytes., 2013, 25(3): 472–483.

[30] Cheng JM, Li J, Tang JX, Chen SR, Deng SL, Jin C, Zhang Y, Wang XX, Zhou CX, Liu YX. Elevated intracellular pH appears in aged oocytes and causes oocyte aneuploidy associated with the loss of cohesion in mice., 2016, 15(18): 2454–2463.

[31] Wang H, Jo YJ, Oh JS, Kim NH. Quercetin delays postovulatory aging of mouse oocytes by regulating SIRT expression and MPF activity., 2017, 8(24): 38631–38641.

[32] Keefe DL. Telomeres, reproductive aging, and genomic instability during early development., 2016, 23(12): 1612–1615.

[33] Tatone C, Amicarelli F. The aging ovary the poor granulosa cells., 2013, 99(1): 12–17.

[34] Iwata H. Age-associated changes in granulosa cells and follicular fluid in cows., 2017, 63(4): 339–345.

[35] Grøndahl ML, Yding Andersen C, Bogstad J, Nielsen FC, Meinertz H, Borup R. Gene expression profiles of single human mature oocytes in relation to age., 2010, 25(4): 957–968.

[36] Duncan FE, Jasti S, Paulson A, Kelsh JM, Fegley B, Gerton JL. Age-associated dysregulation of protein metabolism in the mammalian oocyte., 2017, 16(6): 1381–1393.

[37] Govindaraj V, Krishnagiri H, Chakraborty P, Vasudevan M, Rao AJ. Age-related changes in gene expression patterns of immature and aged rat primordial follicles., 2017, 63(1): 37–48.

[38] Dorji, Ohkubo Y, Miyoshi K, Yoshida M. Gene expression profile differences in embryos derived from prepubertal and adult Japanese Black cattle during in vitro development., 2012, 24(2): 370–381.

[39] Takeo S, Kawahara-Miki R, Goto H, Cao F, Kimura K, Monji Y, Kuwayama T, Iwata H. Age-associated changes in gene expression and developmental competence of bovine oocytes, and a possible countermeasure against age-associated events., 2013, 80(7): 508–521.

[40] Oktay K, Turan V, Titus S, Stobezki R, Liu L. BRCA mutations, DNA repair deficiency, and ovarian aging., 2015, 93(3): 67.

[41] Lin W, Titus S, Moy F, Ginsburg ES, Oktay K. Ovarian aging in women with BRCA germline mutations., 2017, 102(10): 3839–3847.

[42] Kobayashi H, Sakurai T, Imai M, Takahashi N, Fukuda A, Yayoi O, Sato S, Nakabayashi K, Hata K, Sotomaru Y, Suzuki Y, Kono T. Contribution of intragenic DNA methylation in mouse gametic DNA methylomes to establish oocyte-specific heritable marks., 2012, 8(1): e1002440.

[43] Mukherjee S, Diaz Valencia JD, Stewman S, Metz J, Monnier S, Rath U, Asenjo AB, Charafeddine RA, Sosa HJ, Ross JL, Ma A, Sharp DJ. Human Fidgetin is a microtubule severing the enzyme and minus-end depolymerase that regulates mitosis., 2012, 11(12): 2359–2366.

[44] Govindaraj V, Rao AJ. Comparative proteomic analysis of primordial follicles from ovaries of immature and aged rats., 2015, 61(6): 367–375.

[45] Tachibana-Konwalski K, Godwin J, van der Weyden L, Champion L, Kudo NR, Adams DJ, Nasmyth K. Rec8-containing cohesin maintains bivalents without turnover during the growing phase of mouse oocytes., 2010, 24(22): 2505–2516.

[46] Tsutsumi M, Fujiwara R, Nishizawa H, Ito M, Kogo H, Inagaki H, Ohye T, Kato T, Fujii T, Kurahashi H. Age-related decrease of meiotic cohesins in human oocytes., 2014, 9(5): e96710.

[47] Fortuño C, Labarta E. Genetics of primary ovarian insufficiency: a review., 2014, 31(12): 1573–85.

[48] Million Passe CM, White CR, King MW, Quirk PL, Iovanna JL, Quirk CC. Loss of the protein NUPR1 (p8) leads to delayed LHB expression, delayed ovarian maturation, and testicular development of a sertoli-cell- only syndrome-like phenotype in mice., 2008, 79(4): 598–607.

[49] Salustri A, Garlanda C, Hirsch E, De Acetis M, Maccagno A, Bottazzi B, Doni A, Bastone A, Mantovani G, Beck Peccoz P, Salvatori G, Mahoney DJ, Day AJ, Siracusa G, Romani L, Mantovani A. PTX3 plays a key role in the organization of the cumulus oophorus extracellular matrix and infertilization., 2004, 131(7): 1577–1586.

[50] Sánchez F, Adriaenssens T, Romero S, Smitz J. Quantification of oocyte-specific transcripts in follicle- enclosed oocytes during antral development and maturation., 2009, 15(9): 539–550.

[51] Inoue M, Naito K, Nakayama T, Sato E. Mitogen- activated protein kinase translocates into the germinal vesicle and induces germinal vesicle breakdown in porcine oocytes., 1998, 58(1): 130–136.

[52] Li X, Han D, Kin Ting Kam R, Guo X, Chen M, Yang Y, Zhao H, Chen Y. Developmental expression of sideroflexin family genes in Xenopus embryos., 2010, 239(10): 2742–2747.

[53] Wassarman PM, Jovine L, Litscher ES. Mouse zona pellucida genes and glycoproteins., 2004, 105(2–4): 228–234.

[54] Bahrami SA, Bakhtiari N. Ursolic acid regulates aging process through enhancing of metabolic sensor proteins level., 2016, 82: 8–14.

[55] Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1., 1999, 98(1): 115–124.

[56] Cui MS, Wang XL, Tang DW, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zeng SM. Acetylation of H4K12 in porcine oocytes during in vitro aging: potential role of ooplasmic reactive oxygen species., 2011, 75(4): 638–646.

[57] Qian Y, Tu J, Tang NL, Kong GW, Chung JP, Chan WY, Lee TL. Dynamic changes of DNA epigenetic marks in mouse oocytes during natural and accelerated aging., 2015, 67: 121–127.

[58] Knight PG, Glister C. TGF-beta superfamily members and ovarian follicle development., 2006, 132(2): 191–206.

[59] Poulsen P, Esteller M, Vaag A, Fraga MF. The epigenetic basis of twin discordance in age-related diseases., 2007, 61(5 Pt 2): 38R–42R.

[60] Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Metabolic pathways in immune cell activation and quiescence.,2013, 38(4): 633–643.

[61] Govindaraj V, Krishnagiri H, Chakraborty P, Vasudevan M, Rao AJ. Age-related changes in gene expression patterns of immature and aged rat primordial follicles., 2017, 63(1): 37–48.

[62] Yue MX, Fu XW, Zhou GB, Hou YP, DU M, Wang L, Zhu SE. Abnormal DNA methylation in oocytes could be associated with a decrease in reproductive potential in old mice., 2012, 29(7): 643–650.

[63] Berger SL. Histone modifications in transcriptional regulation., 2002, 12(2): 142–148.

[64] Masumoto H, Hawke D, Kobayashi R, Verreault A. A role for cell-cycle-regulated histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation in the DNA damage response, 2005, 436(7048): 294–298.

[65] Santos-Rosa H, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Sherriff J, Bernstein BE, Emre NC, Schreiber SL, Mellor J, Kouzarides T. Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3., 2002, 419(6905): 407–411.

[66] De La Fuente R. Chromatin modifications in the germinal vesicle (GV) of mammalian oocytes., 2006, 292(1): 1–12.

[67] Manosalva I, González A. Aging changes the chromatin configuration and histone methylation of mouse oocytes at germinal vesicle stage., 2010, 74(9): 1539–1547.

[68] Eissenberg JC, Shilatifard A. Histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation in development and differentiation., 2010, 339(2): 240–249.

[69] Greer EL, Maures TJ, Hauswirth AG, Green EM, Leeman DS, Maro GS, Han S, Banko MR, Gozani O, Brunet A. Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in., 2010, 466(7304): 383–387.

[70] Manosalva I, González A. Aging changes the chromatin configuration and histone methylation of mouse oocytes at germinal vesicle stage., 2010, 74(9): 1539–1547.

[71] Cordeiro FB, Montani DA, Pilau EJ, Gozzo FC, Fraietta R, Turco EGL. Ovarian environment aging: follicular fluid lipidomic and related metabolic pathways., 2018, 35(8): 1385–1393.

[72] Yang X, Wu LL, Chura LR, Liang X, Lane M, Norman RJ, Robker RL. Exposure to lipid-rich follicular fluid is associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress and impaired oocyte maturation in cumulus-oocyte complexes., 2012, 97(6): 1438–1443.

[73] Revelli A, Delle Piane L, Casano S, Molinari E, Massobrio M, Rinaudo P. Follicular fluid content and oocyte quality: from single biochemical markers to metabolomics., 2009, 7: 40.

[74] Carbone MC, Tatone C, Delle Monache S, Marci R, Caserta D, Colonna R, Amicarelli F. Antioxidant enzymatic defences in human follicular fluid: characterization and age-dependent changes., 2003, 9(11): 639–643.

[75] Takeo S, Kimura K, Shirasuna K, Kuwayama T, Iwata H. Age-associated deterioration in follicular fluid induces a decline in bovine oocyte quality., 2017, 29(4): 759–767.

[76] Pertynska-Marczewska M, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Aging ovary and the role for advanced glycation end products., 2017, 24(3): 345–351.

[77] Feige JN, Lagouge M, Canto C, Strehle A, Houten SM, Milne JC, Lambert PD, Mataki C, Elliott PJ, Auwerx J. Specific SIRT1 activation mimics low energy levels and protects against diet-induced metabolic disorders by enhancing fat oxidation., 2008, 8(5): 347– 358.

[78] Jasper H, Jones DL. Metabolic regulation of stem cell behavior and implications for aging., 2010, 12(6): 561–565.

[79] Tilly JL, Sinclair DA. Germline energetics, aging, and female infertility., 2013, 17(6): 838–850.

[80] Branco MR, Ficz G, Reik W. Uncovering the role of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the epigenome., 2011, 13(1): 7–13.

[81] Pan H, Ma P, Zhu W, Schultz RM. Age-associated increase in aneuploidy and changes in gene expression in mouse eggs.,2008, 316(2): 397–407.

[82] Jiang GJ, Wang K, Miao DQ, Guo L, Hou Y, Schatten H, Sun QY. Protein profile changes during porcine oocyte aging and effects of caffeine on protein expression patterns., 2011, 6(12): e28996.

[83] Stricker SA, Beckstrom B, Mendoza C, Stanislawski E, Wodajo T. Oocyte aging in a marine protostome worm: the roles of maturation-promoting factor and extracellularsignal regulated kinase form of mitogen-activated protein kinase., 2016, 58(3): 250–259.

[84] Stricker SA, Ravichandran N. The potential roles of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) during the maturation and aging of oocytes produced by a marine protostome worm., 2017, 25(6): 686–696.

[85] Liu MJ, Sun AG, Zhao SG, Liu H, Ma SY, Li M, Huai YX, Zhao H, Liu HB. Resveratrol improves in vitro maturation of oocytes in aged mice and humans., 2018, 109(5): 900–907.

[86] Nehra D, Le HD, Fallon EM, Carlson SJ, Woods D, White YA, Pan AH, Guo L, Rodig SJ, Tilly JL, Rueda BR, Puder M. Prolonging the female reproductive lifespan and improving egg quality with dietary omega-3 fatty acids., 2012, 11(6): 1046–1054.

[87] Song C, Peng W, Yin S, Zhao J, Fu B, Zhang J, Mao T, Wu H, Zhang Y. Melatonin improves age-induced fertility decline and attenuates ovarian mitochondrial oxidative stress in mice., 2016, 6: 35165.

[88] Tartagni M, Cicinelli MV, Baldini D, Tartagni MV, Alrasheed H, DeSalvia MA, Loverro G, Montagnani M. Dehydroepiandrosterone decreases the age-related decline of thefertilization outcome in women younger than 40 years old., 2015, 13: 18.

[89] Bassiouny YA, Dakhly DMR, Bayoumi YA, Hashish NM. Does the addition of growth hormone to the in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection antagonist protocol improve outcomes in poor responders? A randomized, controlled trial., 2016, 105(3): 697–702.

[90] Cohen J, Scott R, Alikani M, Schimmel T, Munné S, Levron J, Wu L, Brenner C, Warner C, Willadsen S. Ooplasmic transfer in mature human oocytes., 1998, 4(3): 269–280.

[91] Templeton A. Ooplasmic transfer--proceed with care., 2002, 346(10): 773–775.

[92] Sharpley MS, Marciniak C, Eckel-Mahan K, McManus M, Crimi M, Waymire K, Lin CS, Masubuchi S, Friend N, Koike M, Chalkia D, MacGregor G, Sassone-Corsi P, Wallace DC. Heteroplasmy of mouse mtDNA is genetically unstable and results in altered behavior and cognition., 2012, 151(2): 333–343.

[93] Woods DC, Tilly JL. Autologous germline mitochondrial energy transfer (AUGMENT) in human assisted reproduction., 2015, 33(6): 410–421.

[94] Sheng X, Yang Y, Zhou J, Yan G, Liu M, Xu L, Li Z, Jiang R, Diao Z, Zhen X, Ding L, Sun H. Mitochondrial transfer from aged adipose-derived stem cells does not improve the quality of aged oocytes in C57BL/6 mice., 2019, 86(5): 516–529.

[95] Elfayomy AK, Almasry SM, El-Tarhouny SA, Eldomiaty MA. Human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells transplantation renovates the ovarian surface epithelium in a rat model of premature ovarian failure: possible direct and indirect effects., 2016, 48(4): 370–382.

[96] Lai D, Wang F, Yao X, Zhang Q, Wu X, Xiang C. Human endometrial mesenchymal stem cells restore ovarian function through improving the renewal of germline stem cells in a mouse model of premature ovarian failure., 2015, 13: 155.

[97] Guan J, Zhu Z, Zhao RC, Xiao Z, Wu C, Han Q, Chen L, Tong W, Zhang J, Han Q, Gao J, Feng M, Bao X, Dai J, Wang R. Transplantation of human mesenchymal stem cells loaded on collagen scaffolds for the treatment of traumatic brain injury in rats., 2013, 34(24): 5937–5946.

[98] Su J, Ding L, Cheng J, Yang J, Li X, Yan G, Sun H, Dai J, Hu Y. Transplantation of adipose-derived stem cells combined with collagen scaffolds restores ovarian function in a rat model of premature ovarian insufficiency., 2016, 31(5): 1075–1086.

[99] Truman AM, Tilly JL, Woods DC. Ovarian regeneration: the potential for stem cell contribution in the postnatal ovary to sustained endocrine function., 2017, 445: 74–84.

[100] Zhang C, Wu J. Production of offspring from a germline stem cell line derived from prepubertal ovaries of germline reporter mice., 2016, 22(7): 457–464.

[101] Ding L, Yan G, Wang B, Xu L, Gu Y, Ru T, Cui X, Lei L, Liu J, Sheng X, Wang B, Zhang C, Yang Y, Jiang R, Zhou J, Kong N, Lu F, Zhou H, Zhao Y, Chen B, Hu Y, Dai J, Sun H. Transplantation of UC-MSCs on collagen scaffold activates follicles in dormant ovaries of POF patients with long history of infertility., 2018, 61(12): 1554–1565.

[102] Reddy P, Adhikari D, Zheng W, Liang S, Hämäläinen T, Tohonen V, Ogawa W, Noda T, Volarevic S, Huhtaniemi I, Liu K. PDK1 signaling in oocytes controls reproductive aging and lifespan by manipulating the survival of primordial follicles., 2009, 18(15): 2813–2824.

Advances in the study of ovarian dysfunction with aging

Chuanming Liu1, Lijun Ding1,2, Jiayin Li3, Jianwu Dai3, Haixiang Sun1

Societal changes regarding the role of women have significant impacts on women’s willingness and the timing of childbearing. Ovarian reserve in woman typically begins to decline at the age of 35, and it is primarily characterized by a reduction in the number of ovarian follicles and a decline in oocyte quality. The clinical diagnosis of ovarian insufficiency relies on multiple variables including changes of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), inhibin B, antral follicle count, menstruation and age. It is proven that ovarian cells demonstrate dysfunction associated with aging including mitochondrial dysfunction, telomere shortening, impaired DNA repair, epigenetic changes and metabolic/energetic disorders. In this review, we introduce the clinical diagnosis and management of ovarian insufficiency. We mainly discuss the molecular mechanism and potential interventions.We are optimistic that this information and knowledge will inform the important decisions for women and society regarding childbearing.

ovarian; aging; mitochondrion; heredity; epigenomics

2019-06-28;

2019-07-16

国家重点研发计划“生殖健康及重大出生缺陷防控研究”专项(编号:2018YFC1004700)和中科院战略先导科技专项(编号:XDA01030501)资助[Supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFC1004700) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDA01030501)]

刘传明,博士,研究方向:生殖医学。E-mail: 15950562099@163.com

孙海翔,博士,教授,博士生导师,研究方向:生殖医学。E-mail: stevensunz@163.com

戴建武,博士,研究员,博士生导师,研究方向:再生医学。E-mail: jwdai@genetics.ac.cn

10.16288/j.yczz.19-134

2019/8/12 14:49:54

URI: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.1913.R.20190812.1449.002.html

(责任编委: 史庆华)