阿奇霉素:多功能的抗生素药物

2023-04-29赵丽凤袁征李鹰飞

赵丽凤 袁征 李鹰飞

摘要:阿奇霉素是一种在红霉素化学结构基础上修饰而得到的大环内酯类抗生素。作为第二代大环内酯类抗生素,阿奇霉素抗菌谱与红霉素相仿,具有广谱抗菌的特点,但其抗菌活性明显改善。近些年研究发现,除基本的抗菌作用外,阿奇霉素还具有抗炎、调节免疫、抗病毒以及抗疟疾等药理作用,其临床应用范围不断扩大。本文对阿奇霉素的药理作用及相关作用机制进行了综述,以期为其临床应用提供科学指导。

关键词:阿奇霉素;抗菌;抗炎;免疫调节;抗病毒;抗疟

中图分类号:R978.1 文献标志码:A 文章编号:1001-8751(2023)01-0033-06

Azithromycin: A Multifunctional Antibiotic Drug

Zhao Li-feng, Yuan Zheng, Li Ying-fei

(Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing 100700)

Abstract: Azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic obtained by modifying the chemical structure of erythromycin. As a second-generation macrolide antibiotic, azithromycin has a similar antibacterial spectrum to erythromycin, so it has the characteristics of broad-spectrum antibacterial, but its antibacterial activity is significantly improved. In recent years, researchers have found that in addition to the basic antibacterial effect, azithromycin has other pharmacological effects, such as anti-inflammatory, immune regulation, antiviral and antimalarial. Therefore, the scope of clinical application of azithromycin continues to expand. This article reviews the pharmacological effects and mechanism of action of azithromycin for its scientific clinical application.

Key words: azithromycin; antibacterial; anti-inflammatory; immune regulation; antiviral; antimalarial

阿奇霉素是一种半合成的十五元环大环内酯类抗生素,由红霉素A9-酮基产生肟化作用后经贝克曼重排、N-甲基化等一系列反应所得[1]。阿奇霉素于1980年由克罗地亚普利瓦制药公司研制,次年被推出市场[2]。阿奇霉素对革兰阴性细菌、厌氧菌及其他病原体均有很强的活性,尤其对流感嗜血菌具有明显的抑制作用。由于用药安全系数高,阿奇霉素被世界卫生组织列为最安全的药物之一[3],也被列入基本药物清单,并在全球大规模生产[4]。

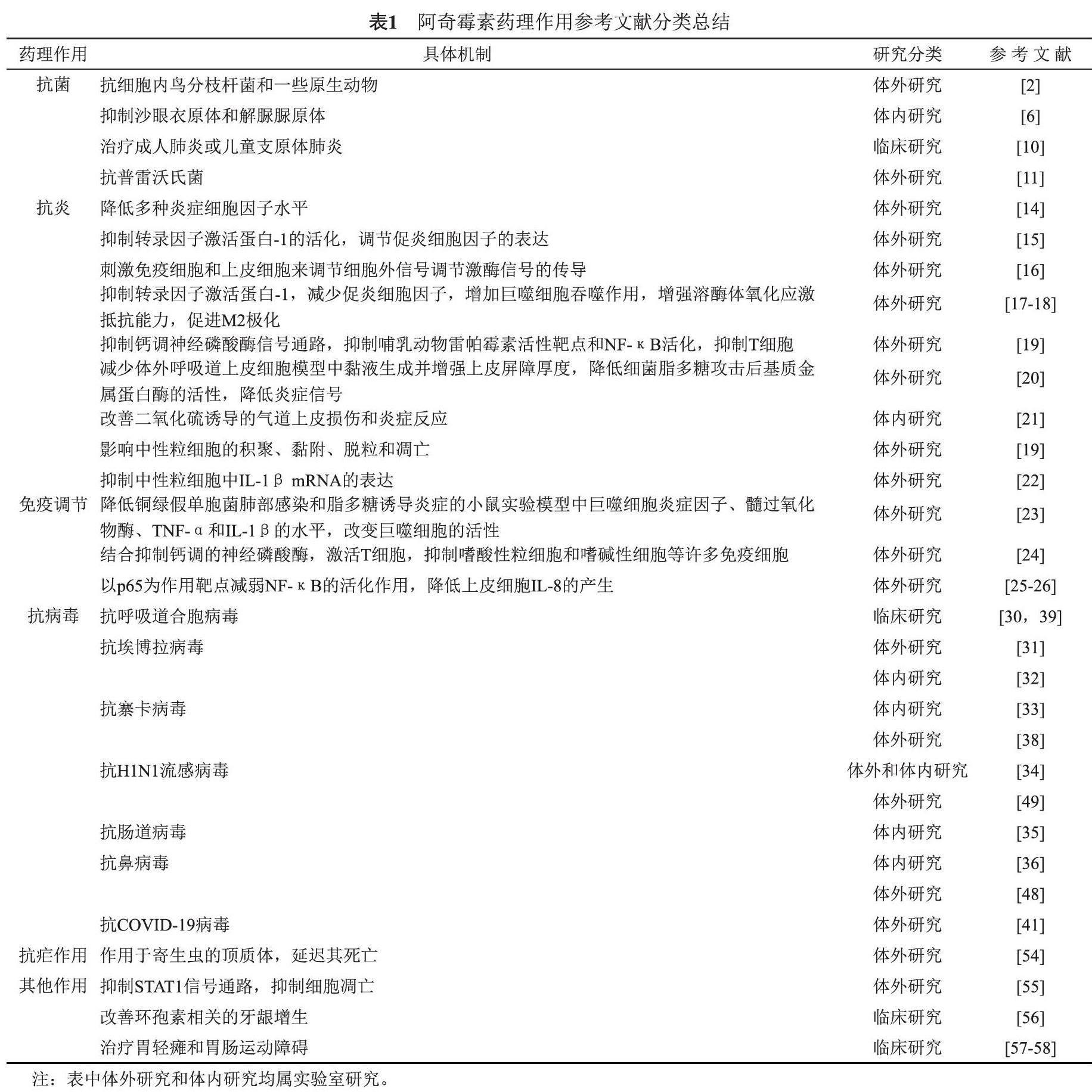

研究表明,作为一种长效抗生素,阿奇霉素不仅具有较好的抗菌活性,还具有抗炎、调节免疫功能、抗病毒、抗疟疾等作用。此外,在近两年肆虐全球的新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)的治疗中,阿奇霉素也表现出较好的抗炎及免疫调节作用。因此,阿奇霉素可能会成为一个老药新用的典型范例。本文查找了近二十年来关于阿奇霉素的相关文献报道,就阿奇霉素的抗菌、抗炎、调节免疫功能、抗病毒、抗疟疾等药理作用进行了综述,按照其药理作用差异将相关文献进行了分类(详见表1),并讨论了其药理作用的分子机制及临床应用,旨在为阿奇霉素的科学研究及临床应用提供指导。

1 抗菌作用

阿奇霉素具有红霉素的重组结构,对革兰阳性菌的活性不如红霉素,但对流感嗜血杆菌、卡他莫拉菌等革兰阴性菌的活性要比红霉素高得多,对大肠埃希菌、沙门菌和志贺菌等肠杆菌目也有活性。此外,阿奇霉素对嗜肺军团菌、伯氏疏螺旋体、肺炎支原体等也有抑制作用。已有研究发现,阿奇霉素比红霉素抗大肠埃希菌、肺炎链球菌的能力至少强5倍,抗流感嗜血杆菌的能力至少强10倍[5]。更有意义的是,阿奇霉素对沙眼衣原体和解脲脲原体的抑制能力比红霉素更强[6]。此外,阿奇霉素对细胞内鸟分枝杆菌和一些原生动物也具有较强活性[2]。

一般来说,阿奇霉素的抗菌机制与红霉素大致相同,即通过可逆地结合敏感微生物的50S核糖体亚基,以阻止新生肽链的翻译与组装,最终抑制依赖细胞中心法则的细菌蛋白质的翻译过程以抑制细菌生长,实现抗菌作用[7-8]。但是,阿奇霉素的酸稳定性强于红霉素,更容易通过胃肠道吸收。同时,阿奇霉素的细胞组织分布更加均匀,并且具有持久的高浓度组织,半衰期可长达40 h,因而抗菌时间较红霉素更长。

在呼吸道感染、口腔厌氧菌感染、皮肤感染、软组织感染及泌尿生殖系统感染等临床疾病的治疗中,阿奇霉素发挥了重要作用。并且,在临床上由于服用阿奇霉素而引起的不良反应发生率相对较低,因此阿奇霉素安全性高,可靠性强,易于患者接受[9]。此外,因具有广泛抗菌谱,阿奇霉素也常用于成人肺炎或儿童支原体肺炎的治疗[10]。另有研究表明,阿奇霉素可以减少普雷沃菌引起的炎症,是普雷沃菌感染的可能治疗药物[11]。

2 抗炎作用

阿奇霉素具有显著的抗炎活性[12-13]。研究表明,阿奇霉素能够降低多种炎症细胞因子的水平,包括白细胞介素(IL)-1β、IL-2、肿瘤坏死因子(TNF)和粒细胞—巨噬细胞集落刺激因子(GM-CSF)等[14]。阿奇霉素也被认为能够抑制IL-6和IL-12,并促进活化的小鼠巨噬细胞产生IL-10。有证据表明,这些抗炎作用是通过抑制核因子-κB(NF-κB)的激活来实现的。此外,阿奇霉素还可以抑制转录因子激活蛋白-1(AP-1)的活化,而这些激活因子能够调节IL-8、IL-6、TNF-α和IL-1β等促炎细胞因子的表达[15]。因此,阿奇霉素降低IL-8产生也可能是通过其抑制丝裂原活化蛋白激酶和细胞外调节激酶。

阿奇霉素的抗炎作用主要表现在免疫细胞和上皮细胞中。一些研究发现,阿奇霉素对免疫细胞和上皮细胞具有刺激作用,并通过刺激中性粒细胞脱粒和吞噬作用相关的氧化暴发来调节细胞外信号调节激酶1/2(ERK1/2)信号传导[16]。这些初始刺激作用之后,AP-1、NF-κB、炎症细胞因子和黏蛋白得到释放,从而发挥阿奇霉素整体的抗炎作用。在巨噬细胞中,阿奇霉素通过抑制AP-1靶点来减少脂多糖诱导的促炎细胞因子,增加细胞吞噬作用,实现溶酶体对氧化应激抵抗能力的增强以及巨噬细胞M2极化的促进[17-18]。阿奇霉素还可以通过抑制钙调神经磷酸酶信号通路、哺乳动物雷帕霉素活性靶点和NF-κB活化来抑制T细胞[19]。此外,在体外呼吸道上皮细胞模型中,阿奇霉素能够减少黏液生成并增强上皮屏障厚度,还可以降低细菌脂多糖攻击后基质金属蛋白酶(MMP)的活性,从而降低炎症信号,这有助于保持细胞的完整性和上皮屏障的功能性[20]。已有研究证实,阿奇霉素可以改善二氧化硫诱导的气道上皮损伤和炎症反应[21]。

阿奇霉素以粒细胞为靶点具有一定程度的特异性,富集于粒细胞溶酶体中,影响中性粒细胞的积聚、黏附、脱粒和凋亡[19]。Gibson等[22]的体外研究证实,8 μg/mL浓度的阿奇霉素可以持续抑制中性粒细胞中IL-1β mRNA的表达。阿奇霉素易集中于中性粒细胞浸润增加的感染和炎症部位,可能与中性粒细胞摄取阿奇霉素和其在感染部位释放缓慢有关,延长了其作用时间。此外,阿奇霉素通过影响黏附蛋白的表达、降低趋化性和氧化暴发来调节多形核中性白细胞的功能。因此,阿奇霉素通过多种机制抑制中性粒细胞对细胞因子和趋化因子基因的表达。

3 免疫调节作用

阿奇霉素具有多种免疫调节作用,其免疫调节作用与抗炎作用是密切联系的。在铜绿假单胞菌肺部感染和脂多糖诱导炎症的小鼠实验模型中,阿奇霉素能够明显降低巨噬细胞炎症因子、髓过氧化物酶、TNF-α和IL-1β的水平,进而改变巨噬细胞的活性[23]。

以阿奇霉素为代表的大环内酯进行免疫调节的主要途径包括:大环内酯与抑制钙调的神经磷酸酶结合,从而激活T细胞,随后嗜酸性粒细胞和嗜碱性细胞等许多免疫细胞被抑制[24]。此外,阿奇霉素能够以p65为作用靶点减弱其下游成分肺上皮细胞NF-κB的活化作用,从而降低上皮细胞IL-8的产生[25-27]。另外,在哺乳动物细胞中,阿奇霉素能够以细胞内丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(MAPK)为靶点,影响ERK1/2和ERK下游的NF-κB通路。ERK1/2和NF-κB通路涉及炎症细胞因子表达、细胞增殖和黏蛋白分泌等细胞功能,因而阿奇霉素的免疫调节功能可通过此通路进行解释。值得关注的是,COVID-19对人体免疫系统的影响也与ERK1/2和NF-κB通路有关,因此阿奇霉素在COVID-19患者中的免疫调节作用也可用此机理进行解释[28]。

由于具有免疫调节作用,阿奇霉素可以有效治疗囊性纤维化(CF)、非CF型支气管扩张、慢性阻塞性肺病、慢性鼻窦炎、败血症和弥漫性全细支气管炎等多种慢性肺部疾病[29]。

4 抗病毒作用

阿奇霉素具有抗病毒特性,可以与其他抗病毒药物协同工作。大量病毒临床用药和科学实验证实了阿奇霉素的抗病毒活性,这些病毒种类包括呼吸道合胞病毒[30]、埃博拉病毒[31-32]、寨卡病毒[33]、H1N1流感病毒[34]、肠道病毒[35]和鼻病毒[36]。体外抗病毒活性研究显示,除H1N1流感病毒外,阿奇霉素对上述病毒的50%抑制浓度范围为1~6 μmol/L[37]。在治疗寨卡病毒的2 177种药物筛选实验中,阿奇霉素被证实能够减少神经胶质细胞系和人类星形胶质细胞中的病毒增殖和病毒诱导所致的细胞病变效应[38]。此外,阿奇霉素对呼吸道合胞病毒的抑制活性在婴儿的随机研究中亦得到了证实[39]。另外,阿奇霉素对埃博拉病毒的有效预防也在小动物模型实验中得以验证[32]。更具有现实意义的是,阿奇霉素抑制COVID-19病毒活性,且能够与其他药物协同抵抗COVID-19病毒循环[40]。Andreani等[41]报道了阿奇霉素单独用药也具有显著抗COVID-19病毒的作用。

阿奇霉素抵抗不同病毒的具体作用机制不同。阿奇霉素能减少病毒进入细胞,并通过多种作用增强机体对病毒的免疫应答[34,42]。数据表明,阿奇霉素具有诱导模式识别受体、干扰素(IFN)和IFN刺激基因的能力以使病毒复制减少。阿奇霉素还能够直接作用于支气管上皮细胞,维持其功能,以减少黏液分泌,促进肺功能[28]。在病毒感染的宿主细胞中,阿奇霉素诱导细胞内抗病毒基因的mRNA和IFN刺激基因的表达,最终通过增加IFN通路介导的抗病毒反应实现抗病毒功能[43]。阿奇霉素还可通过上调I型、Ⅲ型干扰素(尤其是干扰素-β和干扰素-λ)[44-45]、病毒识别的基因如MDA5和RIG-I的表达实现抗病毒功能[46-47]。阿奇霉素可以减少原代人支气管上皮细胞体外感染期间鼻病毒的复制和释放,这一发现也在囊性纤维化患者中得到证实,阿奇霉素再次治疗可使病毒脱落大幅减少[48]。最近的研究数据也显示阿奇霉素可以使A549细胞中的H1N1病毒复制减少,半抑制浓度(IC50值)为68 μmol/L[34,49]。阿奇霉素可以有效地抑制寨卡病毒感染,在病毒感染后期,阿奇霉素还能上调I型和Ⅲ型的IFNs及其下游ISGs表达。阿奇霉素还能诱导抗病毒模式识别受体(PRRs)MDA5和RIG-1的表达并提升TBK1和IRF3的磷酸化水平实现抗病毒作用[44]。

值得注意的是,因其有抗COVID-19病毒的作用[40-41],阿奇霉素在临床上曾被纳为治疗COVID-19的处方之一,但经Molina等[50]和Hraiech等[51]研究,发现阿奇霉素单独以及联合用药并未展现出降低死亡率或消除病毒方面的作用,因而阿奇霉素仅适用于与该疾病相关的细菌合并感染的治疗,世界卫生组织不再建议在新冠肺炎的治疗中使用阿奇霉素[52-53]。因此,阿奇霉素对于新冠肺炎的有效性有待深入研究。

5 抗疟作用

阿奇霉素联合青蒿琥酯或奎宁应用对疟疾有效。阿奇霉素—青蒿琥酯和阿奇霉素—奎宁是治疗无并发症恶性疟疾安全有效的联合途径,值得在特殊患者人群中进一步研究。Dahl等[54]也通过实验证明了阿奇霉素的抗疟作用,发现阿奇霉素可以作用于寄生虫的顶质体,延迟其死亡,但其确切机制有待研究。

6 其他作用

阿奇霉素具有抑制细胞凋亡的功能。有学者将阿奇霉素作用于高糖诱导的足细胞,发现细胞凋亡明显减少,这可能与阿奇霉素能够通过抑制STAT1信号通路抑制细胞凋亡有关[55]。此外,阿奇霉素还具有某些抗感染功效,可能对迟发性哮喘有效。另外,在早期给药时,阿奇霉素可改善环孢素相关的牙龈增生[56]。目前研究发现,阿奇霉素在治疗胃轻瘫和胃肠运动障碍方面也具有广阔的应用前景[57-58]。

7 结语

因其多种药理作用,阿奇霉素的临床应用越来越广泛。但阿奇霉素作为一种抗生素药物,其耐药性仍然是一个世界范围内的健康问题,可能导致阿奇霉素治疗失败。据估计,12%使用1 g阿奇霉素治疗的感染患者在治疗后会产生大环内酯耐药。因此,亟需有更多阿奇霉素耐药性的相关研究,以对阿奇霉素耐药性的发展进行监测,从而建立阿奇霉素耐药性的分子机制,使其发挥更安全、更有效的临床作用。此外,阿奇霉素虽然被世界卫生组织列为最安全的药物之一,但在实际应用中仍然具有厌食、消化不良、胀气、头晕、头痛等潜在的副作用,因此在临床应用中,开具阿奇霉素处方时需加以谨慎,以使其更好地发挥临床价值。

参 考 文 献

Kirst H A. Recent progress in the chemical synthesis of antibiotics[M]. Springer-Verlag, 1990:44-45.

Bakheit A H, Al-Hadiya B M, Abd-Elgalil A A. Azithromycin[J]. Profiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol, 2014, 39:21-40.

World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines: 21st List[Z]. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2019, 7:10.

Laopaiboon M, Panpanich R, Swa Mya K. Azithromycin for acute lower respiratory tract infections[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015, (3):CD001954.

吴超男, 陈娜娜, 李玉琴. 阿奇霉素研究进展[J]. 泰山医学院学报, 2016, 37(11): 1317-1320.

Kuehne J J, Yu A L, Holland G N, et al. Corneal pharmacokinetics of topically applied azithromycin and clarithromycin[J]. Am J Ophthalmol, 2004, 138(4): 547-553.

Shi J, Liu Y, Zhang Y, et al. PA5470 counteracts antimicrobial effect of azithromycin by releasing stalled ribosome in Pseudomonas aeruginosa [J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2018, 62(2): 1867-1877.

Lin L, Lu L, Cao W, et al. Hypothesis for potential pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection—a review of immune changes in patients with viral pneumonia[J]. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2020, (9): 727-732.

纪慧. 阿奇霉素的药理作用和临床应用研究[J]. 中国现代药物应用, 2019, 13(01): 129-131.

林银英, 黄灿坤, 李莉. 阿奇霉素药理作用和临床应用效果研究[J]. 海峡药学, 2019, 31(06): 219-220

Choi E Y, Jin J Y, Choi J I, et al. Effect of azithromycin on Prevotella intermedia lipopolysaccharide-induced production of interleukin-6 in murine macrophages[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2014, (729): 10-16.

Jaffé A, Bush A. Anti-inflammatory effects of macrolides in lung disease[J]. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2001, (31): 464-473 .

Gibson P G, Yang I A, Upham J W, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2017, 390(10095): 659-668.

Cigana C, Assael B M, Melotti P. Azithromycin selectively reduces tumor necrosis factor alpha levels in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2007, 51(3): 975-981.

Desaki M, Takizawa H, Ohtoshi T, et al.Erythromycin suppresses nuclear factor-kappa B and activator protein-1 activation in human bronchial epithelial cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res, 2000, (267): 124-128

Ishimoto H, Mukae H, Sakamoto N, et al. Different effects of telithromycin on MUC5AC production induced by human neutrophil peptide-1 or lipopolysaccharide in NCI-H292 cells compared with azithromycin and clarithromycin[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2009, 63(1): 109-114.

Hodge S, Hodge G, Jersmann H, et al. Azithromycin improves macrophage phagocytic function and expression of mannose receptor in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008, 178(2): 139-148.

Hodge S, Hodge G, Brozyna S, et al. Azithromycin increases phagocytosis of apoptotic bronchial epithelial cells by alveolar macrophages[J]. Eur Respir J, 2006, 28(3): 486-495.

Oliver M E, Hinks T S C. Azithromycin in viral infections[J]. Rev Med Virol, 2021, 31(2): 2163.

Nuji?c K, Banjanac M, Muni?c V, et al. Impairment of lysosomal functions by azithromycin and chloroquine contributes to anti-inflammatory phenotype[J]. Cell Immunol, 2012, 279 (1):78-86.

Joelsson J P, Kricker J A, Arason A J, et al. Azithromycin ameliorates sulfur dioxide-induced airway epithelial damage and inflammatory responses[J]. Respir Res, 2020, 21(1): 233.

Gibson M P, Walters J D. Inhibition of neutrophil inflammatory mediator expressiony bazithromycin[J]. Clin Oral Investig, 2020, 24(12): 4493-4500.

Parnham M J, Haber V E, Giamarellos-Bourboulis E J, et al. Azithromycin: mechanisms of action and their relevance for clinical applications[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2014, (143): 225-245.

Rolfe F G, Valentine J E, Sewell W A. Cyclosporin A and FK506 reduce interleukin-5 mRNA abundance by inhibiting gene transcription[J]. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 1997, 17(2): 243-250.

Lendermon E A, Coon T A, Bednash J S, et al. Azithromycin decreases NALP3 mRNA stability in monocytes to limit inflammasome-dependent inflammation[J]. Respir Res, 2017, 18(1): 131.

Yamauchi K, Shibata Y, Kimura T, et al. Azithromycin suppresses interleukin-12p40 expression in lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma stimulated macrophages[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2009, 5(7): 667-678.

Desaki M, Okazaki H, Sunazuka T, et al. Molecular mechanisms of anti-inflammatory action of erythromycin in human bronchial epithelial cells: possible role in the signaling pathway that regulates nuclear factor-κB activation[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2004, 48(5): 1581-1585.

Kanoh S, Rubin B K. Mechanisms of action and clinical application of macrolides as immunomodulatory medications[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2010, 23(3): 590-615.

Cramer C L, Patterson A, Alchakaki A, et al. Immunomodulatory indications of azithromycin in respiratory disease: a concise review for the clinician[J]. Postgrad Med, 2017, 129(5): 493-499.

Srinivasan M, Bacharier L B, Goss C W, et al. The azithromycin to prevent wheezing following severe RSV bronchiolitis-Ⅱ clinical trial: rationale, study design, methods, and characteristics of study population[J]. Contemp Clin Trials Commun, 2021, 22: 100798.

Du X, Zuo X, Meng F, et al. Combinatorial screening of a panel of FDA-approved drugs identi es several candidates with anti-Ebola activities[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2020, 522: 862-868.

Madrid P B, Panchal R G, Warren T K, et al. Evaluation of ebola virus inhibitors for drug repurposing[J]. ACS Infect Dis, 2015, 1(7): 317-326.

Wu Y H, Tseng C K, Lin C K, et al. ICR suckling mouse model of Zika virus infection for disease mode- ling and drug validation[J]. PLoS Neglected Trop Dis, 2018, 12: 6848.

Tran D H, Sugamata R, Hirose T, et al. Azithromycin, a 15-membered macrolide antibi- otic, inhibits in uenza (H1N1)pdm09 virus infection by inter- fering with virus internalization process[J]. J Antibiot, 2019, 72: 759-768.

Zeng S, Meng X, Huang Q, et al. Spiramycin and azithromycin, safe for administration to children, exert antiviral activity against enterovirus A71 In vitro and in vivo[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2019, 53: 362-369.

Mosquera RA, De Jesus-Rojas W, Stark JM, et al. Role of prophylactic azithromycin to reduce air- way in ammation and mortality in a RSV mouse infection model[J]. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2018, 53: 567-574.

Damle B, Vourvahis M, Wang E, et al. Clinical pharmacology perspectives on the antiviral activity of azithromycin and use in COVID-19[J]. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2020, 108(2): 201-211.

Retallack H, Di Lullo E, Arias C, et al. Zika virus cell tropism in the developing human brain and inhibition by azithromycin[J]. Proc Natl Acad, 2016, 113(50): 14408-14413.

Beigelman A, Isaacson-Schmid M, Sajol G, et al. Randomized trial to evaluate azithromycins effects on serum and upper airway IL-8 levels and recurrent wheezing in infants with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2015, 135: 1171-1178.

Echeverría-Esnal D, Martin-Ontiyuelo C, Navarrete-Rouco M E, et al. Azithromycin in the treatment of COVID-19: a review[J]. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther, 2021,19 (2): 147-163.

Andreani J, Le Bideau M, Duflot I, et al. In vitro testing of combined hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin on SARS-CoV-2 shows synergistic effect[J]. Microb Pathog, 2020, 145: 104228.

Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2020, 71(15): 732-739.

Cure M C, Kucuk A, Cure E. Colchicine may not be effective in COVID-19 infection; it may even be harmful[J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2020, 39 (7): 2101-2102.

Li C, Zu S, Deng Y Q, et al. Azithromycin protects against zika virus infection by upregulating virus-induced type I and Ⅲ interferon responses[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2019, 63(12): 394-419.

Menzel M, Akbarshahi H, Bjermer L, et al. Azithromycin induces anti-viral effects in cultured bronchial epithelial cells from COPD patients[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 28698.

Gautret P, Lagier J C, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2020, 56(1): 105949.

Sch?gler A, Kopf B S, Edwards M R, et al. Novel antiviral properties of azithromycin in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells[J]. Eur Respir J, 2015, 45: 428-439.

Gielen V, Johnston S L, Edwards M R. Azithromycin induces anti-viral responses in bronchial epithelial cells[J]. Eur Respir J, 2010, 36(3): 646-654.

Du X, Zuo X, Meng F, et al. Direct inhibitory effect on viral entry of influenza A and SARS-CoV-2 viruses by azithromycin[J]. Cell Prolif, 2021, 54 (1): 12953.

Molina J M, Delaugerre C, Le Goff J, et al. No evidence of rapid antiviral clearance or clinical benefit with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with severe COVID-19 infection[J]. Med Mal Infect, 2020, 50(4): 384.

Hraiech S, Bourenne J, Kuteifan K, et al. Lack of viral clearance by the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin or lopinavir and ritonavir in SARS-CoV-2-related acute respiratory distress syndrome[J]. Ann Intensive Care, 2020,10(1):63.

Rosenberg E S, Dufort E M, Udo T, et al. Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York State[J]. JAMA, 2020, 323: 2493-2502.

Kim D, Lee J Y, Yang J S, et al. The architecture of SARS-CoV-2 transcriptome[J]. Cell, 2020, 181: 914-921.

Dahl E L, Rosenthal P J. Multiple antibiotics exert delayed effects against the plasmodium falciparum apicoplast[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2007, 51: 3485-3490.

Xing Y W, Liu K Z. Azithromycin inhibited oxidative stress and apoptosis of high glucose-induced podocytes by inhibiting STAT1 pathway[J]. Drug Dev Res, 2021, 82(7): 990-998.

Gomez E, Sanchez-Nunez M, Sanchez J E, et al. Treatment of cyclosporin-induced gingival hyperplasia with azithromycin[J]. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 1997, 12 (12): 2694-2697.

Chini P, Toskes P P, Waseem S, et al. Mcdonald, B. moshiree, effect of azithromycin on small bowel motility in patients with gastrointestinal dysmotility[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2012, 47(4): 422-427.

Moshiree B, Mcdonald R, Hou W, et al. Comparison of the effect of azithromycin versus erythromycin on antroduodenal pressure profiles of patients with chronic functional gastrointestinal pain and gastroparesis[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2010, 55 (3): 675-683.