A Shift in Audience Preference From Subtitling to Dubbing?—A Case of Cinema in Hong Kong SAR, China

2019-05-12KitYuWONG

Kit Yu WONG

University of Auckland

Abstract With the advancement of digital technology and the evolution of audience tastes, the traditional mapping between subtitling and dubbing is no longer drawn in black and white terms. By using a corpus of the data of imported films in Hong Kong SAR, China, this study attempts to validate the shift in audience preference from subtitling to dubbing and examine the influencing factors of the shift. The findings of the research confirm the occurrence of the shift and suggest that it can be categorised into three phases. Each phase is affected by different factors that can be roughly classified into several aspects, including economy, ideology, authenticity, and personal preference.

Keywords: audiovisual translation, subtitling, dubbing, audience preference

1. Introduction

This study is located within the field of research in Audiovisual Translation (AVT), which is a relatively new form of translation that has recently gained its own ground in the field of Translation Studies (TS). Today, AVT is defined as a mode of translation that encompasses both well-established and new groundbreaking linguistic and semiotic transfers for audiovisual texts, either interlingually or intralingually (Chaume, 2013). There are three main translation modes in AVT—subtitling, revoicing, and accessibility modes, as Pérez-González (2009) suggests. Subtitling is a translation practice that consists of “presenting a written text, generally on the lower part of the screen, that endeavours to recount the original dialogue of the speakers, as well as the discursive elements that appear in the image […] and the information that is contained on the soundtrack” (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007, p. 8). It is also defined as a diagonal translation by Gottlieb (1994) since spoken language is rendered to written language. In contrast, revoicing is a generic term comprised of several translation practices that involve the rendition of spoken language to spoken language, including simultaneous interpreting, free commentary, narration voice-over, and (lipsynchronised) dubbing (Pérez-González, 2009). For the accessibility modes, there are a few methods to make media content accessible for visually and aurally-impaired viewers, such as audio-description and audio-subtitling, subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing, live subtitling, and sign language interpreting (Remael, 2012).

Among the translation modes of AVT mentioned above, subtitling and dubbing are the most commonly adopted practices for translating films. Dubbing “consists of replacing the original track of a film’s […] source language dialogues with another track on which translated dialogues have been recorded in the target language” (Chaume, 2012, p. 1). In a narrow sense and in this study, dubbing refers to lip-synchronised (lip-sync) dubbing, for which the translated dialogues are performed by dubbing actors to recreate the dynamics of the original soundtrack by paying special attention to delivery pace and lip movements (Luyken, Herbst, Langham-Brown, Reid, & Spinhof, 1991). From the definitions of subtitling and dubbing, it is obvious that they are two completely different approaches to translating films. Each of them possesses unique features that trigger their opposition and spark debate accordingly. In fact, the debate on the choice between subtitling and dubbing arose as early as the emerging of research on the two modes in the 1950s (e.g. Zambuto, 1954). Different countries or regions show different preferences. Western countries were traditionally divided into subtitling countries (e.g. Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Portugal and Sweden) and dubbing countries (e.g. France, Germany, Italy and Spain) (Chaume, 2012; Koolstra, Peeters, & Spinhof, 2002). The UK and Ireland were rare examples where the application of subtitling and dubbing took place on a fifty-fifty basis (Kilborn, 1993). Hence, it is considered that subtitling is predominantly employed in smaller countries where viewers comprise more restricted markets, whereas dubbing is preferred in larger and more affluent countries where high box office returns can be expected (Szarkowska, 2005). However, this deduction oversimplifies real-world situations. In countries that traditionally prefer subtitling, such as Greece, dubbing is extensively adopted for audiovisual materials targeting children (Karamitroglou, 2000). Meanwhile, subtitling is also gaining its popularity among younger viewers in countries traditionally disposed towards dubbing, such as Spain (Perego, Laskowska et al., 2016). Additionally, Danan (1991) argues that dubbing in larger countries is beyond economic considerations, in which it is “an assertion of the supremacy of the national language and its unchallenged political, economic and cultural power within the nation’s boundaries” (p. 612). Nowadays, the advancement of digital technology blurs the differentiation of subtitling and dubbing countries (Gambier, 2013). Viewers are empowered with more options to choose from for better enjoyment of imported media content (Chaume, 2013).

In the case of Hong Kong SAR, China, most of the imported films are subtitled. As an in-house translator for a multilingual subtitling and dubbing company based in Hong Kong from 2008 to 2011, I noticed that the demand for subtitling definitely outweighed that for dubbing. However, Chung (2005) suggests that there is a shift from subtitling to dubbing, beginning from 2000, based on her interview results with Hong Kong film industry insiders. In Chung’s report, one of her interviewees points out that animated films or Asian comedies aimed at audiences aged 15 or below were the only dubbed releases in the Hong Kong market before 2000. Chung highlights that the reason for the shift is partly because of the decline of English standards in the new millenium. Besides, according to Chung, one of the interviewees predicted that more films, maybe even the blockbusters, will be dubbed if the standard of English falls further. Nevertheless, Chung provides no quantitative data or in-depth analysis to support her claims. There is also a lack of AVT research focused on the discussion of the shift in distribution mode for film. Against this backdrop, I am motivated to validate the shift with the support of quantitative data and to examine the factors that have influenced the choice of the audience between subtitling and dubbing in Hong Kong SAR, China.

The aim of this study is to explore the preference of the audience towards subtitling and dubbing for imported films in Hong Kong SAR, China. Imported films refer to films shown in Hong Kong cinemas that are not produced by a Hong Kong registered company nor a production company that at least has a company registered in Hong Kong, or that do not have a 50% or more involvement in the film by Hong Kong locals or permanent residents of Hong Kong (Hong Kong Box Office Limited, n.d.). I limited the scope of this study to focus on merely one audiovisual medium—cinema—mainly because the shift that Chung (2005) claims to take place is within the film market of Hong Kong. The situation would become too complicated for facilitating effective analysis if other audiovisual media such as television and video are included. The research period is set to be between 1990 and 2017, so as to validate the shift of audience preference from subtitling to dubbing that is said to have taken place starting from 2000 and to portray the scenario in recent years. In addition, I also endeavour to examine the underlying factors that have influenced the preference of the audience towards the two translation modes. However, I do not intend to examine why the identified factors played a role in the shift. Hence, my objective is to answer the following two research questions: (1) Is there a shift in audience preference from subtitling to dubbing for imported films in Hong Kong over the period from 1990 to 2017? (2) What are the key characteristics of the shift?

2. The dichotomy between subtitling and dubbing

2.1 Endless dilemma: Subtitling or dubbing?

The question of whether subtitling or dubbing is preferred in the field of AVT has been discussed vigorously by translation scholars since the emergence of the two translation modes. Many scholars (e.g. Caillé, 1960; Cary, 1960; Danan, 1991; Kilborn, 1989, 1993; Reid, 1978; Vöge, 1977) have compared and contrasted the advantages and disadvantages of subtitling and dubbing from both technical and linguistic perspectives. However, as Koolstra et al. (2002) indicate, “an advantage connected with one method can, in fact, be regarded as a disadvantage of the other method and vice versa” (p. 345). Thus, it is difficult to reach a definitive conclusion as to whether to choose subtitling or dubbing as the translation mode for audiovisual materials and put an end to the persistent debate. To understand the overall discussion throughout the history of AVT, I have summed up the viewpoints for and against the two translation modes into five aspects accordingly.

2.1.1 Cost and efficiency

In this aspect, the cost is unquestionably one of the major factors that govern the choice of subtitling and dubbing, particularly from the perspective of producers. The cost of dubbing is much higher than that of subtitling because the process of dubbing is time-consuming and complex with more professionals involved, such as translators, adaptors or scriptwriters, dubbing directors and actors as well as sound technicians (Díaz-Cintas & Orero, 2010). Having said that, the cost would not be a matter of concern in the case that revenue captured or generated by the adoption of dubbing is significant enough (Tveit, 2009). Apart from the financial consideration, subtitling also shows “a greater economy of expression” (ibid., p. 88) because subtitles have to be concise and precise to accommodate as much information and meaning in as little space as possible (Mera, 1999). The downside of this feature certainly is the inevitable loss of information due to the spatially and temporally constraining nature of subtitling. On the contrary, as Koolstra et al. (2002) claim, subtitling can be more taxing for viewers since they are forced to split their attention between subtitles and images. It is often assumed that watching a subtitled audiovisual text takes more mental effort than that of a dubbed one (ibid.). In this regard, dubbing is considered to ease the effort of following the dynamic development of an audiovisual text due to the cinematic illusion created by dubbing (Díaz-Cintas, 1999). Therefore, it is a more effective method to translate audiovisual materials for children or viewers with lower levels of literacy (Pérez-González, 2009).

2.1.2 Ideology and censorship

Since dubbing involves the substitution of the original soundtrack with a translated one, it is easier to hide the foreign elements that appear in an audiovisual text by creating the illusion that the screen characters speak the target audience’s language (Danan, 1991). In this sense, foreign dialogues are forced to conform to the domestic norms and thus, dubbing can be regarded as “an assertion of the supremacy of the national language and its unchallenged political, economic and cultural power” (ibid., p. 612). In contrast, subtitling, which preserves the original soundtrack, constantly reminds of the foreignness of an audiovisual text and “indirectly promotes the use of a foreign language as an everyday function in addition to creating an interest to a foreign culture” (ibid, p. 613). Still, censorship may occur in subtitling, but it is relatively hard to achieve without being noticed by attentive viewers (Koolstra et al., 2002). Furthermore, swear words and taboo expressions tend to be toned down or deleted to produce normalised subtitles. This is because it is believed that the impact of swear words and taboo expressions in their written forms is more offensive than their spoken form (Díaz-Cintas, 2012). Gottlieb (2005) offers the criticism that the spatial and temporal constraints of subtitling may serve as an excuse for omitting controversial or troublesome elements of the original dialogue.

2.1.3 Authenticity, and aesthetic and artistic integrity

Both subtitling and dubbing unavoidably present some loss compared to the source text. With respect to dubbing, in addition to its manipulating nature, the practice of replacing the original voices also causes the loss of tone of voice, stress, and intonation of the original dialogue which may convey a great deal of information, leading to the loss of authenticity and credibility of the dubbed products (Tveit, 2009). Yet, one may argue that dubbing does not distract the viewers with additional text on screen, resulting in a more authentic viewing experience (Mera, 1999). It is also worth noting that the substitution of the original dialogue in dubbing allows the viewers to understand overlapped or background voices (Mera, 1999), which may probably be eliminated by subtitlers due to the spatial and temporal restrictions of subtitling. Besides, as Tveit (2009) indicates, dubbing can retain the informal stylistic features of the source voices better than subtitling, which involves the rendering of informal spoken texts to more formal written texts. In contrast, the artistic unity of image and sound in subtitling is lost when the source voices are rendered to on-screen texts (Koolstra et al., 2002). Despite this, subtitling, in fact, “respects the aesthetic and artistic integrity of the original text” (Pérez-González, 2009, p. 16).

2.1.4 Pedagogical value

In subtitling, the duality of voice and text presentation promotes foreign language acquisition. Viewers can listen to the pronunciation of the words in a foreign language and understand the meaning of the words through reading subtitles, which in turn enhances the reading skills of viewers (Koolstra et al., 2002). In dubbing, the possibility of listening to the viewers’ own languages can stimulate the development of linguistic skills through exposure to both known and unknown words, sentence structures, and expressions in the respective languages (ibid.).

2.1.5 Personal preference

Up until this point, it has been fairly obvious that both subtitling and dubbing have their own benefits and drawbacks, and thus it is perplexing to come up with a decision preferring either subtitling or dubbing based on the theoretical debate provoked by translation scholars. Among them, some propose that the preference of viewers should be taken into consideration. As Ivarsson and Carroll (1998) claim, “the question of which method should be preferred seems to have more to do with what an audience is used to than rational arguments” (p. 37). Koolstra et al., (2002) assent to this claim and suggest that the weighing of the advantages and disadvantages of subtitling and dubbing is “largely dependent on habituation” (p. 347). If audiences are used to one translation practice, its disadvantages seem not to matter anymore (ibid.).

2.2 Solving the dilemma: An audience-oriented perspective

Two decades ago, the translation studies community began to acknowledge the co-existence of subtitling and dubbing for the benefits of audiences (Chaume, 2012; Díaz-Cintas, 1999; Ivarsson & Carroll, 1998; Koolstra et al., 2002; Matamala, Perego, & Bottiroli, 2017; Mera, 1999). Díaz-Cintas (1999) argues that since the two translation practices have their own strengths and shortcomings, we should accept that both can have their own places in the world of AVT and that they could be combined perfectly to offer the public a wide spectrum of possibilities in an ideal society. Matamala et al. (2017) are in line with Díaz-Cintas’s suggestion and add that viewers should be empowered and offered as many options as possible to choose from, allowing them to select the content that is most suitable for their personal needs. Moreover, Mera (1999) and Koolstra et al., (2002) propose to choose a method for each audiovisual text on the basis of its type and target audience because both subtitling and dubbing have their own distinct qualities. Koolstra et al., (2002) in particular refuse to follow the tradition of the categorisation of countries or regions as ‘subtitling’ and ‘dubbing’ ones since the authors believe that this kind of categorisation is unnecessary in the era of globalisation and digitalisation (ibid.).

Although translation scholars have proposed to resolve the debate of subtitling and dubbing from the perspective of audience, only a limited number of audience reception studies have been conducted to compare and contrast the effect of the two translation practices on viewers (e.g. Bucaria, 2005; Fuentes Luque, 2003; Perego, Del Missier, & Bottiroli, 2015; Perego, Del Missier, & Straga, 2018; Matamala et al., 2017; Perego, Orrego-Carmona, & Bottiroli, 2016). To further validate the theoretical claims concerning the advantages and disadvantages of subtitling and dubbing, it is vital to generate more empirical evidence, so as to verify the arguments that have lasted for over five decades in the field of AVT in a more concrete and substantial way. This study thus seeks to contribute by analysing the quantitative data described in the next section to investigate the preference of the audience between subtitling and dubbing in Hong Kong.

3. Data description

3.1 Data collection

In order to address the research questions of this study, I started by building up a corpus with the data of imported films in Hong Kong SAR, China between 1990 and 2017. The data were extracted with two methods. The first method was to search through the film database created and managed by Hong Kong Box Office Limited (HKBO) (http://www.hkbo.com.hk/search-engine.html), which was established jointly by the Hong Kong Theatres Association Limited (HKTA) and the Hong Kong Motion Picture Industry Association Limited (MPIA) in order to keep abreast of time and the newest developments of the film industry of Hong Kong. The database is reliable and trustworthy because HKBO is an organisation responsible for providing detailed information on films as well as box office revenues and analysis to subscribed industry insiders only. I collected two sets of data from the database. The first set of data includes the following categories for each year between 1990 and 2017:

· The total number of films (first run)

· The number of Hong Kong films (first run)

· The number of imported films (first run)

· The number of imported films by country / region (first run)

The second set of data contains the dubbed imported films between 1990 and 2017 with the following information:

· Film name

· Genre

· Release year

· Film category1This is further explained in Section 4.1.2. For more details, please refer to the website of the Communications and Creative Industries Branch of the Commerce and Economic Development Bureau of Hong Kong (https://www.cedb.gov.hk/ccib/eng/film/film_1.htm).

· Source language

The database of HKBO does not contain any information about which film was subtitled or dubbed for public screening. Therefore, it was necessary to use another method to categorise which translation mode was used for individual imported films, enabling systematic and accurate elicitation of relevant data from the database for in-depth analysis. The second method I adopted is to search through Google with a combination of keywords including dubbing (配音), dubbed version (配音版), Yue Chinese (粵语)2Although we refer to the spoken Chinese used in Hong Kong as Cantonese (广东话), it is generally called Yue Chinese (粵语) which is being spoken in Guangdong, Guangxi and other surrounding areas of China. The Cantonese dubbed versions of any films are generally called the Yue Chinese version (粵语版) by Hong Kong cinemas., Yue Chinese version (粵语版), Hong Kong (香港), film review (影评) screening (上映), public screening (公映), film (电影), and cinema (戏院) together with respective film names and release years. In order to elevate the reliability of the data collected via Google, a cross-checking method was employed to validate the data by using multiple data sources available online. The data collected with the two methods described here were then combined and analysed diachronically with the method described in the next section.

3.2 Analysis method: Periodisation

In historical approach, periodisation is “the process of dividing the chronological narrative into separately labeled sequential time periods with fairly distinct beginning and ending points” (Hollander, Rassuli, Jones, & Dix, 2005, p. 32). It “involves reducing nature to its observable, repeating elements” (Matthews, 2013, p. 253). Scholars categorise periods of history to aid analysis of their data by identifying major trends or characteristics of a certain period of time (Periodization, 2011). “There is often a ‘crucial’ moment at the change of a period when the new trend […] conflicts with the old trend” (ibid., n.p.).

In this study, my objective is to validate the shift in audience preference from subtitling and dubbing in Hong Kong SAR, China and to identify the factors that influenced the shift. To achieve this, I collected the data described in the preceding section and analysed several attributes of each film, including release year, genre, film category and source language. The results clearly show that there is an uprising trend towards adoption of dubbing across the period between 1990 and 2017. The trend can be roughly divided into three different phases. Each phrase is examined in detail to identify the influencing factors in the next session.

4. Data analysis

4.1 Subtitling or dubbing? An overview of the trend

4.1.1 The big picture: Hong Kong film market

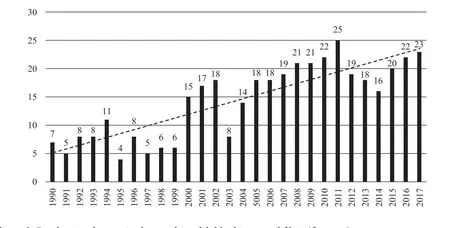

Before scrutinising the trend of dubbing for imported films in Hong Kong SAR, China over the period from 1990 to 2017, it is worth taking a brief look at the Hong Kong film market in the same period of time (see Figure 4.1). The Hong Kong film market has always been dominated by imported films, except for 1993 when the number of Hong Kong films almost reached that of imported films. It is also the year when the Hong Kong film industry reached its prime. The trend of Hong Kong films and imported films were poles apart between 1990 and 2000. In this period, when the number of imported films decreased, the number of Hong Kong films increased and vice versa. However, the number of Hong Kong films began to decline from 2001 and remained relatively flat between 2005 and 2017. The number of imported films started to drop a year earlier than that of Hong Kong films, but then showed a sign of slow growth between 2008 and 2017.

Figure 1. Diachronic changes in the total number of films and the number of Hong Kong films and imported films

4.1.2 The trend of dubbing adoption

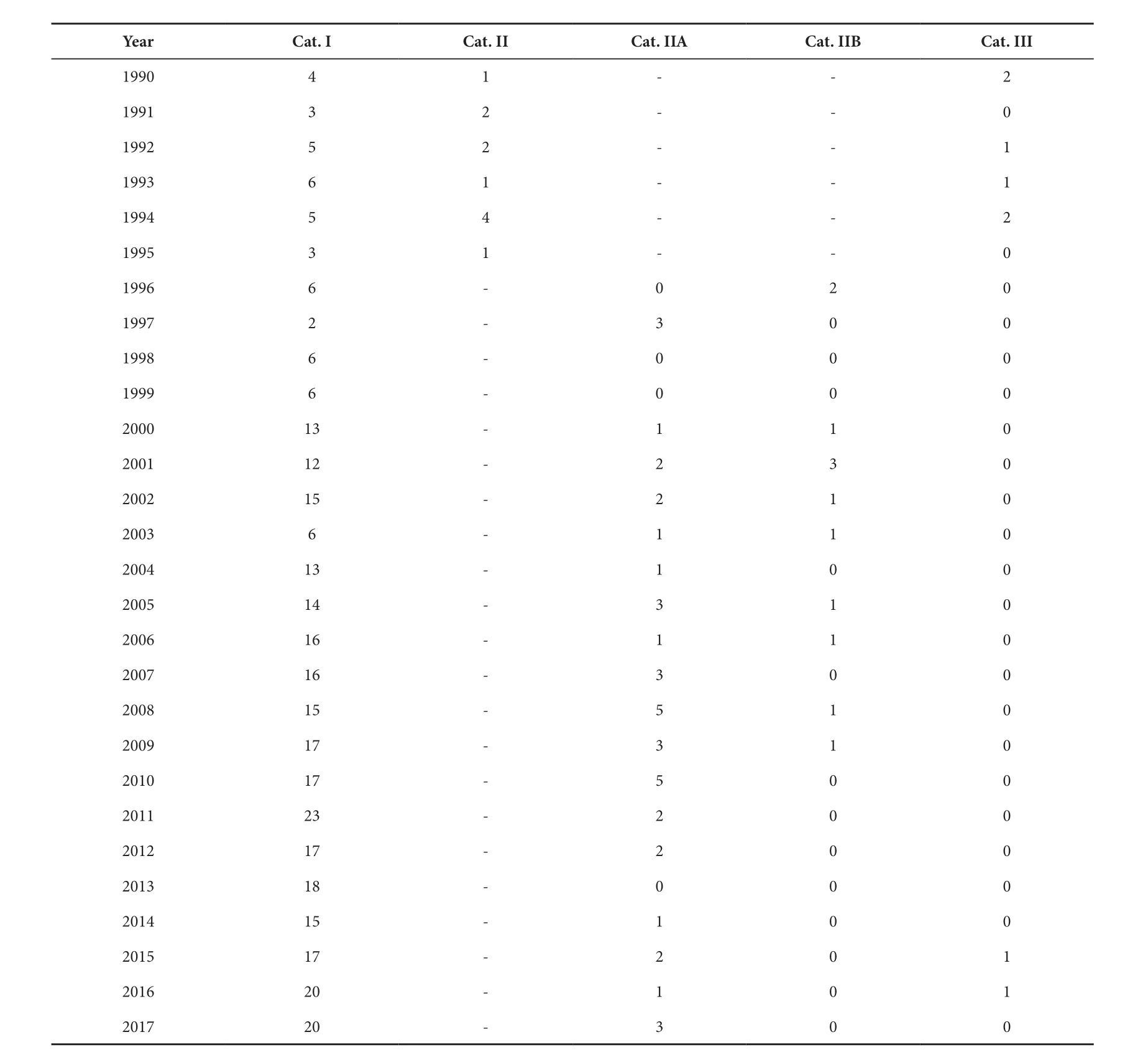

My research results support the fact that subtitling has been the major distribution mode for imported films in Hong Kong SAR, China. The number of dubbed imported films was insignificant compared to that of subtitled ones. Figure 4.2 indicates the number of dubbed imported films in Hong Kong over the period from 1990 to 2017. Overall, there was an uprising trend of adopting dubbing for imported films over the period of almost three decades. In the first decade, which is between 1990 and 1999, the number of dubbed films was merely in the single digits, excluding 1994 when the number of dubbed films reached eleven. The number of dubbed films began to climb up in the second decade, which is from 2000 to 2009. The year 2003 was an exception and this is further discussed in Section 4.2.2. In contrast to the uprising trend of dubbing adoption, the number of imported films, indeed, encountered a descending trend between 2000 and 2007 (see Figure 4.1). In the third decade, which is from 2010 to 2017, the number of dubbed films reached its peak in 2011 before declining for three consecutive years. From 2015, the number of dubbed films recovered and possibly demonstrated an uprising trend again.

Figure 2. Diachronic changes in the number of dubbed imported films (first run)

Preliminary analysis of the collected data reveals the uprising trend of dubbing adoption in Hong Kong. Figure 4 shows the number of dubbed imported films by film category over the period from 1990 to 2017. The current film category of Hong Kong has three levels of main ratings and two sub-ratings for one level. Category I is suitable for all ages; Category IIA is not suitable for children; Category IIB is not suitable for young people and children; and Category III is for people aged 18 or above only. Before 1995, there were only three levels of main ratings: I, II and III. In the period between 1990 and 1999 when the number of dubbed films was low, a total of six films in Category III and two films in Category IIB were dubbed. All of them were animation. This finding somehow contradicts Chung’s (2005) report that animated films aimed at audiences aged 15 or below were the only dubbed releases in Hong Kong before 2000. In the period between 2000 and 2009, dubbed release in Category III disappeared while the number of dubbed films in Category IIB reached ten over the said period of time. However, in the period between 2010 and 2017, the number of dubbed films in Category IIB dropped to zero whereas dubbed releases in Category III reappeared in 2015 and 2016 respectively. Hence, it is possible to conclude that the uprising trend of dubbing adoption in Hong Kong can be roughly divided into three different phases: (1) 1990—1999, (2) 2000—2009 and (3) 2010—2017.

Figure 3. The number of dubbed imported films (first run) by film category between 1990 and 2017

The aforementioned categorisation is further supported by analysing the collected data from another perspective—the number of dubbed imported films by source language. In the first phase, the source languages of dubbed films were mainly English (29 films) and Japanese (40 films), except one in Persian. In the second phase, the source languages of dubbed films became more diverse. Apart from English (102 films) and Japanese (45 films), there were French (5 films), Italian (1 film), South Korean (7 films), Mandarin Chinese (5 films) and Thai films (4 films). All of the dubbed Thai and South Korean films were non-animated and fell into the genre of comedy. For other source languages that emerged in this phase, only one non-animated French film was a comedy. The film is calledYamakasi(20011The year of film mentioned in this study is the release year of film in Hong Kong.) which features a group of parkour practitioners. As discussed above, there were ten dubbed films which fell into Category IIB in this phase. In fact, seven out of ten films were non-animated comedies. In the third phase, however, the diversity of source language reduced. Asian comedies that emerged in the second phase completely vanished. The source languages that appeared in this phase were English (112 films), Japanese (39 films), French (4 films), Mandarin Chinese (9 films), and Spanish (2 films). As discussed above, two films in Category III were dubbed in this phase and their source languages were both English. One is an animated comedy calledSausage Party(2016) and the other one is calledWhat We Do in the Shadows(2015), a New Zealand mockumentary horror comedy co-directed by Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement.

4.2 A shift in audience preference? An analysis of the influencing factors

The findings of the preliminary analysis prove that there is a shift from subtitling to dubbing in Hong Kong between the period 1990 and 2017. One may wonder how the shift in distribution mode is related to the shift in audience preference. According to Fong (2009), the decisions and strategies for film distribution in Hong Kong, including the selection of film, translation, and promotion are driven by market trends and the audience’s needs. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that the shift from subtitling to dubbing reflects the shift in audience preference towards dubbing. Consequently, I analyse the three respective phases of the shift by incorporating the major events or incidents that occurred in Hong Kong over the same period of time to examine the factors that affected the preference of Hong Kong audiences between subtitling and dubbing.

4.2.1 Phase 1: 1990–1999

There are several events or incidents that might have exerted influence on audience preference between subtitling and dubbing in this phase. One of the major events comprises the political and ideological changes that have taken place since 1997. Hong Kong had been under British rule from 1841 to 1997. Hence, it had been exposed to Western culture for a prolonged period of time. While under British rule, Chinese2Both the British Hong Kong government and the Hong Kong SAR government did not specify the type of Chinese to be used as the official language of Hong Kong. Hence, Chinese was generally referred to as spoken Cantonese and written Mandarin Chinese prior to the handover; after the handover, Chinese is referred to as spoken Cantonese, spoken Mandarin Chinese and written Mandarin Chinese under the “biliterate and trilingual” policy.was appointed as an official language only in 1974. According to Poon (2004), prior to the handover, Hong Kong was a diglossic society in which the bilingual situation was imposed. English enjoyed a supremely high status, regardless of the official language status that Chinese gained in the 1970s (ibid.). Since the handover, the language policy has changed as the government attempts to promote the status of Chinese and the use of Cantonese and Mandarin Chinese in Hong Kong (ibid.). The change in the political situation and language policy after the handover might have laid the foundation for the increase in dubbing adoption in Phases 2 and 3.

Additionally, the incorporation of Cantonese phrases into Mandarin Chinese subtitles that started in the late 1980s also exerted influence on audience preference between subtitling and dubbing. In Hong Kong, people speak in Cantonese but write in Mandarin Chinese. Hence, Cantonese is used for dubbing while Mandarin Chinese is used for subtitling. This practice has not been affected by the handover of Hong Kong. Cantonese is regarded as a lively and energetic language that is tolerant of foreign influences, compared to Mandarin Chinese which is the national language with fewer identifiable regional features (Fong, 2009). Cantonese is also characterised by “the variety and colour of its repertoire of vulgarisms and swear words” (ibid., 45). According to a survey on the attitude of Hong Kong audience towards incorporating Cantonese into subtitles conducted by Lo (2001), nearly 60 percent of the 413 respondents agree or strongly agree that Cantonese subtitles are applicable to English comedies or popular films and that Cantonese is better than Mandarin Chinese in translating the spirit of comedies or funny scenes (p. 127). About 58 per cent consider that Cantonese is better than Mandarin Chinese in rendering the spirit of the original English vulgar expressions (Lo, 2001, p. 127). Along these lines, using Cantonese in subtitles is a justifiable act to translate culture references, such as humour, to recreate an effect on the target audiences as close as that on the source audiences created by the source dialogues. This might lower or even eliminate the need for dubbing English-speaking films that did not target children or young people, since subtitling is capable of delivering the original spirit of the source dialogues and enhancing the enjoyment of film viewing with the use of lively Cantonese phrases.

Furthermore, the import of Japanese animation to the cinemas of Hong Kong in the late 1980s might have contributed to the change in audiences’ choice between subtitling and dubbing in this phase. William Kong, a famous Hong Kong film producer and the president of Edko Films Limited, is said to be the person who paved the way for the import of Japanese animation in Hong Kong (Chenzj, 2018). He captured a huge success with the screening of Studio Ghibli’s work,Castle in the Sky(1987), which was initially screened with Chinese subtitles and the dubbed version was screened later when the box office soared (ibid.). This success opened up a glorious decade for Japanese animated films. In this decade, a variety of works, including those targeting adults such as the seriesCrying FreemanandWicked City, screened in cinemas in Hong Kong SAR, China. The Japanese animated films imported in the early 1990s were all released in dubbed versions. However, the relatively low box office return ofWicked City 3(1993) compared to the previous two serial films marked the fall of Japanese animated films for adults in Hong Kong SAR, China (Lin, 2012). In 1996, the golden age of Japanese animation in the Hong Kong film market came to an end whenYuyu Hakusho – Invaders from Hell(1996) recorded a box office return less than 200,000 Hong Kong dollars (ibid.). Thus, it is clear that Hong Kong audiences were able to show their preferences via the box office and influence the choices and strategies of the film distributors accordingly.

4.2.2 Phase 2: 2000–2009

In this phase, the features of audience preference towards subtitling and dubbing are completely different from Phase 1. As discussed in Section 4.1, dubbed releases for Asian comedies, particularly Thai and Korean, emerged in this decade. This feature, indeed, was triggered by the introduction of the first Thai film called The Iron Ladies (2000). The film was dubbed because the distributor was concerned about the unfamiliarity of Thai culture to Hong Kong audiences (Hui, 2017). The dubbing script was not simply a translation, but a rewriting that was largely localised to engage Hong Kong audiences and the comical effect was further enhanced with the appointment of professional actors, popular singers, comedians, and celebrities as dubbing actors (Hui, 2017; Movie Forest, 2016). This was not a newly adopted practice as the dubbed version ofNausicaä of the Valley of the Wind(1989) was also heavily adapted1According to Chenzj (2018), the theme of the original version is about environmental protection and anti-war, but the theme of the dubbed version released in Hong Kong is about democracy, revolution, and anti-war.and dubbed by famous singers and comedians (Chenzj, 2018). In 2001, the French comedyYamakasi(2001) followed this formula for success and took a further step to rewrite the dubbing script to create rhythmic lines. The dubbing actors of this film were from a Cantonese hip-hop and rap group called LMF. This formulaic success proved to have captured the interest of Hong Kong audiences and boosted the box office revenues, providing economic incentives for the film distributors to choose dubbing over subtitling.

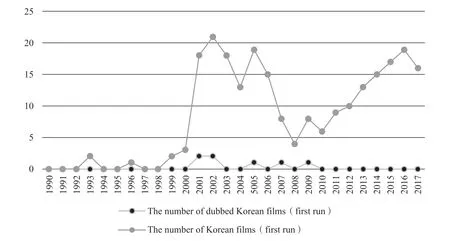

In addition, the Korean wave that arose in the late 1990s and swept across Hong Kong SAR, China in this phase significantly impacted the preference of audiences between subtitling and dubbing. According to Shim (2006), a Korean blockbuster,Shiri(1999), achieved critical and financial success, leading to the rise of Korean films in cinemas across Asia. On top of this, Korean pop music and drama also grew in popularity at the same time (ibid.). The Hong Kong film market naturally sought to capitalise on the upsurge of interest in the Korean wave. Figure 4.3 shows the number of Korean films and dubbed Korean films over the period between 1990 and 2017. The figure corroborates the rise of Korean films that occurred in the 2000s. The number of Korean films suddenly increased from three in 2000 to eighteen in 2001 and reached its peak in 2002. The dubbed Korean films began to be released in the Hong Kong market in 2001. All of the dubbed Korean films in this phrase were comedies. It is obvious that the reception of dubbed comedies by Hong Kong audiences played a crucial role in determining the distribution mode for Korean films.

The findings in Section 4.1 point out that there was a special incident that suppressed the adoption of dubbing in 2003. This was the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong. During the peak of the outbreak, schools were suspended, businesses were closed, and social activities were largely reduced. People avoided visiting confined spaces, such as shopping centres and cinemas, since the medium of transmission was unclear at that time. This caused extremely low box office receipts in the time of SARS outbreak, leading to a significant reduction in the number of dubbed films to save costs.

Figure 4. Diachronic changes in the number of Korean films and dubbed Korean films (first run)

4.2.3 Phase 3: 2010–2017

In Phase 3, the main factor that influenced the trend towards dubbing adoption was the personal preference of Hong Kong audiences. One of the features of the shift in audience preference from subtitling and dubbing in this phase is the disappearance of dubbed Asian comedies. This might have been caused by the change in the personal preference of the audiences. As analysed above, Hong Kong audiences have a strong tendency towards subtitling as it has long been the main distribution mode in Hong Kong. Dubbing has been adopted for films targeting children or younger people and non-Western films when they were first introduced to the Hong Kong market. In the past decade, Hong Kong audiences were substantially exposed to Asian cultures and their audiovisual materials, thanks to the spread of fansubbing, a term that initially referred to the amateur subtitling of Japanese animation which arose in the mid-1990s (Díaz-Cintas & Muñoz Sánchez, 2006). Today, a great variety of audiovisual materials, including animation, drama, film, and TV show, have been fansubbed and circulated on the Internet. Together with the advent of ondemand services, such as Netflix, the practice of “binge-watching” (追剧), which means “to watch many or all episodes of a TV series in rapid succession” (Merriam-Webster), developed in this phase. This practice indeed reinforced the reception of subtitling among audiences. Ultimately, the audiences became used to watching foreign audiovisual materials with the screen character’s voices and subtitles, hindering the adoption of dubbing for translating non-Western films. Nevertheless, the formula for success in dubbing adoption that developed in Phase 2 remained as an effective strategy for the film distributors to draw the attention of the audiences since the two dubbed English comedies,Sausage Party(2016) andWhat We Do in the Shadows(2015), gained critical acclaim with their outstanding rewritten and localised scripts.

5. Conclusion

In this study, I have explored the preference of audiences towards subtitling and dubbing for imported cinema films in Hong Kong and examined the factors that affected the preference of the audience. To answer the research questions, I created a corpus with the data of imported films in Hong Kong between the period 1990 and 2017. Then, I analysed the data with the method of periodisation to validate the shift in audience preference from subtitling to dubbing and identify the influencing factors. Despite the fact that the data on distribution mode were scattered throughout the Internet and that Hong Kong does not have any official statistics or data that indicate the number of films released in their subtitled or dubbed version to facilitate more systemic and effective analysis, this study is still able to provide an insight into the situation of Hong Kong.

The analysis of the data suggests that there is a shift in audience preference from subtitling to dubbing in Hong Kong. The uprising trend of the shift can be categorised into three different phases. In Phase 1, the number of dubbed films is the lowest among the three phases. The influencing factors of this phase include the ideological transformation that resulted from the handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to China; the incorporation of Cantonese phrases into Mandarin Chinese subtitles for a more authentic taste of translation; and the import of Japanese animation to the Hong Kong cinemas to draw the interest of audiences. In Phase 2, the number of dubbed films climbed up and maintained an uprising trend towards Phase 3. The factors that influenced the preference of audiences are the import of the first Thai film and the upsurge of the Korean wave which fostered the formula for success in dubbing adoption; and the outbreak of SARS in 2003 that drove the box office returns down to new lows. In the last phase, the number of dubbed films fluctuates, but remains at a high level compared to the previous two phases. The factor that played a crucial role in determining the distribution mode is the audience preference which is affected by other elements such as fansubbing and the pursuit of the authenticity created by subtitling. Some of the influencing factors identified in the analysis fall into four of the five main aspects of the debate concluded in Section 2, namely cost, ideology, authenticity, and personal preference. Although the current debate on the choice between subtitling and dubbing is principally theoretical, it is somehow able to shed light on the real-world situations.

Apart from addressing the research questions, this study has also allowed me to discover some possibilities for improvement and further research. First of all, I would consider it necessary for HKBO to update its database to include the details of distribution mode for each imported film. HKBO may further differentiate the box office data into subtitled and dubbed version for the film distributors to examine the preference of audiences, so as to optimise the decisions and strategies of distribution and provide the most suitable option for the audiences. Additionally, I would suggest the government or other organisations related to the Hong Kong film industry conduct a large-scale survey to investigate the preference of Hong Kong audiences towards subtitling and dubbing, similar to those conducted in Europe. This will provide an opportunity for both the Hong Kong film industry and translation scholars to grasp the current situation in Hong Kong. Last but not least, it would be meaningful to carry out further research on audience reception to address the attitude of Hong Kong audiences towards subtitling and dubbing. Currently, there is an insignificant number of empirical studies concerning the reception of audiences in the field of AVT research. Any empirical research on audience reception may contribute to shaping this area of study and verify the theoretical debate discussed throughout the history of AVT.

Filmography

A Bug’s Life. 1998.

Castle in the Sky. 1987.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. 1989.

Sausage Party. 2016.

Shiri. 1999.

The Iron Ladies. 2000.

Toy Story. 1996.

Wicked City 3. 1993.

What We Do in the Shadows. 2015.

Yamakasi. 2001.

Yuyu Hakusho – Invaders from Hell. 1996.

杂志排行

翻译界的其它文章

- Constraints and Challenges in Subtitling Chinese Films Into English

- Identity Construction of AVT Professionals in the Age of Non-Professionalism: A Self-Reflective Case Study of CCTV-4 Program Subtitling

- The Subtitling of Swearing in Criminal (2016) From English Into Chinese: A Multimodal Perspective

- Omission of Subject “I” in Subtitling: A Corpus Review of Audiovisual Works

- The Development and Practice of Audio Description in Hong Kong SAR, China

- A Sociological Investigation of Digitally Born Non-Professional Subtitling in China