Do the existing staging systems for primary liver cancer apply to combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma?

2021-03-05QingZhouHoCiMingHoXuYoYeXioLongLiGuoMingShiChengHungXioDongZhuJiBinCiJinZhouJiFnYunJiHuiChunSunYingHoShen

Qing Zhou , , Ho Ci , , Ming-Ho Xu , , Yo Ye , Xio-Long Li , Guo-Ming Shi ,Cheng Hung , Xio-Dong Zhu , Ji-Bin Ci , Jin Zhou , Ji Fn , Yun Ji ,Hui-Chun Sun , Ying-Ho Shen ,

a Department of Liver Surgery, Liver Cancer Institute, Zhongshan Hospital, and Key Laboratory of Carcinogenesis and Cancer Invasion (Ministry of Education), Fudan University, Shanghai 20 0 032, China

b Department of Pathology, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 20 0 032, China

Keywords:Hepatocellular carcinoma Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma Histological type Tumor staging system Prognosis Risk stratification

ABSTRACT Background: The incidence of combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma(cHCC-ICC) is relatively low, and the knowledge about the prognosis of cHCC-ICC remains obscure. In the study, we aimed to screen existing primary liver cancer staging systems and shed light on the prognosis and risk factors for cHCC-ICC.Methods: We retrospectively reviewed 206 cHCC-ICC patients who received curative surgical resection from April 1999 to March 2017. The correlation of survival measures with the histological types or with tumor staging systems was determined and predictive values of tumor staging systems with cHCC-ICC prognosis were compared.Results: The histological type was not associated with overall survival (OS) ( P = 0.338) or disease-free survival (DFS) ( P = 0.843) of patients after curative surgical resection. BCLC, TNM for HCC, and TNM for ICC stages correlated with both OS and DFS in cHCC-ICC (all P < 0.05). The predictive values of TNM for HCC and TNM for ICC stages were similar in terms of predicting postoperative OS ( P = 0.798) and DFS( P = 0.191) in cHCC-ICC. TNM for HCC was superior to BCLC for predicting postoperative OS ( P = 0.022)in cHCC-ICC.Conclusion: The TNM for HCC staging system should be prioritized for clinical applications in predicting cHCC-ICC prognosis.

Introduction

Combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-ICC) was first described in 1903 and is different from concurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) [1]. HCC or ICC is characterized with homogeneous hepatocytic or cholangiocytic cytology and architecture within the same tumor, while cHCC-ICC is classified as a distinct type of primary liver cancer [1]. Like in HCC and ICC, surgical resection remains the primary treatment option for cHCC-ICC [2]. Because the incidence of this cancer is relatively low, making up 1.0%to 4.7% of primary liver cancer [3], there is no consensus regarding risk stratification for the prognosis of cHCC-ICC after surgical resection.

According to the 2010 World Health Organization classification,there are two histological types of cHCC-ICC, a classical type and a type with stem cell features. The stem-cell-like type is further classified into three subgroups: a cholangiocellular subtype, an intermediate subtype, and a typical subtype. One theory for the origin of cHCC-ICC suggests that either the HCC component or the ICC component within the same tumor is derived from hepatic stem cells [ 2 , 4 ]. Several gene expression profile studies show that cHCC-ICC shares more common features with ICC, not HCC [ 5 , 6 ].In 2010, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) recommended that cHCC-ICC be staged by the 7th TNM (tumor, node,metastases) staging system for ICC [7]. However, there is no clinical evidence to support this recommendation. It remains to be answered whether cHCC-ICC is more similar to HCC or ICC in its clin-ical features and survival after resection. Also, because there is no specific TNM stage system for cHCC-ICC, it is necessary to further evaluate whether the existing tumor stage system for HCC or ICC is feasible for cHCC-ICC.

In this study, we aimed to determine a feasible tool to predict cHCC-ICC prognosis after resection, using the existing staging systems for HCC or ICC.

Methods

Patient inclusio n

We retrospectively reviewed all the diagnosed cHCC-ICC patients who underwent surgical resection from April 1999 to March 2017 in Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) the tumor species for each patient was independently re-assessed by two pathologists to confirm cHCCICC diagnosis, and the tumor pathological type was re-assessed; 2)the clinicopathologic information for each patient was intact and recordable; 3) the Child-Pugh classification of the patient was A or B before surgery; 4) a curative resection was performed, and no macroscopic residual was found; and 5) the patient attended routine follow-ups. Patients with the following criteria were excluded from the study: 1) the patient died within 2 months after surgery or 2) the patient was lost to follow-up. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University.Informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study.

Surgical procedure

All patients had not received anti-tumor treatment before surgery and were examined preoperatively to rule out extrahepatic metastasis and to confirm that the estimated remaining liver volume was sufficient for minimal life support (no less than 20% -40% of total liver volume, depending on the underlying liver disease) [8]. However, suspicious regional lymph node (mostly hilar lymph node) metastasis was not considered a contraindication for surgery. A total of 75 patients underwent anatomical resection and 131 underwent non-anatomical resection. Any suspicious metastasized lymph nodes (enlarged and hard in quality) were resected for a pathological examination. After sufficient exposure, the liver parenchyma was then dissected, and the passing blood vessels or bile ducts were ligated and transected. When necessary, a Pringle maneuver was used to control the hepatic inflow and reduce excessive bleeding.

Pathological examination and stage assessment

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining was performed to confirm the diagnosis of carcinoma and lymph node metastasis.Paraffin-embedded samples of the primary carcinomas from 206 patients were immunostained for HepParl, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP),CD10, carcinoembryonic antigen (pCEA), cytokeratin 7 (CK7), CK19,MOC31, neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM1/CD56), epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) and KIT(CD117). Immunostain was carried out using a Bond Max instrument (Leica Microsystems,Wetzlar, Germany). Hepatocellular component was confirmed by immunostaining with HepParl (granular cytoplasmic staining) or specific canalicular staining with anti-CD10 and/or pCEA. The biliary component was highlighted by immunostains of CK7, CK19,MOC31 or histochemical staining of periodic acid-Schiffstain after diastase digestion.

According to the 2010 WHO classification [9], classical type is defined as containing areas of typical HCC and areas of typical cholangiocarcinoma. The cHCC-ICC with stem cell features is defined as 1) typical subtype having tumor cells positive for CK7,CK19, CD56, CD117 and/or EpCAM; or 2) intermediate-cell subtype consisted of tumor cells showing simultaneous cytoplasmic expression of hepatocytic (HepParl or AFP) and cholangiocytic markers(CK19 or pCEA), as well as CD117; 3) cholangiocellular type, with tumor cells positive for CK19, CD56, EpCAM and CD117.

Follow-ups

Within the first year after surgery, patients were routinely examined at least every 2 months for AFP and cancer antigen 19-9(CA19-9) as well as by ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging scans if necessary. After that, physicians requested that patients be examined at least every 3 to 4 months. Patients also received follow-up phone calls each year. Required follow-up information included living or deceased status, the date of death (if applicable), recurrence status, and the date of recurrence (if applicable). For patients who developed tumor recurrence, the secondary treatment modalities were recorded, such as re-resection,liver transplantation, radiofrequency ablation, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. The median follow-up was 30.23 months.

Statistical analysis

We performed the statistical analysis using SPSS (version 18.0,IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative data with normal distributions are described as mean ±standard deviation. Quantitative data with non-normal distributions are described using medians with interquartile ranges. Qualitative data are described with frequencies and compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were compared using the Kaplan-Meier survival curve based on the logrank test. Variables withPvalue<0.05 in univariate analyses were subsequently entered into multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model. We used the receiver operating characteristic curve to assess the predictive value of selected parameters and calculated the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). DeLong’s test was used to compare the AUCs of different parameters. APvalue<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathologic information

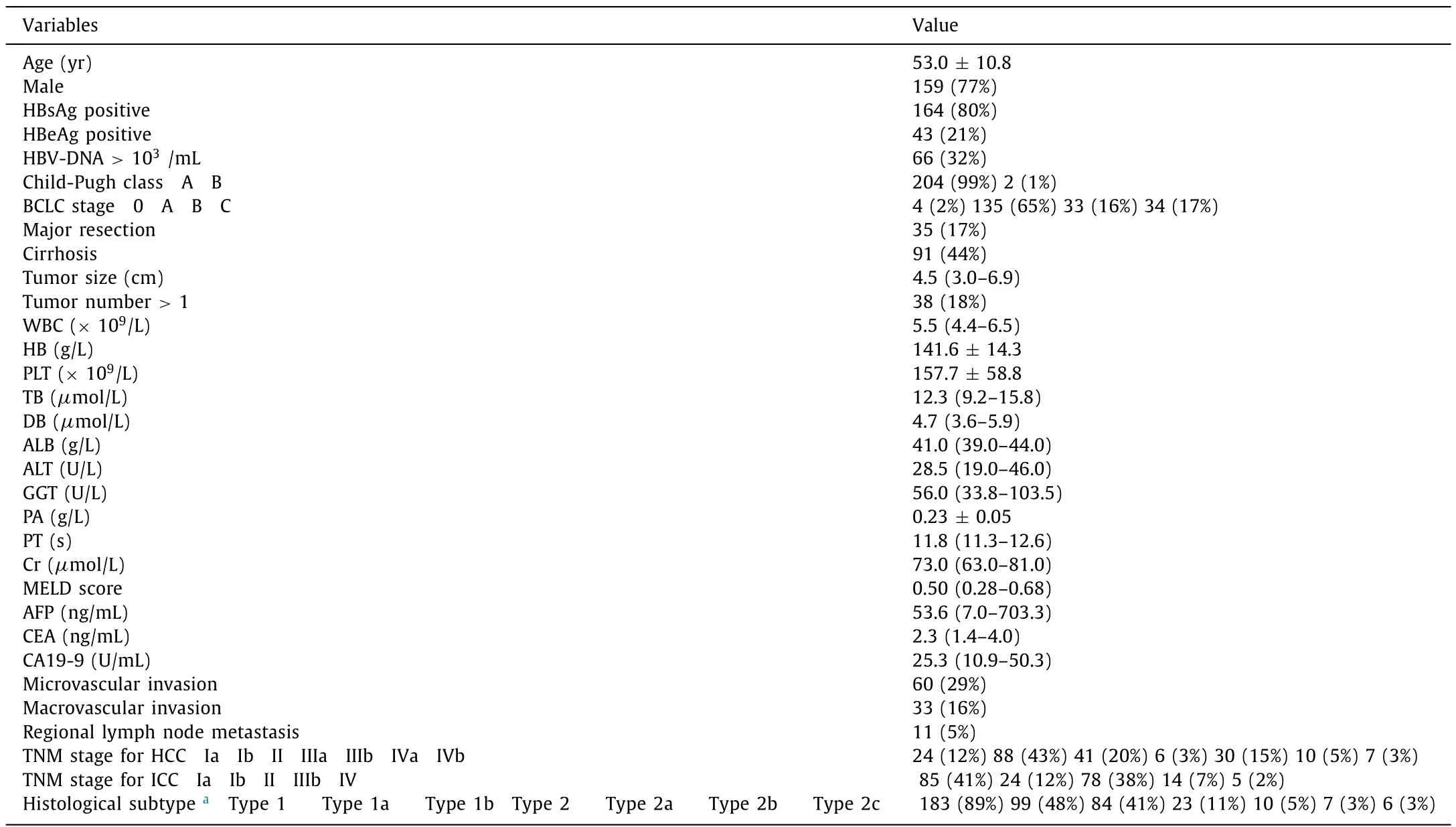

We identified 206 cHCC-ICC patients (159 males and 47 females) eligible for this study who were treated between April 1999 to March 2017. In the same period, 21 070 patients with HCC and 1167 patients with ICC underwent surgical resection in our institute. The patients with cHCC-ICC made up 0.92% of total primary liver cancers. Among these patients, 164 (80%) were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), whereas only 66 (32%) had a HBV-DNA>103/mL. We found a background of liver cirrhosis in 91(44%) patients. Patients were categorized by the TNM staging system designed for HCC or ICC and by the BCLC staging system. Most of these patients were in early stages according to TNM for HCC(Stage I + II: 74%), TNM for ICC (Stage I + II: 91%), or BCLC staging(BCLC 0 + A: 67%). The basic demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics are shown in Table 1 .

Of 206 patients after hepatectomy, 142 developed postoperative recurrence and/or metastasis. Among these patients, 25 developed solitary intrahepatic recurrence, 93 developed multiple intrahepatic recurrences, and 24 developed extrahepatic metastases; 24received re-resection, 13 received radiofrequency ablation, 50 received transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, 4 received radiotherapy, 11 received systemic treatment, and 40 received conservative therapy upon first diagnosis of tumor recurrence.

Table 1 The basic clinicopathologic characteristics of the included patients ( n = 206).

Fig. 1. Overall survival ( A ) and disease-free survival ( B ) of cHCC-ICC. cHCC-ICC: combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Survival of cHCC-ICC patients after resection

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates for cHCC-ICC were 78%, 56%,and 44%, respectively. The median OS time was 41.6 months. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year DFS rates for cHCC-ICC were 56%, 31%, and 20%,respectively. The median DFS time was 13.0 months ( Fig. 1 ).

Prognostic factors for cHCC-ICC

Univariate and multivariate analysis revealed that albumin, prothrombin time, tumor size, tumor number, microvascular invasion,and hilar lymph node metastasis were independent prognostic factors for OS. We also found that sex, albumin, tumor size, tumornumber, microvascular invasion, and hilar lymph node metastasis were independent prognostic factors for DFS ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Univariate and multivariate analysis for the prognostic value of the clinicopathologic parameters in cHCC-ICC patients.

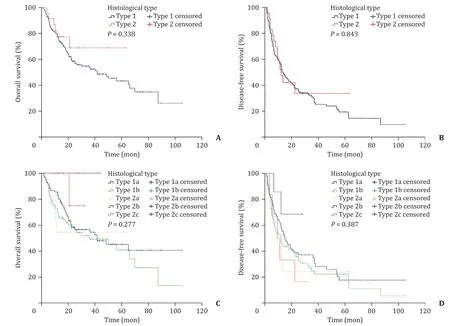

The value of histological types for evaluating cHCC-ICC prognosis

We found no correlation between the histological type and OS(P= 0.338) or DFS (P= 0.843). In a subgroup analysis of the histological subtypes of cHCC-ICC, we observed no statistical difference between any two subgroups (allP>0.05) ( Fig. 2 ). Also, the histological type did not correlate with the presence of microvascular invasion or regional lymph node metastases, which were both important independent prognostic factors for both OS and DFS (Table S1).

Evaluating patients prognosis with cHCC-ICC using different tumor staging systems

All cases were separately categorized by BCLC, TNM for HCC,and TMN for ICC staging systems. We identified associations for BCLC, TNM for HCC, and TNM for ICC stages with OS and DFS in cHCC-ICC (allP<0.05). For each tumor staging system, we performed pairwise comparisons for each stage. We found that the OS decreased as TNM for HCC stage in cHCC-ICC increased, although there was no statistical difference between stages II and III. We observed similar results for DFS time ( Fig. 3 ).

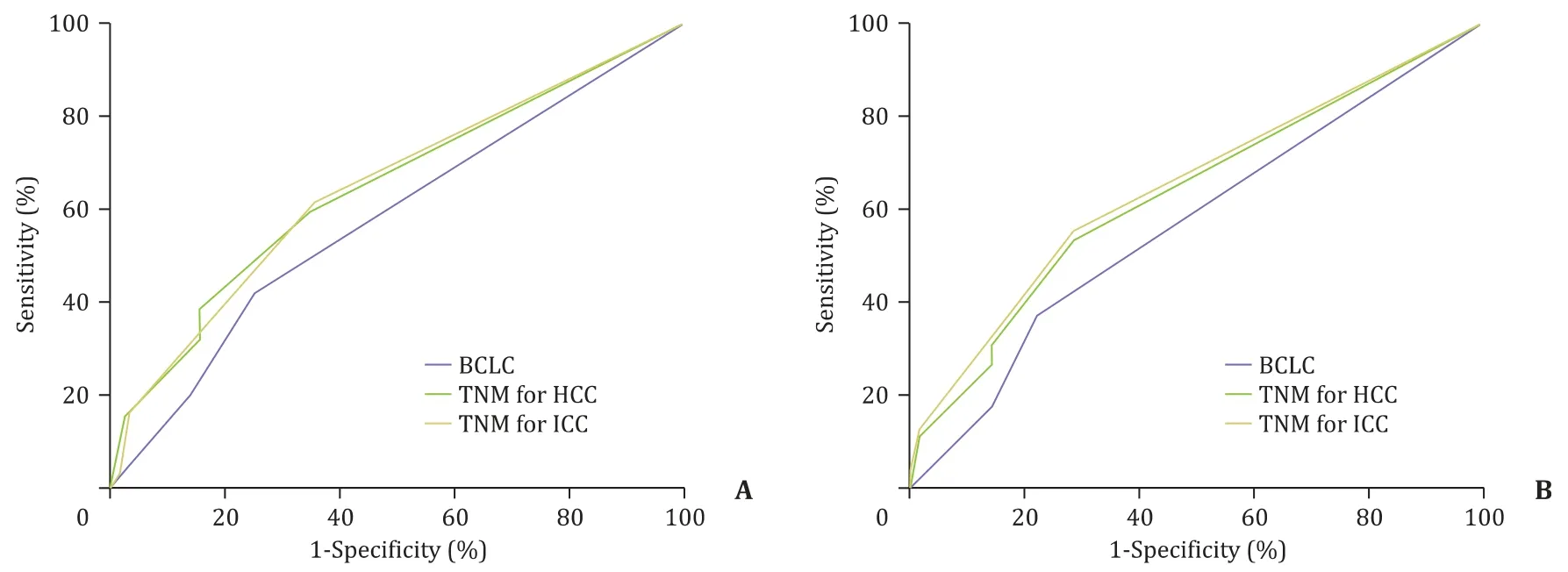

For predicting postoperative OS in cHCC-ICC, the AUCs of BCLC,TNM for HCC, and TNM for ICC staging systems were 0.582 (95%CI: 0.524–0.642), 0.650 (95% CI: 0.607–0.692) and 0.647 (95% CI:0.610–0.685), respectively ( Fig. 4 A). We found that TNM for HCC was comparable to TNM for ICC staging for predicting the postoperative OS of cHCC-ICC (P= 0.798) and that TNM for HCC was superior to BCLC for predicting postoperative OS (P= 0.022).

For predicting DFS in cHCC-ICC, the AUCs of BCLC, TNM for HCC,and TNM for ICC staging systems were 0.572 (95% CI: 0.515–0.630),0.634 (95% CI: 0.595–0.674) and 0.647 (95% CI: 0.612–0.649), respectively ( Fig. 4 B). TNM for HCC staging was comparable to TNM for ICC for predicting the DFS in cHCC-ICC (P= 0.191).

For HCC-dominant classical cHCC-ICC, the AUC comparison showed that TNM for HCC and TNM for ICC staging were equivalent for predicting postoperative OS (P= 0.061) and DFS(P= 0.091) ( Fig. 5 A and B). For ICC-dominant classical cHCC-ICC,we found that TNM for HCC and TNM for ICC staging were equivalent for predicting the postoperative OS (P= 0.360); however, TNM for HCC was inferior to TNM for ICC for predicting DFS (P= 0.020)( Fig. 5 C and D).

Discussion

In this study, we found that the TNM for HCC staging system should be prioritized for clinical applications in predicting cHCCICC prognosis. Similar to a previously published study by Akiba et al. [10], we found that the histological types of cHCC-ICC did not correlate with patient prognosis. However, Jung et al. [11]found that the histological type was associated with cHCC-ICC prognosis. To rule out the effect of different tumor stages, they included cHCC-ICC patients with a solitary tumor<6 cm and without lymph node and extrahepatic metastasis in a subgroup analysis,and found that the histological type was valuable for predicting pa-tient prognosis. The different result in our study may be attributed to the use of relatively small numbers of patients who were in advanced stages, which are usually contraindicated for curative surgical resections [12]. In our study, we also found that the histological type of cHCC-ICC was not associated with microvascular invasion and regional lymph node metastasis, which were identified as independent prognostic factors in cHCC-ICC. Because histological types showed poor value in risk stratification for cHCC-ICC prognosis, we intended to identify a simple and operable parameter to assess cHCC-ICC prognosis.

Fig. 2. Overall survival and disease-free survival for different histological subtypes of cHCC-ICC. A-B: Overall and disease-free survival of classical cHCC-ICC and cHCC-ICC with stem cell features; C-D: overall and disease-free survival of different subtypes. Type1: classical cHCC-ICC; type 2: cHCC-ICC with stem cell features; type 1a: HCC-dominant classical cHCC-ICC; type 1b: ICC-dominant cHCC-ICC; type 2a: typical subtype; type 2b: intermediate subtype; type 2c: cholangiocellular subtype. cHCC-ICC:combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

In 2017, the AJCC released the latest (8th) version of TNM staging systems [13]. However, there has been no significant change in the prognostic discrimination of ICC [13]. Additionally, there has been no update on the classification of cHCC-ICC, which is still treated as ICC. In our study, we found that TNM for HCC staging was superior to the BCLC system for predicting cHCC-ICC prognosis, and the predictive values of TNM for HCC and TNM for ICC stages were similar in terms of predicting postoperative OS and DFS in cHCC-ICC. We found statistically significant differences between each stage of the TNM for HCC system, except for stage II and III. The lack of a significant significance between stage II and III may result from the intrinsic limitation of the TNM staging system and the small number of patients at stage III. We therefore recommend that TNM for HCC staging system should be prioritized for clinical applications in predicting cHCC-ICC prognosis.

It should be noted that for predicting cHCC-ICC prognosis, the AUC of TNM for HCC and TNM for ICC were both below 0.70. It will be necessary to develop a more accurate staging system for early stage cHCC-ICC based on corresponding risk factors. Of all the independent prognostic factors for cHCC-ICC that we identified in this study, microvascular invasion and regional lymph node metastasis were important for both OS and DFS. These two prognostic factors are reflective of two metastasis pathways in cancer and are important prognostic factors for both HCC [ 14 , 15 ]and ICC [ 16 , 17 ].Macrovascular invasion, a prognostic factor of HCC and ICC [15],was not associated with cHCC-ICC prognosis, which may be due to the relatively small number of patients at the advanced stage in our study.

A previous study reported that cHCC-ICC had a lower survival rate than HCC or ICC alone [18]. Contemporaneously published results at our institute found that the prognosis for cHCC-ICC was worse than that for HCC [19]but better than that for ICC [ 19 , 20 ].Similarly, Jung et al. reported a better prognosis for cHCC-ICC than that for ICC [11]. Moreover, Yoon et al. reported that postrecurrence survival was higher in cHCC-ICC than that in ICC but lower than that in HCC [21]. However, a recent propensity scorematched (PSM) cohort showed that before PSM, the prognosis of cHCC-ICC was superior than HCC or ICC. After PSM, there was no difference in the prognosis of the three types of liver cancer. The percentage of ICC component within cHCC-ICC did not modify the poor prognosis [22], which agreed with the finding in our study that there was no statistical difference between HCC-dominant classical cHCC-ICC and ICC-dominant classical cHCC-ICC for either OS or DFS.

Fig. 3. Overall and disease-free survival of cHCC-ICC staged by TNM staging systems for HCC/ICC and BCLC score. A-B: Overall and disease-free survival of cHCC-ICC staged by BCLC score. C-D: Overall and disease-free survival of cHCC-ICC staged by TNM staging system designed for HCC. E-F: Overall and disease-free survival of cHCC-ICC staged by TNM staging system designed for ICC. HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; ICC: intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; cHCC-ICC: combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

This study has value in potentially guiding clinical practice. Although, gene profiling by microarray had revealed many genetic characterizations of cHCC-ICC including diverse range of mutations seen in HCC and ICC, which provided information on histogenesis and prognosis, much knowledge of the cHCC-ICC genetics needs to be clarified by experiment and clinical trials. Our methods are simple and tangible. When patients with primary liver cancer are classified as cHCC-ICC on histologic examination of the surgical specimens obtained after hepatectomy, surgeons can take preventive measures if TNM for HCC staging evaluation system shows poor prognosis. Preventive measures include more frequent postoperative hematological and imaging reviews. Furthermore, in this study, TNM for HCC staging system is more suitable for clinical applications in predicting cHCC-ICC prognosis, which means that postoperative treatment plan for cHCC-ICC is also similar to that for HCC including targeted drug (sorafenib, lenvatinib) and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. On the contrary, postoperative treatment plan for ICC is based on systemic chemotherapy including capecitabine, 5-FU and mitomycin C and assisted radiotherapy. Therefore, clarifying the effectiveness of TNM for HCC staging evaluation system for prediction of cHCC-ICC prognosis could assist surgeons in choosing an appropriate treatment strategy for patients to obtain good survival rate.

This study had some limitations. Firstly, we only included cHCCICC patients who received curative surgical resection in our analysis. Thus, these findings were limited to patients with resectable tumors at early stages. Secondly, patients in our study were retrospectively reviewed. This might introduce selection biases that could potentially weaken the conclusion of our results. Thirdly, due to a low cHCC-ICC incidence rate, the sample size of our study was relatively small. Low incidence also resulted in large time interval (18 years) which might have an impact on imaging staging techniques, surgical procedures, perioperative care, and survival as well. In the future, a multicentric prospective cohort study with more qualified cHCC-ICC cases would strengthen the conclusions of our study.

Fig. 4. Receiver operating characteristic curve showing performance of TNM staging systems for HCC/ICC and BCLC score in predicting the OS and DFS of cHCC-ICC. A: The performance of TNM staging systems for HCC/ICC and BCLC score in predicting the OS of cHCC-ICC. B: The performance of TNM staging systems for HCC/ICC and BCLC score in predicting the DFS of cHCC-ICC. OS: overall survival; DFS: disease-free survival; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; ICC: intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; cHCC-ICC: combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Fig. 5. Comparison of TNM staging systems for HCC and ICC in predicting the survivals of HCC/ICC-dominant classical cHCC-ICC. A-B: Comparison of TNM staging systems for HCC and ICC in predicting the OS and DFS of HCC-dominant classical cHCC-ICC; C-D: comparison of TNM staging systems for HCC and ICC in predicting the OS and DFS of ICC-dominant classical cHCC-ICC. HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; ICC: intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; cHCC-ICC: combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; OS: overall survival; DFS: disease-free survival.

In conclusion, TNM for HCC staging system should be prioritized for clinical applications in predicting cHCC-ICC prognosis.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Qiang Zhou:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis,Writing - original draft.Hao Cai:Data curation, Methodology, Visualization Writing - original draft.Ming-Hao Xu:Data curation, Investigation, Writing - original draft.Yao Ye:Data curation, Investigation, Methodology.Xiao-Long Li:Formal analysis,Supervision, Validation.Guo-Ming Shi:Data curation, Formal analysis, Software.Cheng Huang:Conceptualization, Investigation,Validation.Xiao-Dong Zhu:Methodology, Software, Visualization.Jia-Bin Cai:Supervision, Writing - review & editing.Jian Zhou:Conceptualization, Supervision.Jia Fan:Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision.Yuan Ji:Methodology,Writing - review & editing.Hui-Chuan Sun:Project administration,Writing - review & editing.Ying-Hao Shen:Conceptualization,Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai ( 17ZR1405400 ).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University. Informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.hbpd.2020.10.002 .

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Liver transplantation and BCLC classification: Limitations impede optimum treatment

- Overlap of concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune diseases is associated with milder disease severity of newly diagnosed autoimmune hepatitis

- Aggressive surgical approach in patients with adrenal-only metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma enables higher survival rates than standard systemic therapy

- Integrating transcriptomes and somatic mutations to identify RNA methylation regulators as a prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma

- The utility of two-dimensional shear wave elastography and texture analysis for monitoring liver fibrosis in rat model

- Impact of referral pattern and timing of repair on surgical outcome after reconstruction of post-cholecystectomy bile duct injury: A multicenter study