Diagnostic accuracy of administrative database for bile duct cancer by ICD-10 code in a tertiary institute in Korea

2021-01-07YoungJeHwngSeonMeePrkSoominAhnJonghnLeeYoungSooPrkNyoungKim

Young-Je Hwng , Seon Mee Prk , Soomin Ahn , Jonghn Lee , Young Soo Prk ,Nyoung Kim , d, e,*

a Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

b Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine and Medical Research Institute, Cheongju, Korea

c Department of Pathology, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoungnam, Korea

d Department of Internal Medicine and Institute of Liver Research, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

e Tumor Microenvironment Global Core Research Center, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

Keywords:National Health Insurance Service Bile duct cancer ICD-10

A B S T R A C T Background: Administrative database provides valuable information for large cohort studies, especially when tissue diagnosis is rather difficult such as the diagnosis for bile duct cancer (BDC). The aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of administrative database for BDC by International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes in a tertiary institute.Methods: BDC and control groups were collected from 2003 to 2016 at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. Cases of BDC were identified in the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database by ICD 10-code supported by V code. The control group was selected from cases without ICD-10 codes for BDC.A definite or possible diagnosis was defined according to pathologic reports. Medical records, images,and pathology reports were analyzed to evaluate ICD-10 codes for BDC. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for BDC were analyzed according to diagnostic criteria and cancer locations.Results: A total of 1707 patients with BDC and 1707 controls were collected. Among those with BDC,1320 (77.3%) were diagnosed by definite criteria. Most (99.4%) of them had adenocarcinoma. Rate of definite diagnosis was the highest for ampulla of Vater (88.9%), followed by that for extrahepatic (84.9%) and intrahepatic (68.3%) BDCs. False positive cases commonly had hepatocellular carcinomas. For overall diagnosis of BDC, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were 99.94%,98.33%, 98.30%, and 99.94%, respectively. Diagnostic accuracies were similar regardless of diagnostic criteria or tumor locations.Conclusions: Administrative database for BDC collected according to ICD-10 code with V code shows good accuracy.

Introduction

Bile duct cancer (BDC) is more prevalent in Asian countries,including China, Vietnam, and Korea, than that in Western countries [1] . The incidence of BDC has increased in recent years.It is the 6th most common cause of cancer-related mortality in Korea [2] . However, its risk factors and prognostic factors remain unclear [3] . To examine risk factors and long-term prognoses of BDC, several population-based studies have been performed using administrative databases [4-9] . In Korea, data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database can provide useful information about patients diagnosed by the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision edition codes (ICD-10 code)[4] . It covers the entire Korean population by including more than 50 0 0 0 0 0 0. However, the purpose of administrative databases is to collect data for reimbursement, not for clinical care. In addition,their accuracy for identifying cancer patient remains doubtful [10] .To avoid coding discrepancies, the administrative database needs to have the accuracy of diagnosis validated [10] . However, there are not enough reports about the validity of administrative database in Korea. In addition, it is difficult to study with various institutes.Recently we have published the validation of ICD-10 code in colorectal cancer [11] . Similarly, the aim of this study was to evaluate the value of the administrative database for BDC in a single institute. To that end, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value(PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for the diagnosis of BDC by ICD-10 code were calculated and compared to those of controls.Our results will support studies using administrative data and provide proper methods for selecting patients with BDC among administrative databases.

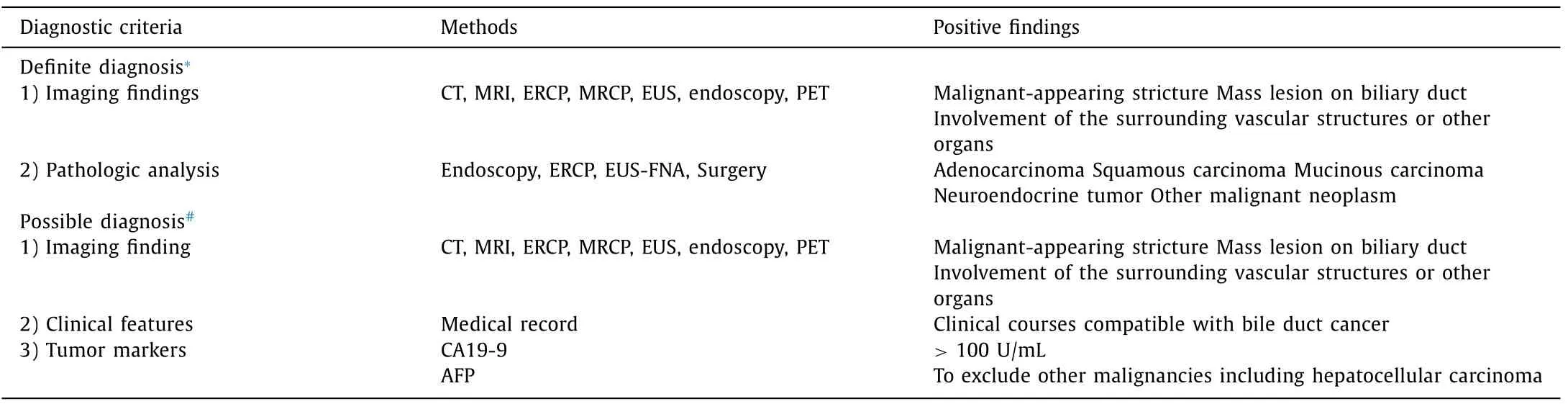

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria of bile duct cancer.

Methods

Data sources

Patients with BDC and controls were collected using Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH) Clinical Data Warehouse (CDW) from May 1, 2003 to December 31, 2016 [12] . Patients with BDC were identified in the administrative database by ICD-10 codes. Medical records were searched using SNUBH’s CDW [12] , the hospital’s own database analysis program. Electronic medical record (EMR) system contained information about visiting departments, principal diagnosis, diagnostic procedures,and treatments for each patient. It also included pathologic data and imaging modalities, including endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP),and positron emission tomography (PET) [3 , 13-15] .

Study population

After obtaining approval of our study protocol from the Ethics Committee at SNUBH (IRB number: B-1701/378-105), a list of patients with BDC were requested from the CDW using the following ICD-10 codes as primary diagnosis: C22.1 (intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma), C24.0 (malignant neoplasm of extrahepatic bile duct),C24.1 (malignant neoplasm of ampulla of Vater [AOV]), C24.8 (malignant neoplasm of overlapping lesion of biliary tract), and C24.9(malignant neoplasm of biliary tract, unspecified) [16] . These patients were then identified by their registered V code, a specific coding system to confirm cancer patients with ICD-10 codes in the NHIS database in Korea [4] . Controls were selected from cases who visited SNUBH with diagnoses of diseases other than C22.0 - 22.9 or C24.0 - 24.9 during the study period.

Diagnosis criteria of bile duct cancer

Medical records of BDC and control groups were analyzed. Information about dates and departments of hospital visits, demographics, diagnostic procedures, pathologic results, and surgery was obtained through the EMR. Other hospital medical data were also identified through uploaded databases in SNUBH. Because BDC is difficult to accurately diagnose, evaluation of administrative coding data for BDC is more important than what for other diseases. Tissue sampling for pathologic diagnosis of BDC is sometimes impossible [17 , 18] . In addition, the diagnosis of primary cancer sites is difficult if BDCs have infiltrated to other organs. Therefore, BDCs are diagnosed by pathologic findings. Sometimes they are diagnoses by clinical, laboratory, endoscopic, and radiologic features [3] . Each patient was analyzed for definite and possible criteria of BDC diagnosis ( Table 1 ) [3 , 14 , 15] . Patients showing both typical imaging features and pathologic evidence of BDC belonged to the definite diagnosis group [18] . Pathologic diagnoses of BDCs were classified as adenocarcinoma, squamous carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, and neuroendocrine tumors [14 , 18] . Pathologic specimens were obtained from the bile duct or metastatic organs by surgery, diagnostic laparoscopy, duodenoscopy, ERCP, or EUS-fine needle aspiration (FNA). Patients with typical imaging findings and clinical features of BDC in the absence of pathologic diagnosis belonged to the possible diagnosis group. Typical imaging features of BDC were defined as malignant-appearing strictures, mass lesions on the bile duct, and involvement of the surrounding vascular structures or other organs on CT, MRI, ERCP, MRCP, EUS, endoscopy, or PET [19] . Clinical features for BDC were defined as progression of clinical course or elevated serum levels of carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 (>100 U/mL) in the absence ofα-fetoprotein elevation [19 , 20] .

Evaluation for diagnostic accuracy of bile duct cancer diagnosis

Medical records were examined to validate the true or false status of the ICD-10 code for BDC. To enhance reviewing accuracy,three reviewers carefully examined medical records and compared the final diagnosis for each patient. For discordant conclusions,they discussed those cases until they reached a concordant diagnosis. After reviewing medical records and classifying each case,sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were calculated for total, definite, and possible diagnostic criteria of BDC. Diagnostic power was also compared according to the following cancer sites: intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC, C22.1), extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma(ECC, C24.0), and ampulla of Vater cancer (AVC, C24.1).

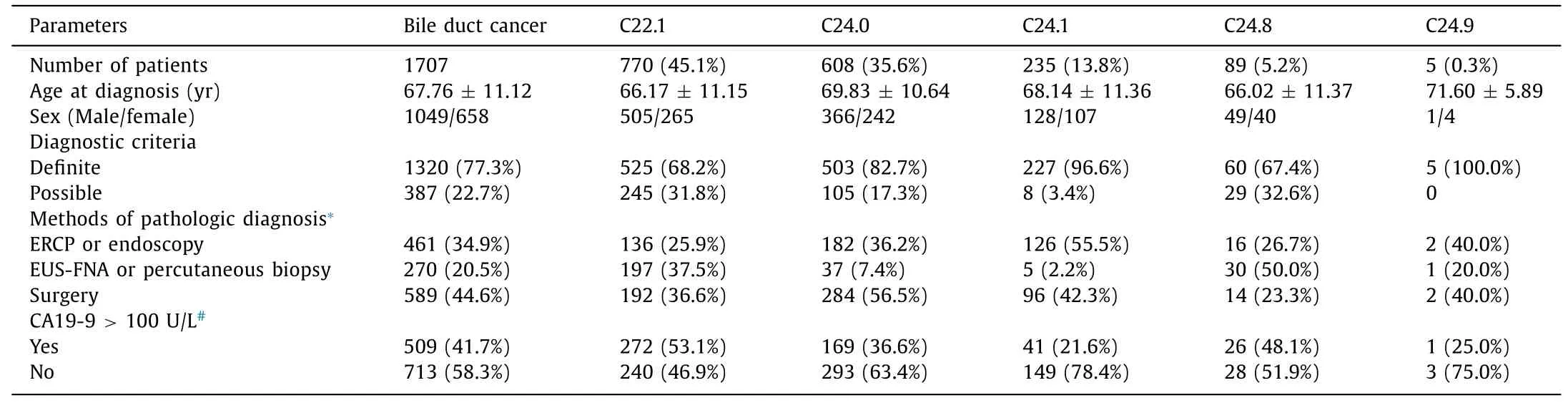

Table 2 Characteristics of patients with bile duct cancer according to ICD-10 codes.

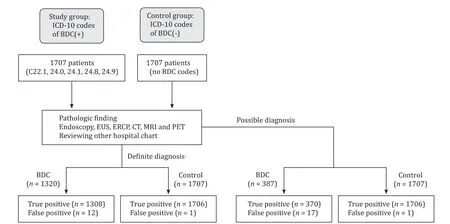

Fig. 1. Proposed study algorithm for the inclusion and classification of subjects. BDC, bile duct cancer; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; CT, computerized tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography.

Statistical analysis

After reviewing the chart and grouping of each subject, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were calculated. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. In addition, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using SPSS version 20.0 for Windows(SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Significance level was set atP<0.05.

Results

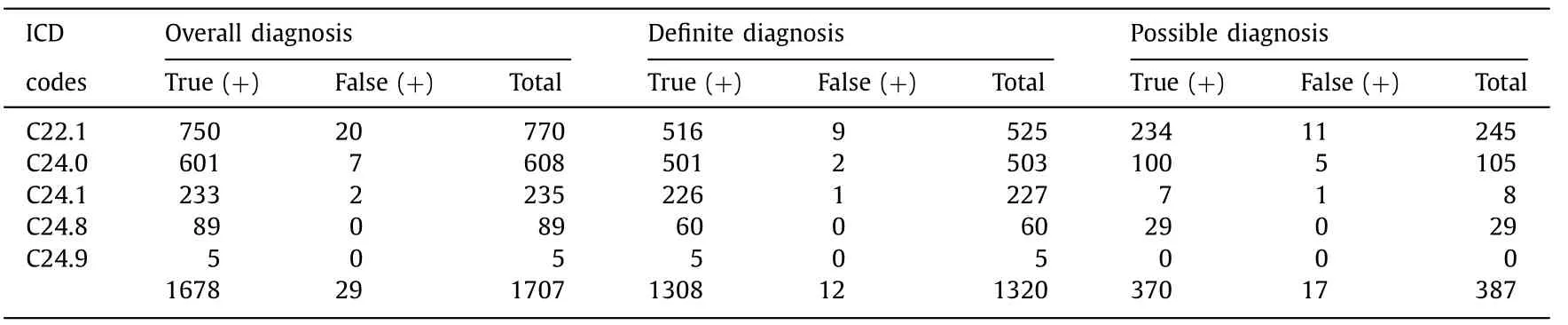

Characteristics of bile duct cancer patients by ICD-10 codes

A total of 1707 patients were identified by ICD-10 codes as having BDC at SNUBH during the study period ( Table 2 , Fig. 1 ). Among BDCs, ICC was the most common one [770 (45.1%) patients], followed by ECC [608 (35.6%) patients] and AVC [235 (13.8%) patients]. The number of patients with unclear cancer sites, such as overlapping (C24.8) and unspecified (C24.9) sites were 89 (5.2%)and 5 (0.3%), respectively. Among patients with BDCs, 1320 (77.3%)patients fulfilled the definite diagnostic criteria while 387 (22.7%)patients met the possible diagnostic criteria. Pathologic diagnosis was performed by surgery in 589 (44.6%) patients, ERCP or endoscopy in 461 (34.9%) patients, and EUS-FNA or percutaneous biopsy in 270 (20.5%) patients. Among 1222 patients whose serum levels of CA19-9 were checked, 509 (41.7%) patients revealed elevated CA19-9 (>100 U/L).

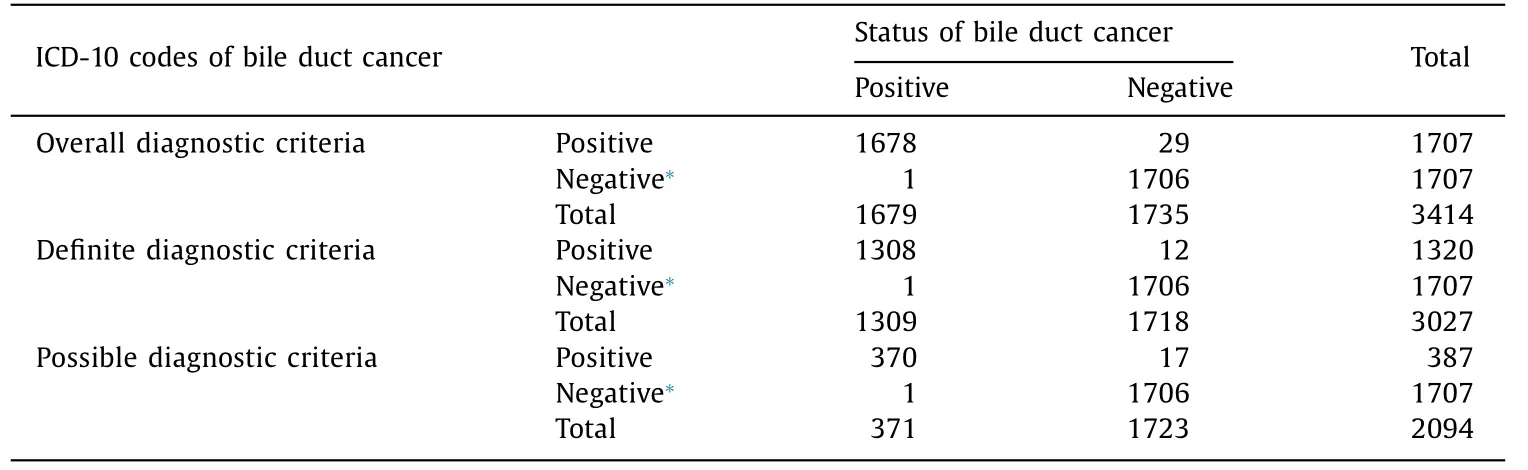

Diagnostic accuracy for bile duct cancer in the administrative database

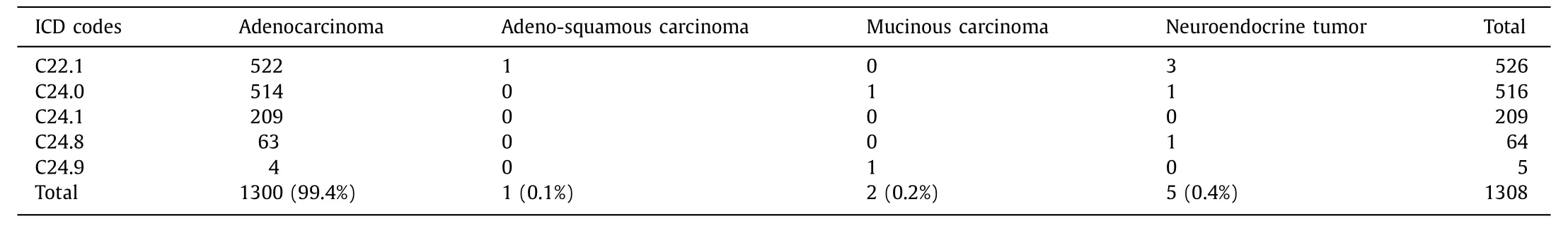

In 1320 patients with definite diagnoses, most [1300 (99.4%)]of them had adenocarcinoma. Other types were diagnosed in 8 patients (neuroendocrine tumor in 5, mucinous carcinoma in 2, and adeno-squamous carcinoma in 1) ( Table 3 ). Twelve patients were identified as having incorrect diagnoses: 9 of these patients hadhepatocellular carcinoma, while chronic cholecystitis, hepatic cysts,and renal cell carcinoma with liver metastasis were found in 1 patient each. In 387 patients with possible diagnoses, 370 satisfied the possible diagnostic criteria for BDC and 17 were identified as incorrect diagnoses (hepatocellular carcinoma in 10 patients, liver metastasis in 4, chronic cholecystitis in 1, and no diagnostic evaluation in SNUBH or other hospitals in 2).

Table 3 Cancer cell types of bile duct cancer.

Table 4 Diagnostic accuracy of bile duct cancer diagnosed by ICD-10 code in the administrative database.

Table 5 Diagnostic accuracy of bile duct cancer according to tumor sites by ICD-10 codes.

We randomly selected 1707 control subjects who had no ICD-10 codes of BDC. Among these cases in the control group, only one patient was a false negative, who received cholecystectomy due to gallbladder wall thickening identified on CT. Pathology revealed adenocarcinoma originating from the bile duct. However, this patient was registered as having gallbladder cancer (C23) ( Table 4 ).

We evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of BDC according to tumor sites ( Table 5 ). Rate of definite diagnosis was the highest in AVC (88.9%), followed by that in ECC (84.9%) and ICC (68.3%).

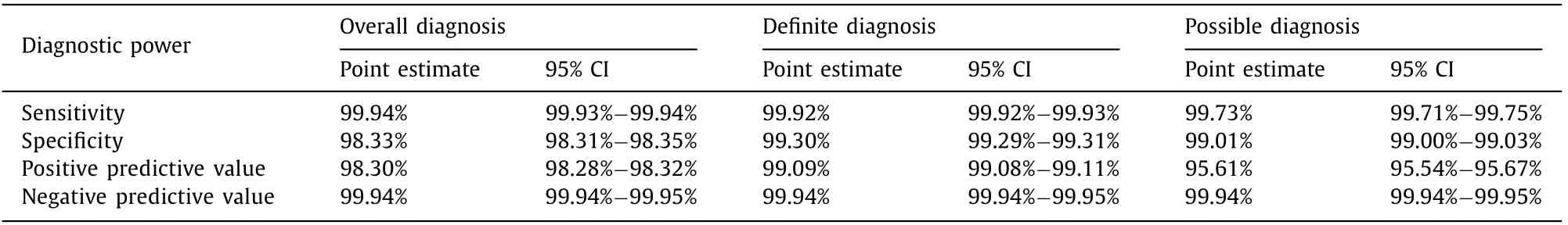

Diagnostic accuracy of ICD-10 codes for bile duct cancer in the administrative database

In overall diagnosis of BDC, sensitivity and specificity of ICD-10 codes were 99.94% (95% CI: 99.93% -99.94%) and 98.33% (95% CI:98.31% -98.35%), respectively ( Table 6 ). PPV and NPV were 98.30%(95% CI: 98.28% -98.32%) and 99.94% (95% CI: 99.94% -99.95%),respectively. For definite diagnostic criteria of BDC, sensitivity and specificity were 99.92% (95% CI: 99.92% -99.93%) and 99.30%(95% CI: 99.29% -99.31%), respectively. PPV and NPV were 99.09%(95% CI: 99.08% -99.11%) and 99.94% (95% CI: 99.94% -99.95%),respectively. For possible diagnostic criteria of BDC, sensitivity and specificity were 99.73% (95% CI: 99.71% -99.75%) and 99.01%(95% CI: 99.00% -99.03%), respectively. PPV and NPV were 95.61%(95% CI: 95.54% -95.67%) and 99.94% (95% CI: 99.94% -99.95%),respectively.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that diagnostic accuracy of administrative database for BDC by ICD-10 code, supported by V code in the NHIS database, was very high. Our results also supported the reliability of previous large-cohort studies using administrative databases in Korea [4 , 6 , 9] .

Nowadays, large administrative databases gathered from various disease registries have been used in population-based studies [4 , 6 , 21] . However, most of these studies cited the quality of the database by relying on previous studies instead of on independent evaluation of the database. Utada et al. have studied the incidence and mortality of BDC using four population-based cancer registries in Japan [22] . They suggested that their database was acceptable by citing a previous study [23] without validation.Katanoda et al. have reported the trends of cancer incidence inJapan using population-based cancer registries of five prefectures in Japan [23] . They compared proportions of death certificate notification, microscopic verification, and mortality to incidence ratio with national estimates. Bjerregaard et al. have reported trends of liver, gallbladder, bile duct, and pancreas cancer in elderly populations using the NORDCAN database in Denmark [24] . The accuracy of the database was supported by its use in a previous study [25] . Another method to support the validity of their database was by demonstrating similar trends to those of national estimates. Several studies have evaluated administrative database. However, these studies were limited to pancreatic neoplasm by ICD-9 codes [10-26] . or they included small number of cases [27] . These studies suggested that evaluation of the administrative database is essential for large-cohort studies and that ICD codes alone are insufficient to identify patients [22-25] . Other information should be added to the principal ICD codes to improve PPV for the identification of cancer patients [28] .

Table 6 Diagnostic power of ICD-10 codes for bile duct cancer.

In recent years, several population based cancer studies using the NHIS database have been reported [4 , 5 , 9 , 10] . However, studies on the validity of the NHIS database for cancer diagnosis in Korea have not been reported yet. Some people thought that almost registered cases were truly disease cases. However, we thought that administrative database could not be trusted without research for identifying validity of database. Thus, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the ICD-10 codes for BDC in NHIS. BDC is focused in this study because it is a challenging disease mainly due to its difficulty of biopsy. We used two disease registries, the SNUBH database and the NHIS database, to identify BDC patients and controls. We analyzed diagnostic accuracy according to definite diagnostic criteria and possible diagnostic criteria. Despite difficulty in obtaining specimens from the biliary tree, 77% of patients received a pathologic diagnosis. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV achieved high levels for both definite and possible diagnostic criteria. We compared these diagnostic criteria according to tumor sites. As expected, the rate of pathologic diagnosis was the highest for AVC (88.9%), followed by that for ECC (84.9%) and ICC (68.3%).Because AVC can be easily obtained from pathology specimens by endoscopic biopsy, pathologic diagnosis is easier than that for other sites of BDC. In this study, analyzing false positives demonstrated that in 9 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma it was difficult to differentiate from ICC. False-negative was very rare in this study.

Each institute has its own medical database system, making it difficult to integrate various institutes databases. When collecting database from various institutes, it is useful to collect data from national disease registries like NHIS. To validate NHIS, we selected BDC patients based on both ICD-10 codes and the V code of NHIS. The Korean government has launched a Support for Serious Illness program, in which the coinsurance rate is reduced for registered cancer patients. Registration in the program requires a physician’s diagnosis which necessitates confirmation by more than one pathological result, typical radiologic finding, or laboratory data. Cancer diagnosis is further reviewed by another healthcare professional to ensure that it meets the diagnostic criteria. After this process of inserting V code by doctors and signing this document by cancer patients, BDC patients were able to receive support. Therefore, the diagnostic accuracy would be increased by adding V code to ICD-10 code because subjects were checked twice by SNUBH and NHIS. Without the V code system, confirmation of cancer patients and collection of study subjects would be difficult. It needs to be carefully performed as shown in previous studies [10-26] . This NHIS database which also collects V code is very useful. Some reports have been generated from NHIS resources in Korea [4 , 29 , 30] . In addition, surgical management is the only curative treatment available for BDC. However, many patients present with unresectable tumors are needed for large cohort study to evaluate high risk patients and screening test [31] .Thus, diagnostic accuracy of large cohort database should be evaluated.

Initially we tried to collect database from various institutes.However, it was difficult because of different medical chart systems. Finally, we performed our study in a single institute, SNUBH.It is considered appropriate for this study because of its comprehensive EMR system [12] . SNUBH has developed an in-house comprehensive EMR since 2003. The warehouse system provides easy access to patient’s diagnostic information for research [12 , 32] . In addition, SNUBH is a tertiary hospital to which regional hospitals can refer patients. Therefore, sufficient numbers of BDC patients were enrolled in this study to enhance the power of evaluation results. To satisfy statistical requirements (α= 0.05, 1-β= 0.95, and effect size of 0.1), more than one thousand patients were needed.The size of our study group was enough to fulfill these statistical criteria. Our study has significance because it contains a large cohort with manual analysis.

Our study has several limitations. First, although one-quarter of patients were diagnosed by possible diagnostic criteria, they were finally diagnosed as BDC by clinical progression with typical features of imaging findings and tumor markers. Because most patients with BDC were diagnosed in advanced stages with poor clinical course, pathologic diagnosis was sometimes impossible. Therefore, if we only adopt definite diagnostic criteria for BDC evaluation, selection bias could occur. Another weak point of this study was that it was performed in a tertiary hospital, SNUBH. The diagnostic accuracy might be higher in referral tertiary hospitals compared to multicenter studies. We supposed that most BDC patients were treated in a referral hospital in Korea. Despite this limitation,BDC data in the SNUBH selected by ICD-10 could be acceptable for population-based large-cohort studies.

In conclusion, ICD-10 codes for BDC in the administrative database might be acceptable for use in population-based largecohort studies. This study method identifies information regarding tumor location in relation to AOV and histology of BDC.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Young-Jae Hwang:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing -original draft.Seon Mee Park:Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.Soomin Ahn:Validation, Visualization.Jongchan Lee:Writing - review & editing.Young Soo Park:Writing - review & editing.Nayoung Kim:Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (No. 2011-0 030 0 01 ) for the Global Core Research Center (GCRC) funded by the Korean government (MSIP).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (B-1701-378-105).

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Non-operative management of pancreatic trauma in adults

- Serum non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level is increased in Chinese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Increased CMTM4 mRNA expression predicts a poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

- Folfirinox chemotherapy prolongs stent patency in patients with malignant biliary obstruction due to unresectable pancreatic cancer

- Role of phosphorylated Smad3 signal components in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of pancreas ✩

- Long noncoding RNA HAND2-AS1 re duce d the viability of hepatocellular carcinoma via targeting microRNA-300/SOCS5 axis