Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence post direct-acting antivirals in hepatitis C-related advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis patients in Australia

2021-01-07PatrickChanMiriamLevyNicholasShackelScottDavisonEmiliaPrakoso

Patrick P Y Chan , Miriam T Levy , Nicholas Shackel , Scott A Davison ,Emilia Prakoso

a Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Liverpool Hospital, Elizabeth Street, Liverpool, NSW 2170, Australia

b South Western Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Liverpool, NSW 2170, Australia

c Central Clinical School - The Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, NSW 2050, Australia

Keywords:Direct-acting antiviral Cirrhosis Hepatitis-C virus Hepatocellular carcinoma Recurrence

A B S T R A C T Background: Despite efficacy in HCV eradication, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy has raised controversies around their impact on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence. Herein we reported the first Australian data on HCC incidence in DAA-treated HCV patients with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis.Methods: We conducted a retrospective single center study of DAA-treated HCV patients with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis from April 2015 to December 2017. Patients with prior HCC were included if they had complete response to HCC treatment.Results: Among 138 patients who completed DAA therapy, 133 (96.4%) achieved sustained virologic response (median follow-up 23.8 months). Ten had prior HCC and 5/10 (50.0%) developed recurrence, while de novo HCC developed in 7/128 (5.5%). Median time from DAA to HCC diagnosis was 34 weeks in recurrent HCC vs. de novo 52 weeks ( P = 0.159) . In patients with prior HCC, those with recurrence (vs. without)had shorter median time between last HCC treatment and DAA (12 vs. 164 weeks, P < 0.001). On bivariate analysis, failed sustained virologic response at 12 weeks (SVR12) ( P = 0.011), platelets ( P = 0.005), model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score ( P = 0.029), alpha fetoprotein (AFP) ( P = 0.013), and prior HCC( P < 0.001) were associated with HCC post-DAA. On multivariate analysis, significant factors were prior HCC (OR = 4.80; 95% CI: 1.47-48.50; P = 0.010), failed SVR12 (OR = 2.83; 95% CI: 1.71-16.30; P = 0.016)and platelets (OR = 0.97; 95% CI: 0.95-0.99; P = 0.009).Conclusions: Our study demonstrates a high incidence of recurrent HCC in HCV patients with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis treated with DAA. Factors associated with HCC development post-DAA were more advanced liver disease, failed SVR12 and prior HCC, with higher rates of recurrence in those who started DAA earlier.

Introduction

The burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) is estimated to affect 71 million people in 2015 worldwide, accounting for approximately 40 0 0 0 0 deaths due to cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma(HCC) [1] . The advent of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy has changed the landscape of HCV treatment due to their high rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) in combination with its safety profile in comparison to interferon-based predecessors [2] . The potential of DAA to eradicate hepatitis C prompted the Australian government to invest A$ 1 billion in 2016 towards subsidizing DAA therapy for all hepatitis C-infected patients in alignment with the World Health Organization’s goal of eliminating hepatitis C by 2030 [3] . Over 74 600 individuals in Australia are estimated to have initiated DAA therapy for hepatitis C [4] .

In 2016, Reig et al. [5] reported a high incidence and earlier recurrence of HCC in a Spanish cohort following DAA therapy. Since then, a number of conflicting studies have been published that suggest either increased HCC incidence (eitherdenovoor recurrence) [5-8] , or no difference in DAA-treated patients [9-13] , causing considerable concern and controversy. Waziry et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 41 studies of HCC occurrence/recurrence in both interferon and DAA treated patients and showed no difference between the two groups [14] . The at-risk group appears to be those individuals with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis and therefore it is important to identify factors associated with HCC post-DAA to guide better patient selection. The 2018 European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines for HCV treatment acknowledge these conflicting studies and recommend DAA treatment to achieve SVR12 and reduce the risk of HCC [15] .

Herein we reported the first real world Australian data for HCC incidence in at-risk patients with hepatitis C post-DAA treatment and the patient characteristics.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a single center retrospective analysis of adult patients with HCV-related advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis who were treated with DAA between April 2015 and December 2017. We used a protocol driven system that guides and records management from initial referral to assessment and surveillance for all patients commenced on DAA therapy in our hepatology service. Of these patients, those included in this study met the following selection criteria: 1) patient age older than 18 years; 2) elastographybased diagnosis of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis (defined as>9.5 kPa [16] ); 3) completed DAA therapy (including those with previous interferon-based treatments); and 4) liver imaging prior to DAA therapy, within 3 months for those with history of HCC,and within 6 months for those without history of HCC. Patients with HCC were diagnosed according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease diagnostic algorithm [17] . Of patients with prior HCC, we only recruited those with evidence of complete response (CR). This was defined as disappearance of intratumoral arterial enhancement in target regions [17]. CR could have been achieved by surgical resection, transarterial chemoembolization, and radiofrequency or microwave ablation. Patients were excluded if 1) they had incomplete radiological response (residual intratumoral arterial enhancement in target lesions); 2) indeterminate nodules [17] within three months prior to DAA initiation;3) or if they were treated with systemic palliative therapies such as sorafenib. In our institution, patients with a history of HCC underwent 3-monthly surveillance [through paired multiphase CT or MRI, and serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) measurements] whilst cirrhotic patients without a history of HCC were monitored through 6-monthly paired liver ultrasound and serum AFP.

Data collection and analysis

Baseline demographics (age and sex) and laboratory tests(liver function tests, platelet, and AFP), and HCV genotypes were recorded prior to DAA initiation. Child-Pugh and MELD scores were calculated for each patient at the time of DAA initiation as an indicator of baseline liver disease severity. For each patient, the DAA treatment regimen was recorded and the time interval was measured between: 1) the date of last HCC treatment and the date of DAA initiation; and 2) the time between DAA initiation and the diagnosis of HCC recurrence ordenovooccurrence. Treatment outcome was defined as SVR12, indicated by the absence of serum HCV RNA on a sensitive polymerase chain reaction assay at 12 weeks after completion of DAA [15] .

We pooled together bothdenovoand recurrent HCC patients and compared this group to those who did not develop HCC at the end of the follow-up period. We calculated the annual incidence of HCC in our cohort using two time points, the date of DAA initiation and the last follow-up date prior to December 31, 2018.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median(range) or number (percentage). Bivariate analysis was performed between the comparison groups. Chi-square test was for categorical data, the Student’st-test or Mann-WhitneyUtest was for continuous variable where appropriate. Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression to identify the variables that were independently associated with the development of HCC. Factors included in the model consisted of significant associations identified in the bivariable tests described above, as well as age and sex.All independent variables were entered in one single step without stepwise selection. The logistic regression model was assessed using an omnibus (Chi-square) test and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.All statistical tests were two-sided and statistical significance was defined as aPvalue<0.05. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS Statistics, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY,USA).

Results

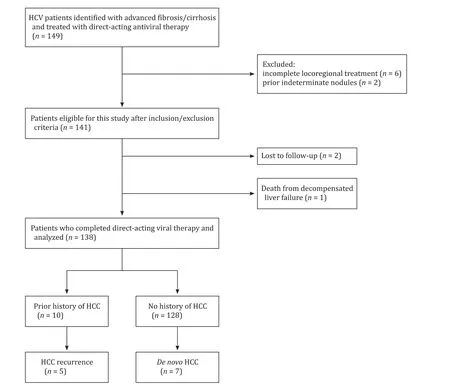

A total of 149 patients who commenced on DAA therapy were initially identified for this study ( Fig. 1 ). Six patients with prior HCC were excluded because of incomplete radiological response whilst 2 patients had indeterminate nodules prior to DAA therapy. Among 141 patients included in the study, one died from decompensated liver failure and two were lost to follow up. Of the remaining patients (n= 138), 133/138 (96.4%) completed their treatment regimen and achieved SVR12. We analyzed a total of 246.2 patient-years with a median follow-up time of 23.8 months(5.5-43.6 months). Given 12 HCC patients (5 recurrence and 7de novo), there was an overall annual HCC incidence rate of 4.87/100 patient-years, and 3.13/100 patient-years in thedenovogroup only.

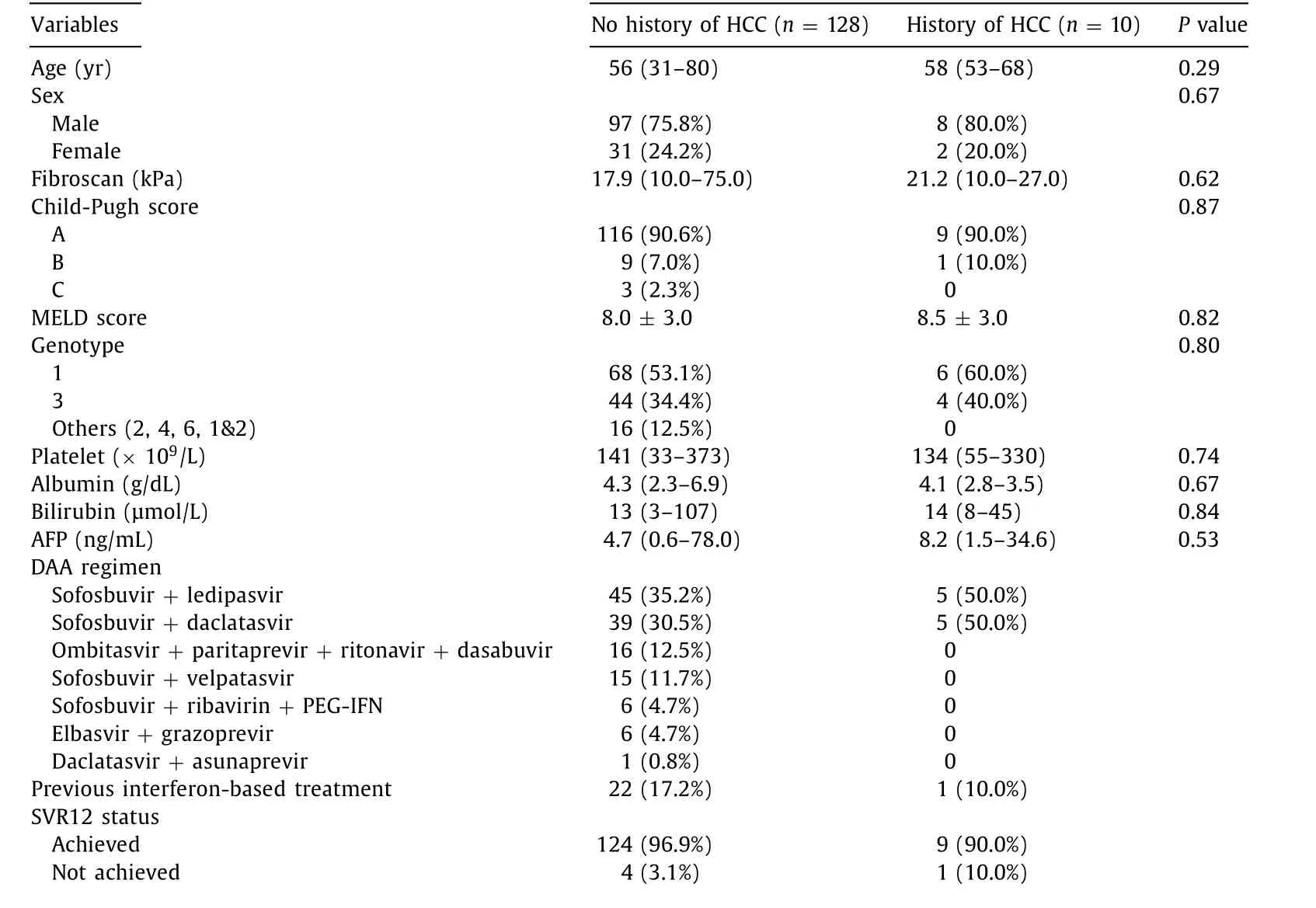

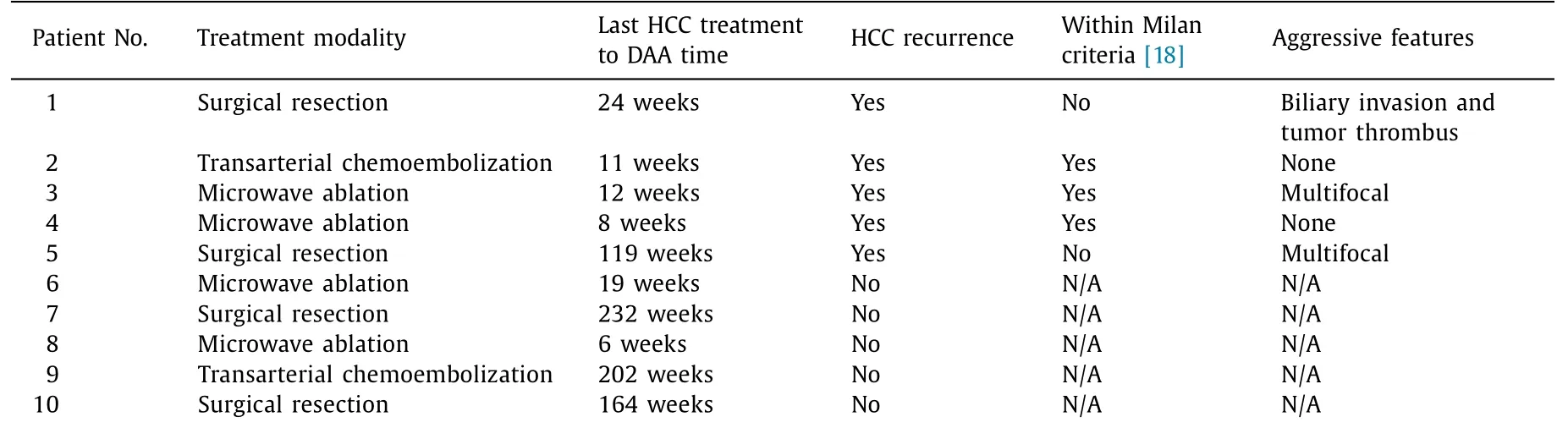

Between patients who had a prior history of HCC and those without, there was no statistical difference in their baseline characteristics ( Table 1 ). Ten (7.3%) patients with prior HCC had CR based on multi-phase CT or MRI prior to DAA therapy. Four patients of them were managed surgically whilst six patients had locoregional treatment ( Table 2). Five (50.0%) developed HCC recurrence, 2 of whom underwent surgical resection whilst the other 3 had locoregional treatment prior to recurrence. Three (60.0%) of the HCC recurrences exhibited aggressive characteristics with either multifocal disease or vascular/biliary associated invasion ( Table 2 ). The median time from the last HCC treatment to DAA initiation was 12 weeks (8, 11, 12, 24 and 119 weeks for the individual patients) in those with recurrent HCC ( Fig. 2 ), compared to 164 weeks in those without recurrence (P<0.001).

Seven (7/128, 5.5%)denovoHCC patients were diagnosed post-DAA therapy. Four (57.1%) of them demonstrated aggressive characteristics compared to three (60.0%) within the group who developed HCC recurrence (P= 0.797). The median time between initiation of DAA therapy to HCC diagnosis was 52 weeks in those who developeddenovoHCC, whilst those with HCC recurrence had a median time to diagnosis of 34 weeks (P= 0.159).In a post-hoc subgroup analysis to assess if those who were treated with DAAs within 6 months from their last HCC treatment had a higher recurrence rate compared to those treated after 6 months, the result was not statistically significant (P= 0.197).

On analysis of pooled patients who developed HCC post-DAA( Table 3 ), baseline lower platelet count (P= 0.005), higher AFP(P= 0.013), higher model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score(P= 0.029), failure to achieve SVR12 (P= 0.011) and a prior history of HCC (P<0.001) at the time of DAA initiation were all found to be associated with HCC development post-DAA (denovoor recurrence). A multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusting for age and significant bivariate factors demonstrated that lower platelet count (OR = 0.97; 95% CI: 0.95-0.99;P= 0.009), failure to achieve SVR12 (OR = 2.83; 95% CI: 1.71-16.30;P= 0.016) and prior history of HCC (OR = 4.80; 95% CI: 1.47-48.50;P= 0.010) predicted an increased risk of HCC. The omnibus test of the model coefficient was significant (χ2= 21.04,P= 0.002) and the “goodness-of-fit” was adequate (χ2= 4.96,P= 0.762).

Fig. 1. Flowchart of patients selection for the study. HCV: hepatitis C virus; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

Fig. 2. Median time between last hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treatment, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy and HCC detection.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of HCV patients with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis who completed direct-acting antiviral therapy ( n = 138).

Table 2 Individual treatment and tumor factors in patients with prior hepatocellular carcinoma.

Table 3 Bivariate and multivariate analysis of patient characteristics comparing those who developed hepatocellular carcinoma (both recurrence and de novo ) post direct-acting antiviral therapy and those without.

Discussion

The introduction of DAA therapy in the recent decade has impacted greatly on hepatitis C management. Overall, there is a significant net reduction in HCC risk with DAA therapy [ 9 , 13 , 19 ], but the risk in patients with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis remains unclear. This study described the characteristics of an Australian cohort with HCV-associated advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis treated with DAA and the incidence of HCC within this at-risk group.

Our study demonstrated a high incidence of HCC recurrence(50.0%), whilstdenovoHCC incidence (5.5%, 3.13/100 patient-years)falls within the range described in the literature (1% -7%) [20] .Baseline platelet count and MELD score demonstrated a statistically significant correlation with the development of HCC post-DAA in our cohort. These findings support the notion that, rather than DAA therapy being directly implicated in the reported increases in HCC incidence/recurrence, the severity of the underlying liver disease may drive the higher rates of HCC. The transition from interferon-based therapy to the more well-tolerated DAAs allows a wider cohort of patients, including those with more advanced liver disease to be treated [21] . These findings would support earlier treatment of patients with HCV infection as delayed HCV clearance may result in progression of cirrhosis and potentially increase the risk of HCC, downstream morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs.

A small subset of patients failed to achieve SVR12 following DAA (5/138). Despite the small numbers, these patients were found to have a greater than 2-fold risk of developing HCC compared to those who attained SVR12, even after multivariate adjustment for significant factors associated with HCC (OR = 2.83; 95% CI:1.71-16.30;P= 0.016).These findings are consistent with another study [22] .

Further controversy regarding HCC risk surrounds the possibility of accelerated and more aggressive carcinogenesis following DAA treatment. In our study, although the median time from DAA initiation to HCC diagnosis was shorter in those with HCC recurrence compared to those withdenovoHCC (34 vs. 52 weeks),which did not reach statistical significance (P= 0.159). Historically,the median time to recurrence following last HCC treatment reported in the literature varied from 8 to 15 months [23-25] , of which our data were on the lower range. Several studies have identified early occurrence/recurrence of HCC following DAA therapy[ 5 , 6 ], whilst others have attributed early recurrence to confounding factors, including history of HCC recurrence [ 26 , 27 ] and tumor size[26] . Whilst we have excluded patients with indeterminate nodules prior DAA initiation and all patients followed rigorous protocol for HCC surveillance, the high incidence of HCC recurrence within the first year post-DAA may suggest occult HCC. Furthermore, prior HCC (P= 0.010) and baseline platelet (P= 0.009) were significantly associated with HCC development in our study. The main limitation in understanding whether or not there is a true impact of DAA therapy on carcinogenesis rate is the lack of an ideal control group and the variety of patients, prior HCC characteristics and treatments being analyzed. The comparison would preferably be conducted in a randomized controlled trial between DAA and placebo treated subjects. Alternatively, Cabibbo et al. [26] used indirect measures by comparing DAA-treated patients to HCC patients with untreated HCV (pooled by meta-analysis) and interferon-treated patients as a benchmark for HCC recurrence rates, acknowledging the cohorts could vary greatly at baseline.

In our study the median time from last HCC treatment to DAA therapy was 12 weeks in patients who had HCC recurrence, compared to 164 weeks indenovoHCC (P<0.001). It is unclear whether delaying therapy would have resulted in reduced HCC recurrence as there may have been insufficient time for residual disease to manifest, whilst those with longer recurrence-free intervals are more likely to be truly cancer-free. This raises the clinical question of the optimal time to commence HCV antiviral treatment in the context of previously treated HCC. As the HCC recurrence alters HCV management strategy and timing, further studies investigating predictive factors for HCC recurrence would aid in risk stratifying candidates for DAA therapy.

The key limitation of this study pertains to its relatively small cohort size as a single center study, potentially affecting how generalizable it is to population in other centers and countries. Our findings however report the first published Australian data and are consistent with emerging results from other countries [22] . Similar studies that have been previously published have also lacked an adequate control group. We did not include patients who only received interferon-based treatments, or untreated HCV patients retrospectively as a control due to differences in baseline characteristics that would have introduced significant bias to the results.

In conclusion, we described the first real world Australian cohort of patients with HCV-related advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis who were treated with DAA therapy in relation to the development of HCC. Our cohort demonstrated an HCC recurrence rate of 50.0%in those with prior HCC,denovoHCC incidence rate of 5.5%(3.13/100 person-years), and an overall annual HCC incidence rate of 4.87/100 patient-years. The data suggest that the risk of HCC development post-DAA was due to more advanced liver disease,failure to achieve SVR12 and prior HCC. Furthermore, a relatively short interval between HCC treatment and commencing DAA therapy was associated with increased HCC recurrence and additional research into predicting HCC recurrence risk may better aid in optimal patient selection and timing of DAA therapy.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Patrick P Y Chan:Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation,Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Miriam T Levy:Supervision, Resources, Writing - review & editing.Nicholas Shackel:Supervision,Writing - review & editing.Scott A Davison:Writing - review &editing.Emilia Prakoso:Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Sydney South West Area Health Service Ethics Committee.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Non-operative management of pancreatic trauma in adults

- Torin2 overcomes sorafenib resistance via suppressing mTORC2-AKT-BAD pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells

- Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of antiviral regimens for entecavir-resistant hepatitis B: A systematic review and network meta-analysis

- Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: An update on epidemiology, classification, diagnosis and management

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Safety and efficacy of an integrated endovascular treatment strategy for early hepatic artery occlusion after liver transplantation