再次遇上“红”:“梦”又重现了

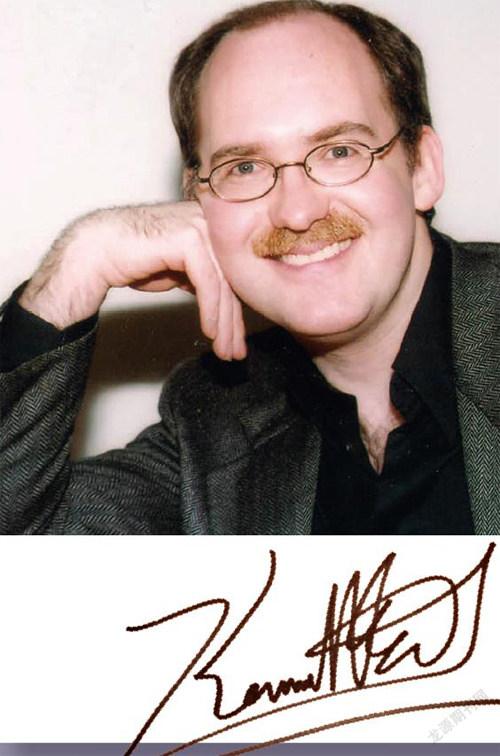

2022-08-07司马勤(KenSmith)

司马勤(Ken Smith)

早在2016 年,当歌剧《红楼梦》在旧金山歌剧院世界首演的时候,我以为自己已经做好了看这部剧所需的一切准备:我阅读了两个不同的英译全本,还有一个厚厚的删节版(966 页);也看过了两部不同的邵氏电影,还有1980 年代末中央电视台制作的电视剧全集,以及2010 年新版《红楼梦》电视剧(我已经尽我所能地坚持下去,但最终还是可惜“弃坑”了)。

但是,当年我没做到的一件事,也是界定普通读者与“红迷”的标准:我没有时间把任何一个版本的《红楼梦》重读或重温一遍。最近我开始步入“红迷”的世界了。

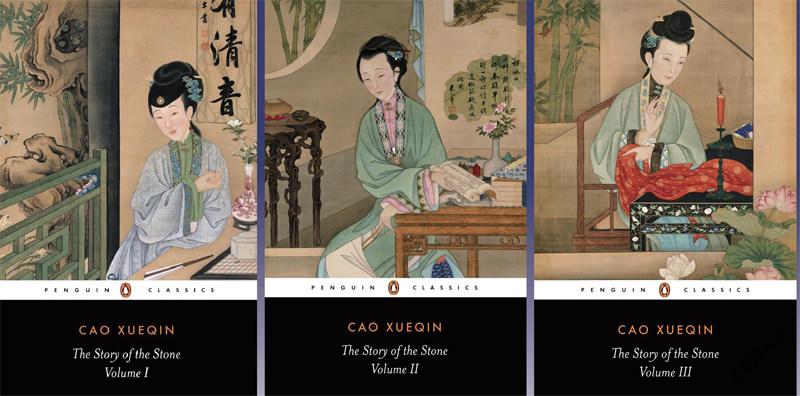

适逢盛宗亮与黄哲伦一起创作的歌剧红楼梦即将重返旧金山——这也是旧金山歌剧院首次在战争纪念歌剧院舞台上重演自家委约作品——我再次翻开霍克思(David Hawkes)与闵福德(JohnMinford)合译的《红楼梦》。这个译本是歌剧剧本的模范,也是这部巨著最权威的英文参考资料。你只需翻翻前十页就能领略到这个英译本独占鳌头的原因。从霍克思- 闵福德译本转移视线至戴乃迭(Gladys Yang)- 杨宪益的译本,反差就像从歌剧舞台跳进邵氏电影一样。我发现,翻译的过程加入了改编的思维——译者时不时会担任编辑的工作,包括取舍不同材料,或是决定哪些地方需要添加背景资料。因为这部小说原著从早期的手稿至印刷的历史极为繁复,许多中文原文的解读已经备受争议,更何况要把《红楼梦》放在另一个语境与文化背景中。

我最近察觉,反过来看,这种错位同样令人伤脑筋。不久之前,我请朋友在家吃休闲午餐,刚从英国大学毕业的香港朋友栩彤翻开我正在阅读的《红楼梦》霍克思- 闵福德译本(五卷之二),写意的午餐时间顿时变成公开的阅读大师班。栩彤只看过《红楼梦》的中文原版,面对某些英文翻译的辞藻就摸不着头脑,尤其是原著中曹雪芹笔下描述清代人物的措辞,译本里显然添上了不少现代英国式的文采。最后,她决定用标准的英式口音朗诵文本。贾宝玉的那些话顿时变得很不一样:听起来好像是奥斯卡· 王尔德(Oscar Wilde)在讲演。

可是,有一件事她觉得很正常,那就是拾起经典再重读几遍。

通常情况下,我并不推崇“重读”。我从前在《金融时报》(Financial Times )的同事拉胡尔· 雅各布(Rahul Jacob)是一位患有强迫症的重读者。在他发表的一篇关于自己与朋友午餐聚会的文章里,充分分析了一对夫妇的这种进退两难的困境:世界上有这么多值得阅读的书籍,但大家的时间和精力有限,所以妻子坚持说:“你有什么理由,来证明再去花时间重读书籍的必要性呢?”她的丈夫则采取了相反的立场:“我们可以重听无数遍唱片,为何不能重读书籍呢?”

在这件事情上,解答问题的首席权威——无论是栩彤或是拉胡尔都会听从这位名人的忠告——应该是弗拉基米尔· 纳博科夫(Vladimir Nabokov)。他曾这样写道:“奇怪的是,一个人不能‘看书,书本只可以重读。”他所指的不单是(如拉胡尔所赞扬的那样)一种重新评估文学的方法,而是致力挖掘藏在文字里深层次内涵的唯一方法。

在来自不同背景的中国朋友中,有数十位曾告诉过我,他们有重读《红楼梦》的习惯(有些人至少每年读一遍,其他人则是在时间允许的条件下重读)。乐评家李澄与作曲家盛宗亮两人首次阅读这部小说时是十来岁,只不过年轻的他们并没有耐心钻研小说里的诗词歌赋。李澄喜欢整部小说的叙事架构,而盛宗亮阅读《红楼梦》时的年龄与贾宝玉相若,则更向往宝玉身边的众多美女。

我接触《红楼梦》时的年龄,要比李、盛二人大得多,但因为面对多重截稿期限的压力,也没有足够时间咀嚼那些诗歌。然而又因为中国文化不是我的母语文化,我也许比其他人更有耐性细读那些关于丰盛宴会的描述,细品贾家那些行酒令的游戏规则。小说中花了很多篇幅描述各种人与物,却没有推进情节。但其实这就是关键:当我重读小说时,我发现字里行间很多看似与剧情无关的描述,原来都是作者埋下的伏笔。

我首次阅读《红楼梦》时,最令我感到好奇的,是那些涉及诗词中丰富的美学以及对格律行文的详尽论述。耐心看罢这堆文字后,才能再次投入故事剧情。直到后来,我才意识到,尽管章节中谈论的主题是文学诗词,但其实呈现的是小说中人物的自身状态。一开始,看到豪门大户有足够的财力供养自家的戏班,我深感仰慕;后来看到家道衰落以至戏班也解散的这段,我同样也被逗乐了。今天大家都有句口头禅:“这是有钱人才会有的问题。”回想起来,因为财务上的轻率行为让贾家无法超脱的那句谚语“另外半杯水”,才最终导致了整个家族的恶性循环,最终一败涂地。

每当一个故事有机会“重生”,无论是用新的语种或是新的媒介,关键的问题是,新版本可以令作品升值吗?虽然具有一些奇怪之处和独有特质,霍克思-闵福德的《红楼梦》譯本,本着原著史诗般的叙事方针,让广大的非华裔读者有机会认识中国文化。但是对于歌剧来说,作品与观众的关系就没有那么公平。

歌剧艺术最本质的原则是将东西简化,因而主要运用的手法应该是“减法”——在处理《红楼梦》这个特别个案时,歌剧的编剧最起码删掉了原著中的380 个角色,还有大部分的叙事线索,以及任何没有直接推动故事主线的段落。因此,歌剧剧本是花了很少篇幅去叙述家族纠葛、行酒令或诗歌会。考虑到歌剧是用英语演唱,汉语中的咬文嚼字也用不上。从任何客观角度来看,歌剧艺术好像没什么可以为《红楼梦》原著添砖加瓦的。

反过来看,《红楼梦》小说为歌剧带来了什么呢?这是一个完全不同的命题。故事里的角色感情极具张力,更有不少人仙逝,原本显赫的家族最后破产,众人颠沛流离,如此适合歌剧表达的坎坷的悲剧情节在世界文学中都很少见。除此之外,剧中那些主要角色跟国际标准歌剧中常设的戏剧与声部特征也十分吻合。

冲动的宝玉当然是个男高音(联想一下卡拉夫);具有天赋但身体孱弱的黛玉是女高音,她体弱多病却敢作敢为,可以比肩咪咪与薇奥莱塔;务实而可靠的宝钗——没有人会感到惊讶——是一位女中音。贾家的其他角色同样符合西方歌剧的模式。从架构上来说,歌剧剧本充分证明,当你把故事的细枝末节去掉(并重新编排或浓缩其他细节),《红楼梦》的感情主轴与很多保留歌剧剧目都很相似。中国与世界分享了很多故事,但极少有像《红楼梦》那般,齐全地符合歌剧艺术所需的全部选项。

《紅楼梦》可以进入歌剧界保留剧目名单吗?现在言之过早,还需看看其他导演与歌剧院搬演这部作品时的处理手法。但是,在旧金山重演赖声川执导的世界首演制作已经是往那方向迈进了一大步。6 月19 日的演出还安排了全球网上直播,观众们还可以在歌剧院官网点播视频(48 小时期限)。不少新面孔将参与此次重演,包括出生于四川女高音张玫瑰饰演黛玉,现居广州的女中音吴虹霓(饰演宝钗),韩国男高音金健雨(Konu Kim,饰演宝玉),以及新加坡指挥家洪毅全(Darrell Ang),他们都将首次亮相旧金山歌剧院。

我终于从我的“梦”里醒过来了。让我雀跃地告诉你,细读霍克思- 闵福德译本第二遍,让我更深入地了解了这部小说,对于人物与他们的环境也产生了新的见解(在已经了解故事发展走向的背景下,对于行文中一早埋下的蛛丝马迹就更加敏锐)。现在,是时候让我们给予盛宗亮- 黄哲伦以同样的礼遇了。

Back in 2016, when Dream of the Red Chamber hadits world premiere at San Francisco Opera, I thoughtId done everything possible to prepare. Id read twodifferent translations of the full novel and a 960-page“abridgement” as well as screening two different ShawBrothers films, the entire CCTV television series from the1980s and as much of the 2010 series as I could stand.

What I hadnt done, though, was the one thing thatmarks the end of being a casual reader and the firstsign of becoming a Red Chamber obsessive: I hadntread the same version twice.

With Bright Sheng and David Henry Hwangsopera about to return to San Francisco—the first ofthe companys commissions ever to be revived athome—I began rereading the full translation by DavidHawkes and John Minford, which was the version thatmost shaped the operas libretto and pretty muchevery major reference in the English language. It tookonly about 10 pages to realize how different this wasfrom merely sampling different versions of the story.Pivoting from Hawkes-Minford to the translationby Gladys Yang and her husband Yang Xianyi isas different as turning from the opera to a ShawBrothers film. Each individual translation, Id becomeaware, is itself an adaptation, a continuous editorialprocess of what to include, what to leave out, whatto contextualize. With the novels convoluted historythrough early manuscripts and controversial printededitions, getting to the actual story is hard enough inChinese, let alone another language or culture.

The dislocation, I recently observed, can be equallyvexing from the opposite direction. Not long ago Iwas hosting a casual lunch when my friend Hilary,a highly literate Hong Kong girl recently graduatedfrom university in the UK, picked up the secondvolume of the Hawkes-Minford edition and cooptedthe occasion into a public reading. Having onlyencountered the story in Chinese, she was oftenpuzzled by specific choices in interpretation, andparticularly amused by a vivid syntax that oftenhas Cao Xueqins Qing dynasty denizens soundingvaguely like modern English subjects. She soonbegan reading with a British accent. Rarely has JiaBaoyu sounded so much like Oscar Wilde.

But the one thing she found perfectly normal wasthe urge to read the book again.

Normally Im not much of a re-reader. Rahul Jacobmy former colleague at the Financial Times and anobsessive re-reader, once wrote about a luncheonof his own where a married couple illustrated thedilemma completely. With so much to read and solittle time, the wife maintained, how can you justifyreading a book again? Her husband took the oppositestand: we have no problem listening over and over tothe same recordings, so why not return to books?

The main authority in this matter—and probablythe one figure to whom Hilary and Rahul wouldboth defer—is Vladimir Nabokov, who once wrote,“Curiously enough, one cannot read a book: one canonly reread it.” In this case, its not simply, as Rahulextolled, a way of reassessing; rather, its the onlyway to figure out whats in the material to begin with.Dozens of Chinese readers, from a wide rangeof backgrounds, have told me that they return toDream of the Red Chamber , if not annually, at leastas regularly as their schedules will allow. Both themusic critic Li Cheng and the composer Bright Shengdiscovered the novel as young teenagers, when neitherhad much inclination to linger over the poetry. Li gotcaught up in the narrative sweep; Sheng, who was thesame age as Baoyu, particularly marveled at a youngboy being surrounded by so many beautiful women.

I was a bit older by the time I arrived at the book,but being on deadline I didnt have much timefor the poetry either. Coming from outside theculture, I probably had a bit more patience readingdescriptions of elaborate banquets, or trying tofollow the rules to Jia familys drinking games.Long stretches of the novel have nothing to do withadvancing the plot. But heres the thing: readingthese discourses again, sometimes they do.

The first time around, I tolerated the elaboratediscourses concerning the abundant virtues andstringent esthetics of Chinese poetry while waiting toget back to the story. Only later did I realize that often,while ostensibly discussing poetry, the charactersare really talking about themselves. Initially, I wasfascinated that any family could support its ownopera troupe, and equally amused that, when thefamily funds start to dwindle, the troupe needs to bedissolved. “Rich-people problems,” wed say today.But in retrospect, fiscal imprudence put the Jia familyunder the proverbial viewing glass and the situationspirals downward from there.

Every time a story takes on new life, whether inlanguage or medium, the overriding question shouldbe, what does the new version add? For all its quirksand idiosyncrasies, the Hawkes-Minford translationapproaches the epic timelessness of the originalwhile opening the story to a broad range of non-Chinese readers. Regarding opera, the relationship israther less equitable.

Since opera by nature is reductive, the equationis mostly one of subtraction—in the extreme caseof Red Chamber, lopping off at least 380 characters,most of the narrative threads, and any action inthe remaining episodes not directly advancing thestory. Little time remains for family intrigue, drinkinggames or poetry circles—and considering that thelibretto is in English, no time at all for the language.By any objective measure, its hard to see what operahas to offer Dream of the Red Chamber.

But what does Red Chamber offer opera? That isa different proposition entirely. Given the generallyhigh emotional tone, multiple deaths, and thefinancial ruin of a prominent family, one would behard-pressed to find a more suitably operatic storyin world literature. But even more crucially, the keycharacters conveniently fall into internationallystandard dramatic and vocal types.

The impulsive Baoyu is, of course, a tenor (thinkCalaf); the gifted and sickly Daiyu reveals herselfas a consumptive soprano heroine worthy of Mimiand Violetta; the pragmatic and reliable Baochaibecomes—is anyone surprised here?—a mezzosoprano.Other family members, too, fall reliably inline. Structurally, the libretto shows that, once all thedigressions are removed (and some remaining detailsrearranged and compressed) the story smoothly fitsthe familiar emotional arc of most repertory operas.China has many stories to give the world, but few tickall the boxes for the operatic stage so neatly.

Though its still rather early to gauge Red Chamber splace in the repertory—well need to see what differentdirectors and other opera companies do with it—StanLais premiere production returning to San Franciscoalready bodes well. A matinee performance on June 19,live-streamed and available on demand worldwide for48 hours on the SFO website, will introduce new faceslike the Sichuan-born soprano Meigui Zhang (Daiyu),Guangzhou-based mezzo Hongni Wu (Baochai),Korean tenor Konu Kim (Baoyu) and Singapore-bornconductor Darrell Ang—all of whom making their SanFrancisco Opera debuts.

After finally reemerging from my Dream , I canhappily say that reading the full Hawkes-Minfordtranslation a second time does indeed deepen anunderstanding of the novel and provides a wealthof fresh insights into the characters and their world(particularly since I knew the story well enough tospot the clues in advance). Now its time to give theSheng-Hwang opera the same courtesy.