Influence of weight management on the prognosis of steatohepatitis in chronic hepatitis B patients during antiviral treatment

2021-11-08XuJuHuLuZuZuYuHuGuLuYuHuHuYuZuVtSu

Xu-Ju C ,,Y-W S ,,J W ,Hu-B Lu ,Y C ,X-N Zu ,Y-P C ,Zu-J Yu ,Q-Hu S ,L T ,Q L ,L J ,Gu-M X ,L C ,W Lu ,X-Yu Hu ,Q-Hu L ,L-J A ,Z-Yu Zu ,Vt W-Su W ,, Y-P Y ,, J-G F ,

a Department of Liver Disease, Chinese PLA General Hospital, the Fif th Medical Center of Chinese PL A General Hospital, Beijing 10 0 039, China

b Center for Fatty Liver, Department of Gastroenterology, Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai Key Lab of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Shanghai 20 0 092, China

c Department of Liver Disease, Affiliated Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 61007 2, China

d Department o f Liver Diseases, Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Chongqing, Chongqing 40 0 038, China

e Department of Infectious and Liver Diseases, Liver Research Center, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou 3250 0 0, China

f Department of Infectious Disease, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450 052, China

g Center of Therapeutic Liver Disease, the 960th Hospital of Chinese PL A, Taian 2710 0 0, China

h Liver Disease Department, Fuyang 2nd People’s Hospital, Fuyang 236015, China

i Department of Liver Diseases, Fuzhou Infectious Diseases Hospital, Fuzhou 350025, China

j Department of Infectious Diseases, Southwest Hospital, Army Military Medical University, Chongqing 40 0 038, China

k Department of Infectious Diseases, Guangzhou 8th People’s Hospital, Guangzhou 510060, China

l Department of Hepatic Diseases, Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, Shanghai 201508, China

m Department of Liver Diseases, Tianjin Second People’s Hospital, Tianjin Institute of Hepatology, Tianjin 300192, China

n National Integrative Med icine Clinical Base for Infectious Diseases and Department of Infectious Di seases, Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu 610 0 0 0, China,

o Department of Infection and Liver Disease, Yichun People’s Hospital, Yichun 336028, China

p Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Keywords: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis Hepatitis B NASH resolution Antiviral treatment Weight management

ABSTRACT Background: Although concomitant nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is common in chronic hepatitis B (CHB), the impact of viral factors on NASH and the outcome of CHB patients concomitant with NASH remain unclear. We aimed to investigate the outcomes of NASH in CHB patients receiving antiviral treat-ment. Methods: In the post-hoc analysis of a multicenter trial, naïve CHB patients receiving 72-week entecavir treatment were enrolled. We evaluated the biochemical, viral and histopathological responses of these patients. The histopathological features of NASH were also evaluated, using paired liver biopsies at base-line and week 72. Results: A total of 10 0 0 CHB patients were finally enrolled for analysis, with 18.2% of whom fulfilling the criteria of NASH. A total of 727 patients completed entecavir antiviral treatment and received the second biopsy. Serum HBeAg loss, HBeAg seroconversion and HBV-DNA undetectable rates were similar between patients with or without NASH ( P > 0.05). Among patients with NASH, the hepatic steatosis, ballooning, lobular inflammation scores and fibrosis stages all improved during follow-up (all P < 0.001), 46% (63/136) achieved NASH resolution. Patients with baseline body mass index (BMI) ≥23 kg/m 2 (Asian criteria) [odds ratio (OR): 0.414; 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 0.190-0.899; P = 0.012] and weight gain (OR: 0.187; 95% CI: 0.050-0.693; P = 0.026) were less likely to have NASH resolution. Among patients without NASH at baseline, 22 (3.7%) developed NASH. Baseline BMI ≥23 kg/m 2 (OR: 12.506; 95% CI: 2.813-55.606; P = 0.001) and weight gain (OR: 5.126; 95% CI: 1.674-15.694; P = 0.005) were predictors of incident NASH. Conclusions: Lower BMI and weight reduction but not virologic factors determine NASH resolution in CHB. The value of weight management in CHB patients during antiviral treatment deserves further eval-uation.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection affects more than 292 mil-lion people (3.9%) worldwide. It significantly increases the risk of the development of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver-related mortality [1] . Although current potent antiviral ther-apies can maintain viral suppression and reduce the risk of liver-related complications, we could not completely eliminate the in-fection because of the persistent HBV minichromosome in infected cells [ 2,3 ]. With the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), concomitant NAFLD is common in treatment-naïve CHB patients. It is estimated that the prevalence of hepatic steatosis in CHB patients ranges from 17% to 25% [ 4,5 ].

As a more aggressive subtype of NAFLD, nonalcoholic steato-hepatitis (NASH) is characterized by the presence of steatosis, inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning, generally considered to have faster fibrosis progression than simple steatosis [6] . Dis-ease progression in NASH results in various liver-related outcomes. There have been no approved pharmacologic therapies for the treatment of NASH [7] . Although various studies on the interac-tion between NAFLD and CHB have been conducted, the interac-tion between the two diseases remains controversial [ 8–10 ]. Not only the impact of NASH on antiviral therapy but also the nat-ural history of NASH during antiviral therapy is unclear. In addi-tion, a recent study showed that CHB patients with superimposed NASH have poorer clinical outcomes [11] . Some studies have in-vestigated the effects of CHB and concomitant NAFLD on liver dis-ease [ 12–14 ], while few multicenter prospective studies have in-cluded biopsy-defined NASH. Many previous studies were cross-sectional designed, which cannot clearly define the relationship be-tween NASH and CHB [ 15,16 ].

Considering the rapidly increasing incidence of NASH, concomi-tant CHB and NASH is expected to become more common in the near future. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the impact of NASH on antiviral treatment response in CHB patients, and to investigate the outcomes of NASH in CHB patients receiving antiviral treat-ment.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a post-hoc analysis of a multicenter, prospective, ran-domized controlled trial on long-term HBV treatment outcomes (NCT01965418) [ 17,18 ]. Patients were prospectively recruited from 14 centers of China.

Patients fulfilling the following criteria were enrolled in the study: aged ≥18 years and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive for ≥6 months; Ishak fibrosis staging of ≥3; and an-tiviral treatment-naïve or no treatment for at least 6 months. The exclusion criteria included excessive alcohol consumption (>20 g/day for women or>30 g/day for men); history of malignancy including HCC; other causes of liver disease including co-infection with hepatitis C or D; receiving potential medical interventions for NAFLD; diabetes requiring hypoglycemic drugs; serious uncontrol-lable diseases, organ transplantation or HIV; pregnancy or lacta-tion.

All patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive Biejia-Ruangan (BR) tablet or placebo tablets (2 g three times daily) af-ter enrollment. Patients in both groups also received entecavir 0.5 mg/day. BR tablet was a quintessence complex of traditional Chi-nese medicine, approved by the National Medical Products Admin-istration (NMPA) of China for the treatment of cirrhosis.

Histopathological evaluation

Liver biopsy at baseline and follow-up was performed with ul-trasound guidance using 16 G quick-cut needle or Menghini needle (Allegiance Corporation, Waukegan, IL, USA). At least two pieces of liver tissue with more than 11 portal tracts each were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), reticulin, and Masson’s trichrome. Two central liver pathologists blinded to clinical information as-sessed all biopsy samples independently.

Necroinflammation activity of CHB was assessed by the Ishak modified histology activity index (HAI) grading system. Fibrosis of CHB was also scored by Ishak staging system, in which Ishak stage 5 to 6 was defined as cirrhosis [19] . Noninvasive fibrosis test in-cluding liver stiffness measurement (LSM), aspartate aminotrans-ferase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI) and fibrosis 4 index (FIB-4) were calculated. The histopathological features of NAFLD were evaluated according to the system developed by NASH Clinical Re-search Network (NASH-CRN) [14] . The NAFLD activity score (NAS) ranged from 0 to 8 including steatosis scores (0-3), lobular in-flammation scores (0-3) and hepatocellular ballooning scores (0-2). Liver fibrosis for NAFLD was staged 0-4 according to the Kleiner fi-brosis stage [20] .

Treatment efficacy and working definitions

The efficacy of antiviral treatment consists of virological re-sponse (including undetectable HBV-DNA), biochemical response [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) normalization] and histological re-sponse. HBeAg seroconversion is defined as the absence of HBeAg and the presence of antibody in HBeAg-positive patients. ALT nor-malization is defined as ≤upper limit of normal (40 U/L) of ALT at week 72. Fibrosis regression is defined as decrease in Ishak fi-brosis score by ≥1 stage. Histological improvement is defined as ≥2-point decrease in the modified HAI score and no worsening of fibrosis compared to baseline [21] .

NAFLD is defined as the presence of ≥5% steatosis without sec-ondary causes according to the Chinese guidelines on NAFLD [22] . NASH is defined as the presence of ≥5% steatosis with lobular in-flammation and hepatocyte ballooning. Advanced fibrosis refers to stages 3 or 4 fibrosis in patients with NASH. NASH resolution is defined as absent or bland steatosis without steatohepatitis: 0-1 for inflammation score, 0 for ballooning score, and any score for steatosis [23] . NASH improvement is defined as a decrease in in-flammation score ≥1 point and a decrease in ballooning score ≥1 point, without worsening of fibrosis, defined by NMPA [24] .

For Asian population, overweight is defined as body mass in-dex (BMI) higher than 23 kg/m2. Weight change is calculated as (weight at baseline-weight at week 72)/weight at baseline ×100%. Weight gain is defined as ≥1% increase compared to baseline.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean ±standard deviation, and analyzed by Student’st-test. Oth-erwise, median with interquartile range (IQR) was used in case of not normally distributed data, and analyzed by Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis test. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used for comparison among three or more groups, when the data conformed to normal distribution and homogeneity of variance. Changes in the histological scores from baseline and week 72 were evaluated using Wilcoxon rank sum test for the paired data. Uni-variate and multivariate binary logistic regression analyses were performed to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of the associated factors for NASH resolution, NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis, NAS decrease more than 2 points, NASH improvement without progression of fibrosis, as well as incident NASH among CHB patients receiving antiviral therapy. Collinearity diagnostics among variables were estimated with generalized linear models. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, Version 25.0).

Results

Baseline characteristics of enrolled CHB patients

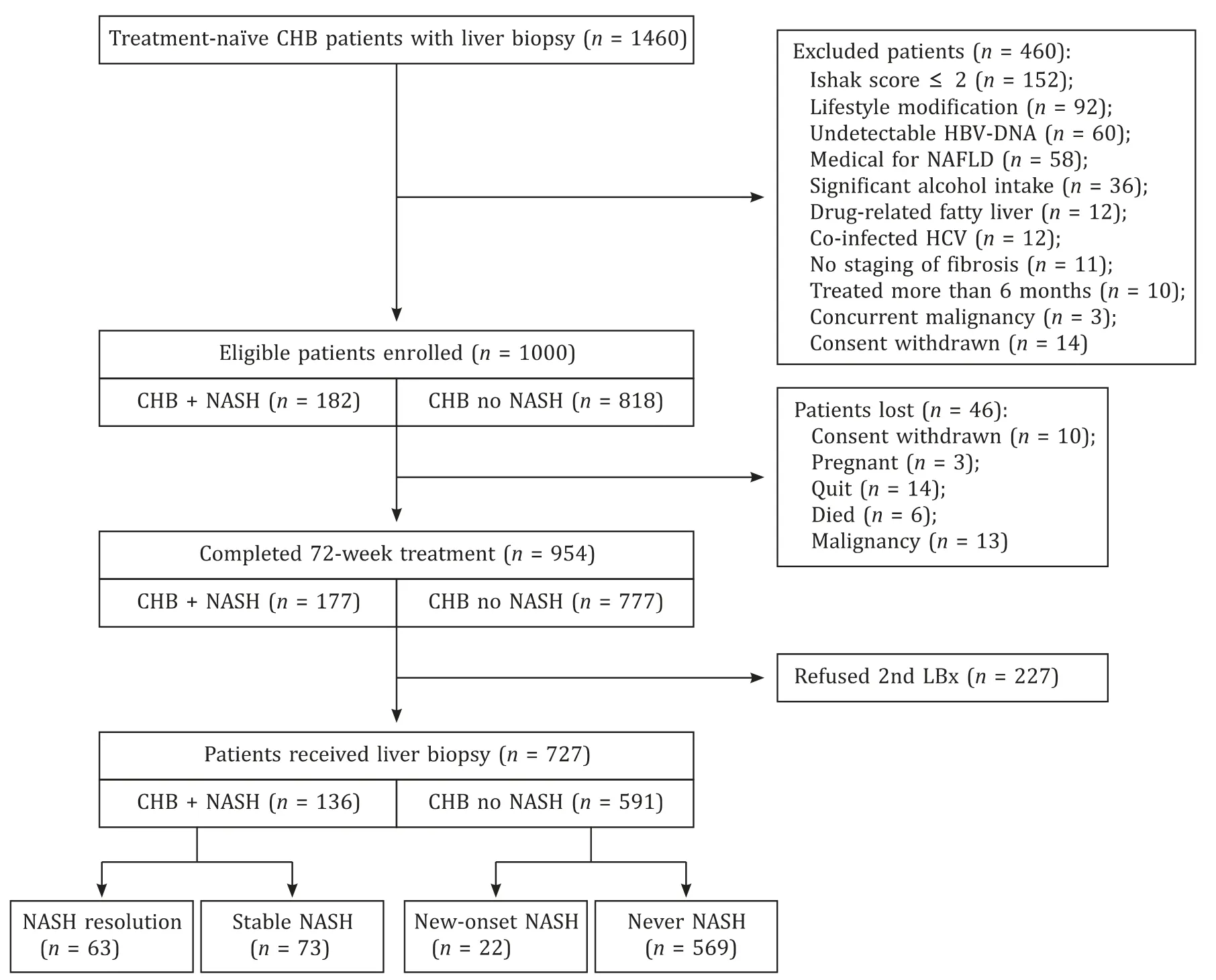

From October 2013 to October 2014, a total of 1460 patients with CHB were screened for eligibility from 14 centers. Finally, 10 0 0 CHB patients were enrolled to receive antiviral treatment. Among the patients, 29.7% (297/10 0 0) had steatosis, and 18.2% (182/10 0 0) fulfilled the criteria of NASH at the first liver biopsy. During 72-week treatment, 46 patients were lost to follow up. Among 954 patients completing the antiviral treatment, 727 took the second liver biopsy and were included for the final analysis ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the study design and patient outcome. CHB: chronic hepatitis B; NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; LBx: liver biopsy.

CHB patients with NASH had higher BMI, higher proportion of overweight and higher steatosis score compared to those without NASH (allP<0.001) ( Table 1 ). In virology, CHB patients with NASH had higher levels of serum HBV-DNA (6.46 log IU/mL vs. 6.09 log IU/mL,P= 0.005). CHB patients with NASH also had more severe degree of inflammation: they had higher proportion of elevated ALT (P= 0.015) and higher HAI scores (P<0.001) than those with-out NASH. Whereas, the two groups had similar fibrosis stages in terms of Ishak fibrosis score (P= 0.807) and LSM value (P= 0.224).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics between chronic hepatitis B patients with and without NASH.

Table 2 Treatment efficacy between CHB patients with vs. without NASH.

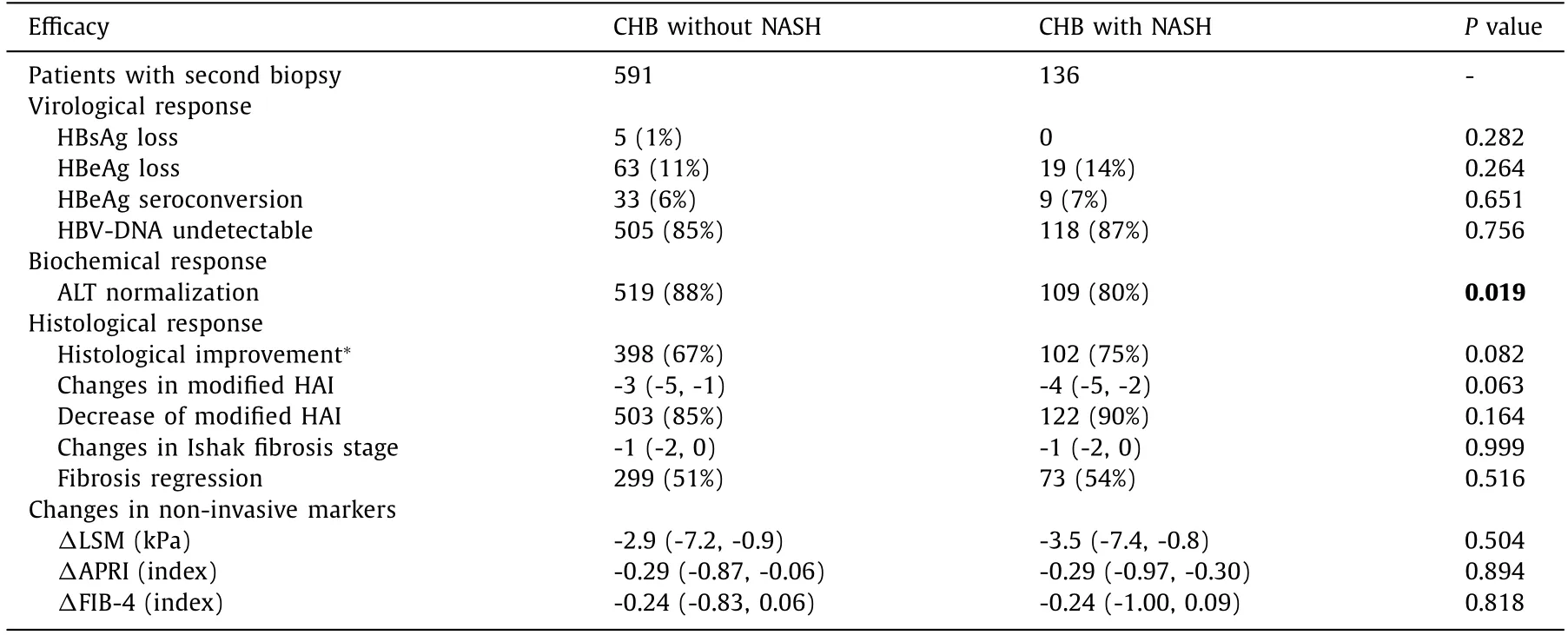

Concomitant NASH did not af fect response to antiviral therapy in CHB

Among CHB patients completing 72-week antiviral treatment, 136 with NASH and 591 without NASH received the second biopsy. The rates of undetectable HBV-DNA, HBeAg loss and HBeAg se-roconversion were similar between the two groups (P= 0.756,P= 0.264 andP= 0.651, respectively). Patients with NASH had lower ALT normalization rate than those without NASH (80% vs. 88%,P= 0.019). Although serum HBsAg loss was achieved in pa-tients without NASH only (n= 5, 1%), the difference between two groups did not reach statistical significance (P= 0.282).

The patients in two groups also achieved significant histologi-cal improvements. About 85% patients with and 90% without NASH had a decreased HAI score at week 72 (P= 0.164). The fibrosis re-gression rates were similar between the two groups (51% vs. 54%,P= 0.516). The non-invasive tests of fibrosis including LSM, APRI and FIB-4 were also significantly decreased, and there was no sig-nificant difference between two groups (P= 0.504,P= 0.894 andP= 0.818, respectively). About 75% patients with and 67% without NASH achieved histological improvement (P= 0.082, Table 2 ).

Improvements in the histology of patients with NASH

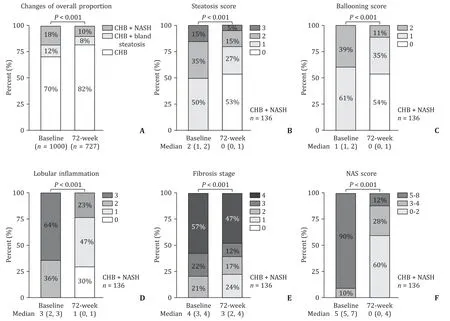

The changes in the proportion of hepatic steatosis and steato-hepatitis were shown in Fig. 2 A. Among 136 patients with NASH completing 72-week antiviral therapy, 50% had moderate to se-vere steatosis (steatosis ≥2) at baseline, while only 20% still had moderate to severe steatosis at week 72 (P<0.001) after treat-ment. Similarly, scores of ballooning and lobular inflammation in patients with NASH were significantly decreased at week 72 (bothP<0.001). The NAS score of patients with NASH was also im-proved at week 72. The median NAS score decreased from 5 (5-7) points to 0 (0-4) points, with only 16/136 patients (12%) having NAS score>4 points at week 72. The proportion of significant fi-brosis (F ≥2) decreased from 100% to 76%, and the overall fibrosis stages were improved compared to baseline (P<0.001, Fig. 2 B-F).

Fig. 2. Dynamic changes in the histological characteristics of NASH during antiviral treatment. A: Changes of the proportion of patients with NASH or bland steatosis at week 72. Changes in the histological characteristics in CHB patients with NASH: steatosis grade (B),ballooning score (C),lobular inflammation score ( D ), fibrosis stage by Kleiner stage (E),NAS score (F) .

A total of 63 patients (46%) achieved NASH resolution, and 58 (43%) achieved NASH resolution without progression of fibrosis. A total of 74% (100/136) patients with NASH had a decrease in steato-sis grade, with a median from 2 (1-2) to 0 (0-1). Most of the patients (128/136, 94%) had a decrease in NAS score. A decrease of NAS ≥2 points was achieved in 115/136 (85%) patients with NASH. As defined by NMPA, NASH improvement without progres-sion of fibrosis was also achieved in 59% (80/136) of the patients. Up to 43% (59/136) patients also had fibrosis regression, with 40% (55/136) patients having no progression of NASH at the same time.

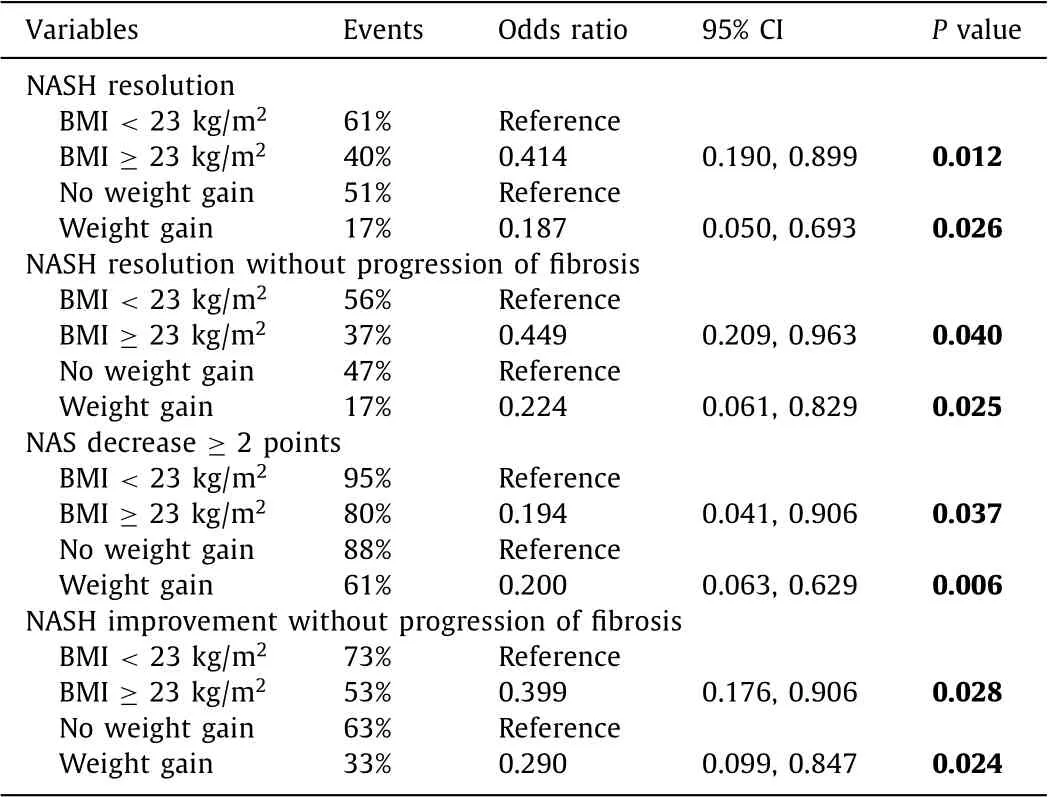

Overweight and weight gain were negative factors for NASH resolution

The ORs for key characteristics of main NASH outcomes includ-ing NASH resolution, NASH resolution without progression of fi-brosis, NAS decrease ≥2 points and NASH improvement with no progression of fibrosis were shown in Table 3 . After adjusting for sex, age, history of smoking and drinking, positive HBeAg, HBV-DNA level, quantitative HBsAg level at baseline, ALT normalization and HBV-DNA undetectable, baseline overweight (OR: 0.414; 95% CI: 0.190-0.899;P= 0.012) and weight gain (OR: 0.187; 95% CI: 0.050-0.693;P= 0.026) were independent negative factors associ-ated with NASH resolution ( Table 3,Table S1). In these logistic re-gression analyses, there was no interaction between baseline BMI and weight change (Pvalue interaction = 0.531, 0.564,>0.999, 0.149, respectively).

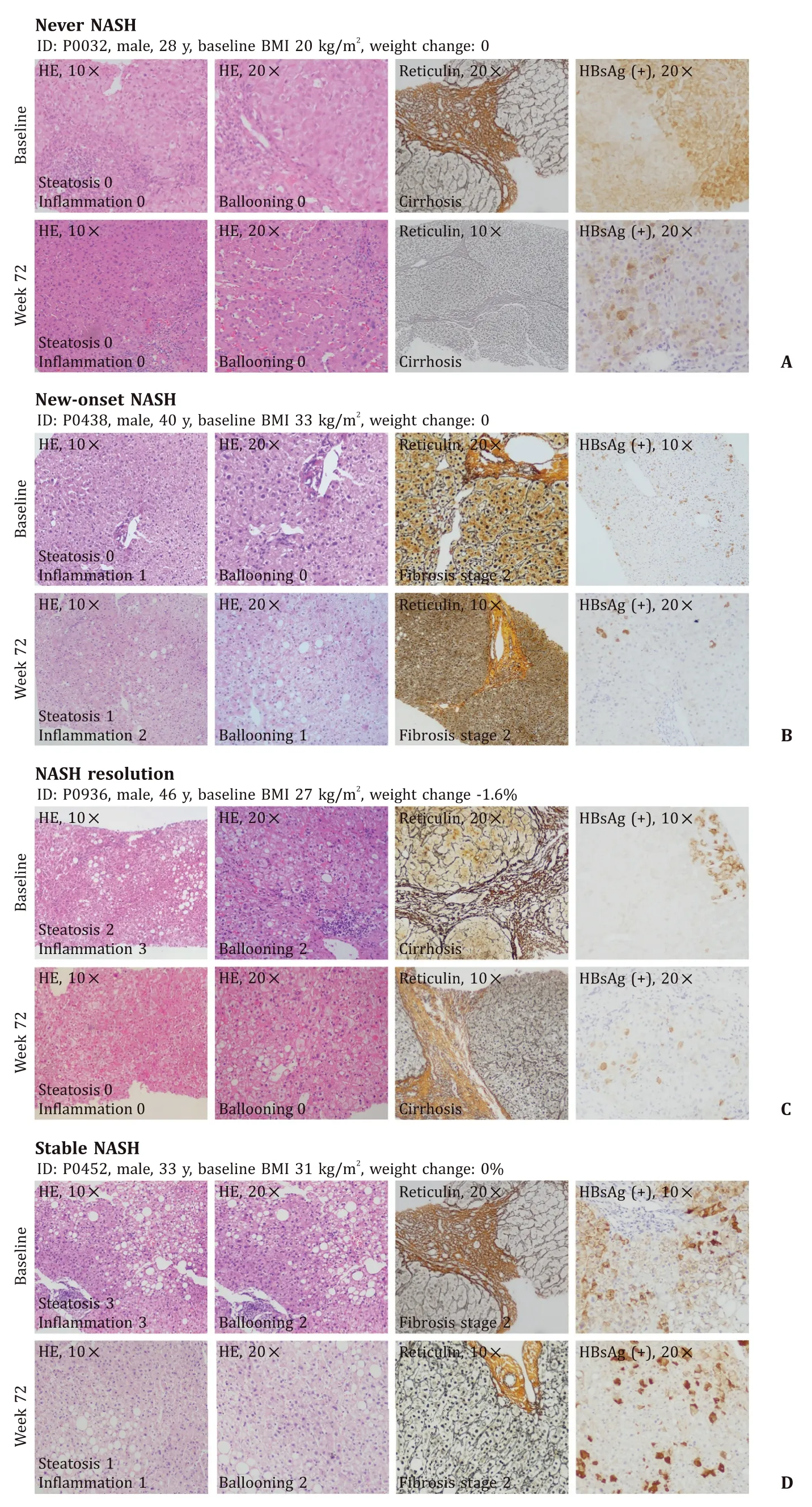

Similarly, overweight at baseline and weight gain during follow-up were less likely to have NASH resolution without progression of fibrosis, NAS decrease ≥2 points and NASH improvement without progression of fibrosis ( Table 3,Table S2-4). In addition, the resolu-tion rates were similar between groups with and without BR treat-ment (Table S5). The combined BR tablet treatment had no effects on NASH resolution (OR: 0.934; 95% CI: 0.476-1.834), NASH reso-lution without progression of fibrosis (OR: 0.871; 95% CI: 0.441-1.720), NAS decrease ≥2 (OR: 0.664, 95% CI: 0.260-1.697), nor NASH improvement without progression of fibrosis (OR: 1.022, 95% CI: 0.516-2.023) in CHB patients with NASH (Table S1-4). The his-tological characteristics of patients never with NASH, newly onset NASH, NASH resolution and stable NASH were shown in Fig. 3 .

Table 3 Risk factors associated with the outcomes of NASH.

Fig. 3. Variety in histologic outcomes during treatment of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients. Four different types of outcomes in CHB patients showed in liver biopsy samples: no NASH at baseline or 72-week follow-up (A) ; no NASH at baseline but developed NASH at week 72 (B) ; CHB patients had NASH resolution at week 72 (C) ; CHB patients had NASH at baseline and week 72 (D) . NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; BMI: body mass index; H&E: hematoxylin-eosin staining.

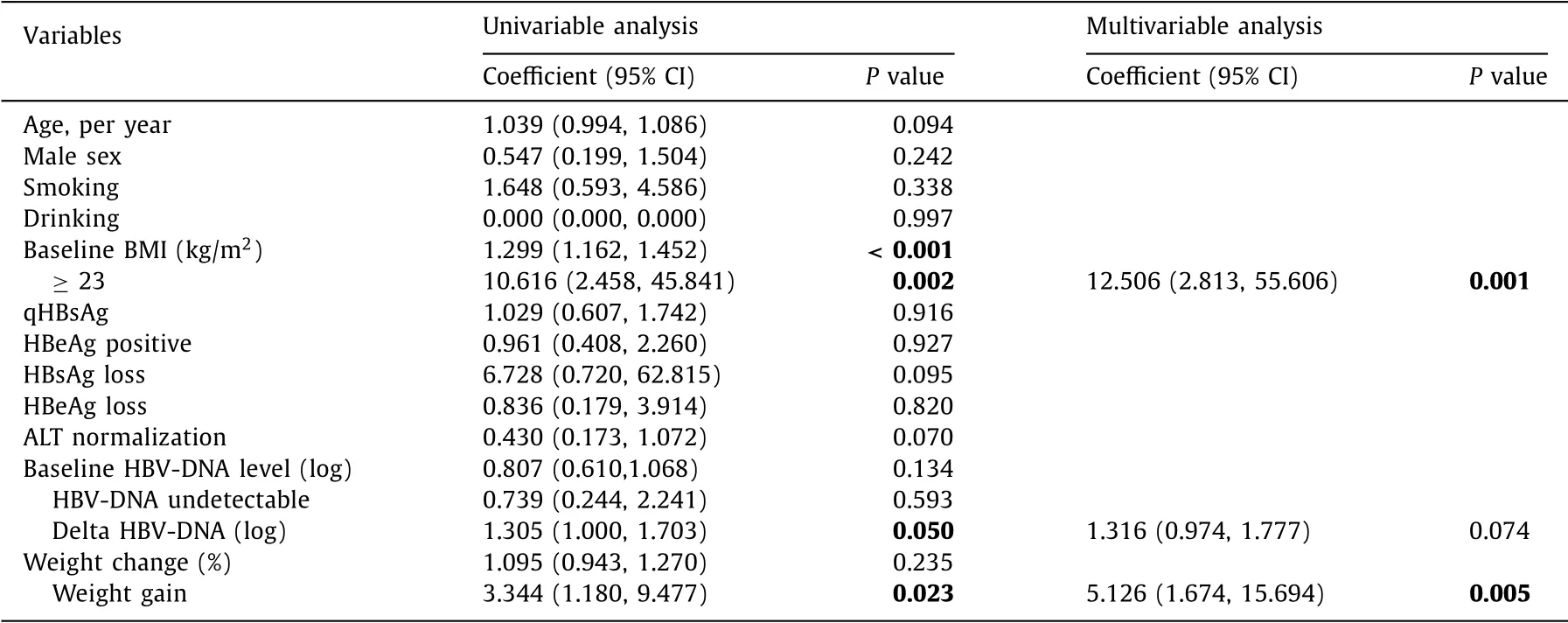

Weight status and NASH outcomes during antiviral treatment of CHB

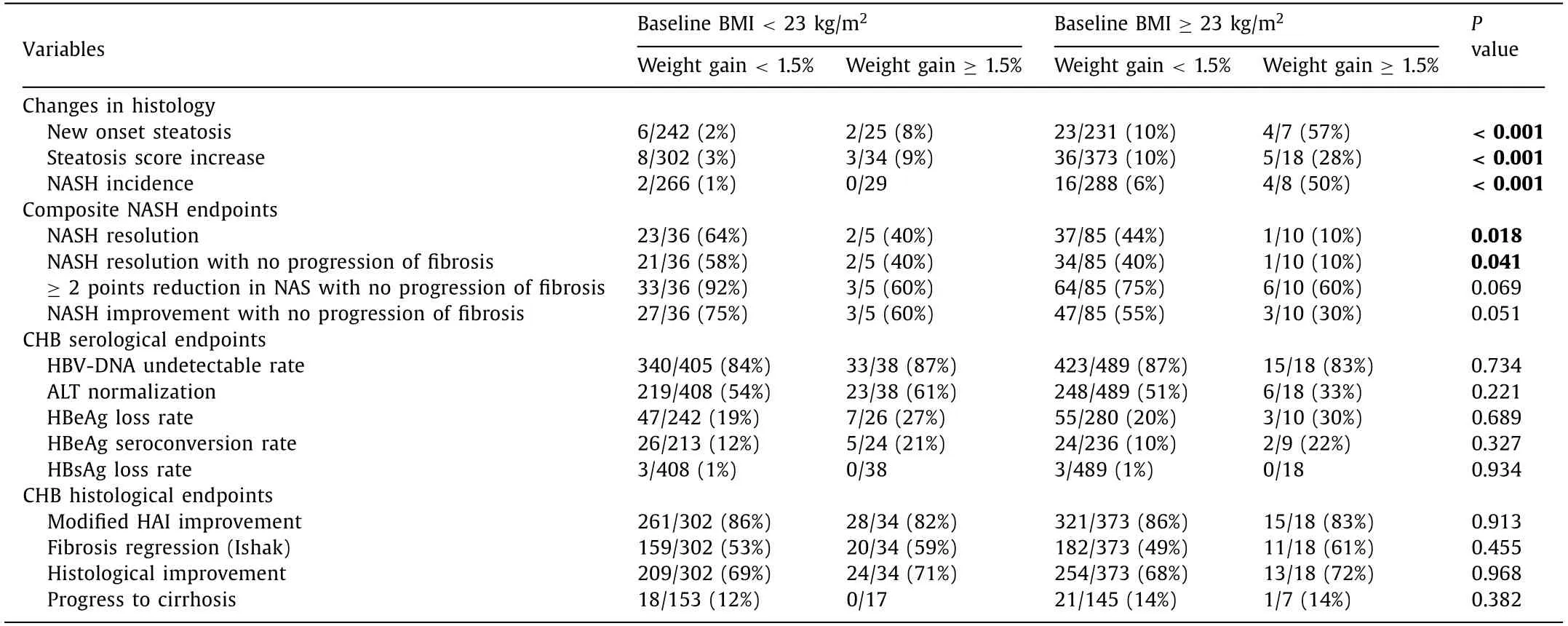

Among CHB patients without steatosis at baseline, 7% (35/505) had newly onset steatosis during follow-up, with an incidence of 50.0 per 10 0 0 person-years. Among CHB patients who had no or bland steatosis at baseline, 22 (4%) developed NASH at the end of follow-up, with an incidence as 14.4 per 10 0 0 person-years. Patients with overweight had 12.5 times (95% CI: 2.813-55.606;P= 0.001) risk of developing NASH, while patients with weight gain during follow-up had 5.1 times (95% CI: 1.674-15.694;P= 0.005) risk of developing NASH ( Table 4 ).

Overall, the proportions of patients with NASH resolution, sta-ble NASH, new-onset NASH and never NASH were 9%, 10%, 3% and 78%, respectively. Baseline BMI and weight change during follow-up were significantly associated with outcomes of NASH in CHB patients receiving antiviral treatment. The proportion of weight gain in these groups was 5%, 27%, 23% and 8%, respectively. Over-weight CHB patients with weight gain ≥1.5% during follow-up had the highest risk of developing new-onset steatosis, increasing de-gree of steatosis and incident NASH (allP<0.001, Table 5 ). These patients also had the lowest rate of NASH resolution (P= 0.018), NASH resolution with no progression of fibrosis (P= 0.041), and a tendency of lower rate of ≥2 points reduction in NAS with no progression of fibrosis (P= 0.069) and NASH improvement with no progression of fibrosis (P= 0.051, Table 5 ).

Table 4 Risk factors of the incidence of NASH in CHB patients.

Table 5 Baseline BMI and weight gain were associated with the outcomes of NASH in CHB patients.

Discussion

Numerous studies focused on the impact of hepatic steatosis on the virologic response of CHB, while few studies examined the outcomes of co-existing NASH in patients with CHB during an-tiviral treatment [ 25–27 ]. In this large-scale, multi-center, paired liver biopsy-proven antiviral treatment study, we observed that the outcome of patients with concomitant NASH was closely associ-ated with baseline BMI and subtle weight change rather than vi-ral response during treatment. These results call for the need of increased awareness in the weight management during antiviral treatment of CHB patients.

To our knowledge, this is the first study using paired liver biop-sies to investigate the outcomes of CHB patients with NASH in a large cohort with antiviral therapy. Most of the previous stud-ies evaluated the grade of steatosis by ultrasonography [ 25,28,29 ], which is not sensitive enough to detect mild to moderate steatosis and its subtle changes. Furthermore, histopathological assessment remains indispensable in the diagnosis of NASH. In the present study, the scoring systems we used to assess the features of active inflammation and fibrosis in NAFLD and CHB were independent. The activity of hepatitis B (modified HAI) consists of the severity of four aspects including periportal interface hepatitis, confluent necrosis, focal lytic necrosis and portal inflammation [19] . While in NAFLD, the inflammation is determined by the numbers of lobular inflammation foci per field and ballooned hepatocytes [14] ; the lat-ter in particular is well recognized as a key feature of NASH. Recent evidence also showed that the histological activity of hepatitis B is not correlated with the severity of steatosis or NASH [30] . Thus, we could avoid the bias brought by the improvement of hepatitis B due to antiviral treatment when assessing the activity of NAFLD.

Although a high proportion of naïve CHB patients had concomi-tant NASH at baseline, we observed a high NASH resolution rate af-ter 72-week antiviral treatment. Compared to previous reports, the NASH resolution rate in our study was even higher than that in the control arm of novel agents clinical trials [ 31,32 ]. As demonstrated by previous studies, weight change played an important role in the resolution of NASH [ 33,34 ]. Overweight/obesity and weight gain in adulthood are closely associated with the development of NAFLD in the general population [ 35–37 ]. In non-obese patients, improve-ments in NAFLD or NASH can even be achieved by a small re-duction of weight [ 34,38 ]. A recent report in CHB patients also had similar findings [39] . We also reported the incidence of NASH in CHB patients during antiviral therapy for the first time. Our data (50.0/10 0 0 person-years) were similar with the recent report of incident ultrasound-based NAFLD in CHB patients (63.89/10 0 0 person-years) [39],and slightly higher than that in general popu-lation (28.6/10 0 0 person-years reported by Zelber-Sagi et al. [40],29.7/10 0 0 person-years reported by Chang et al. [41] ). Similar with the previous cohort study of metabolically normal patients, BMI of the patients was associated with the incidence of NAFLD [41] . Therefore, we should pay enough attention to body weight control and healthy lifestyle in CHB patients regardless of antiviral treat-ment.

One previous study showed that HBV may have interactions with hepatic steatosis through multiple mechanisms [42] . HBV X protein (HBx) and HBV surface proteins play a role in the hepatic lipid deposition and lipogenesis [ 43,44 ]. Although antiviral agents including entecavir could down-regulate the expression of HBx [45],there is no evidence that entecavir had direct effect on the regulating lipid metabolism [46] . The combined BR tablet is a traditional Chinese medicine, consequently used for liver cirrhosis in China [47] . In the current study, BR tablet showed no effect on the resolution or improvement of steatohepatitis in fibrotic patients with CHB. The pathogenesis of HBV-associated hepatic steatosis still remains elusive, and more evidences from molecular pathways and experimental animal models are needed. In addition, novel antiviral agents such as tenofovir alafenamide and myrcludex B showed potential efficacy in improving metabolic dysfunctions including weight loss and decreased hepatic adiposity [ 4 8,4 9 ]. These new agents may be promising in the management of CHB patients concomitant with NASH or NAFLD.

Another important question concerning the NASH in HBV in-fected patients is whether the steatosis had impact on the re-sponse to antiviral therapy. Most of previous studies investigat-ing this issue were retrospective and single-center, using indirect methods such as imaging to evaluate steatosis [ 50,51 ]. By avoiding these limitations, this study was based on histological evidence of NASH, a multicenter prospective cohort and therefore could specif-ically explore the impact of NASH on antiviral treatment response. In our study, concomitant NASH did not affect the antiviral effi-cacy of CHB. The HBV-DNA undetectable rates were similar be-tween CHB patients with and without NASH at week 72, in accor-dance with the recent study [52] . Compared with real-world study mentioned above, the present study was a clinical trial, and strict inclusion and exclusion criteria would reduce the effect of someconfounders. Based on the histologic evidence of NASH and a mul-ticenter prospective cohort, we believe that our findings could pro-vide a reliable inference that there is no significant impact of NASH on treatment response under antiviral therapy.

Several limitations of the current study need to be consid-ered. First, there was no control group of CHB patients with NASH not receiving antiviral treatment, for it would be unethi-cal to leave patients with treatment indications untreated. Sec-ond, limited to previous design of the original study, the impact of metabolic characteristics including lipid profile, plasma glucose and insulin on the outcome of NASH was not analyzed. Fortu-nately, patients taking hypoglycemic agents or potential treatment for NAFLD were excluded in this study, which reduced confound-ing. Third, we did not observe any significant difference in fibro-sis improvement between patients with or without weight gain. A total of 72 weeks is still short for the significant changes of fibrosis attributed to NASH. In addition, this follow-up study is now going on. Future results of our current study, along with an-imal studies promise to further reveal the mechanism of resolu-tion and incident NASH in CHB patients receiving antiviral treat-ment. We hope that data in the near future would add more evidences.

In conclusion, viral response is not associated with the outcome of NASH in naïve CHB patients receiving 72-week entecavir ther-apy. BMI at baseline and subtle weight changes during follow-up are important either in the resolution or in the incidence of NASH in CHB patients during antiviral treatment. Therefore, we should pay attention to body weight control in CHB patients regardless of antiviral treatment.

Acknowledgments

None.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Xiu-Juan Chang:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing -orig-inal draft.Yi-Wen Shi:Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writ-ing -original draft.Jing Wang:Data curation.Hua-Bao Liu:Data curation.Yan Chen:Data curation.Xiao-Ning Zhu:Data curation.Yong-Ping Chen:Data curation.Zu-Jiang Yu:Data curation.Qing-Hua Shang:Data curation. Lin Tan:Data curation.Qin Li:Data cu-ration.Li Jiang:Data curation.Guang-Ming Xiao:Data curation.Liang Chen:Data curation.Wei Lu:Data curation.Xiao-Yu Hu:Data curation.Qing-Hua Long:Data curation.Lin-Jing An:Data curation.Zi-Yuan Zou:Writing -original draft.Vincent Wai-Sun Wong:Conceptualization, Writing -original draft, Writing -review & editing.Yong-Ping Yang:Conceptualization, Data curation, Fund-ing acquisition, Writing -original draft, Writing -review & editing.Jian-Gao Fan:Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisi-tion, Writing -original draft, Writing -review & editing.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Ma-jor Special Project for the Prevention and Treatment of Major Infectious Diseases: AIDS and viral hepatitis (2013ZX10 0 050 02, 2018ZX10725506) and the National Key Research and Development Program (2017YFC0908903).

Ethical approval

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of each participating institution and written informed consents were obtained from all patients.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the sub-ject of this article.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.hbpd.2021.06.009 .

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Comparison and development of advanced machine learning tools to predict nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: An extended study

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Key factors and potential drug combinations of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Bioinformatic analysis and experimental validation-based study

- LC-MS-based lipidomic analysis in distinguishing patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis from nonalcoholic fatty liver

- Cryptococcosis in patients with liver cirrhosis: Death risk factors and predictive value of prognostic models

- Gene knockout or inhibition of macrophage migration inhibitory factor alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury via inhibiting inflammatory response