Retrohepatic vena cava deroof i ng in living donor liver transplantation for caudate hepatocellular carcinoma

2013-06-01

Hong Kong, China

Retrohepatic vena cava deroof i ng in living donor liver transplantation for caudate hepatocellular carcinoma

See Ching Chan, William W Sharr, Tan To Cheung, Albert CY Chan, Simon HY Tsang, Kenneth SH Chok, Kin Chung Leung and Chung Mau Lo

Hong Kong, China

The removal of tumor together with the native liver in living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma is challenged by a very close resection margin if the tumor abuts the inferior vena cava. This is in contrast to typical deceased donor liver transplantation where the entire retrohepatic inferior vena cava is included in total hepatectomy. Here we report a case of deroof i ng the retrohepatic vena cava in living donor liver transplantation for caudate hepatocellular carcinoma. In order to ensure clear resection margins, the anterior portion of the inferior vena cava was included. The right liver graft was inset into a Dacron vascular graft on the back table and the composite graft was then implanted to the recipient inferior vena cava. Using this technique, we observed the no-touch technique in tumor removal, hence minimizing the chance of positive resection margin as well as the chance of shedding of tumor cells during manipulation in operation.

hepatocellular carcinoma; liver transplantation

Introduction

Recipient survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is mainly compromised by tumor recurrence. Vascular invasion by HCC is the best predictor of tumor recurrence.[1]Although the entire native liver is excised from the transplant recipient, extrahepatic and frequently intrahepatic (47%) disease recurrence is the mode of treatment failure.[2]Dissemination of tumor cells before transplantation can be occult and may escape detection despite thorough search by imaging. Furthermore, tumor cells dissemination during total hepatectomy of the native liver can also occur and should be avoided.

In living donor liver transplantation, the partial liver graft obtained from the donor does not include the inferior vena cava (IVC). Therefore, "total" hepatectomy of the native liver in the recipient is IVC-sparing. This is in contrast to total hepatectomy in deceased donor liver transplantation. Thus, more manipulation of the HCC-containing native liver can be expected. As the hepatic veins are short, tumors which are in close proximity to the IVC, even without invasion of the liver capsule and adventitia, are only a few millimeters away from the circulation of the IVC. Separation of the liver from the retrohepatic IVC requires isolation, ligation, and division of these short hepatic veins. There is also no reliable way of determining the absence of involvement of these veins.En blocremoval of the retrohepatic IVC, which is attached to the caudate liver, should minimize the chance of tumor cell dissemination during native liver total hepatectomy. Here we describe how this was performed in conjunction with using a right liver graft with the middle hepatic vein. Reconstruction of artif i cial venous graft is also explained.

Surgical technique

The patient was a 63-year-old man, a hepatitis B virus carrier with Child-Pugh B cirrhosis. Surveillance for HCC revealed an elevation of serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level to 37 ng/mL. Computed tomography of the liver demonstrated a 5.3×5.6×4.9 cm HCC in segment 8 and the caudate lobe, abutting but not invading the right (Fig. 1A), middle (Fig. 1B) and left (Fig. 1C) hepatic veins and the IVC. Dual-tracer positron emission tomography (18F-FDG &11C-acetate) showed moderate uptake of11C-acetate (SUVmax 10.7) and mild patchy uptake of FDG (SUVmax 4.7). The constellation of fi ndings was suggestive of HCC with relatively well-differentiated pathology.[3]There were no hypermetabolic satellite diseases in the remaining liver or regional lymphadenopathy. Neither was there any FDG- or11C acetate-avid lesion found in the survey of the remaining body to suggest extrahepatic lesions.

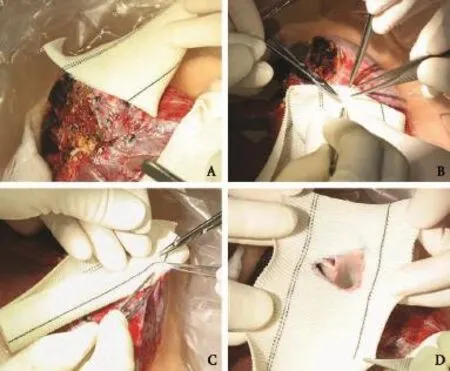

As his liver function was compromised and prohibited a major hepatectomy, the patient underwent living donor liver transplantation. The native liver total hepatectomy was performed with mobilization of the right and left liver. The common bile duct, hepatic arteries and portal veins were isolated and divided. The infrahepatic IVC was controlled with a Rommel tourniquet and the suprahepatic IVC by an Ulrich-Swiss clamp. The native liver was not separated from the IVC but was delivereden blocwith the anterior wall of the retrohepatic IVC. A 5 cm long and 3 cm wide defect of the anterior aspect of the IVC was formed (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.Computed tomography scans in portal venous phase showing the HCC abutting the right (A), middle (B) and left (C) hepatic veins and IVC.

The right liver graft obtained from the living donor underwent venoplasty of the middle and right hepatic veins, and a triangular venous cuff[4]of base 20 mm and height 20 mm was fashioned. The graft weighed 546 g and accounted for 51% of the standard liver volume[5]of the recipient. A woven double velour polyester vascular graft (Hemashield Platinum™, Boston Scientif i c Meditech, NJ, USA) 24 mm in diameter was slit open and a triangular opening of the same dimension with the apex of the middle hepatic vein pointing to the left was made. The single triangular venous cuff was sutured to the corresponding triangular opening in the vascular graft with 5/0 Prolene continuous suture (Fig. 3). As the vascular graft was not stretchable, it was reduced to a size slightly larger than the defect of the IVC and the inferior portion slightly longer. The insetting of the vascular graft with the liver graft to the IVC was started with the right side and completed on the left side with 5/0 Prolene continuous suture (Fig. 2B). Postoperativeaspirin at 100 mg daily per oral was prescribed to reduce the chance of thrombosis.

Fig. 2.The rectangular defect of the anterior wall of the IVC after total hepatectomy of the native liver (A). Right liver graft including the middle hepatic vein reconstructed with vascular graft implanted (B).

Fig. 3.Insetting of the single triangular venous cuff of the middle and right hepatic veins to the Dacron vascular graft.

Fig. 4.Photomicrograph showing the HCC in close proximity to the intact liver capsule (A). Photomicrograph showing focal vascular invasion of HCC (B).

Fig. 5.Computed tomography scans in portal venous phase showing patient right (A) and middle (B) hepatic veins and the IVC.

Histological examination of the explanted liver revealed a 2.6×1.5×1.0 cm encapsulated well-differentiated HCC (Fig. 4A). Foci of lymphovascular permeation by tumor cells were noted (Fig. 4B). The capsule was nevertheless intact (Fig. 4A). Computed tomography in portal venous phase nine months after transplantation showed patent right (Fig. 5A) and middle (Fig. 5B) hepatic veins. There was no recurrence of HCC two years after transplantation and the serum AFP level remained below 3 ng/mL.

Discussion

The primary purpose of using this patch was to achieve tumor clearance with widest possible posterior margins and with less manipulation of the HCC-containing native liver. The no-touch technique was fi rst propagated for removal of colonic cancer by Turnbull.[6]This principle is applied to hepatectomy for HCC with the anterior approach and was validated to improve survival for stage-II disease.[7]

The insetting of the vascular graft patch onto the deroofed IVC nevertheless requires attention to the reconstruction of the IVC in conjunction with hepatic vein anastomosis. It is important to orientate the graft with the attached patch anticipating a neutral position along the axis of the IVC. Given the mobilized portion of the suprahepatic and infrahepatic IVC, this degree of freedom provides some latitude for mismatch of the form of the graft and the right subdiaphragmatic space. The posterior wall of the retrohepatic IVC conserved is expandable to preserve the physiological function of the vena cava.

Total hepatectomy including the IVC and replacement of the IVC with a ringed polytetraf l uoroethylene graft had been described.[8]This technique does not have the advantage of a patch as described above. The replacement by a deceased donor IVC graft[9]is limited by the availability of donated livers. The use of patched hepatic vein for anastomosis to the IVC had been described before. The cryopreserved superior vena cava vein is opened and used as a large patch with its tributaries anastomosed to the hepatic veins of the graft. The patch is sutured to the recipient's common orif i ce of the hepatic veins.[10]We found this is not necessary since direct anastomosis is the least prone to impediment of venous outf l ow. It is important to note that side-to-side anastomosis of the IVC by side clamping had been described.[11,12]In this case, though the IVC-to-graft anastomosis was side to side, the remnant IVC was not wide enough for side clamping.

The indication for liver transplantation for HCC varies. Some groups consider it feasible to transplant patients with no major vascular invasion with size and number of tumors much beyond common practice,[13]but the way in which the native liver that contains the tumor is excised is not addressed. One must not be persuaded to transplant patients with tumors beyond tested criteria only because of the feasibility of this technique, which at best approaches the way of total hepatectomy in deceased donor liver transplantation.

In conclusion, deroof i ng the IVC with replacement with a vascular graft is feasible. Conf i rmation of the oncological advantage of this technique requires a big cohort of patients with HCC in close proximity to the IVC treated with this technique. The current evidence at least substantiates its further application.

Contributors:CSC drafted the manuscript; SWW, CTT, CACY, TSHY and CKSH revised the manuscript; LKC examined and updated the history of the specimen; LCM revised and approved the manuscript. CSC is the guarantor.

Funding:This study was supported by a grant from Li Shu Fan Medical Foundation.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benef i ts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Mariani L, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:35-43.

2 Roayaie S, Schwartz JD, Sung MW, Emre SH, Miller CM, Gondolesi GE, et al. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplant: patterns and prognosis. Liver Transpl 2004;10:534-540.

3 Ho CL, Chen S, Yeung DW, Cheng TK. Dual-tracer PET/CT imaging in evaluation of metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med 2007;48:902-909.

4 Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Wong J. Hepatic venoplasty in livingdonor liver transplantation using right lobe graft with middle hepatic vein. Transplantation 2003;75:358-360.

5 Urata K, Kawasaki S, Matsunami H, Hashikura Y, Ikegami T, Ishizone S, et al. Calculation of child and adult standard liver volume for liver transplantation. Hepatology 1995;21:1317-1321.

6 Turnbull RB Jr, Kyle K, Watson FR, Spratt J. Cancer of the colon: the inf l uence of the no-touch isolation technic on survival rates. Ann Surg 1967;166:420-427.

7 Liu CL, Fan ST, Cheung ST, Lo CM, Ng IO, Wong J. Anterior approach versus conventional approach right hepatic resection for large hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomized controlled study. Ann Surg 2006;244:194-203.

8 Matsuda H, Sadamori H, Shinoura S, Umeda Y, Yoshida R, Satoh D, et al. Aggressive combined resection of hepatic inferior vena cava, with replacement by a ringed expanded polytetraf l uoroethylene graft, in living-donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010;17:719-724.

9 Chen CL, Concejero AM, Wang CC, Wang SH, Liu YW, Yang CH, et al. Inferior vena cava replacement in living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2009;15:1637-1640.

10 Hashimoto T, Sugawara Y, Kishi Y, Akamatsu N, Matsui Y, Kokudo N, et al. Superior vena cava graft for right liver and right lateral sector transplantation. Transplantation 2005;79: 920-925.

11 Belghiti J, Panis Y, Sauvanet A, Gayet B, Fékété F. A new technique of side to side caval anastomosis during orthotopic hepatic transplantation without inferior vena caval occlusion. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1992;175:270-272.

12 Mehrabi A, Mood ZA, Fonouni H, Kashf i A, Hillebrand N, Müller SA, et al. A single-center experience of 500 liver transplants using the modif i ed piggyback technique by Belghiti. Liver Transpl 2009;15:466-474.

13 Takada Y, Uemoto S. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: the Kyoto experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010;17:527-532.

Received February 16, 2012

Accepted after revision January 19, 2013

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2013;12:552-555)

AuthorAff i liations:Department of Surgery (Chan SC, Sharr WW, Cheung TT, Chan ACY, Tsang SHY, Chok KSH and Lo CM); State Key Laboratory for Liver Research (Chan SC and Lo CM), and Department of Pathology (Leung KC), The University of Hong Kong, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China

See Ching Chan, MS, PhD, Li Shu Fan Medical Foundation Professor in Surgery, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China (Tel: 852-22553025; Fax: 852-28165284; Email: seechingchan@gmail.com)

© 2013, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(13)60087-9

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Simultaneous recovery of dual pathways for ammonia metabolism do not improve further detoxif i cation of ammonia in HepG2 cells

- Optimal central venous pressure during partial hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma

- Risk factors and clinical characteristics of portal vein thrombosis after splenectomy in patients with liver cirrhosis

- Fine needle aspirating and cutting is superior to Tru-cut core needle in liver biopsy

- Diagnostic accuracy of enhanced liver fi brosis test to assess liver fi brosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C

- Mattress sutures for the modif i cation of end-toend dunking pancreaticojejunostomy