早产儿补充长链多不饱和脂肪酸对支气管肺发育不良和坏死性小肠结肠炎发生率影响的系统评价和Meta分析

2015-05-04崔其亮严彩满

王 潜 崔其亮 严彩满

·论著·

早产儿补充长链多不饱和脂肪酸对支气管肺发育不良和坏死性小肠结肠炎发生率影响的系统评价和Meta分析

王 潜 崔其亮 严彩满

目的 定量评价早产儿补充长链多不饱和脂肪酸(LCPUFA)能否降低坏死性小肠结肠炎(NEC)、支气管肺发育不良(BPD)等的发生率。方法 计算机检索PubMed、EMBASE、the Cohrane Library、万方数据库和中国知网,获得早产儿补充LCPUFA对NEC、BPD、严重感染(败血症)和病死率影响的RCT文献,检索时限均从建库至2015年8月27日。由2名研究者独立行文献筛选、资料提取,采用改良JADAD量表评价纳入文献的偏倚风险。以相对危险度(RR)及其95%CI作为效应指标。采用RevMan 5.3软件行Meta分析,根据异质性检验结果选择相应的效应模型合并效应量。结果 15篇RCT文献(n=2 658)进入Meta分析。13篇文献JADAD评分5~7分,2篇文献<5分,总体偏倚风险不大。Meta结果显示,早产儿补充与未补充LCPUFA组的NEC、BPD、严重感染(败血症)和病死率差异均无统计学意义,其RR及其95%CI分别为1.16(0.73~1.83)、0.94(0.79~1.13)、1.13(0.93~1.37)和1.15(0.56~2.36)。以胎龄行亚组分析,胎龄≤32周早产儿补充和未补充LCPUFA的NEC发生率差异有统计学意义,RR=0.42(95%CI: 0.19~0.96),BPD和严重感染(败血症)发生率在胎龄≤32周早产儿补充和未补充LCPUFA间差异均无统计学意义。结论 早产儿补充LCPUFA不能降低BPD、严重感染(败血症)的发生率和病死率,可能降低胎龄≤32周早产儿NEC发生率。

早产儿; 二十二碳六烯酸; 坏死性小肠结肠炎; 支气管肺发育不良; 败血症; 病死率; 系统评价;Meta分析

早产儿尤其是胎龄≤32周早产儿有较高的坏死性小肠结肠炎(NEC)、支气管肺发育不良(BPD)、严重感染(败血症)发生率和病死率 。长链多不饱和脂肪酸(LCPUFA),尤其是二十二碳六烯酸(DHA)和二十碳五烯酸(EPA)是视网膜和中枢神经系统细胞膜的重要组成部分[1,2]。但早产儿在母体内脂质合成以及贮藏数量不足,且将α-亚油酸(ALA)合成DHA的能力也十分有限[3,4]。既往新生儿补充LCPUFA尤其是DHA的研究多关注其促进大脑发育和视觉敏锐度。近年研究提示早产儿补充LCPUFA与炎性反应的负调节密切相关[5],推测早产儿尤其是胎龄≤32周早产儿补充LCPUFA可抑制炎性反应,从而可能降低NEC和BPD等发生率。为此本研究系统检索早产儿补充LCPUFA的RCT研究,对NEC、BPD等指标行定量综合。

1 方法

1.1 文献纳入标准 ①RCT研究,干预组为哺乳期添加DHA、AA等LCPUFA,对照组为未添加或相比较干预组低剂量添加LCPUFA[5~7]的配方奶;②研究对象为胎龄<37周早产儿,可以行母乳或配方粉喂养;③文献描述了NEC、BPD和严重感染(败血症)的诊断标准;④报道了本文设定的结局指标;⑤语种不限。

1.2 文献排除标准 ①非添加DHA、AA为主的LCPUFA;②患严重宫内感染、产伤、电解质紊乱、遗传代谢性疾病、严重先天性呼吸道畸形和严重先天性心脏病患儿。

1.3 结局指标 NEC、BPD和严重感染(败血症)发生率,病死率(任何原因导致的死亡)。

1.4 文献检索策略 检索PubMed、EMBASE、the Cohrane Library、万方数据库和中国知网,获得早产儿补充LCPUFA的RCT文献,检索时间均为建库至2015年8月27日。同时回溯纳入文献的参考文献。

英文检索词:long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid、docosahexaenoic acid、preterm、premature、randomized controlled trial。

以PubMed数据库为例的检索式为:(((((((docosahexaenoic acid) OR omega 3) OR LCPUFA) OR long chain poly unsaturated fatty acid) OR DHA) OR fish oil) OR “Fish Oils”[Mesh〗) OR “docosahexaenoic acids”[Mesh])AND (((“premature birth”[Mesh]) OR “infant, extremely premature”[Mesh]) OR “infant, premature”[Mesh]) AND (randomized controlled trial[Publication type]) OR controlled clinical trial[Publication type])。

中文检索词:长链多不饱和脂肪酸、二十二碳六烯酸、早产、随机对照试验。

以万方数据库为例的检索式为:“长链不饱和脂肪酸”AND “早产” AND“随机对照试验”。

1.5 文献筛选、资料提取和偏倚风险评价 由王潜、严彩满独立行文献筛选、提取资料和文献偏倚风险评价,并交叉核对,如遇分歧,由崔其亮决定。提取资料包括:①纳入研究的基本信息:第一作者、发表年份和国家;②研究对象的基本特征:各组病例数、胎龄、出生体重和干预时间等;③偏倚风险评价内容;④结局指标。

采用改良版JADAD量表行文献偏倚风险评价:随机序列的产生、分配隐藏、盲法、退出和理由,其中随机序列的产生、分配隐藏和盲法以“否”、“不清楚”和“是”描述,分别赋0、1和2分;退出和理由以“否”和“是”描述,分别评0和1分。>5分为低度偏倚风险。

1.6 统计学方法 采用RevMan 5.2软件行Meta分析,以RR及其95%CI作为效应指标。对文献行异质性检验,若无统计学异质性(I2<50%)采用固定效应模型,若有统计学异质性(I2≥50%)则采用随机效应模型。P<0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果

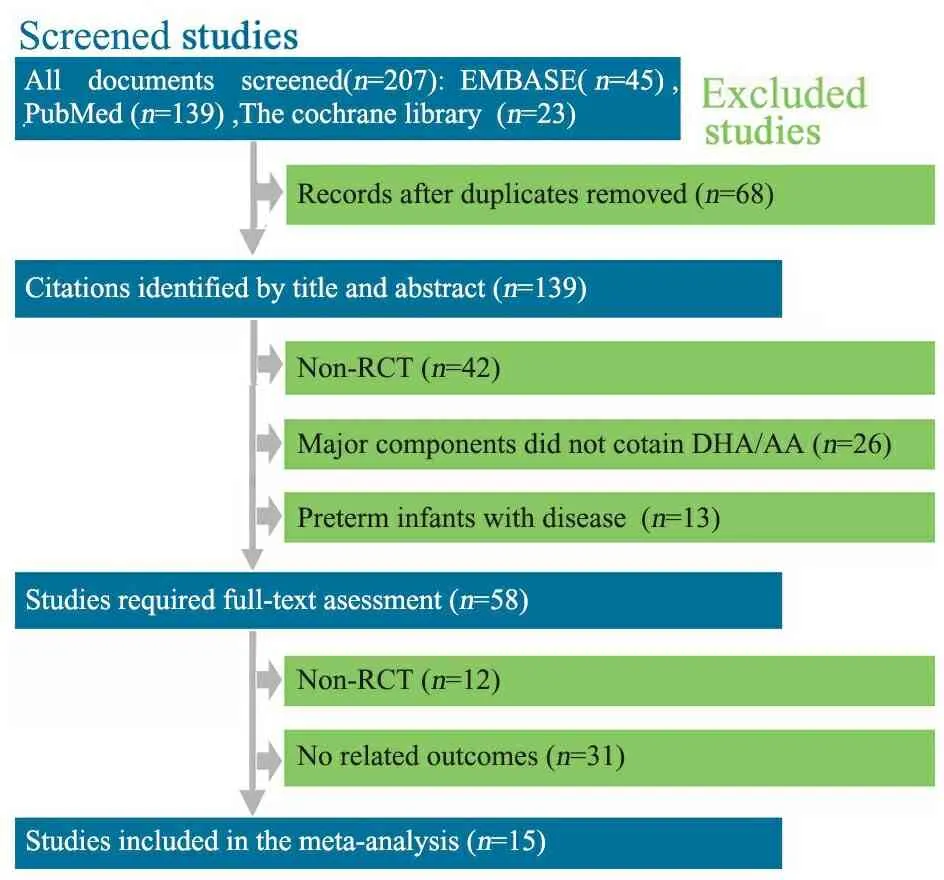

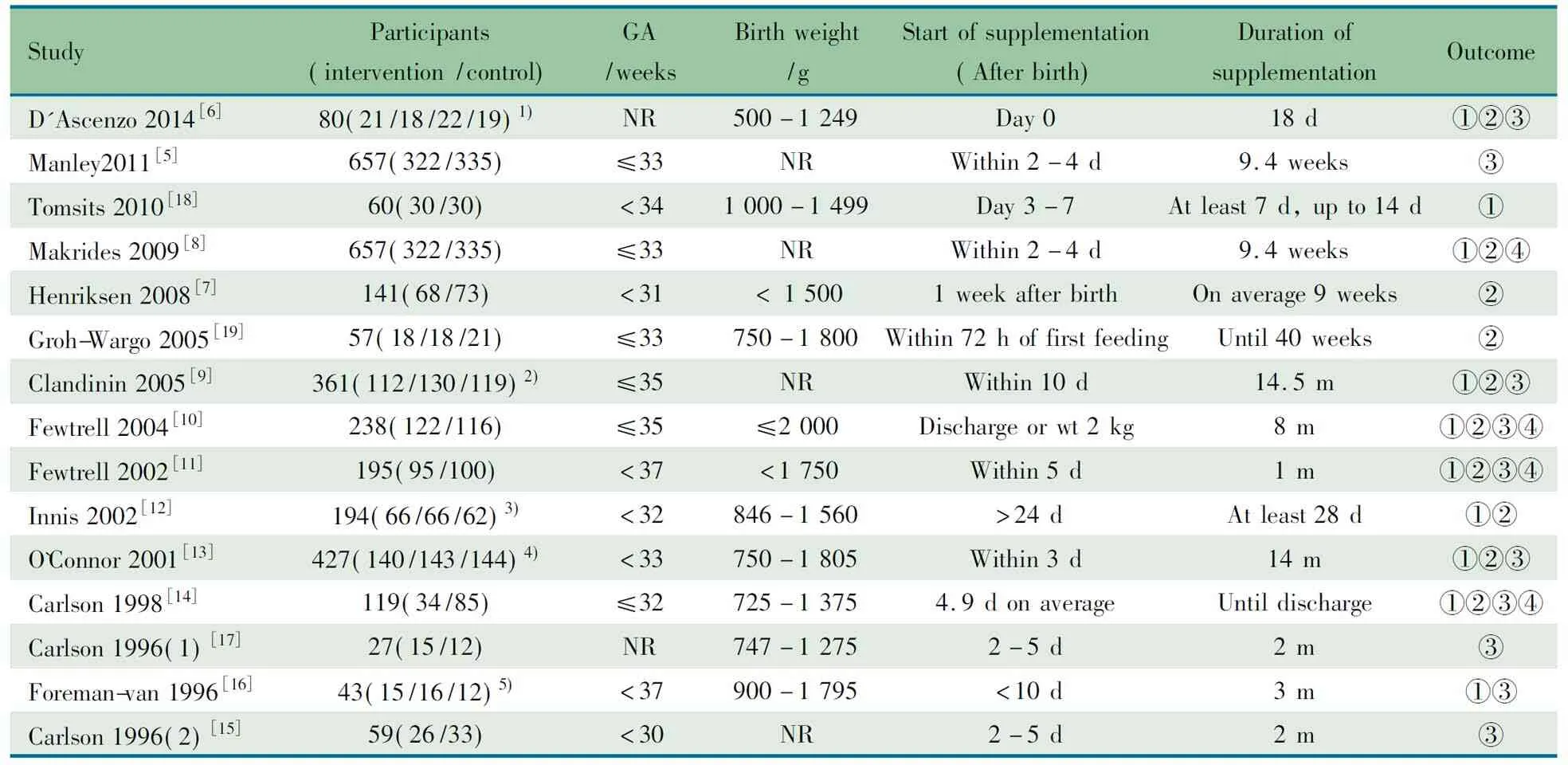

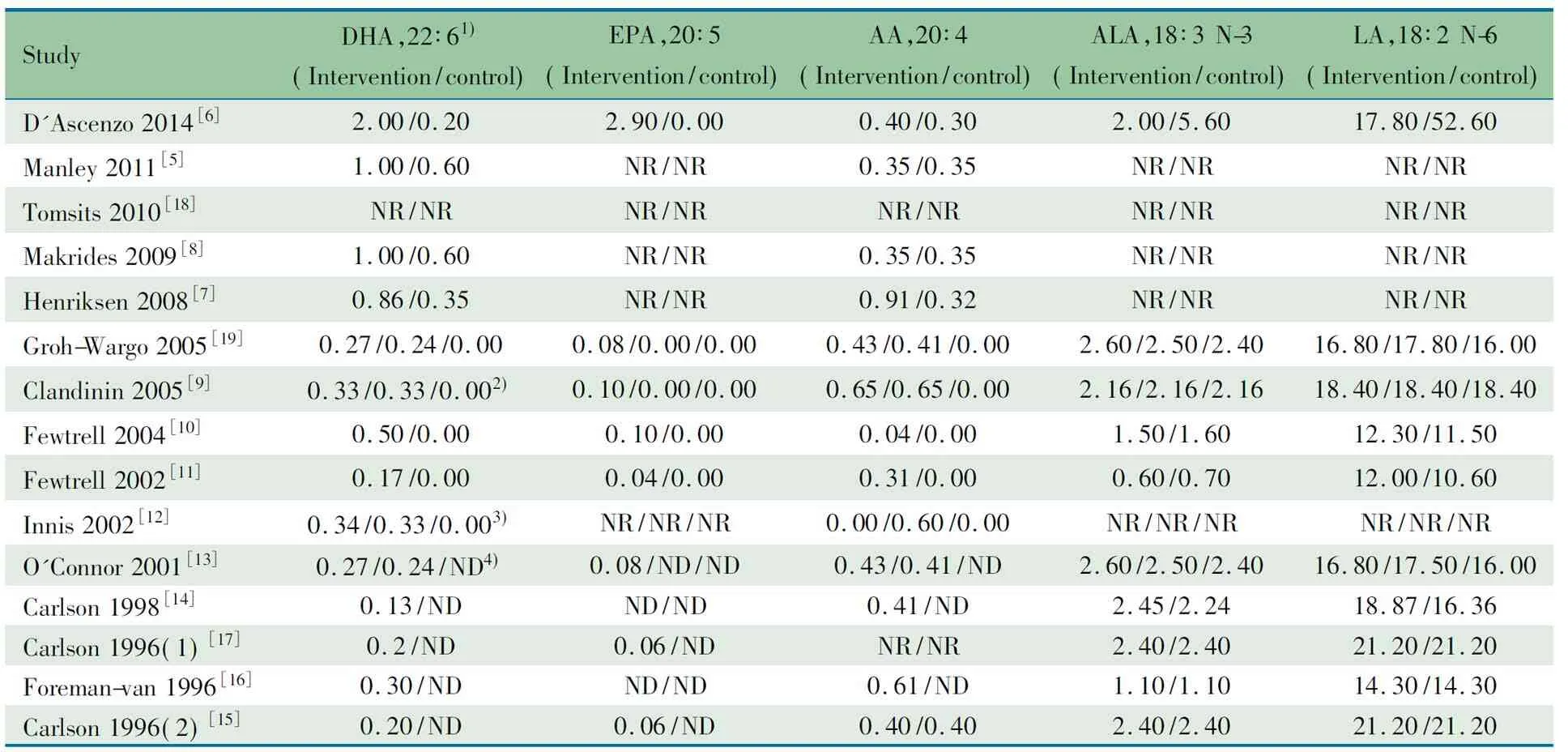

2.1 检索的一般情况 初步检索到207篇文献,15篇RCT文献[5~19]进入本文Meta分析(图1),共纳入2 658例早产儿。15篇RCT文献来自于欧洲、北美洲和中国台湾等。8篇文献的研究对象胎龄≤32周或出生体重<1 500 g[6, 7, 12~15, 17,18]。除文献[12]外,余14篇文献早产儿均于生后10 d内予LCPUFA干预,15篇文献采用补充添加或未添加LCPUFA的配方奶,或将外观相同的鱼油丸或豆油丸混入配方奶中。纳入文献的基本特征见表1。

除文献[18]外,余文献均标注了干预组与对照组ω-3 LCPUFA以及ω-6 LCPUFA的浓度,ω-3 LCPUFA以DHA、EPA和ALA为主,ω-6 LCPUFA以AA和LA为主(表2)。

图1 文献筛选流程图

Notes 1) MOSF-2.5Fat/MOSF-3.5Fat/S-2.5Fat/S-3.5Fat; 2) algal-DHA supplement group/fish-DHA supplement group/control group; 3) DHA group/DHA+ARA group/control group; 4) (fish/fungal oil group)/(egg-TG/fish oil)/control group; 5) LCP-enriched formula group/conventional formula group/human milk group. GA: gestational age; NR: not reported; ①: infection (spesis); ②necrotizing enterocolitis; ③bonchopulmonary dysplasia; ④: death

表2 纳入文献LCPUFA的配方(%)

Notes 1) Doses are defined in g/100 g of fatty acid; 2) algal-DHA supplement group/Fish-DHA supplement group/control group; 3) DHA group/DHA+ARA group/control group; 4) (fish/fungal oil group)/(egg-TG/fish oil)/control group; NR: not reported; ND: not done

2.2 文献偏倚评价结果 7篇文献[5,7~9,12,13,16]描述了随机序列的产生方法,余文献未提及;7篇文献[5,6,8,10,11,14,17]描述了随机序列的分配隐藏,7篇文献[7,9,12,13,15,16,19]未描述,文献[18]未采用分配隐藏;11篇文献[5~11,13~15,17]采用盲法,3篇文献[12,16,18]未提及,文献[19]未采用盲法;15篇文献均描述了失访。2篇[5,8]文献评为7分,8篇文献[6,7,9~11,13,14,17]评为6分,3篇文献[12,15,16]评为5分,文献[18,19]评为3分。

2.3 Meta分析结果

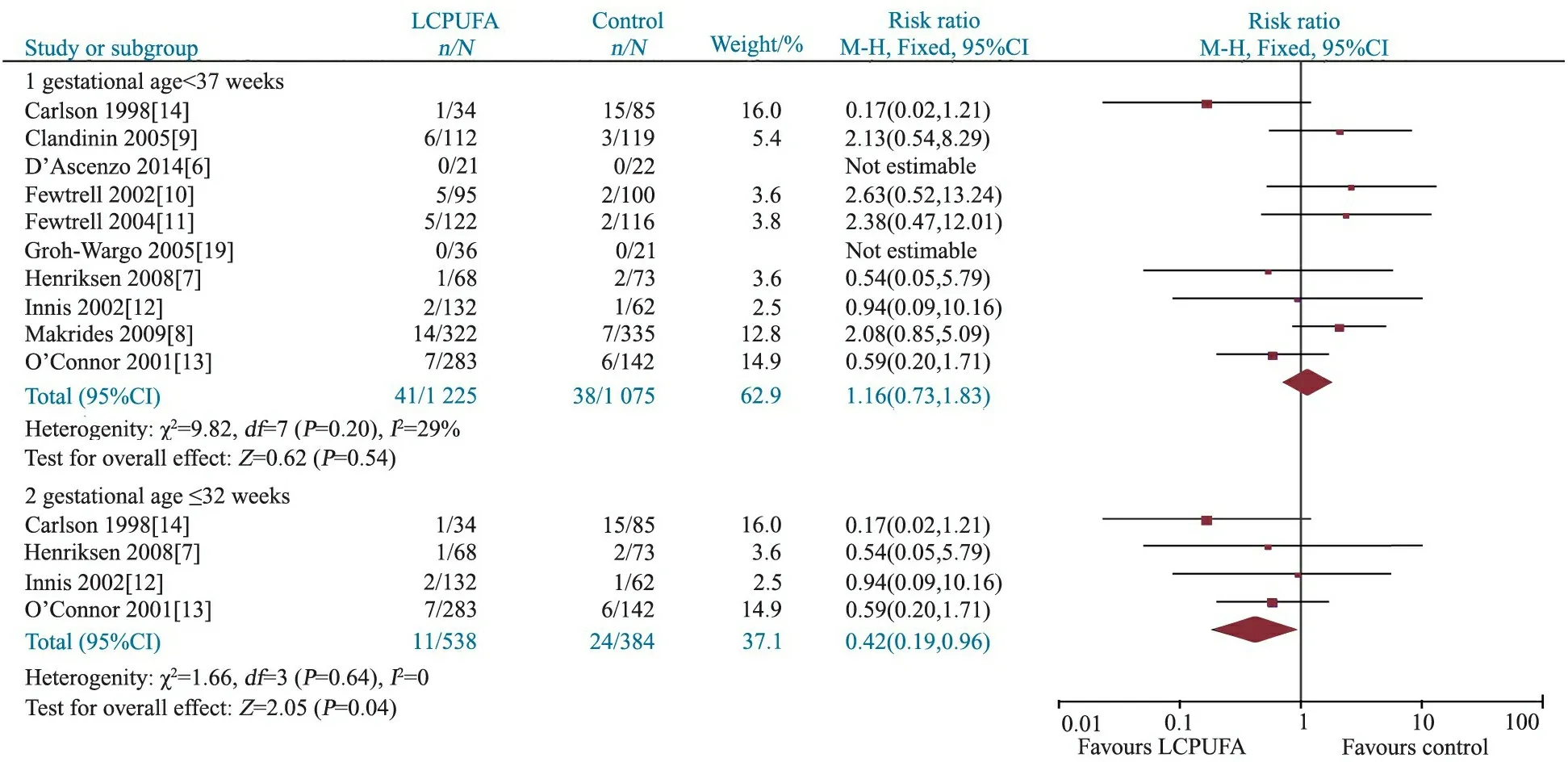

2.3.1 NEC发生率 10篇文献[6~14, 19]报道了两组NEC发生率,异质性检验P=0.20,固定效应模型Meta分析结果显示,干预组和对照组NEC的发生率差异无统计学意义,RR=1.16,95%CI:0.73~1.83,P=0.54(图2,胎龄<37周)。

2.3.2 BPD发生率 10篇文献[5, 6, 9~11, 13~17]报道了两组BPD发生率,异质性检验P=0.30,采用固定效应模型合并结果,Meta分析结果显示,干预组和对照组BPD的发生率差异无统计学意义,RR=0.94, 95%CI:0.79~1.13,P=0.53(图3,胎龄<37周)。

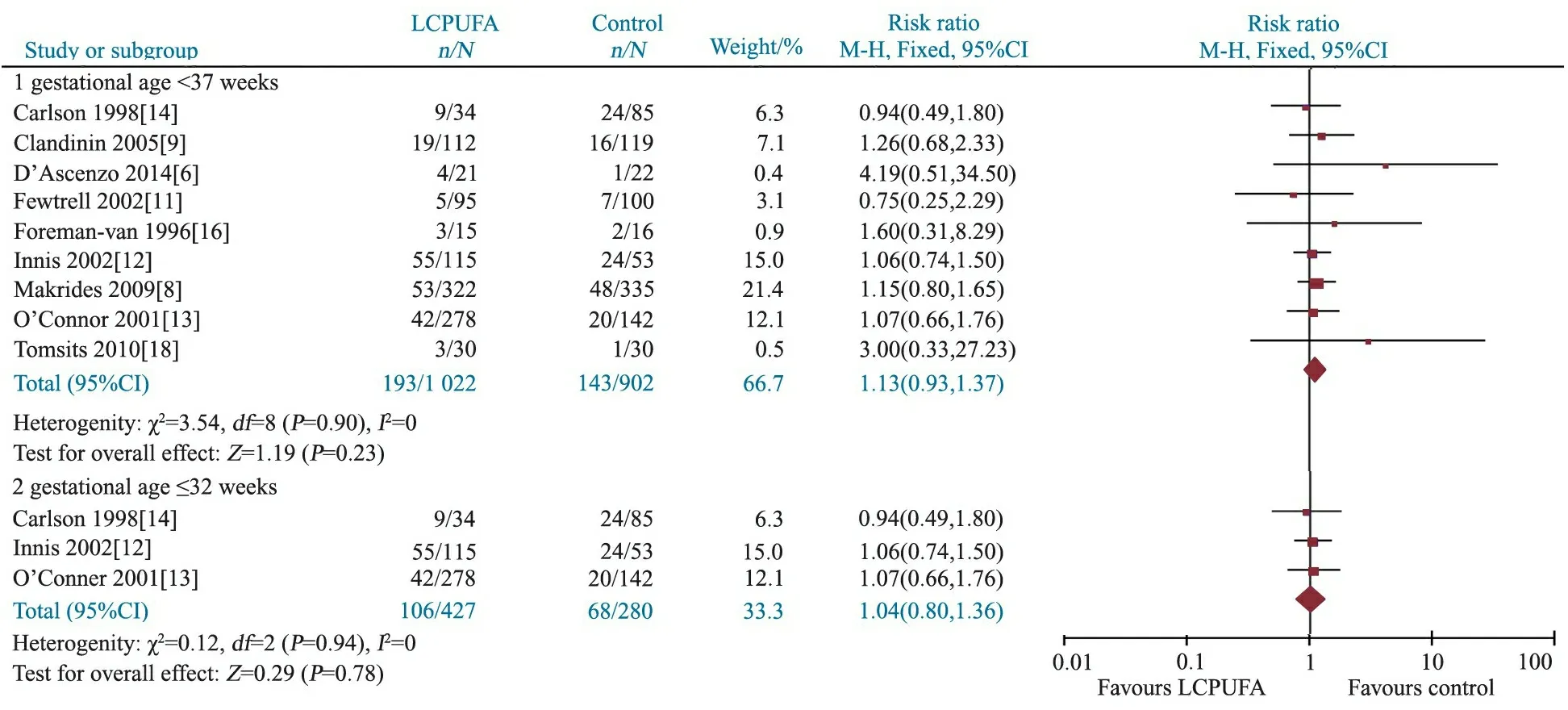

2.3.3 严重感染(败血症)发生率 9篇文献[6, 8~14, 16, 18]报道了两组严重感染(败血症)发生率,异质性检验P=0.90,采用固定效应模型合并结果,Meta分析结果显示,干预组和对照组严重感染(败血症)的发生率差异无统计学意义,RR=1.13, 95%CI:0.93~1.37,P=0.23(图4,胎龄<37周)。

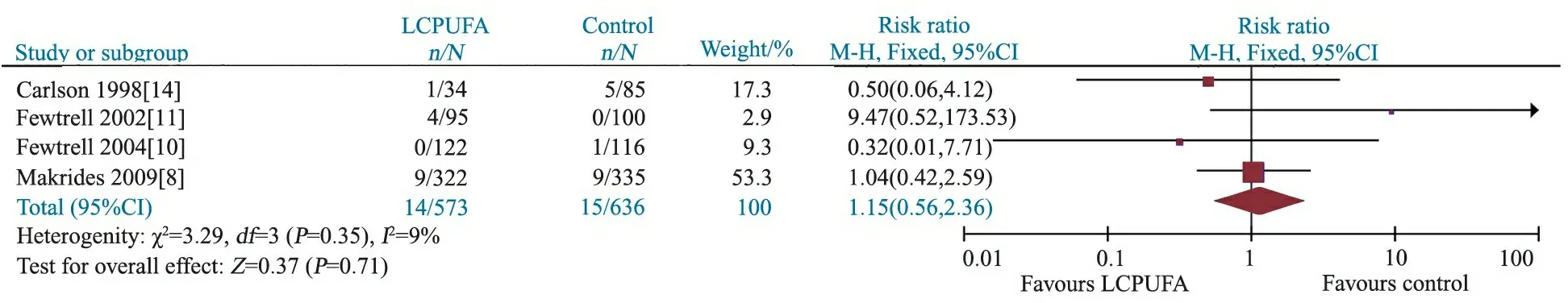

2.3.4 病死率 4篇文献[8, 10, 11, 14]报道了病死率,异质性检验P=0.35,采用固定效应模型合并结果,Meta分析结果显示,干预组和对照组病死率差异无统计学意义,RR=1.15, 95%CI:0.56~2.36,P=0.71(图5)。

2.3.5 亚组分析 图2显示,胎龄≤32周早产儿补充和未补充LCPUFA的NEC发生率差异有统计学意义,RR=0.42(95%CI: 0.19~0.96);图3和4显示,BPD和严重感染(败血症)发生率在胎龄≤32周早产儿补充和未补充LCPUFA间差异均无统计学意义。

图3 LCPUFA干预组和对照组BPD发生率的Meta分析

图4 LCPUFA干预组和对照组严重感染(败血症)发生率的Meta分析

图5 LCPUFA干预组和对照组病死率的Meta分析

Fig 5 Meta-analysis of the mortality in LCPUFA and control groups

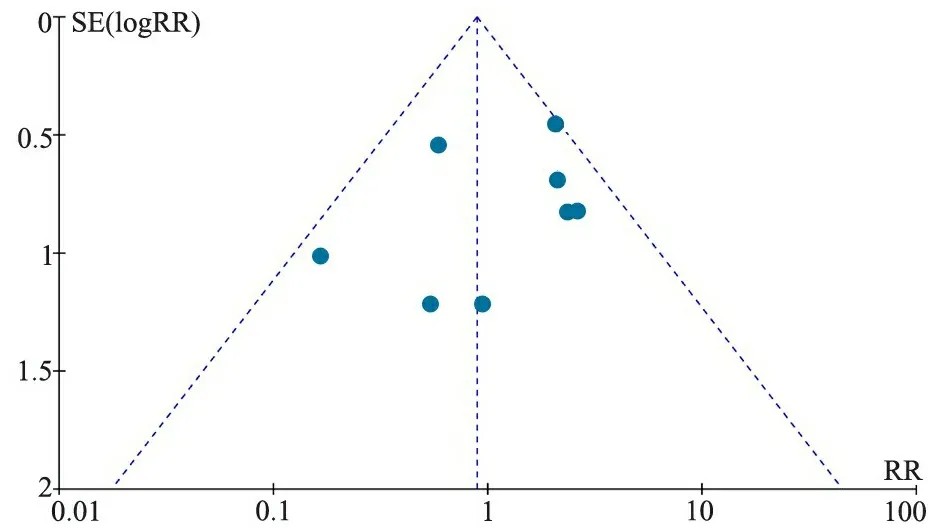

2.4 发表偏倚 以报道NEC发生率的文献绘制漏斗图(图6),显示漏斗图对称,提示发表偏倚的可能性不大。

图6 NEC文献发表偏倚的漏斗图

Fig 6 Funnel plot of studies regarding NEC

3 讨论

本文Meta分析纳入的15篇RCT文献,采用改良JADAD量表行偏倚风险评价,7篇文献描述随机序列产生的方法,8篇文献采用分配隐藏,11篇文献采用盲法,均报道了失访情况,13篇文献评分在5~7分,2篇文献<5分,因此本文纳入文献的偏倚风险较低。

以DHA为主的LCPUFA广泛存在于大脑皮质(足月儿约23%)、肌肉和脂肪组织[20],早产儿体内DHA贮存量低于足月儿10%[21]。研究表明,极早产儿每日DHA的需求量40~60 mg·kg-1。ALA是体内代谢DHA的关键脂肪酸,可通过去饱和-延伸途径合成DHA和EPA[22]。由于早产儿体内脂肪贮存量少、生长发育的需求量大和体内合成功能不足等因素,可导致早产儿缺乏DHA。有研究显示,早产儿尤其行机械通气、长期氧疗者的炎性反应生物标志物水平高于正常足月儿,而持续的氧化应激以及炎性反应是BPD、NEC等新生儿疾病发生不可忽视的原因[23~25]。补充LCPUFA尤其是DHA与EPA对炎性反应有非常重要的调节作用[26~33]。

本文Meta分析结果显示,早产儿补充LCPUFA不能降低BPD、严重感染(败血症)的发生率和病死率;但以胎龄行亚组分析显示,补充LCPUFA可能降低胎龄≤32周早产儿NEC发生率,RR=0.42(95%CI:0.19~0.96),与多项观察性研究的结果相近[34~36]。但本文亚组分析的NEC的文献为4篇,结局事件的发生例数少,且结果存在显著的不精确性,因此仍需补充研究进一步明确。

本文分析的4个指标异质性检验P均>0.1,提示文献间具同质性;但本文纳入文献间存在一定的临床异质性,如干预组中的LCPUFA或来源于鱼油或海藻油,而喂养载体或为母乳或配方奶,但限于文献量有限,未行分层分析。4篇文献对照组为添加较低浓度的LCPUFA,可能对结果有一定影响。

结论:早产儿补充LCPUFA不能降低BPD、严重感染(败血症)的发生率和病死率,可能降低胎龄≤32周早产儿NEC发生率。

[1]Kidd PM. Omega-3 DHA and EPA for cognition, behavior, and mood: clinical findings and structural-functional synergies with cell membrane phospholipids. Altern Med Rev, 2007,12(3):207-227

[2]Farooqui AA, Horrocks LA, Farooqui T. Modulation of inflammation in brain: a matter of fat. J Neurochem, 2007,101(3):577-599

[3]Zhang P, Lavoie PM, Lacaze-Masmonteil T, et al. Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids for extremely preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatrics, 2014,134(1):120-134

[4]Qawasmi A, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Leckman JF, et al. Meta-analysis of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation of formula and infant cognition. Pediatrics, 2012,129(6):1141-1149

[5]Manley BJ, Makrides M, Collins CT, et al. High-dose docosahexaenoic acid supplementation of preterm infants: respiratory and allergy outcomes. Pediatrics, 2011,128(1):71-77

[6]D′Ascenzo R, Savini S, Biagetti C, et al. Higher docosahexaenoic acid, lower arachidonic acid and reduced lipid tolerance with high doses of a lipid emulsion containing 15% fish oil: a randomized clinical trial.Clin Nutr, 2014,33(6):1002-1009

[7]Henriksen C, Haugholt K, Lindgren M, et al. Improved cognitive development among preterm infants attributable to early supplementation of human milk with docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid. Pediatrics, 2008,121(6):1137-1145

[8]Makrides M, Gibson RA, McPhee AJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants fed high-dose docosahexaenoic acid: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 2009,301(2):175-182

[9]Clandinin MT, Van Aerde JE, Merkel KL, et al. Growth and development of preterm infants fed infant formulas containing docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid. J Pediatr, 2005,146(4):461-468

[10]Fewtrell MS, Abbott RA, Kennedy K, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with fish oil and borage oil in preterm infants. J Pediatr, 2004,144(4):471-479

[11]Fewtrell MS, Morley R, Abbott RA, et al. Double-blind, randomized trial of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in formula fed to preterm infants. Pediatrics, 2002,110(1 Pt 1):73-82

[12]Innis SM, Adamkin DH, Hall RT, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid enhance growth with no adverse effects in preterm infants fed formula. J Pediatr, 2002,140(5):547-554

[13]O′Connor DL, Hall R, Adamkin D, et al. Growth and development in preterm infants fed long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 2001,108(2):359-371

[14]Carlson SE, Montalto MB, Ponder DL, et al. Lower incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in infants fed a preterm formula with egg phospholipids. Pediatr Res, 1998,44(4):491-498

[15]Carlson SE, Werkman SH. A randomized trial of visual attention of preterm infants fed docosahexaenoic acid until two months. Lipids, 1996,31(1):85-90

[16]Foreman-van DM, van Houwelingen AC, Kester AD, et al. Influence of feeding artificial-formula milks containing docosahexaenoic and arachidonic acids on the postnatal long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid status of healthy preterm infants. Br J Nutr, 1996,76(5):649-667

[17]Carlson SE, Werkman SH, Tolley EA. Effect of long-chain n-3 fatty acid supplementation on visual acuity and growth of preterm infants with and without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Clin Nutr, 1996,63(5):687-697

[18]Tomsits E, Pataki M, Tolgyesi A, et al. Safety and efficacy of a lipid emulsion containing a mixture of soybean oil, medium-chain triglycerides, olive oil, and fish oil: a randomised, double-blind clinical trial in premature infants requiring parenteral nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2010,51(4):514-521

[19]Groh-Wargo S, Jacobs J, Auestad N, et al. Body composition in preterm infants who are fed long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatr Res, 2005,57(5 Pt 1):712-718

[20]Kuipers RS, Luxwolda MF, Offringa PJ, et al. Fetal intrauterine whole body linoleic, arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid contents and accretion rates. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids, 2012,86(1-2):13-20

[21]Foreman-van DM, van Houwelingen AC, Kester AD, et al. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in preterm infants: status at birth and its influence on postnatal levels. J Pediatr, 1995,126(4):611-618

[22]Carnielli VP, Wattimena DJ, Luijendijk IH, et al. The very low birth weight premature infant is capable of synthesizing arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids from linoleic and linolenic acids. Pediatr Res, 1996,40(1):169-174

[23]Chang BA, Huang Q, Quan J, et al. Early inflammation in the absence of overt infection in preterm neonates exposed to intensive care. Cytokine, 2011,56(3):621-626

[24]Lavoie PM, Lavoie JC, Watson C, et al. Inflammatory response in preterm infants is induced early in life by oxygen and modulated by total parenteral nutrition. Pediatr Res, 2010,68(3):248-251

[25]Paananen R, Husa AK, Vuolteenaho R, et al. Blood cytokines during the perinatal period in very preterm infants: relationship of inflammatory response and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr, 2009,154(1):39-43

[26]Valentine CJ. Maternal dietary DHA supplementation to improve inflammatory outcomes in the preterm infant. Adv Nutr, 2012,3(3):370-376

[27]Clandinin MT, Larsen BM. Docosahexaenoic acid is essential to development of critical functions in infants. J Pediatr, 2010,157(6):875-876

[28]Miloudi K, Comte B, Rouleau T, et al. The mode of administration of total parenteral nutrition and nature of lipid content influence the generation of peroxides and aldehydes. Clin Nutr, 2012,31(4):526-534

[29]Chao AC, Ziadeh BI, Diau GY, et al. Influence of dietary long-chain PUFA on premature baboon lung FA and dipalmitoyl PC composition. Lipids, 2003,38(4):425-429

[30]Rogers LK, Valentine CJ, Pennell M, et al. Maternal docosahexaenoic acid supplementation decreases lung inflammation in hyperoxia-exposed newborn mice. J Nutr, 2011,141(2):214-222

[31]Caplan MS, Russell T, Xiao Y, et al. Effect of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) supplementation on intestinal inflammation and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in a neonatal rat model. Pediatr Res, 2001,49(5):647-652

[32]Balvers MG, Verhoeckx KC, Plastina P, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid are converted by 3T3-L1 adipocytes to N-acyl ethanolamines with anti-inflammatory properties. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2010,1801(10):1107-1114

[33]Saccone G, Berghella V. Omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids to prevent preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol, 2015,125(3):663-672

[34]Martin CR, Dasilva DA, Cluette-Brown JE, et al. Decreased postnatal docosahexaenoic and arachidonic acid blood levels in premature infants are associated with neonatal morbidities. J Pediatr, 2011,159(5):743-749

[35]Marc I, Plourde M, Lucas M, et al. Early docosahexaenoic acid supplementation of mothers during lactation leads to high plasma concentrations in very preterm infants. J Nutr, 2011,141(2):231-236

[36]Skouroliakou M, Konstantinou D, Agakidis C, et al. Cholestasis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and lipid profile in preterm infants receiving MCT/omega-3-PUFA-containing or soybean-based lipid emulsions. Nutr Clin Pract, 2012,27(6):817-824

(本文编辑:丁俊杰)

The impact of LCPUFA supplement on incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis

WANGQian,CUIQi-liang,YANCai-man

(TheThirdAffiliatedHospitalofGuangzhouMedicalUniversity,Guangzhou510630,China)

CUI Qi-liang,E-mail:gycuiqiliang@126.com

ObjectiveTo compare the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis(NEC), bronchopulmonary dysplasia(BPD) and other neonatal disease between preterm infants received LCPUFA-supplemented formula and regular formula.MethodsThe databases of PubMed,EMBASE,the Cohrane Library, CNKI and Wanfang database were searched from establishment to Augest, 2015, to collect relevant studies investigating the impact of preterm infants given LCPUFA on the incidence of NEC, BPD, sepsis and mortality. Two reviewers independently screened literatures, extracted data,and assessed the risk bias of included studies by modified JADAD scale, including randomization, concealing, blinding and loss of follow up. The outcomes were expressed as risk ratio(RR) with 95% CI.The meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.3 software.A fixed-effect model or a random-effect model would be used according to the heterogeneity test results.ResultsFifteen RCTs (2 658 infants) were included into this meta-analysis. The JADAD score of 13 RCTs ranged from 5 to 7, whearas 2 RCTs < 5, which indicated the risk of bias of included studies was low. The meta-analysis showed that LCPUFA could not significantly decrease the incidence of NEC, BPD, sepsis or death, the correponding RR(95%CI) was 1.16(0.73-1.83), 0.94(0.79-1.13), 1.13(0.93-1.37) and 1.15(0.56-2.36), respectively. Subgroup analysis found that preterm infants with gestational age ≤32 weeks receiving LCPUFA had lower incidence of NEC (RR,0.42,95% CI: 0.19-0.96). The incidences of BPD and sepsis did not significantly differ in infants reveiving and non-reveiving LCPUFA in the gestational age ≤32 weeks. ConclusionPreterm infants received LCPUFA-supplemented formula could not decrease the incidence of BPD, sepsis and death, however may decrease the incidence of NEC in infants with gestational age less than 32 weeks.

Preterm infant; Docosahexaenoic acid; Necrotizing enterocolitis; Bronchopulmonary dysplasia; Sepsis; Mortality; Systematic review; Meta analysis

广州医科大学附属第三医院 广州,510630

崔其亮,E-mail:gycuiqiliang@126.com

10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2015.06.005

2015-08-15

2015-11-16)