环境内分泌干扰化合物干扰胰岛素分泌潜在作用机理

2014-09-21韩绍伦李剑王子健

韩绍伦,李剑,*,王子健

1. 北京师范大学水科学研究院 地下水污染控制与修复教育部工程研究中心,北京 100875 2. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心,北京 100085

环境内分泌干扰化合物干扰胰岛素分泌潜在作用机理

韩绍伦1,李剑1,*,王子健2

1. 北京师范大学水科学研究院 地下水污染控制与修复教育部工程研究中心,北京 100875 2. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心,北京 100085

不断升高的糖尿病发病率在全球范围内引起广泛关注,流行病学调查显示糖尿病发病率的增加与环境内分泌干扰化合物使用量增大之间存在显著相关,环境内分泌干扰化合物可能增加糖尿病发病风险,是影响糖尿病的危险因素。在此背景下,综述了环境内分泌干扰化合物暴露与糖尿病发病之间的流行病学关系;环境内分泌干扰化合物暴露对胰岛β细胞胰岛素分泌的调节、高胰岛素效应及其潜在的作用机理,表明影响胰岛素分泌是环境内分泌干扰化合物调节代谢,诱发糖尿病的重要作用机制。

环境内分泌干扰物;作用机理;糖尿病;胰岛素;雌激素受体

环境内分泌干扰化合物(EDCs)是指干扰体内内稳态调节、繁殖、发育行为以及相关激素的合成、分泌、转运、结合、作用或消除的外源因子(美国国家环境保护局,USEPA)[1]。环境内分泌干扰物又称为环境激素,按其来源可分为天然和人工合成化合物两大类[2]。天然激素是指人体或生物体正常分泌的激素类物质;人工合成的内分泌干扰物包括人工合成的类激素化合物以及人工合成的其他化合物如多氯联苯(PCBs)、全氟化合物(PFCs)、溴代阻燃剂(BFRs)等。研究证实,EDCs能够干扰生物体内分泌系统,对生物个体及其后代造成危害[3]。然而,最新的研究表明,EDCs还可能与糖尿病的发生相关[4]。

糖尿病是一种典型的内分泌代谢疾病,近年来,全球糖尿病发病率显著增加,糖尿病已经成为继肿瘤、心血管疾病后的第三大严重威胁人类健康的慢性疾病。我国是世界第一糖尿病大国,发病率为9.6%,高于世界平均水平,95%的患病人群为2型糖尿病[5],其主要特征为胰岛素抵抗和胰腺β细胞功能下降或数量减少导致的胰岛素分泌相对不足[6]。现代医学认为基因易感性、生活方式改变、老龄化和社会经济因素等是2型糖尿病发病的可能原因[6-7]。但是,流行病学调查发现,过去40年间,2型糖尿病发病率的增加与EDCs使用量增大之间存在显著相关,因此提出EDCs可能增加2型糖尿病发病风险,是影响糖尿病的危险因素[8-10]。

1 环境内分泌干扰化合物暴露与糖尿病发病之间的相关性

基于流行病学调查建立EDCs暴露,如PCBs、PFCs、BFRs、二恶英、有机氯农药(OCPs)、双酚A(BPA)、邻苯二甲酸酯(PAEs)等,与2型糖尿病发生之间的相关性[11-17]。例如,Lee等[16]检测了2 016名成年志愿者血清中PCBs等6种化合物的浓度,发现血清PCBs浓度与2型糖尿病之间存在显著相关。Lin等[13]系统分析了血清PFCs浓度与体内葡萄糖代谢平衡之间的相关性,证实成人PFCs暴露浓度与胰岛素抵抗呈正相关。在美国开展的健康和营养调查(National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHANES)结果表明,成年男性血清中6种BFRs含量与糖尿病以及代谢综合征相关,并且其剂量-效应关系呈倒U型[14]。Uemura等[18]在2002—2006年期间,采用调查问卷以及空腹采血分析的方式,检测1 374名志愿者血液中10种多氯二苯并二恶英(PCDDs)和7种多氯二苯并呋喃(PCDFs),证实二恶英与糖尿病、心脑血管疾病以及代谢综合征相关。Park等[15]利用高效气相色谱-高分辨质谱法(GC-HRMS)检测社区健康调查志愿者血清中包括β-六六六(β-HCH)和七氯环氧化物在内的8种OCPs,调查分析结果表明OCPs与代谢综合征及胰岛素抵抗之间存在显著相关。Lang等[19]分析美国1455名志愿者尿液中BPA浓度,结果表明尿液BPA浓度与糖尿病发病之间显著相关。Richard等[20]利用对数转换稳态模型(HOMA)评估PAEs暴露与胰岛素抵抗之间的相关性,测试结果表明不同年龄、种族、职业成年男性尿液中6种PAEs代谢物浓度与HOMA方法计算得到的胰岛素抵抗之间呈正相关,证实环境PAEs暴露可能导致2型糖尿病发生。

除了流行病学调查,动物实验的证据也证实EDCs暴露与糖尿病发病之间存在相关。Hoppe和Carey[21]采用14 mg·kg-1多溴联苯醚(PBDE)对大鼠进行染毒,测试表明染毒后胰岛素刺激下的葡萄糖代谢能力显著降低,表现出糖尿病症状。Alonso-Magdalena等[22]的研究表明,以10、100 μg·kg-1·d-1BPA和17β-雌二醇(E2)分别对小鼠进行染毒,可导致小鼠出现胰岛素抵抗,增加罹患糖尿病的风险;Batista等[23]采用100 μg·kg-1·d-1BPA对小鼠短期染毒8 d,发现小鼠机体能量代谢减慢,可能诱发胰岛素抵抗甚至2型糖尿病。Kamath和Rajini[24]以20和40 mg·kg-1·d-1的农药乐果对小鼠染毒1个月后,发现小鼠产生胰岛素抵抗并伴有胰腺损伤,出现糖尿病症状。

糖尿病的致病机理非常复杂,虽然流行病学和动物实验证据均证实EDCs的暴露与糖尿病发生之间存在相关性,但其病理机制并不明确。现有的研究提出,EDCs可通过影响胰岛素分泌、引发胰岛素抵抗或其他的间接机制(如作用内分泌系统、作用神经系统等)诱发糖尿病[25-27]。其中,影响胰岛素分泌是EDCs调节代谢,诱发糖尿病的重要作用机制[28],这主要是由于胰岛素是体内唯一能够降低血糖水平的激素,对维持体内血糖平衡起着至关重要的作用,胰岛素分泌异常可显著增加糖尿病风险[20]。

2 环境内分泌干扰化合物暴露影响胰岛β细胞分泌胰岛素

生物体内的胰岛素主要由胰岛分泌,每个胰岛包括5种约1 000~3 000个胰岛细胞,其中数量最多的是具有胰岛素合成和分泌功能的胰岛β细胞;其次是合成和分泌胰高血糖素的胰岛α细胞;另外,胰岛中还存在比例相对较低的δ细胞和PP细胞,这2类细胞分别分泌释放生长激素抑制激素和胰多肽;此外,还存在一种比例更低的ε细胞,在胰岛中的主要作用是分泌生长激素释放激素[29]。胰岛β细胞对血液中营养物质,特别是葡萄糖浓度的变化敏感,当血糖浓度增加时,β细胞分泌释放出胰岛素,促进外围周边组织(肝、肌肉和脂肪组织)摄取葡萄糖合成并存储为糖原或甘油三酯,以降低血液中葡萄糖浓度[30]。

目前的研究证实EDCs可作用于β细胞,干扰胰岛素分泌[31],胰岛β细胞已成为EDCs毒作用的重要靶位点。例如天然雌激素和人工合成的雌激素化合物已被证实可作用于胰岛β细胞,调节胰岛素分泌[31]。生理浓度的天然雌激素(E2)对β细胞具有保护作用,可促进胰岛素分泌,具体表现为,生理浓度的E2能够减少β细胞凋亡,维持细胞胰岛素分泌功能[32]。细胞的增生与凋亡对于维持β细胞数目稳定和功能非常重要,Contreras等[33]通过离体试验证实E2能够减少人胰岛β细胞凋亡。May等[34]采用小鼠活体试验进一步证实,E2能够拮抗链佐霉素(STZ)诱导的β细胞氧化应激反应,减少细胞凋亡,保护细胞功能。除此之外,E2还能够促进β细胞胰岛素合成与分泌。Alonso-Magdalena等[26]报道E2能够调节成年大鼠β细胞胰岛素分泌,E2暴露与胰岛素分泌之间呈现显著的剂量-效应关系。E2还能够增加胰岛素的合成,E2暴露组中β细胞内胰岛素mRNA水平显著高于对照组,证实E2能够增加胰岛素基因表达[35]。

一些人工合成的雌激素化合物,如BPA、己烯雌酚(DES)、PAEs、烷基酚等能够模拟雌激素作用于β细胞,调节胰岛素分泌[28,31]。Batista等[23]报道低浓度BPA(100 mg·kg-1BPA)暴露可促进成年大鼠胰岛素分泌并导致胰岛素抵抗;BPA直接作用于β细胞,增加胰岛素分泌,具有“高胰岛素效应(insulinotropic action)”。Song等[36]也报道了类似结果,佐证了低浓度BPA的高胰岛素效应。Soriano 等[37]比较低浓度BPA(环境相关剂量,1 nmol·L-1)对小鼠和人β细胞胰岛素分泌的调节作用,证实相同剂量下,BPA对人β细胞的高胰岛效应强于小鼠。Newbold等[38]报道DES,一种人工合成的雌激素化合物,染毒小鼠后,血清胰岛素水平显著提高,证实DES具有高胰岛素效应。Song等[36]采用离体试验构建了DES促进小鼠β细胞胰岛素分泌的剂量-效应关系。一些烷基酚化合物,如辛基酚(OP)和壬基酚(NP),低浓度(2.5 μg·L-1)下表现为促进胰岛素分泌,高浓度(250 mg·L-1)下表现为抑制胰岛素分泌,呈现显著的倒U型剂量-效应关系[36]。一些PAEs,如邻苯二甲酸二丁酯(DBP)、邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基己基)酯(DEHP)和邻苯二甲酸苯基丁酯(BBP),也被报道具有胰岛素分泌干扰活性,但报道结果并不一致。Lin等[39]采用DEHP(1.25和6.25 mg·kg-1·d-1)染毒怀孕Wistar鼠,在孕期和哺乳期持续染毒,导致子代雄鼠血清胰岛素水平显著增加。但Gayathri等[40]则报道低浓度DEHP染毒小鼠导致血清胰岛素水平显著降低,停止染毒后胰岛素水平恢复正常。该差异的产生可能与测试方法不同相关,例如模型动物不同,暴露时间不同,测试终点不同,化合物暴露浓度存在差异等。

除上述之外,一些其他的EDCs化合物也参与调节β细胞胰岛素分泌。Novelli等[41]报道二恶英(TCDD)染毒离体小鼠胰岛后,能够显著影响胰岛分泌的胰岛素含量,与对照组相比,胰岛素分泌量减少。Piaggi等[42]的研究进一步佐证TCDD染毒胰岛细胞INS-1E后,显著降低细胞成活率,导致大量细胞凋亡,具有分泌活性的细胞数量减少。有机磷农药(OPs)也可参与胰岛素分泌调节,Ghafour-Rashidi等[43]将小鼠暴露于不同浓度(15、30、60 mg·kg-1)有机磷农药二嗪农以及茶碱和西地那非中,研究证实上述3种化学物质能够调节小鼠胰岛素分泌量,显著减少小鼠体内胰岛素含量。Pournourmohammadi等[44]的研究也证实另一有机磷农药,马拉松(Malathion)暴露活体小鼠后,能够在一定程度上改变胰岛分泌细胞形态,调节胰岛素的分泌,在高糖或低糖与氯化钾共同作用下,能够降低胰岛素的分泌量。

EDCs对β细胞的高胰岛效应可过度刺激胰岛素信号途径,导致β细胞损伤和胰岛素抵抗,诱导2型糖尿病的发生[45]。以研究较多的BPA为例,研究发现BPA浓度为10-12~10-10mol·L-1时即可对胰岛素分泌产生显著影响,而该浓度水平与文献报道人体BPA的暴露浓度水平相当,表明环境BPA的暴露可能已经影响到体内胰岛素的分泌,而胰岛素的过度分泌可能导致代谢紊乱,引起胰岛素抵抗,增加糖尿病风险[46]。由此可见,EDCs通过对胰岛素分泌的调节、对代谢系统的干扰,已成为一类影响人类健康的重要风险物质。

3 环境雌激素化合物干扰胰岛素分泌潜在作用机理

经典的葡萄糖刺激β细胞胰岛素分泌的过程(glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, GSIS)可简单描述为:葡萄糖通过葡萄糖转运体2(GlUT2)进入胰岛β细胞,胞内葡萄糖代谢使得三磷酸腺苷/二磷酸腺苷(ATP/ADP)比值增大,ATP敏感的KATP+通道关闭,细胞去极化,导致电压依赖性的Ca2+通道打开,Ca2+内流,胞内Ca2+浓度升高,进而触发含胰岛素的囊泡释放胰岛素;其中,Ca2+对胰岛素分泌起着关键的触发作用[47]。

EDCs干扰胰岛素分泌的作用机理研究已取得一定进展,目前的研究主要集于环境雌激素化合物,包括天然雌激素和人工合成的雌激素化合物,干扰胰岛素分泌的潜在作用机理方面。研究证实,环境雌激素化合物可通过雌激素受体(ERs)途径,调节β细胞胰岛素合成[48]。已有证据证明,雌激素受体,包括雌激素核受体和膜受体参与调节胰岛素的分泌。雌激素核受体是属于甾体激素受体(steroid hormone receptor, SHR)超家族的成员,位于脑浆与胞核内,可与其天然雌激素配体17-β雌二醇(E2)结合,发生变构形成二聚体,然后与受体反应元件(estrogen response element, ERE)结合,刺激靶基因转录,从而调节雌激素促进细胞正常增生,分化和维持正常的生理功能[49]。雌激素核受体包含2种亚型:ERα和ERβ。研究证实2种雌激素核受体都可能参与环境化合物胰岛素分泌调节。此外一类新的雌激素受体,非典型性膜雌激素受体(non-classical membrane, ncmER)也被报道参与到胰岛素分泌调节中。ncmER其作用途径与传统雌激素核受体稍显不同:雌激素可以通过ncmER快速激活细胞内的第二信号系统,间接调节一系列基因的转录,从而促进胰岛β细胞分泌胰岛素[50]。G蛋白耦联受体(G protein-coupled estrogen receptor, GPR30)又称G蛋白耦联雌激素受体(GPER),是一种新型的膜雌激素受体,能与雌激素特异性结合并发挥生物学效应;研究证实GPER能够参与胰岛素的分泌调节[51]。

3.1 天然雌激素通过雌激素核、膜受体途径调节胰岛素分泌

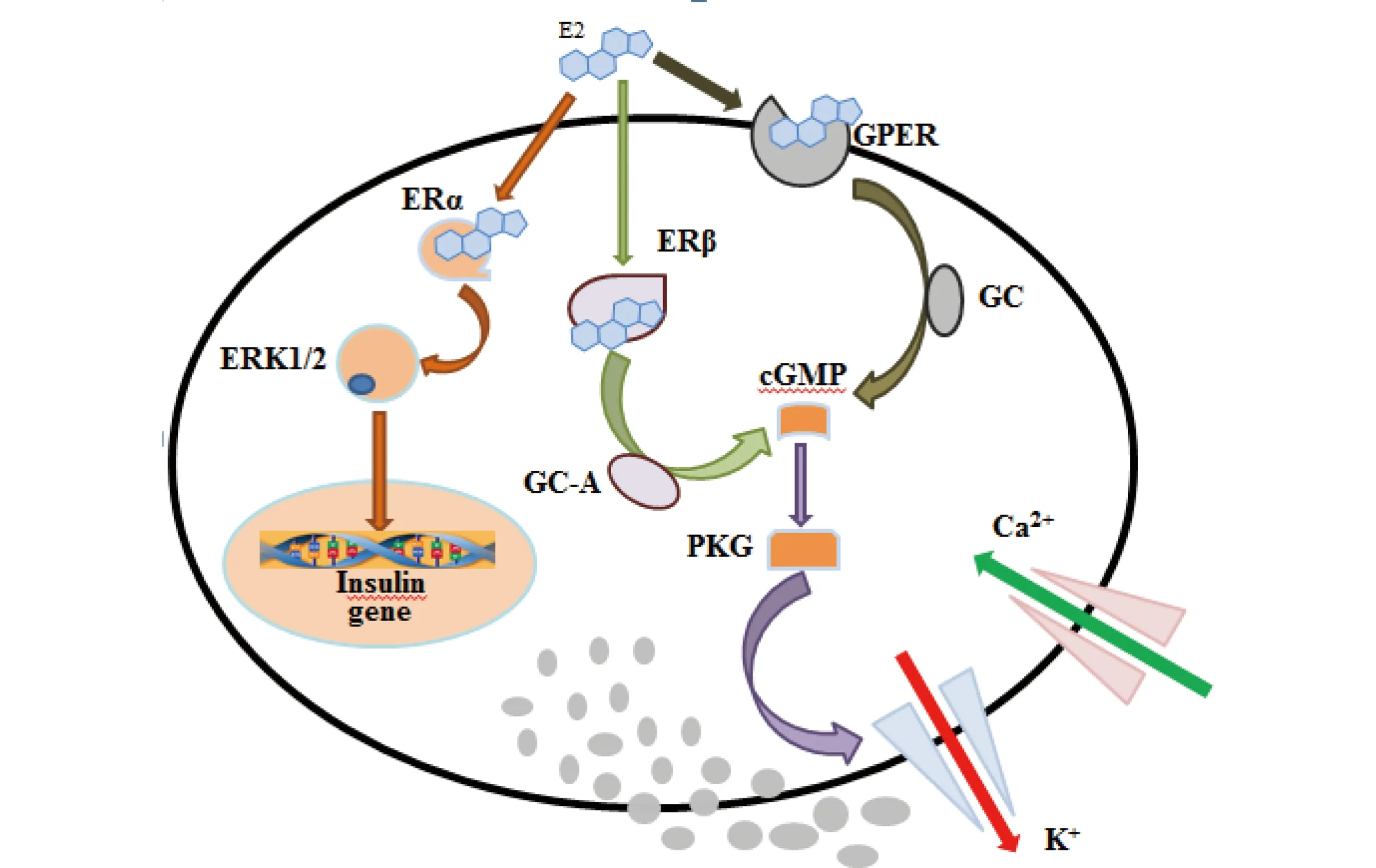

E2是典型的天然雌激素,目前研究证实E2可通过雌激素核、膜受体途径调节胰岛素分泌。Wong等[48]报道E2可通过非经典的ERα受体作用途径参与调节胰岛素的生物合成,其作用途径可简单描述为:E2结合细胞核外ERα,激活蛋白激酶ERK1/2途径,上调胰岛素基因insulin表达(见图1)。小鼠暴露于E2后,加入PPT(propylpyrazole triol,雌激素受体α特异性激动剂),能够显著提高体内胰岛素水平,且伴随有较高的胰岛素mRNA水平[26]。ERαKO(ERα基因缺陷型)小鼠模型进一步佐证非经典的ERα受体作用途径是E2调节胰岛素合成的主要途径[52]。此外,文献报道E2还可通过ERα途径影响β细胞的增殖与凋亡。例如E2通过ERα途径调节β细胞凋亡,ERαKO小鼠胰岛β细胞易受氧化损伤,导致细胞凋亡以及胰岛素分泌不足[34]。

此外,E2还可通过ERβ途径影响Ca2+通道,调节胰岛素分泌。其作用机理可能为:E2结合ERβ形成二聚体,二聚体激活心房利钠肽受体A(GC-A),增加Ca2+浓度,刺激β细胞分泌胰岛素[53](见图1)。经ERβ受体特异性激动剂DPN(2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionitrile)暴露的小鼠体内Ca2+以及胰岛素水平显著高于对照组;在敲除ERβ基因后,经DPN暴露的小鼠Ca2+浓度以及胰岛素水平与对照组相比无显著变化,证实了ERβ在胰岛素分泌调节中的重要作用[37]。

已有文献还比较了ERα和ERβ对胰岛素分泌的调节作用。Barros等[54]报道葡萄糖转运子-4 (Glut-4)作为主要的葡萄糖运载体,是细胞摄取葡萄糖的主要限速因子,在ERαKO小鼠体内检测到Glut-4含量显著降低;在ERβKO(ERβ基因缺陷型)小鼠体内,Glut-4含量无显著变化,证实Glut-4在细胞膜上的表达依赖于ERα受体,通过调节Glut-4可直接影响胰岛素的分泌。除此之外,利用ERαKO和ERβKO小鼠模型,证实在E2暴露情况下,ERα较ERβ对胰岛β细胞的保护作用更为显著[54]。

综上所述,在E2的作用下,ERα能够参与调节胰岛素的分泌量,并且对胰岛素β细胞具有保护作用;而ERβ主要是通过调控与胰岛素分泌相关的信号信使实现胰岛素的快速释放。

除此之外,E2还可通过新型受体GPER,调节胰岛素合成。GPER是一种功能性膜受体,能够与E2特异性结合。Sharma等[55]研究证实E2能够结合GPER,使Ca2+信号强度显著增强,胰岛素含量显著增加(见图1)。人工合成的GPER特异性配体G-1能够模拟E2刺激胰岛素合成,其作用机理可简单描述为G-1结合GPER,激活乌苷酸环化酶(GC),增加Ca2+浓度,促进胰岛素合成[35]。Kumar等[51]报道E2或G-1的存在能够分别增加环磷酸鸟苷(cGMP)以及磷酸酰肌醇(PI)的浓度,增加胰岛素分泌;当添加雌激素拮抗剂ICI182780与E2或G-1共同暴露后,高胰岛素效应消失,胰岛素分泌量与空白对照相比无显著变化;而当仅加入ICI182 780时,胰岛素分泌量显著降低,低于空白对照组,可见,GPR30可介导E2或G-1对胰岛素分泌的调节作用。此外,Liu等[56]还报道GPER在防止β细胞凋亡方面起着重要的作用,其特异性配体G-1能够模拟E2,减少胰岛β细胞凋亡[35]。对于其他的天然雌激素如雌酮、雌三醇目前的研究报道较少。

图1 β-雌二醇(E2)调节胰岛素分泌作用途径注:ERα、ERK1/2、ERβ、GC-A、cGMP、PKG、GPER、GC分别代表雌激素受体α、细胞外信号调节激酶1/2、雌激素受体β、鸟苷酸环化酶 A、环磷酸鸟苷、蛋白激酶G、G蛋白偶联雌激素受体、鸟苷酸环化酶。Fig. 1 Pathways of regulation of insulin secretion by 17β-Estradiolum (E2)Note: ERα, ERK1/2, ERβ, GC-A, cGMP, PKG, GPER and GC denote estrogen receptor α, extracellular signal regulated kinase1/2, estrogen receptor β, guanylate cyclase-A, cyclic guanosine monophosphate, protein kinase G, G-protein coupled estrogen receptor, guanylate cyclase.

3.2 人工合成的雌激素化合物干扰胰岛素分泌作用机理

与E2类似,人工合成的雌激素化合物BPA,具有高胰岛素效应,也可通过雌激素受体途径调节胰岛素合成以及β细胞凋亡,实现对胰岛素分泌的调节。研究表明,BPA能够结合ERα,激活ERK1/2激酶信号转导途径,通过非经典的ERα受体作用途径影响胰岛素合成[48]。BPA还能够与GPER结合,改变ATP/ADP,增加胞内Ca2+浓度,促进胰岛素合成[57]。Wei等[58]报道BPA暴露可调节胰腺十二指肠同源盒基因(pdx1)表达,该基因具有促进β细胞增殖以及抑制其凋亡的作用。

BPA是目前研究最多的具有胰岛素分泌干扰活性的类雌激素化合物,可通过模拟天然雌激素作用雌激素受体,干扰胰岛素分泌。其他具有高胰岛素效应的人工合成的雌激素化合物,如辛基酚和壬基酚,其胰岛素分泌干扰作用机理的报道较少。

环境内分泌干扰化合物除了通过雌激素受体途径干扰胰岛素分泌外,还有研究表明胰腺中存在雄激素受体(AR)[59],雄激素与雄激素受体结合后,可以通过转录活化下游基因,促进pdx1、葡萄糖转运子-2(Glut-2)蛋白表达和ERK1/2活性增加,产生促胰岛素分泌效应[60]。因此,EDCs可能通过AR途径调节胰岛素分泌。此外,一些文献报道EDCs还可通过芳香烃受体(AhR)途径、甲状腺素受体(TR)途径和糖皮质激素受体(GR)途径干扰胰岛β细胞分泌胰岛素[61-62]。除了受体途径,一些EDCs还可通过氧化应激途径作用胰岛β细胞,干扰胰岛素分泌[63-64],但相关报道较少,研究还有待深入。总之,对于EDCs干扰胰岛素分泌潜在作用机理的研究工作才刚刚起步,还有很多问题亟待研究解决。

4 展 望

综上所述,糖尿病作为一种典型的内分泌代谢系统疾病,患病人群数量众多,同时作为一种终身性、全身性疾病,治愈难度相对较大;威胁糖尿病患者的严重糖尿病并发症,更是给患者及其家庭、社会造成严重影响和负担。因此,研究糖尿病的发病机理,对于预防糖尿病、控制糖尿病发病率具有重要意义。本文主要从环境角度,通过流行病学调查建立环境内分泌干扰物暴露与糖尿病发病之间的相关性,证实环境内分泌干扰化合物暴露对胰岛β细胞胰岛素分泌的调节作用及其可能的作用机制,为现阶段糖尿病的防治提供参考,也为环境毒理学的研究提供新方向。

[1] 李剑, 马梅, 王子健. 环境内分泌干扰物的作用机理及其生物检测方法[J]. 环境监控与预警, 2010, 2(3): 18-25

Li J, Ma M, Wang Z J. Action mechanisms and bioassays of environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals [J]. Environmental Monitoring and Forewarnming, 2010, 2(3): 18-25 (in Chinese)

[2] 刘先利, 刘彬, 邓南圣. 环境内分泌干扰物研究进展[J]. 上海环境科学, 2003, 22(1): 57-62

Liu X L, Liu B, Deng N S. Study progress of environmental endocrine disruptors [J]. Shanghai Environmental Sciences 2003, 22(1): 57-62 (in Chinese)

[3] Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon J P, Giudice L C, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: An Endocrine Society scientific statement [J]. Endocrine Reviews, 2009, 30(4): 293-342

[4] Alonso-Magdalena P, Quesada I, Nadal A. Endocrine disruptors in the etiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus [J]. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2011, 7(6): 346-353

[5] 代庆红, 王忠东. 中国糖尿病的现状调查[J]. 中国医学指南, 2011, 9(13): 206-208

[6] 中华医学会糖尿病学分会. 中国2型糖尿病防治指南(2010年版)[J]. 中国糖尿病杂志, 2012, 20(1): 1-37

[7] Williams E D, Tapp R J, Magliano D J, et al. Health behaviors, socioeconomic status and diabetes incidence: The Australian Diabetes Obesity and Lifestyle Study [J]. Diabetologia, 2010, 53(12): 2538-2545

[8] Finucane M M, Stevens G A, Cowan M J, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: Systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country years and 9.1 million participants [J]. Lancet, 2011, 377(9765): 557-567

[9] Zimmet P, Alberti K G M M, Shaw J, et al. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic [J]. Nature, 2001, 414(6865): 782-787

[10] Carpenter D O. Environmental contaminants as risk factors for developing diabetes [J]. Reviews on Environmental Health, 2008, 23(1): 59-74

[11] vom Saal F S, Myers J P. Bisphenol A and risk of metabolic disorders [J]. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 2008, 300(11): 1353-1355

[12] Rignell-Hydbom A, Lidfeldt J, Kiviranta H, et al. Exposure to p,p'-DDE: A risk factor for type 2 diabetes [J]. PLoS one, 2009, 4: e7503

[13] Lin C Y, Chen P C, Lin Y C, et al. Association among serum perfluoroalkyl chemicals, glucose homeostasis, and metabolic syndrome in adolescents and adults [J]. Diabetes Care, 2009, 34(7): 702-707

[14] Lim J S, Lee D H, Jacobs D R Jr, et al. Association of brominated flame retardants with diabetes and metabolic syndrome in the U.S. population, 2003-2004 [J]. Diabetes Care, 2008, 31(9): 1802-1807

[15] Park S K, Son H K, Lee S K, et al. Relationship between serum concentrations of organochlorine pesticides and metabolic syndrome among non-diabetic adults [J]. Journey of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 2010, 43(1): 1-8

[16] Lee D H, Lee I K, Song K, et al. A strong dose-response relation between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and diabetes: Results from the National Health and Examination Survey 1999-2002 [J]. Diabetes Care, 2006, 29 (7): 1638-1644

[17] Everett C J, Frithsen I, Player M. Relationship of polychlorinated biphenyls with type 2 diabetes and hypertension [J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2011, 13(2): 241-251

[18] Uemura H, Arisawa K, Hiyoshi M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome associated with body burden levels of dioxin and related compounds among Japan's general population [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2009, 117(4): 568-573

[19] Lang I A, Galloway T S, Scarlett A, et al. Association of urinary bisphenol A concentration with medical disorders and laboratory abnormalities in adults [J]. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 2008, 300(11): 1303-1310

[20] Stahlhut R W, van Wijngaarden E, Dye T D, et al. Concentrations of urinary phthalate metabolites are associated with increased waist circumference and insulin resistance in adult U.S. males [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2007, 115(6): 876-882

[21] Hoppe A A, Carey G B. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers as endocrine disruptors of adipocyte metabolism [J]. Obesity, 2007, 15(12): 2942-2950

[22] Alonso-Magdalena P, Morimoto S, Ripoll C, et al. The estrogenic effect of bisphenol A disrupts pancreatic beta-cell function in vivo and induces insulin resistance [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2006, 114(1): 106-112

[23] Batista T M, Alonso M P, Vieira E, et al. Short -term treatment with bisphenol-A leads to metabolic abnormalities in adult male mice [J]. PloS one, 2012, 7(3): e33814

[24] Kamath V, Rajini P S. Altered glucose homeostasis and oxidative impairment in pancreas of rats subjected to dimethoate intoxication [J]. Toxicology, 2007, 231(2 3):137-146

[25] Muoio D M, Newgard C B. Molecular and metabolic mechanisms of insulin resistance and β-cell failure in type 2 diabetes [J]. Nat Rev, 2008, 9: 193-205

[26] Alonso-Magdalena P, Ropero A B, Carrera M P, et al. Pancreatic insulin content regulation by the estrogen receptor ERα [J]. PLoS oNE, 2008, 3(4): e2069

[27] Hectors T L M, Vanparys C, van der Ven K, et al. Environmental pollutants and type 2 diabetes: A review of mechanisms that can disrupt beta cell function [J]. Diabetologia, 2011, 54(6): 1273-1290

[28] Nadal A, Alonso-Magdalena P, Soriano S, et al. The pancreatic beta-cell as a target of estrogens and xenoestrogens: Implications for blood glucose homeostasis and diabetes [J]. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2009, 304(1-2): 63-68

[29] Prado C L, Pugh-Bemard A E, Elghazi L, et al. Ghrelin: Cells replace insulin-producing beta cells in two mouse models of pancreas development [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(9): 2924-2929

[30] Rutter G A. Nutrient-secretion coupling in the pancreatic islet β-cell: Recent advances [J]. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 2001, 22(6): 247-284

[31] Chen J Q, Brown T R, Russo J. Regulation of energy metabolism pathways by estrogens and estrogenic chemicals and potential implications in obesity associated with increased exposure to endocrine disruptors [J]. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 2009, 1793(7): 1128-1143

[32] Louet J F, LeMay C, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Antidiabetic actions of estrogen: Insights from humans and genetic mouse models [J]. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 2004, 6(3): 180-185

[33] Contreras J L, Smyth C A, Bilbao G, et al. 17beta-Estradiol protects isolated human pancreatic islets against proinflammatory cytokine-induced cell death: Molecular mechanisms and islet functionality [J]. Transplantation, 2002, 74(9): 1252-1259

[34] May C L, Chu K, Hu M, et al. Estrogens protect pancreatic β-cells from apoptosis and prevent insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus in mice [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(24): 9232-9237

[35] Balhuizen A, Kumar R, Amisten S, et al. Activation of G protein-coupled receptor 30 modulates hormone secretion and counteracts cytokine-induced apoptosis in pancreatic islets of female mice [J]. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2010, 320(1 2): 16-24

[36] Song L, Xia W, Zhou Z, et al. Low-level phenolic estrogen pollutants impair islet morphology and β-cell function in isolated rat islets [J]. Journal of Endocrinology, 2012, 215(2): 303-311

[37] Soriano1 S, Alonso-Magdalena1 P, García-Areívalo M, et al. Rapid insulinotropic action of low doses of bisphenol-A on mouse and human islets of Langerhans: Role of estrogen receptor β [J]. PLoS one, 2012, 7(2): e31109

[38] Newbold R R. Developmental exposure to endocrine disruptors and the obesity epidemic [J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2007, 23(3): 290-296

[39] Lin Y, Wei J, Li Y, et al. Developmental exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate impairs endocrine pancreas and leads to long-term adverse effects on glucose homeostasis in the rat [J]. American Journal of Physiology Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2011, 301(3): 527-538

[40] Gayathri N S, Dhanya C R, Indu A R, et al. Changes in some hormones by low doses of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP), a commonly used plasticizer in PVC blood storage bags and medical tubing [J]. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 2004, 119(4): 139-144

[41] Novelli M, Piaggi S, Tata V D. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced impairment of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in isolated rat pancreatic islets [J]. Toxicology Letters, 2005, 156(2): 307-314

[42] Piaggi S, Novelli M, Martino L, et al. Cell death and impairment of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion induced by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in the β-cell line INS-1E [J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2007, 220(3): 333-340

[43] Ghafour-Rashidi Z, Dermenaki-Farahani E, Aliahmadi A, et al. Protection by cAMP and cGMP phosphodiesterase inhibitors of diazinon-induced hyperglycemia and oxidative/nitrosative stress in rat Langerhans is lets cells: Molecular evidence for involvement of non-cholinergic mechanisms [J]. Pesticide Biochemistry Physiology, 2007, 87(3): 261-270

[44] Pournourmohammadi S, Ostad S N, Azizi E, et al. Induction of insulin resistance by malathion: Evidence for disrupted islets cells metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction [J]. Pesticide Biochemistry Physiology, 2007, 88(3): 346-352

[45] Livingstone C, Collison M. Sex steroids and insulin resistance [J]. Clinical Science, 2002, 102(2): 151-166

[46] Zsarnovszky A, Le H H, Wang H S, et al. Ontogeny of rapid estrogen-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in the rat cerebellar cortex: Potent nongenomic agonist and endocrine disrupting activity of the xenoestrogen bisphenol A [J]. Endocrinology, 2005, 146(12): 5388-5396

[47] 董永明, 张铭, 林显光, 等. 钙离子信号对胰岛素分泌的调控[J]. 现代生物医学进展, 2008, 8(5): 937-939

Dong Y M, Zhang M, Lin X G, et al. The mechanism of calcium signaling regulating insulin secretion [J]. Progress in Modern Biomedicine, 2008, 8(5): 937-939 (in Chinese)

[48] Wong W P, Tiano J P, Liu S, et al. Extranuclear estrogen receptor-alpha stimulates Neuro D1 binding to the insulin promoter and favors insulin synthesis [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010, 107(29): 13057-13062

[49] 赵晓民, 徐小明. 雌激素受体及其作用机制[J]. 西北农林科技大学学报: 自然科学版, 2004, 32(12): 154-158

Zhao X M, Xu X M. Estrogen receptor and its molecular mechanism [J]. Journal of Northwest A&F University (Natural Science Edition), 2004, 32(12): 154-158 (in Chinese)

[50] Chetana M R, Daniel F C, Larry A S, et al. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling [J]. Science, 2005, 307(5715): 1625-1630

[51] Kumar R, Balhuizen A, Amisten S, et al. Insulinotropic and antidiabetic effects of 17beta-estradiol and the GPR30 agonist G-1 on human pancreatic islets [J]. Endocrinology, 2011, 152(7): 2568-2579

[52] Park C J, Zhao Z, Glidewell-Kenney C, et al. Genetic rescue of nonclassical ERalpha signaling normalizes energy balance in obese ERalpha-null mutant mice [J]. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2011, 121(2): 604-612

[53] Soriano S, Ropero B A, Alonso-Magdalena P, et al. Rapid regulation of KATPchannel activity by 17β-estradiol in pancreatic β-cells involves the estrogen receptor β and the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor [J]. Molecular Endocrinology, 2009, 23(12): 1973-1982

[54] Barros R P, Machado U F, Warner M, et al. Muscle GLUT4 regulation by estrogen receptors ERβ and ERα [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(5): 1605-1608

[55] Sharma G, Prossnitz E R. Mechanisms of estradiol-induced insulin secretion by the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPR30/GPER in pancreatic beta-cells [J]. Endocrinology, 2011, 125(8): 3030-3039

[56] Liu S, Le May C, Wong W P, et al. Importance of extranuclear estrogen receptor-and membrane G protein-coupled estrogen receptor in pancreatic islet survival [J]. Diabetes, 2009, 58(10): 2292-2302

[57] Quesada I, Fuentes E, Viso-leon M C, et al. Low doses of the endocrine disruptor bisphenol-A and the native hormone 17β-estradiol rapidly activate transcription factor CREB [J]. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2002, 16(12): 1671-1673

[58] Wei J, Lin Y, Li Y, et al. Perinatal exposure to bisphenol A at reference dose predisposes offspring to metabolic syndrome in adult rats on a high-fat diet [J]. Endocrinology, 2011, 152(8): 1-12

[59] Diaz-Sanchez V, Morimoto S, Morales A, et al. Androgen receptor in the rat pancreas: Genetic expression and steroid regulation [J]. Pancreas, 1995, 11(3): 241-245

[60] 崔玉倩. 睾酮对胰岛β-细胞胰岛素分泌和凋亡的影响及机制[D]. 济南: 山东大学, 2012: 3-5

Cui Y Q. Effects and mechanisms of testosterone on glucose stimulated insulin secretion and cell apoptosis in β-cells [D]. Jinan: Shandong University, 2012: 3-5 (in Chinese)

[61] Fujiyoshi P T, Michalek J E, Matsumura F. Molecular epidemiologic evidence for diabetogenic effects of dioxin exposure in U.S. Air force veterans of the Vietnam war [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2006, 114(11): 1677-1683

[62] Sargis R M, Johnson D N, Choudhury R A, et al. Environmental endocrine disruptors promote adipogenesis in the 3T3-L1 cell line through glucocorticoid receptor activation [J]. Obesity, 2010, 18(7): 1283-1288

[63] Izquierdo-Vega J A, Soto C A, Sanchez-Pena L C, et al. Diabetogenic effects and pancreatic oxidative damage in rats subchronically exposed to arsenite [J]. Toxicology Letters, 2006, 160(2): 135-142

[64] Chen Y W, Huang C F, Tsai K S, et al. Methylmercury induces pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis and dysfunction [J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2006, 19(8): 1080-1085

◆

PotentialMechanismsofEffectsofEnvironmentalEndocrineDisruptingChemicalsonDisruptingInsulinSecretion

Han Shaolun1, Li Jian1,*, Wang Zijian2

1. Engineering Research Center of Groundwater Pollution Control and Remediation of Ministry of Education, College of Water Science, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China 2. Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100085, China

11 September 2013accepted11 November 2013

The increasing incidence of diabetes has attracted worldwide attention. The epidemiological survey shows significant correlation between increased incidence of diabetes and the rising use of environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). EDCs may increase the risk of diabetes, thus a dangerous factor causing diabetes. Under such background, this article reviewed the epidemiological relation between exposure of EDCs and outbreak of diabetes, the insulin-secretion regulation of EDCs in pancreatic β cells, its insulinotropic effects and potential action mechanisms. All of these suggest the importance of EDCs in inducing diabetes through its action mechanism of insulin-secretion regulation.

environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals; mechanisms; diabetes mellitus; insulin; estrogen receptor

国家自然科学青年基金(41001351);高等学校博士学科点专项科研基金资助课题(20100003120024)

韩绍伦(1988-),男,硕士,研究方向为生态毒理学,E-mail: hansl8804@hotmail.com;

*通讯作者(Corresponding author),E-mail: lijian@bnu.edu.cn

10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20130911002

韩绍伦,李剑, 王子健. 环境内分泌干扰化合物干扰胰岛素分泌潜在作用机理[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2014, 9(2): 181-189

Han S L, Li J, Wang Z J. Potential mechanisms of effects of environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals on disrupting insulin secretion [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2014, 9(2): 181-189 (in Chinese)

2013-09-11录用日期2013-11-11

1673-5897(2014)2-181-09

X171.5

A

李剑(1980—),女,环境科学博士,副教授,主要研究方向为生态毒理学,发表学术论文40余篇。