Constraints and Challenges in Subtitling Chinese Films Into English

2019-05-12JingHAN

Jing HAN

Western Sydney University / SBS TV Australia

Abstract Globalisation and rapid progress of technologies see the increase of the demand for quicker and more direct access to foreign-language films. Subtitling, as an efficient and economical form of cross-cultural and crosslingual transmission, is set to meet such a demand. While sophisticated computing software has greatly improved the efficiency and accuracy of technical aspects of subtitling, linguistic and cultural challenges in subtitling remain multi-levelled and intriguing. In this paper, the author, basing on her years of practice, explores the concept of subtitling and the various constraints that are intrinsic to subtitling through a detailed analysis of examples selected from eleven subtitled Chinese films, in order to provide guidance to those who are interested in the practice and teaching of subtitling. These constraints differentiate subtitling from standard textual translation, whilst, as this paper argues, presenting heightened challenges in text transfer from a source language and culture to a target language and culture on screen. In the framework of these constraints, key cultural and linguistic challenges in subtitling Chinese films are discussed and subtitling strategies are illustrated in the light of translation as a negotiation, mediation and decisionmaking process.

Keywords: subtitling, constraints, synchronising, equivalence, literalism, Chinese films

1. Introduction

According to Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2007, p. 8), subtitling gained its visibility in the 1990s due to “proliferation and distribution of audiovisual materials in our society” and subtitling has emerged as a most thriving area of studies in the wider discipline of translation studies. Pérez-González (2014, p. 12) supports the view by stating that “audiovisual translation has been the fastest growing strand of translation studies” in the last fifteen years. House (2018, p. 170) calls audiovisual translation “one of the most innovative and fastest growing fields of action for translators worldwide”.

Subtitling is a highly specialised craft and it is quite different from standard textual translation in many aspects. Imposed upon by its unique features, subtitling undertakes the same mission as any other types of translation practices, which is to mediate and facilitate communication between source language content and target language audience, except that the challenges faced in subtitling can be heightened due to the constraints that are intrinsic to subtitling. Subtitling has been defined as “snippets of written text superimposed on visual footage that convey a target language version of the speech” in synchrony with the corresponding dialogue and image (Pérez-González, 2014, pp. 16-17; Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007, pp. 8-9). The task of the subtitler is to render speech into a reading format on a visual medium. The audience needs to read to understand the flow of the story and match what they hear, screen by screen as page by page when reading a book. The transmission is from the source language to the target language and the source culture to the target culture. Therefore, subtitling involves an audio-visual medium and a literary medium all at once. The multimodality of subtitling poses new challenges to translators (House, 2018, p. 170). The shift from a spoken medium to a written medium is termed the “intermodal form” of audiovisual translation (Gottlieb, 1997, p. 95). It is this shift that informs the principal constraints of subtitling and these constraints, which in turn, underpin the development of the conventions in subtitling. Understanding the constraints and related conventions in subtitling are essential for audiovisual translation practice and studies.

The paper will then look specifically at the transmission from the Chinese language and culture to English language and culture in subtitling. The linguistic and cultural differences between Chinese and English add another layer of complexities and challenges in subtitling Chinese films into English. Telling examples selected from eleven subtitled Chinese films are used to analyse some specific circumstances encountered and strategies used in subtitling, which highlights some of the issues that are central to translation as a form of cross-lingual and cross-cultural communication (House, 2009, p. 12).

2. Constraints of subtitling

2.1 Major constraints

Subtitling is governed by three principal constraints (SBS Subtitling Guidelines, 1990): reading speed (duration), spatial constraint, and deprivation of tools used in print media such as footnotes or endnotes to provide explanations of concepts and ideas that do not exist in English.

First of all, people almost always speak faster than they read. The estimated average reading speed for English-speaking viewers is 12 characters per second in Australia, which virtually means that the duration of one second allows only one to two words in the corresponding subtitle. So, the transportation of a spoken medium to a reading medium leaves the subtitling short of time from the outset.

Secondly, the physical size of the medium — being a TV, cinema screen or portable device — can only fit a maximum of two lines of text without cluttering up too much of the screen and impinging on the images.

Thirdly, the deprivation of explanatory tools, such as footnotes, poses a particular challenge in subtitling Chinese films for English viewers. Many cultural concepts, historical references, folk customs, metaphors, and proverbs that appear in Chinese films do not exist in English. For example, in the filmThe Marriage Certificate(Fu & Zhang, producers, Huang, director, 2001), the girl complains that her mother forced her and her dad to search day and night for the lost marriage certificate. She says:

那两天我怎么看我妈都像个地主婆。(4 seconds)

整个就是一个白毛女里的黄世仁他妈。(3 seconds 13 frames)

(literal translation: For those two days my mum was just like a landlord’s wife. She was virtually Huang Shiren’s mother inWhite-Haired Girl.)

A landlord’s wife in Chinese refers to the time before the 1949 Liberation when landlords, as part of the ruling class, oppressed and exploited peasants. A landlord’s wife has become a cultural term which represents a mean-spirited, evil, and cruel woman who relentlessly takes advantage of poor and helpless people. But “a landlord’s wife” in English is a very neutral term without any such evil overtones. “White-Haired Girl” is a well-known folk story in China, later made into a film as one of the “Eight Revolutionary Model Operas” during the Cultural Revolution. In the story, Huang Shiren is an evil landlord, and the white-haired girl is a servant to his mother who treats her brutally. Refusing to become Huang Shiren’s sex slave, the girl escapes and hides in the mountains. A few years later when she is found again by the villagers, her hair has all turned white.

The transmission of culture-specific references within restricted duration and text means some elements have to be compromised, but not the flow of the story. The translation of the two sentences cited above has to be close to the original meaning but must also make sense to viewers. Below is the final version:

To me, Mum looked like

a mean old fishwife.

She reminded me of the evil

man’s mother in that film.

The transposition of a landlady in the specific Chinese context into “a mean old fishwife” enables English-speaking viewers to understand the essence of the Chinese usage of the term through the new contextual relevance accessible to them. The name Huang Shiren which symbolises evil men but embodies no such reference to the target language audience is replaced by the direct expression. The filmWhite Haired Girl, which is unknown to the target language audience, is a representative film in a specific period in Chinese history and known to many Chinese audiences. The choice of “that film” instead of “a film” gives the reference to a particular film.

2.2 Other significant elements in subtitling

Consistency in the flow of subtitles is of paramount importance. Such consistency is created and maintained by accurate time coding. Time coding encompasses in-times, when the subtitle comes in, and out-times when the subtitle goes out. Accurate in-times are vital in subtitling, as they synchronise the subtitle’s appearance on screen with the onset of speech. This synchronisation establishes an immediate link for viewers between what they are reading at that moment and the particular speaker they are hearing. If the subtitle comes in too late or too early, a gap is opened up between the text and the speech to which it refers. Viewers are thrown off balance and the flow of subtitles is broken.

Out-times can be placed later than the point where the speech actually ends to maximise the reading time available for each subtitle. However, if the speech ends on a camera change, the out-time should not be carried over the camera change (SBS Subtitling Guidelines, 1990). Camera changes and scene changes are the other elements which need to be strictly observed in subtitling. The film is an audiovisual medium. Subtitles are processed against the background of a flow of visual images as well as soundtracks. Therefore, it is very important to bring the flow of subtitles into harmony as far as possible with the visual flow.

The flow of subtitles refers to the temporal succession of subtitles on screen. The viewer cannot go back to the previous subtitle while watching a film, as the reader can go back to the previous page while reading a book. Blocking is an effective subtitling tool, which breaks the speech flow into discrete and selfcontained blocks of subtitles according to the rhythm and pauses of the speaker’s delivery. Self-contained blocks mean each block of subtitles should contain either a sentence or a well-defined part of the sentence in terms of meaning and syntactic structure. The same words may have a different meaning or effect depending on how they are blocked. Below is an example.

Subtitle 1:

My mum raised me

after Dad was killed

Subtitle 2:

by becoming a hooker.

This blocking presents an unintended ambiguity or misinterpretation of who became a hooker. However, if the speech is blocked in the following way, it brings the needed clarity to viewers:

My mum raised me

by becoming a hooker

after my Dad was killed.

2.3 Reference to SBS subtitling standards

The Subtitling Department of SBS Television, Australia, has over 30 years of practice in producing world-class English subtitles for non-English films and TV programs. SBS TV provides a multilingual and multicultural broadcasting service to Australian audiences. The mission of SBS TV is to make the world accessible to Australia, and subtitling is the core of this mission. SBS’s Subtitling Unit is one of the largest subtitling departments in the world. The unit has developed practical and high-standard subtitling guidelines and a comprehensive style guide.

Based on the physical size of the screen, each subtitle is limited to a maximum of two lines, so as not to clutter the screen. Each line consists of a maximum of approximately 40 characters including spaces and punctuation. The standard ratios of characters to duration allow a maximum of 40 characters in 3 seconds or 26 characters in 2 seconds. One second is the absolute minimum for any subtitle and is acceptable for only very simple one- to two-word messages. When a subtitle exceeds the standard ratios or has a duration of less than a second, the subtitle will be too fast for the viewer to register and it becomes self-defeating.

A subtitle’s in-time should not precede the onset of speech by more than 6 frames. Leaving subtitles on-screen for 12-18 frames past the end of speech is acceptable so as to maximise the reading time. However, where possible, in-times and out-times should match camera angle changes. Carrying subtitles over the camera change will introduce a mismatch between the flow of the subtitles and the flow of the picture and become visually disruptive.

Apart from accurate timing, effective blocking, and respect for camera changes, word order, and subtitle layout are also important in making subtitles easy to read and take in. How to distribute the text between two lines within a subtitle requires careful consideration of syntactic details. The rule is always to aim for the simplest and least cluttered forms of syntax and layout. Subtitles are easier to read if the line lengths of a subtitle are reasonably similar. A very short opening line followed by a much longer second line should be avoided. However, breaking up a continuous line just to equalise the line lengths should also be avoided. The selection of an appropriate point to break the line is guided by and based on the structure of the speech. Wherever possible, logically linked parts of sentences should be kept together in one line, such as subject and verb, verb and object, article and noun, adjective and noun, preposition and the rest of a phrase, conjunction and the remainder of the sentence.

Based on my own practice and our collective experiences at SBS, we can conclude that the best subtitles are the best possible translations created under all the constraints intrinsic to subtitling. They should effectively convey the meaning of the original speech and they should have high readability without requiring too much mental juggling. To make comprehension of subtitles as written texts instantaneous, subtitles should have grammatical and lexical structures which are as straightforward as possible. Subtitles of high quality do not stand out but rather blend in with the audio and visuals of a film. They are inconspicuous and not visually obstructive or intrusive. In short, subtitles are most effective when they recede into the background of the viewer’s consciousness and are processed effortlessly.

Whilst these constraints on subtitling entail stringent rules to be followed and make subtitling a highly challenging task, they also provide a licence to be creative, as the subtitler, in the end, has to find a solution and such a solution can only be achieved through a creative approach.

3. Differences between Chinese and English

3.1 Typographical differences

Chinese and English are two highly differentiated languages. They share no common linguistic and cultural ancestry. They have completely different syntax, lexical structure, and vocabulary.

As far as subtitling is concerned, Chinese is a very concise language. Being ideograph-based, Chinese takes less space in its written form and shorter duration in its spoken form than English. There are no articles or prepositions in Chinese and there are no singular or plural forms. The verb system in Chinese is much simpler and less “wordy” than that in English. English verbs carry variations to express tenses, to comply with singular or plural forms, or to be in agreement with the subject. Whereas in Chinese, verbs do not change forms. Therefore, the verb “be” is the same character that goes with any nominative cases, such as “I be”, “They be”, “You be”. Also, in Chinese, there are no tenses. Time is simply indicated with temporal adverbs.

Chinese idioms contribute in a significant way to the conciseness of Chinese and are used frequently in both written and spoken Chinese. They are a set of traditional idiomatic expressions, most of which consist of four Chinese characters. The meaning of a Chinese idiom in most cases is not contained in the sum of the meanings carried by the four characters but is derived from a myth, story or historical event. Chinese idioms are highly compact, and one needs to know the story behind a specific idiom to comprehend its meaning.

Another significant difference between Chinese and English which impacts greatly on subtitling is that Chinese is topic-prominent whereas English is subject-prominent (Li & Thompson, 1978). While the subject is central to English, the topic can stand on its own in Chinese. In Chinese “下雨了” (Raining) is a complete sentence, whereas, in English, one has to say, “It is raining”. If a dummy subject such as the “It” in this sentence is absent, the passive voice will be required. For example, 钱还了 (Money return), is short and self-sufficient in Chinese. In English, it has to be “The money has been returned”.

In addition, being a topic-prominent language, Chinese is also a pronoun-dropping language — pronouns can be dropped when they are contextually or pragmatically inferable. Pronoun dropping occurs more frequently in spoken Chinese, particularly in situations where dialogues are informal, or speakers are not educated. In Chinese films such asCrazy Stone(Yu, Zhou & Han, producers, Ning, director 2006) where dialects are used, many dialogues drop pronouns to reflect the casualness and lower level of education of the characters. However, such an informal element in Chinese cannot be conveyed through broken or half-finished English sentences, as that would indicate wrongly that the villagers speak broken Chinese. In this situation, simple and plain English sentences reflect the appropriate register of the original style.

In terms of syntax and structure, English is much lengthier and wordier than Chinese. These typographical differences make the transmission from Chinese into English particularly difficult, in that in most cases Chinese sentences provide less time and space than their English translations would need. Tackling the shortage of time and space is a constant challenge in subtitling Chinese films into English.

3.2 Cultural differences

Chinese culture and history are unique and share few similarities with the culture and history of Englishspeaking countries. Such uniqueness causes great difficulties and challenges in cross-cultural translation and transmission, as often there are simply no equivalents to be found in the English language. Barnstone (1993, p. 40) provides a logical explanation for this: “The target language lacks a word because its culture lacks the experience which gave birth to that word in the source language”.

Difficulties arise not only from vocabulary but also from cultural experiences and concepts that do not exist in the target language. Comprehensive knowledge of Chinese history and culture is absolutely vital in subtitling Chinese films. The period from 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was established to 1978 when the reform and opening-up policy began proves to be particularly tricky for translations. For a period of nearly 30 years, China was virtually cut off from the outside world, particularly the western world. Many political campaigns and movements were instigated, and they shaped the culture and people’s lives over this period in such a unique way that it is often impossible to share those experiences with, or even make them comprehensible to, anyone outside the given period.

The filmThe Blue Kite(Tian, producer and director, 1993) is a very typical example. It tells a story from the perspective of a young boy growing up in the 1950s and 1960s. The period covers three major political movements in Chinese revolutionary history: the Hundred Flowers Campaign, Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution. The story is set in a unique period in Chinese history which shares no similarities with today’s life and in a completely different historical and cultural context. The ideological gap is also reflected in the language containing historical and political terminology that has unique meaning of the time. For example, the literal translation of the speech 那个女孩出生不好 is “That girl didn’t have a good family background.” That, to English speaking viewers, may mean her family is not well-off or she is from a broken family. But the “family background” in the original language is a political term and refers to an individual’s political background or reliability. So the translation such as “That girl has political problems”, indicating she is not trustworthy, is closer to the original reference. In the same film, here is another example which shows that the translator needs to go beyond what is expressed linguistically and bring out the meaning behind that is key to the interpretation of the utterance:

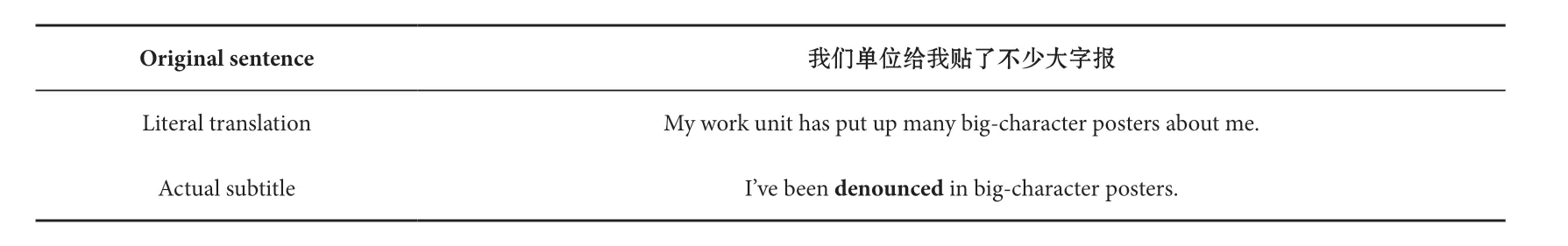

Original sentence 我们单位给我贴了不少大字报Literal translation My work unit has put up many big-character posters about me.Actual subtitle I’ve been denounced in big-character posters.

In the subtitle, the word “denounced” is the key word in explaining what it is meant when one is the subject in big-character posters in the context where the film is set. Or English-speaking viewers may be misled to believe this is a promotion activity in the contemporary context.

Another critically acclaimed film,Balzac and Little Chinese Seamstress(Sijie Dai, producer and director, 2001), also features this theme. The transmission of such a culture-specific event goes beyond a literal understanding of the source language. For example, this dialogue occurs in the film:

- 你说话有城里人口音。(You have a city accent.)

- 我是知青。(I’m an educated youth.)

The translation of “an educated youth” has actually changed the meaning of the original dialogue. A more precise translation would be:

- You have a city accent.

- I’m here for re-education.

Landers (2001, p. 93) observes that “the greater the cultural distance between the source culture and the target culture, the more the translator will need to bridge the gap”. In subtitling Chinese films, finding adequate ways of bridging this cultural and ideological gulf proves to be one of the biggest challenges.

4. Creative transportation vs. literalism

The premise that literalism equals accuracy, and absolute literalism equals absolute accuracy — as well as the notion that absolute accuracy in translation is possible — is absolutely false. (Barnstone, 1993, p. 38)

The term translation, as House (2009) points out, “as an uncountable noun, denotes a process” (p. 974). Umberto Eco in his bookMouse or Rat – Translation as Negotiationdescribes translation as a negotiation process in which in order to get something, one has to give away something else, as one cannot have everything (2004, p. 6). Translation as a process involves “a complex series of problemsolving and decision-making operations” (House, 2009, p. 75). Gutt (1991, p. 21) who sees translation from communication’s point of view rejects the encoding-decoding translation model and argues that there is no direct act of communication between the source language and target language. Translation as a form of communication involves an interpretive process (ibid, p. 24) and translation text interpretively resembles the original text (ibid, p. 100). Such a view is backed up by Eco who states that a translator should aim to render the intention of the text and the intention of text is “the outcome of an interpretative effort on the part of the translator” (2004, p. 5). As seen below, subtitling as a translation practice requires interpretation, negotiation, and mediation in order to achieve cross-cultural and cross-lingual communication.

4.1 Intelligent condensing

Given the time and spatial constraints in subtitling, condensing is not only necessary but also an essential tool in keeping up with the flow of the story. Condensing does not mean simply cutting dialogues short or finding shortcuts by omissions. It weighs up all sorts of alternatives to pin down the most expressive and concise form to convey the original meaning. The guiding principle is that it is the amount of time available for each subtitle that determines the degree of condensation necessary, and not vice versa. In practice, verbal redundancy is avoided, and the visuals are used to supplement the verbal.

One of the most challenging Chinese films to subtitle isHeroby Zhang Yimou (Zhang, producer and director 2002). The story is set around 221 BC. All the dialogues are written in the style of Classical Chinese (文言文), which is much more concise and compact than modern Chinese. Classical Chinese has a unique syntax in which subjects, verbs and objects are often dropped when the meaning is inferred. The extensive use of literary and cultural allusions and Chinese idioms also contributes to its brevity. Furthermore, the film is superbly made, with every single shot scrupulously edited. Concise exchanges are neatly placed in shots finely cut between camera changes, giving the dialogue a crisp and rhythmic feel. However, this also means that the time available for each subtitle is severely restricted by camera changes and often there is no room for expanding the time. Condensing dialogues is required throughout the film. The table below is an example to show how much condensing is required.

(2:20 = 2 seconds 20 frames)

Chinese Speech duration Literal Translation Subtitled Version十年来从未有人上殿近寡人百步。 4:04 For the past ten years, no one has ever been allowed to be within 100 paces of me.For ten years, no one has been within 100 paces of me.可知为何? 1:15 Do you know why? Do you know why?刺客猖獗。 2:01 The assassins were active and lurking around. The assassins were on the loose.不错,刺客一日不除,我难解甲胄。 3:15 That is right. As long as the assassins are around, I am confined in this armour.Correct! That is why I cannot remove this armour.如今你替寡人除此大害。 3:04 Now you have got rid of this big peril for me. Now you have eliminated the peril for me.要何封赏? 2:02 What kind of reward would you like to request? Name your reward.为秦杀贼,不求封赏。 2:21 I killed the traitors for the Qin Kingdom. I didn’t do it for a reward.I did it for Qin, not for a reward.大秦之下,必有封赏。 2:17 Achievements must be rewarded. This is how I rule the kingdom.Under my rule there must be rewards.

Interestingly, the filmCrouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon(Kong, Hsu and Lee, producers, Lee, director, 2000) which is quite similar toHeroin style and content (both stories are about warriors and swordsmanship in ancient China), is quite different in language.Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragonuses vernacular Chinese instead of Classical Chinese. The speech style is rather conversational and modern language usages appear frequently in the dialogues. In that sense,Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragonis much easier to subtitle thanHero.

The key to intelligent condensing is to preserve the essence of the original meaning. To achieve this requires a thorough comprehension of the source language and a keen ability to identify the key messages in the context. Below are some condensing strategies I have used in subtitling.

4.1.1 Dismantle the original sentence structure and re-shape it to convey the key meaning

Chinese Speech duration Literal Translation Subtitled Version先父留下遗愿求贵馆一幅宝墨。 3:19 My father left a will when he died. He wished to acquire a calligraphy scroll from your school.My late father wished to acquire a calligraphy scroll.书法剑术都靠手腕之力与胸中之气。 3:18 Both calligraphy and swordsmanship rely on the strength of the wrist and spirit in the chest.Both brush and sword rely on strength and spirit.就是上天入地,拆房子扒墙,我也得把它找出来。3:02 2:12 Even if I have to go up to the sky or down into the earth, or pull down the house and dismantle the wall, I must find it.Even if I have to turn the flat upside down, I must find our marriage certificate.了。你和我爸且过呢。 4:09 A couple who fight all the time won’t get a divorce. You and Dad will always live together.A fighting couple like you two will never get a divorce.他找了小老婆啦,不回整天吵嘴的夫妻离不来啦。 2:08 He has got himself a mistress and won’t come back. He’s living with his mistress.回去就回去啦? 3:06 Is the school run by you and you can go back to school whenever you want to?The school isn’t run by you or for you.和尚不念经跑到这里开学校是你家开的,你想荤,也该教训。 2:12 A monk who, instead of reciting scriptures, is here eating meat, needs me to teach you a lesson.A meat-eating monk needs a lesson.

4.1.2 Create shorter alternatives but maintain the same meaning

Chinese Speech duration Literal Translation Subtitled Version我比你晚了一步。 1:21 I was later than you by one move. You were faster.别关灯。 1:16 Don’t turn it off. Leave it on.跟咱们矿上没有任何关系。 1:20 It has nothing to do with us. We aren’t responsible.一进他那屋就往外轰。 2:11 Whenever we went into his room, he’d push us out. We weren’t allowed into his room.做一个人人都佩服的演员。 2:19 Be an actor who everyone admires. Be the most admired actor.让他抽死去。 2:04 Let him take drugs until he dies. Let drugs claim his life.我姑姑一把年纪了,还特别挑剔。 2:17 Old as she is, my aunt is very fastidious. My aunt is a fastidious old lady.

4.1.3 Avoid verbal redundancy and omit the information that is contextually inferred or incidental to the narrative

Chinese Speech duration Literal Translation Subtitled Version够,你还折腾他们? 3:02 It wasn’t enough to pester me, you had to pester them as well? Did you have to pester them as well?你折腾我一个人还不你要想聊的话咱们就接着聊,不想聊的话你就可以出去了。2:13 2:07 We can keep talking if you like.If you don’t want to, you can get out.We can keep talking if you like. Otherwise, you can get out.五瓶才成。 3:12 Three bottles were just right for him, but he wouldn’t stop until he’d drunk five bottles.三瓶正好,他非要喝道了一次。 2:24 You won’t win even if you’re struck dead eight times by lightning.雷劈死你八次你也中不有苦劳也有疲劳。 2:20 Even if I didn’t achieve anything, I tried hard. Even if I didn’t try hard, I shed sweat.没有功劳也有苦劳,没He’d go on until he couldn’t take any more.You won’t win even if you die eight times.Even when I failed, I tried and sweated.居。 2:02 We came from the same town and were neighbours since we were little.我们是同乡,从小是邻We used to be neighbours.

4.2 Wordplay and puns

Puns, wordplay, and parodies are often used in films to create comic effects or intellectual games. They pose one of the greatest challenges to subtitling, or to translation in general. As Landers (2001, p. 110) observes, “Many if not most puns will be untranslatable, but the effect can often be reproduced by transferring the wordplay into a different setting in the same text”.

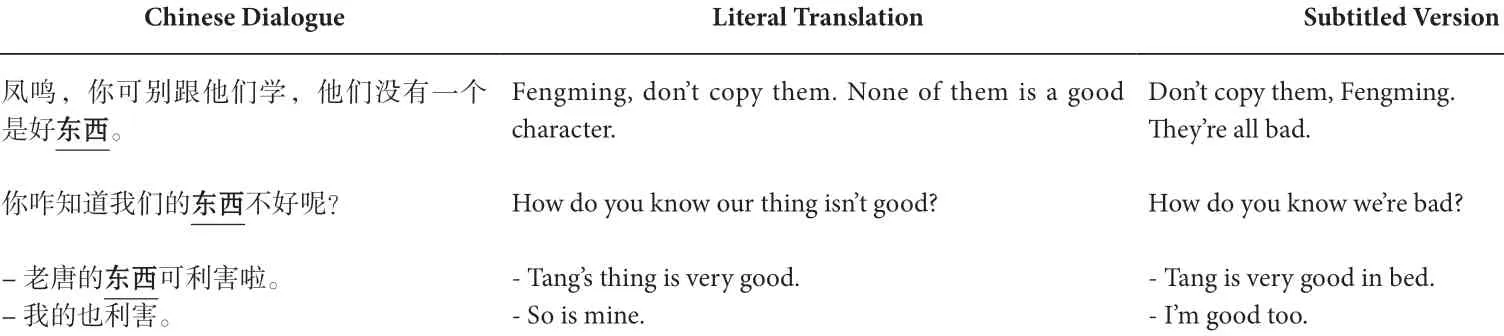

In the filmBlind Shaft(Li, producer and director, 2003), a group of miners make a dirty joke with the young landlady, using a pun on “东西” (dong xi). In Chinesedong xi, when referring to a person, means a bad character or bad behaviour. In a neutral context, it simply means a thing or an object.

Chinese Dialogue Literal Translation Subtitled Version凤鸣,你可别跟他们学,他们没有一个是好东西。Fengming, don’t copy them. None of them is a good character.Don’t copy them, Fengming. They’re all bad.你咋知道我们的东西不好呢? How do you know our thing isn’t good? How do you know we’re bad?- 老唐的东西可利害啦。- 我的也利害。- Tang’s thing is very good.- So is mine.- Tang is very good in bed.- I’m good too.

InQuitting(Loehr, producer, Zhang, director, 2002), the son is very critical of his father’s local accent and insists that he speaks proper Mandarin. In this following dialogue, the father constantly uses the phraseza zhengwhich is a colloquial usage in the northeast and instantly gives away his origin and indicates his lack of cosmopolitan linguistic sophistication. So the choice of the English translations needs to show the contrast between the father’s regional accent and the son’s standard expression of the same term.

Chinese Dialogue Subtitles父亲:这事可咋整呀? Father: How do I handle it?儿子:以后别老说这事可咋整。 Son: Don’t say “How do I handle it?”你试着说说着这事该怎么办。 Say “What should I do about it?”

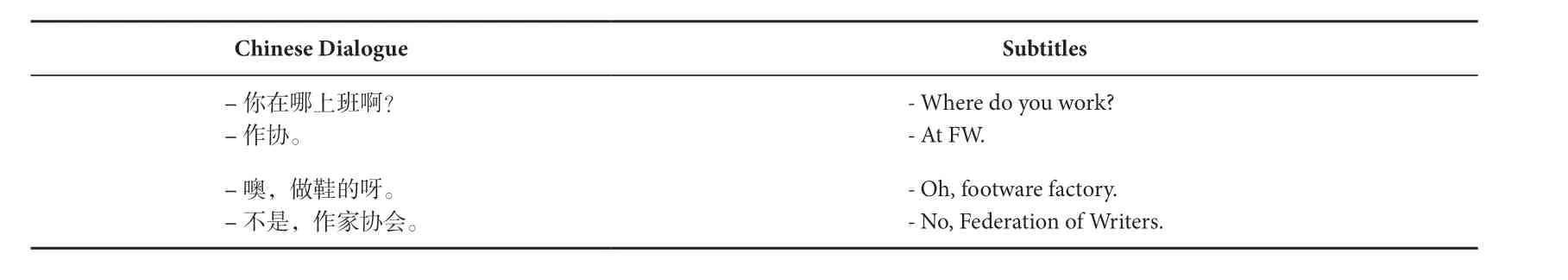

Homonym is often used in Chinese for comic effects and is most difficult to copy in English. For example, 作协zuo xie(Writers’ Association) is a homonym for 做鞋zuo xie(making shoes). In the comedyStand Up, Don’t Bend Over(Huang, producer and director, 1993), a writer moves into a new apartment. His next-door neighbour is a thug. Here is the dialogue when they first meet:

Chinese Dialogue English Translation without Intervention- 你在哪上班啊?- 作协。- 噢,做鞋的呀。- 不是,作家协会。- Where do you work?- At the Writers’ Association.- Oh, footware factory.- No, the Writers’ Association

The intended comic effect which plays on the incongruity of the thug’s ignorance and the writer’s intellectual superiority is lost in this translation which breaks the link between “shoe making” and “writers’ association” in Chinese. A creative solution can be found in the following subtitles:

Chinese Dialogue Subtitles- 你在哪上班啊?- 作协。- Where do you work?- At FW.- 噢,做鞋的呀。- 不是,作家协会。- Oh, footware factory.- No, Federation of Writers.

The use of abbreviation works well in this case.

Some homonyms simply cannot be transferred. In the black comedyCrazy Stone, a newly rich property developer’s treasured BMW is crashed. He points at his car and says “Bie-Mo-Wo” in pinyin, which means “don’t touch me”. This just cannot be mirrored in English. Therefore, I leave it as “This is a BMW”. In this particular situation, this alternative is adequate, as it is a common knowledge that BMWs are expensive cars and should not be freely “touched”.

4.3 Culture-specific references

In cross-cultural and cross-lingual transmission, we try to find equivalence between the source language and the target language. But as Barnstone (1993, p. 18) points out, there is no equivalence without difference and equivalence does not signify replication.

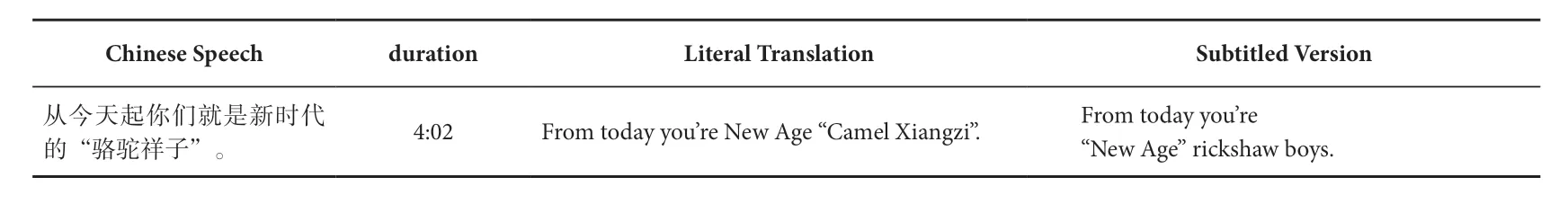

Many cultural and historical terms and concepts in Chinese would make no sense if translated literally. The approach that I have adopted in my practice is to highlight the essence of the concept or reference and omit specific referential information which will not register with the English viewers. InBeijing Bicycle(Chiao, Hsu and Han, producers, Wang, director, 2001), the manager of a courier company tells his employees:

Chinese Speech duration Literal Translation Subtitled Version从今天起你们就是新时代的“骆驼祥子”。 4:02 From today you’re New Age “Camel Xiangzi”. From today you’re “New Age” rickshaw boys.

Camel Xiangzi is a well-known literary character in China, coming from a famous novel by Lao She. Xiangzi is a rickshaw boy. Camel is his nickname because he works hard and is quiet like a camel. The image of rickshaw boys resonates well with the courier boys in the film.

In the same film, there is also a reference to a highly popular Chinese filmThe Story of Qiu Juby Zhang Yimou (Feng and Ma, producers, Zhang, director, 1992). Qiu Ju, a simple country woman, refuses to give up until justice is done for her husband’s injury.

Chinese Speech duration Literal Translation Subtitled Version我说你们那儿的人是不是都有点“秋菊打官司”的劲?3:02 Is everyone from your home village like what is shown in “The Story of Qiu Ju”?Are all you country folk so pigheaded?

However, important referential information can be lost in translation. For example, inCrazy Stone, the playboy Xiaomeng tries all sorts of tricks on his dad to get his money and openly enjoys doing it. He tells his friend:

Chinese Speech Subtitled Version与爹斗其乐无穷。 Fighting with my dad brings me endless pleasure.

This is, in fact, a parody of what Chairman Mao allegedly said: “Fighting with people brings me endless pleasure”. Without the assistance of a footnote, this cleverly crafted message cannot be conveyed. However, in the original script, this allusion is not meant for translation but plays to the assumed knowledge of the audience. If the assumed knowledge is not there, then perhaps it should not become incumbent upon the subtitler to find a substitute.

5. Conclusion

A translated text should be the site where a different culture emerges and a reader gets a glimpse of a cultural other (Venuti, 1995, p. 306).

Subtitling is a unique form of translation which involves multimodality and is transparent in the sense that its source language speech and target language translation appear and become accessible to the audience at the same time. The challenges highlighted and heightened by the constraints that are intrinsic to subtitling can only be understood and tackled effectively within the framework of subtitling conventions. The fundamental challenge in translation stems from the fact that “symmetry between languages hardly exists beyond the level of vague approximations” (Snell-Hornby, 1988, p. 22). As we can see above, it requires a great deal of negotiation on both linguistic and cultural levels to render Chinese speech into English text whilst in synchronisation with the audio and visual flow on the screen. As Eco (2004, p. 123) points out, any translation is an interpretation but not all interpretation is a translation. Obliged as a subtitler is to choose a particular word or sentence, they are bound to leave other possibilities or alternatives unexpressed. Such a choice, in subtitling Chinese films, depends on many factors, including the balance between foreignisation and domestication, between maintaining the Chinese flavour where possible, even sometimes just to register the difference and otherness, and ensuring that the translation is comprehensible to the English-speaking audience. Achieving such a balance is key to the success of translation as a cross-lingual and cross-cultural endeavour.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

翻译界的其它文章

- A Sociological Investigation of Digitally Born Non-Professional Subtitling in China

- The Development and Practice of Audio Description in Hong Kong SAR, China

- A Shift in Audience Preference From Subtitling to Dubbing?—A Case of Cinema in Hong Kong SAR, China

- Omission of Subject “I” in Subtitling: A Corpus Review of Audiovisual Works

- The Subtitling of Swearing in Criminal (2016) From English Into Chinese: A Multimodal Perspective

- Identity Construction of AVT Professionals in the Age of Non-Professionalism: A Self-Reflective Case Study of CCTV-4 Program Subtitling