Receiving antenatal care via mobile clinic: Lived experiences of Jordanian mothers

2023-05-14HlBwiAsmAuAeZiAlHmnSfAlzui

Hl A.Bwi ,Asm’ S.Au Ae ,Zi M.Al-Hmn ,Sf M.Alzui

a Maternal and Child Health Department,School of Nursing the University of Jordan,Amman,Jordan

b National Women Health Center (resigned),Royal Medical Services,Amman,Jordan

c Faculty of Nursing Jordan University of Science and Technology,Irbid,Jordan

d Royal Medical Services,Amman,Jordan

Keywords: Jordan Mobile health units Pregnancy Pregnant women Prenatal care Qualitative research

ABSTRACT Objective:To understand the perceptions of pregnant Jordanian women who received antenatal care via mobile clinic,and to contribute new insights into the experiences of these mothers and how they evaluated the services that were available.Methods:Ten Jordanian mothers who had received antenatal care at a mobile clinic discussed their experiences in semi-structured,audiotaped interviews in a study that adopted a qualitative research design.The analysis was done using interpretative phenomenological analysis.Results:Three main themes were identified:Being informed about the medical campaign or missing the opportunity of being informed;The experience of receiving antenatal care was wonderful,although there was only one thing lacking;and they safeguard our life and take any opportunity to educate us.Conclusion:Data indicate that the mothers were largely satisfied with most facets of the antenatal care services they had received at the mobile clinics.However,while services are generally well received,there are clear opportunities for ameliorating the quality of services provided.For mothers living in remote,deprived areas,outreach is not just an ‘optional extra’ but rather an essential service.

What is known?

·Antenatal care for pregnant women can improve several important maternal,perinatal,and fetal health outcomes.

·The value of quality antenatal care delivered by adequate numbers of well-trained staff for both mothers and their newborns is evident.

What is new?

·Financial issues played a major role in preventing women from seeking antenatal care.

·Mobile clinics that can be moved into the remote areas where services are most needed is a viable way of delivering antenatal care.

·Offering free antenatal care services via mobile clinic is an excellent way of getting to interact with women who are vulnerable and have little contact with anyone outside their own home environment.

1.Introduction

Antenatal care for pregnant women can improve several important maternal,perinatal,and fetal health outcomes.The efficiency of many standard antenatal care practices and a rise in the ratio of pregnant women seeking antenatal care in the last 30 years has improved matters,but there are still high numbers of women who suffer illnesses during pregnancy,and during and after giving birth,even though these health problems could be prevented or treated[1,2].Worldwide,there is an average daily death toll of 810 women who die during pregnancy and childbirth.A good proportion (94%) of these mothers die in countries with low and lowermiddle-income levels,and most of these deaths are preventable[3].According to the most recent Jordanian National Maternal Mortality Report(2019),there were 1451 deaths among women of reproductive age,62 of which were maternal deaths with a specific reported cause of death[4].The major contributor to this death toll is inadequate antenatal care coverage.Many women attend an insufficient number of antenatal care visits and often receive care of poor quality when they are seen by a healthcare provider.Despite the availability of antenatal care services,there are several challenges to providing and accessing care in Jordan.One key challenge is the uneven distribution of healthcare facilities,with many rural and remote areas having limited access to services.Many pregnant women in these areas have to travel long distances to reach a health center,which can be a significant obstacle,especially for women with limited mobility or financial resources [5].Another barrier is the cost of antenatal care services,which can be prohibitive for many women,especially those living in poverty[5].In some cases,women may be required to pay for certain antenatal care services,such as ultrasounds or laboratory tests,which can be beyond their means.This can result in women delaying or forgoing care,which can lead to complications and poor health outcomes for both the mother and the infant.

According to a study by Menaka and her colleagues,mobile health services can be helpful for tracking pregnancy and encouraging more antenatal visits by patients.This type of intervention can effectively refer high-risk pregnancies in remote areas and provide timely recommendations.One significant benefit of mobile clinics is the increased convenience they offer women and their families,as they reduce travel time and distance [6].The study suggests that mobile clinics have the potential to offer obstetric care and consultations to both low-risk and at-risk women in rural areas with limited resources,where specialist care may not always be available.

In addition,cultural and social factors may prevent some women from seeking antenatal care,particularly in conservative communities where women may be reluctant to seek care from male healthcare providers [7].Moreover,in some communities,women may face social stigma or disapproval for seeking antenatal care,particularly from male healthcare providers [8].This can discourage women from seeking care or make it difficult for them to receive care in a timely manner.

Another challenge is the high prevalence of risk factors for poor maternal and child health outcomes in Jordan.These risk factors include high rates of anemia,gestational diabetes,and hypertension,which can lead to complications during pregnancy and childbirth[9].Overall,while antenatal care services are available in Jordan,there are significant challenges to ensuring that all women receive the care they need during pregnancy.

These challenges are an important focus for improving maternal health and lowering healthcare costs.As a result,policymakers and health professionals must devise creative programs that may effectively manage maternal health issues,promote preventative health,and enhance outcomes in underserved regions.Mobile clinics can provide numerous benefits for providing antenatal care in outreach areas,which are often areas that are remote and have limited access to healthcare facilities.One benefit is that mobile clinics can bring essential antenatal care services directly to pregnant women in their communities,making it easier and more convenient for them to access care[10].

Another benefit is that mobile clinics can reach women who might not otherwise have access to antenatal care due to distance,lack of transportation,or financial constraints [11]

Mobile clinics can also help to address other challenges that can limit access to antenatal care,such as cultural or language barriers.For example,mobile clinics can be staffed with healthcare providers who are familiar with the local culture and language,which can help to build trust and improve communication between healthcare providers and patients [10].

Some rural populations in various regions of Jordan receive inadequate medical care,particularly in the areas of sexual and reproductive health [12].When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020,it widened the gap in medical services available,especially for the most vulnerable groups: the poor,those without medical insurance,refugees,and non-Jordanians.By bringing antenatal care directly to these communities,mobile clinics can help to reduce barriers to care,such as transportation costs and limited availability of healthcare providers.

Mobile clinics can also be a cost-effective way to provide antenatal care.Studies have shown that mobile clinics can reduce the cost of antenatal care services for both patients and healthcare providers[11].This can be particularly important for women living in poverty,who may not be able to afford the cost of care at a traditional healthcare facility.

Another benefit of mobile clinics is that they can help to overcome cultural and social barriers that may prevent women from seeking antenatal care.Mobile clinics can be staffed by healthcare providers who are familiar with the local culture and language,which can help to build trust and rapport with patients[5].This can be particularly important for women who may be hesitant to seek care from male healthcare providers.

Providing appropriate antenatal care to pregnant women in impoverished populations is one of the key reproductive health concerns[12].Sending mobile clinics to areas where health services are scarce or non-existent is a viable way of expanding communitybased antenatal care coverage.

However,the experience as perceived by those women obtaining antenatal care through a mobile clinic has rarely been reviewed in Jordan.The literature offers very little qualitative data about how the recipients of the services viewed the whole experience.Qualitative data not only gives a comprehensive,vivid picture of women’s opinions of receiving antenatal care through mobile clinics,its quality,and how health workers deal with them,it also offers us a more thorough understanding of the social norms,habits,and barriers that may limit the capacity of some Jordanian women to attend antenatal care clinics and gain full benefit from their services.We need to explore the reality of life as experienced by our interviewees to fully comprehend why they have difficulty accessing antenatal care services[13,14].This allows for a thorough examination of the interviewees’ individual requirements,as well as the cultural and socioeconomic variables that affected the women’s decision to abstain from receiving antenatal care in favor of waiting until the mobile clinic came to their region.Therefore,the current study seeks to better understand the meanings ascribed by mothers to their experiences of obtaining antenatal care via mobile clinics in Jordan,as well as to add a useful contribution to the currently sparse body of knowledge in this field.

2.Methods

2.1.Research design

For this study,the researchers opted for an interpretive phenomenological research design because it allows the researcher to examine,understand and interpret the mothers’ antenatal care experiences by allowing them to express how they felt about them in their language and their natural setting[15].This research topic has received very little attention,so we need more information and a deeper understanding.As a result,this approach was chosen.

2.2.Sample and setting

A purposive criterion sampling approach was adopted to achieve maximum diversity throughout the sample [16].The women who took part in this study had all received antenatal care during their last pregnancy from a mobile clinic in Jordan.There is no logical basis for sample size in applied qualitative studies,as Malterud and her colleagues have made evident.Instead,a researcher can predict with fair certainty that after thoroughly examining a reasonable number of occurrences of a phenomenon,there will be something to report.This estimation was known as “information power” by Malterud’s team [17].The researchers found that they could create a convincing argument and draw a conclusion after their sample reached 10 participants.

The National Woman’s Health Care Center(NWHCC)is in charge of implementing the mobile clinic activities and providing the necessary technical and logistical support.For this reason,the participants were drawn from the NWHCC’s database.The setting of the interview was determined after the woman’s agreement to participate and based on each participant’s preference,was conducted in either a quiet and comfortable place in NWHCC,such as a conference room,or at the woman’s home.

2.3.Data collection

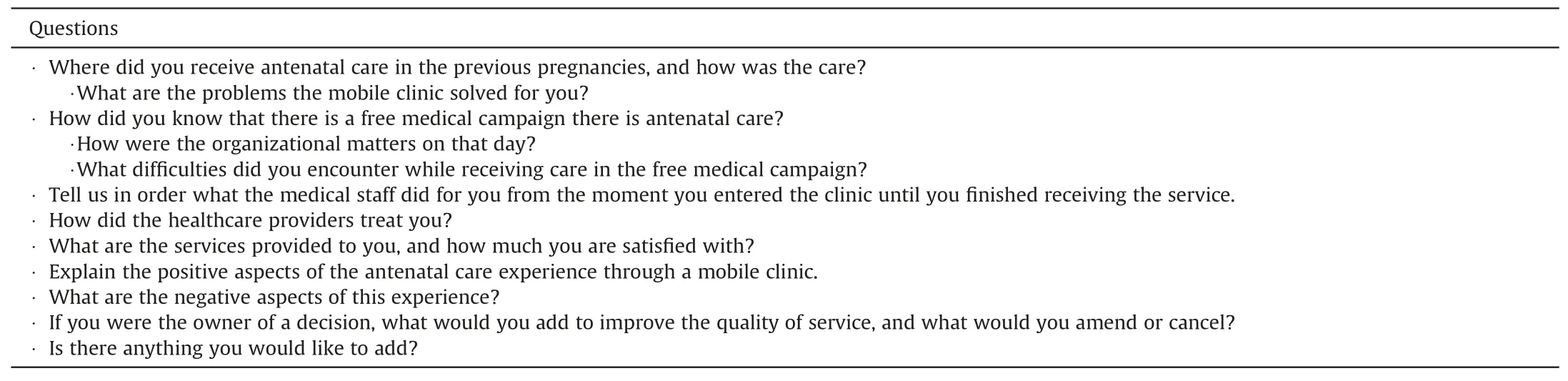

An individual semi-structured interview was chosen in addition to field notes.Each interview was conducted according to a flexible interview guideline,which permitted the researcher to focus on some questions,or add new questions as issues emerged [18].The interview questions emphasized women’s opinions of receiving antenatal care through mobile clinics,the social norms,habits,and barriers that may limit some Jordanian women from attending antenatal care clinics,and how the quality of the service offered to them structured their experience.The interview guideline and probing questions are presented in Table 1.The interview was conducted by the fourth coauthor after she received training on how to conduct a rich interview and build rapport with the participants from the second author,who is an expert in qualitative research.Each interview was conducted once time and ranged from 40 to 50 min and included only the interviewer and the woman.

2.4.Data management and analysis

All interview audiotapes were transcribed verbatim in the researcher’s native Arabic language as soon as possible after each interview [19].Model of interpretive phenomenological analysis and the qualitative data analysis NVivo 9 computer software program were used to organize the data and codes.A Word document containing the interview transcript was imported into NVivo 9 software program,and the researcher initiated the free coding process for the first interview transcript in the English language.When the code is selected,the code exactly represents what the paragraph is talking about.All the previous steps were repeated for all interviews.A new open code was added when new issues emerged.The first author searched for connections between the codes in the initial codes list to cluster them in a more meaningful way.She documented the main ideas to which the codes groups referred.Consistent with interpretive phenomenology,the emerging themes reflect the participants' points of view and how the researcher interpreted them.

Trustworthiness was established by handing the transcripts of all interviews to other researchers to look for other plausible interpretations of the data.The first author's interpretations were also examined by the other researchers,and after taking their recommendations into account,a consensus on the final list of themes was reached.

2.5.Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Jordan/Nursing School.All participants were asked to give their informed consent prior to conducting the interviews,as well as permission to record the interview.Confidentiality,privacy,and anonymity were maintained throughout the study.All participants had an individualized interview.Therefore,participants were not aware of the identities of other participants or who might hear what they said during the interview except the researchers.Rather than using the participants’real names,each one was allocated an identification number(ID)which was the sole form of identification used throughout the study.The researcher and research assistant are the only persons who know the identity of the participants.Moreover,all data is saved in a locked filing cabinet in the researcher’s office.Audiotapes and transcripts of interviews were stored in a password-protected computer and backed up on a password-protected external hard drive.Only the researcher has access to the data.

3.Results

3.1.Personal and obstetric details of the participating women

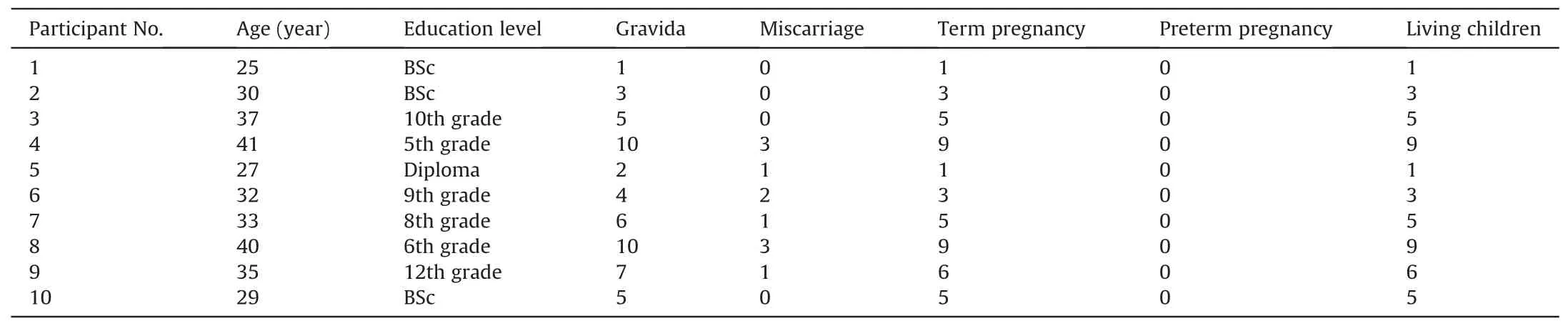

Of the fourteen women who were originally asked to participate in the study,one declined to be interviewed,and three refused to have the interview recorded,leaving a sample of 10 women.

The personal details of the women who received antenatal care experience from the mobile clinic are presented in Table 2.

Table 1 Interview guideline.

Table 2 Personal and obstetric details of the women interviewed for their antenatal care experience via the mobile clinic.

3.2.Themes

3.2.1.Being informed about the medical campaign or missing the opportunity of being informed

The campaign is publicized by all parties participating in thecampaign,such as heads of charitable societies,members of the local community,and on social networking sites.Therefore,one of the ways that the NWHCC used to advertise the date,time,and place of the campaign was to put up posters in charitable societies in the area in which the campaign is to be carried out for members of the community to benefit from the campaign.Unfortunately,some illiterate pregnant women or those who do not regularly visit the societies did not learn that the campaign was taking place.

“I knew through the charitable societies that they issued an advertisement,and many of the neighbors knew.” (P3)

“Charitable societies in the region advertised it.” (P5)

Other women found out about the campaign through their social networks,such as relatives and neighbors.They informed each other,and the news passed from one person to another.

“My sister informed me.” (P1)

“I don’t have a mobile.My neighbor is a teacher,and she told me.”(P4)

“I told my sister and my brother's wife and my husband’s second wife.” (P6)

Social media sites were used to advertise the campaign,using the society’s Facebook page,also via WhatsApp.Some of them said:

“I have Facebook and I saw the advertisement.The neighbors told each other via WhatsApp.” (P10)

“I knew about the campaign through the society’s Facebook page.”(P2)

While most of the women knew about the campaign,some were still uninformed about the event and missed the opportunity to receive antenatal care.In some deprived areas,where women are not allowed to leave the house without the permission of their husbands,they suffer from the negative impact of rigid gender norms and roles.As a result,their freedom and mobility are restricted,as is their contact with the outside world and other women outside their home milieu.

“There are women who did not know about the free medical day,and they needed to be treated.Some women can’t go outside the home without their husbands'permission,and they hadn’t any idea about the campaign.Usually,they get pregnant and deliver without any medical follow-up.” (P6)

Although social media is a good way to advertise,the expectation that everyone has a mobile phone and accounts on social media is not totally accurate.We must consider that some women do not have a mobile phone,even if they represent a small minority.

“My husband is strict,I do not have a phone,and he is the only one who has.” (P4)

The areas where free medical campaigns are held are usually poor remote areas.So,some women have an old phone and not a smartphone,and they can’t create any social media accounts.

“My sister told me because I don’t have Facebook or WhatsApp.My phone is an old type,I can only make necessary calls on it.” (P1)

3.2.2.The experience of receiving antenatal care was wonderful,although there was only one thing lacking

In this topic,women detailed how they benefited from receiving ambulatory health care from the mobile clinic and highlighted the positive aspects of the experience.They summed up by pointing out some shortfalls where improvements could be made.They asserted that if these matters were rectified,the care would be impeccable.

All participants appreciated the organizational matters of the campaign,and despite the high number of patients and distancing measures imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic,there was no crowding or pushing,and everything was organized from the start.

“It was crowded,but there was organization.They distributed gloves,masks,and hand sanitizer,and they guided me where to go.”(P10)

The mobile clinic has become an important part of maternity care for underprivileged women.All the participants appreciated the services provided to them and how much time and money they saved as a result.This free and charitable mobile clinic served to close the gap in healthcare coverage and deliver services tailored to these vulnerable women’s maternity health requirements.Furthermore,financial concerns have been identified as one of the main causes behind the strong likelihood of this group of women failing to receive antenatal care.

“The experience was nice,and it saved us time and money because we received care and medicines for free.” (P9)

“We always wait for the campaign to be treated because we do not have insurance.” (P7)

Usually,many institutions and companies participate in supporting medical campaigns with cash or in-kind donations.Among the in-kind donations that are distributed on medical days are a range of medicines and personal care products needed by the patients.The women praised the bags of feminine supplies that were distributed to them.

“The midwife gave me a bag containing underwear,towels,and sanitary pads.…The beautiful thing was the underwear was made of cotton and of high quality.” (P8)

The majority of the women lack health insurance and are uninformed about any new decisions.Therefore,some women were not aware of the minimal cost insurance for pregnant women,which was generously granted by His Majesty King Abdullah 11 years ago.This insurance,valid for eleven months,requires the woman to pay 50 Jordanian dinars to receive antenatal care and treatment for all pregnancy complications and any possible operations in governmental health centers or hospitals.Uninsured women were introduced to this type of insurance during the campaign.

“In the campaign,I knew about the insurance for pregnant women;they told me to pay 50 dinars to the Ministry of Social Development and that it would cover me until I was delivered.” (P3)

The women explained that the most convenient issue in the care was the availability of a female doctor.It was a critical point in making the decision to attend the campaign or not.Some connected their receiving antenatal care by mobile clinic depended on the doctor’s gender,for reasons related to themselves or their husbands.

“It is very comfortable to have a female doctor.Our men are very strict in their thinking that she was a female doctor who examined us,and I am more comfortable,and I asked her many questions related to my condition.If it had been a male doctor,I would not have asked him.” (P3)

The women spoke about one problem that these campaigns are too infrequent.They occur only once,or sometimes twice,a year,which is not enough,and there is no follow-up of cases by doctors.The participants called for an increase in the number of campaigns,especially for remote and poor areas,because they need this service.They said that if women could receive care every month or two during pregnancy,it would be of great benefit to both the mother and the baby.

“Increase the number of medical campaigns.If it was held every two months,a lot of people would benefit,especially those who don’t have money.We need it urgently;I wish there were 3 days in every area because there are many people.Also,I wish there was a dental clinic,I swear to God,my teeth hurt me,and I can’t go to the clinic because of money.” (P1)

3.2.3.They safeguard our life and take any opportunity to educate us

Many of the women who attended the mobile antenatal clinic had not received any pregnancy check-ups yet or were several months late in their pregnancy follow-up.They believed that,if they do not feel anything abnormal,their conditions must be stable and safe,especially since this situation was a repeat of what happened in their previous pregnancies and nothing bad happened.The concern here is that the main reference for many women in any health complaint is her mother or mother-in-law,and both are a source of confidence for all.These old women in the family,despite their wealth of lived experience,are not well qualified to give any advice,and their knowledge is not sufficient to handle any serious complaints.

“I didn’t have follow-up during my pregnancies,and God protect me,and I have 10 children.Anything that happened to me I asked my mother-in-law,who is the consultant of the family,and my husband trusts her.“(P4)

Some mothers mentioned that some dangerous cases were discovered through their attendance at the antenatal mobile clinic.If these complications had continued undetected and they had not received the appropriate treatment and referral to the hospital,their lives would have been in danger.

“I am the second wife,and there is no birth spacing.My husband wants children.During the campaign,they discovered that I had anemia.My Hb level was 9,and they gave me treatment and followed up with me later.“(P6)

“They found out that the placenta was down in the uterus,and they referred me to the hospital.“(P7)

A good number of women do not follow up in any health center or hospital.In addition,they have a scarcity of medical information.The interviews revealed that the healthcare providers were aware of this point,and they took advantage of the opportunity to meet with the women to educate them about some health issues,each according to their needs.

“They told me about folic acid and that I should take it during the whole pregnancy,I stopped it after the third month.“(P5)

Repeated childbearing without a period of spacing between births is one of the main problems that most mothers suffer from in these remote areas,due to misinformation about contraceptives or lack of health awareness.All caregivers involved are aware of this problem and know that women do not come to receive postnatal care.So,they were keen to provide every mother with appropriate health education.Sometimes,contraceptives are dispensed to women during pregnancy to be used after birth,as the caregivers are sure that they will not be able to meet these mothers after birth.

“I have 10 children and I always give birth and get pregnant straight away.When I came to the campaign,they gave me contraceptive pills and told me that I had to start taking them after forty days of delivery.“(P4)

“They educated us about contraceptives….I was under the impression that birth control pills cause infertility and cancers.They changed all our ideas.” (P9)

4.Discussion

This study presents the perception of Jordanian women who received antenatal care via the mobile clinic.The results of the study showed some positive aspects of the experience which should be promoted.On the other hand,the results revealed challenges and obstacles that prevent these mothers from receiving quality antenatal care.

4.1.Positive aspects of the experience

The mothers expressed their appreciation for the care given to them.They valued that these health services were provided to them in the area where they lived for free.From their point of view,the care was integrated and sensitive to their culture.It included examination by a female doctor,examining them with an ultrasound device,conducting laboratory tests,then giving them appropriate health education according to the needs of each woman,obtaining medicine,and finally praising them a feminine bag containing some necessary supplies that women,in their current economic situation,cannot purchase.From the findings,the in charge of antenatal care campaigns were aware that the gender of the doctor was of great importance.The presence of a female doctor reflected positively on the mothers’desire to receive care.In these campaigns,a female obstetrician must always be provided,because this is a key point in the culture of people in these remote areas.This result supported the findings of several studies that focused on the gender of the doctor [20].

4.2.Challenges and obstacles to receiving quality antenatal care

On contrary to positive aspects of the experience,our results showed a disparity between the real obstetric history of some of the women and what was recorded in the women’s medical files during the campaign.This is in addition to some missing obstetric data that results in the low quality of primary data.Our study further highlights that incorrect documentation puts some women at more serious risks.Their files indicate that they are low-risk pregnancies when they are,in fact,categorized as high-risk.All these lowquality data will prevent women from receiving continuous,timely maternity care.These findings correspond with those of a previous Tanzanian study that revealed the importance of highquality data if decisions are to be made at the clinical,institutional,and policy levels to improve maternity services in resourceconstrained contexts.Accurate patient records are also of the utmost importance for good communication between maternity health team members,continuity of treatment,and the safety of the patient.It is crucial that facilities possess high-quality,actionable primary health data if they are to improve the quality of maternity treatment at the facility level [21].

Also,the results presented that antenatal care was inaccessible for all women and fragmented to the group of women.Due to a number of social,cultural,and organizational determinants,the announcement of the existence of a free medical campaign did not reach all pregnant mothers,which calls for creative thinking to come up with ways to solve this problem.A major obstacle that emerged is the dominance of some men and their decision-making that is related to maternal health.Some women in the study admitted that they are deprived of communicating with the outside world except through their husbands,as some do not have a phone or accounts on social networking sites.Some mothers reported that they could not leave the house unless accompanied by their husbands.Therefore,it is useful to activate home visits in these areas,because we found some women who did not receive any antenatal care,and their first visit was during the medical campaign and at a late stage of pregnancy.The research team has no way of knowing the number of pregnant mothers who did not attend the campaign and did not receive antenatal care in any health institution.Therefore,the best solution in such circumstances is to visit these mothers in their homes after asking people in the local community,such as neighbors.Such lines of inquiry could lead to the discovery of such women and lead to them receiving quality antenatal care at home,if they are unable to visit the antenatal clinic.In this way,we guarantee the continuity of antenatal care.The benefit of home visits for pregnant women has been proven in several studies.Cockcroft et al.(2019)advise applying home visits in settings where pregnant women are physically unable to attend a clinic or hospital for antenatal care,as it reduces maternal risk and improves pregnancy outcomes [22].A Japanese study examined the extent to which home visits to high-risk pregnant women after 28 weeks’gestation improved birth outcomes.They proved its effectiveness in preventing preterm birth and achieving prolonged gestational age[23].In addition to home visit,if we want to solve the problem from its toots,we must empower and strengthen the personality of mothers so that they are able to claim their basic rights.Empowering women in close societies to receive antenatal care can have significant benefits for the health and well-being of both mother and baby.In many close societies,women face social and cultural barriers that prevent them from accessing the care they need during pregnancy.However,when women are empowered to seek out antenatal care,this will improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes and reduce the burden of preventable deaths and disabilities.One of the organizational determinants was the scarcity of medical campaigns in remote areas.This led to fragmentation of care,as they didn’t receive antenatal care services except in the free medical campaign.Therefore,a comprehensive plan should be set in place to ensure the continuity of antenatal care for this group of women.The organizers of these campaigns should increase their frequency in remote areas to ensure that the World Health Organization (WHO) standards for the care of pregnant women are achieved.The 2016 WHO guidelines for antenatal care recommended eight visits as a minimum number of antenatal care contacts,the first contact to occur during the first trimester of pregnancy [22].

On the other hand,the results revealed that the financial factor is one of the main factors that prevent women from receiving antenatal care.It seems that women’s residents in these remote areas were deprived of knowing new decisions related to their health insurance.Some women did not access maternity services because of the bill for care that they could not afford.It is unfair that the Jordanian Ministry of Health seeks to improve the care of pregnant women by approving insurance for pregnant women,while the women who may benefit from this insurance do not know about it.Some pregnant mothers were unaware of the existence of maternal health insurance from the date of conception for a period of 11 months.This insurance,issued by the Jordanian Ministry of Health,covers all medical care throughout this period in exchange for a small one-time payment.Since the low-cost health insurance policy for pregnant women was only introduced 11 years ago,many people are unaware of it.Therefore,officials must disseminate this information among the Jordanian people.It was clear that,for mothers who do not have health insurance and live on very limited incomes,the financial issue played a major role in preventing them from seeking antenatal care.In a study conducted by Fernandes et al.it was evident that more women had begun to use maternal healthcare services since the Ministry of Health had made insurance available to them [23].

A dangerous indicator that emerged from this study was that pregnant women considered old females in the family as a source of information and consultations,and the pregnant women and their husbands trusted them.Bawadi and Al-Hamdan asserted in their study that childbirth is a female issue in Jordan,and old females in the family are a major source of information and advice [24].Therefore,maternity care providers should discuss with expectant mothers and raise their awareness that some serious complications of pregnancy initially have no symptoms.However,if they are detected and diagnosed early,they can be treated and controlled.Rather than listening to the opinions of older women in the family who have no medical training,pregnant women should consult a doctor or other healthcare professional.The doctor is required to conduct laboratory tests and use the ultrasound device for diagnosis,and the doctor is the only trusted authority for consultation.

5.Limitations of the study

One of the study’s limitations is the small sample and the selection of participants from deprived areas.This led to a lack of diversity in the answers and an inability to evaluate the quality of antenatal care provided to them through mobile clinics.All the participants were satisfied with the services offered.They looked at the issue from their own perspective that receiving care in their areas for free,with female health care providers is ideal.This narrow vision and poor experience of antenatal care in other places limited their ability to compare and criticize some aspects of care.Purposive sampling is prone to lack of transparency which can make it difficult for other researchers to replicate the study.However,in this study we seek to know the perceptions of pregnant Jordanian women who received antenatal care via mobile clinic,and how they evaluated the services that were available.Another limitation was that the study was conducted in only one place in Jordan and interpretative phenomenological studies typically have a small sample size,which can limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations.The aim of the study was to understand the meanings ascribed by mothers to their experiences of obtaining antenatal care via mobile clinic in Jordan,as well as to add a useful contribution to the currently sparse body of knowledge in this field,not to generalize the findings.We believe we achieved the aim of the study and these limitations do not necessarily weaken the study.In contrary,we got dense description of the experience that enrich our understandings.

6.Conclusion

Our results disclosed that mobile clinics that can be moved into the remote areas where services are most needed is a viable way of delivering good antenatal care.It is relatively inexpensive and has been found to satisfy the needs of women living in regions where health services are poor.Moreover,offering free antenatal care services via mobile clinic is an excellent way of getting to interact with women who are vulnerable and have little contact with anyone outside their own home environment.It was alarming to learn that many expectant mothers consulted older females in the family if they suffered from any health complaints or problems.Even more concerning is the fact that most women and men trust their opinion and take it for granted.A detailed discussion with mothers and fathers should be conducted to raise their awareness of the seriousness of this matter.Finally,the study emphasized the discontinuity and fragmentation of antenatal care services due to an unsustainable health campaign in a remote area.

7.Implications for nursing and health policy

The study showed that mobile clinics are a viable option for delivering antenatal care to women in remote or underserved areas,particularly in countries with limited resources.Policymakers need to consider investing in mobile clinics to improve access to healthcare for pregnant women.Also,the study highlighted the importance of providing culturally appropriate care to women during pregnancy.Understanding the lived experiences of Jordanian mothers and their specific cultural beliefs and practices may help healthcare providers tailor their care to meet the unique needs of this population.In addition to providing antenatal care services,mobile clinics can also serve as a platform for health education and outreach.Through mobile clinics,healthcare providers can educate pregnant women and their families about healthy pregnancy practices,family planning,and other important health topics.

Funding

This paper funded from National Women's Health Care Center,Jordan.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hala A.Bawadi:Conceptualization,Methodology,Data curation,Writing -review &editing.Asma’a S.Abu Abed:Data Curation,Writing -review &editing.Zaid M.Al-Hamdan:Data Curation,Writing-review&editing.Safa M.Alzubi:Data curation,Writing-original draft,Writing -review&editing.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We would like to sincerely thank all the women who took part in the study.

Appendix A.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2023.03.005.

杂志排行

International Journal of Nursing Sciences的其它文章

- A feasibility study on home-based kyphosis-specific exercises on reducing thoracic hyperkyphosis in older adults

- Development and validation of dynamic nomogram of frailty risk for older patients hospitalized with heart failure

- Validation of the Portuguese version of the social isolation scale with a sample of community-dwelling older adults

- Effects of pre-operative education tailored to information-seeking styles on pre-operative anxiety and depression among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A randomized controlled trial

- Factors influencing the quality of sexual life in the older adults: A scoping review

- Comparison of the effects of three kinds of hand exercises on improving limb function in patients after transradial cardiac catheterization