Overlap of concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune diseases is associated with milder disease severity of newly diagnosed autoimmune hepatitis

2021-03-05ToishlingHelmutRohrhWolfgngSheppFelixGunling

Tois Mühling , Helmut Rohrh , Wolfgng Shepp , Felix Gunling , ,

a Department of Gastroenterology, Internal Medicine II, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany

b Department of Pathology, Academic Teaching Hospital Bogenhausen, Technical University of Munich, Munich 81925, Germany

c Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Gastrointestinal Oncology, Academic Teaching Hospital Bogenhausen, Technical University of Munich,Munich 81925, Germany

d Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Gastrointestinal Oncology and Diabetology, Kemperhof Koblenz, Koblenz, Germany

Keywords:Autoimmune hepatitis Concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune disease Serum aminotransferase activities

ABSTRACT Background: Concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune disorders (CEHAID) are frequently observed in autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). It is not clear whether there is any prognostic significance of CEHAID on AIH. The aim of this study was to examine the prognostic impact of CEHAID and the correlation with the disease severity of AIH.Methods: This study included 65 hospitalized subjects who fulfilled the accepted criteria for AIH during an 8-year period (2009–2016). All records were manually screened for presence of associated autoimmune diseases. Disease severity of AIH was assessed by liver laboratory tests including the ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT) and liver histology.Results: Among the enrolled patients, 52 (80%) were female (median age 61 years, IQR 45–75). Fifty-six(86.2%) were classified as type-1 AIH. In 26 (40%) patients at least one additional extrahepatic autoimmune disease was diagnosed. Thirty-four subjects were referred to our hospital because of acute presentation of AIH (supposed by an acute elevation of hepatic enzymes) for subsequent liver biopsy resulting in initial diagnosis of AIH. This group was stratified into 3 subgroups: (A) AIH alone ( n = 14); (B) overlap with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) / primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) ( n = 11); and (C) with CEHAID( n = 9). AST/ALT ratio was the lowest in subgroup C (median 0.64, IQR 0.51–0.94; P = 0.023), compared to subgroup A (median 0.91, IQR 0.66–1.10) and subgroup B (median 1.10, IQR 0.89–1.36). Patients with AIH alone showed a trend to the highest grade of fibrosis (mean 2.3; 95% CI: 1.5–3.0) with no statistical significance compared to subjects with CEHAID (lowest grade of fibrosis; mean 1.5; 95% CI: 0.2–2.8;P = 0.380) whereas the ongoing inflammation was comparable.Conclusions: AST/ALT ratio and extent of fibrosis were lower in subjects with AIH and CEHAID, compared to subjects with only AIH. Therefore, the occurrence of CEHAID might be a predictor for lower disease severity of newly diagnosed acute onset AIH, possibly caused by an earlier diagnosis or different modes of damage.

Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) represents a relatively rare chronic liver disease affecting mainly female patients and is characterized by hypergammaglobulinaemia, circulating autoantibodies and an interface hepatitis on histology [1–7]. Immunosuppressive therapy often leads to rapid improvement while the prognosis of untreated cases is poor resulting in cirrhosis and liver failure. Association of AIH is common with a plethora of other extrahepatic autoimmune diseases, necessitating a careful diagnostic screening which must be performed either at initial diagnosis or during follow-up [1 , 2].

Since the clinical course is variable, the treatment decision is based on many factors including age, histopathological grading,disease severity and response of induction treatment. These fac-tors must be considered concerning the duration of maintenance therapy [1 , 2 , 8–11 ].

In several chronic liver diseases, the ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT) serves as an indicator of chronic liver disease predicting the risk for liver-related death [12–15]. In many different chronic liver diseases including hepatitis C and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), the increase of AST/ALT ratio is a non-invasive diagnostic factor for the advances of liver fibrosis [12–15].

Liver biopsy is an important tool to set the diagnosis of AIH [1 , 2]. Furthermore, it is used to monitor therapy [1 , 2 , 16 , 17].Typical hallmarks of liver histology in AIH include interface hepatitis with dense plasma cell-rich lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. The histological spectrum varies including bridging necrosis and severe inflammatory activity, especially in acute manifestation of the disease [18–24]. At initial diagnosis, the extent of fibrosis varies.About one third of affected patients already suffer from cirrhosis [1 , 2]. Therefore, liver biopsy represents an important diagnostic feature in AIH [1–2].

Concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune disorders (CEHAID) in AIH include the full spectrum of known autoimmune diseases such as autoimmune thyroiditis (e.g. Hashimoto thyroiditis and Grave’s disease), connective tissue disease (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus), vitiligo, alopecia and type-1 diabetes mellitus [1 , 2 , 25–31 ].These associated autoimmune disorders may occur before and after diagnosis of AIH. It is not clear whether CEHAIDs represent any prognostic impact on the severity of AIH or whether they are possibly related to a more aggressive phenotype of the disease.

Herein, we performed this retrospective study to examine the correlation between CEHAID and the disease severity of acute onset AIH.

Methods

Study population

The study population was assembled from a database of hospitalized patients (n= 65) of Academic Teaching Hospital Bogenhausen who had the diagnosis of AIH as defined by discharge diagnosis codes (ICD K75.4) during the 8-year period from January 2009 to December 2016. The majority of patients came from the surrounding area of our hospital and were mainly of German origin.

Patients with multiple hospitalizations were counted only once.All patient records were manually searched with special focus on presence of concurrent autoimmune diseases. There was no evidence of alcohol abuse from the history of the patients.

The analyzed population of AIH patients was collected by the coding specialists of our hospital based on past diagnosis related groups (DRGs) cases. In all cases, AIH was the main diagnosis and therefore the prerequisite for DRG revenue. In all cases, this main diagnosis was carefully based on the established international and national diagnostic criteria [1 , 2]. Furthermore, the majority of the cases analyzed in this study were even examined in detail by the medical service of the health insurance companies for plausibility of coding and billing within the DRG system. Diagnosis of AIH was based on the validated diagnostic score of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group [1 , 2].

The treatment of AIH patients in Germany is usually carried out on an outpatient basis by a registered gastroenterologist or hepatologist. Most of the AIH patients in the present study were hospitalized for liver puncture for histological confirmation of suspected AIH (e.g. based on suspicious laboratory parameters). Liver puncture was performed in Germany almost exclusively under inpatient conditions due to the potential risk of bleeding.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of all patients and patients with newly diagnosed AIH.

Patients were grouped into subjects who were referred to our hospital because of newly diagnosed acute onset AIH (e.g. supposed by an acute elevation of liver enzymes) for subsequent liver biopsy and those who were admitted for other reasons with already proven diagnosis of AIH (already under medical therapy, not biopsied in our hospital) ( Fig. 1 ). This stratification was done to analyze the histological severity of AIH at the time of initial diagnosis since immunosuppression of AIH can avoid or even reverse fibrosis of the liver [9]. Of those patients who received subsequent liver biopsy, three subgroups were stratified: (A) AIH alone; (B) overlap with PBC/primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC); and (C) with CEHAID. There are two types of AIH based on the specific autoantibodies that are present: type 1 is characterized by antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and/or smooth muscle antibodies (SMA)/anti-actin antibodies; and type 2 is characterized by antibodies to liver kidney microsome type 1 (anti-LKM1), usually in the absence of ANA and SMA [1 , 2 , 32].

Analysis of disease severity

Disease severity of AIH was assessed by laboratory tests including AST/ALT ratio and liver histology (evaluation of fibrosis according to the score by Desmet and Scheuer, grade 0–4) [33 , 34].

If liver biopsy was performed, histological staging was defined as follows: stage 0, normal; stage 1, portal inflammation; stage 2, periportal fibrosis; stage 3, septal fibrosis; and stage 4, cirrhosis. Furthermore, ongoing inflammation was assessed. In these patients, correlation of laboratory tests and histology was performed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using GraphPad Prism (Version 7.03). If not stated otherwise, data were given as median and interquartile range (IQR) or number (percentage). As not all data were normally distributed, significant differences were tested via the Kruskal–Wallis test. Significance level was defined at a level of 0.05.

Results

Among the enrolled patients, 52 (80%) were female (median 61 years, IQR 45–75). Fifty-six (86.2%) patients were classified as type-1 AIH as described above [1 , 2 , 32]. Thirty-four subjects were initially diagnosed with acute onset AIH, while the other patients were admitted to our hospital with already proven diagnosis for other reasons (e.g. due to comorbidities). Baseline parameters of all patients are shown in Table 1 .

CEHAID in AIH

An overlap of AIH with PBC or PSC could be observed in our cohort in 9 and 7 patients, respectively. Concerning extrahepatic autoimmune disease, 19 patients had one, 4 had two and 3 had three associated extrahepatic autoimmune disorders ( Table 1 ). Most fre-quently observed was an association with connective tissue diseases (n= 15), followed by autoimmune thyroid diseases (n= 10).All concurrent autoimmune diseases are presented in details in Table 2 .

Fig. 1. Study population and stratification of patients, that were either referred to our hospital because of an acute manifestation of AIH (supposed i.e. by acute elevation of liver enzymes) for liver biopsy resulting in the initial diagnosis of AIH or admitted with already proven diagnosis of AIH (biopsy not performed in our hospital). AIH: autoimmune hepatitis; PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis; CEHAID: concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune disease; AST: aspartate aminotransferase;ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

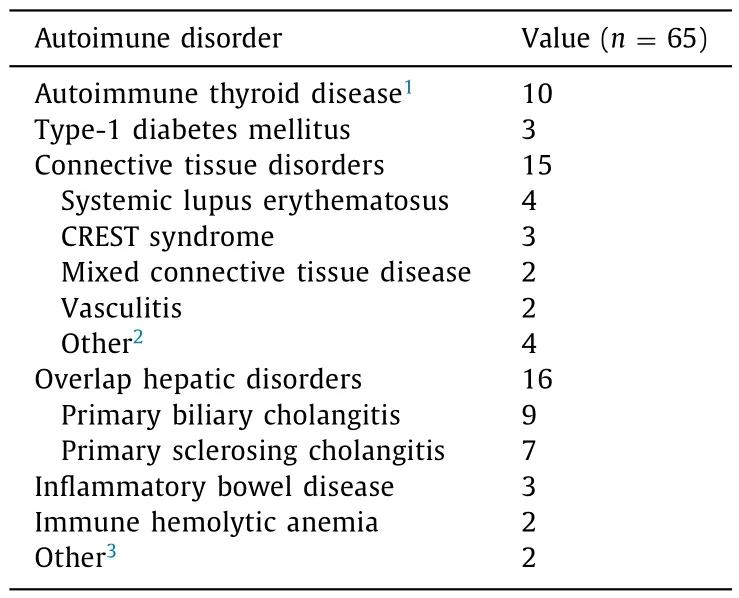

Table 2 Frequency of concurrent hepatic overlap syndromes(PBC/PSC) and extrahepatic autoimmune disease (CEHAID) in patients with autoimmune hepatitis.

Assessment of disease severity in acute onset AIH

Thirty-four subjects were referred because of newly diagnosed acute onset AIH (mostly supposed by an acute elevation of liver enzymes). In all these patients, subsequent liver biopsy was performed.

This group was stratified into 3 subgroups: (A) AIH alone(n= 14); (B) overlap with PBC/PSC (n= 11); and (C) with CEHAID(n= 9). No significant difference in age was observed comparing the three groups despite that there was a trend towards a younger age at AIH diagnosis in the CEHAID group. Severity of disease activity was assessed by evaluation of AST/ALT ratio and liver histology. AST/ALT ratio was the lowest in subgroup C (median 0.64, IQR 0.51–0.94;P= 0.023), compared to subgroup A (median 0.91, IQR 0.66–1.10) and subgroup B (median 1.10, IQR 0.89–1.36) ( Fig. 2 ).

There was no difference concerning cholestasis enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT),but a strong trend was observed for higher bilirubin values in subjects with AIH alone ( Fig. 3 and Table 3 ). All markers of general immune response or inflammation (IgG, C-reactive protein, leukocyte count) showed comparable levels ( Table 3 ). Similarly, levels of albumin were comparable among the groups. The blood sedimentation rate was only slightly increased in a few patients (10/65)without statistically significant differences.

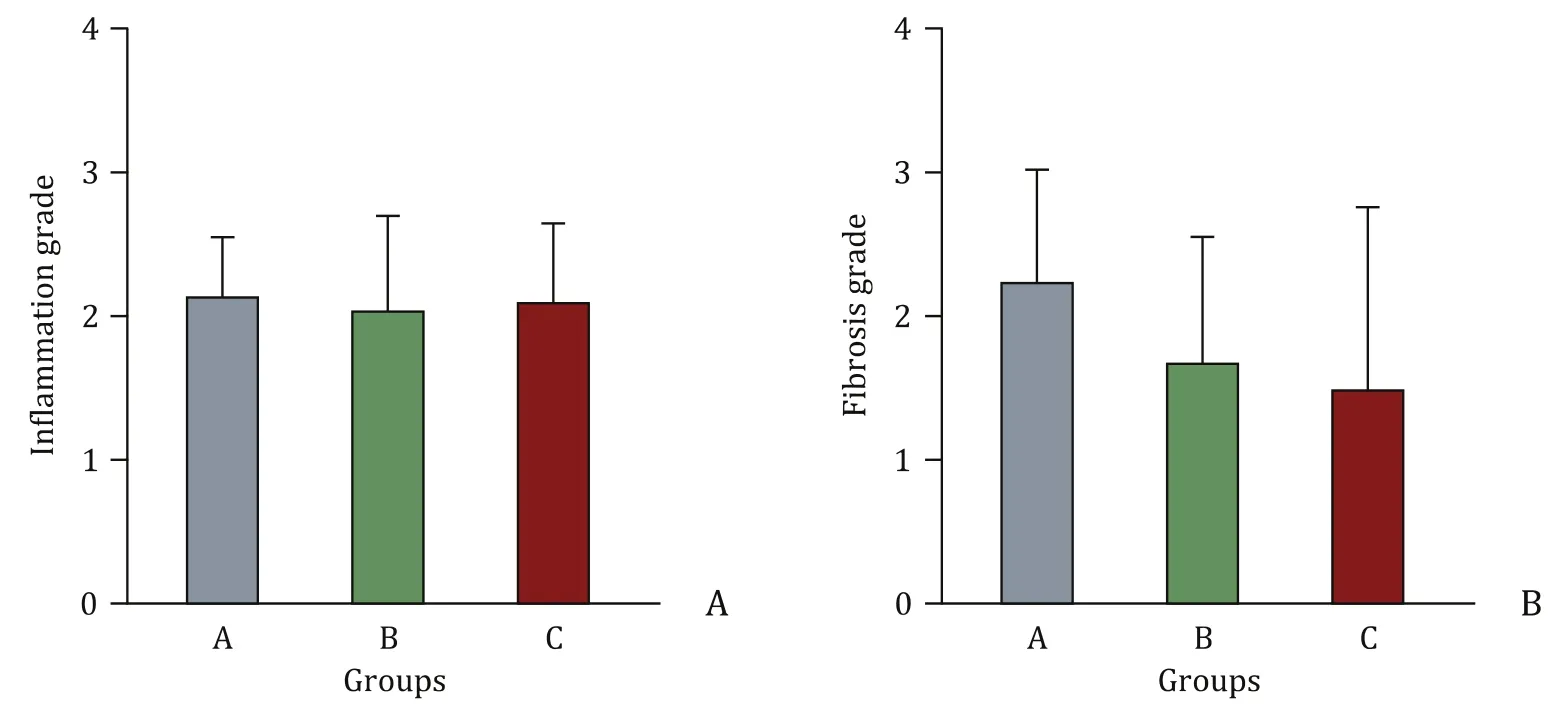

Patients with AIH alone showed a trend to the highest grade of fibrosis (mean 2.3; 95% CI: 1.5–3.0) compared to subjects with CEHAID (the lowest grade of fibrosis; mean 1.5; 95% CI: 0.2–2.8;P= 0.380) whereas the ongoing inflammation was comparable( Fig. 4 A and B). The detailed biochemical and histological parameters of these patients are shown in Table 3 .

Discussion

Overlap of CEHAID with AIH was demonstrated in numerous case reports and some cohort studies [25-31]. In a German study,Teufel et al. described an overlap of autoimmune diseases (mostly PBC and PSC) in 40% of AIH patients [27]. Efe et al. published a prevalence of 43.6% of additional extrahepatic autoimmune diseases in AIH patients [34]. Of note, 56.4% of those had at least two autoimmune disorders. Muratori et al. analyzed an Italian cohort with AIH and PBC assessing a frequency of 29.9% and 42.3%, respectively, of associated extrahepatic autoimmune diseases [33]. In their studies, the most frequent associations with AIH were found for Hashimoto disease, followed by autoimmune skin disease (including e.g. alopecia). The largest comprehensive study on this is-sue was published by Wong et al. including cohort data from 562 AIH patients which were obtained in a long period of time (ranging from 1971 to 2015) [28]. Wong et al. described a prevalence of CEHAID in 42%.

Fig. 2. Assessment of disease severity in patients with initial diagnosis of AIH by evaluation of AST ( A ), ALT ( B ) and AST/ALT ratio of all three groups ( C ) as well as AIH + PBC/PSC compared to AIH with extrahepatic manifestations ( D ). CEHAID: concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune disease. AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

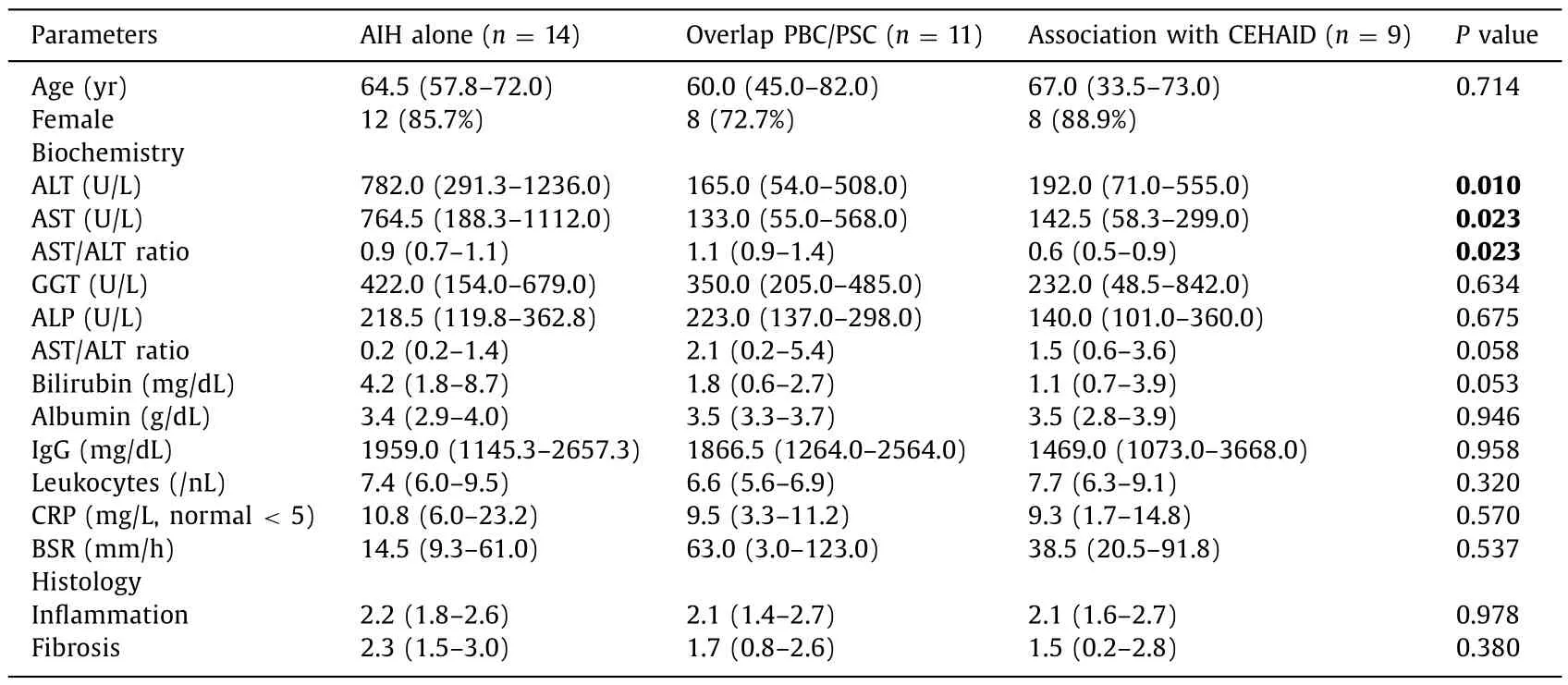

Table 3 Summarized biochemical and histological parameters of patients with initial diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis alone (AIH alone) as well as autoimmune hepatitis in the presence of either PSC/PBC (overlap) or extrahepatic manifestations (CEHAID).

Fig. 3. Association of different hepatic and inflammatory laboratory parameters in patients with initial diagnosis of AIH who were stratified into 3 subgroups (A: AIH alone;B: overlap with PBC/PSC; and C: association with CEHAID). There was no difference concerning plasma levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyltransferase(GGT), but a strong trend was observed for higher bilirubin levels in patients with AIH alone. CEHAID: concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune disease; AIH: autoimmune hepatitis; PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Fig. 4. Association of different histologic parameters in patients with initial diagnosis of AIH who were stratified into 3 subgroups (A: AIH alone; B: overlap with PBC/PSC;and C: association with CEHAID). CEHAID: concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune disease; AIH: autoimmune hepatitis; PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis.

In our cohort, 40% AIH patients had at least one additional autoimmune disease, while 11% of our study population suffered from at least two associated autoimmune disorders. The most frequent autoimmune diseases which could be diagnosed in our study were an overlap of autoimmune liver diseases (PBC and PSC), followed by an association with connective tissue diseases and autoimmune thyroid diseases.

Of note, an overlap of a PBC with AIH was described with varying frequency of about 1% to 25% [2 , 3]. What is more, in up to 10% of patients with PSC, additional overlap syndrome with au-toimmune hepatitis has been described. Especially PSC patients with significantly elevated aminotransferase and serum IgG levels should be considered for additional AIH [29–31].

The onset of CEHAID may predate, coincide or occur years after diagnosis of AIH [1 , 2 , 28]. It is not clear whether CEHAIDs represent any prognostic impact on the severity of AIH or whether they are possibly related to a more aggressive phenotype of the disease. Muratori et al. firstly reported lower liver enzymes (including bilirubin, AST and ALT) in AIH patients with associated CEHAID while patients with exclusive AIH showed higher values. This implies that such coincidence might be related with a milder course of the disease [33]. However, there was no documentation concerning fibrosis stage in their publication. Wong et al. described for the first time that presence of CEHAID may affect the clinical phenotype of AIH portending milder disease activity [28]. When additional autoimmune disorders were diagnosed, they observed less reactivity to smooth muscle antibodies, a tendency to mild fibrosis at diagnosis and less often ascites and coagulopathy [28].

In conclusion, since specific treatment by immunosuppressive therapy can prevent or reverse hepatic fibrosis, a potential impact of CEHAID on disease severity and clinical phenotype should be analyzed in patients with newly diagnosed AIH [8 , 9]. Although AIH patients clearly show an ‘‘Achilles heel” for associated autoimmune disorders, the occurrence of CEHAID might be a predictor for lower disease severity of newly diagnosed acute onset AIH. Reasons for this observation might be possibly due to an earlier diagnosis or different modes of damage. Therefore, this coincidence might have practical implications on the treatment strategy, concerning duration of therapy. The simple calculation of AST/ALT ratio seems to be a reliable tool to calculate disease activity in AIH. Larger studies are necessary to confirm our observations.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tobias Mühling:Data curation, Formal analysis.Helmut Rohrbach:Investigation.Wolfgang Schepp:Conceptualization,Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Felix Gundling:Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the regional Ethics Committees in the geographic area (Bayerische Ärztekammer).

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Liver transplantation and BCLC classification: Limitations impede optimum treatment

- Do the existing staging systems for primary liver cancer apply to combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma?

- Aggressive surgical approach in patients with adrenal-only metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma enables higher survival rates than standard systemic therapy

- Integrating transcriptomes and somatic mutations to identify RNA methylation regulators as a prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma

- The utility of two-dimensional shear wave elastography and texture analysis for monitoring liver fibrosis in rat model

- Impact of referral pattern and timing of repair on surgical outcome after reconstruction of post-cholecystectomy bile duct injury: A multicenter study