A Sociological Investigation of Digitally Born Non-Professional Subtitling in China

2019-05-12SijingLU

Sijing LU

University of Liverpool

Abstract The advance of media and technology has enabled a growing number of Internet users without formal training to engage in the production of translation. Thriving with the advent of virtual community and advancement in computer technology, fansubbing has become a significant component among various forms of non-professional translation and has played the role of cultural broker in rendering and introducing foreign audiovisual products into other cultures. Against this backdrop, this article attempts to provide a sociological analysis of the fansubbing community ShinY in China. To achieve this purpose, the article employs Bourdieu’s analytical concept field (1985, 2010) and Levina and Arriaga’s (2014) digital sociology to uncover the offline and online social fields shaping the production of fansubbing, the conversion of capital proceeding constantly between offline and online fields, and the internal and external constraints of the subtitling production in ShinY. The results show that fansubbing is situated simultaneously as a sub-field of the offline subtitling field defined by subtitling capital, and the online field is secured by its attention capital. External sources of capital can be converted into online fields. In turn, capital accumulated in online fields can be imported into offline capital. The constant capital conversions ongoing between offline and online fields contribute to the different roles and positions of fansubbers. Additionally, through taking ShinY as an example, online non-professional subtitling displays principles of internal autonomy in terms of its mechanism of governance.

Keywords: online field, non-professional subtitling, sociological approach

1. Introduction

As a highly dynamic and inclusive interdiscipline, Translation Studies has experienced several shifts or turns over the past decades, moving from the “linguistic turn” in the 1970s to the “cultural turn” in 1980s and the “sociological turn” in the late 1990s (Wolf & Fukari, 2007). With the emergence and advancement of the Internet in the early 21st century, along with the increasing speed of globalisation and cultural communication, the need for scholars of translation studies to carefully evaluate the translation phenomena enabled by new media and technologies is necessary (Cronin, 2013). Studies in translation triggered by new media and the Internet emerged in the late 20th century and the major trend during this period is towards the assessment of the history and the operability of particular translation technologies in machine translation or translation memory tools (Littau, 2016). In the beginning of the 21st century, attention specifically focused on online non-professional translation has increased and various aspects have been illuminated (e.g. activist translation, collaborative translation, user-generated translation, community translation). Littau (2011) thus proposes that there is going to be a “media turn” within Translation Studies in the context of a diverse, mass-mediated society. The shift between oral, scribal, print and screen culture is considered to be the result of diverse technological innovations, and each alteration can influence the ways the spoken or written word came to be received (ibid.). Therefore, if technological innovations can have an impact on reading and writing, surely comparable results are also observable within the translation world.

In a digital era, one can publish their work in the public domain from any computer connected to a network. As a result, the traditional reader-author relationship has been broken. The reader becomes a writer by adding their own words or images to an existing site (McMurran, 2010). This participatory culture has also been noticed by media and cultural scholars when examining the trend of nonprofessional users becoming more involved and active in both the consumption and production process of media products. Seen through this light, the concept “user-generated content”, also known as “user-created content”, has been proposed in response to this participatory culture. Flew and Cunningham (2010, p. 53) describe user-generated content as “the way in which users as both re-mediators and direct producers of new media content engage in new forms of large-scale participation in the digital media spaces”. Drawing on this definition, scholars in translation studies such as Perrino (2009) and O’Hagan (2009) propose the term “user-generated translation” to refer to the phenomenon that Internet users, usually non-professional translators, voluntarily play the role of re-mediators and direct producers in rendering media content to a larger scale of users who somehow do not have access to the original source text. These non-professional translators operate on the basis of their knowledge of a given language as well as within genres that stimulate their interests. O’Hagan (2009) highlights that the term “user-generated translation” underlines the core position of social networking—a buzzword that emerged in the early 21st century as a result of new communication technologies. She further states that “implicit in social networking platforms is their recognition of the inherent human nature to socialize and interact, which will also facilitate tasks to be performed in different professional areas, including translation” (ibid.).

Going against this trend is fansubbing—a particular form of online non-professional translation, which could be described as an online subtitling activity made by fans for fans. Fansubbing has thrived with the advancement of information technology, becoming a global phenomenon. It contributes to rendering and introducing audiovisual materials from one culture into another. In China where strict censorship is conducted on the Internet, this particular form of non-professional translation plays a unique role in providing the latest foreign media programmes to the general public, especially to the young generation who shows a strong interest in foreign cultures. The collaborative nature of fansubbing along with their semi-professional work flow has led to O’Hagan’s (2008, p. 179) claim that “Translation Studies can no longer afford to overlook the fan translation phenomenon”. Fansubbing represents a field in which established subtitling norms and practices have been challenged by a high degree of productive freedom and empowerment of translators through the use of the Internet and collaborative intelligence. Previous literature has principally focused on the subtitling conventions and strategies in this non-professional practice, along with the discussion of their similarities to and differences from the professional industry (e.g. Caffrey, 2009; Díaz-Cintas & Muñoz Sánchez, 2006; Lee, 2014; Massidda, 2012; Pérez-González, 2007). Scholarly exploration has also extended from the above textual-centred studies to a more contextual analysis, including the work flow and mechanics in non-professional subtitling (e.g. Díaz-Cintas & Muñoz Sánchez, 2006; Pérez-González, 2007), the collective identities of non-professional subtitlers (e.g. Li, 2015), and the virtual network they construct (e.g. Liu & De Seta, 2015; Rong, 2014). However, the exploration in texts and community networks of non-professional subtitling has overlooked the external social structures and position of the fansubbing phenomenon. A sociological analysis can contribute to the study of nonprofessional translators as social beings who are situated and function in an environment of multiple social roles and dimensions. The shift of focus from the texts or communities to the external social context can best echo the “media turn” (Littau, 2011) which emphasises the relationship between translation and society. Seen through this light, this article initially discusses the proliferation of non-professional translation in a digital era, and then illustrates the relevance and compatibility of Bourdieu’s concept, thefield(1985, 2010), and Levina and Arriaga’s (2014) digital sociology in studying the position and structures of an online non-professional subtitling phenomenon. The article then offers insight into one of the largest Chinese fansub communities,ShinY, through participant observation, and attempts to map out (1) both the offline and online fields in whichShinYoperates, (2) the conversion of capital proceeding constantly between offline and online fields, (3) and the internal and external constraints shaping the subtitling production inShinY.

2. The proliferation of non-professional translation in the digital world

The advancement of media and technology has enabled a growing number of Internet users to produce translations themselves. The majority of them have not been professionally engaged in formal translation training, and they work as volunteers. Pérez-González and Susam-Saraeva (2012) define non-professional translators as “individuals not only without formal training in linguistic mediation but also working for free” (p. 151). Non-professional translators rely heavily on media and the Internet (O’Hagan, 2008). In fact, the history of non-professional translation is as old as the history of translation itself; as Martínez-Gómez (2015) points out, “the participation of untrained unremunerated individuals in all kinds of interlingual communication events throughout centuries is undeniable” (p. 205). Non-professional translation has existed for centuries. However, it is the recent advent of technology and the popularity of the Internet that have caused non-professional translations to mushroom and have foregrounded this particular field.Facebookwas a pioneer which began to encourage users to translate their website into different languages in 2007. However, it was not until September 2008 that the participatory translators ofFacebookhad reached a considerable size. Over 30,000 users worldwide participated in the translation of the website from English into 16 languages. The use of non-professional translators inFacebookis not primarily conceived as a way of cost saving. Instead, the leveraging of inherent enthusiasm for the website from its users was aimed at making the social media platform more accessible worldwide, a strategy which served well to encourage further user participation and popularity (Mesipuu, 2012).

With the increasing number of non-professional translators participating in a wider range of contexts, there are complex reasons for the proliferation of this phenomenon in the digital age. From a global transaction perspective, the development of non-professional translation practice can be seen as a result of the interplay between five dimensions: ethnoscapes (pertaining to the shifting distribution and mobility of people), finanscapes (the distribution of capital and commodities across individual countries), ideoscapes (the sets of political values and narratives to which each community subscribes), technoscapes (the level of technological development), and mediascapes (the distribution of the electronic capabilities to produce and disseminate media content) (Appadurai, 1990). The interface between ethnoscapes, finanscapes, and ideoscapes has resulted in a shortage of economic resources that “certain ethnic or political collectivities require to be represented in local and global forums, either through the publication of translated texts or their interpreter-mediated participation in high-profile meetings” (ibid.). This shortage may trigger social problems such as exclusion and alienation. The shortage and the shared desire for social integration have thus driven some activists to take part in translation activities. Additionally, the interface between technoscapes and mediascapes constitutes a productive context for the emergence of non-professional translation in the digital era. The advancement of technologies has given citizens more control over their media experience and this civic engagement in media has obscured the lines between “economics and culture, production and consumption, making and using media, and active or passive spectatorship of mediated culture” (Deuze, 2009, p. 148). In this respect, the process of convergence has indeed brought some new forms into the field of translation.

As seen from the above, non-professional translation has played a significant role in facilitating economic, cultural, social and commercial exchanges and challenging our traditional understandings of the translation profession. One of the latest popular activities triggered by this trend is that nonprofessional translators use translation as a tool to participate in the political discussion to challenge the dominant discourse. The Internet has become a “symbolic space” in which “peace activists” and “marginalized groups” who intend to challenge dominant discourses can “elaborate and practice a moral order in tune with their own narratives of the world” (Baker, 2006, p. 481). Translation provides these activists and groups with a chance to break national and linguistic boundaries. Simultaneously, the activist translators involved in this translation process are “beginning to organize themselves in various ways in order to elaborate their own narratives and play a distinct role in shaping an alternative vision of the world” (ibid.). In addition, the political participation initiated by non-professional translators also requires attention to be paid to the practice of subtitling. In 2000, an activist online community subtitled an interview of José María Aznar López, the former Prime Minister of Spain, and distributed the video online. This televised interview was originally broadcast by BBC News “against the background of the ongoing military conflict between Lebanon and Israel” (Pérez-González, 2010, p. 259). These politically engaged individuals are mostly non-professional translators who are not equipped with formal translation training. Through “interventionist forms of mediation”, they get themselves more involved in a wider process of “cultural resistance against global capitalist structures and institutions” (ibid.). Moreover, in contrast to the traditional activist communities that mainly focus on translation, the activist subtitlers actively participate in the appropriation and distribution of the mediation process (ibid.). Those active subtitlers in the community are often involved in “complex negotiations of narrative affinity among their members”, and this further emphasises that the notion of collective intelligence is particularly important in these sorts of “ad-hocracies” of activist translation.

With a specific scope in China, the proliferation of non-professional translation in the digital age mainly occurs in the activity of producing subtitles. This proliferation is mainly due to the deficiency and monotonousness of domestically produced films and TV dramas. Moreover, the censorship laws that are ostensibly to safeguard public morals and protect juveniles have removed, toned down, or rewritten nondomestic films and TV programs (Wang & Zhang, 2016). Audiences, especially the young generations, are thus stimulated to search for the original audiovisual products on the Internet. Within this social context, non-professional subtitling, or so-called fansubbing, has expanded and proliferated rapidly. Comparing non-professional subtitles with mainstream translation, fansubbing has absorbed the advantages of the industry, yet its translation style is usually not restricted by the orthodox translation standards that professional translators obey. Some of their translation goes beyond professional subtitling, including their promotion of neologisms, bilingual subtitles and colloquial register (ibid.). It can be inferred that fansubbers are using a “hybrid proposal” as coined by Massidda (2012) and draw on a well-balanced blend of the best resources used by both professionals and amateurs. The work flow of fansubbing shares several similarities to a typical professional subtitling production, while peer production shows a clear organisational division. Such decentralized organisation reveals a high level of efficiency in two dimensions. First, the distinction between digital production and consumption is blurred, thus enabling “an unprecedented scale of participation in the production of culture” (Rong, 2010, p. 4). Second, responsibilities and materials are allocated through a decentralised system rather than a hierarchical governance structure, with such a mechanism displaying a high level of adaptability to fast-paced and complex informational environments.

The self-mediation and high-efficiency nature of fansubbing has generated many new social and economic implications. For example, it has carved out a new non-profit market for digital consumption which targets Chinese online audiences. The Internet has enabled Chinese fansub groups to proliferate a “new style of neoliberal work ethic” by “integrating self-interest with the public interest and altruism with competition” (Hu, 2014, p. 440). Fansubbers are not only reliable and efficient sources of human capital who “become the subject of production” (ibid.), but also possess useful digital capital in the form of good-quality computers and Internet facilities. The neoliberal values of self-mediation have been incorporated into the fansubbing production process. The non-profit and volunteer devotion of Chinese fansubbing groups “contradict the capitalist logic of profit maximization”, and such peer production and free sharing become “immanent practices” through “agonistic giving”, “reciprocity-seeking”, “altruism”, and “companionship” (ibid.). Therefore, the neoliberal work ethics in fansub groups no longer privilege the formal labor economy, but have been defined with new meanings. For instance, Chinese fansubbing can be defined as a type of “moral economy” as coined by Scott (1976). The moral economy of fansubbing conforms to Hyde’s (2006) initial prescription of three dimensions in the “gift economy”, namely, to give, to accept, and to reciprocate. Chinese fansubbing groups are usually built on a non-monetary and nonprofit basis and provide free unlimited digital resources to fans without expecting rewards, yet they still can be seen to gain reputation or popularity after sending their “gifts”. It is worth noting that the gift economy of fansubbing does not mean it operates in a totally independent mode outside state distribution. Instead, it only generates another mode of exchange and circulation within the state territory.

It can be inferred that the non-professional translation activities triggered by the digital era have generated many new social and economic modes, such as the “new patterns” of production and distribution in Chinese fansubbing. Although these new patterns have embodied some autonomous elements, such as the aforementioned model of the gift economy, they are still heteronomous with the dominant state distribution. By referring to Bourdieu’s key concept offield(1985, 2010) and Levina and Arriaga’s (2014) development in digital sociology, the section below provides an analytical approach to studying and mapping out the complex social fields shaping an online non-professional subtitling phenomenon, and the conversion of capital between offline and online fields.

3. Bourdieu’s Field, digital sociology and online non-professional subtitling

Bourdieu’s (1985) concept of thefieldis usually seen as the fundamental element of his sociological theory. A field is defined as a social space with its own generated structures, operational laws, and logic; it is “a structure of objective relationships permitting the accounting for the concrete form of interactions” (p. 17). Although the notion offieldhad been proposed by other scholars long before Bourdieu, one key feature of Bourdieu’sfieldis its inclusion of the concept of “struggle”. According to Bourdieu (1985), in a social space, there are constant struggles for certain social positions and power relations among agents and institutions. Social agents are struggling for a more dominant position through accumulating certain stakes, or in Bourdieu’s words, through gaining various forms of capital. The possession of capital is relevant to the purpose of the given field and enables social agents to acquire, maintain and change a position in the field. Capital is thus defined into four dimensions based on their properties:

Economic capital, which is immediately and directly convertible into money and may be institutionalized in the forms of property rights; ... cultural capital, which is convertible, on certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalized in the forms of educational qualifications; ... social capital, made up of social obligations (“connections”), which is convertible, in certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalised in the form of a title of nobility. ... The symbolic capital is apprehended ... in a relationship of knowledge, or, more precisely, of misrecognition and recognition(Bourdieu, 2010, pp. 47-56).

The structure of a field is based on the distribution of various forms of capital and each field is dedicated to a social activity of acquiring a specific type of capital. For example, a scientific field is marked by a group of specialised agents that are able to judge scientific works and thereby accumulate scientific capital; a literary field is governed by literary agents who derive their activities through producing literary works (literary capital). Each field has its own rules of functioning, and a field is “a relatively autonomous domain of activity that responds to rules of functioning” (Hilgers & Mangez, 2015, p. 5). Based on Bourdieu’s illustration, the autonomisation of a social activity indicates the emergence and accumulation of a field-specific capital. In order to become more autonomous, the field makes its borderline clearer by increasing the “closure effect” (ibid.). Yet all fields, even if they are autonomous, are submerged into the most dominant field—the field of power. Thus, each field is regarded as being influenced by two opposing principles: an internal autonomous principle that defines the specific structures and values to the field, and an external heteronomous structure that applies to the hierarchy prevailing in the field of power (Mounier, 2001).

Among the more well-known explorations of Bourdieu’s concept of thefieldapplied to the field of translation is that of Hanna’s (2016) in the field of drama translation in Egypt. With a focus on the Arabic translation of Shakespeare’s tragedies, a detailed analysis of Bourdieu’s theory of the “field of cultural production” is provided, with the purpose of offering a new perspective on the genesis and development of drama translation in Egypt. He assumes that “translation is a socially situated phenomenon that is only fully appreciated in its socio-cultural milieu” (ibid.). He also proposes that a sociological analysis of translation using Bourdieu’s approach should take the social-cultural contexts and conditions into consideration. In addition, Bourdieu’s concepts of autonomy and heteronomy are significant in discussing the production process of cultural products in a particular field. As a matter of fact, there is no totally autonomous activity; the struggle to position drama translation as autonomous and heteronomous continues to this day. Hanna’s exploration echoes Bourdieu’s view that it is important to pursue a relational understanding of translation that emphasises the interplay of different fields rather than regarding them as isolated social spaces with defined boundaries. Meanwhile, Bourdieu’sfieldmakes it possible to investigate the production of a translation phenomenon with its complex network of relations that involves various agents and institutions.

Whilefieldis a powerful analytical tool to analyse social hierarchy and power distribution, it was originally designed to explore the social dynamics in offline worlds and less light has been shed on the investigation of translation practices involving elements of technological objects, such as in the case of digitally born non-professional subtitling. Scholars such as Di Stefano (2016) and Herzig (2016) admit the challenge in the lack of clarity of traditional Bourdieusian notions in the treatment of non-human factors, and advocate approaches which combine the interactions of social actions and digital aspects to the investigation of online practices. In the digital world filled with computer-mediated communications, there is the necessity to reconsider and complement the traditional Bourdieusianfieldwith a modern perspective, taking the relationship between human and technological factors into consideration. Following Bourdieu’s concept offield, Levina and Arriaga (2014) develop and propose a concept ofonline fieldto study the social dynamics of the online practices. Theonline fieldis defined as “a social space engaging agents in producing, evaluating, and consuming content online that is held together by shared interest and a set of power relations among agents sharing this interest” (p. 477). Similar to any offline social field, the online field can be repeatedly nested and overlapped. Just as in offline fields which are defined by field-specific capital, theonline fieldis characterised byattention capitalderived from the term “attention economy”.Attention capitalis a kind of recognition within theonline field, or as Franck (1999) initially coins it, “the social crediting of somebody’s earned attention”. It can be inferred that as attention capital indicates a symbol of power and status, it is a sub-type of what Bourdieu names as symbolic capital. The possession of different volumes and types of capital determines the distinct positions and diverse roles in online fields.

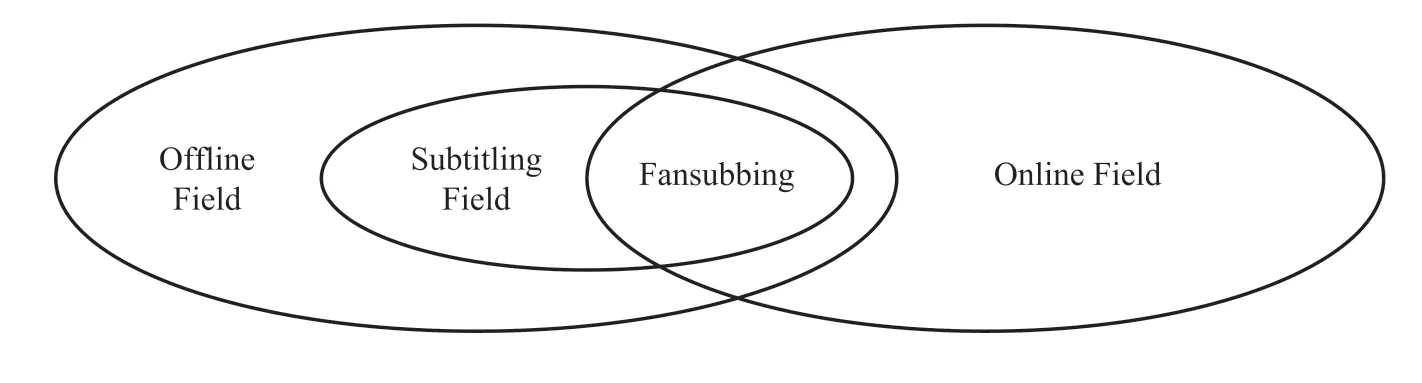

Besides the internal dynamics within the online field, another key point Levina and Arriaga (2014) developed is the interactions between online and offline fields. Although the existence of a field is defined by the production of a unique distinction when compared with other fields, external sources of capital can make a great impact on the social dynamics inside the field. This is also the case in anonline field. Levina and Arriaga argue that producers of an online platform use their external cultural capital to construct valuable information by bringing in their computer, artistic, or photographic skills, or they may also use their offline economic capital to pay for a server or advertisements. (ibid.) Their offline cultural and economic capital is thus converted into online cultural capital which enables them to conduct various online activities. On the contrary, capital from online fields can also be exported into other online and offline fields. For instance, an Instagram star can use his/her online popularity and reputation (online symbolic capital) to earn money (offline economic capital) in the offline society. The figure below is a summary of traditional Bourdieusian properties of thefieldand its development by Levina and Arriaga (2014) as applied in the case of non-professional subtitling. To supply the absence of discussing the technological aspects triggered by the Internet, this article builds on the traditional Bourdieusian concept offieldas it has been reconsidered by Levina and Arriaga (2014).

Table 1. Attributes of Field and Online Field applied in online non-professional subtitling

4. Situating non-professional subtitling in offline and online fields

4.1 The role of fansubbing in the offline subtitling field

Before gaining insight into the field of online non-professional subtitling, it is necessary to have a comprehensive understanding of its broader field — the field of subtitling. Following a Bourdieusian perspective, each social field is marked by a specific social activity and defined by its field-specific capital. Regarding the subtitling field, the field focuses on a social activity of producing subtitles, and agents inside the field require, accumulate, and compete for subtitling capital. Based on Bourdieu’s (1985) four dimensions of each type of capital, it is argued that subtitling capital can be also divided into cultural and symbolic dimensions. In terms of the cultural dimension, it can refer to the objectified form of cultural capital, including the subtitling devices or even computers a subtitler uses in the production of subtitles. The institutionalised form of cultural capital takes the form of academic qualifications, e.g. certificates of cultural competence, references to one’s subtitling certifications, skills, or English qualifications required by subtitlers. Subtitlers need to deal with various specific skills involved in subtitling, such as dealing with technical constraints (time and space constraints), producing timecodes, and possessing technical abilities in using subtitling software.

It is worth noting that even in the non-professional environment of fansubbing, either objectified or institutionalised cultural capital are sometimes required by the community leaders. This can be affirmed from the entry requirements in the recruitment process ofShinY. They require participants to possess certain subtitling software such asAegisub, Subtitle Workshop, Photoshop, high-speed Internet, and English certificates such asIELTS, TOEFLorCET1CET, abbreviation for College English Test, is a national English test in China. The test aims to ensure college students can meet the required English level in college-level studies. Currently the test is divided into two sub-levels (in ascending order): CET Band 4 and Band 6.before applying for participation (see figure 1 and 2 below). In addition, subtitling capital can also be symbolic. The symbolic dimension of capital is regarded as the most important type of capital by Bourdieu, as it embodies the symbols of power and status. In the subtitling field, it can refer to the recognition and acceptance of the importance of subtitling in society and the reputation of creating good subtitles. For example, in the field of fansubbing, communities such asYYets, TFL, ShinY, andYDYare among the earliest and most influential subtitle groups in China. They are often regarded as “fansubbing giants” and attract hundreds of fans and members to join in. These giant communities have a reputation in the field for producing subtitles of the highest quality and for working on the most up-to-date films and dramas. Their production model and management mechanism have great power in influencing and shaping other small, nascent fansubbing communities.

Figure 1. Recruitment poster of ShinY on the community’s forum

Figure 2. Recruitment poster of ShinY on the community’s Weibo1Weibo is a Chinese microblogging platform launched by Sina company in 2009. It has become one of the most popular social media platforms in China. The official website can be found at: https://www.weibo.com

4.2 Fansubbing as a sub-field in the online field

After mapping out the offline field shaping non-professional subtitling, this section gives insight into the online field in which non-professional subtitling is located. Similar to any offline field, each subfield of the online field has its own logic and structure in terms of agents and actions. Liang Liang, the founder of the biggest Chinese fansub communityYYets, uses the term “subtitle sharing” to summarise a range of online non-professional activities triggered by fansubbers1The original interview with Liang Liang, the founder of YYets, can be found at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201101/07/WS5a29ec20a3101a51ddf8da4b.html. Subtitle sharing includes a series of online actions such as producing, posting, viewing, downloading or archiving subtitles. Thus, as a subfield of online activities, fansub communities generate a specialised online field of producing and sharing subtitles. As discussed earlier, each online field shows multiple nesting. Some of the agents in the fansub field distinguish themselves through subtitling English material, and some also find a large variety of other more focused subfields, e.g. a field centred on Spanish (Xiyuximi, TreeHouse Sub), Japanese (Kamigami, NiePan, QingYi), Korean (TSKS, Maka), or Russian (Ruclub). In addition to the focused language, some fansub communities distinguish themselves through subtitling a particular audiovisual genre (e.g.Ocoursefocuses on subtitling open university courses).

According to Levina and Arriaga (2014), similar to the offline subtitling field which is defined and secured by subtitling capital, each online field is also defined by a field-specific capital — attention capital. Attention capital is a unique stake in virtual society. It can bring monetary rewards to online agents, either in the form of virtual or real credits. In the field of fansubbing, attention capital refers to the virtual credits, prestige and reputation a fansubber possesses. TakeShinYas an example. Attention capital is fulfilled by a virtual credit and prestige system on the forum. According to the system’s rules, the higher credits a fansubber earns, the higher prestige he/she would receive. Credits are marked in Arabic numerals and prestige is displayed in a combination of emojis alongside the member’s avatar (see figure 3). This system enables fansubbers to spot outstanding peer members and is a recognised place of showing one’s reputation. In an online field, the system represents a good example to materialise fansubbers’ symbolic status and attention capital. Fansubbers are encouraged to compete with peer members and keep accumulating their attention capital as a symbolic form of distinction in relation to other members. Due to the invertible nature of capital, having a large amount of attention capital could help fansubbers acquire more cultural capital, as the fansubbers who have a higher degree of attention capital usually have more access to the digital resources of the community.

Figure 3. Screenshot of a ShinY member’s credits and prestige on the forum (The emoji of sun, moon and star indicates the member’s level of prestige and the number 502 indicates the member’s current credits.)

According to Levina and Arriaga (2014), based on the volume of contributions and evaluations, agents in an online field can be fundamentally divided into two key groups — producers and consumers — with the further specific categories including passive lurkers, mass raters, platform designers, minor contributors, expert evaluators, popular producers and so on. However, based on the design choices of a platform, each online field would have its own rules and logic of defining the diverse types of contributions. Platform design choices to some extent can influence and shape the social dynamics by “designing how attention currency is allocated within an online field” (ibid.). TakeShinYas an example. Figure 4 below shows how much each agent type matters in the production of distinction in the field of fansubbing. Generally, there are passive fans and active fansubbers (e.g. platform designers, expert subtitlers, ordinary subtitlers, newbie subtitlers). Passive fans can be regarded as a type of consumer who are loyal fans in the community but do not have access to the translation process. InShinY, the community has established an official fan QQ group (see figure 5) for these passive fans. As passive fans do not participate in the production of subtitles and do not have opportunities to bring reputation or prestige to the community, they are considered as producing less cultural and symbolic output, or less cultural capital and symbolic capital. By contrast, active fansubbers are producers, referring to the fansubbers who actively take part in the process of creating and distributing subtitles. It is worth noting that one of the key agents in active fansubbing is platform designers. In fansubbing communities, platform designers usually refer to the community founders and administrators. They are in charge of the entire community and have a high degree of agency to decide how the online platforms such as the website, QQ groups, or forums are displayed and used, and how subtitled works are promoted and distributed. Community founders and administrators are of the highest status in a fansubbing community and have a large capacity to mobilise community members. They thus possess the largest volume of power and symbolic capital. Expert subtitlers, or the so-called “大神1“大神”, literally translated as “big god” in English, is a new term originating from game gurus and refers to the experts, legends or masters in a specific area.” (big god), may have a higher degree of cultural capital than any other types of members. They refer to the subtitlers who have a large breadth of knowledge and are expert in dealing with various translation and technical problems. In addition, the fansubbing community gives agency to passive fans by offering them the chance to give feedback on subtitles, such as leaving comments onWeibo, post bar, or forums. Although passive fans contribute to the assembly of a fansub community, the notion that defines the existence of the online field and the dynamics of the interactions is that of the active producers. It is the producers, or the active fansubbers that take the primary place in defining the given field.

Figure 4. An example of the structure of an online non-professional community, ShinY

Figure 5. Screenshot of the official QQ fan group of ShinY

Following a Bourdieusian perspective, the online field does exist independently and is closely associated with the offline field (see Figure 6 below). The conversion of capital proceeds constantly between the offline and online fields, and capital from offline sources plays a significant role in shaping social dynamics inside an online fansubbing community. For instance, a fansubber’s offline cultural capital, including translation skills and knowledge acquired in offline social activities, and their offline computer equipment and products, helps them to complete a subtitling project smoothly. In the same vein, capital accumulated in the online field can also be imported into offline practices. For example, the cultural capital they acquire in the online fansubbing field could be imported into their offline cultural capital. This happens when fansubbers want to be professional translators or subtitlers; they use online fansubbing communities as an opportunity to train their translation and subtitling skills. The online capital they accumulate constructs a solid foundation for their future career in the offline industry. In addition, based on Levina and Arriaga’s (2014) illustration, capital accumulated in one online field can be imported into other online fields. For example, a fansubber could use his subtitling skills acquired in a fansubbing community to establish a YouTube vlog through subtitling foreign videos. In this sense, his cultural capital accumulated in the fansub community is imported into another online platform.

Figure 6. Fansubbing’s overlapping position within offline and online fields

5. Community autonomy and external-field constraints for ShinY

5.1 ShinY’s online forum and production workflow

After mapping out the offline and online social fields in which fansubbing is located, this section explores the two types of struggle between agents and external social forces in an online non-professional environment. As Bourdieu stresses, the boundary of any field is not fixed and closed. Each field is in a constant flux between two principles and the social dynamics can be examined through the struggle between two poles of autonomy and heteronomy. TakeShinY(http://www.shinybbs.com/) for example.The fansubbing group’s name is literally translated as “deep films” and for several years it has been one of the largest fansubbing communities in China with hundreds of thousands of registered members on the forum and several hundred active subtitlers. The official website ofShinYis in the form of a forum and if we regardShinYas one single online field, five sub-fields can be identified as follows:

1.The ShinY Administration Section(http://www.shinybbs.vip/forum.php?gid=67): This online field can be divided into four sub-fields. The Recruitment section contains recruitment posts for different languages or different positions. Explanation of forum functions for new members can also be found here. The Event Announcement section is used for posting new activities. The Question and Advice section covers questions concerning how to join the group, how to download resources, and other frequently asked questions. The Attendance section functions as a place for members to confirm their everyday attendance every day.

2.The ShinY Original Video Section(http://www.shinybbs.vip/forum.php?gid=36): In this field original videos made by ShinY are presented and ready for members to watch and download.

3.The ShinY News Section(http://www.shinybbs.vip/forum.php?gid=38): News related to American dramas or films are posted here, such as posters of new released films, weekly ratings of dramas or films, gossip news about actors, etc.

4.The ShinY Resource Download Section(http://www.shinybbs.vip/forum.php?gid=68): This field is for downloading. Sub-fields are divided according to the format or resolution (Standard or HD) of the downloading file. Only registered members have access to this section.

5.The ShinY Discussion Section(http://www.shinybbs.vip/forum.php?gid=65): Sub-fields include American Drama Discussion, American Films Discussion, British Drama Discussion, and Other Products Discussion. Members share opinions and discuss dramas or films in this district.

As can be seen from above sections, each of the sub-fields have their specific logic, rules, and tasks that are set by the platform controllers (usually the community leaders). Platform controllers are free to remove or add any notice on the forum, and members may also be given permission to create or delete any sections. This self-governed forum reflects the online fansubbing community’s freedom in controlling and managing its own governance mechanisms. The workflow below is another example displaying the freedom of the structure. Figure 7 displays the typical workflow structure inShinY. The community’s workflow generally follows three processes. The first process is mainly dedicated to the recruitment of newbies and the formulation of the community’s rules. InShinY, the recruits are required to take in-group tests provided by the administrators before participating in a real subtitling project. Only recruits who have successfully passed the tests have the opportunity to be involved in a collaborative work. Recruits who failed in the tests are allocated to work as pre-revisers, engaging in searching for the raw materials or making timecodes for subtitles. As mentioned in the previous section, as administrators are of the highest position in a fansubbing community, they are in charge of the entire recruitment process and have the power to introduce and modify community regulations. The second process usually involves moderators and directors. They function as the intermediaries between the administrators and subtitlers, responsible for selecting translation materials, and allocating and delivering subtitling tasks to members. InShinY, moderators also play the role of supervisors, guiding and advising new recruits on how to complete a subtitling project on time. The third process occupies the most important section and involves fansubbers who are responsible for different parts of the task: pre-revisers, translators, revisers, editors, encoders, and distributors. The three processes of the workflow inShinYdemonstrates that the community has its own patterns from producing a subtitled work to its distribution, implying an autonomous and surrogate demand-supply circulation system (Rong, 2014). The post-production and revising carried out by directors before the distribution is based on the individuals’ own judgments and personal standards, which also lack formal supervision from an authority. The selection and distribution are decided by the community, and members are given the chance to recommend raw materials. Once their recommendations are accepted, the community will initiate a new project. The lack of formal state monitoring and the transmission from passive consumers to active producers fosters them as autonomous agents.

Figure 7. The workflow of fansubbing community ShinY

5.2 External-field constraints for ShinY

In the absence of formal censorship and supervision,ShinYshows a tendency towards self-control and avoidance of copyright infringement for political and legal reasons. Self-control refers to the moral restrictions imposed by the social values between self and context. Figure 8 is the community rules found in the top post on the forum ofShinY. In the context ofShinY, self-control covers the treatments of swearwords, sex-related references, extreme religious expressions, political references, hate speech, and fraudulent behaviours. Violators will be kicked out from the community as punishment. The community rules suggest that group administrators are highly aware of the existence of Internet censorship and potential political risks. Aiming to avoid copyright infringements, the recently uploaded files on the download page ofShinYare merely subtitled files in the format of .it or .txt rather than video files. The heteronomous force from the field of law has now driven fansubbing practice to become an activity taking place within the law by only publishing subtitles.

Figure 8. Screenshot of communication rules on the forum of ShinY

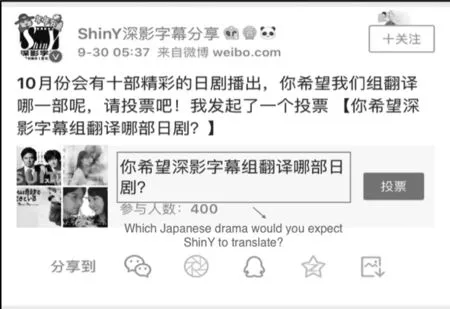

In addition, fansubbing can be treated as representing part of the heteronomous trend of the field given that participants are motivated by market interests. In terms of selecting raw material, the community not only considers members’ recommendations but also has set up a voting system (see Figure 9) on various social media platforms for Internet users to choose the films or TV series they most want to watch. This system ensures that the translated materials can best meet the market expectations. Unlike other commercial practices (e.g. YouTube) which bring monetary rewards and economic capital for the agents, the maximization of market popularity inShinYonly brings symbolic capital to the community through enhancement of its reputation and visibility.

Figure 9. Screenshot of a voting activity on ShinY’s social media page

As Bourdieu stresses, each field and each social agent is driven by the two poles of autonomy and heteronomy. The formal state supervision and high demand for economic capital in the professional subtitling industry illustrates its higher degree of heteronomy as a well-established agent in the field. By contrast, the independent demand-supply chain in fansubbing indicates its inclination to the pole of autonomy. However, with the presence of strict copyright laws and Internet censorship, the burgeoning fansubbing field triggered by advancements in technology has begun to display the influence of heteronomous trends from the political and legal fields.

6. Conclusion

Media and technology have changed our traditional modes of translation. An increasing number of Internet users who have not engaged in formal translation training have come to work as non-professional translators. This article attempts to explore the social position and structures of digitally born nonprofessional subtitling by focusing on one Chinese fansubbing community,ShinY. The analytical tool of Bourdieu’sfield(1985, 2010) and Levina and Arriaga’s (2014) digital sociology makes it compatible to uncover the offline and online fields shaping the production of fansubbing and the capital conversions between the two fields. Specifically, based on the offline and online components of fansubbing, the article reveals that fansubbing can be defined as a sub-field of the offline subtitling field, which is defined by subtitling capital. Similarly, the online component of fansubbing is located in the sub-field of the online field and secured by the accumulation of attention capital. The different roles and position of fansubbers are based on the volume and types of capital acquisition. Moreover, fields are relational. The offline field and online field do not exist independently. There are constant capital conversions ongoing between the two fields. External sources of capital can be converted into online fields (e.g. using translation skills in producing subtitles online). In turn, capital accumulated in online fields can be imported into external capital (e.g. online non-professional subtitlers use the subtitling skills they acquire in the virtual community to develop their offline career). Additionally, the example ofShinYshows that online nonprofessional subtitling enjoys some freedom in the production of subtitles in terms of their self-governed forum and workflow. However, no social activity is purely free from the heteronomous principles derived from the power field.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

翻译界的其它文章

- Constraints and Challenges in Subtitling Chinese Films Into English

- Identity Construction of AVT Professionals in the Age of Non-Professionalism: A Self-Reflective Case Study of CCTV-4 Program Subtitling

- The Subtitling of Swearing in Criminal (2016) From English Into Chinese: A Multimodal Perspective

- Omission of Subject “I” in Subtitling: A Corpus Review of Audiovisual Works

- A Shift in Audience Preference From Subtitling to Dubbing?—A Case of Cinema in Hong Kong SAR, China

- The Development and Practice of Audio Description in Hong Kong SAR, China