Preemptive endoluminal vacuum therapy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A case report

2021-01-11FlaubertSenadeMedeirosEpifanioSilvinodoMonteJuniorRomerodeLimaFranHeliClvisdeMedeirosNetoJulianyMedeirosSantosEligioAlvesAlmeidaniorSamuelOliveiradaSilvaniorMarioHermanSantosMouraPedreiraTavaresEduardoGuimaresHourne

Flaubert Sena de Medeiros, Epifanio Silvino do Monte Junior, Romero de Lima França, Heli Clóvis de Medeiros Neto, Juliany Medeiros Santos, Eligio Alves Almeida Júnior, Samuel Oliveira da Silva Júnior, Mario Herman Santos Moura Pedreira Tavares, Eduardo Guimarães Hourneaux de Moura

Abstract BACKGROUND Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a technically demanding operation, with reported morbidity rates of approximately 40%–50%. A novel idea is to use endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT) in a preemptive setting to prevent anastomotic leakage and pancreatic fistulas. In a recent case series, EVT was proven to be effective in preventing leaks in patients with anastomotic ischemia. There have been no previous reports on preemptive EVT after pancreaticoduodenectomy.CASE SUMMARY We describe the case of a 71-year-old woman with hypertension and diabetes who was admitted to the emergency room with jaundice, choluria, fecal acholia,abdominal pain, and fever. Admission examinations revealed leukocytosis and hyperbilirubinemia (total: 13 mg/dL; conjugated: 12.1 mg/dL). Abdominal ultrasound showed cholelithiasis and dilation of the common bile duct. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a stenotic area, and a biopsy confirmed cholangiocarcinoma. Considering the high risk of leaks after pancreaticoduodenectomy, preemptive endoluminal vacuum therapy was performed. The system comprised a nasogastric tube, gauze, and an antimicrobial incise drape. The negative pressure was 125 mmHg, and no adverse events occurred. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 5 without any symptoms.CONCLUSION Preemptive endoluminal vacuum therapy may be a safe and feasible technique to reduce leaks after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Key Words: Preemptive; Endoluminal; Vacuum; Pancreaticoduodenectomy; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a technically demanding operation, with reported morbidity rates of approximately 40%-50%. Gastroparesis and bleeding are the most frequent complications, while pancreatic fistula, which can cause intra-abdominal abscess, sepsis, and occasionally death, is the most serious. Patients may require another operation, representing a therapeutic challenge that directly impacts mortality,morbidity, and cost to health systems worldwide. Several techniques, such as pancreatic duct occlusion, pancreatogastric anastomosis, Wirsung-jejunal duct-tomucosa anastomosis, and drainage to the pancreatic duct, have been developed to prevent complications.

In recent years, endoscopic procedures have begun to fill the large gap between medical and surgical treatments aimed at avoiding fistulas and leaks. There have been no previous reports of preemptive endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT) after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 71-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency room with jaundice, choluria,fecal acholia, abdominal pain, and fever.

History of present illness

The patient had a 6-day history of worsening abdominal pain and fever 2 d before admission at the emergency unit.

History of past illness

She had a medical history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus, controlled with oral agents.

Personal and family history

She had not undergone any prior abdominal surgery.

Physical examination

Physical examination revealed fever (38.5°C), jaundice, and tenderness in the upper abdomen.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory tests revealed elevated serumbilirubin levels (total: 13 mg/dL; conjugated:12.1 mg/dL), leukocytosis (white blood cells: 16500/µL), and reduced serum albumin levels (2.1 g/dL). Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen levels were within normal limits.

Imaging examinations

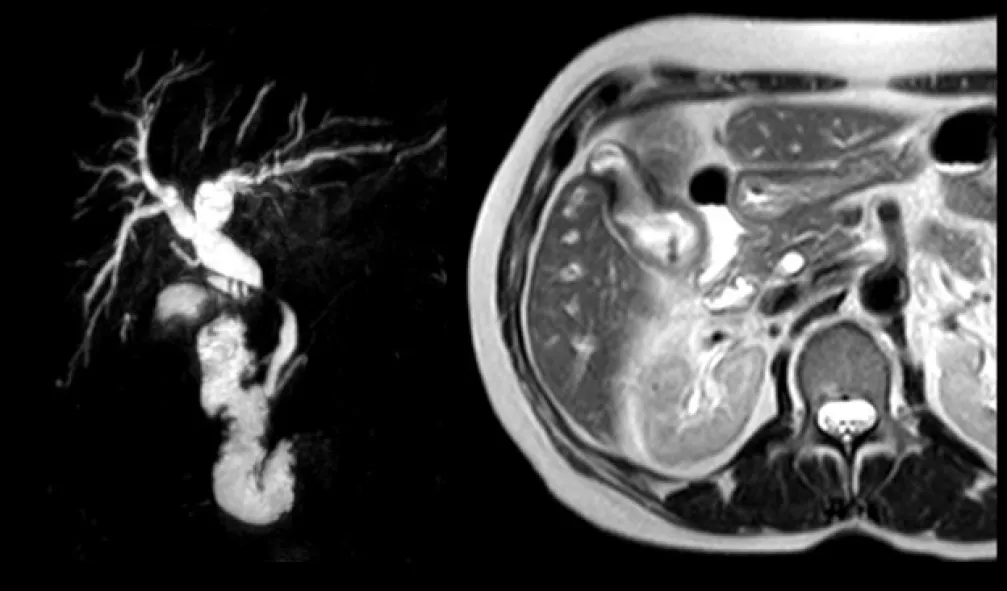

Abdominal ultrasonography showed cholelithiasis and intrahepatic and extrahepatic dilatations. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a circumferential tumor of the middle bile duct with upstream biliary dilatation, cholangitis, and cholelithiasis(Figure 1). The pancreas and caliber of the duct of Wirsung were normal. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed, although drainage was unsuccessful because the guidewire could not be passed across the lesion.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The patient was diagnosed with mo derately differentiated biliary adenocarcinoma pT4pN0pM0 (stage group IIIB).

TREATMENT

Considering the success of ERCP, we opted for percutaneous drainage. The patient had a history of weight loss, reduced serum albumin levels (2.1 g/dL), and lower oral food intake. Therefore, enteral nutrition was initiated through a nasoenteral feeding tube and high-protein oral supplementation.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Figure 2) was performed on hospital day 14, after tumor staging and perioperative nutrition. A laparoscopic approach was attempted, although the procedure was converted to open pancreaticoduodenectomy because of bleeding from a branch of the portal vein. A harmonic power clamp was applied to a pancreatic section, showing a thin duct of Wirsung. End-to-side duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy and choledochal-jejunal anastomosis were performed with Caprofyl. The surgical procedure lasted 10 h, requiring blood transfusion (4 units of red blood cells). The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, where she remained for 1 d.

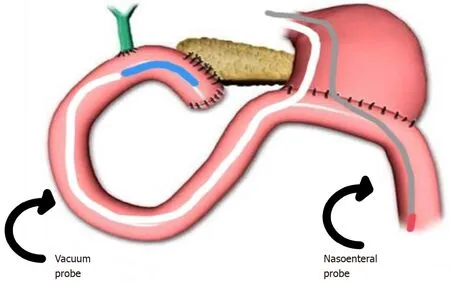

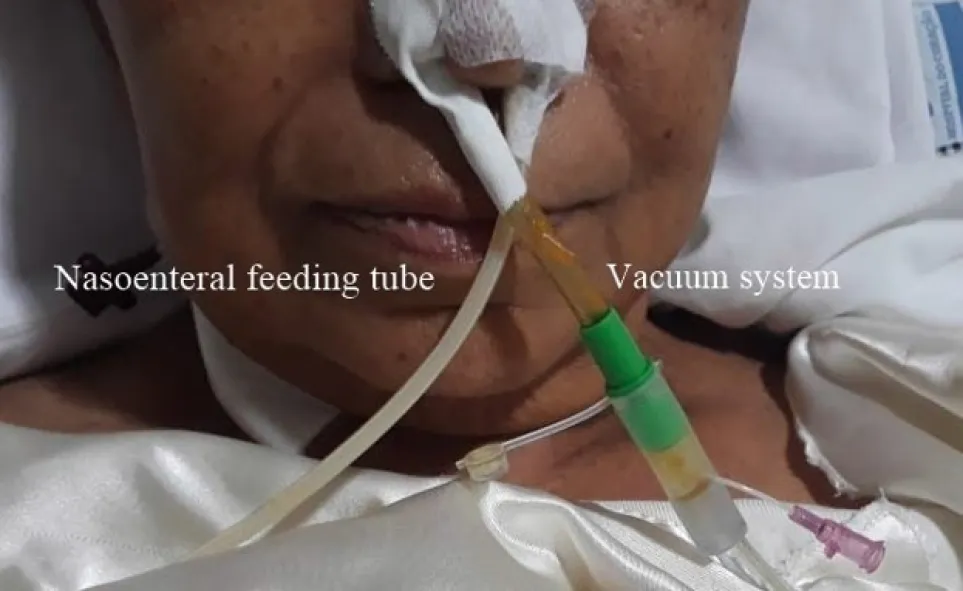

Preemptive endoluminal vacuum therapy was provided during surgery. The system implemented the Dr. Flaubert Sena technique(Figure 3), using a nasogastric tube, antimicrobial incise drape, and gauze. The negative pressure was constant at 125 mmHg. The nasoenteral feeding tube was placed through the alimentary limb(Figure 4), and enteral feeding was initiated 12 h postoperatively. The endoscopic vacuum system was removed on postoperative day 3, without adverse events or symptoms.

The peripancreatic abdominal drain was removed on postoperative day 5, and the amylases were measured. The patient was discharged 5 d after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Figure 1 Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography demonstrated a circumferential tumor of the middle bile duct with upstream biliary dilatation, cholangitis and cholelithiasis. Magnetic Resonance Imaging showing gallbladder invasion.

Figure 2 Surgical specimen following pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Figure 3 Endoscopic vacuum system.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

At the time of drafting this manuscript, the patient was being followed up in the outpatient clinic and had developed no complications related to the procedure. The Oncology Group opted for no adjuvant therapy.

Figure 4 Endoscopic vacuum system placed through the right nostril and the nasoenteral feeding tube placed through the left nostril.

DISCUSSION

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a technically demanding operation, with morbidity rates of approximately 40%–50%. The mortality rate is around 2.6%, and 37%–43% of deaths are directly linked to pancreatic fistulas. However, the prevention of this complication remains challenging, being related to non-modifiable factors (patient’s age, comorbidities, pancreatic texture, and pancreatic duct size) and modifiable variables (anastomosis technique, somatostatin analogs, bleeding, and massive blood transfusions). These variables influence the development of leaks and pancreatic fistulas.

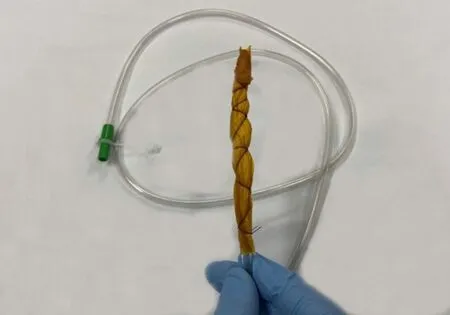

Although cavity drainage is unlikely to influence the rate of these adverse events,we proposed the use of an endoscopic vacuum system to prevent pancreatic fistulas. The system is feasible and effective for the treatment of transmural defects. Tools for building the system include a nasogastric tube (14 Fr), gauze, an antimicrobial incise drape, and a nylon suture. The first step is to make several holes in the nasogastric tube and cut the antimicrobial incise drape to match the size of the fenestrated portion. Subsequently, using an 18-G needle, several holes are made in the antimicrobial incise drape. The next step is wrapping the fenestrated portion of the nasogastric tube using gauze and then with an antimicrobial incise drape. Finally, a 2.0 nylon suture is used to fix the gauze and antimicrobial incise drape at the nasogastric tube (Figure 5). Polyvinyl alcohol foam and polyurethane foam are alternatives for making the system. However, gauze is just as safe and effective as these materials, and is less expensive.

Similar to the therapeutic vacuum, the endoscopic preemptive vacuum may also promote continuous exudate evacuation, reduction of inflammatory edema,improvement of blood supply, and lymphatic drainage. The negative pressure also promotes microdeformation and macrodeformation, leading to angiogenic factors that increase local healing.

Liuproposed that the increased pressure in anastomosis associated with pancreatic enzymes (proteases and phosphatases) could lead to increased leakage in non-hermetic anastomoses due to self-digestion of the anastomosis, and a negative pressure could prevent this process. Therefore, we believe that the endoscopic vacuum system decreases pressure in the biliopancreatic limb and reduces contact between the anastomosis and pancreatic juice. Thus, the preemptive vacuum can prevent leaks and pancreatic fistulas.

In a systematic review of 60739 patients, Sergio Pedrazzolisupported this theory,stating that for fluid flow from one lumen to another, there must be a pressure differential between the means to overcome gravity and peristaltic activity. However,at present, these pressures are not documented. Furthermore, the use of endoluminal drains would favor the removal of biliopancreatic secretions and could be used for the infusion of protease inhibitors.

With regard to complications, a recent systematic review with a meta-analysis published by do Monte Juniordemonstrated bleeding, stricture, and difficulty in removal as the main adverse events. Difficulty in removing the system only occurred in one patient. Considering that the preemptive vacuum therapy system remains in the anastomosis for no longer than 3 d, and the novel system has no sponge, the risk of those complications is small, although they may still exist.Neumannperformed preemptive vacuum therapy for the treatment of anastomotic ischemia after esophageal resection. Using a continuous suction of 125 mmHg, complete mucosal recovery was achieved in 75% of cases. Thus, ischemia caused by this regimen of negative pressure is improbable.

Figure 5 Modified endoscopic vacuum system (distal part).

To diagnose pancreatic fistulas, we used the criteria of the International Pancreatic Fistula Study Group modified in 2016. Our patient had several risk factors for the development of this complication, such as age, malignancy, fat-substituted pancreas,pancreatic duct size < 3 mm, intraoperative transfusion, and preoperative malnutrition. Nevertheless, there were no complications during her evolution. An early oral diet was initiated on postoperative day 2 when peristaltic movements returned.

Various techniques are used to minimize the risk of anastomosis dehiscence,including the application of a fibrin sealant or a fibrin glue-coated collagen patch. The first advantage of preemptive vacuum therapy is that it allows enteral feeding while reducing the risk of leak and fistulas. Compared with the modified vacuum system, a preemptive vacuum is a feasible and cost-effective method for preventing those circumstances. Aside from this, recent studies demonstrated that fibrin sealant patches had no significant effect on the rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula.

CONCLUSION

Preemptive endoluminal vacuum therapy might be a safe and feasible technique to reduce leaks after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Yuri Raoni, Department of Radiology, Heart Hospital, for providing magnetic resonance imaging findings.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy的其它文章

- Anticoagulation and antiplatelet management in gastrointestinal endoscopy: A review of current evidence

- Peroral traction-assisted natural orifice trans-anal flexible endoscopic rectosigmoidectomy followed by intracorporeal colorectal anastomosis in a live porcine model

- Evaluation of the diagnostic and therapeutic utility of retrograde through-the-scope balloon enteroscopy and single-balloon enteroscopy

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug effectivity in preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage in pancreatic cancer and cholangitis: A case report

- Curling ulcer in the setting of severe sunburn: A case report