Impact of referral pattern and timing of repair on surgical outcome after reconstruction of post-cholecystectomy bile duct injury: A multicenter study

2021-03-05AymnElNkeeAhmdSultnHelmyEzztMohmedAttiMohmedAdElWhThKyedAymnHssnenAhmdAlMlkiAhmedAlqrniMohmmedMohmmed

Aymn El Nkee Ahmd Sultn Helmy Ezzt Mohmed Atti Mohmed Ad ElWh Th Kyed Aymn Hssnen Ahmd AlMlki Ahmed Alqrni Mohmmed M Mohmmed

a Gastrointestinal Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

b Minia University Hospital, Minia, Egypt

c Aseer Central Hospital, Aseer region, Saudi Arabia

Keywords:Bile duct injury Hepaticojejunostomy Anastomotic stricture Biloma Biliary peritonitis

ABSTRACT Background: Bile duct injury (BDI) after cholecystectomy remains a significant surgical challenge. No guideline exists to guide the timing of repair, while few studies compare early versus late repair BDI.This study aimed to analyze the outcomes in patients undergoing immediate, intermediate, and delayed repair of BDI.Methods: We retrospectively analyzed 412 patients with BDI from March 2015 to January 2020. The patients were divided into three groups based on the time of BDI reconstruction. Group 1 underwent an immediate reconstruction (within the first 72 hours post-cholecystectomy, n = 156); group 2 underwent an intermediate reconstruction (from 4 days to 6 weeks post-cholecystectomy, n = 75), and group 3 underwent delayed reconstruction (after 6 weeks post-cholecystectomy, n = 181).Results: Patients in group 2 had significantly more early complications including anastomotic leakage and intra-abdominal collection and late complications including anastomotic stricture and secondary liver cirrhosis compared with groups 1 and 3. Favorable outcome was observed in 111 (71.2%) patients in group 1, 31 (41.3%) patients in group 2, and 157 (86.7%) patients in group 3 ( P = 0.0 0 01). Multivariate analysis identified that complete ligation of the bile duct, level E1 BDI and the use of external stent were independent factors of favorable outcome in group 1, the use of external stent was an independent factor of favorable outcome in group 2, and level E4 BDI was an independent factor of unfavorable outcome in group 3. Transected BDI and level E4 BDI were independent factors of unfavorable outcome.Conclusions: Favorable outcomes were more frequently observed in the immediate and delayed reconstruction of post-cholecystectomy BDI. Complete ligation of the bile duct, level E1 BDI and the use of external stent were independent factors of a favorable outcome.

Introduction

Complex BDI is often more common after LC. BDI is the most serious morbidity during cholecystectomy which has a significant effect on long-term survival and quality of life, and is linked with high rates of subsequent legal action [1 –5].

Early detection of BDI is necessary for the best possible treatment to be started. The management of patients with BDI is a challenge even for hepatobiliary surgeons [ 6 –9]. These patients should always be referred to a specialized center for proper management due to the difficulty of these injuries. The experience of the center and the surgeon is the most prominent factor for the outcome. Besides, timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment also play great roles in the management of this complex complication [2 –7].

A major factor affecting the timing of BDI reconstruction is that most BDIs are not diagnosed during the cholecystectomy and only present postoperatively, by which time the patient may be septic with infected bile collections, cholangitis, hypoalbuminemia, jaundice, with friable common bile duct (CBD) stump, and associated vascular injury [10 –15]. Both early and late reconstructions of major BDI are discussed. Some hepatobiliary surgeons advised delay surgical repair after controlling these septic conditions. Others advise early surgical repair and control of the sepsis at the same time for better patient quality of life and more favorable surgical outcomes compared with delayed repair [4 –7 , 12 –17].

The judgment for the timing of reconstruction in a patient equally suitable for early or delayed reconstruction should be depended on the predicted success of the operation, patient quality of life, and patient safety. No guidelines present to direct the timing of reconstruction, while few studies compare early versus late repair BDI. However, the timing of surgical repair of BDI is still an object of debate and no satisfactory study has yet been reported to inform this question [1 –5 , 14 –18].

This study aimed to present our experience in the management of post-cholecystectomy BDI and to analyze outcomes in patients undergoing immediate (within the first 72 hours post-cholecystectomy), intermediate (from 4 days to 6 weeks post-cholecystectomy) and delayed (after 6 weeks postcholecystectomy) reconstructions of BDI in three specialized centers.

Methods

Patients and characteristics

This was a retrospective multicentre study. All patients undergoing hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) reconstruction for management of post-cholecystectomy BDI between March 2015 and January 2020 in Gastrointestinal Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt,Minia University Hospital, Egypt, and Aseer Central Hospital, Aseer region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia were enrolled in the study. This included both patients who performed cholecystectomy at our centers and patients who underwent cholecystectomy at other hospitals and were later referred to our centers following the diagnosis of BDI. Exclusion criteria included patients with Child-Pugh C liver cirrhosis, patients with BDI due to trauma, patients with bile duct stricture due to chronic pancreatitis or tumor that required HJ, patients with multiple organ failure, contraindications for major abdominal surgery, and patients with minor BDI.

Patients’ data were recorded from prospectively maintained files for retrospective analysis. The records included preoperative variables, operative findings, and postoperative courses and followup. Written informed consent was routinely obtained from each patient after clearing up the character of injury after cholecystectomy, planned surgical methods and its morbidity and possible procedures and time of management. The protocol of this study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Patients were divided into three groups based on the timing of definitive biliary repair. Group 1: the immediate reconstruction of post-cholecystectomy BDI (within the first 72 hours post-cholecystectomy); group 2: the intermediate reconstruction of post-cholecystectomy BDI (from 4 days to 6 weeks postcholecystectomy); and group 3: delayed reconstruction of postcholecystectomy BDI (after 6 weeks post-cholecystectomy).

Preoperative assessment

Post-cholecystectomy BDI was suspected when the patient presented with post-cholecystectomy bile leakage, biloma, cholangitis,biliary peritonitis or obstructive jaundice during cholecystectomy or postoperation. Further assessments included abdominal ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography (CT) to assess the fluid collection and free fluid in the abdomen. A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was done to diagnose the level of BDI and the nature of the injury [19].

In patients with delayed post-cholecystectomy BDI undergoing HJ reconstruction, preoperative ultrasound tubal drainage was done in patients with biloma or free fluid in the abdomen until sepsis and inflammation were controlled and bile duct stump was dilated. Abdominal exploration was required for patients presented by biliary peritonitis (drains for the delayed reconstruction group or definite reconstruction for the immediate reconstruction group).The timing of reconstruction depended on the surgeons’ preference and pattern of presentation.

Operative details

Post-cholecystectomy BDI repair was done via Roux-en-Y HJ by specialized hepatobiliary surgeons at our centers. After the exploration of the abdomen, dissection and adhesiolysis were done to identify bile duct stump. Division of hilar plate was performed routinely in most of the cases to lengthen the bile duct stump. Limited hepatectomy or hepatotomy was needed in some cases. The common hepatic, left and right hepatic ducts were further mobilized based on the level of BDI until reaching healthy and vascular biliary stump. If there was no acceptable bleeding from the biliary stump, the dissection was continued up until reaching a healthy and vascular stump.

The sectorial bile ducts were approximated together if possible to enable the construction in a single or double jejunal anastomosis. The Roux-en-Y jejunal loop was prepared that transferred to the right abdominal cavity through the transverse mesocolon.Transanastomotic external stent through the jejunum (8–10 French Nelaton catheter, Shanghai, China) was placed in the immediate and intermediate reconstruction groups. HJ was performed by a single layer of Proline, Vicryl or PDS (3/0 or 4/0) sutures (interrupted, continuous, or both). HJ was performed as wide as possible, not under tension and good vascularity. HJ can be achieved as the end to side, side to side, or by the Hepp–Couinaud technique that tends to make a wide stoma by opening the anterior wall of the duct longitudinally and extending to the left hepatic duct as much as possible. Abdominal drains were placed in all patients.

Arterial reconstruction for associated hepatic artery injury was not required either in early or later repair because the injured hepatic arteries were already thrombosed. All early and late operations were done by the experienced hepatobiliary surgeons in three centers with the same principle.

Postoperative management

All patients were transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) immediately after operation before reassigned to the general ward.All patients received prophylactic antibiotics intraoperatively and continued postoperatively for 5 days. Vital signs, intravenous fluid,and drain outputs were followed up daily. Patients started oral fluids once bowel sounds were started.

Drainage tubes were removed and patients were discharged when tolerated the oral intake and routine laboratory follow-up and abdominal ultrasound revealed no abdominal collections. Patients with external stent were followed up and the stent was closed when liver function became normal, with no bile leakage nor abdominal collection. The stent was removed after 3 months following a cholangiogram.

Follow-up

Patients were followed up after 2 weeks, 3 months, 6 months,one year then annually. Each visit included a clinical examination,liver function tests, abdominal ultrasound to show the status of the liver. MRCP was done for patients presented by recurrent cholangitis to assess the patency of HJ.

Data collection

The database included the demographic data, injury based on the Strasberg classification, time of diagnosis, clinical presentation,comorbidity laboratory finding, time to referral, time of reconstruction and repair of BDI, blood loss, friability of tissue, operative time, use of stent, hospital stay, the total cost of hospitalization,final outcome, hospital mortality, and all postoperative morbidities according to the Clavien–Dindo classification [20]. The immediate morbidities included wound infection, bile leakage, biloma, liver failure, liver abscess, and biliary peritonitis. The late complications included anastomotic stricture that may need interventional dilatation or surgical reoperation, recurrent cholangitis, and liver cirrhosis.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was a favorable surgical outcome. The unfavorable outcome was the poor outcome with any late complications including anastomotic stricture, persistent hyperbilirubinemia, secondary liver cirrhosis, development of intraductal stone,liver failure, development of liver abscess, and reoperation.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes included operative time, blood loss,blood transfusion, use of external stent, hospital stay, early postoperative complications including bile leakage, blood loss, wound infection, liver failure, abdominal collection, early persistent hyperbilirubinemia, and mortality rate.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive data were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR) for continuous data and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Independent samplet-test or one-way ANOVA and Chi-square test were used as appropriate. AP<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Significant variables were analyzed by a logistic regression model to detect independent variables of favorable outcome of HJ reporting as odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Demographic data

The study included 412 consecutive patients who underwent HJ for post-cholecystectomy BDI between March 2015 and January 2020. Only 14 out of 11 600 cholecystectomies (0.12%) were injured in our centers (5/4140 in Gastrointestinal Surgical Center of Mansoura University, 4/3410 in Minia University Hospital, and 5/4050 in Aseer Hospital). The three centers are referral centers, and 398 BDIs were from peripheral hospitals. Gastrointestinal Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt is a referral hospital for Delta region in Egypt where has about 6 governments with a population of about 16 million, Minia University Hospital, Egypt, is a referral hospital for upper Egypt where has about 5 governments with a population of about 10 million and Aseer Central Hospital, Aseer region,Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a referral hospital for south Saudi with a population of about 5 million.

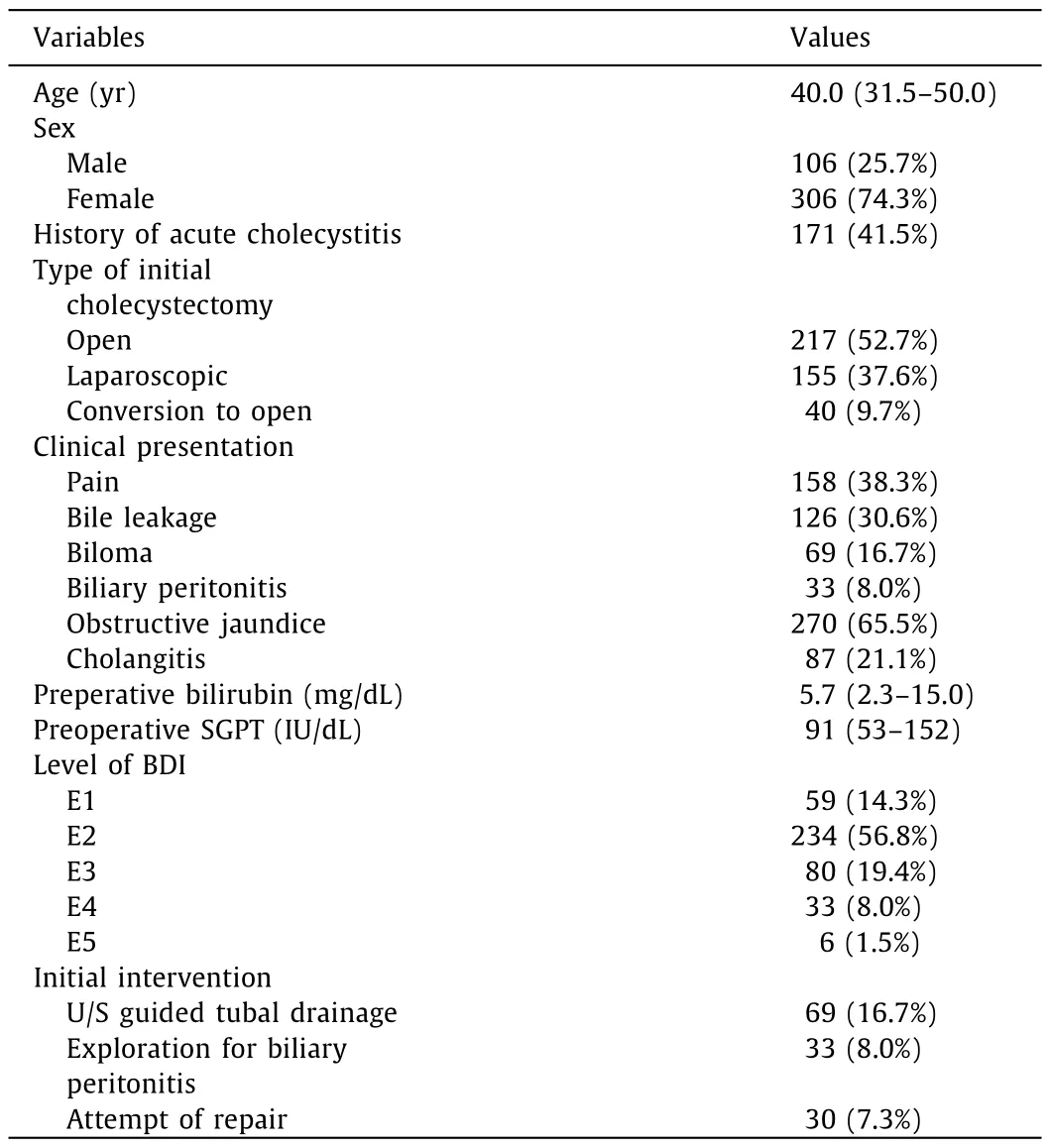

Table 1 Demographic data for patients with post-cholecystectomy bile duct injury.

The patients were divided into three groups based on the time of reconstruction. Group 1 included 156 (37.9%) patients who underwent immediate reconstruction of BDI within the first 72 hours of injury, group 2 included 75 (18.2%) patients who underwent intermediate reconstruction of BDI from 4 days to 6 weeks, and group 3 included 181 (43.9%) patients who underwent delayed repair of BDI after 6 weeks of injury.

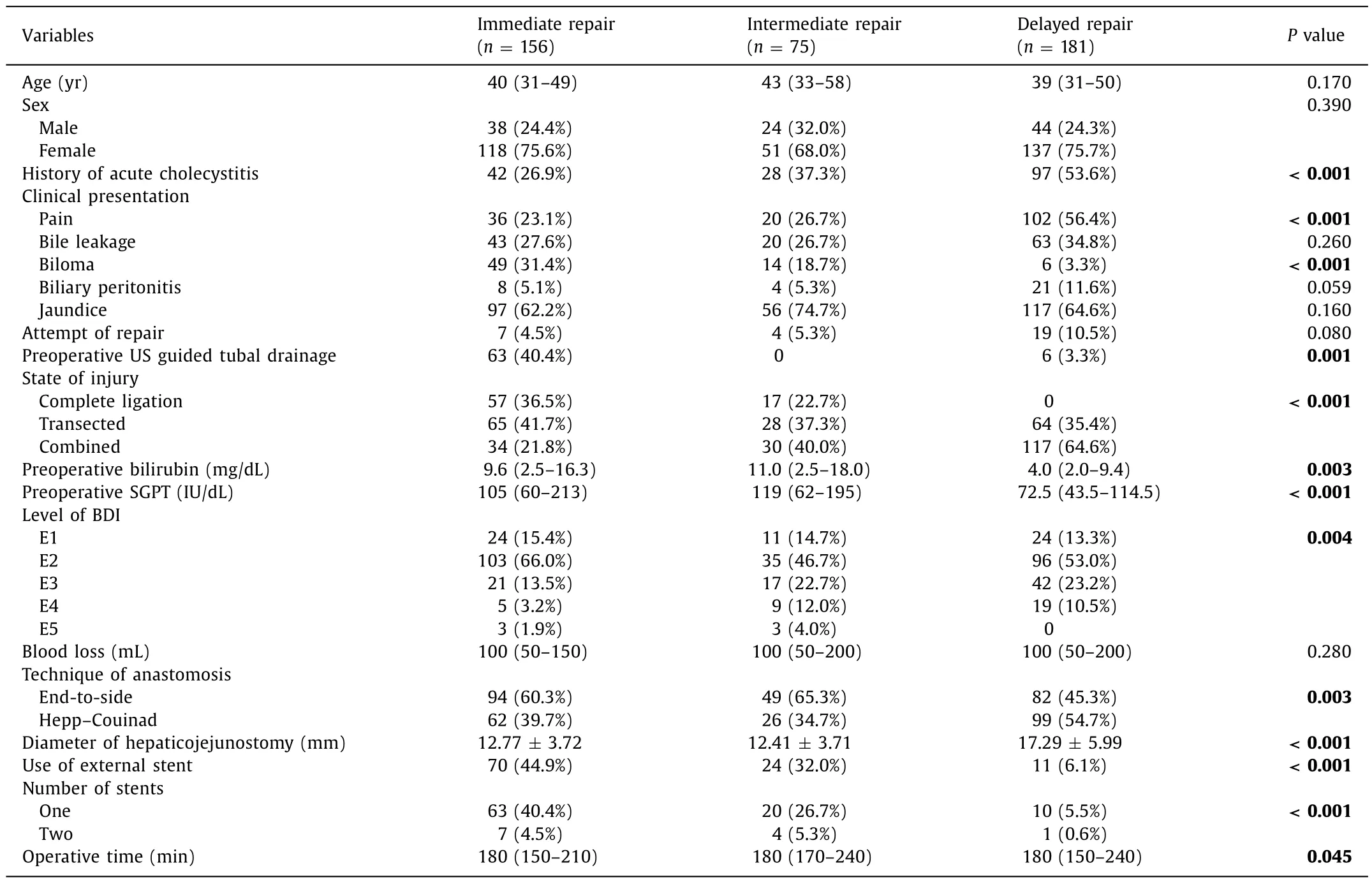

Preoperative and operative data

Demographic and preoperative data of all patients included in the study were presented in Table 1 . There were no significant differences among the three groups as regards to age, sex, the attempt of repair, and intraoperative blood loss. There were significant differences among the three groups as regards to clinical presentation, history of acute cholecystitis, preoperative serum bilirubin, ALT, state of injury, level of BDI, the technique of anastomosis,the diameter of HJ, the use of external stent, and operative time( Table 2 ).

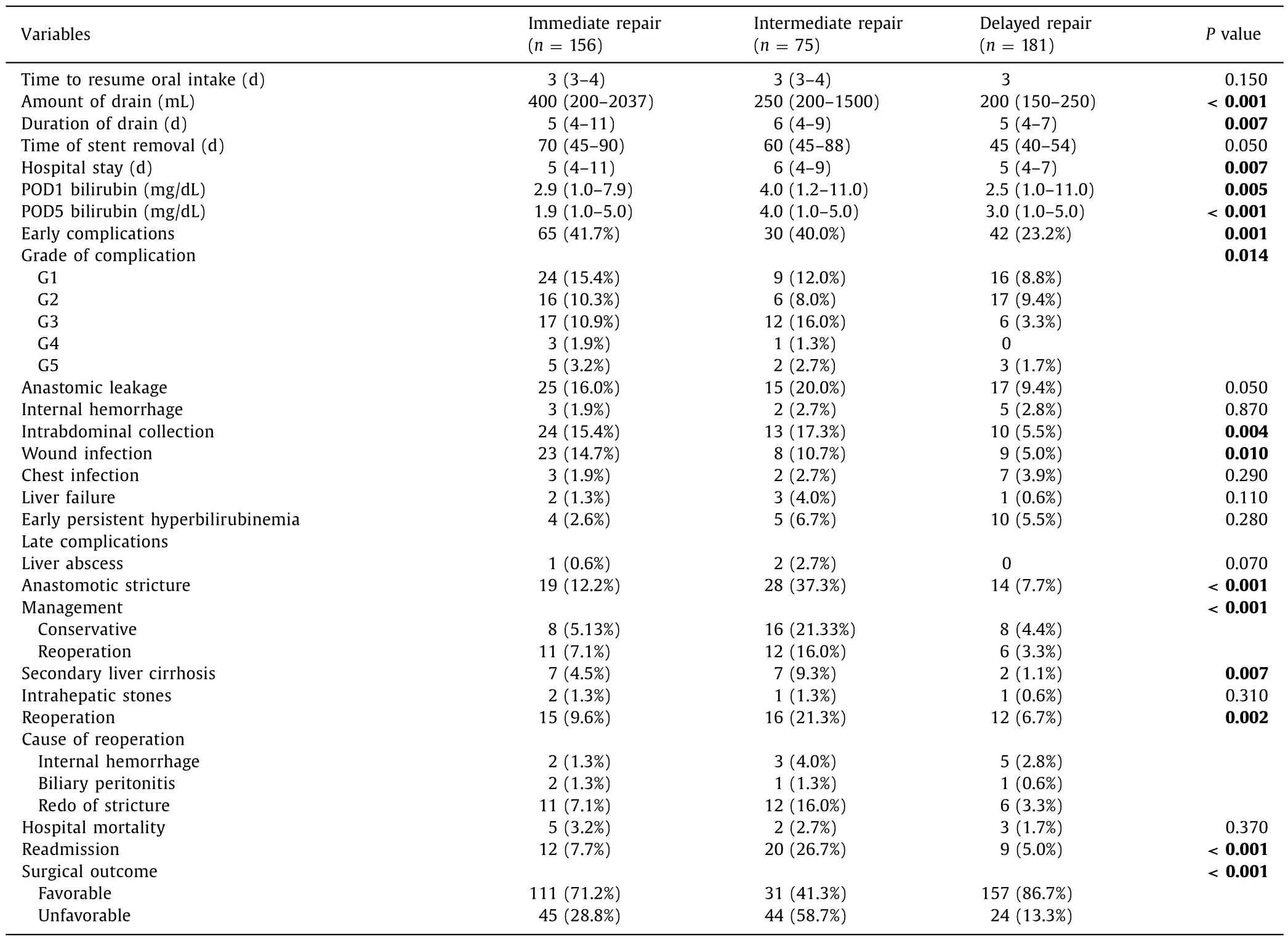

Postoperative and long-term outcomes

The duration of drain was significantly longer and amount of drainage was significantly more in group 1. The median length of hospital stay was 5 days in group 1, 6 days in group 2, and 5 days in group 3 (P= 0.007).

Early complications including anastomotic leakage and intraabdominal collection were significantly more in group 2 ( Table 3 ).Reoperation was needed in 15 (9.6%) patients in group 1 (two patients developed biliary peritonitis, two patients had internal hemorrhage and 11 patients developed anastomotic stricture), 16(21.3%) in group 2 (one patient developed biliary peritonitis, three patients had internal hemorrhage and 12 patients developed anastomotic stricture) and 12 (6.7%) in group 3 (one patient developedbiliary peritonitis, five patients had internal hemorrhage and 6 patients developed anastomotic stricture). The overall mortality rate was 2.4% (10/412). There was no significant difference among the three groups as regards to hospital mortality. Late complications including anastomotic stricture and secondary liver cirrhosis were significantly less in group 3. There were no significant differences among the three groups as regards to the development of intrahepatic stone, liver failure, early persistent hyperbilirubinemia, and liver abscess. Readmission was significantly frequent in group 2 (P<0.001, Table 3 ).

Table 2 Preoperative and intra-operative data of BDI reconstruction according to time of repair.

Univariate analysis demonstrated nine risk factors for the development of anastomotic biliary stricture including associated vascular injury (P<0.001), level of BDI (P= 0.005), transected BDI(P= 0.002), no use of external stent (P= 0.004), multiple anastomosis (P= 0.01), postoperative bile leakage (P= 0.001), postoperative abdominal collection (P= 0.008), presence of overall complications (P<0.001), and timing of the repair (P<0.001). Favorable outcome was observed in 111 (71.2%) patients in group 1, 31(41.3%) patients in group 2 and 157 (86.7%) patients in group 3 (P<0.001).

In group 1, univariate analysis demonstrated eight variables including type of initial cholecystectomy, clinical presentation of jaundice, preoperative serum bilirubin level, state of injury, level of BDI, technique of anastomosis, number of anastomosis, and the use of external stent. Multivariate analysis identified that complete bile duct ligation (P= 0.005), level E1 BDI (P= 0.047), and the use of external stent (P<0.001) were independent factors of favorable outcome. Transected bile duct (P= 0.011) was an independent factor of unfavorable outcome ( Table 4 ).

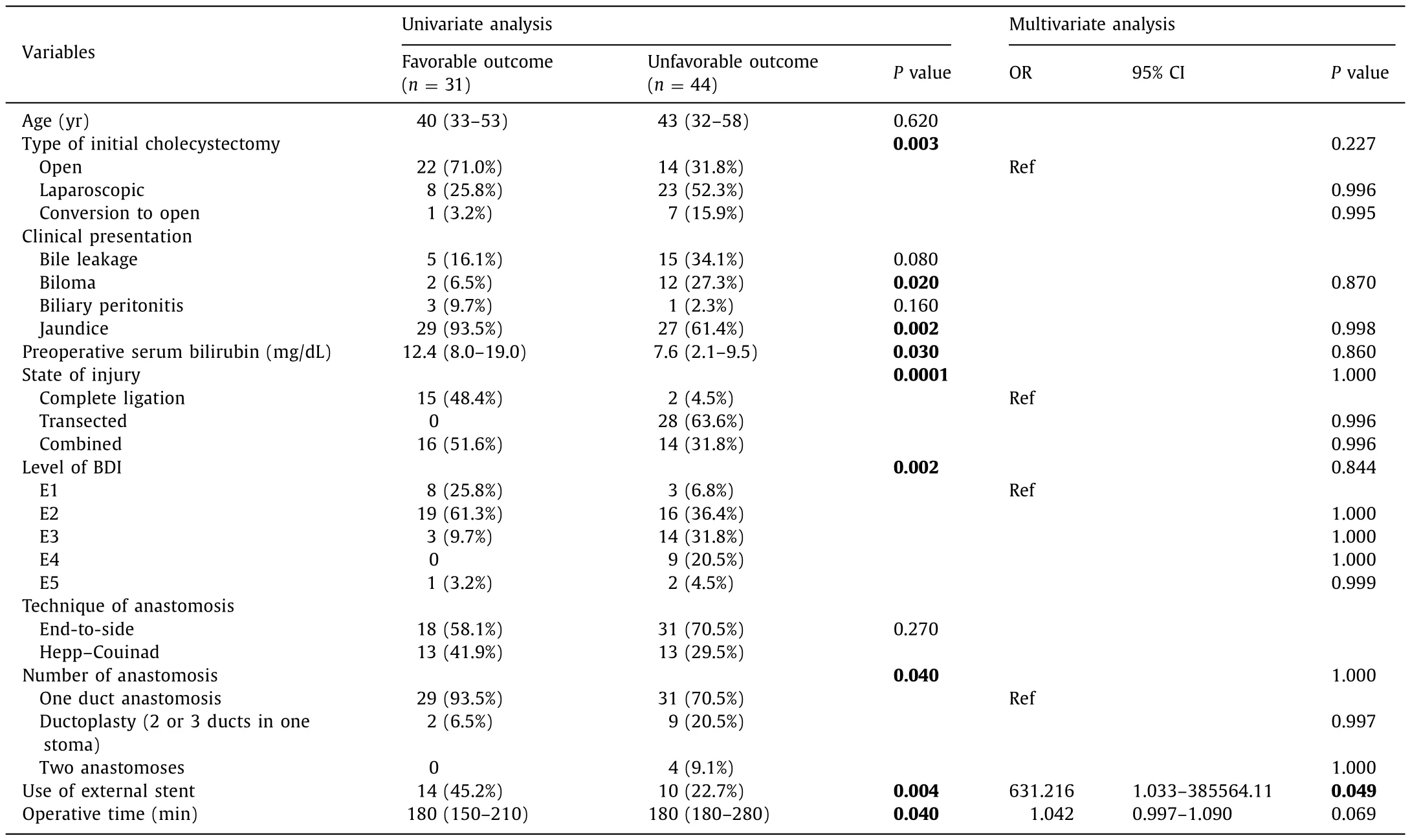

In group 2, univariate analysis demonstrated nine variables including type of initial cholecystectomy, biloma, jaundice, preoperative serum bilirubin level, state of injury, level of BDI, number of anastomosis, the use of external stent and operative time. Multivariate analysis identified that the use of external stent (P= 0.049)was an independent factor of favorable outcome ( Table 5 ).

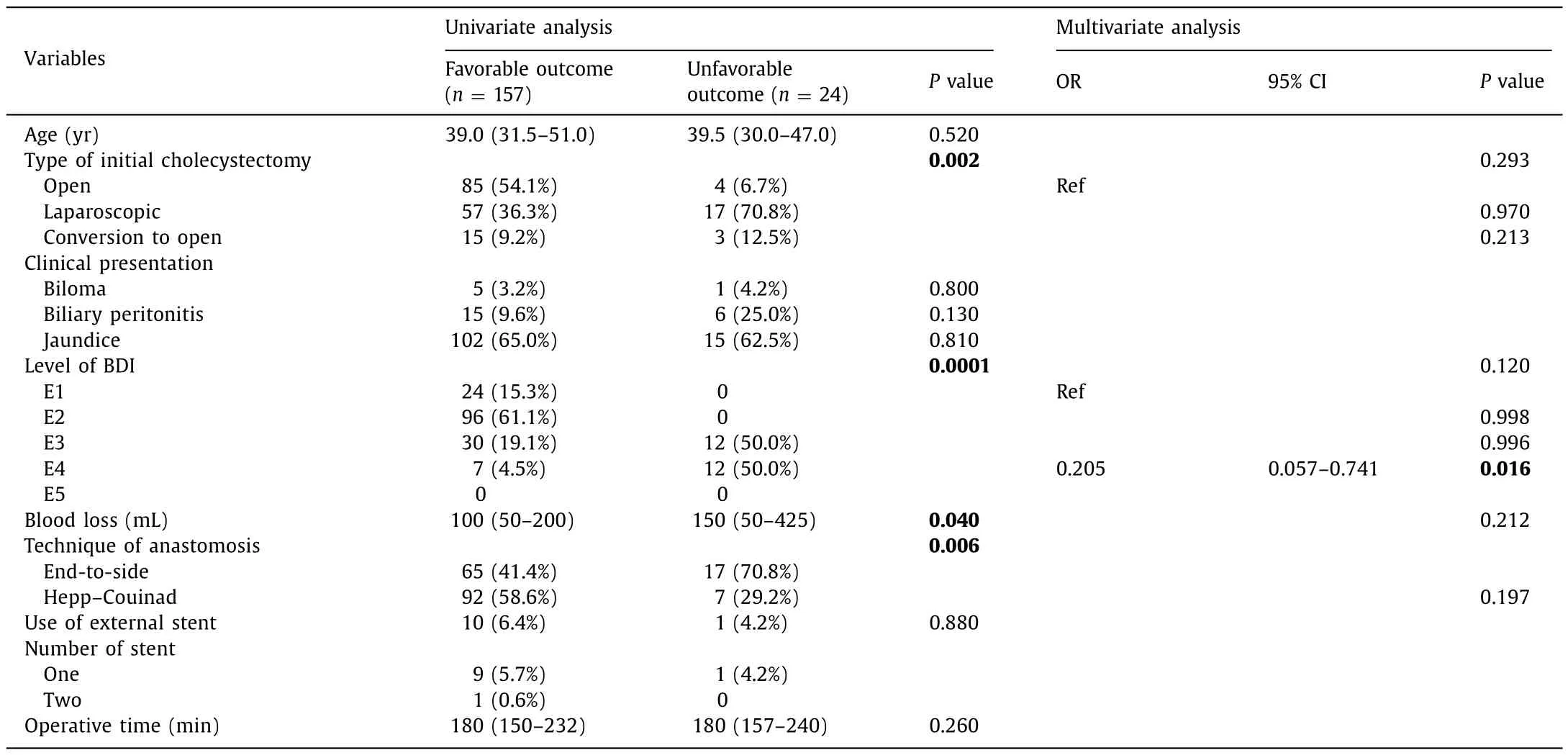

In group 3, univariate analysis demonstrated four variables including type of initial cholecystectomy, level of BDI, intraoperative blood loss and the Hepp–Couinad technique. Multivariate analysis identified that level E4 BDI (P= 0.016) was an independent factor of unfavorable outcome ( Table 6 ).

Discussion

The most common cause of BDI during cholecystectomy is difficult anatomy that leads to misidentification of the CBD or aberrant hepatic duct as the cystic duct. Difficult pathologies including Mirrizi gall bladder, post ERCP, acute cholecystitis, liver cirrhosis, contracted gall bladder and difficult techniques including inappropriate clipping and thermal damage are risk factors associated with BDI [2 –4]. Safe cholecystectomy and prevention of BDI are the main goals for any surgeon. These can be achieved by proper and safe dissection of the Calot’s triangle until reaching a critical view of safety before the division of any structure. Intraoperative cholan-giogram may have a role in difficult cases to delineate the anatomy for early detection of BDI [21].

Table 3 Surgical outcomes of post-cholecystectomy BDI reconstruction according to time of repair.

The management of patients with post-cholecystectomy BDI is a dispute even for hepatobiliary surgeons. These patients should always be referred to a specialized center for proper management due to the difficulty of these injuries [6 –9]. The availability of multidisciplinary services including hepatobiliary surgeons gastroenterologist, endoscopist, and interventional radiologist in the center is of essential importance, and these amenities and capability allow for exact identification of the injury and allow for good outcomes.

The choice of surgical reconstruction and timing of surgical repair are critical for long-term outcomes. No guideline at present shows the proper timing of post-cholecystectomy BDI repair, while few studies compared early versus late repair BDI. Surgical repair within the first 72 hours after the happening of the injury can be done safely by hepatobiliary surgery. However, a repair performed after 72 hours to 3 months after the injury, on non-dilated bile ducts due to leakage and in an inflammatory condition due to biliary peritonitis or biloma, is more difficult and hazardous due to friability of tissues and high possibility of complications.

Data from previous studies are varied concerning the timing of post-cholecystectomy BDI reconstruction. Cho et al. [22]reported that early BDI reconstruction is a preferred approach when condition allowed. Sicklick et al. [23]concluded that the timing of the operation, presenting symptoms, and history of prior repair had no impact on the incidence of postoperative complications or length of postoperative hospital stay. Sicklick et al. [23]reported that early reference to a tertiary hospital with skilled hepatobiliary surgeons and trained interventional radiologists may seem appropriate in order to ensure optimum outcome. Battal et al. [10]found that immediate surgical reconstruction of post-cholecystectomy BDIs led to a favorable outcome.

Sahajpal et al. [24]studied 69 patients with bile duct injuries and found a significant relationship between the early BDI reconstruction within 6 weeks and the prevalence of anastomotic leakage and long-term stricture of HJ [24]. Dominguez-Rosado et al. [4]observed that sepsis control and avoidance of biliary stent were independent factors to reduce the incidence of postoperative morbidities before primary reconstruction. They reported that delayed biliary reconstruction should be considered for patients presenting between 8 days and 6 weeks after BDI to prevent morbidities and there was no association between vascular injury and anastomotic failure and morbidities. Iannelli et al. [5]reported better results in those reconstructed after 45 days after BDI.

Other studies found that the same results can be achieved for patients undergoing early or delayed reconstruction of BDI [6 , 11].Stewart and Way [25]concluded that the success of biliary reconstruction for BDI depended on control of abdominal sepsis,cholangiography, use of proper surgical technique, and reconstruc-tion by an experienced hepatobiliary surgeon. If these items were found, the reconstruction could be done at any point with the expectation of an excellent outcome. They reported that there is no reason to delay the reconstruction for some arbitrary period.Multivariate analysis found that the timing of reconstruction was unimportant [25]. An European-African HepatoPancreatoBiliary Association (E-AHPBA) Research Collaborative Study management group [26]analyzed 913 patients who underwent HJ for postcholecystectomy BDI from 48 centers, and found that the timing of biliary repair in the multivariate analysis showed no impact on postoperative morbidities, the need for re-intervention after 90 days, or liver-related mortality.

Table 4 Univariate and multivariate analysis for favorable outcome of immediate HJ reconstruction.

Table 5 Univariate and multivariate analysis for favorable outcome of intermediate HJ reconstruction.

Table 6 Univariate and multivariate analysis for favorable outcome of late HJ reconstruction.

Different outcomes regarding the timing of reconstruction in the different studies may be attributed to variations in definitions of the timing of reconstruction, morbidities, and anastomotic failure and by small sample size and heterogeneous case series. A standardized tabular reporting system with clear definitions of the timing of reconstruction, morbidity, and anastomotic failure may facilitate the reporting of observational studies even among populations with different cultural, language, and health system backgrounds.

Many studies agree that a higher level of BDI is commonly related to unfavorable outcomes [3 , 9 , 17 , 26 –30]. Recent studies have found that the incidence and complexity of BDI have risen from 0.2% to 0.3% in the era of open cholecystectomy to 0.5%–0.8% in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy [1 –5 , 31 , 32]. In this study post open cholecystectomy BDI was more than post laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Open cholecystectomy is reserved now for difficult cases, for patients with unclear anatomy, Mirizzi gall bladder, history of upper abdominal surgery, unfit patients for laparoscopic surgery, or patients with acute cholecystitis. The majority of our patients were referred from peripheral hospitals. In peripheral hospital perhaps, the training in laparoscopic cholecystectomy has led to unfamiliarity in open cholecystectomy so that the ability to identify landmarks and safely perform the procedure has been diminished. Safe open cholecystectomy needed training in order to prevent BDI due to difficult cases and the causes of conversion,usually unclear anatomy, presence of complications, or anesthetic problems [33]. Ray et al. [34]reported that open cholecystectomy was the major reason for post-cholecystectomy BDI (61%) of 228 patients with a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy for BDI.

In this study, the anastomotic biliary strictures occurred more frequently in patients undergoing intermediate reconstruction. The total cases with anastomotic biliary stricture were 61 (14.8%) patients. Schreuder et al. [35]reported the incidence of anastomotic strictures ranging from 5% to 69%, with most studies reporting the incidences around 10%–20% [34 –36]. In our study, the risk factors for the development of anastomotic biliary stricture including associated vascular injury, level of biliary injury, no use of external stent, multiple anastomosis, postoperative bile leakage, transected BDI, postoperative abdominal collection, presence of overall complications, and timing of the repair result in accordance with many studies [4 , 6 , 9 , 16 –18 , 35 , 36].

In conclusion, favorable outcomes were more observed in the immediate and delayed reconstruction of post-cholecystectomy BDI. Early complications including anastomotic leakage and intraabdominal collection were significantly more in the intermediate reconstruction of BDI. Late complications including anastomotic stricture and secondary liver cirrhosis were significantly less in the late reconstruction of BDI. Complete ligation of the bile duct, level E1 BDI and use of external stent were independent factors of favorable outcome. Transected BDI and level E4 BDI were independent factors of unfavorable outcome.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ayman El Nakeeb:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Ahmad Sultan:Conceptualization, Data curation.Helmy Ezzat:Data curation.Mohamed Attia:Data curation.Mohamed Abd El-Wahab:Data curation.Taha Kayed:Data curation.Ayman Hassanen:Data curation.Ahmad AlMalki:Conceptualization, Data cura-tion.Ahmed Alqarni:Data curation.Mohammed M Mohammed:Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

The protocol of this study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Liver transplantation and BCLC classification: Limitations impede optimum treatment

- Do the existing staging systems for primary liver cancer apply to combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma?

- Overlap of concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune diseases is associated with milder disease severity of newly diagnosed autoimmune hepatitis

- Aggressive surgical approach in patients with adrenal-only metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma enables higher survival rates than standard systemic therapy

- Integrating transcriptomes and somatic mutations to identify RNA methylation regulators as a prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma

- The utility of two-dimensional shear wave elastography and texture analysis for monitoring liver fibrosis in rat model