小鼠肝癌治疗模型的研究进展*

2022-10-13高重庆周星言刘均立洪健

高重庆, 周星言, 刘均立, 洪健

小鼠肝癌治疗模型的研究进展*

高重庆, 周星言, 刘均立, 洪健△

(暨南大学基础医学与公共卫生学院,广东 广州 510630)

小鼠;肝细胞癌;动物模型;肝癌治疗

原发性肝癌(以下简称肝癌)是世界上常见的恶性肿瘤和肿瘤致死病因之一,其发病率和死亡率逐年上升,我国是肝癌高发区,发病人数占全球的半数以上[1]。由于肝癌侵袭性强,具有早期侵犯门静脉和肝静脉分支等特性,易发生肝内转移,疾病进展迅速,预后极差[2]。近年来,随着手术、微创介入、放疗等局部治疗和化疗、免疫、靶向等系统治疗方式不断完善,肝癌患者5年生存率逐渐提高,但是整体疗效仍欠佳[3]。小鼠肝癌模型在一定程度上模拟了肿瘤患者的体内微环境,为肝癌新药物的筛选提供良好的工具[4]。其中,小鼠肝癌治疗模型是在肝癌早期、进展期及术后进行干预或治疗,旨在对不同阶段肝癌进行防治,为肝癌的临床前药物评价体系和指导治疗提供重要的依据。本文结合目前国内外有关小鼠肝癌治疗模型的研究情况,作如下综述。

1 小鼠肝癌发生的早期干预模型

人类肝癌发生与肝炎病毒慢性感染、化学致癌物暴露及代谢功能紊乱等多种因素有关[5-6],其致癌机制是一个多步骤、多因素、多基因协同的复杂过程[7-8],涉及肝损伤、肝纤维化、肝硬化及肝癌等病理改变[9-10]。为较早对肝癌进行防治,该模型主要在肝癌发生的早期阶段进行人为干预,能较大程度地模拟人类肝癌发生发展过程,因而常被用于肝癌发生机制及早期干预的研究[11]。主要包括致癌物诱导、基因工程及非酒精性脂肪肝炎(non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, NASH)小鼠肝癌模型。

1.1致癌物诱导的小鼠肝癌模型化学致癌物诱导的小鼠肝癌模型的病理过程能较好地模拟肝损伤-肝炎-肝硬化-肝癌的演变进程,是肝癌研究中可行性高的治疗模型[12]。目前已知多种类型化学致癌物,根据作用机理分为遗传毒性和非遗传毒性两大类。遗传毒性致癌物可与DNA直接反应,在数百个位点破坏DNA,诱导DNA损伤而致癌,包括二乙基亚硝胺(diethylnitrosamine, DEN)[13]、四氯化碳(carbon tetrachloride, CCl4)[14]、黄曲霉毒素(aflatoxin, AFT)[15]和硫代乙酰胺(thioacetamide, TAA)[16]等;非遗传毒性致癌物不直接与DNA反应,而是通过控制细胞增殖、凋亡和分化从而诱导肿瘤发生,包括苯巴比妥(phenobarbital, PB)[17]和哌磺氯苯酸(tibric acid)等。

DEN是常用的遗传毒性致癌物,被肝脏中的酶如细胞色素P450代谢成甲醛、甲醇和烷基化中间产物后,直接损伤DNA诱发肝癌[18-19]。2周龄的C57BL/6J雄性小鼠腹腔注射DEN(2~5 mg/kg)平均40周后,80%~100%诱导成肝癌[20]。CCl4通过产生一系列细胞因子、趋化因子和促炎物质,引起Kupffer细胞产生炎性应答,在损伤、炎症和修复的过程中引发肝癌[21-23]。由于单独使用DEN造模时间较长,目前常将DEN与CCl4联合使用诱导肝癌,可缩短造模时间,降低小鼠死亡率,成模率高达100%[24]。

DEN与CCl4联合使用诱导的肝癌模型中,小鼠血清丙氨酸转氨酶、天冬氨酸转氨酶和甲胎蛋白(α-fetoprotein, AFP)水平明显上升,表明两者联合使用诱导的肝癌伴有肝细胞损伤和增生,具有与人体肝癌相似的病变过程[25-26]。此外,该模型诱导肝癌发生过程中检测到多种癌基因表达上调,应用抑制剂或敲除上调癌基因,减弱肝癌发生过程中的炎症反应和DNA损伤,降低肝癌发生率[27-29]。这种模型遵循了肝炎-纤维化-肝癌的自然演变过程,对模拟重复暴露于特定环境诱发的肿瘤具有重要的借鉴意义。

1.2转基因小鼠肝癌模型转基因小鼠肝癌模型是利用基因工程技术导入或敲除动物体内特定基因,影响动物性状表达并产生稳定遗传修饰的动物模型[30-31]。该模型在研究特殊基因在肝癌发生过程中的作用具有独特优势,为肝癌发病机制的探索、药物筛选和临床医学研究提供一种新的实验模型。根据修饰基因不同分为病毒基因、原癌基因、生长因子及肿瘤微环境等转基因模型。其中,HBV转基因小鼠模型是目前应用较多的肝癌模型之一。

基因是目前构建HBV转基因小鼠肝癌模型时采用较多的基因,作为HBV编码的病毒反式激活因子,能够控制转录过程、调节其它病毒基因表达[32]。已有研究证实基因的单独表达能通过影响宿主的生物合成,干扰基因的表达和细胞分化,诱发小鼠肝癌。分析结果显示HBV DNA序列在肝、肾组织中选择性高表达,与HBV感染者情况相同。4月龄时转基因小鼠肝细胞发生异常改变,并伴有HBx蛋白的高水平表达;8~10月龄时,肝脏出现似腺瘤的肿瘤结节,其内肝细胞HBx蛋白表达水平进一步升高,同时甲胎蛋白检测呈阳性[33]。

1.3细胞谱系示踪小鼠肝癌模型细胞谱系示踪技术是指利用细胞特异的标志物对某类细胞进行标记,并对该细胞后代的增殖、分化以及迁移等活动进行追踪观察,在揭示复杂多样生物学过程中的具体分子机制中发挥关键作用[34]。目前基于Cre-loxP系统和CRISPR-Cas9基因编辑技术建立的细胞谱系示踪小鼠肝癌模型,是最常用的用于研究肝癌细胞起源与转化的小鼠模型。

Cre-loxP介导的谱系示踪是目前广泛使用的体内追踪细胞命运转化的技术。通过在目的细胞中表达Cre重组酶进而去除插入到小鼠loxP侧翼的转录终止结构,可以使随后的报告基因表达,达到标记并敲除特定基因的效果。将Cre片段插入肝脏特异性表达的白蛋白(albumin,)启动子之后,构建肝细胞特异性启动Albumin-Cre小鼠。利用该小鼠与基因或功能域的loxP小鼠杂交,获得了肝细胞特异性基因或域敲除的小鼠,该模型中敲除引起肝细胞中NF-κB过度激活,促进肝细胞癌进展[35]。

CRISPR/Cas9可以在基因组特定位置快速准确的将大片段癌基因敲入小鼠的DNA中,建立体细胞基因编辑小鼠模型。该模型打破小鼠遗传品系限制,实现不同遗传背景或在已有基因修饰小鼠模型基础上的基因编辑,缩短造模周期,降低造成本。基于CRISPR/Cas9系统在小鼠体内敲入癌基因同时敲除抑癌基因,1个月后小鼠肝脏中形成肿瘤[36]。

1.4NASH小鼠肝癌模型非酒精性脂肪性肝病(non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD)是指除酒精和其他明确的肝损伤因素外所致的,以弥漫性肝细胞大泡性脂肪变为主要特征的慢性肝脏疾病[37]。在NAFLD患者中,约10%~30%会发展成更为严重的NASH,最终导致肝硬化甚至肝细胞癌[38]。随着生活水平的提高和饮食结构的改变,NASH患病率逐年升高,且尚无有效治疗手段。因此,建立一个可靠的NASH动物模型对推进NASH发病机制的研究以及进行药物筛选意义重大。目前,较为常用的动物模型有蛋氨酸及胆碱缺乏(methionine- and choline-deficient, MCD)饮食和高脂饮食(high-fat diet, HFD)诱导的小鼠NASH模型[39-40],但这两种模型均不能较好模拟临床NASH病人的诸多病理特征,存在较明显缺陷。2018年首次报道的西方饮食(western diet, WD)+CCl4诱导的NASH模型,与人类NASH基因谱表达高度相似,且优于原有模型,故近几年成为主流NASH模型[41]。

通过高脂肪、高果糖和高胆固醇的西方饮食,结合每周腹腔内注射的低剂量CCl4作为加速剂,建立肝脏广泛纤维化和肿瘤快速进展的NASH小鼠肝癌模型,12周内出现人类NASH的所有代谢和组织学特征,24周时发展为肝癌[42]。该模型概述了脂肪肝从单纯脂肪变性到炎症、纤维化及肝癌不同阶段的病理改变,与人类病变过程高度相似,且其简易性和可重复性使其成为研究NASH肝癌发病机制和研发新治疗方法的有效模型。

2 小鼠进展期肝癌治疗模型

常见的肝癌进程分为肝硬化、癌前期、早期和进展期四个阶段[43]。肝癌起病隐匿、发展迅速,多数患者就诊时已处于进展期阶段。随着甲苯磺酸索拉非尼的问世,进展期肝癌的治疗取得了一定程度的进展,但由于药物耐药和患者耐受等原因,疗效仍欠佳[44]。小鼠肝癌进展期的治疗模型充分模拟肿瘤体内进展过程,维持了原有瘤组织的结构和绝大部分生物学特性,目前,常将人源肿瘤细胞或组织移植到免疫缺陷小鼠体内,使肿瘤细胞或组织在宿主体内以类似于患者体内的方式显示其恶性特征。根据移植物来源不同,分为人源肿瘤细胞系异种移植(cell-derived xenograft, CDX)和人源肿瘤组织异种移植(patient-derived xenograft, PDX),移植部位有异位移植与原位移植[45-46]。小鼠肝癌进展期治疗模型是在肿瘤进展阶段进行人为干预治疗,用于研究不同治疗方式对肝癌进展的影响。

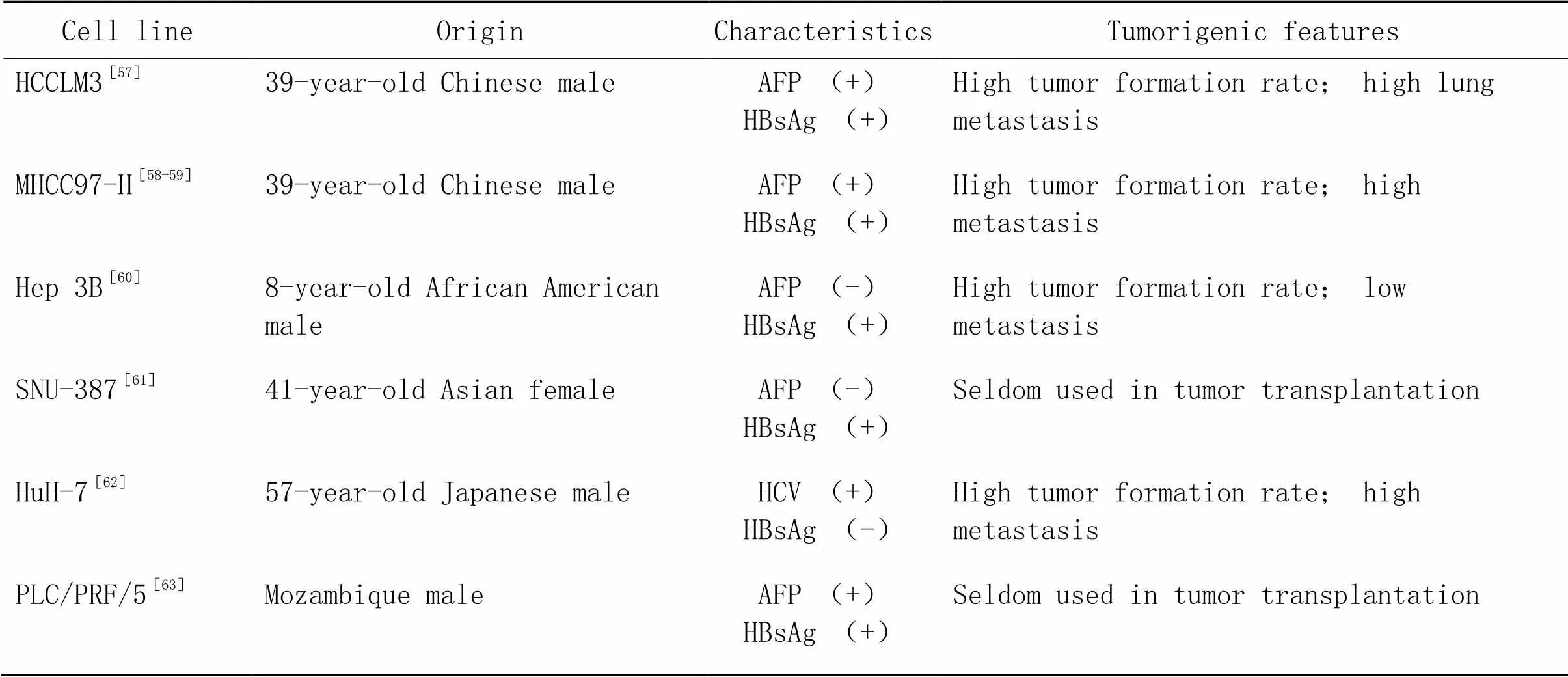

2.1CDX小鼠肝癌模型CDX小鼠肝癌模型是指将人源肿瘤细胞经体外传代培养获得稳定细胞系,通过皮下、原位、腹腔移植或尾静脉注射的方式接种到免疫缺陷小鼠体内,形成皮下、原位和转移瘤模型[47]。CDX模型具有实验周期短、建模成功率高、实验费用低等优点,作为抗肿瘤药物筛选模型已得到广泛应用[48-49]。CDX小鼠肝癌模型根据移植部位不同可分为皮下移植瘤模型、原位移植瘤模型和转移瘤模型[50-51]。其中,不同肝癌细胞系成瘤特点不同(表1)。提高成瘤率(1)选取成瘤率较高的细胞系;(2)增大细胞悬液浓度;(3)若成瘤率仍较低,将已成瘤鼠的瘤块取出接种至新鼠体内,成瘤后再取出接种新鼠,如此传2~3代,待肿瘤性质稳定后,再将肿瘤取出,剪碎、研磨、匀浆成为细胞悬液后再接种。

表1 人肝癌细胞系小鼠移植瘤的成瘤比较

2.1.1CDX皮下移植瘤模型CDX皮下移植瘤模型是将人源肝癌细胞移植到免疫缺陷小鼠皮下,观察肿瘤的形成、发展及抗肿瘤药物疗效的模型[52]。皮下移植操作简便、易于观察、成功率高。主要操作步骤:将(1~5)×106对数生长期的人源肝癌细胞悬浮于0.1~0.2 mL无血清培养液或PBS中,接种于裸鼠皮下血管丰富且易操作的部位,如腋下、腹股沟、侧腹部或颈背部等,其中腋下中部皮下成瘤率高。1周左右可在注射部位触及2~3 mm3皮下瘤肿块,并用游标卡尺定期测量肿瘤尺寸。

2.1.2CDX原位移植瘤模型CDX原位移植瘤模型是将人源肝癌细胞移植到免疫缺陷小鼠肝脏左外叶被膜下的小鼠肝癌模型[53]。接种等量肿瘤细胞,不同组小鼠初始瘤负荷相同,肿瘤的大小和位置较易控制,个体差异较小,接种成活率高。但因涉及小鼠的麻醉、开关腹等手术过程,操作相对复杂[54]。主要操作步骤:将(1~5)×106对数生长期的人源肝癌细胞悬浮于10~20 μL含有50%高浓度基质胶的无血清培养液或PBS中,直接注射到小鼠的肝左外叶被膜下,约1周后形成肝肿瘤。

2.1.3CDX转移瘤模型肿瘤转移是肝癌致死的首要原因,其过程包括:原位侵袭、肿瘤细胞内渗并存活于循环系统、肿瘤细胞外渗形成转移灶等。肿瘤细胞的器官转移往往有其偏好的器官,如肝、肺、骨和淋巴结等[55]。用生物发光活体成像技术监测肿瘤生长及后期的转移情况可以初步判断肿瘤细胞的转移能力。肝癌转移模型能够模拟体内肿瘤转移过程,有助于对肿瘤转移机制的研究及抗肝癌转移药物药效的评估[56]。根据移植部位不同分为腹腔移植转移瘤模型和尾静脉注射转移瘤模型。

腹腔移植转移瘤模型是将人源肝癌细胞注入免疫缺陷小鼠腹腔内,操作简单,可局部侵袭肠、胰腺、肾和肌肉组织等,部分发生肝内或肺转移,但移植瘤位置较深,不利于观察和测量。主要操作步骤:取(1~5)×106对数生长期的人源肝癌细胞悬浮于10~20 μL无血清培养液或PBS中,直接注射到裸鼠右下腹腔内,移植成功率可达100%。

尾静脉转移瘤模型是将人源肝癌细胞经小鼠尾静脉注入免疫缺陷小鼠体内,通过肺部的毛细血管网进入动脉血液循环系统,由于肿瘤细胞粘稠阻塞小鼠肺部微血管,主要造成肺转移,后期可能发生远处器官的转移。主要操作步骤:取(1~5)×106对数生长期的人源肝癌细胞悬浮于10~20 μL无血清培养液或PBS中,经尾静脉注入小鼠体内,肺转移率可达100%。

2.2PDX小鼠肝癌模型PDX小鼠肝癌模型是将手术或穿刺获得的新鲜肿瘤组织经过处理后直接植入免疫缺陷小鼠体内建立的个体化肿瘤模型,高度保留了原始患者肿瘤基质组成部分,拥有更“自然”的肿瘤微环境,可维持亲代肿瘤的遗传特征并模拟生长、侵袭和转移在内的多种生物学行为[64]。该模型帮助科研人员研究肿瘤异质性和遗传复杂性,深入探索肿瘤的发生机制及潜在治疗靶点。PDX模型对治疗的反应与原发肿瘤高度相似,能够相对准确地反映体内情况,在筛选药物敏感性、耐药标记物及预测患者对治疗药物的反应(包括疗效、毒副作用、吸收程度等)等方面具有极大优势,因此被广泛应用于抗肿瘤药物的研发中[65-66]。与传统的CDX模型相比,PDX模型对治疗方法临床应用潜力的评估更加精确[67]。临床前研究中,利用CDX模型进行药物筛选与临床相关性不到5%;应用PDX模型后,其相关性高达90%[68]。临床应用中,手术后患者对放化疗及靶向治疗的选择存在很多随机性与盲目性,应用指南一线药物之后,对二、三线药物的选择更具有随机性,此时利用PDX模型可为患者筛选出更有效的药物,设计个体化治疗方案[69]。

肿瘤组织来源于患者手术或活检标本,不可重复获取,PDX模型可将少量珍贵的临床样本快速扩大,且第一代所得样本可直接用于下一代建模。但随着传代次数增加,原始肿瘤组织中只有适应体外培养条件的单个克隆得以保留,因而丧失了克隆异质性,肿瘤微环境逐渐被细胞外基质取代,因此对传代次数有一定限制[70]。根据移植部位不同可分为PDX皮下移植瘤模型和原位移植瘤模型。

PDX与CDX皮下和原位移植瘤模型移植方法相同,其主要不同点在于PDX模型需要用穿刺针将制备好的标本接种到上述部位[71]。标本取材制备取新鲜肿瘤组织放入4 ℃含5%双抗(青霉素和链霉素)的RPMI-1640无菌培养液中,去除结缔组织和坏死组织后剪成约1 mm×1 mm×1 mm的肿瘤块移植物,置于4 ℃环境的上述培养液中暂存,并在标本离体后2 h内完成移植。

2.3免疫系统人源化小鼠模型免疫系统紊乱会导致人类肿瘤的发生[72]。肿瘤的免疫治疗主要通过激活机体抗肿瘤免疫反应或阻断肿瘤免疫逃逸来清除体内的癌细胞,是继手术、放化疗、分子靶向之后的一种新的提高患者生存期的治疗方法[73-74]。肝癌免疫系统人源化小鼠模型是将人的造血细胞、淋巴细胞或组织植入免疫缺陷小鼠体内,在小鼠身上重建人类免疫系统,然后再将人源肝癌细胞或组织移植至小鼠体内构建的一种新的小鼠模型。该模型模拟人体肿瘤细胞与免疫系统之间的相互作用,在肿瘤免疫治疗药物研发和临床前评估中具有重要的应用前景。根据免疫系统重建的方法,模型主要分为三类:Hu-PBL(humanized peripheral blood mononuclear cells)、Hu-HSCs(humanized hematopoietic stem cells)和Hu-BLT(humanized bone marrow, liver, thymus)小鼠模型。

Hu-HSCs小鼠模型的造血系统及免疫细胞是造血干细胞在小鼠体内重新发育而来,对小鼠宿主具有免疫耐受,不会发生致死性移植物抗宿主反应,常被用于肝癌免疫系统人源化小鼠模型的构建。构建方式[75]:首先将免疫缺陷小鼠经亚致死剂量辐照处理,然后将1×105CD34+HSC(来源于人粒细胞集落刺激因子G-CFS动员的血液、骨髓、脐带血或胎儿肝)在24 h内经骨髓腔或尾静脉注射入小鼠体内,8周后将人源肝癌细胞或组织移植至小鼠体内(方法同上文CDX/PDX小鼠肝癌模型)。

3 小鼠肝癌术后复发治疗模型

肝癌外科治疗是患者获得长期生存的重要手段,但肝癌患者行根治性手术后 5 年复发率高达 50%~70%,降低术后复发率是提高肝癌整体疗效的关键[76]。肝癌术后复发往往与术前已经存在的微小播散灶和(或)肝癌多中心发生有关,导致肝癌术后复发的机制可能包括以下几个方面[77]:(1)肝脏病灶切除过程中,因挤压、搬动肝脏造成肿瘤破裂,使肿瘤细胞残留并转为休眠状态;(2)肝再生创造适合肿瘤生长的微环境,促进更多的血管生成物质及细胞因子进入血管,激活休眠状态的微小病灶[78-79];(3)肝再生激活肝细胞增殖的信号通路,促进肿瘤生长。现阶段尚无全球公认的肝癌术后辅助治疗方案[80]。对于合并高危复发因素的患者,往往积极采取干预措施,包括抗病毒、动脉介入、系统化疗、分子靶向及中医药治疗等,但是除了抗病毒药物治疗之外,其他治疗尚缺乏强有力的循证医学证据充分支持[81]。因此,目前提倡多学科合作及个体化的综合治疗,而基于遗传信息的精准治疗是未来的发展方向。

小鼠肝癌术后复发的治疗模型可模拟患者术后肿瘤的复发转移,为抗肝癌药物的研发提供更加有效的治疗模型[82],为肝癌的精准治疗提供强有力的临床前证据。具体操作步骤:在原位移植模型的基础上,再次开腹,观察肝脏、腹腔无肿瘤转移后,将已成瘤的小鼠肝脏行根治性手术切除,充分止血后逐层关闭腹腔[83]。随后观察肿瘤复发情况,可结合生物发光活体成像技术追踪肿瘤复发及再次转移情况。

4 总结与展望

小鼠肝癌模型能准确反映肝癌的生物学特性,模拟肝癌在人体内自然生长、侵袭及转移的全部过程;小鼠肝癌治疗模型作为小鼠肝癌模型的主要组成部分,为肝癌的基础与临床研究提供有力依据。科学有效的的治疗模型应与人类大多数肝癌病理组织类型相一致,具有合适的肿瘤体积、生长速度和存活时间,能反映肝癌的生物学特性,模拟人体的肿瘤微环境,方法操作简便,成功率高,重复性好。但不同模型有其优缺点,应根据不同研究目的合理选择。小鼠肝癌发生的早期干预模型模拟肝癌的发生过程,有利于进行肝癌早期干预的研究;小鼠肝癌进展期治疗模型模拟肝癌发生后的疾病进展过程,有利于研究不同干预方式对肝癌进展阶段的治疗效果;小鼠肝癌根治术后复发治疗模型模拟了患者术后肿瘤的复发与转移,有利于研究不同抗癌药物根治术后的辅助治疗效果。目前,肝癌的治疗是在多学科合作和个体化综合治疗基础上联合分子靶向药物,实现肿瘤的精准治疗,小鼠肝癌治疗模型是筛选抗肝癌药物的良好实验工具,期待未来开发出更多治疗模型,为肝癌的精准治疗提供可靠依据。

[1] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3):209-249.

[2] Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2021, 7(1):6-9.

[3] Wei W, Zeng H, Zheng R, et al. Cancer registration in china and its role in cancer prevention and control[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2020, 21(7):342-349.

[4] Zhao Y, Shuen TWH, Toh TB, et al. Development of a new patient-derived xenograft humanised mouse model to study human-specific tumour microenvironment and immunotherapy[J]. Gut, 2018, 67(10):1845-1854.

[5] Fujiwara N, Friedman SL, Goossens N, et al. Risk factors and prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of precision medicine[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 68(3):526-549.

[6] Fedeles BI, Essigmann JM. Impact of DNA lesion repair, replication and formation on the mutational spectra of environmental carcinogens: aflatoxin B1as a case study[J]. DNA Repair (Amst), 2018(11), 71:12-22.

[7] Jiang HY, Chen J, Xia CC, et al. Noninvasive imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma: from diagnosis to prognosis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2018, 24(22):2348-2362.

[8] Kulik L, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology and management of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Gastroenterology, 2019, 156(2):477-491.

[9] Mak LY, Wong DK, Pollicino T, et al. Occult hepatitis B infection and hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, virology, hepatocarcinogenesis and clinical significance[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 73(4):952-964.

[10] D'Souza S, Lau KC, Coffin CS, et al. Molecular mechanisms of viral hepatitis induced hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2020, 26(38):5759-5783.

[11] Mancarella S, Krol S, Crovace A, et al. Validation of hepatocellular carcinoma experimental models for TGF-β promoting tumor progression[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2019, 11(10):1510.

[12] Connor F, Rayner TF, Aitken SJ, et al. Mutational landscape of a chemically-induced mouse model of liver cancer[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 69(4):840-850.

[13] Esparza-Baquer A, Labiano I, Sharif O, et al. TREM-2 defends the liver against hepatocellular carcinoma through multifactorial protective mechanisms[J]. Gut, 2021, 70(7):1345-1361.

[14] Marrone AK, Shpyleva S, Chappell G, et al. Differentially expressed micrornas provide mechanistic insight into fibrosis-associated liver carcinogenesis in mice[J]. Mol Carcinog, 2016, 55(5):808-817.

[15] Fishbein A, Wang W, Yang H, et al. Resolution of eicosanoid/cytokine storm prevents carcinogen and inflammation-initiated hepatocellular cancer progression[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2020, 117(35):21576-21587.

[16] Nazmy EA, El-Khouly OA, Zaki MMA, et al. Targeting p53/TRAIL/caspase-8 signaling by adiponectin reverses thioacetamide-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in rats[J]. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2019, 72:103240.

[17] Kakehashi A, Ishii N, Okuno T, et al. Progression of hepatic adenoma to carcinoma inmutant mice induced by phenobarbital[J]. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2017, 2017:8541064.

[18] Memon A, Pyao Y, Jung Y, et al. A modified protocol of diethylnitrosamine administration in mice to model hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(15):5461.

[19] Tang Q, Wang Q, Zhang Q, et al. Gene expression, regulation of DEN and HBx induced HCC mice models and comparisons of tumor, para-tumor and normal tissues[J]. BMC Cancer, 2017, 17(1):862.

[20] Lei CJ, Wang B, Long ZX, et al. Investigation of PD-1H in DEN-induced mouse liver cancer model[J]. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2018, 22(16):5194-5199.

[21] Wang B, Chou YE, Lien MY, et al. Impacts of CCL4 gene polymorphisms on hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility and development[J]. Int J Med Sci, 2017, 14(9):880-884.

[22] Zheng D, Jiang Y, Qu C, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 tetramerization protects against hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis[J]. Am J Pathol, 2020, 190(11):2267-2281.

[23] Jiang Y, Chen P, Hu K, et al. Inflammatory microenvironment of fibrotic liver promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth, metastasis and sorafenib resistance through STAT3 activation[J]. J Cell Mol Med, 2021, 25(3):1568-1582.

[24] Qu C, Zheng D, Li S, et al. Tyrosine kinase SYK is a potential therapeutic target for liver fibrosis[J]. Hepatology, 2018, 68(3):1125-1139.

[25] Lin Y H, Zhang S, Zhu M, et al. Mice with increased numbers of polyploid hepatocytes maintain regenerative capacity but develop fewer hepatocellular carcinomas following chronic liver injury[J]. Gastroenterology, 2020, 158(6):1698-1712.

[26] Ma X, Qiu Y, Sun Y, et al. NOD2 inhibits tumorigenesis and increases chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting AMPK pathway[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2020, 11(3):174.

[27] Li J, Wang Q, Yang Y, et al. GSTZ1 deficiency promotes hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation via activation of the KEAP1/NRF2 pathway[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 38(1):438.

[28] Liu Y, Song L, Ni H, et al. ERBB4 acts as a suppressor in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2017, 38(4):465-473.

[29] Feng H, Liu J, Qiu Y, et al. RNA-binding motif protein 43 (RBM43) suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma progression through modulation of cyclin B1 expression[J]. Oncogene, 2020, 39(33):5495-5506.

[30] Sakurai T, Kamiyoshi A, Kawate H, et al. Production of genetically engineered mice with higher efficiency, lower mosaicism, and multiplexing capability using maternally expressed Cas9[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1):1091.

[31] Yin H, Xue W, Anderson DG. CRISPR-Cas: a tool for cancer research and therapeutics[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2019, 16(5):281-295.

[32] Levrero M, Zucman-Rossi J. Mechanisms of hbv-induced hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2016, 64(1):S84-S101.

[33] Kruse RL, Barzi M, Legras X, et al. A hepatitis b virus transgenic mouse model with a conditional, recombinant, episomal genome[J]. JHEP Rep, 2021, 3(2):100252-100259.

[34] Simeonov KP, Byrns CN, Clark ML, et al. Single-cell lineage tracing of metastatic cancer reveals selection of hybrid EMT states[J]. Cancer Cell, 2021, 39(8):1150-1162.

[35] Zhang W, Zhangyuan G, Wang F, et al. The zinc finger protein Miz1 suppresses liver tumorigenesis by restricting hepatocyte-driven macrophage activation and inflammation[J]. Immunity, 2021, 54(6):1168-1185.

[36] Mou H, Ozata DM, Smith JL, et al. CRISPR-SONIC: targeted somatic oncogene knock-in enables rapidcancer modeling[J]. Genome Med, 2019, 11(1):21.

[37] Anstee QM, Reeves HL, Kotsiliti E, et al. From nash to hcc: current concepts and future challenges[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, 16(7):411-428.

[38] Kucukoglu O, Sowa JP, Mazzolini GD, et al. Hepatokines and adipokines in nash-related hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2021, 74(2):442-457.

[39] 杨庆宇, 郜娜. 白藜芦醇通过miRNA-122调节神经酰胺水平而治疗非酒精性脂肪肝[J]. 中国病理生理杂志, 2017, 33(8):1506-1513.

Yang QY, Gao N. Effects of resveratrol on levels of ceramide via regulating miRNA-122 intreating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Chin J Pathophysiol, 2017, 33(8):1506-1513.

[40] Chyau CC, Wang HF, Zhang WJ, et al. Antrodan alleviates high-fat and high-fructose diet-induced fatty liver disease in C57BL/6 mice model via AMPK/SIRT1/SREBP-1c/PPARγ pathway[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(1):360.

[41] Tsuchida T, Lee YA, Fujiwara N, et al. A simple diet- and chemical-induced murine nash model with rapid progression of steatohepatitis, fibrosis and liver cancer[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 69(2):385-395.

[42] Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 380(15):1450-1462.

[43] Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10127):1301-1314.

[44] Tang W, Chen Z, Zhang W, et al. The mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: theoretical basis and therapeutic aspects[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2020, 5(1):87-97.

[45] Hu B, Li H, Guo W, et al. Establishment of a hepatocellular carcinoma patient-derived xenograft platform and its application in biomarker identification[J]. Int J Cancer, 2020, 146(6):1606-1617.

[46] Reiberger T, Chen Y, Ramjiawan RR, et al. An orthotopic mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma with underlying liver cirrhosis[J]. Nat Protoc, 2015, 10(8):1264-1274.

[47] He L, Tian DA, Li PY, et al. Mouse models of liver cancer: progress and recommendations[J]. Oncotarget, 2015, 6(27):23306-23322.

[48] Zhou Q, Tian W, Jiang Z, et al. A positive feedback loop of AKR1C3-mediated activation of NF-κB and STAT3 facilitates proliferation and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Cancer Res, 2021, 81(5):1361-1374.

[49] Zhou Y, Huan L, Wu Y, et al. LncRNA ID2-AS1 suppresses tumor metastasis by activating the HDAC8/ID2 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Cancer Lett, 2020, 469:399-409.

[50] Febbraio MA, Reibe S, Shalapour S, et al. Preclinical models for studying nash-driven hcc: how useful are they?[J]. Cell Metab, 2019, 29(1):18-26.

[51] Wu Y, Wang J, Zheng X, et al. Establishment and preclinical therapy of patient-derived hepatocellular carcinoma xenograft model[J]. Immunol Lett, 2020, 22(3):33-43.

[52] 王春玲, 张荣芳, 陈峰杰, 等. miR-509靶向Rac1调节人肝癌LM3细胞侵袭和迁移及裸鼠模型的存活[J]. 中国病理生理杂志, 2019, 35(5):813-818.

Wang CL, zhang RF, Chen FJ, et al. miR-509 regulates growth, invasion and migration of human hepatocellular carcinoma LM3 cells and survival of nude mice[J]. Chin J Pathophysiol, 2019, 35(5):813-818.

[53] Seyhoun I, Hajighasemlou S, Muhammadnejad S, et al. Combination therapy of sorafenib with mesenchymal stem cells as a novel cancer treatment regimen in xenograft models of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2019, 234(6):9495-9503.

[54] Jiang Y, Chen S, Li Q, et al. Tank-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) serves as a potential target for hepatocellular carcinoma by enhancing tumor immune infiltration[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12:612139.

[55] Tang TC, Man S, Lee CR, et al. Impact of metronomic uft/cyclophosphamide chemotherapy and antiangiogenic drug assessed in a new preclinical model of locally advanced orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Neoplasia, 2010, 12(3):264-274.

[56] Lv X, Yu H, Zhang Q, et al. SRXN1 stimulates hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis and metastasis through modulating ROS/p65/BTG2 signalling[J]. J Cell Mol Med, 2020, 24(18):10714-10729.

[57] Liao WW, Zhang C, Liu FR, et al. Effects of miR-155 on proliferation and apoptosis by regulating FoxO3a/BIM in liver cancer cell line HCCLM3[J]. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2020, 24(13):7196-7176.

[58] Li GC, Ye QH, Dong QZ, et al. TGF beta1 and related-Smads contribute to pulmonary metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma in mice model[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2012, 31(1):93.

[59] Li X, Hu J, Gu B, et al. Animal model of intrahepatic metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma: establishment and characteristic[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1):15199.

[60] Alessandri G, Pessina A, Paroni R, et al. Single-shot local injection of microfragmented fat tissue loaded with paclitaxel induces potent growth inhibition of hepatocellular carcinoma in nude mice[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2021, 13(21):5505-5512.

[61] López-Cánovas JL, Del Rio-Moreno M, García-Fernandez H, et al. Splicing factor SF3B1 is overexpressed and implicated in the aggressiveness and survival of hepatocellular carcinoma.[J]. Cancer Lett, 2021, 496:72-83.

[62] Mo SJ, Hou X, Hao XY, et al. EYA4 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma growth and invasion by suppressing NF-κB-dependent RAP1 transactivation[J]. Cancer Commun (Lond), 2018, 38(1):9-15.

[63] Guo X, Jiang H, Shi B, et al. Disruption of PD-1 enhanced the anti-tumor activity of chimeric antigen receptor T cells against hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2018, 9:1118.

[64] Ben-David U, Ha G, Tseng YY, et al. Patient-derived xenografts undergo mouse-specific tumor evolution[J]. Nat Genet, 2017, 49(11):1567-1575.

[65] Meehan TF. Know thy pdx model[J]. Cancer Res, 2019, 79(17):4324-4325.

[66] Okada S, Vaeteewoottacharn K, Kariya R. Application of highly immunocompromised mice for the establishment of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(8):889-899.

[67] Huang L, Bockorny B, Paul I, et al. Pdx-derived organoids modeldrug response and secrete biomarkers[J]. JCI Insight, 2020, 5(21):135544-135554.

[68] Xu W, Zhao ZY, An QM, et al. Comprehensive comparison of patient-derived xenograft models in hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic liver cancer[J]. Int J Med Sci, 2020, 17(18):3073-3081.

[69] Shi J, Li Y, Jia R, et al. The fidelity of cancer cells in pdx models: characteristics, mechanism and clinical significance[J]. Int J Cancer, 2020, 146(8):2078-2088.

[70] Jung J, Seol HS, Chang S. The generation and application of patient-derived xenograft model for cancer research[J]. Cancer Res Treat, 2018, 50(1):1-10.

[71] Meehan TF, Conte N, Goldstein T, et al. PDX-MI: minimal information for patient-derived tumor xenograft models[J]. Cancer Res, 2017, 77(21):e62-e66.

[72] Bruni D, Angell HK, Galon J, et al. The immune contexture and Immunoscore in cancer prognosis and therapeutic efficacy[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2020, 20(11):662-680.

[73] Walsh NC, Kenney LL, Jangalwe S, et al. Humanized mouse models of clinical disease[J]. Annu Rev Pathol, 2017, 24(12):187-215.

[74] Allen TM, Brehm MA, Bridges S, et al. Humanized immune system mouse models: progress, challenges and opportunities[J]. Nat Immunol, 2019, 20(7):770-774.

[75] Zhao Y, Shuen TWH, Toh TB, et al. Development of a new patient-derived xenograft humanised mouse model to study human-specific tumour microenvironment and immunotherapy[J]. Gut, 2018, 67(10):1845-1854.

[76] Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, et al. Aasld guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2018, 67(1):358-380.

[77] Lee KF, Chong CCN, Fong AKW, et al. Pattern of disease recurrence and its implications for postoperative surveillance after curative hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: experience from a single center[J]. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr, 2018, 7(5):320-330.

[78] Tabrizian P, Jibara G, Shrager B, et al. Recurrence of hepatocellular cancer after resection: patterns, treatments, and prognosis[J]. Ann Surg, 2015, 261(5):947-955.

[79] Xu X F, Xing H, Han J, et al. Risk factors, patterns, and outcomes of late recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter study from China[J]. JAMA Surg, 2019, 154(3):209-217.

[80] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 69(1):182-236.

[81] Wang Z, Ren Z, Chen Y, et al. Adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization for HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma after resection: a randomized controlled study[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2018, 24(9):2074-2081.

[82] Lauko A, Bayik D, Lathia JD. IL-11 drives postsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence[J]. EBioMedicine, 2019, 47:18-19.

[83] Wang D, Zheng X, Fu B, et al. Hepatectomy promotes recurrence of liver cancer by enhancing IL-11-STAT3 signaling[J]. EBioMedicine, 2019, 46:119-132.

Research progress in mouse treatment model of liver cancer

GAO Chong-qing, ZHOU Xing-yan, LIU Jun-li, HONG Jian△

(,,510632,)

Primary liver cancer is one of the most common aggressive malignancies worldwide. Due to the insidiousness of the onset of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and the lack of effective treatments, the prognosis of HCC patients is abysmal. The mouse liver cancer model is a common carrier for the study of primary liver cancer. The mouse treatment model of liver cancer is widely used in studies of the pathogenesis of primary liver cancer and screenings of new drugs. Among them, the induced and genetically engineered mouse liver cancer models simulate the whole process from liver injury to tumorigenesis, which are mainly used for the study of early intervention of tumors. The transplanted cell-derived xenograft (CDX) and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) mouse liver cancer models simulate the microenvironment of tumor cells growing, which are mainly used to study systemic therapy in the advanced stage of liver cancer. The postoperative recurrence model of mouse liver cancer mainly simulates the recurrence of tumors after resection in liver cancer patients and is mainly used to study postoperative adjuvant treatments. This article aims to introduce the principles, characteristics, modeling methods, and application of various mouse liver cancer models commonly used in anti-tumor therapy.

Mice; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Animal model; Treatment of liver cancer

1000-4718(2022)09-1686-08

2022-03-10

2022-05-19

13902280717; E-mail: hongjian7@jnu.edu.cn

R735.7; R363

A

10.3969/j.issn.1000-4718.2022.09.019

[基金项目]国家自然科学基金资助项目(No. 81871987);中央高校基本科研业务费专项资金资助(No. 21620106)

(责任编辑:宋延君,罗森)