The Development and Practice of Audio Description in Hong Kong SAR, China

2019-05-12DawningLEUNG

Dawning LEUNG

Audio Description Association (Hong Kong)

Abstract Audio description (AD) is a form of audiovisual translation that translates visual and unidentifiable sound elements into verbal descriptions. One of its major functions is to make audiovisual materials accessible to the blind and partially sighted. AD development and practice in Western countries and regions have been reported widely over the years, while very limited information regarding these areas in a Chinese context can be found. This paper compares AD provision across various Western and Asian countries and regions. It then presents the recent development and practice of AD in Hong Kong SAR, China. It includes an introduction of the Audio Description Association (Hong Kong) which raises the profile of AD in the territory and describes two forms of AD services: AD in museums and AD for lion dance performances. The current practice of AD production for films in Hong Kong SAR, China will also be discussed.

Keywords: audio description, accessibility, audiovisual translation, blind and visually impaired, audio description practice, audio description production

1. Introduction

Audio description (AD) is a professional practice that consists of translating visual and sound elements in audiovisual programmes into verbal elements, thus making these materials accessible to users with visual impairments. It has been a major area of interest within the field of audiovisual translation studies in recent years and a considerable amount of literature has been published on AD development and practice in Western countries and regions. However, when it comes to the Asian world, the literature on these aspects is very limited.

AD has been in use for more than 25 years in some of the countries and regions of the Western world and various countries and regions have passed legislation regulating the provision of AD, especially by government-owned TV channels. Various guidelines and style books have also been drafted for regulating the production of professional AD across Europe. For example, in the UK, the 1996 Broadcasting Act imposes a 10% requirement for audio described programmes on digital terrestrial TV; and in Spain, the White Paper of the Spanish audiovisual law Ley General Audiovisual mandates that governmentowned channels provide AD for at least 10% of their programmes by 2015 (Díaz-Cintas, 2010; López Vera & Franciso, 2006, p. 148). Meanwhile, in the USA, the 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act enforces a requirement of four hours of described programmes per week on nine TV channels (American Council of the Blind, n.d.).

In the Asian world, the provision of AD has been part of the socio-cultural life of places like Japan and South Korea since the beginning of the 1970s and the 2000s, and media access regulations have also been introduced in these regions. Regular provision of AD on TV can be found in Japan and South Korea. By contrast, the development of AD in Chinese mainland and Hong Kong SAR began only in the 2010s and is at a very early stage, while the regular provision of AD on TV is still non-existent.

2. Comparison of AD provision across countries and regions

Some countries and regions have a much longer history than others in the provision of AD for audiovisual programmes, with some of their pioneering experiences having taken place over 35 years ago. Japan started the provision of AD on TV back in the 1980s (ITC, 2000, p. 5; Yeung, 2007, p. 232), while the UK, USA, Spain, and Germany did so in the 1990s. South Korea started its access services on TV in the early 2000s (Chao, 2009, pp. 19-20; The League for Persons with Disabilities, 2012). In some countries and regions there exists legislation that regulates the provision of media access, both in the case of Subtitling for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (SDH) and AD, and the percentage requirements of the former are always greater than in the case of AD. Some of the legislative acts concerning AD provision on the TV have set a compulsory AD quota of around 10% of their on-air time, such as in the case of the most watched TV channels in the UK and Spain. In addition to these legislative measures, some TV broadcasters in the UK and Germany have led with voluntary self-commitment, providing 20% of their programming with AD (RNIB, n.d.; RNIB, 2016). On a wider level, on 6 November 2018, the European Council adopted the revisedAudiovisual Media Services Directivegoverning “EU-wide coordination of national legislation on all audiovisual media, both traditional TV broadcasts and on-demand services” (European Commission, 2018a). Article 7 suggests that governments of member states must encourage media service providers under their jurisdiction to make audiovisual products accessible to people with a visual disability by audio description (ADLAB, 2012, p. 26; European Commission, 2018b). In countries and regions like South Korea, the promotion of access services is instigated from above and the Korean Communications Commission provides full or partial funding for making TV programmes accessible for the blind and the partially sighted. As for the Chinese speaking world, there is no official media access legislation nor is there any regular provision of AD on TV.

In addition to the provision of AD for TV programmes, most countries and regions also offer AD services for films that are distributed on DVD or in the cinema. So far, in the UK and the USA, between 550 and 1100 DVD titles include AD soundtracks while in Germany over 130 titles on DVD come accompanied with AD (ADLAB, 2012, p. 26; American Council of the Blind, 2016; Your Local Cinema.com, n.d.). In the specific instance of cinema distribution and exhibition, funding has been offered by some governments to support the installation of AD equipment in cinema theatres, as in the cases of the UK and Australia. The UK Film Council offered partial funding for installation in 78 cinemas (World Blind Union, 2011, p. 36, 2016, p. 38), while a one-off grant from the Federal Government in Australia supported 12 cinemas (Mikul, 2010, p. 4). Although AD for films is available in Chinese speaking countries and regions, there is virtually no information available that could reveal to what extent AD is provided in cinemas or commercially distributed on DVD.

Different from the countries and regions that have experienced a more mature development in the provision of AD, Hong Kong SAR, China has a much shorter history that can be traced back to the year 2011. In this short, though rather productive period of time, AD has made its appearance in the cinema exhibition of films and, at the time, there is still no regular AD provision on TV. As far as the regulation of AD requirements is concerned, no legislation has been passed or imposed on the broadcasting or film industries. Recent AD developments and current practice of AD production for films in Hong Kong SAR, China will be discussed.

3. Recent developments and practice of AD in Hong Kong SAR, China

Awareness of the particular needs of visually impaired people as regards their access to the audiovisual media began to increase in Hong Kong SAR, China only in 2009. It was at that time that AD services started to be introduced by local NGOs to meet the needs of visually impaired people and to help them better integrate into society. As shown below, in the discussion of the different types of AD provision in Hong Kong, the Audio Description Association (Hong Kong) has played a key role in the recent developments of AD practices in the city.

3.1 Audio Description Association (Hong Kong)

Founded in 2015, the Audio Description Association (Hong Kong) (AuDeAHK) (www.audeahk.org.hk) is a non-governmental organisation that works to raise the standards and profile of AD in Hong Kong SAR, China while offering professional AD training and AD services for the community. Since the offer of AD is very limited in Hong Kong the AuDeAHK takes a leading role in the provision of training and public education in the city and in other neighbouring regions such as Macao and Guangzhou. AuDeAHK offers two forms of professional AD training: certificate courses and workshops. Each course or workshop has a focus, for example, basic AD skills, AD for films, and AD for museum exhibitions. Other than offering AD public education sessions and AD training, AuDeAHK also provides numerous professional AD services, including AD script writing, AD production (i.e. pre-recorded AD/AD sound tracks), AD service consultation, and research on AD users (reception studies and AD activity/event evaluations and analysis), as well as end-to-end AD services from preparation (e.g. site visit) and research through AD script writing to AD quality control and AD delivery. As an access service provider, AuDeAHK offers a vast array of AD services, including AD for films, TV programmes, short videos, performing arts, visual arts, museum exhibitions, outdoor activities (e.g. Stargaze Camp for All), sports (e.g. the World Cup 2018), and events, such as lion dance performances, film festivals, and music awards presentations ceremonies (Commercial Radio Hong Kong, 2018; Etnet, 2018; HK01, 2018; i-CABLE news, 2018; Metro Broadcast, 2017a, 2017b; Ming Pao, 2017, 2018; Sing Tao Daily, 2019; Sky Post, 2018). These services are especially provided to organisations for the blind and partially sighted (such as Hong Kong Society for the Blind, HKSB) and to visually impaired individuals upon request. This encourages social inclusion and increases accessibility for the visually impaired to art, cultural, sports, and recreational activities. In addition, AuDeAHK has successfully secured government funding for the development of several social innovation initiatives: Audio Description Services for Museums (SIE Fund, 2017), Audio Description Services for Outdoor Activities (SIE Fund, 2018a) and Film Audio Description Services (SIE Fund, 2018b). To ensure that its AD services better fulfil the needs of end users, AuDeAHK has created a job position ‘Audio Description Quality Evaluators’ (口述影像质量评估员) and recruited blind and partially sighted people who are frequent AD users to serve as evaluators, so that they can be involved in AD production through contributing to the evaluation of the quality of the AD and providing constructive feedback that can be used for its improvement after trial runs (Leung, 2018; SIE Fund, 2017).

3.2 AD in museums

During a nine-month project, supported by the Hong Kong SAR Government’s Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship Development Fund (SIE Fund), the AuDeAHK was able back in 2017 to launch an initiative called ‘Audio Description Services for Museums’, with the main objective to increase visually impaired people’s participation and interaction in society (SIE Fund, 2017). The major beneficiaries are non-governmental organisations serving the blind and partially sighted. Live described tours are provided for permanent and special exhibitions at local museums, such as the special exhibition ‘Eternal Life — Exploring Ancient Egypt’ hosted at Hong Kong Science Museum, and one entitled ‘Miles upon Miles: World Heritage along the Silk Road’ celebrated at the Hong Kong Museum of History. Other permanent and special exhibitions have also been organised at the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences. During the tour of these exhibitions, live AD is delivered via headsets. To complement the description, tactile props and diagrams are also provided to enhance the experience and assist the comprehension of the blind and partially sighted participants. For the exhibition on ancient Egypt, for instance, ten tactile props and seven tactile diagrams were prepared. Tactile props such as 6-inch mummies together with coffins were used when describing Nestawedjat’s mummy (内斯达华狄特的木乃伊) and her three coffins. Other tactile props included dummies of canopic jars and small figures of the Egyptian god Anubis and scarab beetles among others. Tactile diagrams were also provided for the Stela of Neferabu (尼弗拉布石碑) and the Eye of Horus (the protective wedjat 荷露斯之眼) (Leung, 2018; Ming Pao, 2017). Another example is for the exhibition at Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences. Besides delivering live AD via headsets, more than 15 tactile props were tailor-made such as the Schimmelbusch Mask (施氏麻醉面罩), and purchased for this tour, including 3D human body models, medical tools, and laboratory containers. Tactile props were used throughout the tour to complement the description (HK01, 2018; i-CABLE News, 2018; Leung, 2018). Before the official launch of the described tours for museums, visually impaired Audio Description Quality Evaluators were recruited to evaluate the tours during trial runs. They provided end user feedback on the audio descriptions, tactile props, and tactile diagrams. (Leung, 2018; Metro Broadcast, 2017b; SIE Fund, 2017)

3.3 AD for lion dance performances

In recent years, AuDeAHK has been invited to provide AD for the lion dance performance at Spring Festival dinner, which is a common gathering with relatives, friends or co-workers after the Chinese New Year. The lion dance is a unique live traditional Chinese performance that is popular not only in Chinese areas but also all over the world. It is the most common performance during the Chinese New Year celebrations in Asia and in Chinatowns throughout the world, and it has been featured in a wide range ofkung fufilms. Lion dance performances can take place in a restaurant, a ballroom or in the street. Those in the former locations have a set routine with an essential climax known as 采青, pronounced as ‘choi cheng’ in Cantonese and as ‘cai qing’ in Putonghua, which literally means ‘pluck the greens/lettuce’. The lion dancers must rehearse the performance beforehand because of the limited space provided in the actual venues. In contrast, street performers can move freely for their show and may not include the ‘choi cheng’ routine. In the street, the pace of the performance is slower, and there is usually more space, such as in a parade. When a describer knows that s/he is going to deliver the AD for indoor performance, it is common that s/he can view the rehearsal in advance and make notes of some of the key movements and actions in order to better prepare for the production of the AD script. The describer should develop some notes to describe the set routine, i.e. the beginning, the climax, and the end of the performance. S/he should also familiarise herself/himself with this kind of performance to be able to use the appropriate register and terminology freely in context. Having extensive and detailed knowledge of this traditional dance will be helpful in case the performers make impromptu changes to certain movements and actions.

The martial arts-related performance usually lasts for 10 to 12 minutes. Responding to unique drumbeats, two performers (one at the head and the other at the tail of the lion), wearing tailor-made costumes, mimic movements of a lion/cat. To describe a lion dance performance, the describer will need first to depict the lion and then describe the eye-dotting ceremony, a symbol of life-giving. The lion’s forehead, eyes (left, then right), nose, mouth, ears, horn, back of the body, and tail will be dotted. In these early stages, the describer should focus on the awakening of the lion. Next, the lion starts its own performance, bowing, walking, looking for food, eating, playing, jumping, lying low, and rolling. The highlight of the performance is when the lion starts to ‘choi cheng’, a traditional custom that represents good luck. The lion will chew the lettuce and spit it out, which represents the spreading of wealth and prosperity. Finally, the lion will bow again. Throughout the performance, a Big Head Buddha carrying a rattan fan will lead the lion from the starting point to the place of ‘choi cheng’, and a drum, gongs, and cymbals will be played for the performers to follow. During the whole event, the lion will also interact with the audience. Non-governmental organisations for the blind and partially sighted, such as HKSB, are in favour of the provision of AD for lion dances to entertain all of the staff, including those with visual impairments, at the Spring Festival dinner to achieve social inclusion. (Leung, 2015; Leung, 2018; Media Access Australia, 2015)

4. The current practice of AD production for films

Since 2010, 21 Chinese films with AD have become available on DVD. Some of them offer both Cantonese and Mandarin AD soundtracks, for example,A Simple Life(《桃姐》) (Lee, Hui, Chan, & Hui, 2012),Blind Detective(《盲探》) (To, 2013), andLittle Big Master(《五个小孩的校长》) (Chan, Lam, Tong, & Kwan, 2015) (Leung, 2018). Since 2018, the provision of AD can be found in six local cinemas equipped with AD systems (MCL Cinemas, n.d.; The Metroplex, 2018; UA Cinemas, n.d.). Visually impaired audiences can hire a receiver at the cinema and listen to the AD sound track via headsets inside the cinema theatre.

Different modes of audiovisual translation have been adopted when encountering foreign languages in local Cantonese films. The filmStill Human(《沦落人》) (Chan & Chan, 2018) is a good example. It is a story about a paralyzed Hong Kong man in a wheelchair and his new Filipino domestic worker, and several languages including Cantonese, English, and Tagalog are used. I am the audio describer that has provided pre-recorded AD for this film. Cantonese audio subtitling has been adopted to voice over dialogue in English and Tagalog during AD recording. The AD sound track has been played in four local cinemas. (Sing Tao Daily, 2019)

The process of AD production for films will be discussed below. The process consists of five stages.

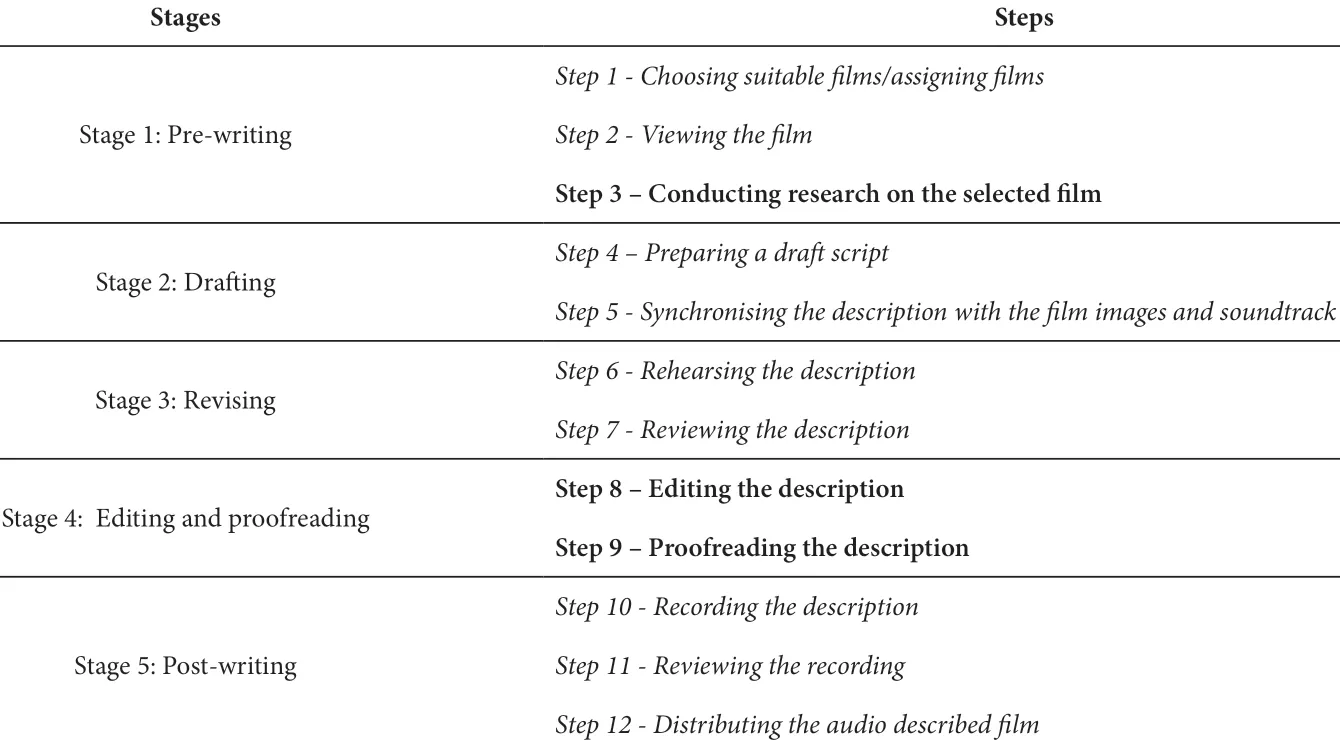

Hernández-Bartolomé and Mendiluce-Cabrera (2004, pp. 270-271) list nine steps in the production and distribution of AD for films: (1) choosing suitable films, (2) viewing the film, (3) preparing a draft script, (4) synchronising the description with the film images and soundtrack, (5) rehearsing the description, (6) reviewing the description, (7) recording the description, (8) reviewing the recording, and (9) distributing the audio described film.

AD script writing can be considered to share many similarities with the writing process experienced in language teaching and learning. Langan (2008) divides the writing process into four main stages, namely (1) prewriting, (2) writing the first draft, (3) revising and (4) editing. Inspired by Langan’s (ibid.) work, according to the nature of the various stages, and based on the practical experience that I have accumulated over the years as a practising audio describer in Hong Kong SAR, China, I have merged the above mentioned nine steps (Hernández-Bartolomé & Mendiluce-Cabrera, 2004) together with three newly added phases — namely conducting research on the selected film, editing the description, and proofreading the description, to come up with a total of 12 steps (Leung, 2018). In addition, further to the four main stages of the writing process suggested by Langan (2008), a new main stage (post-writing) has been added to the AD production process because, on occasion, the description will be recorded and distributed in DVD format. The three new steps proposed on the basis of my professional experience (in bold) have all been grouped under five main umbrella stages: (1) pre-writing, (2) drafting, (3) revising, (4) editing/ proofreading, and (5) post-writing, as illustrated in Table 1 below:

Table 1. Five stages of AD production for films (Leung, 2018, p.48)

In what follows, these stages are discussed in detail using the Hong Kong socio-cultural context as the case study.

Stage 1: Pre-writing

The pre-writing stage refers to any preparations that need to be taken care of before the actual AD script writing can take place. There are three steps within this stage.

Step 1-Choosing suitable films/assigning films. In Hong Kong SAR, China, AD is not provided for broadcast productions and the provision for film screening sessions in cinemas is rather limited and usually done on a voluntary basis. Therefore, on most occasions, it is the volunteers themselves who get to choose the films that they would like to audio describe. However, when the service is requested by a film production company or an organisation, the company will decide and assign which film is to be described. In the decision of what productions to audio describe, it has to be kept in mind that not all the films are equally suitable for AD. Indeed, as highlighted by authors like Hernández-Bartolomé and Mendiluce-Cabrera (2004, p. 270), some films have “more action than dialogue, and the description would be almost continuous” with not much interference from the original; whereas in the case of other productions, in which the dialogue exchanges are profuse, users may find the AD “tiring to listen to, even irritating”. Given the limited availability of films with AD in Hong Kong SAR, China, it should not prove too difficult to find productions that lend themselves easily to be audio described.

Step 2-Viewing the film. After a film has been selected, the recommendation is that audio describers should watch the whole film at least once to gain an overall idea of the characters and the plot. They should get first-hand experience, remember the mood and feelings of the film in their first watch, and try to re-create that mood when writing the AD script. They should then watch it for a second time in order to spot all the silent gaps in the dialogue that are suitable for inserting the AD information. To reinforce their empathy towards the target audience, Hernández-Bartolomé and Mendiluce-Cabrera (ibid., p. 270) suggest that the audio describer could use a special technique and “view the film without the picture or use simspecs (a pair of glasses that simulate visual impairments)” so that they can put themselves in the shoes of the visually impaired audience.

Step 3 – Conducting research on the selected film. Conducting background research on the selected film to be audio described is highly beneficial for preparing a precise and accurate description of some of the visual elements shown in the films. For example, when describingKung fufilms, the describers should conduct extensive research about martial arts and be able to identify the various moves and techniques, so that they can use the accurate lexicon to draft a more exciting and appropriate description of the fight scenes.

Stage 2: Drafting

The drafting stage implies the writing of the first AD script and consists of two steps.

Step 4 – Preparing a draft script. While identifying suitable gaps for the overlaying of the AD, describers may want to start drafting the AD script as well. They should decide what, when, how, and how much to describe. According to the AD guidelines prepared by Ofcom (2015, p. 20) in the UK, which visual elements to describe greatly depends on the extent to which they are relevant to the storyline, and the AD “should describe characters, locations, time and circumstances, any sounds that are not readily identifiable, on-screen action, and on-screen information”. As for when to incorporate the AD, a study carried out by Chmiel and Mazur (as cited in ADLAB, 2012, p. 50) in Poland, reported that most AD consumers found that the major barrier for them to receiving the AD is when it overlaps with dialogue. Hence, Puigdomènech, Matamala, and Orero (2010, p. 40) advise that describers should insert descriptions “when there is no dialogue and always [try] to anticipate the action”, a piece of advice that is also found in Hyks (2005, p. 6). As far as possible, AD should not overlap with sound effects or song lyrics either, unless it is extremely necessary (Ofcom, 2015, p. 21).

Two contrasting views of AD styles, namely objective vs. interpretative, have generated heated debate among scholars and professionals. In this respect, the USA approach towards AD is said to be more objective than that practised in Europe (Audio Description Coalition 2009, p. 2), and so, for instance, when describing emotions, the USA solution may stay on the descriptive level and state ‘tears are pouring out of his eyes’ or ‘there is a big smile on her face’. In contrast, other professionals prefer to opt for a more interpretative approach and use adjectives such as ‘sad’ or ‘happy’ to describe the same emotions (Puigdomènech et al., 2010, p. 40). Based on the findings of her reception study with people with visual impairment, Leung (2018) suggests that “The use of emotive adjectives should be given priority instead of merely describing facial expressions. ... If time permits, emotive adjectives combined with the description of facial expressions and/or gestures could be used as in, for example, ‘he frowns, feeling strange’ and ‘she shrugs, a bit helpless’.”

Another aspect that sparks off an intense debate in academic exchanges is whether cinematic language and terminology should be used as part of the AD discourse or not. As pointed out by Orero (2012), filmic language has great importance in the creation of the original production since it is the primary fabric for film directors to produce their oeuvre. Indeed, “a film has a paradigmatic connotation when the director has chosen specific cinematic aids to portray an effect, such as a camera angle or move, a colour filter, etc.” (ibid., p. 18), which may be missed altogether by the visually impaired audience if this information is not somewhat conveyed in the AD. The traditional approach has been to avoid any reference in the AD to the technical artifice behind a film, and many guidelines, such as the ones compiled by Ofcom (2015, p. 21), discourage the use of filmic terms. Nonetheless, and against this traditional conception, two recent studies by Fryer and Freeman (2012, p. 412) and by Leung (2018, p. 221) reveal that the majority of the visually impaired hold a positive opinion when it comes to the use of cinematic terminology in the AD.

As there are no standard guidelines in the Chinese context, the current situation in Hong Kong SAR, China is rather fluid and different describers adopt their own AD styles, be it objective or interpretative, in which cinematic terminology can be present or absent. In this sense, it seems imperative that more reception studies on AD style should be carried out in order to elicit the preferences of end users as a basis for the compilation of a set of AD standards targeted towards the visually impaired population in Hong Kong SAR, China.

Since describers should try their very best to assure that their descriptions fit in the silent gaps found between the dialogue, they should be fully aware of the importance of time restrictions, and only plotrelated images should be described to assist the end users in following the storyline. The Spanish Standard UNE 153020 also suggests that describers “must avoid causing the visually impaired listener to become tired due to saturation of information or anxiety due to a lack thereof” (Rai, Greening, & Petré, 2010, p. 16). In other words, describers should not fill all the gaps (Cronin & King, 1990) and some pauses should be respected, if possible, so that the audience does not feel overwhelmed by the amount of information they are receiving. Similarly, describers should not leave long empty breaks in their description because the visually impaired viewers may think that there has been a technical problem in the delivery of the AD or be anxious to know what is happening on the screen.

Step 5-Synchronising the description. When drafting the AD, describers should also consider whether the AD inserts are well synchronised with the moving images on screen. Authors like Hernández-Bartolomé and Mendiluce-Cabrera (2004, p. 270) consider the degree of synchronisation to be no less than utopian, which is “seldom achieved” since as experience suggests, “descriptions tend to appear just two seconds before the images”; a rather categorical assertion by the authors. Indeed, although it is true that achieving full synchronisation is difficult, such an argument that the descriptions appear ‘just two seconds, before the images’ is too dogmatic and bound not to be true in all cases. In fact, on occasion, the description may even come slightly later than the images and the authors seem to be aware of this circumstance when they explicitly acknowledge that, “Thrillers should receive special treatment, since the description could be delayed after the action in order not to anticipate events and destroy the film’s atmosphere” (ibid., p. 270).

Stage 3: Revising

The revising stage covers the two steps that should be carried out after the AD draft has been completed.

Step 6-Rehearsing the description. Orally rehearsing the AD script is a crucial task, especially in the Hong Kong context where the majority of AD provision for films is done live. When making the AD recording, describers can retake the same line as many times as they deem necessary. However, in a live AD screening, the describer is involved in the continuous delivery of the AD from the beginning to the end of the film, and there is no break in between. When a human error occurs, such as a slip of the tongue, a mispronunciation or a grammatical/syntactical mistake, there may not be a chance to rectify it. Sometimes, important information may be lost in this way. Conducting sufficient rehearsals before the actual event can help to reduce the chance of making such mistakes because the describer is more familiar with the AD script. One of the potential drawbacks of not rehearsing the script is that describers may not be aware that a given section of the description is too long to fit in a particular gap. Therefore, describers should run through the AD, out loud if possible, at least once in order to make sure that they have enough time to read aloud all the descriptions that need to be inserted within the silent gaps in the dialogue, particularly the short ones.

Step 7-Reviewing the description. Describers are advised to check whether there are any mistakes or inconsistencies in the AD. The accuracy of the AD is extremely important because a misdescription may result in confusion and miscomprehension of the plot among the audience. One of the drawbacks of not reviewing the AD before it is recorded is that some inconsistencies that may have cropped up in critical moments, especially in fast-changing scenes, may be overlooked and end up making it into the final AD version. In this part of the process, teamwork can be one of the solutions to avoid these potential mishaps and having a sighted script quality supervisor working in close collaboration with a blind description quality specialist can improve the chances of spotting any mistakes and, consequently, of boosting the quality of the end product.

Stage 4: Editing and proofreading

After revising the first draft, two more steps should be taken to finalise the AD script.

Step 8 – Editing the description. Once the first draft is considered finished, describers should polish the AD by creating more succinct descriptions and using targeted terminology where appropriate, as the use of accurate vocabulary can “keep description lively and brief” (Yeung, 2007, p. 234). Any unnecessary words should be deleted to save time and the tone and style of the AD should be checked so as to make sure that they fit the mood of the film. In this regard, the use of more elegant wording is recommended if the AD is to accompany a literary film, whereas some slang could be used if the film is about pop culture or youth delinquency. Attention should also be paid to the “moods and feelings of the film if [the describers] aim at creating comparable experiences for the unsighted as that experienced by the sighted” (Chao, as cited in Yeung, 2007, p. 241). Effective use of punctuation is also highly recommended as it can help the end users to understand the description more efficiently.

Step 9 – Proofreading the description. Having an extra pair of eyes to check one’s work is always a good way to spot any mistakes, inconsistencies or potential areas for improvement, and describers should share their final work with other describers to achieve this goal. By correcting errors or receiving suggestions for improvement, confusion can be avoided, and good professional practice can be enhanced among describers. Indeed, for professionals like Dosch and Benecke (2004) the ideal professional environment is the one that allows for collaboration between two colleagues, one sighted and the other visually impaired so that they can advise and help each other to produce the most appropriate audio description possible.

Stage 5: Post-writing

Once the AD script is considered final, there are still three more steps to be taken. As mentioned previously, usually only live AD is available in Hong Kong SAR, China for audiovisual programmes such as films and TV programmes. This means that only on very few occasions is the AD pre-recorded, as highlighted in the brief discussion below.

Step 10-Recording the description. In the particular case of Hong Kong of China SAR, the person in charge of writing and revising the AD script is also responsible for its live delivery. However, if the AD script has been produced to be recorded rather than delivered live, then it is more common to hire a professional voice talent to do the recording of the AD in the studio.

At present, the practice of recording AD is not fully standardised, and it varies greatly across productions because the actual sound mixing is usually done in a studio hired by the different film production companies that own the film to be described. As a result, instances can be found of productions in which the sound is recorded at a lower volume than the original version, sometimes higher, and on other occasions it is equalised. Further research into the technical aspects of AD will be necessary to reach a more detailed account of this professional practice.

Step 11-Reviewing the recording. Ideal practice includes conducting a final check of the recorded AD to ensure the best technical quality. It is suggested that a different person from the voice talent should review the recording. To date, in Hong Kong SAR, China, only the AD recording of certain films has actually undergone review where the process was conducted by a second person. In these cases, the reviewer checked whether there were any missing or misplaced AD items (i.e. discrete insertions of AD narration into the original soundtrack) after sound mixing. In most cases, this step regarding the technical production of AD for films in Hong Kong SAR, China is unknown by most describers.

Step 12-Distributing the audio described films. At the time when this research was being conducted, pre-recorded AD was mainly found on DVDs and no described films had been broadcast on television, hence the emphasis on the former. In Hong Kong SAR, China, only 21 DVDs of commercial films with AD in Cantonese have been made available on the market so far. In 2013, a documentary entitledA Wallless World IV, produced by the public broadcaster Radio Television Hong Kong was broadcast on TV without the provision of AD (Yu, & Chan, 2013). Months later, and due to the level of interest it raised, the documentary was made available with AD and has also been freely distributed on DVD. The DVD copies of this documentary are not for sale and some are kept in various public libraries in the city whereas others have found their way to some of the local NGOs working with people with visual impairments, such as the Hong Kong Society for the Blind.

5. Conclusion

Although the provision of AD in Hong Kong SAR, China is still far less developed, it is also true that Hong Kong SAR has been playing a pioneering role in the Chinese speaking world as far as AD is concerned. From a quantitative perspective, Hong Kong has witnessed the production of AD soundtracks in Chinese, including both Cantonese and Mandarin Chinese, of more than 21 film titles on DVD, which serve not only viewers in Hong Kong, but also those in other parts of China, thus being the very first film titles that serve a wide spectrum of Chinese-speaking communities. In addition, the provision of pre-recorded AD is now available in six cinemas that have been equipped with AD systems, which means that more visually impaired people can be served with the help of technology, and these audiences are better able to go to the cinema according to their own preferences, be it the time or venue.

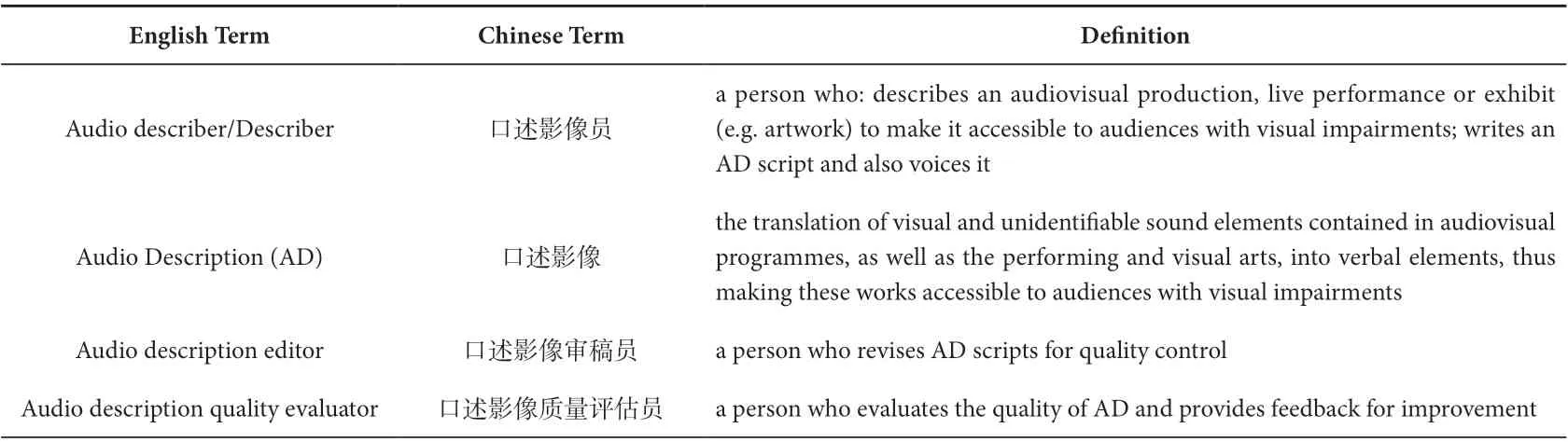

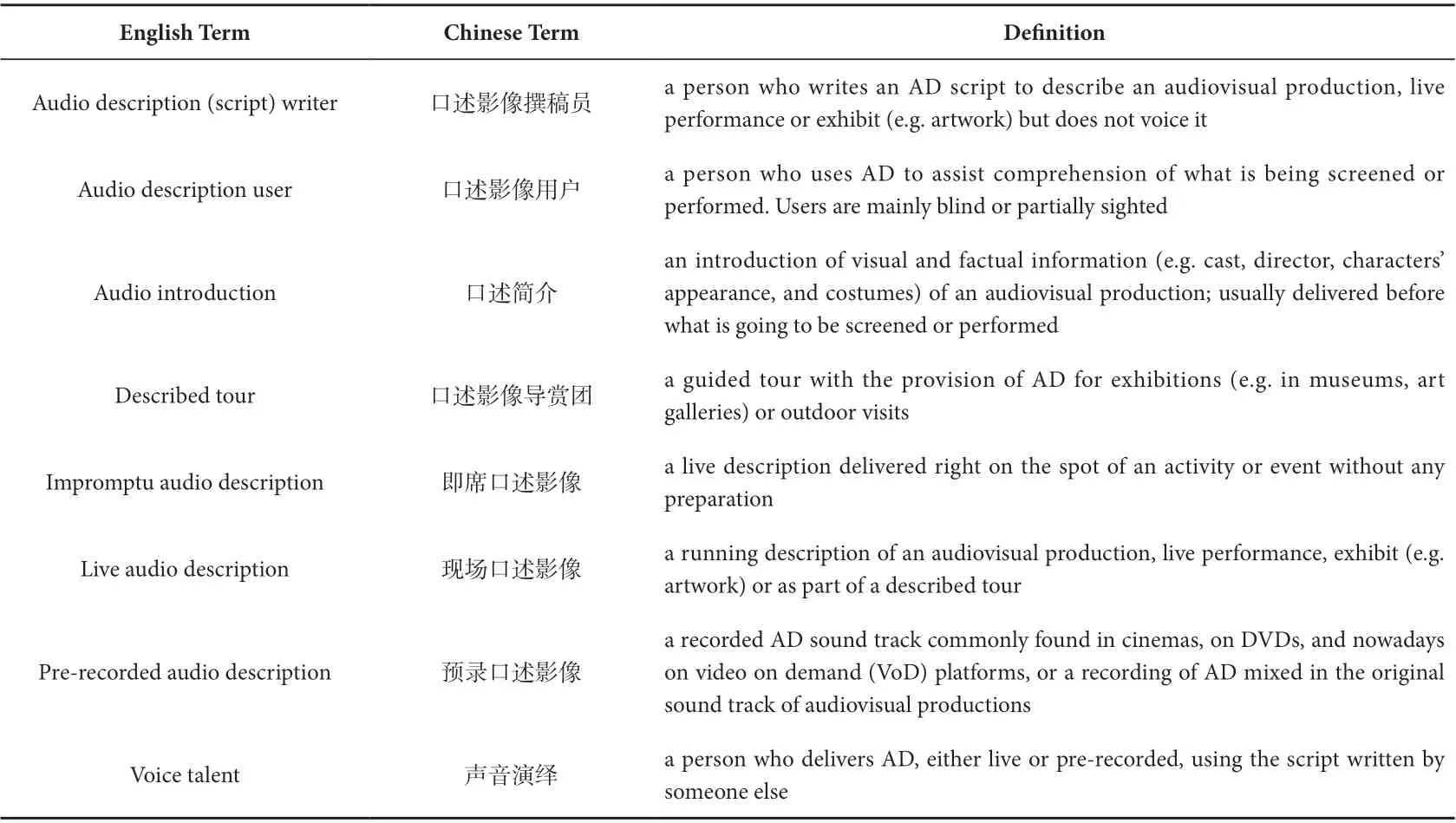

‘Audio Description’ is more than an access service; it is an essential tool for people with visual impairment to enjoy their basic human rights. It helps them to have equal opportunities to gain access to the media and to other arts, cultural, and sports activities just like their visually-able counterparts. The profile of this profession should be raised more widely in Chinese academia, and audio describers should receive proper training before serving the community. To foster the developments of AD in the Chinese world, the use of AD-related terminologies in Chinese should be consistent. Table 2 shows a list of these terminologies. Taking into account the situation of AD in various countries and regions around the world, more research investigating the provision and practice of AD should be conducted in a Chinese context. Research results may serve as a reference for the Hong Kong SAR government and other Chinese-speaking regions, informing the future development of AD in the Chinese world. A set of professional guidelines and best practice should be prepared for practitioners in Chinese AD.

Table 2. English-Chinese glossary of terms related to AD (Leung, 2018, p. 338-9)

to be continued

Table 2. continued

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

翻译界的其它文章

- A Sociological Investigation of Digitally Born Non-Professional Subtitling in China

- A Shift in Audience Preference From Subtitling to Dubbing?—A Case of Cinema in Hong Kong SAR, China

- Omission of Subject “I” in Subtitling: A Corpus Review of Audiovisual Works

- The Subtitling of Swearing in Criminal (2016) From English Into Chinese: A Multimodal Perspective

- Identity Construction of AVT Professionals in the Age of Non-Professionalism: A Self-Reflective Case Study of CCTV-4 Program Subtitling

- Constraints and Challenges in Subtitling Chinese Films Into English