Colon perforation due to antigenemia-negative cytomegalovirus gastroenteritis after liver transplantation: A case report and review of literature

2019-05-08TakahiroYokoseHideakiObaraMasahiroShinodaYutakaNakanoMinoruKitagoHiroshiYagiYutaAbeYoheiYamadaKentaroMatsubaraGoOshimaShutaroHoriShoIbukiHisanobuHigashiYukiMasudaMasanoriHayashiTakehikoMoriMihoKawaidaTakumiFujimuraKenH

Takahiro Yokose, Hideaki Obara, Masahiro Shinoda, Yutaka Nakano, Minoru Kitago, Hiroshi Yagi, Yuta Abe,Yohei Yamada, Kentaro Matsubara, Go Oshima, Shutaro Hori, Sho Ibuki, Hisanobu Higashi, Yuki Masuda,Masanori Hayashi, Takehiko Mori, Miho Kawaida, Takumi Fujimura, Ken Hoshino, Kaori Kameyama,Tatsuo Kuroda, Yuko Kitagawa

Abstrac t BACKGROUND Cytomegalovirus (CMV) remains a critical complication after solid-organ transplantation. The CMV antigenemia (AG) test is useful for monitoring CMV infection. Although the AG-positivity rate in CMV gastroenteritis is known to be low at onset, almost all cases become positive during the disease course. We treated a patient with transverse colon perforation due to AG-negative CMV gastroenteritis, following a living donor liver transplantation (LDLT).CASE SUMMARY The patient was a 52-year-old woman with decompensated liver cirrhosis as a result of autoimmune hepatitis who underwent a blood-type compatible LDLT with her second son as the donor. On day 20 after surgery, upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy (GE) revealed multiple gastric ulcers and transverse colon ulcers. The biopsy tissue immunostaining confirmed a diagnosis of CMV gastroenteritis. On day 28 after surgery, an abdominal computed tomography revealed transverse colon perforation, and simple lavage and drainage were performed along with an urgent ileostomy. Although the repeated remission and aggravation of CMV gastroenteritis and acute cellular rejection made the control of immunosuppression difficult, the upper GE eventually revealed an improvement in the gastric ulcers, and the biopsy samples were negative for CMV. The CMV-AG test remained negative, therefore, we had to evaluate the status of the CMV infection on the basis of the clinical symptoms and GE.CONCLUSION This case report suggests a monitoring method that could be useful for AGnegative CMV gastroenteritis after a solid-organ transplantation.

Key words: Cytomegalovirus gastrointestinal disease; Colon perforation; Antigenemia negative; Liver transplantation; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Although cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection can remain latent since childhood, it can be reactivated due to immunosuppression. While CMV gastroenteritis presents with clinical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and melena, a definitive d iagnosis is mad e based on end oscop ic find ings and the histopathological examination of biopsy tissues. The CMV-antigenemia (AG) positivity rate at the onset of gastroenteritis has been reported to be approximately 20%-30%[1]. Although gastrointestinal perforation due to CMV gastroenteritis is not uncommon[2], such an occurrence has rarely been reported after organ transplantation[3]. Autoimmune hepatitis is an autoimmune disease that commonly develops in middle-aged or older woman and usually causes chronic and progressive liver damage. In regard to treatment, immunosuppressants, especially prednisolone, are commonly used. Liver transplantation is the final therapeutic option for patients, such as in a recently reported case on a patient with autoimmune hepatitis who developed decompensated cirrhosis due to an insufficient response to medical treatment.

We managed a p atient w ith a comp licated condition, w ith transverse colon perforation that was caused by AG-negative CMV gastroenteritis, after a living donor liver transplantation (LDLT). Here, we report on this case, w hich was difficult to diagnose and treat.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Abdominal pain and fullness.

History of present illness

The p atient w as a 52-year-old Asian w oman, w ho w as d iagnosed w ith liver d ysfunction d uring a med ical examination in her tw enties. A d iagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis w as mad e at 40 years of age. When the patient w as 46 years old, the patient developed ascites, which improved with oral steroids. How ever, w ith disease progression, she d eveloped decompensated cirrhosis at 51 years old that was resistant to medical management. She was then referred to our department.

History of past illness

There was no other significant medical history.

Personal and family history

The patient was a nonsmoker and had stopped drinking socially 5 years prior. Her occupation was a housewife. There was no relevant family history.

Physical examination upon admission

According to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, her performance status was 2. At the physical examination, the patient's height was 155 cm, her weight was 47 kg, and her vitals were stable; yellowish bulbar conjunctivae,ascites, and bilateral pedal edema were observed.

Laboratory examinations

The Child-Pugh score was 11 points in class C, and the Model for end stage liver disease score was 11 points. The serologic tests for CMV showed that the patient was IgG positive (+), IgM negative (-), and AG negative, which is indicative of past CMV infection. A PCR test for CMV was not performed routinely before transplantation at our facility and was not performed in this case.

Imaging examinations

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed liver cirrhosis with ascites before LDLT.

Liver transplantation and follow-up

A blood-typ e compatible LDLT w as p erformed using a left lobe graft, w ith the patient's second son as the donor (20 years old, CMV IgG+/IgM-, w hich is indicative of past CMV infection). The graft-to-recipient w eight ratio w as 0.73, the op eration d uration w as 849 min, and the bleed ing volume w as 822 m L. At our facility, in accord ance w ith the p rotocol of CMV monitoring and treatment after a liver transp lantation, CMV-AG is tested tw ice a w eek, but a CMV-PCR test is not performed routinely. In addition, prophylactic ganciclovir (GCV) is not administered,but GCV is initiated w hen the patient becomes CMV-AG positive or in the case of a seropositive donor.

Initially, cyclophosphamide (Cy A), pred nisolone (PSL) and mizoribine (MIZ) w ere used as the postoperative immunosuppressants, in accord ance w ith the protocol of our facility[4,5], however, for this patient, MIZ w as replaced by mycophenolate mofetil(MMF) due to pancytopenia, and Cy A was replaced by tacrolimus (FK) due to renal failure. As the patient had jaundice and persistently elevated aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase levels, a liver biopsy w as performed on the 10thd ay after transp lantation. The histop athological examination w as negative for both acute cellular rejection (ACR) and CMV hepatitis, so her cond ition w as susp ected to be drug-induced or caused by cholestasis.

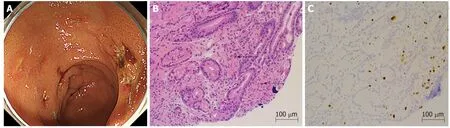

Starting on the 12thd ay after transplantation, the patient's anemia w orsened, and she required frequent packed red blood cell transfusions. Further investigations confirmed thrombocytopenia, jaundice, and renal failure. We susp ected thrombotic microangiop athy (TMA), even though the p erip heral smear w as negative for fragmented red blood cells, and a fresh frozen p lasma transfusion and FK d ose reduction w ere carried out. The CMV-AG remained negative, and there w ere no clinical find ings that w ere characteristic of a CMV infection, but prophylactic GCV administration w as initiated. Thereafter, the thrombocytopenia gradually improved.On the 20thday after transplantation, the patient reported abdominal pain and blackcolored stools, so up per gastrointestinal endoscopy w as performed, w hich show ed multiple gastric ulcers (Figure 1A). A biopsy tissue samp le, taken from an ulcer,show ed large cells w ith intranuclear inclusions w ith hematoxylin and eosin (HE)staining (Figure 1B), and CMV-positive cells w ere observed through immunostaining(Figure 1C). Once the diagnosis of CMV gastroenteritis w as confirmed, GCV, w hich had alr ead y been in itiated, w as con tinu ed, an d the d osage of all 3 immunosuppressants, FK, PSL, and MMF, was reduced.

Figure 1 Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and tissue biopsy diagnosis. A: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed multiple gastric ulcers in the vestibular area. B: Biopsy tissue diagnosis showed large cells with intranuclear inclusions on hematoxylin and eosin staining (arrows) (× 200). C: Cytomegalovirus positive cells were observed through immunostaining (× 200).

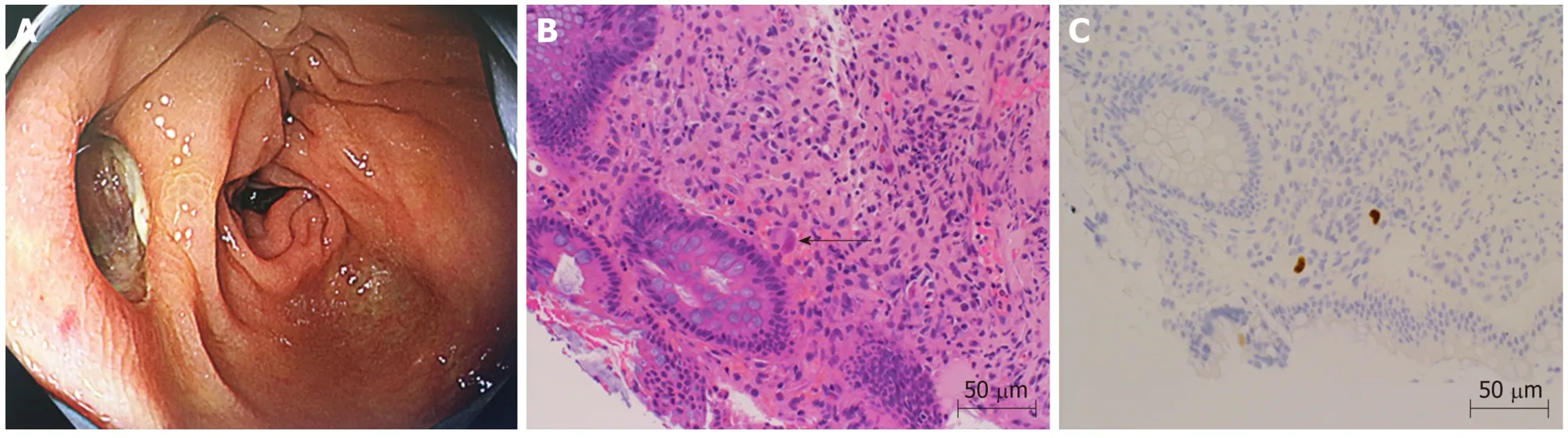

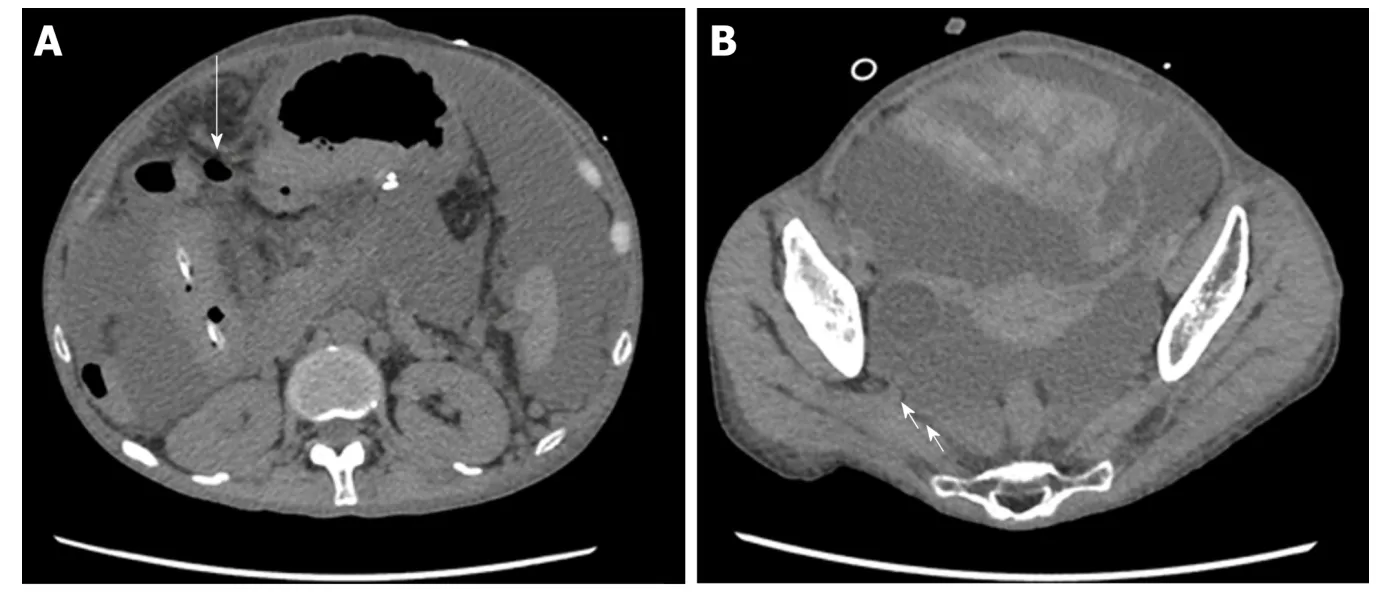

On the 26thday after transplantation, the patient had frequent, w atery diarrhea, for w hich a low er gastrointestinal end oscop y w as p erformed, and a d eep ulcer w as observed in the transverse colon (Figure 2A). The biopsy tissue d iagnosis of the ulcerative lesion revealed large cells with intranuclear inclusions with HE-staining(Figure 2B) and CMV-positive cells with immunostaining (Figure 2C). On the 28thday after transplantation, we noted the findings of abdominal pain, fever and an increased inflammatory response. A plain abdominal CT scan revealed intraperitoneal free air adjacent to the transverse colon (Figure 3A) and hemorrhagic ascites in the pelvis(Figure 3B).

The patient was diagnosed with gastrointestinal perforation, and an emergency surgery was performed. When the abdomen was incised, contaminated ascites were not observed. In the transverse colon, an impending perforation with a thinned serous membrane was confirmed.

The rejection activity index score of the liver tissues collected during the surgery was found to be P2, B1, and V1 during the histopathologic examination, indicating ACR.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final d iagnosis of the p resented case w as transverse colon p erforation d ue to CMV gastroenteritis.

TREATMENT

GCV was administered for CMV gastroenteritis.

During the emergency surgery, as it was difficult to remove the adhesions with the surrounding areas, thus, the site of perforation was left as it was. Simple lavage with drainage was performed, and ileostomy was performed for acute pan-peritonitis due to transverse colon perforation.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The repeated remission and aggravation of CMV gastroenteritis, ACR and TMA made the control of immunosuppression extremely difficult. CMV-AG remained negative throughout the disease course, but the CMV-PCR test result was 220 copies/mL. On the 46thday after transplantation, a follow-up upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed that the gastric ulcer w as finally resolving, and the biopsies were also negative for CMV. The patient was ambulatory at discharge on the 86thday after transplantation.

DISCUSSION

Although CMV infection is often contracted in childhood, it usually remains latent. It is often reactivated due to immunosuppression after an organ transplantation[6]. Most Jap anese ind ivid uals are infected w ith CMV in early child hood s, and it usually remains latent. Therefore, even if a donor candidate had a past CMV infection, he or she is not excluded as a donor. When the recipient is seronegative w hile the donor is seropositive for the CMV antibod y, the risk of onset of CMV infection after organ transplantation is high, and appropriate monitoring and prophylactic measures are necessary[7]. How ever, w hen the recipient is seropositive, whether the recipient is at risk of infection w hen the donor is seropositive or seronegative is controversial.

Figure 2 Lower gastrointestinal endoscopy and tissue biopsy diagnosis. A: Lower gastrointestinal showed a deep ulcer in the transverse colon. B: Biopsy tissue diagnosis showed large cells with intranuclear inclusions on hematoxylin and eosin staining (arrow) (× 400). C: Cytomegalovirus positive cells were observed through immunostaining (× 400).

The d iagnostic method s for CMV includ e (1) the isolation and id entification of CMV from blood, urine and p haryngeal secretions; (2) the CMV-AG test, w hich involves the d etection of CMV-antigen-positive p olymorp honuclear leukocytes in peripheral blood using a monoclonal antibod y; (3) the CMV-PCR method, w hich involves amplifying CMV-DNA from blood and the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for the identification; and (4) cytopathological and histopathological examinations, w hich involve the evaluation of the target organs of CMV infection w ith endoscopy and biopsy to detect the intranuclear inclusion bodies of giant cells through HE staining and CMV antigens through immunostaining using an anti-CMV monoclonal antibod y[6,7]. Because both the sensitivity and sp ecificity of the CMV-AG test are rep orted to be 70%-90%[8,9]and the levels are ind icative of d isease severity and treatment response, the test is said to be effective for infection monitoring. The CMVAG test is therefore used as an ind icator for the initiation and comp letion of treatment. The sensitivity and specificity of the CMV-PCR method are reported to be superior to the CMV-AG test[10-14], and w hile a quantitative estimation of the number of copies is possible with the former, the positive cut-off value varies among different reports[9-11,13,15]. The CMV-PCR test is not covered by health insurance providers in Japan.

CMV gastroenteritis exhibits clinical symp toms such as nausea, vomiting,abd ominal pain and melena, and it is characteristic to find multiple gastrointestinal ulcers during end oscop y[6,10,15]. The diagnosis is based on endoscopic find ings and biop sy tissue examination and analysis. The d iagnosis is confirmed w hen the intranuclear inclusion bod ies of giant cells are observed using HE stains and CMV antigens are identified through immunostaining[6,10,14,16]. When an ulcerative lesion is observed in the gastrointestinal tract of an immunosuppressed patient, the site should be biopsied and investigated, keeping CMV infection in mind. Although it has been reported that in CMV gastroenteritis, the CMV-AG positive rate is approximately 20%at onset and that false-negatives results occur frequently[1], the CMV-AG status becomes positive in most cases d uring the disease course, thus making this test a useful parameter for monitoring the response to treatment[1,8,14,17]. While there have been reports on rare cases in which patients who had CMV gastroenteritis had CMVAG results that remained negative throughout the d isease course after bone marrow transplantation[13,18,19], there have been no such reports associated w ith solid-organ transplantation; how ever, there have been some reports in w hich the CMV-AG test was positive when an intestinal perforation w as caused by CMV gastroenteritis[20,21],including a report in which intestinal perforation were caused by CMV gastroenteritis in patients taking immunosuppressants to treat rheumatoid arthritis[2]. Although it has been reported that routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy during the follow-up for CMV gastroenteritis does not lead to differences in recurrence rates and treatment effects[17], there are also cases such as ours, w here the patient suffers from localized CMV infection but d oes not achieve viremia and remains CMV-AG negative throughout the d isease course. An examination of symptomatic p atients through regular up p er gastrointestinal end oscop y and biop sy may be an imp ortant monitoring method, and it is necessary to tailor the medical management on a case-tocase basis.

Figure 3 Abdominal computed tomography images. A: Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed intraperitoneal free air near the transverse colon (arrow). B: Abdominal CT revealed hemorrhagic ascites in the pelvis(arrow).

Although there have been reports on cases with gastrointestinal perforation due to CMV gastroenteritis, this complication is extremely rare after a solid organ transplantation[2,3]. Recently, there was a report showing that CMV infects vascular endothelial cells and causes ulcers and perforation locally in the intestinal mucosa after solid-organ transplantation[21].

In our case, in ad d ition to the long-term history of oral PSL therap y for au toim m u n e h ep atitis befor e tr an sp lantation, p osttr an sp lantation immunosuppression was essential. This may have caused CMV gastroenteritis with strong, localized inflammation that led to intestinal perforation without viremia.

Although CMV infection tends to occur at least three week after transplantation[3],patients taking immunosuppressive drugs before transplantation may be affected earlier[6].

Atsumi et al[22]and Kemeny et al[23]have reported on patients presenting with a combination of polyoma virus infection and acute graft rejection after kidney transplantation. However, the coexistence of an infection and rejection represents a combination of contradictory illnesses and constitutes a rare presentation. In our case,the p atient w as first d iagnosed w ith ACR through an intraoperative liver biopsy sample taken during the emergency procedure for gastrointestinal perforation in an advanced stage of CMV infection. It was a combination of an infection and a rejection,which again is an extremely rare presentation, which made the management difficult.

TMA is a condition in which polymers of von Willebrand factor are secreted due to vascular endothelial cell dysfunction that is caused by various factors, for e.g., graftversus-host disease (GVHD), ABO-incompatible transplantation, calcineurin inhibitor(CNI) administration, and fungal and viral (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus,CMV and adenovirus) infections[24,25]. This secretion promotes platelet thrombus formation, leading to multiorgan failure due to microangiopathy. Although the recommended criteria for diagnosing TMA have been previously reported, there are no set diagnostic criteria. Our hospital, as reported previously[26], follows the protocol of a d iagnosis based on clinical examination findings and the app earance of fragmented red blood cells in the peripheral smear, combined with tests showing hemolytic anemia, thrombocytop enia and increased bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase levels.

CMV has been reported to exhibit a TMA-like disease state by infecting vascular endothelial cells and making them dysfunctional[27,28]. Java et al[29], Waiser et al[30]reported a patient w ith newly developed TMA due to CMV infection in a kidney transplant recipient. In our case, treatment with GCV was initiated as the patient presented with symptoms of TMA prior to the detection of CMV infection. Therefore,a CMV infection could be suspected in a TMA-like disease presentation.

In patients who are chronically treated with immunosuppressants before organ transplantation, endoscopy should be performed according to symptoms at an earlier stage after transplantation. As a reliable test, the CMV-PCR test is reported to be superior to the CMV-AG test, but it is not covered by health insurance providers in Japan.

CONCLUSION

After solid-organ transplantation, it is necessary to monitor symptomatic patients for CMV gastroenteritis, even when the CMV-AG assay remains negative throughout the course of the illness. Ad d itionally, a CMV infection should be suspected w hen a TMA-like disease presentation is observed, and the p atient should be investigated accordingly, to rule out this diagnosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge Mr. Gotou Masaki (Department, LSI Medience Corporation) for advice on the antigenemia assay evaluation.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Repurposing drugs to target nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- Central role of Yes-associated protein and WW-domain-containing transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif in pancreatic cancer development

- Considerations of elderly factors to manage the complication of liver cirrhosis in elderly patients

- Lysyl oxidase and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α: biomarkers of gastric cancer

- Predictive and prognostic implications of 4E-BP1, Beclin-1, and LC3 for cetuximab treatment combined with chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer with wild-type KRAS: Analysis from real-world data

- Extract of Cycas revoluta Thunb. enhances the inhibitory effect of 5-f luorouracil on gastric cancer cells through the AKT-mTOR pathway