以色列内盖夫沙漠的发现对黎凡特石器工业来源与去向的启示

2023-04-29OmryBARZILAI

Omry BARZILAI

摘要:旧石器时代晚期初段,系统剥取石叶尖状器技术开始出现并见于欧亚大陆不同地区,这一现象被认为与MIS 3 阶段现代人的扩张密切相关。黎凡特旧石器时代晚期初段的界定标准源自以色列内盖夫沙漠Boker Tachtit(波克·塔吉特)遗址两组连续叠压的石器工业,遗址下部的Emiran(埃米尔)石器工业以双向剥片石叶技术为特征,上部石器工业则以单向剥片石叶技术为标志。Boker Tachtit 遗址一直缺乏较可靠的年代学基础,但新近放射性测年数据表明Emiran 工业并存于黎凡特本土的莫斯特晚期石器工业,Emiran 工业为外来的推测也由此得到了支持。由于Boker Tachtit 与尼罗河谷地及南阿拉伯地区年代接近的石器工业技术特点相似,早期的Boker Tachtit 人群很可能来自上述区域。Emiran 工业在BokerTachtit 演变为单向剥片石叶工业的同时一直向欧洲中部及亚洲中北部地区扩张。与之类似,单向剥片石叶工业一面向黎凡特北部及巴尔干地区传播,一面在本地发展成为早期Ahamarian(艾玛尔)工业技术体系。因此旧石器时代晚期初段至少发生过两次人群扩散事件,第一次为来自尼罗河流域及阿拉伯半岛人群在迁徙至黎凡特后向欧洲中部与亚洲中北部地区的迅速扩张;第二次事件的发生年代略晚,表现为黎凡特南部人群向黎凡特北部及巴尔干地区的逐步扩散。

关键词:旧石器时代晚期初段;Boker Tachtit;Emiran;石器技术;人群扩散

1 Introduction

The transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic in Eurasia corresponds withdemographic changes, namely the appearance of modern humans alongside with the demise ofNeanderthal populations[1-3]. This process received much attention in the scientific literature eversince the Neanderthals were discovered and defined in the 19th century in Europe[4]. For manyyears, the two populations were conceived as different species with minimal cultural contacts,but recent genetic studies have refuted this notion and proved Neanderthals and modern humansdid biologically interact[5-6].

New advances in the fields of absolute chronology and paleo-genetics proposed modernhumans migrated from Africa to Eurasia numerous times in the period between 200-50 ka[7-9].The latest migration, known also as the "recent out of Africa", was the most influential one andpresumably brought the Neanderthal linage in Eurasia to an end.

While genetic studies determined that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals met and bred, they donot provide the exact timing and locations of these interactions. Moreover, they do offer the pathsof modern human migration, but only very generally. The ultimate means for learning about suchprocesses are, naturally, the human fossil records but they are very rare in archaeological sites. Hence,the common way to discover more about these demographic changes and cultural transformations ispursued by material culture studies. Among these, lithics are by far the most abundant finds and oftencontain formal artifacts which are associated with specific human groups[10-11]. In Middle PaleolithicEurope for example, Levallois core technology, the formal method for producing spear points andhunting-related tools such as scrapers and knives, is associated with Neanderthals.1) On the other1) An exception is the Levantine Middle Paleolithic where Levallois assemblages were produced also by archaic Homo sapiens in MIS 5 hand, Upper Paleolithic blade technologies used for making projectiles, endscrapers and burins areassociated with Homo sapiens, as are bone and antler tools and shell ornaments.

The intermediate phase between the Middle and the Upper Paleolithic is complex andcontains material culture remains which could be ascribed to both species. The lithic assemblagesbear technical properties common to both Upper and Middle Paleolithic technologies.Intermediate assemblages utilize Upper Paleolithic volumetric approach in which the narrowside of the block was used for manufacturing standardized blades. Conversely, the extraction ofthe blades followed Middle Paleolithic modes and gestures, such as platform preparations beforestriking (faceting) and use of a hard hammer stone.

Today it is accepted to include intermediate assemblages under the general nomenclatureof Initial Upper Paleolithic (IUP)[12]. What is not accepted is the identity of the makers of theseindustries. Was this material culture brought in by the migrating modern humans? Or did itdevelop from the local Middle Paleolithic industries of the Neanderthals? An examination of theterminological history of this phase shows that the IUP is not a homogeneous industry but ratherfeatures a more complex cultural sequence.

The aims of this paper are to provide an updated summary on the Levantine IUP and refineour understanding on its chronology, phasing, and implications on MIS 3 human dispersals basedon the new excavation of the site of Boker Tachtit[13].

2 The Levantine Initial Upper Paleolithic

The Initial Upper Paleolithic was originally defined after the uppermost stratigraphic layer(Level 4) at the site of Boker Tachtit in the Negev Desert, Israel[14] (Fig.1). Comprehensive lithicstudies have shown Level 4 at Boker Tachtit evolved in-situ from the lower Levels 1-3, assignedto the Emiran techno-complex. Accordingly, the IUP industry was conceived as a locallydeveloped early Upper Paleolithic industry[15].

The lower levels industry, the Emiran, was defined in the early 20th century by Turville-Petre[16] following his excavation at Emireh Cave, located in the eastern Galilee region ofIsrael (Fig.1). This industry is characterized by a blend of Middle and Upper Paleolithic toolsand includes a diagnostic projectile tool, the Emireh point[17]. Initially, the Emiran phase wasnot accepted by Dorothy Garrod, the preeminent prehistorian in the Near East at that time,who supposed the materials from Emireh Cave constituted mixed Paleolithic deposits. Later,however, Garrod changed her opinion after she identified similar assemblages at the sites of el-Wad Cave, Abu Halka and Ksar Akil[17-19]. A recent study of the lithic assemblage from EmirehCave confirmed both observations made by Garrod: the assemblage was indeed mixed andcontained Middle and Upper Paleolithic components, but also included distinctive components ofbidirectional blade technology and Emireh points[20] (Fig.2:1, 2:3, 2:6).

Following Garrod's new conception of the Emiran this nomenclature was accepted as theearliest phase in the Upper Paleolithic of the southern Levant, and the Emireh point as the 'fossildirecteur used to assigned (or not) assemblages to this industry[21-22]. Presence of Emireh pointsat Qafzeh, e-Tabban, Kebara and Shovakh Caves suggested that this phase existed at other sites in the southern Levant even though their stratigraphies were not clear[17, 23-24] (Fig.1).The discovery of Boker Tachtit in 1974 in the Central Negev Project provided invaluableinformation regarding the lithic technology of the Middle to Upper Paleolithic intermediate phase[25-26].

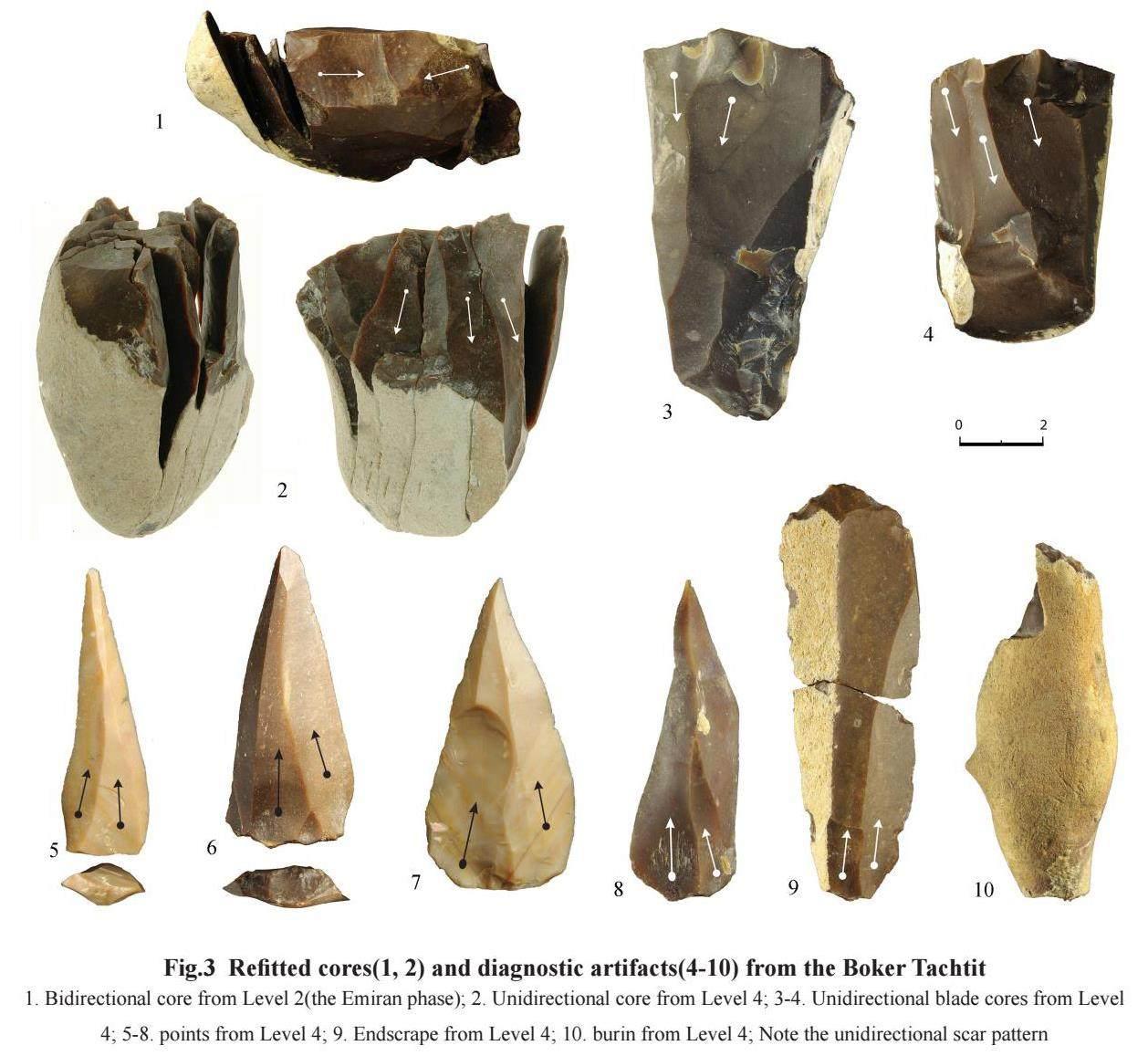

Boker Tachtit is composed of four archaeological horizons, all including well- preservedlithic assemblages with a high refitting ratio (Fig.3: 1-2). Comprehensive lithic studies of thelower levels (1-3), assigned to the Emiran phase, showed the knapping method emphasizedproduction of broad-base blades from bidirectional cores (Fig.2: 2; Fig.3: 1). The blades buttswere subjected to faceting before detachment by hard hammerstone. The Emiran reductionsequence made use of crested blades to establish the removal surface and core tablets forrenovation of the striking platform. The diagnostic tools consisted of Emireh points (Fig.2: 4-5),unretouched points that resemble Levallois, endscrapers and burins.

The upper Level 4 at Boker Tachtit showed technological continuation from the lowerlevels. The major difference from the lower levels is the shift in production of blades frombidirectional to unidirectional (Fig.3: 2-10). The unidirectional core removal surfaces wereestablished by thick primary blades instead of crested blades which were common in the lowerlevels. The blades were subjected to butt preparation and extracted by hard hammerstones. The toolkit remained similar and comprised points, burins and endscrapers (Fig.3: 5-10). Still, thepoints turned narrower and the Emireh points were no longer in use. Despite its common features,Marks separated the new industry from the Emiran and termed it Initial Upper Paleolithic.

Extensive work in the 1980-1990s in southern Jordan revealed more assemblagescorresponding to phase of Boker Tachtit 4 at the sites of Wadi Aghar and Tor Sadaf (Fig.1). In bothsites the unidirectional blade industry was dominant[27-28]. A recent study by Kadowaki and Henry[29]demonstrated systematic use of bladelet technology at Wadi Aghar in addition to the unidirectionalblades (Kadowaki et al in press). Bladelet production from "burin cores" was noted also at thelower level at Boker Tachtit and is conceived as one of the characteristics of the IUP[30].

IUP assemblages were noted at several sites in the Northern Levant. The first sites wherethis phase was recognized were Abu Halka and Ksar Akil in Lebanon. These sites, together withel-Wad and Emireh Caves, were the four sites upon which Garrod proposed a transitional phaseat the lowermost stage of the Levantine Upper Paleolithic[17]. This observation by Garrod wassupported by the technological analyses conducted for two sites by Azoury[31] and Ohnuma[32] and even received the term 'Abu Halkan' by Copeland[33]. Recent work by Leder[34] showed thecommon method for blade production at the two sites was convergent unidirectional blade.

Following his work at Boker Tachtit, Marks reviewed the Ksar Akil assemblages and foundhigh resemblance between Ksar Akil levels XXIII-XXII and Boker Tachtit level 4[35]. The majordifference between Ksar Akil and Boker Tachtit 4 was the presence of a transversal burin type,the chanfrein, in the Ksar Akil assemblages[36].

The existence of the chanfrien along with absence of the Emireh point within the northernassemblages gave a false impression that there are geographical variants in the IUP, butsubsequent discoveries of findspots bearing Emireh points along the Lebanese coast suggest thatthe Emiran phase is also present in the northern Levant[33].

In the 1990's Kuhn recognized assemblages similar to those of Ksar Akil Phase A at??a??zl? Cave[37]. Accordingly, he adopted Marks' term IUP to describe the early occurrence at??a??zl? but at the same time expanded this term to include all transitional assemblages in theLevant, including the Emiran phase[38]. Another site which fits the later phase is Umm el-Tlelwhich is characterized by unidirectional blades and bladelet technologies[39].

3 The IUP absolute chronology

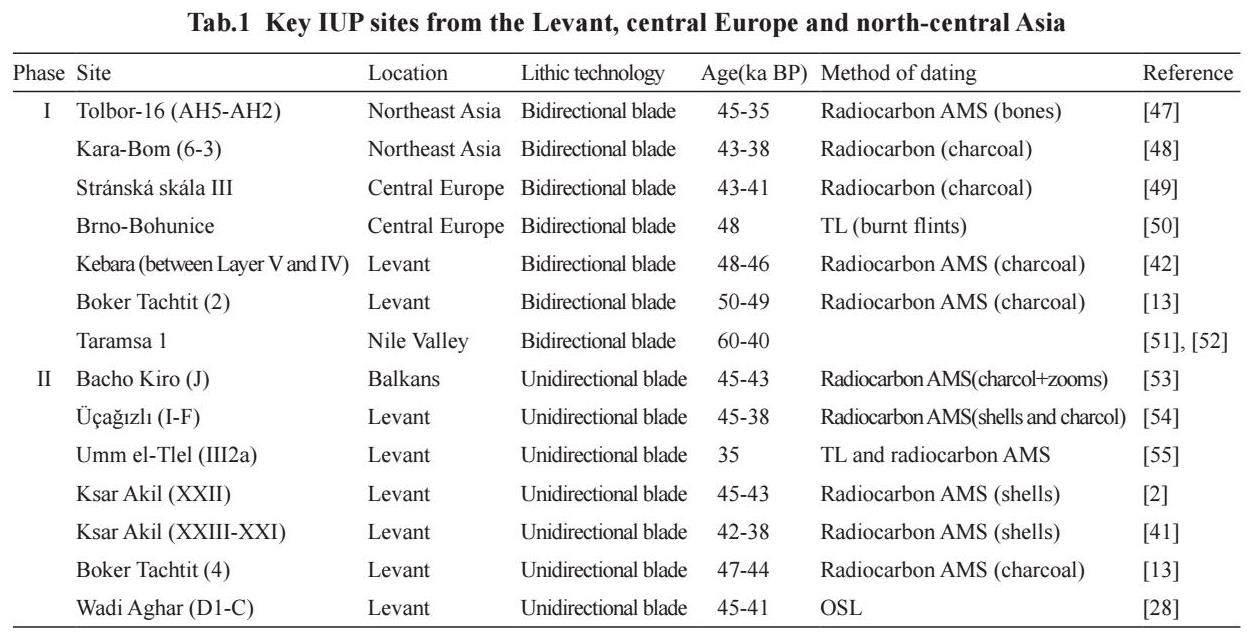

The absolute chronology of the Levantine IUP is a debated topic that bear implications onthe study of human migrations[2, 13, 40-42]. Absolute dating was conducted independently at severalintermediate sites by different methods and protocols[2, 13, 28, 41, 42, 43-51](Tab.1). Not surprisingly theresults provided a wide range of time from as early as 47 ka to ca. 34 ka[2, 13, 41].

There are two approaches to the Levantine IUP timeline, a lower and upper chronology. Thelower chronology, based upon the old dating of Boker Tachtit level 1[25], propose the beginning ofthe UP at 47 ka. For many years, this value was accepted as the startup age for the colonizationof Europe by modern humans, a process that presumably lasted 7000 years[52]. The lowerchronology was supported by a recent study at Kebara Cave which dated charcoals from MP andUP layers using two preparation protocols, ABA and ABOx[42]. While no IUP layer was evidentin the sampled stratigraphic section at Kebara, the time range for this phase was proposed at 48-46 ka based on dates from the MP layer below and the early UP layer above.

In 2013, Douka et al proposed an upper chronology for the IUP based on new dating ofshell beads from the Ksar Akil collection. Their suggestion was that the IUP began at 42 ka basedon dates from Ksar Akil and ??a??zl? Cave. Considering the results, the dates of Kebara and theone date from Boker Tachtit level 1 were thought to be too old[53].

A more recent dating project from Ksar Akil by Bosch et al[2]. demonstrated the problematicdating of shells from old collections as the new dates from the same levels were now ca.3000 years older, setting the beginning of the IUP in the northern Levant to 45 ka. A possibleexplanation for the disagreement in ages is the usage of differing sample selection and modelparameters. Still, a more plausible explanation is contamination and/or mislabeled samples whichwere excavated in the 1930s and 40s[19, 54]. The definitions and documentation of contexts from which the shells were collected does not meet current standards (i.e., site formation processes,microstratigraphy, retrieval of small components etc.).

In 2017, Alex et al radiocarbon dated the Early Upper Paleolithic sequence at ManotCave[40]. The new study refuted the Douka et al chronology for the Early Upper PaleolithicAhmarian techno-complex[41] and supported that of Bosch et al[2]. Accordingly, we adopt here thelower chronology proposed for Ksar Akil by Bosch et al[2].

The most recent and updated dating project is the new chronology of Boker Tachtit whichrelies on radiocarbon and OSL methods[13, 55]. The new study set the age of the IUP at Boker Tachtitto 50-44 ka. The early phase, the Emiran (Level 2 in the new study) began as early as 50 ka. Thelater phase, Level 4, start at 47 ka and ended at 44 ka. These results provide high-resolution forthe two phases at one site, providing a successive chrono-cultural sequence for the Levantine IUP.

One of the major contributions of the new dating project at Boker Tachtit was therecognition of contemporaneous radiocarbon ages from the two levels Boker Tachtit with thefinal Late Middle Paleolithic (LMP) occupations at the neighboring sites of Farah II (westernNegev), Tor Faraj Layer C (southern Jordan), and the final stages of the LMP at Kebara Cave inMt. Carmel[13]. This overlapping clearly proved the Emiran was not a local industry.

4 The origins and destinations of the Levantine IUP

Tracing population movement in the archaeological record is not easy mainly due to a lackof human fossils and reliable absolute chronology. With the absence of human fossils, stone tooltechnologies are often considered as the most reliable indicators for specific populations[10,51]. Oneof the most widely acknowledged examples is the association of the Clovis culture (and the Clovispoint) with the colonization of North America[56]. In our case, we will refer to the diagnostic bladetechnology of the early and late phases of the Levantine IUP in an attempt to discern a spatial pattern.

Regarding chronology, until recently the dates of the IUP were insecure as was theinterpretation for its role in the out-of-Africa model. New dating projects in some key regionsenable us now to examine the IUP and human dispersal model[13, 44, 49].

5 The origins of the early phase, the Emiran

Two scenarios have been suggested for the origins of the Boker Tachtit industries: localdevelopment and off-regional origin African/Arabian. The local development scenario, proposedby Meignen[57], argues that IUP technical traits emerged from local LMP groups. This hypothesisis now refuted as the new dates from Boker Tachtit clearly show the co-existence of Emiran andLate Mousterian, thus implying that the origin of the Emiran industry is not in this region.

To test the off-regional origin of the Emiran industry we turn to the bordering regions fromthe south, the Nile Valley and Arabia.

The late Middle Paleolithic in the Lower Nile Valley is characterized by the so-called Taramsanindustry[48]. In his comparative study, Van Peer describes the lithic assemblage from Taramsa 1 asa transitional Levallois system adapted to producing blades[47]. This system shares common featureswith Emiran, as noted by Van Peer, with respect to the core orientation and the volumetric conceptwhich emphasized production of blade from two opposed striking platforms. The chronology of theTaramsan is not well established and is thought to range between 60-40 ka (Taramsa phases IV IV V).Nevertheless, the site of Taramsa 1 is considered a potential forbearer of the Emiran[48].

Another candidate of being the forerunner of the Emiran are the late MP sites of Shi'batDihya 1 and 2 in the southern Arabian Peninsula[58]. The sites, dated by OSL to 55 ka, showa clear orientation for blade technology in addition to Levallois. The blades were aimed atproducing elongated points from unidirectional cores.

Another proposition for the origins of the Emiran was made by Marks who suggested that itevolved from the Tabun D tradition[15]. Currently it is difficult to confirm this hypothesis since there areno LMP sites bearing Tabun D tradition. The potential site referred by Marks is Ain Difla in southernJordan. While the lithic assemblages from the site are clearly dominated by bidirectional bladetechnology, the current chronology of the sites, dated to 105 ka, indicating a gap of 50 ka between AinDifla and Boker Tachtit[59]. Recent work by Rezek[60] is attempting to refine the chronology of AinDifla. Interestingly it is suggested the lithic industry could be ascribed to the local IUP.

6 The destinations of the early phase- the Emiran

This existence of bidirectional blade technology is noted in some of the IUP sites in otherregions – specifically in central Europe and northeast Asia.

In central Europe it is noted in the Bohunician technocomplex. The work of ?krdla[61]demonstrated significant technological correspondence (except for bifacial points) between BokerTachtit, Negev Desert and the sites of Brno-Bohunice and Stránská skála, Czech Republic. The tworegions show also chronological similarities. The TL chronology of Brno-Bohunice (48 ka) indicate that the site is more or less contemporary with Boker Tachtit (50 ka). The radiocarbon from Stránskáskála are later (43-41 ka) indicating on local phases. Nevertheless, the chronological differencesbetween the early phase of the Emiran and the early phase of the Bohunician is ca. 2000 years, whichis the estimated time for an expansion from one region to another[13, 46].

Another site bearing similar lithic technology is Tolbor 16, Mongolia[44]. Technologicallythe site is characterized by bidirectional blade technology accompanied with bladelet productionfrom burin cores. These two methods were in use in the Levantine Emiran at the lower levels atBoker Tachtit. Radiocarbon chronologies suggest the Tolbor 16 region was inhabited as early as45 ka, ca. 5000 years after Boker Tachtit was initially settled.

7 The later expansion within IUP

Unidirectional blade technology dominated the upper phase of Boker Tachtit, dated to 47-44 ka.Notably, unidirectional blades dominate the IUP occupations at Ksar Akil and ??a??zl? cave. Thechronology of the northern Levantine site is slightly later at Boker Tachtit by 1000-2000 years[2].Since no Emiran (early phase) with bidirectional blades was recorded at Ksar Akil and ??a??zl? caveit is reasonable to assume these assemblages emanated from the Negev.

The recent dating project in the Balkans placed Bacho Kiro as the earliest IUP sitewith modern human remain at 45 ka[49]. The lithic technology at the site seem to follow theunidirectional concept; thus it is quite reasonable to assume the hominin population and theirlithic technology originated in the Levant.

8 The two-dispersal model

The new dating at the sites of Boker Tachtit, Ksar Akil, Tolbor 16 and Bacho Kirosuggests a more complex scenario for the MIS 3 dispersal of modern humans. According tothe lithic characteristics we know that there are two chronological phases at Boker Tachtit.When supplemented with absolute chronology we can observe two dispersal events. The first,the Emiran, characterized by the bidirectional blade technology, was likely initiated in the aridregions of the southern Levant at ca. 50 ka. The origins of this industry seem to be rooted in theTaramsan of the lower Nile Valley and possibly the late MP of southern Arabia which could havemet in the Negev Desert to form the Emiran (Fig.4).

The Emiran developed locally at Boker Tachtit into a later phase characterized byunidirectional blades. But at the same time, it kept moving northward to the northern Levantfrom where it split into two directions, westward towards central Europe and eastward towardsnortheast Asia. The process was fast and lasted no more than 5000 years.

A second dispersal wave began in the Negev from the upper level at Boker Tachtit,spreading locally in the southern Levant and to the northern Levant where it was well established.From there it probably spread to the Balkans, to Bacho Kiro which was the gateway to Europe. The later phase kept on evolving locally in the Levant into the Early Ahmarian whereas inEurope (Bacho Kiro) it evolved into the proto-Aurignacian.

9 Conclusions

Two lithic traditions were superimposed at the site of Boker Tachtit. The early one, theEmiran, was characterized by bidirectional blade technology whereas the later one featuredunidirectional blades.

The early tradition is not native as its lithic technology is different from the local contemporarylate MP sites in the southern Levant. Its origins might have been the lower Nile Valley and/or southern

Arabia. The Emiran established itself in the region ca. 50 ka and developed into the later phase butalso kept dispersing to the north, central Europe, and northeast Asia.

The later phase expanded to the northern Levant and to southern Europe 45 ka. In theLevant it developed to the local Ahmarian tradition.

Acknowledgements: Thanks are extended the following colleagues for their assistance: IsraelHershkovitz for reading an early draft of this manuscript; Samuel Wolf for editorial comments;Michal Birkenfeld for preparing Fig.1; Carmen Hersh for preparing Figures 2-4. All artifactimages in Figures 2-4 were photographed by Yael Yulevich and Clara Amit, and are courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

References

[1] Higham T, Douka K, Wood R, et al. The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance[J]. Nature, 2014, 512, 306–309

[2] Bosch MD, Mannino MA, Prendergast AL, et al. New chronology for Ks?r ‘Akil (Lebanon) supports Levantine route of modernhuman dispersal into Europe[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2015, 112(25): 7683–7688

[3] Hublin JJ. The modern human colonization of western Eurasia: when and where?[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2015, 118: 194-210

[4] Harvati K. Neanderthals-Evolution: Education and Outreach[J]. 2010, 3(3): 367-376

[5] Sankararaman S, Mallick S, Dannemann M, et al. The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans[J]. Nature,2014, 507(7492): 354-357

[6] Prüfer K, Racimo F, Patterson N. The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains[J]. Nature, 2014,505(7481): 43-49

[7] Bae C, Dauka K, Petraglia MD. On the origin of modern humans: Asian perspectives[J]. Science, 2017, 358: eaai9067

[8] Hershkovitz I, Marder O, Ayalon A, et al. Levantine cranium from Manot Cave (Israel) foreshadows the first European modernhumans[J]. Nature, 2015, 520(7546): 216-219

[9] Hershkovitz I, Weber GW, Quam R, et al. The earliest modern humans outside Africa[J]. Science, 2018, 359(6374): 456-459

[10] Bar-Yosef O, Belfer-Cohen A. Following Pleistocene road signs of human dispersals across Eurasia[J]. Quat. Int., 2013, 285: 30-43

[11] Groucut HG, Scerri EML, Lewis L, et al. Stone tool assemblages and models for the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa[J].Quat. Int., 2015, 382: 8-30

[12] Kuhn SL, Zwyns N. Rethinking the Initial Upper Paleolithic[J]. Quat. Int., 2014, 347: 29-38

[13] Boaretto E, Hernandez M, Goder-Goldberger M, et al. The absolute chronology of Boker Tachtit (Israel) and implications for theMiddle to Upper Paleolithic transition in the Levant[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2021, 118(25): e2014657118

[14] Marks AE, Ferring CR. The Early Upper Paleolithic of the Levant[A]. In: Hoffecker JF, Wolf CA (Eds.). The Early UpperPaleolithic: Evidence from Europe and the Near East[M]. Oxford: BAR International Series 437, 1988, 43-72

[15] Marks AE, Rose JI. A century of research into the origins of the Upper Paleolithic in the Levant[A]. In: Otte M (Ed.). Néandertal/Cro-Magnon. La Rencontre[M]. Arles: Editions Errance, 2014, 221-266

[16] Turville-Petre FAJ. Researches in prehistoric Galilee, 1925-1926: British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem[M]. London:Chiswick Press, 1927

[17] Garrod DA. A transitional industry from the base of the Upper Palaeolithic in Palestine and Syria[J]. Journal of the AnthropologicalInstitute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1951, 81:121-130

[18] Haller JEAN. Notes de préhistoire phénicienne: LAbri de Abou-Halka (Tripoli)[M]. Beyrouth: Bulletin de Musée, 1946, 6: 1-20

[19] Ewing JF. Preliminary note on the excavations at the Palaeolithic site of Ksar Akil, Republic of Lebanon[J]. Antiquity, 1947, 21(84): 186

[20] Barzilai O, Gubenko N. Rethinking Emireh Cave: the lithic technology perspectives[J]. Quat. Int., 2018, 464: 92-105

[21] Copeland L. The Middle and Upper Paleolithic of Lebanon and Syria in the light of recent research[A]. In: Wendorf F, Marks A(Eds.). Problems in Prehistory: North Africa and the Levant[M]. Dallas: SMU Press. 1975, 317-350

[22] Gilead I. The upper Paleolithic period in the Levant[J]. Journal of World Prehistory, 1991, 5(2): 105-154

[23] Binford SR. Me'arat Shovakh (Mugharet esh-Shubbabiq). Israel Exploration Journal, 1966, 16(1): 18-32

[24] Schick T, Stekelis M. Mousterian assemblages in Kebara Cave, Mount Carmel[J]. Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical andGeographical Studies, 1977, 97-149

[25] Marks AE. Prehistory and Paleoenvironments in the Central Negev, Israel: the Avdat/Aqev Area (Vol. 3)[M]. Dallas: SMU Press. 1983

[26] Volkman P. Boker Tachtit: core reconstructions[A]. In: Marks A (Ed.). Prehistory and Paleoenvironments in the Central Negev,Israel[M]. Dallas: SMU Press. 1983, 127-190

[27] Fox J. The Tor Sadaf lithic assemblages: a technological study of the Early Upper Palaeolithic in the Wadi al-Hasa[A]. In: Goring-Morris AN, Belfer-Cohen A (Eds.). More than Meets the Eye: Studies on Upper Palaeolithic Diversity in the Near East[M]. Oxford:Oxbow Books. 2003, 80-94

[28] Kadowaki S, Tamura T, Sano K, et al. Lithic technology, chronology, and marine shells from Wadi Aghar, southern Jordan, andInitial Upper Paleolithic behaviors in the southern inland Levant[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2019, 135: 102646

[29] Kadowaki S, Suga E, Henry DO. Frequency and production technology of bladelets in Late Middle Paleolithic, Initial UpperPaleolithic, and Early Upper Paleolithic (Ahmarian) assemblages in Jebel Qalkha, Southern Jordan[J]. Quat. Int., 2021, 596, 4-21

[30] Demidenko YE, ?krdla P, Rychta?íková T. Initial Upper Paleolithic Bladelet Production: Bladelets in Moravian Bohunician[J].Recherches Archeologiques, 2020, 61(1): 21-29

[31] Azoury I. Ksar Akil, Lebanon: A technological and typological analysis of the transitional and early upper Palaeolithic levels ofKsar Akil and Abu Halka[M]. Oxford: BAR International Series 289 (i) and 289 (ii), 1986

[32] Ohnuma K. Ksar Akil, Lebanon, a Technological Study of the Earlier Upper Palaeolithic Levels at ‘Ksar Akil, Volume III. LevelsXXV-XIV[M]. Oxford: BAR International Series 426, 1988

[33] Copeland L. Forty-six Emireh points from the Lebanon in the context of the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition in the Levant[J].Paléorient, 2000, 26(1):73-92

[34] Leder D. Lithic variability and techno-economy of the initial Upper Palaeolithic in the Levant[J]. International Journal ofArchaeology, 2018, 6(1): 23-36

[35] Marks A. The Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition in the Southern Levant: Technological change as an adaptation to increasingmobility[A]. In: Otte M (Ed.). LHomme de Néandertal. Vol. 8: La Mutation[C]. Liège: Univ. de Liège. 1988, 109–124

[36] Newcomer MH. The chamfered pieces from Ksar Akil (Lebanon)[J]. Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology, 1970, 8(9): 177-191

[37] Kuhn SL, Stiner MC, Güle? E. Initial Upper Palaeolithic in south-central Turkey and its regional context: a preliminary report[J].Antiquity, 1999, 73: 505-517

[38] Kuhn SL, Stiner MC, Güle? E, et al. The early Upper Paleolithic occupations at ??a?izli Cave (Hatay, Turkey)[J]. Journal ofHuman Evolution, 2009, 56(2): 87–113

[39] Bo?da ?, Bonilauri S. The intermediate Paleolithic: the first bladelet production 40,000 years ago[J]. Anthropologie, 2006, 44(1): 75-92

[40] Alex B, Barzilai O, Hershkovitz I, et al. Radiocarbon chronology of Manot Cave, Israel and Upper Paleolithic dispersals[J]. ScienceAdvances, 2017, 3: e1701450

[41] Douka K, Bergman CA, Hedges REM, et al. Chronology of Ksar Akil (Lebanon) and implications for the colonization of Europeby Anatomically Modern Humans[J]. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(9): e72931

[42] Rebollo NR, Weiner S, Brock F, et al. New radiocarbon dating of the transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic in KebaraCave, Israel[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(9): 2424–2433

[43] Zwyns N, Paine CH, Tsedendorj B, et al. The northern Route for Human dispersal in central and northeast Asia: new evidence fromthe site of Tolbor-16, Mongolia[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9(1): 1-10

[44] Vasil'ev SA, Kuzmin YV, Orlova LA, et al. Radiocarbon-based chronology of the Paleolithic in Siberia and its relevance to thepeopling of the New World[J]. Radiocarbon, 2002, 44(2): 503-530

[45] Tostevin GB, ?krdla P. New excavations at Bohunice and the question of the uniqueness of the type-site for the Bohunicianindustrial type[J]. Anthropologie, 2006, 44(1): 31-48

[46] Richter D, Tostevin G, ?krdla P. Bohunician technology and thermoluminescence dating of the type locality of Brno-Bohunice(Czech Republic)[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2008, 55(5): 871-885

[47] Van Peer P. The Nile corridor and the out-of-Africa model an examination of the archaeological record[J]. Current Anthropology,1998, 39: S115-S140

[48] Wurz S, Van Peer P. Out of Africa, the Nile Valley and the Northern route[J]. The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 2012, 67(196): 168-179

[49] Hublin JJ, Sirakov N, Aldeias V, et al. Initial Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens from Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria[J]. Nature, 2020, 581: 299–302

[50] Kadowaki S. Issues of chronological and geographical distributions of Middle and Upper Palaeolithic cultural variability in theLevant and implications for the learning behavior of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens[A]. In: Akazawa T, et al. (Eds). Dynamics ofLearning in Neanderthals and Modern Humans, Volume 1[C]. Tokyo: Springer, 2013: 59-91

[51] Haynes G, Gary H. The Early Settlement of North America: the Clovis Era[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002

[52] Mellars P. Archeology and the dispersal of modern humans in Europe: Deconstructing the “Aurignacian”[J]. EvolutionaryAnthropology, 2006, 15(5):167–182

[53] Douka K. Exploring “the great wilderness of prehistory”: the chronology of the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic Transition in theNorthern Levant[J]. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte, 2013, 22:11–40

[54] Williams JK, Bergman CA. Upper Paleolithic levels XIII-VI (A and B) from the 1937-1938 and 1947-1948 Boston collegeexcavations and the Levantine Aurignacian at Ksar Akil, Lebanon[J]. Paléorient, 2010, 36(2):117-161

[55] Barzilai O, Boaretto E. Boqer Tahtit (Boker Tachtit): Preliminary Report[J]. Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys inIsrael, 2016, 128-133

[56] Smallwood AM. Clovis technology and settlement in the American Southeast: Using biface analysis to evaluate dispersalmodels[J]. American Antiquity, 2012, 77(4): 689-713

[57] Meignen L. Levantine perspectives on the Middle to Upper Paleolithic “transition”[J]. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropologyof Eurasia, 2012, 40: 12-21

[58] Delagnes A, Tribolo C, Bertran P, et al. Inland human settlement in southern Arabia 55,000 years ago[J]. Journal of HumanEvolution, 2012, 63: 452-474

[59] Clark GA, Schuldenrein J, Donaldson ML, et al. Chronostratigraphic contexts of Middle Paleolithic horizons at the ‘Ain Difla rockshelter(WHS 634), west-central Jordan[A]. The prehistory of Jordan, II. Perspectives from 1997[M]. Berlin: ex oriente, 1997, 77-100

[60] Rezek Z. Ain Difla[A]. Archaeology in Jordan 2: 2018-2019[R]. Amman: ACOR Jordan, 2020, 134-135

[61] ?krdla P. Comparison of Boker Tachtit and Stránská skála MP/UP transitional industries[J]. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society,2003, 33: 37-73