Giant cell tumor of the pancreas: a pathological diagnosis with poor prognosis

2010-12-14AshishSinghalStanShragoShiFengLiYiHuangandVivekKohli

Ashish Singhal, Stan S Shrago, Shi-Feng Li, Yi Huang and Vivek Kohli

Oklahoma, USA

Giant cell tumor of the pancreas: a pathological diagnosis with poor prognosis

Ashish Singhal, Stan S Shrago, Shi-Feng Li, Yi Huang and Vivek Kohli

Oklahoma, USA

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010; 9: 433-437)

pancreas;giant cell;osteoclast;pleomorphic;neoplasm

Introduction

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) of the pancreas are rare, highly malignant, non-endocrine tumors,which account for less than 1% of all pancreatic malignancies.[1-3]They usually present as a large cystic pancreatic mass with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.Histologically, they are classi fi ed into osteoclast-like giant cell tumor (OGCT), pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma(PGCC), or a mixed type.[2,3]Whenever possible, en-bloc surgical resection is the only appropriate treatment for them. Limited data suggest that OGCT is less aggressive and may have a better prognosis compared to either PGCC or pancreatic adenocarcinoma.[2]We report two cases of GCTs of the pancreas, one each of PGCC and OGCT, who underwent en-bloc surgical resection.

Case reportsCase 1

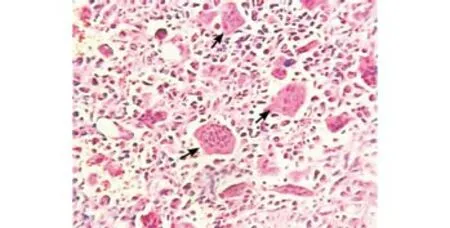

A 62-year-old man presented with upper abdominal and left-sided back pain and nausea for the last 4 months.On physical examination, mild tenderness was noted in the epigastrium and the left hypochondrium. An abdominal mass was palpable in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. Serum chemistry, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen (CA19-9) were within normal limits. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) revealed a large heterogenous lesion (13×12×11 cm) in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, extending from the greater curvature of the stomach to the transverse colon, involving the splenic hilum and the tail of the pancreas (Fig. 1). CT-guided core needle biopsy suggested an undifferentiated malignant neoplasm. En-bloc distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy and colonic resection was performed.Gross pathological examination showed a large pseudoencapsulated tumor (15×15×10 cm) arising from the tail of the pancreas, densely adhered to the splenic hilum. The tumor was solid, and had a variegated, red-grey-yellowish appearance on the cut surface indicating areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, the tumor revealed a triphasic population of cells: mitotic mononuclear round cells, abundant osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells with central nucleoli, and spindle cells. Osteoid deposition was seen in a random pattern (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemistry was diffusely positive for vimentin, negative for cytokeratin, and all giant cells stained positive for CD68. The postoperative recovery was uneventful. No additional adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy was administered. At 6 months after surgery, the patient remained disease-free with no clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence.

Fig. 1. CECT of the abdomen showing a large heterogenous lesion abutting the greater curvature of the stomach, splenic hilum, and tail of the pancreas.

Fig. 2. HE staining: arrows show an osteoclast-like giant cell.

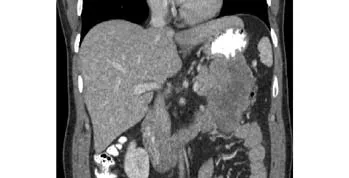

Fig. 3. CECT of the abdomen: coronal section showing a large heterogenous lesion arising from the tail of the pancreas causing a mass effect on the colon.

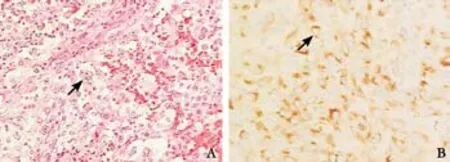

Fig. 4. Arrow showing a pleomorphic giant cell. A: HE staining; B:Cytokeratin positivity.

Case 2

A 42-year-old man presented with left upper abdominal pain referred to his left shoulder, with nausea and early satiety for two months. He had been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis 5 years previously and remained well-controlled on medications. On physical examination,a non-tender mass was noted occupying the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. The laboratory data were within normal limits. Serum concentrations of the tumor markers CEA and CA19-9 were 1.2 ng/ml (normal: <2.5 ng/ml) and 92 U/ml (normal: <37 U/ml), respectively.CECT examination revealed a large heterogenous lesion(8.4×6.7×6.0 cm) arising from the tail of the pancreas resulting in a mass effect on the adjacent splenic fl exure of the colon, stomach, and 4th part of the duodenum (Fig.3). An en-bloc resection was performed of the distal pancreas, spleen, stomach with attached omentum, and 13.5 cm of colon.

Gross pathological examination identi fi ed a large circumscribed pseudoencapsulated tumor (14×7×7 cm) in the tail of the pancreas, densely adhered to the serosal surface of the stomach. The tumor had a solid,variegated, tan-red-gray cut surface. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, the tumor was composed of densely cellular and compact proliferation of undifferentiated malignant cells. The nuclei were large, pleomorphic with coarse granular chromatin, prominent nucleoli,and abundant mitoses. Cells with multiple nuclei gave a "giant cell-like" appearance (Fig. 4A). Occasional foci of typical glandular differentiation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma were observed. Immunohistochemical studies showed that the tumor was diffusely and strongly positive for cytokeratin (Fig. 4B). The postoperative recovery was uneventful; however, the patient died 4 months later due to diffuse pulmonary metastasis.

Discussion

Sommers and Meissner[1]fi rst reported the pathological features of GCTs. These tumors usually present in the 6th or 7th decade of life with a nearly equal gender ratio,although younger patients have been reported.[4,5]They have some pathological features different from those of common ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas.[6]GCTs of the pancreas mostly involve the body and tail of the pancreas in contrast to pancreatic adenocarcinoma(PAC) that mainly involves the head. Nonspeci fi c upper abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and a palpable mass are the prominent initial symptoms in patients with GCTs, whereas jaundice is the most common presentation in patients with PAC. This is attributable to the frequent location of GCTs in the body or tail of the pancreas.Abdominal pain as a primary symptom is likely related to the growth of the tumor to a giant mass or perineural invasion. Sixty percent of the tumors were noted to be greater than 6 cm at the time of initial diagnosis, the largest reported being 24.5 cm.[7]Despite their large size,GCTs of the pancreas do not show vascular invasion.[8]Elevation of tumor markers (CEA and CA19-9) are less frequent in GCTs than in PACs; however, no signi fi cant differences were found. The sensitivities of abdominal ultrasonography, CECT, magnetic resonance imaging,and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) are similar to those for PAC in detecting these tumors. In most patients, CT scan reveals an irregular hypodense mass.[6]In general, PACs appear hypovascular on contrast CT scan; however, more than 50% of GCTs of the pancreas are hypervascular, possibly related to rapid growth or in fl ammatory reaction. The levels of in fl ammatory markers like white blood cell count, C-reactive protein,and interleukin are increased in >50% of cases with GCT of the pancreas.[6,7]In a series of fi ve patients reported by Moore et al[8]EUS-guided fi ne-needle aspiration cytology(FNAC) established the diagnosis in each patient. EUS appearance differed from that of typical PAC and neuroendocrine tumors. GCTs tend to be larger and appear markedly heterogeneous with well-demarcated hyperechoic and hypoechoic areas closely opposed within the same lesion.[8]Cytological features on FNAC can separate primary giant cell-containing neoplasms from non-neoplastic giant cell-containing lesions of the pancreas and giant cell-containing neoplasms not arising within the pancreas.[9]

GCTs have been divided into two subtypes: OGCT,which morphologically resembles benign-appearing giant cells seen in giant cell tumor of bone, and PGCC consisting of bizarre, pleomorphic, and multinucleatedgiant cells.[2,3]Considering the signi fi cant overlap of descriptions in the pathology literature for these neoplasms, a recent World Health Organization classiif cation clumps the two subtypes in a single category designated as undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclastlike giant cells.[10]PGCC is postulated to originate from ductal epithelial cells based on light microscopy,electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and its frequent association with ductal carcinoma.[11]The positivity of pleomorphic giant cells (mononuclear and multinucleated forms) for low molecular weight cytokeratin, lack of reactivity for CD68 and vimentin, and accompanying elevated serum CA19-9 levels con fi rms their epithelial nature.[4]In contrast, the histogenesis of OGCT is controversial with most authors favoring an epithelial derivation from acinar cells or ductal cells while few support a mesenchymal origin.[4,10,12-14]An epithelial derivation has been proposed on the basis of morphological and ultrastructural fi ndings of the giant cells and CEA and keratin positivity on immunohistochemical studies.[2,12,14]In contrast, the bland nuclear features, positivity for CD68 and vimentin,and negativity for low molecular weight cytokeratin favor a mesenchymal or histiocytic origin.[4]The giant cells are also strongly positive for KP-1, a monoclonal antibody marker for the monocyte/macrophage lineage. However,the cell giving rise to OGCT remains elusive. Goldberg et al[15]suggested that circulating monocytic stem cells may be stimulated by local factors or tumor-derived factors such as cytokines to proliferate and differentiate into osteoclast-like giant cells.

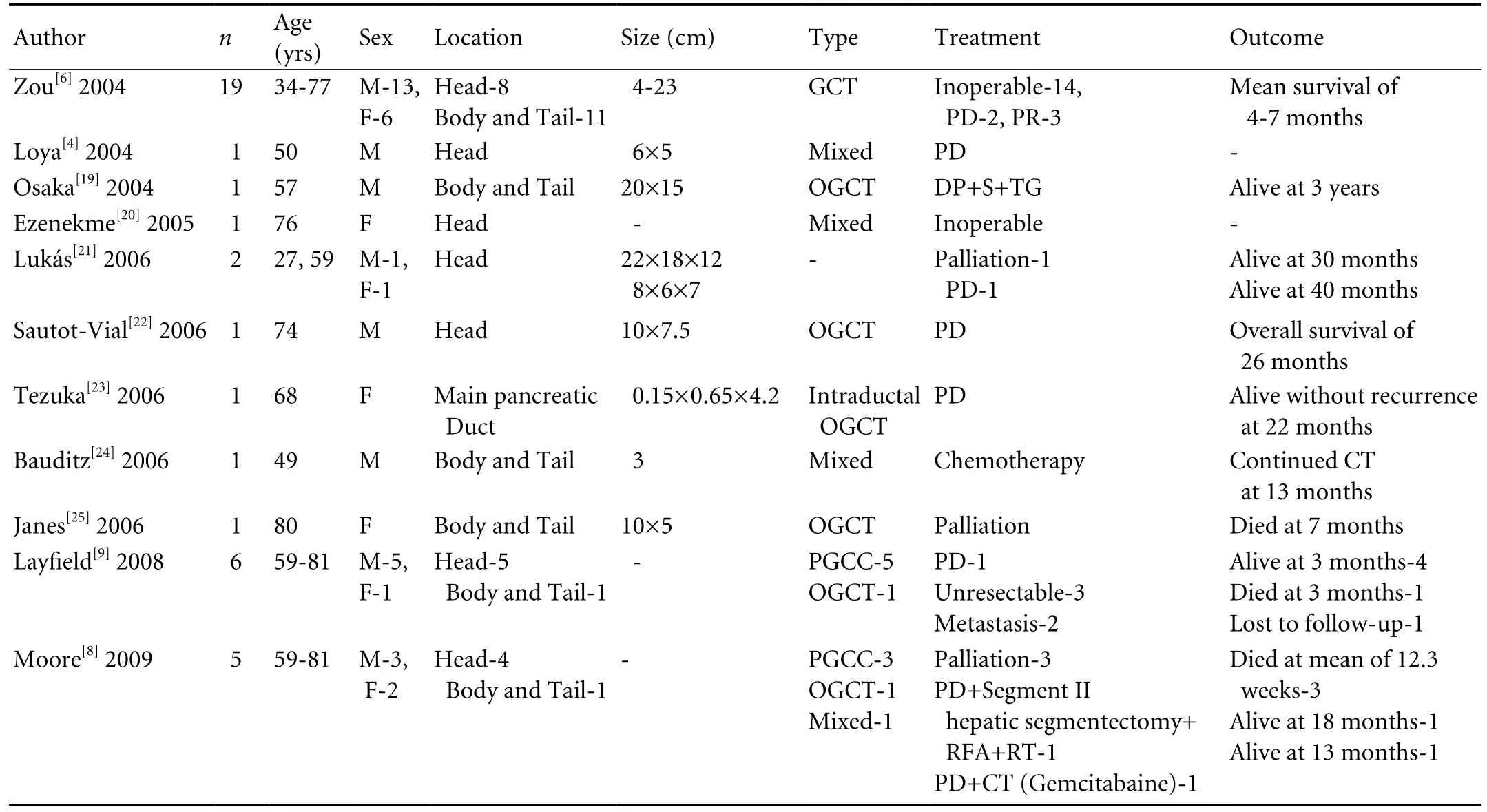

Table. Literature review of GCT of the pancreas published between 2004 and 2009

En-bloc surgical resection is an appropriate treatment for these tumors. However, it may not always be feasible as more than half of GCTs are unresectable by the time of presentation due to large size, local invasion, or intraabdominal metastases. This is more often noted with PGCC.[4,10]Like giant cell tumors (osteoclast type) of other organs such as the liver, thyroid, parotid gland, and breast, OGCT of the pancreas appears to have a better prognosis than PGCC because it is slower to metastasize,and rarely metastasizes to the lymph nodes.[2-4,8,10,13-16]A review of the literature revealed that the interval to death or disease progression ranges from 4 months to 10 years.[6-8,10,16]The overall median survival is 11 months,decreasing to 6.5 months in unresectable lesions.[4,10,17]Table illustrates the clinical, pathological, treatment, and follow-up details of patients with GCT of the pancreas published in English between 2004 and 2009. Considering the epithelial origin of the neoplastic population of cells, it would be reasonable to expect a response to chemotherapeutic agents and radiotherapy; however, there is no large experience and objective evidence is lacking.[10]Sporadic case reports have demonstrated reduction in tumor mass and prolongation of survival after treatment with 5- fl uorouracil.[17]It may be reasonable to consider agents such as gemcitabine for palliation.[18]Extrapolating from the radiosensitivity of giant-cell tumors of bone, we may anticipate bene fi ts of radiation in the neo-adjuvant setting; however, there is only one report of a decrease in tumor volume and associated tumor markers.[17]

In conclusion, GCTs are a rare malignant lesion of the pancreas with indistinct clinical or radiological characteristics. There is a little difference between the two subtypes according to our two cases and the literature, and their prognosis is probably no better than that of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Surgical removal is the only appropriate treatment. Responses to chemotherapy or radiotherapy remain undocumented.More studies are required to document management approaches and outcomes.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: INTEGRIS approved this study.

Contributors: SA wrote the fi rst draft of this commentary. All authors contributed to the intellectual context and approved the fi nal version. KV is the guarantor.

Competing interest: No bene fi ts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Sommers SC, Meissner WA. Unusual carcinoma of the pancreas. Arch Pathol 1954;58:101-111.

2 Cubilla AL, Fitzgerald PJ. Tumors of the exocrine pancreas.Atlas of Tumor Pathology, 2nd series, fascicle 19. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology;1984:155-167.

3 Deckard-Janatpour K, Kragel S, Teplitz RL, Min BH,Gumerlock PH, Frey CF, et al. Tumors of the pancreas with osteoclast-like and pleomorphic giant cells: an immunohistochemical and ploidy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998;122:266-272.

4 Loya AC, Ratnakar KS, Shastry RA. Combined osteoclastic giant cell and pleomorphic giant cell tumor of the pancreas:a rarity. An immunohistochemical analysis and review of the literature. JOP 2004;5:220-224.

5 Molberg KH, Heffess C, Delgado R, Albores-Saavedra J.Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells of the pancreas and periampullary region. Cancer 1998;82:1279-1287.

6 Zou XP, Yu ZL, Li ZS, Zhou GZ. Clinicopathological features of giant cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2004;3:300-302.

7 Jotsuka T, Hirota M, Tomioka T, Ohshima H, Katsumori T,Miyanari N, et al. Giant cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas 1999;18:415-417.

8 Moore JC, Hilden K, Bentz JS, Pearson RK, Adler DG.Osteoclastic and pleomorphic giant cell tumors of the pancreas diagnosed via EUS-guided FNA: unique clinical, endoscopic,and pathologic fi ndings in a series of 5 patients. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:162-166.

9 Lay fi eld LJ, Bentz J. Giant-cell containing neoplasms of the pancreas: an aspiration cytology study. Diagn Cytopathol 2008;36:238-244.

10 Leighton CC, Shum DT. Osteoclastic giant cell tumor of the pancreas: case report and literature review. Am J Clin Oncol 2001;24:77-80.

11 Watanabe M, Miura H, Inoue H, Uzuki M, Noda Y, Fujita N,et al. Mixed osteoclastic/pleomorphic-type giant cell tumor of the pancreas with ductal adenocarcinoma: histochemical and immunohistochemical study with review of the literature.Pancreas 1997;15:201-208.

12 Trepeta RW, Mathur B, Lagin S, LiVolsi VA. Giant cell tumor("osteoclastoma") of the pancreas: a tumor of epithelial origin.Cancer 1981;48:2022-2028.

13 Lewandrowski KB, Weston L, Dickersin GR, Rattner DW,Compton CC. Giant cell tumor of the pancreas of mixed osteoclastic and pleomorphic cell type: evidence for a histogenetic relationship and mesenchymal differentiation.Hum Pathol 1990;21:1184-1187.

14 Rosai J. Carcinoma of pancreas simulating giant cell tumor of bone. Electron-microscopic evidence of its acinar cell origin.Cancer 1968;22:333-344.

15 Goldberg RD, Michelassi F, Montag AG. Osteoclast-like giant cell tumor of the pancreas: immunophenotypic similarity to giant cell tumor of bone. Hum Pathol 1991;22:618-622.

16 Jeffrey I, Crow J, Ellis BW. Osteoclast-type giant cell tumour of the pancreas. J Clin Pathol 1983;36:1165-1170.

17 Drexler LJ, Mitre RJ, Madan E, Zidar BL. Pancreatic giant cell carcinoma of the osteoclastic type: response to 5- fl uorouracil and radiation. Am J Gastroenterol 1986;81:1093-1097.

18 Mercer PM, McCabe MM, Murphy JJ. Recurrence of osteoclastlike giant cell carcinoma of the pancreas after 10 years. Aust N Z J Surg 1996;66:334-335.

19 Osaka H, Yashiro M, Nishino H, Nakata B, Ohira M, Hirakawa K. A case of osteoclast-type giant cell tumor of the pancreas with high-frequency microsatellite instability. Pancreas 2004;29:239-241.

20 Ezenekwe AM, Collins BT, Ponder TB. Mixed osteoclastic/pleomorphic giant cell tumor of the pancreas: a case report.Acta Cytol 2005;49:549-553.

21 Lukás Z, Dvorák K, Kroupová I, Valásková I, Habanec B.Immunohistochemical and genetic analysis of osteoclastic giant cell tumor of the pancreas. Pancreas 2006;32:325-329.

22 Sautot-Vial N, Rahili A, Karimdjee-Soihili B, Benizri E,Avallone S, Benchimol D. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic:Osteoclast-like giant cell tumor of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;21:1072.

23 Tezuka K, Yamakawa M, Jingu A, Ikeda Y, Kimura W. An unusual case of undifferentiated carcinoma in situ with osteoclast-like giant cells of the pancreas. Pancreas 2006;33:304-310.

24 Bauditz J, Rudolph B, Wermke W. Osteoclast-like giant cell tumors of the pancreas and liver. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:7878-7883.

25 Janes S, Cid J, Kaye P, Doran J. Pancreatic osteoclastoma:immunohistochemical evidence of a reactive histiomonocytic origin. ANZ J Surg 2006;76:198-199.

BACKGROUND: Giant cell tumors are rare and highly malignant tumors of the pancreas. Based on two distinct cell populations, they have been divided into two subtypes corresponding to the osteoclast-like giant cell tumor and the pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Distinctive imaging features of the tumors remain uncharacterized.Surgical removal is the only appropriate treatment for them,but responses to chemotherapy or radiotherapy remain undocumented.

METHODS: Clinical, radiological, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical features of two cases of giant cell tumor of the pancreas are presented along with a brief review of the literature.

RESULTS: En-bloc resection was done successfully in both cases. The patient with an osteoclast-like giant cell tumor remained disease-free with no clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence at 6 months after surgery. However, the patient with the pleomorphic type died 4 months later due to diffuse pulmonary metastasis.

CONCLUSIONS: En-bloc surgical resection is the only appropriate treatment for giant cell tumors. The overall prognosis of these tumors is poorer than that of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, especially the pleomorphic type.More studies are required to document the management and outcomes of the tumors.

Author Af fi liations: Nazih Zuhdi Transplant Institute (Singhal A, Li SF,Huang Y and Kohli V), Department of Pathology (Shrago SS), INTEGRIS Baptist Medical Center, 3300 NW Expressway, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73112, USA

Vivek Kohli, MD, Nazih Zuhdi Transplant Institute,INTEGRIS Baptist Medical Center, 3300 NW Expressway, Oklahoma City,Oklahoma 73112, USA (Tel: 001-405-949-3349; Fax: 001-405-945-5844;Email: Vivek.Kohli@gmail.com)

© 2010, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

January 18, 2010

Accepted after revision June 9, 2010

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Total laparoscopic hysterectomy after liver transplantation

- Pancreatic duct stones in patients with chronic pancreatitis: surgical outcomes

- Letters to the Editor

- Outcomes and mechanisms of ischemic preconditioning in liver transplantation

- Percutaneous injection of hemostatic agents for active liver hemorrhage

- Application of a medical image processing system in liver transplantation