Antihydatic and immunomodulatory effects of Punica granatum peel aqueous extract in a murine model of echinococcosis

2016-07-24MoussaLabsiLilaKhelifiDalilaMeziougImeneSoufliChafiaTouilBoukoffaLaboratoryofCellularandMolecularBiologyDepartmentofBiologyUniversityofSciencesandTechnologyHouariBoumedieneAlgiersAlgeria

Moussa Labsi, Lila Khelifi, Dalila Mezioug, Imene Soufli, Chafia Touil-BoukoffaLaboratory of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Department of Biology, University of Sciences and Technology Houari Boumediene, Algiers, Algeria

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Antihydatic and immunomodulatory effects of Punica granatum peel aqueous extract in a murine model of echinococcosis

Moussa Labsi, Lila Khelifi, Dalila Mezioug, Imene Soufli, Chafia Touil-Boukoffa*

Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Department of Biology, University of Sciences and Technology Houari Boumediene, Algiers, Algeria

ABSTRACT

Objective: To investigate the effect of pomegranate peel aqueous extract (PGE) on the development of secondary experimental echinococcosis and on the viability of Echinococcus granulosus protoscoleces, and the immunomodulatory properties of PGE. Methods: Swiss mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with viable protoscoleces. Then, PGE was orally administered daily during cystic echinococcosis development. Cyst development and hepatic damage were macroscopically and histologically analyzed. The production of nitric oxide and TNF-α was assessed in plasma and the hepatic expression of iNOS, TNF-α, NF-κB and CD68 was examined. Moreover, protoscoleces were cultured and treated with diff erent concentrations of PGE. Results: It was observed that in vitro treatment of protoscoleces caused a signifi cant decrease in viability in a PGE-dose-dependent manner. In vivo, after treatment of cystic echinococcosis infected mice with PGE, a signifi cant decrease in nitric oxide levels (P<0.000 1) and TNF-α levels (P<0.001) was observed. This decline was strongly related to the inhibition of cyst development (rate of hydatid cyst growth inhibition=63.08%) and a decrease in CD68 expression in both the pericystic layer of hepatic hydatid cysts and liver tissue (P<0.000 1). A signifi cant diminution of iNOS, TNF-α and NF-κB expression was also observed in liver tissue of treated mice (P<0.000 1). Conclusions: Our results indicate an antihydatic scolicidal eff ect and immunomodulatory properties of PGE, suggesting its potential therapeutic role against Echinococcus granulosus infection.

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received in revised form 20 January 2016

Accepted 15 February 2016

Available online 20 March 2016

Pomegranate peel aqueous extract Tumor necrosis factor-α

iNOS

Nuclear factor-κB

1. Introduction

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a chronic zoonosis affecting humans as well as domestic animals, caused in humans by infection with the larval stage of a parasitic cestode, Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus). CE is one of the most important and widespread parasitic disease in the Mediterranean basin, especially in North Africa (Maghreb)[1]. CE is characterized by primary cyst development in the liver and lungs and other viscera of the intermediate host. E. granulosus infection is characterized by a prolonged coexistence of the parasite and the host with no eff ective rejection reaction. The variability and severity of the clinical expression of this parasitosis are associated with the duration and intensity of infection[2].

Our current experimental model of secondary echinococcosis is based on the development of hydatid cysts in the mouse peritoneal cavity after inoculation with viable protoscolices (PSCs)[3,4]. During E. granulosus infection in mice, protoscoleces diff erentiate into the metacestode 34 d post-inoculation[4]. The initial stage of experimental echinococcosis (a month) is characterized by a Th1 type immune response with an increase in interferon (IFN)-γ levels and reduced levels of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10[5]. The second phase occurs once the hydatid cyst is fully formed and is characterized by a more Th2-type response, with elevated IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10 and a decrease in IFN-γ and TNF-α[5,6]. In humans, elevated levels of nitric oxide (NO) and IFN-γ have been observedin sera from some patients with E. granulosus infections[7].

Currently, treatment modalities for CE include surgery and chemotherapy. However, surgery remains the main therapeutic approach throughout the world[8]. Therefore, it is imperative to develop alternative therapeutic approaches. Therapies using medicinal plants have emerged as potential new strategies[9-12]. Punica granatum (P. granatum) L. (common name pomegranate; subfamily Punicaceae) is a small tree originating from Asia and now widely cultivated in the Mediterranean basin, particularly in Algeria. Dried pomegranate peel is used to treat disorders such as colitis, dysentery and ulcers[13]. Pomegranate peel extract has anti-coccidial, anthelmintic and antibacterial activities[14,15]. Moreover, the root and stem barks are reported to have astringent and anthelmintic activity[13]. Several studies have demonstrated the therapeutic antioxidant, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects of P. granatum fruit, peel, and juice. These eff ects are mainly exerted by molecules like polyphenols and tannins[16-18].

In this study, we investigate the antihydatic and immunomodulatory eff ects of P. granatum peel aqueous extract (PGE) using a murine model of echinococcosis. In this context, we evaluated the eff ect of PGE on the development of murine echinococcosis and on the viability of PSCs in vitro. Furthermore, systemic levels of NO and TNF-α secretion were assessed during the experimental CE. In addition, hepatic expression of iNOS, NF-κB, TNF-α, and CD68 and histological changes were analyzed in histopathological and immune-histopathological studies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. E.granulosus protoscoleces

E.granulosus PSC was collected as described by Amri et al[19]. Briefly, the hydatid fluid was removed by aseptic puncture of fertile human pulmonary hydatid cysts. The fl uid was centrifuged at 3 000 rpm for 10 min at 4 ℃. The pellet containing PSCs was washed several times in sterile PBS supplemented with 30 μg/mL gentamicin. PSC viability was assessed prior to inoculation and determined by body movement observed under inverted microscopy and vital staining with 0.1% eosin. All samples had viability>98% at the time of experiment. Swiss mice were inoculated intraperitoneally (ip.) with 2 000 viable PSCs resuspended in 500 μL of sterile PBS[4].

2.2. Mice

Female Swiss Albino mice (four to six weeks old) were purchased from the Pasteur Institute (Algiers, Algeria). These mice were acclimated for a week before the start of experiments and kept under normal conditions with a 12 h dark/light cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Mice ranging in weight from 21 g to 23 g were divided into three groups (n=9 mice per group) as per Figure 1. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the national agency of research development in health. The control group (Ctrl) received no treatment. The CE and PGE/CE groups received intraperitoneal injection with a suspension of 2 000 viable PSCs in 500 μL of sterile PBS. The PGE/CE group was treated by daily intragastric administration of 500 μL of PGE at a concentration of 0.65 g/ kg for two months, from two days following infection. The PBS group received intraperitoneal injection with 500 μL of sterile PBS instead of PSCs. The PGE group, which was not infected with PSCs, received a daily intragastric administration of 500 μL of PGE at a concentration of 0.65 g/kg for two months. All mice were euthanized three months post-PSC inoculation.

Figure 1. Experimental plan.

2.3. Assessment of cyst development

All mice were euthanized three months post-PSC inoculation, peritoneal cysts were isolated and their weight and diameter measured. Then, the larval growth and the inhibition rate were calculated as described by Moreno et al[20].

2.4. Preparation of PGE

Pomegranate was collected during November 2012 in eastern Algeria (Beni Ourtilane). The peels were separated from fruits, dried at room temperature for 12 d, and powdered using an electric mill. The extract was prepared by aqueous maceration and fi ltered through Whatman fi lter paper.

2.5. Plasma collection

Mice were anesthetized with chloroform, and blood was collected via cardiac puncture. Blood was centrifuged to isolate plasma, which was kept at -20 ℃ until use.

2.6. Nitrite measurement

The Griess reaction was used to determine nitrite levels in plasma as an indicator of NO production, as described previously[7]. Briefl y, 100 μL of each sample was mixed with 50 μL of Griess reagent (5% sulfanilamide, 0.5% napthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride, 20% HCl). Samples were incubated at room temperature for 20 min and the absorbance read at 543 nm by spectrophotometer. The nitrite concentration was determined using a standard curve constructed with sodium nitrite [NaNO2; (0-200) μmol/mL].

2.7. Measurement of systemic TNF-α level

The systemic level of TNF-α was determined in the plasma of mice using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Camarillo, USA).

2.8. Histopathological analysis

For histological examination, small sections of liver (according to cyst localization) were excised, fi xed in 10% buff ered formalin, mounted in paraffin blocks and cut into 2-μm-thick sections. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to study histological changes, Masson’s trichrome stain to evaluate fi brosis, Perls’ stain for iron, and metachromatic toluidine blue stain for quantifi cation of cell infi ltration.

Histological criteria were based on the degree of architectural tissue changes and cellular infi ltration. Images were captured from each slide with a digital camera (Casio) on a light microscope (Motic) with 10×, 40× and 100× objectives. Morphometry was performed using FIJI image processing software after calibration with a graduated slide. The percentage of tissue fi brosis and the number of inflammatory cells in the pericystic layer of hepatic hydatid cysts were calculated using area measurement and point selection, respectively. A total of 30 photomicrographs were analyzed and quantifi ed for each liver sample.

Necroinflammatory activity was scored according to the histological activity index (HAI) described by Mekonnen et al[21]. Venous congestion was included in the HAI: 0, absence; 1, weak; 2, moderate; 3, severe. The HAI was also assigned according to the extent of fibrosis: 0, absence; 1, mild portal fibrosis; 2, moderate fibrosis; 3, severe fibrosis; and 4, cirrhosis. Steatosis was graded as follows: 0, absent; 1, 1%-10% of hepatocytes aff ected; 2, 11%-30% of hepatocytes aff ected; 3, 31%-60% of hepatocytes aff ected; and 4, >60% of hepatocytes aff ected[22]. Hepatic iron deposits were evaluated by Perls’ stain and were scored according to Brissot et al[22,23]. Histopathological diagnoses were performed in double blinded fashion by anatomopathologists (Pr. Z-CA and Mr. M-AL).

2.9. Immunohistochemical procedures

Immunohistochemical study of CD68, NF-κB, TNF-α and iNOS expression was performed on formalin-fi xed, paraffi n-embedded samples. Indirect immunoperoxidase staining was performed as described in the manufacturer’s instructions (DAKO, Denmark A/ S). Sections of 2-μm-thick tissue were deparaffi nized using xylene, and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol. The sections were then subjected to antigen retrieval in EnVision™ FLEX target retrieval solution [low pH (K8005) for iNOS, TNF-α and NF-κB detection and high pH (K8004) for CD68 detection] at 95 ℃ for 45 min. All subsequent steps were performed at room temperature in a humidifi ed chamber. Endogenous peroxide was blocked with EnVision™ FLEX peroxidase-blocking reagent (DM821) for 5 min. Monoclonal mouse anti-CD68 (clone PG-M1, DAKO, Denmark A/S) was used as primary antibody for studying the percentage of macrophages infi ltrating in pericyctic layer of hepatic hydatid cyst. We also incubated liver sections with rabbit monoclonal antibodies against mouse NF-κB/p65 subunit, TNF-α and iNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA; diluted 1:100, 1:100, and 1:500 respectively) overnight at 4 ℃. The detection of primary mouse antibodies was performed with EnVision™ FLEX. The chromagen solution 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine was added. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Slides were covered with Faramount Mounting Medium (S3025, DAKO, Denmark A/S) and color development was observed using a standard microscope (Motic). Pictures were taken using a digital camera (Casio) at 40× resolution.

The percentage of cells positively stained for iNOS, TNF-α, NF-κB and CD68 was scored semiquantitatively. The positive cells were identifi ed by brown staining (peroxidase). For NF-κB expression, we quantifi ed by determination of the intensity of the brown staining. The quantifi cation was carried out on 30 high-power fi elds in each liver sample by two observers (ML, M-AL). iNOS and TNF-αexpression was evaluated on the basis of a four-point scale: ‘−’: negative staining; ‘+’: low expression, less than 10% positive cells; ‘++’: moderate expression, 10%-50% positive cells; ‘+++’: diffuse expression, more than 50% positive cells. The intensity of NF-κB/ p65 immunostaining was evaluated as weak, moderate or intense on a subjective basis.

2.10. Protoscoleces culture

After viability assessment of PSCs, they were cultured in 48-well tissue culture plates at a density of 2 500 PSCs/mL in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine and 10% fetal calf serum, at 37 ℃ in humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. After 24 h of PSC culture, PGE or albendazole was added at 2, 4, 8 or 16 mg/ mL, or 0.02 mg/mL, respectively. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

After 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h of PSC culture, PSC viability was assayed by microscopy/eosin exclusion. The mortality rate was determined by counting a minimum of 100 PSCs (as the ratio of the number of dead PSCs/total number of PSCs). Assessment was based on PSC vital staining, motility, and morphological criteria, as described by Amri et al[19].

2.11. Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA to compare all groups. t-tests were performed to analyze both time (CE induction) and treatment eff ects. Two-way ANOVA was performed for the study of protoscolicidal activity of PGE. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for iNOS, TNF-α, NF-κB and CD68 quantification in liver sections. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for fibrosis, infiltrating cells, and CD68 quantification in the pericystic layer of hepatic hydatid cysts. Probability values of P<0.05 were considered to be statistically signifi cant.

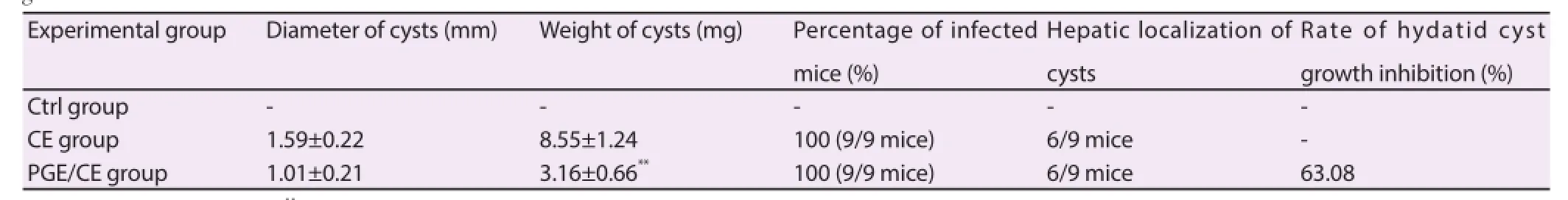

Table 1Intraperitoneal inoculation of Swiss mice with E. granulosus protoscoleces from human pulmonary hydatid cysts and study of herbal treatment with P. granatum.

3. Results

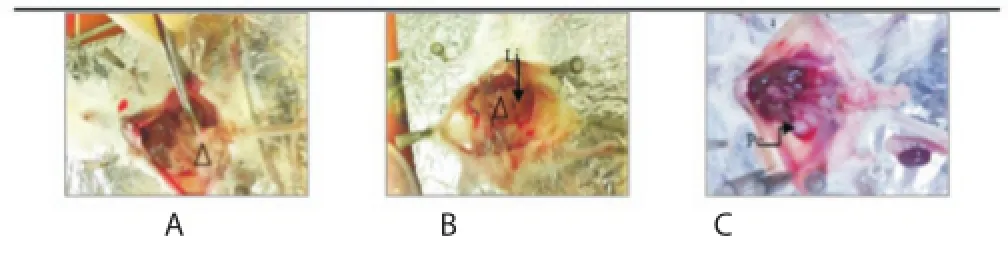

3.1. Effect of PGE on clinical parameters of secondary experimental echinococcosis

Three months post-infection, animals developed CE in the liver and other intraperitoneal areas (Figure 2) with an infectivity of 100% in both the CE group and PGE/CE group (Table 1). The diameter and the weight of developed cysts were measured to evaluate the eff ect of PGE treatment at doses of 0.65 g of the extract per kg body weight (Table 1). The diameter (P>0.05) and the weight (P<0.005) of hydatid cysts were decreased in the PGE/CE group. PGE treatment inhibited cyst growth by 63.08% in the PGE/CE group. Thus, PGE treatment induced a signifi cant reduction of the clinical symptoms during CE.

Figure 2. Intraperitoneal localization of hydatid cysts in infected mice.

3.2. PGE treatment reduced systemic levels of NO

We investigated the eff ect of PGE on NO production in secondary echinococcosis. NO measurement in plasma of mice showed a significant increase in the CE group compared to the Ctrl group [(19.17±0.58) μM vs. (2.74±0.42) μM, P<0.000 1; Figure 3A]. Administration of PGE to mice with CE caused a significant decrease in systemic NO level in comparison with the untreated-CE group (P<0.000 1; Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Oral administration of pomegranate peel aqueous extract reduced the systemic production of nitrite (A) and TNF-α (B) in vivo.

3.3. Decrease in TNF-α level in vivo

To analyze the eff ect of PGE on proinfl ammatory cytokine TNF-α production in vivo during CE development, we measured the level of TNF-α in plasma (Figure 3B). The systemic TNF-α level was decreased in the CE group in comparison with the Ctrl group (P>0.05 Figure 3B). PGE treatment attenuated TNF-α expression compared with untreated infected mice (P<0.001) and control mice (P<0.000 1).

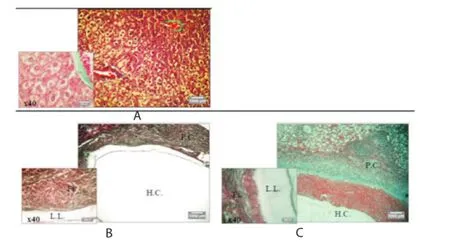

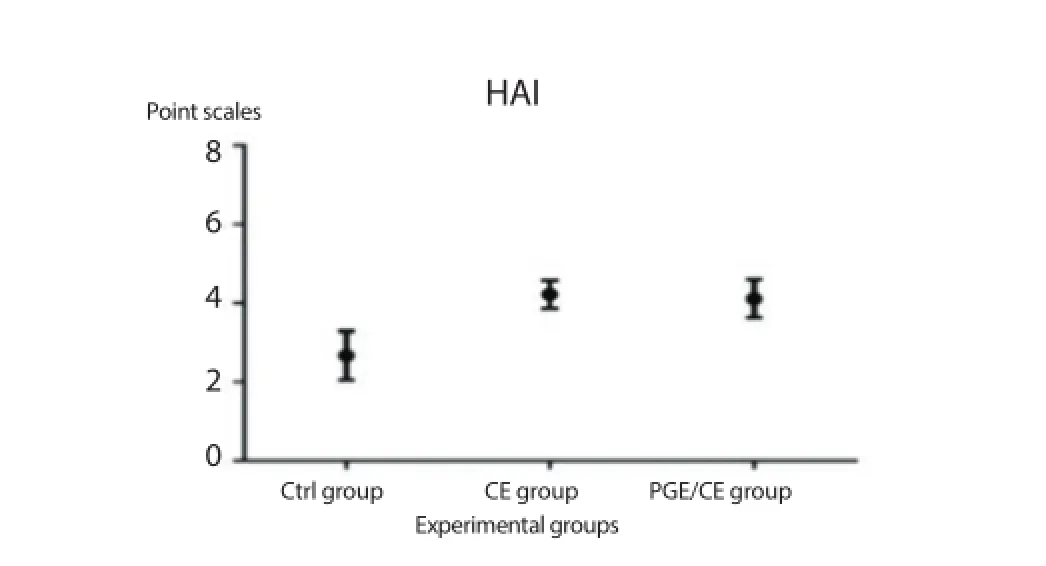

3.4. Liver architecture was improved in mice treated with PGE

Hepatic echinococcosis comprises cystic forms, associated with the establishment of a periparasitic granuloma in the liver and an irreversible fi brosis in the pericyst[24]. The fi brotic area was evaluated using Masson’s trichrome stain (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Representative photomicrographs (×10 and ×40) of Masson’s trichrome stained liver sections from the Control group (A), CE group (B), and PGE/CE group (C).

Histological analysis of liver from the CE group showing proliferation of kupff er cells, congestion of vein blood, infi ltration of infl ammation cells with portal area, degeneration of hepatocytes with fatty vacuoles (Figure 5B), associated with an intense infl ammatory cell (lymphocytes, neutrophil and macrophage) extending throughout the pericystic layer of hydatid cysts (Figure 5D). This result was correlated with what Baqer et al found[25]. This observation was accompanied by fibrosis (Figure 4B) and in some cases necrotic hepatocytes (Figure 5C). These observations contrast with the Ctrl group, which exhibited normal hepatic tissue (Figure 5A and Figure 5B).

The administration of PGE to mice with CE caused an improvement in the histological structure in liver sections relative to untreated CE mice. It was accompanied by less fi brosis (Figure 4C compared with B). Nonetheless, cellular infiltration was still observed and a homogeneous mass formed around the cyst (Figure 5E). The pericystic layer of hepatic hydatid cysts in the CE group is characterized by a more extensive fi brotic reaction than that in the pericyst of the PGE/CE group (Figure 4B compared with C). The fibrotic reaction was quantified with a significant difference between the pericyst of the CE group and of the PGE/CE group (43.75%±0.92% vs. 70.73%±1.12%, P<0.000 1).

Figure 5. Representative photomicrographs (×10 and ×40) of H&E stained liver tissue from Control group, CE group, and PGE/CE group.

The oral administration of PGE to Swiss mice did not cause any toxic or secondary eff ects. No toxic eff ects were observed in the PGE/CE group, which was confi rmed via histopathological analysis of mouse liver (Figure 5F). A decrease in the histology damage score (HAI) was shown in the PGE/CE group compared with the CE group (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Improvement of the histological structure by administration of PGE in mice infected with PSCs.

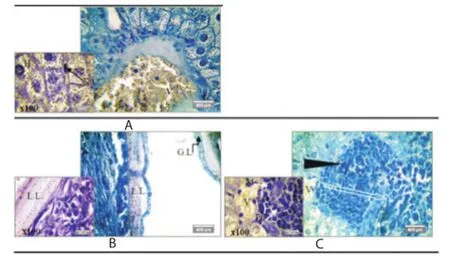

Toluidine blue staining was applied for identification of cells infiltrate (macrophages and plasma cells) in pericystic layer of hydatid cyst. An intense immune response against hydatid cyst development was involved in pericystic layer of CE group by severe cells infi ltrate (macrophages, lymphocytes and polynuclear cells) with a significant difference compared with PGE/CE group [(36.38±1.32) cells infiltrating/mm2 vs. (47.05±1.70) cells infi ltrating/mm2, P<0.000 1; Figure 7B].

Figure 7. Representative photomicrographs (×40, ×100) of toluidine blue stained liver sections with Lison’s method from the Control group (A), CE group (B), and PGE/CE group (C).

Histopathological analysis of hepatic hydatid cysts from the PGE/CE group demonstrated a moderate immune response to the infection, characterized by a fi brotic reaction and infl ammatory cells. Interestingly, this observation correlated with a signifi cant decrease in the growth of cysts in the liver.

3.5. Down regulation of iNOS, TNF-α and NF-κB expression in liver sections of the PGE/CE group

The expression of iNOS, TNF-α and NF-κB was shown in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (Figure 8). The expression wassignifi cantly increased in the CE group compared with the untreated Ctrl group (P<0.000 1; Table 2). This increase in expression in liver sections was signifi cantly attenuated by PGE treatment (P<0.000 1; Table 2). In liver biopsies of the PGE/CE group and Ctrl group, there was, strikingly, no signifi cant diff erence in NF-κB expression.

Figure 8. Representative images (×40) of immunohistochemical analysis for iNOS, TNF-α and NF-κB expression in liver with hepatic hydatid cysts.

Table 2Percentages of iNOS, TNF-α, NF-κB, and CD68 expression in hepatic sections of Ctrl group, CE group, and PGE/CE group.

Table 3Eff ect of P. granatum on protoscolex viability.

3.6. Decrease of CD68 expression in liver sections of the PGE/ CE group

Interest a positive reaction was observed for CD68 in infected mice (Figure 9 and Table 2). A signifi cant decrease in cells that express CD68 (Kupff er cells) in the liver sections of mice treated with PGE was clearly demonstrated in comparison with the CE group (CD68: 1.56%±0.06% vs. 4.60%±0.21%, P<0.000 1). A similar result was also observed in the pericystic layer of hepatic hydatid cysts of the PGE/CE group in comparison with the CE group for CD68 macrophage infi ltrating cells (0.30%±0.02% vs. 0.96%±0.08%, P< 0.000 1). The fi brotic tissue revealed the presence of macrophages (CD68 positive), although other infl ammatory cells were also present in both infected and treated mice.

Brown-staining indicates specific CD68 detection in all hepatic sections. Pericystic sections of infected mice show the CD68 expression was enhanced in comparison with the non-cystic liver sections (Figure 9 and Table 2).

Figure 9. Immunohistochemical analysis of liver biopsies associated with cystic localization in representative images (×40) for marker CD68.

3.7. In vitro scolicidal activity of PGE

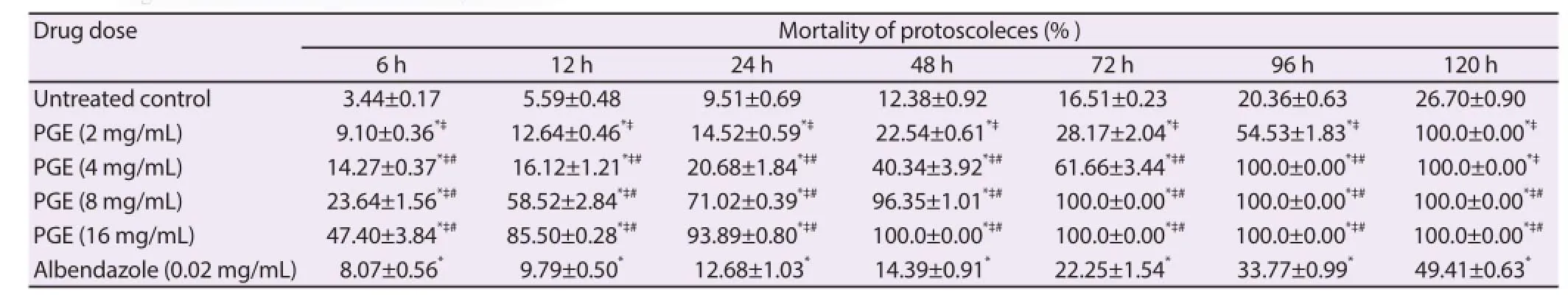

In this study, the anthelmintic eff ect of PGE was demonstrated in vitro in culture of protoscoleces from human pulmonary hydatid cysts. The viability of PSCs was assessed by the 0.1% aqueous eosin red stain method (Figure 10). The mortality of PSCs after exposure to different concentrations of PGE for various time periods is reported in Table 3. PSCs were treated with 2, 4, 8 or 16 mg/mL PGE or 0.02 mg/mL albendazole after 24 h of culture. Albendazole has been shown to have potent scolicidal eff ects against protoscoleces of hydatid cysts[26]. Thus, protoscoleces were treated with 0.02 mg/mL of albendazole as positive control. The mortality of PSCs was determined at 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h posttreatment. Drug was added 24 h after culture of viable protoscoleces at a density of 2 500 PSCs/mL.

The scolicidal activity of PGE was observed from 6 h post-treatment at the lowest concentration (2 mg/mL). In fact, the mortality of PSCs at this time point and at the lowest PGE concentration was higher than on albendazole treatment (9.10%±0.36% vs. 8.07%±0.56%).

PSC treatment with PGE induced a signifi cantly higher mortality that increased with dose and treatment period, reaching 100% when PGE was given at 16 mg/mL for only 2 d. The effi cacy at the lowest dose from 48 h post-treatment was better than that of albendazole administered alone (22.54%±0.61% vs. 14.39%±0.91%; Figure 10). However, after a longer period (5 d), untreated PSCs showed mortality (20.36%±0.63%). Our results indicate that the scolicidal activity of PGE is both dose- and time-dependent.

Figure 10. Morphological aspects of cultured PSCs in the presence of PGE or albendazole (×40).

4. Discussion

The liver is the major site of hydatid disease. The goals of hepatic hydatid cyst treatment are a complete elimination of metacestodes and prevention of recurrence, minimizing mortality and morbidity risk. In order to achieve these aims, it is essential to choose the most appropriate treatment to the clinical aspect of cysts[27]. Currently, the basic approaches for treatment of hydatid cyst are surgery and chemotherapy[8,27]. However, operative leakage may lead to dissemination of viable protoscolices to adjacent tissues and thus to develop secondary infection[28]. Furthermore, antiparasitic drugs treatments such as benzimidazole analogs are potentially toxic in many subjects[29]. In this regard, our investigations based on the use of a medicinal plant (P. granatum) were conducted to evaluate both an alternative natural drug with no toxic eff ects and its protective abilities.

Studies of pomegranate constituents on animals at concentrations and levels commonly used in folk and traditional medicines note no toxic eff ects. P. granatum peel extract is a rich source of phytochemicals that can produce toxic eff ects at higher consumption rates or from long-term administration[30]. Patel et al[31] reported that the oral lethal dose 50 of PGE in Wistar rats and Swiss albino mice was>5 g/kg body weight. In our study, the oral lethal dose 50 of PGE in Swiss mice (n=10) was (6.53±0.12) g/kg. Repeated oral administration to Swiss mice during two months of treatment once a day at doses of 0.65 g/kg body weight produced no toxic eff ects in terms of food intake, weight gain, behavioral parameters, or histopathological results.

Intragastric administration of PGE in Swiss mice showed a signifi cant inhibitory eff ect on hydatid cyst development. Actually, our data showed a decrease in hydatid cyst weight and diameter in PGE/CE group. Those observations correlate with a less fibrotic reaction in the pericystic layer of hepatic hydatid cysts. Histological study of liver confi rmed irreversible fi brosis on CE infection. In fact, the percentage of fibrosis was significantly lower in the PGE/CE group than in the CE group.

The antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective eff ect of pomegranate peel and vinegar was evaluated in Wistar rats by Ashoush et al[32] and Bouazza et al[33] using various biochemical parameters and histopathological studies. Other studies have shown a hepatoprotective capacity of pomegranate peel extract against t-BOOH and CCI4, cytotoxic agents studied as liver toxicants[34,35]. These eff ects might be correlated with a radical scavenging eff ect[35]. Based on the results of our histopathological study and on NO measurement in plasma, PGE exhibited a potential antioxidant eff ect. The literature indicates that the antioxidant eff ect of pomegranate may be related to its phenolic content, which is higher in peels and fl owers than in leaves and seeds[36].

Many studies have investigated the antioxidant and antiinfl ammatory eff ects of pomegranate peel in vivo and in vitro. Hou et al[37] showed the inhibition of NO production by procanthocyadins and anthocyanidins, compounds of pomegranate peel and juice. Ellagitannins (punicalin and punicalagin) extracted from pomegranate peel have antioxidant activities and downregulate UV-B mediated activation of NF-κB[38]. In addition, Rosillo et al[39] demonstrated that ellagic acid-enriched pomegranate extract attenuates chronic colonic infl ammation in rats by both reduction of pro-inflammatory TNF-α production and inhibition of proinfl ammatory cyclo-oxygenase-2 and iNOS protein expression in colon tissue from TNBS-induced colitis rats.

In our study, the immunochemical marker CD68 was used for assessment of the infl ammatory reaction in the pericystic layer of hepatic hydatid cysts and the non-cystic liver sections (macrophageinfi ltrate and kupff er cells detection, respectivelly). CD68 expression in the CE group was higher in the pericystic layer of hepatic hydatid cysts compared with liver tissue sections. In the PGE/ CE group, we showed a significant decrease of CD68 expression in the liver sections and in the pericystic layer of hepatic hydatid cysts. Using CD68 detection, we identified the involvement of macrophages against CE. We observed with interest that PGE administration reduced both the levels of CD68 Kupff er cells and CD68 macrophages in liver tissues and in pericytic areas. The antiinfl ammatory and hepatoprotective eff ects of pomegranate was also demonstrated by a localized attenuation of NF-κB, iNOS, TNF-αexpression and systemic decrease in NO and TNFα levels in PGE/ CE group. Concomitantly, PGE treatment caused an important decrease of HAI score and infl ammatory cells infi ltration.

Many studies reported that NO produced by the monocyte/ macrophage system has toxic activities against E. granulosus infection[7,40]. These toxic effects induced by NO on hepatic hydatid cysts were previously investigated by Ait Aissa et al[40]. In our current study, we focused our attention on the eff ect of PGE treatment on NO production and TNF-α secretion knowing that this cytokine is a hallmark of infl ammatory response and is involved in the expression of inducible NO synthase. In fact, massive NO production is a result of iNOS induction in response to lipopolysaccharides and proinfl ammatory cytokines, including TNF-α[41]. Many authors have reported the effect of TNF-α on iNOS expression through NF-κB activation[42]. In our work, we report the presence of inducible NO synthase in liver biopsies of the CE and PGE/CE groups by an immunohistochemical method using monoclonal antibodies against mouse iNOS. The cytoplasmic expression of iNOS was related to the presence of NF-κB and TNF-α in hepatocytes of hepatic hydatid cysts and also in Kupff er cells. Remarkably, we noticed a signifi cant decrease of iNOS, NF-κB and TNF-α expression after treatment with PGE. The anti-infl ammatory properties of PGE are marked by a systemic decrease in NO level and TNF-α level in the PGE/CE group in comparison with the CE group. These results are associated with the reduction of CE development.

Moreover, the scolicidal eff ect of PGE in various concentrations and over diff erent time periods was reported here. In our study, the viability of PSCs was aff ected following the addition of ascending concentrations of PGE (2, 4, 8, 16 mg/mL). The death rate of protoscoleces reached 100% at the lowest concentration after 120 h. It is notable that increasing exposure time resulted in greater protoscolicidal activity. It has been suggested that the dose-dependent protoscolicidal eff ects of medicinal plant extracts such as Nigella Sativa are due to their ability to inhibit DNA synthesis by inhibiting histone deacetylase enzyme interacting with the chromosomes or in breaking down biological activities of protoscoleces through interference with metabolism[43]. The extracts may have target sites such as inhibitors of protein or DNA synthesis[44]. Moreover, most of the antimicrobial activity in medicinal plants appears to be derived from phenolic compounds[10]. The exact mechanism of the antiparasitic eff ect of PGE is not clear and further studies must be conducted to identify the bioactive compounds of pomegranate and to elucidate their mechanisms against cystic echinococcosis. Thus, according to these data, we can conclude that the PGE could be considered as a safe and potent scolicidal agent.

In conclusion, our data support the hypothesis that PGE treatment has both anthelminthic and immunomodulatory eff ects against the development of experimental echinococcosis. PGE administration effectively promoted an antihydatic effect and improved antiinfl ammatory and protective responses. Our results suggest that PGE aff ords therapeutic advantages and may be a good candidate in the treatment of human hydatidosis.

Conflict of interest statement

The author reports no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Pr. Zine-Charaf Amir for his important contribution in histological study, Mohamed-Amine Lazourgui for his important contribution in histological and immunohistological study and for his technical help.

References

[1] Dakkak A. Echinococcosis/hydatidosis: A severe threat in Mediterranean countries. Vet Parasitol 2010; 174(1-2): 2-11.

[2] Mezioug D, Touil-Boukoffa C. Interleukin-17A correlates with interleukin-6 production in human cystic echinococcosis: a possible involvement of IL-17A in immunoprotection against Echinococcus granulosus infection. Eur Cytokine Netw 2012; 23(3): 112-119.

[3] Dematteis S, Rottenberg M, Baz A. Cytokine response and outcome of infection depends on the infective dose of parasites in experimental infection by Echinococcus granulosus. Parasite Immunol 2003; 25(4): 189-197.

[4] Urrea-Paris MA, Moreno MJ, Casado N, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F. Relationship between the effi cacy of praziquantel treatment and the cystic diff erentiation in vivo of Echinococcus granulosus metacestode. Parasitol Res 2002; 88(1): 26-31.

[5] Rogan MT. T-cell activity associated with secondary infections and implant cysts of Echinococcus granulosus in BALB/c mice. Parasite Immunol 1998; 20(11): 527-533.

[6] Haralabidis S, Karagouni E, Frydas S, Dotsika E. Immunoglobulin and cytokine profi le in murine secondary hydatidosis. Parasite Immunol 1995; 17(12): 625-630.

[7] Touil-Boukoffa C, Bauvois B, Sanceau J, Hamrioui B, Weitzerbin J. Production of nitric oxide (NO) in human hydatidosis: relationship between nitrite production and interferon-gamma levels. Biochemie 1998; 80(8-9): 738-744.

[8] Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Tropica 2010; 114(1): 1-16.

[9] Pensel PE, Maggiore MA, Gende LB, Eguaras MJ, Denegri MG, Elissondo MC. Effi cacy of essential oils of Thymus vulgaris and Origanum vulgare on Echinococcus granulosus. Interdiscip Persp Infect Dis 2014: 693289. Doi: 10.1155/2014/693289.

[10] Moazeni M, Roozitalab A. High scolicidal eff ect of Zataria multiflora onprotoccoleces of hydatid cyst: an in vitro study. Comp Clin Pathol 2012; 21(1): 99-104.

[11] Zibaei M, Sarlak A, Delfan B, Ezatpour B, Azargoon A. Scolicidal eff ects of Olea europaea and Satureja khuzestanica extracts on protoscolices of hydatid cysts. Korean J Parasitol 2012; 50(1): 53-56.

[12] Yones DA, Taher GA, Ibraheim ZZ. In vitro eff ects of some herbs used in Egyptian traditional medicine on viability of protoscolices of hydatid cysts. Korean J Parasitol 2011; 49(3): 255-263.

[13] Braga LC, Shupp JW, Cumings C, Jett M, Takahashi JA, Carmo I, et al. Pomegranate extract inhibits Staphylococcus aureus growth and subsequent enterotoxin production. J Ethnopharmacol 2005; 96(1-2): 335-339.

[14] Dkhil MA. Anti-coccidial, anthelmintic and antioxidant activities of pomegranate (Punica granatum) peel extract. Parasitol Res 2013; 112(7): 2639-2646.

[15] Khan AJ, Hanee S. Antibacterial properties of Punica granatum peels. Int J Appl Biol Pharm Technol 2011; 2(3): 23-27.

[16] Kadi H, Moussaoui A, Benmehdi H, Lazouni HA, Benayahia A, Nahal bouderba N. Antibacterial activity of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Punica granatum L. bark. J Appl Pharmaceut Sci 2011; 01(10): 180-182.

[17] Cerda B, Llorach R, Ceron J, Espin JC, Tomas-Barberan FA. Evaluation of the bioavailability and metabolism in the rat of punicalagin, an antioxidant polyphenol from pomegranate juice. Eur J Nutr 2003; 42(1): 18-28.

[18] Gracious RR, Selvasubramanian S, Jayasundar S. Immunomodulatory activity of Punica granatum in rabbits-a preliminary study. J Ethnopharmacol 2001; 78(1): 85-87.

[19] Amri M, Ait Aissa S, Belguendouz H, Mezioug D, Touil-Boukoffa C. In vitro antihydatic action of IFN-γ is dependent on the nitric oxide pathway. J Interf cytok Res 2007; 27(9): 781-787.

[20] Moreno MJ, Urrea-Paris MA, Casado N, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F. Praziquantel and albendazole in the combined treatment of experimental hydatid disease. Parasitol Res 2001; 87(3): 235-238.

[21] Adinolfi LE, Utili R, Andreana A, Tripodi M-F, Marracino M, Gambardella M, et al. Serum HCV RNA levels correlate with histological liver damage and concur with steatosis in progression of chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci 2001; 46(8): 1677-1683.

[22] Mekonnen GA, Ijzer J, Nederbragt H. Tenascin-C in chronic canine hepatitis: Immunohistochemical localization and correlation with necroinfl ammatory activity, fi brotic stage, and expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin, cytokeratin 7, and CD3+cells. Vet Pathol 2007; 44(6): 803-813.

[23] Brissot P, Bourel M, Herry D, Verger JP, Messner M, Beau-mont C, et al. Assessment of liver iron content in 271 patients: A re-evaluation of direct and indirect methods. Gastroenterol 1981; 80(3): 557-565.

[24] Beschin A, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA. Contribution of myeloid cell subsets to liver fi brosis in parasite infection. J Pathol 2013; 229(2): 186-197.

[25] Baqer NN, Khuder MH, Amer N. Antiprotoscolices eff ects of ethanolic extract of Zingiber officinale against Echinococcus granulosus in vitro and in vivo. Int J Adv Res 2014; 2(10): 59-68.

[26] Paksoy Y, Odev K, Sahin M, Arslan A, Koç O. Percutaneous treatment of hydatid cysts: comparison of direct injection of albendazole and hypertonic saline solution. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 185(3): 727-734.

[27] Nunnari G, Pinzone MR, Gruttadauria S, Celesia MB, Madeddu G, Malaguarbera G, et al. Hepatic echinococcosis: clinical and therapeutic aspects. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(13): 1448-1458.

[28] Moazeni M, Nacer A. In vitro effectiveness of garlic (Allium sativum) extract on scolices of hydatid cyst. World J Surg 2010; 34(11): 2677-2681.

[29] Whittaker SG, Faustman EM. Effects of benzimidazole analogs on cultures of diff erentiating rodent embryonic cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1992; 113(1): 144-151.

[30] Vidal A, Fallarero A, Pena BR, Medina ME, Gra B, Rivera F, et al. Studies on the toxicity of Punica granatum L. (Punicaceae) whole fruit extracts. J Ethnopharmacol 2003; 89(2-3): 295-300.

[31] Patel C, Dadhaniya P, Hingorani L, Soni MG. Safety assessment of pomegranate fruit extract: acute and subchronic toxicity studies. Food Chem Toxicol 2008; 46(8): 2728-2735.

[32] Ashoush IS, El-Batawy OI, El-Shourbagy GA. Antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective eff ect of pomegranate peel and whey powders in rats. Ann Agr Sci 2012; 58(1): 27-32.

[33] Bouazza A, Bitam A, Amiali M, Bounihi A, Yargui L, Koceir EA. Effect of fruit vinegars on liver damage and oxidative stress in high-fat-fed rats. Pharm Biol 2015; 8: 1-6.

[34] Hiraganahalli BD, Chinampuder VC, Dethe S, Mundkinaieddu D, Pandre MK, Blachandran J, et al. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant activity of standardized herbal extracts. Pharmacogn Mag 2012; 8(30): 116-123.

[35] Murthy KNC, Jayaprakasha GK, Singh RP. Studies on antioxidant activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum) peel extract using in vivo models. J Agric Food Chem 2002; 50(17): 4791-4795.

[36] Elfalleh W, Hannachi H, Tlili N, Yahia Y, Nasri N, Ferchichi A. Total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities of pomegranate peel, seed, leaf and fl ower. J Med Plants Res 2012; 6(32): 4724-4730.

[37] Hou DX, Ose T, Lin S, Harazoro K, Imamura I, Kubo M, et al. Anthocyanidins induce apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia cells: structure-activity relationship and mechanisms involved. Int J Oncol 2003; 23(3): 705-712.

[38] Afaq F, Malik A, Syed D, Maes D, Matsui MS, Mukhtar H. Pomegranate fruit extract modulates UV-B-mediated phosphorylation of mitogenactivated protein kinases and activation of nuclear factor kappa B in normal human epidermal keratinocytes paragraph sign. Photochem Photobiol 2005; 81(1): 38-45.

[39] Rosillo MA, Sánchez-Hidalgo M, Cárdeno A, Aparicio-Soto M, Sánchez-Fidalgo S, Villegas I, et al. Dietary supplementation of an ellagic acidenriched pomegranate extract attenuates chronic colonic infl ammation in rats. Pharmacol Res 2012; 66(3): 235- 242.

[40] Ait Aissa S, Amri M, Bouteldja R, Weitzerbin J, Touil-Boukoffa C. Alterations in interferon-gamma and nitric oxide levels in humain echinococcosis. Cell Mol Biol 2006; 52(1): 65-70.

[41] Bogdan C. Nitric oxide and the immune response. Nat Immunol 2001; 2(10): 907-916.

[42] Cheshire JL, Baldwin AS. Synergistic activation of NF-kappa B by tumor necrosis factor alpha and gamma interferon via enhanced kappa B alpha degradation and de novo Ⅰ kappa B beta degradation. Mol Cell Biol 1997; 17(11): 6746-6754.

[43] Mahmoudvand H, Asadi A, Harandi MF, Sharififar F, Jahanbakhsh S, Dezaki ES. In vitro lethal eff ects of various extracts of Nigella sativa seed on hydatid cyst protoscoleces. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2014; 1(4): 1-6.

[44] Yones DA, Taher GA, Ibraheim ZZ. In vitro eff ects of some herbs used in Egyptian traditional medicine on viability of protoscolices of hydatid cysts. Korean J Parasitol 2011; 49(3): 255-263.

Document heading 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.01.038

IF: 1.062

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine

journal homepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/apjtm

15 December 2015

*Corresponding author: Chafia Touil-Boukoffa, Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Department of Biology, University of Sciences and Technology Houari Boumediene, Algiers, Algeria.

E-mail: touilboukoff a@yahoo.fr

Tel: +213 550819857

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Preinduced intestinal HSP70 improves visceral hypersensitivity and abnormal intestinal motility in PI-IBS mouse model

- Mechanism of all-transretinoic acid increasing retinoblastoma sensitivity to vincristine

- Protective effect of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase1 inhibitor against mice liver injury

- Effect of TRPV1 combined with lidocaine on cell state and apoptosis of U87-MG glioma cell lines

- Effect of miR-467b on atherosclerosis of rats

- Effect of dimethyl fumarate on rats with chronic pancreatitis