Aggressive surgical approach in patients with adrenal-only metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma enables higher survival rates than standard systemic therapy

2021-03-05SorinAlxnrsuAinECroitoruRzvnTGrigoriDnRTomsuGrilDroMugurGrsuIrinlPopsu

Sorin T Alxnrsu , ,,, AinE Croitoru , , , RzvnT Grigori , DnR Tomsu , ,Gril Dro , , Mugur C Grsu , , Irinl Popsu ,

a Dan Setlacec Centre of General Surgery and Liver Transplantation, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest 022328, Romania

b Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest 020021, Romania

c Department of Oncology, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest 022328, Romania

d Faculty of Medicine, Titu Maiorescu University, Bucharest 031593, Romania

e Dan Tulbure Centre of Anesteziology and Intensive Care, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest 022328, Romania

f Department of Radiology, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest 022328, Romania

Keywords:Adrenal metastases Hepatocellular carcinoma Adrenal resection Sorafenib Survival

ABSTRACT Background: Although guidelines recommend systemic therapy even in patients with limited extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a few recent studies suggested a potential benefit for resection of extrahepatic metastases. However, the benefit of adrenal resection (AR) for adrenal-only metastases (AOM) from HCC was not proved yet. This is the first study to compare long-term outcomes of AR to those of sorafenib in patients with AOM from HCC.Methods: The patients with adrenal metastases (AM) from HCC were identified from the electronic records of the institution between January 2002 and December 2018. Those who presented AM and other sites of extrahepatic disease were excluded. Furthermore, the patients with AOM who received other therapies than AR or sorafenib were excluded.Results: A total of 34 patients with AM from HCC were treated. Out of these, 22 patients had AOM, 6 receiving other treatment than AR or sorafenib. Eventually, 8 patients with AOM underwent AR (AR group),while 8 patients were treated with sorafenib (SOR group). The baseline characteristics of the two groups were not significantly different in terms of age, sex, number and size of the primary tumor, timing of AM diagnosis, Child-Pugh and ECOG status. After a median follow-up of 15.5 months, in the AR group, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rates (85.7%, 42.9%, and 0%, respectively) were significantly higher than those achieved in the SOR group (62.5%, 0% and 0% at 1-, 3- and 5-year, respectively) ( P = 0.009). The median progression-free survival after AR (14 months) was significantly longer than that after sorafenib therapy (6 months, P = 0.002).Conclusions: In patients with AOM from HCC, AR was associated with significantly higher overall and progression-free survival rates than systemic therapy with sorafenib. These results could represent a starting-point for future phase II/III clinical trials.

Introduction

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) consider that sorafenib is the preferred first-line treatment for patients with metastatic HCC (mHCC) [ 1 , 2 ]. Recently, lenvatinib showed noninferiority efficacy compared with sorafenib [ 1 , 2 ], thus represent-ing an alternative to sorafenib as the first-line treatment of these patients. However, no one of these guidelines consider resection of the metastases as a therapeutic option for patients with mHCC [ 1 , 2 ]. During the last decade, a few papers suggested that complete resection of extrahepatic metastases from HCC seems to prolong survival in selected mHCC patients [ 3 , 4 ].

Adrenal metastases (AM) represent the third most frequent extrahepatic metastases from HCC (after lung and bone), ranging between 6.9% and 19.1% of the patients with extrahepatic metastases [ 5 , 6 ]. However, most of these patients present both AM and metastases involving other organs (e.g. lungs, bones, lymph nodes).For such patients, systemic treatment represents the only therapeutic approach. Hence, during the last two decades, adrenal resection (AR) has been considered in a limited number of selected patients with adrenal-only metastases (AOM) from HCC. But, a retrospective study published in 2002 did not reveal any survival benefit for patients who underwent AR, compared with patients who underwent transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) for the patients with AOM [7].Consequently, in present, for the patients with AOM from HCC,most specialists still recommend palliative treatment with sorafenib [ 1 , 2 ].

Although a few recent small retrospective studies suggested that AR could prolong survival [ 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 ]in patients with AOM from HCC, no one compared the survival outcomes of AR to those treated with sorafenib. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to compare the overall survival (OS) rates achieved by AR to those achieved by the systemic treatment with sorafenib, in patients with AOM from HCC, treated in a single tertiary center. The results of such a retrospective study could represent a startingpoint for future phase II/III clinical trials comparing surgery to sorafenib in patients with AOM from HCC.

Methods

All the patients who were discharged with the diagnosis of AM and HCC were identified from the electronic database of the institution. The patients who had extrahepatic metastases concomitant with AM were excluded from the study, as well as the patients with AOM who received other therapies than sorafenib or AR (e.g. best supportive care, doxorubicin). Eventually, only the patients with AOM treated by AR (AR group) or sorafenib (SOR group)were enrolled in this study. These patients were divided into two groups, depending on the treatment received (AR group vs. SOR group) ( Fig. 1 ).

The data about the demographics of the patients, the liver function, the characteristics of HCC and AOM, the treatment addressed to the primary tumor and AOM, the postoperative results, the recurrence after operation and its treatment, as well as the survival after the diagnosis of AM, were evaluated and compared between the two groups.

Diagnosis of HCC

Because all the patients were cirrhotic and the tumors were larger than 1 cm, the diagnosis of HCC was established by at least one dynamic imaging [contrast-enhanced computed tomography(CT) scan or/and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)]. Moreover,in patients who underwent liver resection or liver transplantation(LT) the imagistic diagnosis was confirmed by histology.

Diagnosis of AOM

Fig. 1. Flow chart of included and excluded patients with AM from HCC. AM:adrenal metastases; AOM: adrenal-only metastases; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma;EM: extrahepatic metastases.

Diagnosis of AOM was based on abdominal CT scan or MRI. In the AR group, the diagnosis was confirmed by histology. In the SOR group, the diagnosis was confirmed by a subsequent abdominal CT scan or MRI (performed 2-3 months after initial detection of AOM).In all the patients, other metastatic sites were ruled out by CT scan of the thorax and CT scan or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis.

Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications were considered in those conditions that induce a deviation from the normal postoperative course, requiring either pharmacological treatment or surgical, endoscopic or radiologic therapy [10]. The grading of the postoperative complications was done according to Clavien-Dindo classification of postoperative complications [10].

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)

PFS was calculated as the time span from the AOM diagnosis to the progression of malignancy (usually detected by CT scan or MRI), or until the last follow-up (if progressive disease was not identified at that moment).

OS represented the interval between the AOM diagnosis and the death of the patient or the last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk’sWtest,P<0.05), thus were presented as median (interquartile range) and Mann-Whitney test was used to perform the comparison between the two groups. Categorical variables were presented as number (percentages) and were compared with Fisher’s exact test. The survival rates were estimated with Kaplan-Meier method, and were compared by log-rank test. The differences were considered as statistically significant forPvalue<0.05.

Results

Between January 2002 and December 2018, 34 patients with AM from HCC were evaluated in our hospital. Out of these, 12 patients were excluded from the study because they had AM con-comitant with other extrahepatic metastases from HCC. Among the 22 patients with AOM, 6 received other therapies than sorafenib or AR (e.g. best supportive care, doxorubicin). Eventually, 16 patients met the criteria to be enrolled in this study, being treated either by AR (AR group,n= 8) or sorafenib (SOR group,n= 8) ( Fig. 1 ).

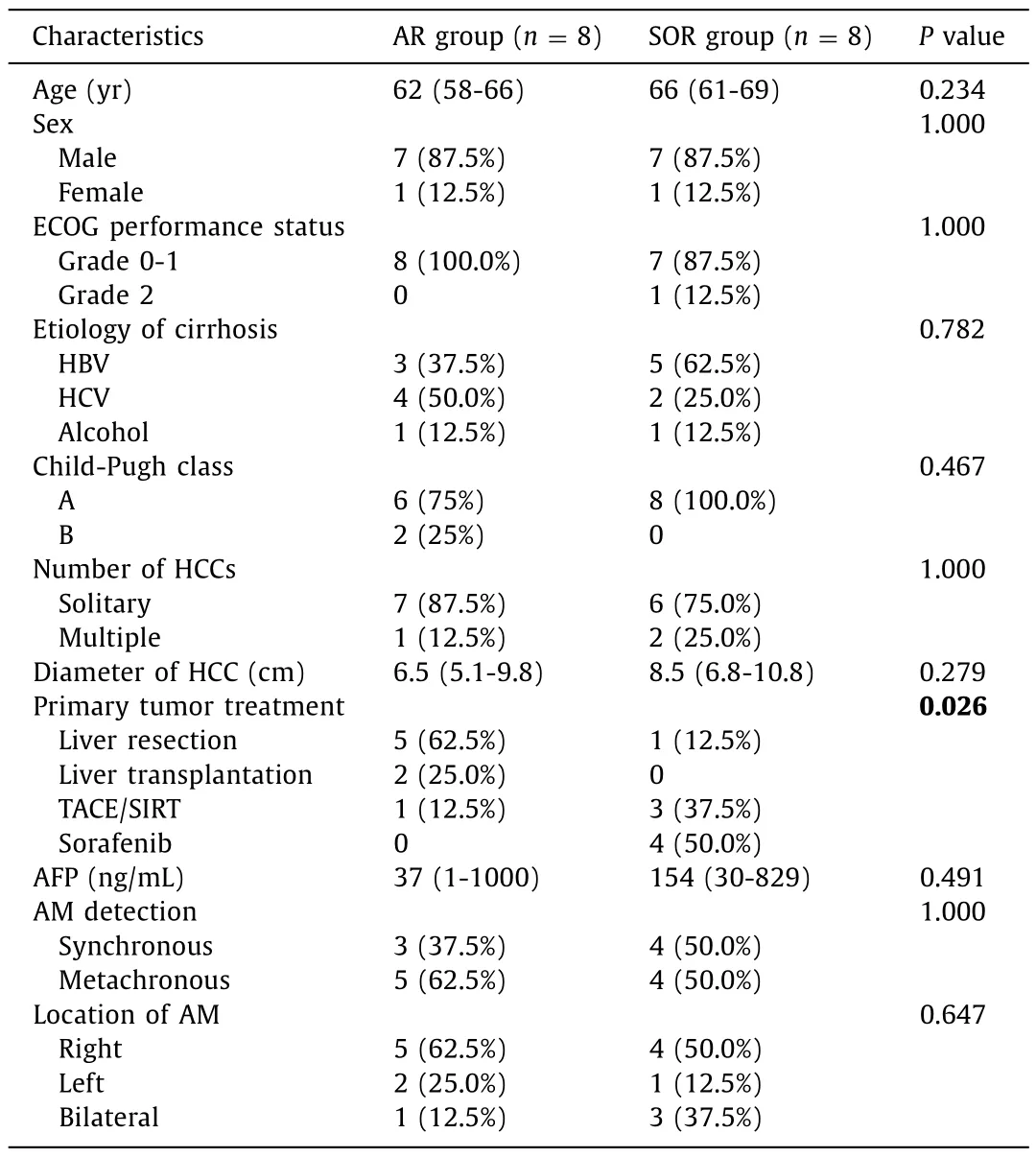

Table 1 Comparative characteristics of the two groups (AR group vs. SOR group).

Demographics of the patients

In the AR group, the median age of the patients at the time of AOM diagnosis was 62 (58-66) years, while in the SOR group, the median age was 66 (61-69) years (P= 0.234). Sex distribution was similar in the two groups ( Table 1 ).

Liver function

At the time of HCC diagnosis, all the patients had liver cirrhosis, by different etiologies ( Table 1 ). Although in the AR group the most frequent cause of liver cirrhosis was HCV infection, while in the SOR group the leading cause of cirrhosis was HBV infection,but the difference between the two groups regarding the causes of liver cirrhosis was not statistically significant (P= 0.782).

At the time of primary tumor diagnosis, Child-Pugh class A liver cirrhosis was observed in 14 out of 16 patients, while two patients presented Child-Pugh class B cirrhosis. The latter two patients underwent LT, and subsequently they developed metachronous AOM,without recurrence of cirrhosis. Thus, at the time of AOM diagnosis, 14 patients had Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, and 2 patients did not present cirrhosis (those who underwent LT).

Performance status

The ECOG status of all the patients in the AR group was 0-1, while in the SOR group 7 patients had a 0-1 ECOG status and in one patient the ECOG performance status was 2. The difference was not statistically significant between the two groups(P= 1.0 0 0).

Primary tumor

In the AR group, 7 out of 8 patients had only one liver tumor, while in the SOR group, 6 out of 8 patients presented with one liver tumor. The incidence of solitary HCC was similar in the two groups (P= 1.0 0 0) ( Table 1 ). The median diameter of the HCC was not significantly different between the two groups (P= 0.279,Table 1 ).

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)

The median level of AFP for those patients in the SOR group was not significantly different com pared to those in the AR group(P= 0.491, Table 1 ).

AOM

In the AR group, 3 patients presented AOM at the time of primary tumor detection (synchronous AOM), and 5 patients developed AOM after the treatment of the primary tumor(metachronous AOM): 2 after liver resection (11 and 23 months,respectively); 2 after LT (20 and 65 months, respectively); 1 after TACE (56 months).

In the SOR group, 4 patients presented synchronous AOM and 4 developed metachronous AOM: 16 months after liver resection; 11 months after selective internal radiation therapy; 5 and 17 months,respectively, after TACE.

Regarding the time interval until AOM diagnosis, there was no significant difference between the two groups (P= 0.234).

Treatment of AOM in the AR group

In patients with synchronous AOM, the resection of the primary tumor and AM was performed at the same time by open approach.The patients who developed metachronous AOM underwent AR,also by open approach.

After AR two patients received adjuvant chemotherapy(doxorubicin–6 cycles, and 5-fluorouracil and doxorubicin–6 cycles, respectively), while the other 6 patients did not receive adjuvant therapy.

Treatment of AOM in the SOR group

Patients with HCC and synchronous AOM received sorafenib treatment. The four patients who developed metachronous AOM underwent local therapy for their primary tumor and received sorafenib at the moment of metastases detection.

PFS

After a median follow-up of 15.5 months, 6 out of 8 patients in the AR group had recurrence. Thus, in the AR group, the PFS rates at 1-, 2-, and 3-year were 72.9%, 21.9%, and 0%, respectively,and the median PFS was 14 months. In the SOR group, the 1-year PFS rate was 0%, with a median PFS of 6 months. The difference between the PFS rates in the AR group and the SOR group was statistically significant (P= 0.002, Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2. Comparative progression-free survival curves in the two groups (AR group vs. SOR group). AR: adrenal resection; SOR: sorafenib.

Fig. 3. Comparative overall survival curves in the two groups (AR group vs. SOR group). AR: adrenal resection; SOR: sorafenib.

Treatment after progression of disease

Upon recurrence, in the AR group, 3 patients received sorafenib,one received doxorubicin, and one received 5-fluorouracil and calcium folinate. The sixth patient received best supportive care. In the SOR group, upon progression after sorafenib, 5 patients received best supportive care and 3 patients continued with sorafenib.

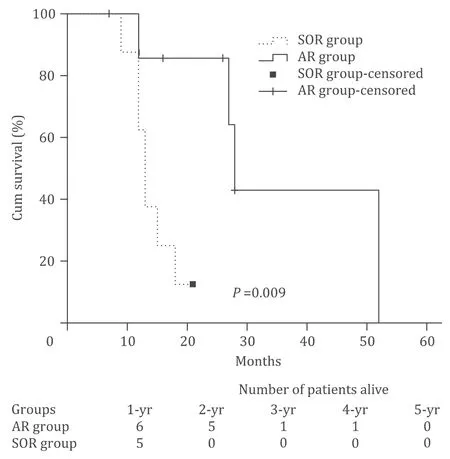

OS

In the AR group, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 85.7%,42.9%, and 0%, respectively. In the SOR group, the 1-, 3- and 5-year OS rates were 62.5%, 0% and 0%, respectively. The median OS in the AR group (28 months) was significantly higher than that in the SOR group (13 months,P= 0.009; Fig. 3 ).

Discussion

Several recent studies reported that in selected patients with limited extrahepatic metastases from HCC, extrahepatic metastasectomy improves survival, compared to patients who received non-surgical therapy for their metastatic disease [ 4 , 5 ]. A study published in 2016 revealed that in mHCC, median survival after extrahepatic metastasectomy (27.2 months) was significantly longer than those observed in patients treated with sorafenib (7.4 months,P<0.001) [4]. However, in the above-mentioned study, the highest median survival reported after extrahepatic metastasectomy was achieved in patients presenting lung metastases (36.6 months),while the lowest median survival was observed in patients with AOM (17.3 months) [4]. Similarly, Momoi et al. [7]and Hornstein et al. [11]reported median survival up to 14 months after AR for AOM from HCC. Thus, the benefit of AR vs. sorafenib in the treatment of AOM from HCC is not clearly established yet.

In the present study, the PFS and OS rates achieved by AR were significantly higher than those observed after sorafenib therapy.The median OS in the AR group was also significantly longer than that in the SOR group. This long-term outcomes achieved in the AR group are similar to those reported by Asan Medical Center group at 1- and 3-year following AR for metachronous AOM developed after liver resection for HCC (OS rates at 1-, 3- and 5-year were 94.1%, 38%, and 20.3%, respectively) [8]. The better 5-year OS rate reported by these authors could be explained by the fact that in their group all the patients presented metachronous metastases, while in the present series 37.5% of patients presented synchronous metastases. The favorable influence of a longer diseasefree interval between primary tumor resection and the diagnosis of AOM could be hypothesized, by extrapolation of the results of a few recent studies. Two studies revealed that a longer disease-free interval between HCC resection and lung metastases diagnosis was associated with significantly longer OS after pneumectomy [ 12 , 13 ].Furthermore, Ha et al. revealed that the mean interval between the liver resection for HCC and AR was 18.3 ±14.4 months, while the mean interval between LT for HCC and AR was 42.6 ±13.8 months [8]. The longer disease-free interval in patients who underwent LT was associated with higher survival rates in such patients (5-year OS was 85.7% after LT vs. 20.3% after liver resection) [8]. A similar observation was presented in 2018 by Teegen et al. who revealed that their patients receiving LT for HCC developed AOM after a longer disease-free interval (37 months)than those treated by liver resection (16.3 months), and OS rates after AR were also higher in the LT group [6]. Because usually the patients who receive LT are highly selected regarding the biologic behavior of the HCC, the authors concluded that favorable tumor biology might greatly influence the survival outcome [8]. Thus, a longer disease-free interval could be seen as a surrogate for more favorable tumor biology, and might allow for a better selection of patients in the prospect of AR.

Moreover, to achieve a longer disease-free interval after surgery,effective adjuvant therapies are needed. Because sorafenib as adjuvant treatment after curative-intent resection of HCC did not reveal any benefit in terms of overall and disease-free survival [14], other therapeutic agents could represent an option. Thus, in patients with advanced or mHCCs, progressive after sorafenib, treatment with programmed death-1 (PD-1) checkpoint inhibitors (nivolumab or pembrolizumab) enabled objective response rates ranging between 15% and 20% [ 15 , 16 ]and durable tumor responses. Furthermore, in stage IIIB, IIIC or IV melanoma, adjuvant therapy with nivolumab achieved significantly higher recurrence-free survival rates than adjuvant therapy with ipilimumab [17]. These observations are the basis of an ongoing phase III, randomized, doubleblind study which explores the hypothesis that the adjuvant therapy with nivolumab after curative-intent resection or ablation of HCC, in high-risk patients, may improve recurrence-free survival rates [18].

The median OS observed in the AR group of the present series(28 months) was even higher than those reported by Park et al.(21.4 months) [5], Berger et al. (17.3 months) [4], and Hornstein et al. (14 months) [11]. Because in the present series the percentage of patients with intrahepatic disease at the time of AR (50%)was similar to those observed in the series reported by Park et al.(60%) [5], Ha et al. (42.1%) [8]and Berger et al. (44.7%) [4], the better survival observed in actual series may be explained by the fact that intrahepatic disease was well controlled in all the patients from the AR group. Thus, Ha et al. considered that intrahepatic HCCpersedoes not represent a contraindication for AR,if the liver tumor could be controlled [8]. Furthermore, Poon et al.revealed that aggressive management with combined resection of isolated extrahepatic metastases and re-resection or locoregional therapy for intrahepatic recurrence enabled median survival to 44 months, significantly longer than those achieved by non-surgical therapies addressed to the extrahepatic metastases (10.6 months,P= 0.002) [19]. These results may suggest that the survival after AR for AOM is influenced by the ability to effectively control intrahepatic disease, rather than the presence of intrahepatic tumor itself.

Obviously, the presence of AOM proves a disseminated disease and it is not rationale to consider that a local therapy (like AR)could enable curability. Therefore, it is not a surprising observation that the 3-year PFS was 0% in the AR group, similar to the results reported by other authors (in Asan Medical Center, recurrence rate was 100% at 2 years after AR in patients who underwent previous liver resection for HCC) [8]. By this reason, the guidelines consider that resection of extrahepatic metastases in patient with mHCC is a futile and meaningless intervention, recommending systemic therapy with sorafenib [ 1 , 2 ]. However, it could be hypothesized that the results of systemic therapy could be improved by a better control of the extrahepatic metastases (through a local therapy, e.g. AR). Unfortunately, at present, complete resection of HCC and extrahepatic metastases cannot be associated with systemic therapy, because the health insurance companies do not reimburse such a treatment. This decision is based on the results of STORM trial which did not reveal any survival benefit in patients who received sorafenib after curative resection of the HCC, compared with the patients who underwent resection or ablation alone [14]. However, the situation is different in patients with extrahepatic metastases (that reflects a widespread disease).In such stage of the disease, the intent of the surgical resection of extrahepatic metastases is palliative, aiming to reduce the tumor burden and decrease the risk of further dissemination from the metastatic sites. By this reason, in patients with extrahepatic metastases from HCC, surgical removal of the metastases could be seen as a palliative therapy complementary to sorafenib. Such a combination between surgery and sorafenib has already been considered by some authors who recommended postoperative therapies (such as TACE or sorafenib) in patients who are at high-risk of recurrence after resection of HCC (even in absence of extrahepatic metastases) [20]. Furthermore, in the present series, upon recurrence after AR, the treatment of choice was sorafenib. Thus, in fact,in AR group, the treatment with sorafenib was just postponed for a median 14 months (median PFS in AR group). These arguments represent the premises for future trials aiming to compare the survival rates achieved by extrahepatic metastasectomy associated with postoperative sorafenib vs. metastasectomy alone. Given the promising results achieved by the checkpoint inhibitors in treatment of patients with advanced/metastatic HCCs [ 15 , 16 ], the association between metastasectomy and immunotherapy may also represent a future direction of investigation. Some authors hypothesized that the administration of a checkpoint inhibitor in association with a local therapy (such as TACE, ablation or even resection)may enable a robust tumor-specific immune response by boosting the function of T cells primed by activated antigen presenting cells [21]. This is a consequence of antigen release during local therapies, and subsequent exposure of damage-associated molecular patterns, which can activate antigen presenting cells that have phagocytosed tumor antigens [22].

The present study has some limitations due to its retrospective nature and small sample size. Although the baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar for most parameters, the intent of treatment addressed to the primary tumor was significantly different. By this reason, a major drawback of this study is represented by the significantly lower proportion of curative-intent approaches to the HCC in the SOR group. Consequently, it could be considered that in the SOR group, the primary tumor was less effectively controlled. That may represent a potential explanation for the inferior long-term outcomes achieved by this group. Thus, it could be hypothesized that the intent of the therapy addressed to the primary tumor could induce a bias in the survival outcomes of the two groups, representing a confounding factor. Nevertheless, there are no studies assessing the impact of the primary tumor treatment on long-term outcomes of patients with mHCC. Because the survival rates of patients with disseminated malignancies depend mainly on the ability to control metastases, it is not clear the impact of the primary tumor removal on the survival of patients with metastatic disease. Although the patients in the AR group were more frequent candidates to surgical therapy of the primary tumor, it is less conclusive the initial resectability of HCC, because this study does not evaluate the survival since primary tumor diagnosis. The survival rates reported in this study were calculated since AM development. Moreover, in patients with metastatic disease, irrespective of the primary location, the benefit of primary tumor resection is doubtable, most patients with such an extensive disease receiving only palliative oncologic therapy. For example, in patients with uncomplicated colorectal cancer and unresectable metastases, guidelines do not recommend resection of the primary tumor, because there is no evidence that primary tumor resection would improve survival. Similarly, in patients with mHCC,the guidelines do not recommend resection of the primary tumor,even when this is technically feasible. In one way, the aim of this study is to compare the results of surgery to those achieved by oncologic treatment in patients with mHCC (limited to the adrenal gland). Moreover, as it was mentioned above, both strategies evaluated in this study are considered palliative, and in such therapeutic strategies it is not clear the influence of primary tumor removal on the outcome of patients. However, the effect of this confounding factor cannot be surpassed in this series, and future phase II/III trials are needed to assess whether AR is associated with better survival outcomes than sorafenib therapy, in patients whose primary tumors were treated in a similar way. Another limitation of this study is represented by the small sample size. Although AM represents the third most frequent location of extrahepatic metastases from HCC [ 5 , 6 ], the incidence of AOM is very low, representing 4.6% of the patients with extrahepatic metastases from HCC [5], and 0.25% of all the patients with the diagnosis of HCC [5]; meanwhile, 0.8% of patients who underwent liver resection or LT for HCC developed metachronous AM [6]. By these reasons, this limitation is difficult to be surpassed even in high-volume centers, with none of the series reporting AR for AOM from HCC exceeding 26 patients [ 6 , 8 ]. The only way to overcome this small number of patients might be the performance of a multicentric analysis. Another criticism that could be addressed to this study is represented by the fact that upon progression on sorafenib the patients did not receive regorafenib, cabozantinib or ramucirumab, which are effective treatments for patients who develop progression of disease after sorafenib [23–25]. Due to the fact that the patients included in this study were enrolled until December 2018, and the last two drugs were approved by FDA in 2019 [2],regorafenib was the only second-line agent available at that moment for treating HCC patients whose disease progressed after sorafenib. Unfortunately, the treatment with regorafenib (for patients who develop progression of disease after sorafenib) is not reimbursed by national health-insurance company, so far. Because regorafenib significantly improved OS rates in patients with progression of disease after sorafenib [23], it may be hypothesized that in the current study, OS rates in the SOR group might be prolonged by this second-line therapy. However, a similar OS benefit could have been also achieved in the AR group, because in both groups there were 3 (out of 8) patients who received sorafenib after progression of disease with sorafenib [26]. The other patients in the SOR group who had a poor performance status that precluded sorafenib (and received best supportive care), most probably would not tolerate regorafenib. Thus, it is unlikely that the difference in OS rates between the two groups could have been influenced by the use of regorafenib. Although this study has major drawbacks and cannot draw definitive conclusions, it has the merit to report results that may support the initiation of future phase II/III trials to assess the benefit of AR in patients with AOM from HCC.

Until such larger and controlled trials are available, the results of the present study could not be extrapolated to all the patients presenting extrahepatic metastases from HCC, remaining limited to a carefully selected population (with well-preserved liver function and controlled intrahepatic tumor) presenting AOM from HCC. In such patients, AR was associated with significantly higher PFS and OS rates than systemic therapy with sorafenib.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sorin T Alexandrescu:Conceptualization, Writing - original draft.Adina E Croitoru:Conceptualization, Writing - original draft.Razvan T Grigorie:Data curation.Dana R Tomescu:Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.Gabriela Droc:Formal analysis, Writing- original draft.Mugur C Grasu:Formal analysis.Irinel Popescu:Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania (59425/3.12.2019).

Competing interest

Adina E Croitoru, Mugur C Grasu, and Irinel Popescu have received speaker honorarium from Bayer Company, for topics that were not related to the work under consideration.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Liver transplantation and BCLC classification: Limitations impede optimum treatment

- Do the existing staging systems for primary liver cancer apply to combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma?

- Overlap of concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune diseases is associated with milder disease severity of newly diagnosed autoimmune hepatitis

- Integrating transcriptomes and somatic mutations to identify RNA methylation regulators as a prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma

- The utility of two-dimensional shear wave elastography and texture analysis for monitoring liver fibrosis in rat model

- Impact of referral pattern and timing of repair on surgical outcome after reconstruction of post-cholecystectomy bile duct injury: A multicenter study