Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of antiviral regimens for entecavir-resistant hepatitis B: A systematic review and network meta-analysis

2021-01-07SiSiYngChengWeiCiXueQingJiXuChengBoYu

Si-Si Yng , Cheng-Wei Ci , Xue-Qing M , Ji Xu , Cheng-Bo Yu , *

a State Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Infectious Diseases, Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310 0 03, China

b Department of Neurosurgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310 0 03, China

c Kidney Disease Center, the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310 0 03, China

Keywords:Chronic hepatitis B Drug resistance Entecavir Anitviral therapy

A B S T R A C T Background: Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients who had exposed to lamivudine (LAM) and telbivudine(LdT) had high risk of developing entecavir (ETV)-resistance after long-term treatment. We aimed to conduct a systematic review and a network meta-analysis on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness on antiviral regimens in CHB patients with ETV-resistance.Data sources: We searched PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science for studies on nucleos(t)ide analogues(NAs) treatment [including tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)-based rescue therapies, adefovir (ADV)-based rescue therapies and double-dose ETV therapy] in CHB patients with ETV-resistance. The network meta-analysis was conducted for 1-year complete virological response (CVR) and biological response (BR)rates using GeMTC and ADDIS. A cost-effective analysis was conducted to select an economic and effective treatment regimen based on the 1-year CVR rate.Results: A total of 6 studies were finally included in this analysis. The antiviral efficacy was estimated. On network meta-analysis, the 1-year CVR rate in ETV-TDF [odds ratio (OR) = 22.30; 95% confidence interval(CI): 2.78-241.93], LAM-TDF (OR = 70.67; 95% CI: 5.16-1307.45) and TDF (OR = 16.90; 95% CI: 2.28-186.30)groups were significantly higher than that in the ETV double-dose group; the 1-year CVR rate in the LAM-TDF group (OR = 14.82; 95% CI: 1.03-220.31) was significantly higher than that in the LAM/LdTADV group. The 1-year BR rate of ETV-TDF (OR = 28.68; 95% CI: 1.70-1505.08) and TDF (OR = 21.79;95% CI: 1.43-1070.09) therapies were significantly higher than that of ETV double-dose therapy. TDFbased therapies had the highest possibility to achieve the CVR and BR at 1 year, in which LAM-TDF combined therapy was the most effective regimen. The ratio of cost/effectiveness for 1-year treatment was 8 526, 17 649, 20 651 Yuan in the TDF group, TDF-ETV group, and ETV-ADV group, respectively.Conclusions: TDF-based combined therapies such as ETV-TDF and LAM-TDF therapies were the first-line treatment if financial condition is allowed.

Introduction

Hepatitis B is one of the most common infectious diseases in the world, highly epidemic in Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Pacific regions [1] . Untreated patients are at high risk of progressing to severe hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma(HCC) [ 2 , 3 ]. Since nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) are licensed for the treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB), NAs have been widely used for their potent efficacy and good tolerability.The primary proposal of NAs treatment is to suppress the replication of hepatitis B virus (HBV), reduce liver inflammation and prevent patients from disease progression [4-7] . Lamivudine (LAM),adefovir (ADV), entecavir (ETV), telbivudine (LdT), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) are prescribed to CHB patients at present.

LAM and ADV were the main antiviral medications before ETV and TDF were available. However, patients treated with LAM and ADV were at high risk of developing drug resistance after longterm treatment. Studies have shown that approximately 20% and 70% of CHB patients would develop drug resistance after 1-year and 5-year treatment of LAM, respectively [ 8 , 9 ], while 20% -29%patients would develop drug resistance after 5-year treatment of ADV [10] . When drug resistance developed, patients often experienced virological breakthrough, biochemical breakthrough, acute hepatitis B flare, and even progression to severe hepatitis.

As the first-line medications in most countries in the world,ETV, TDF and TAF have higher genetic resistant barriers and antiviral potency especially in treatment-naïve patients, with only 1.2% ETV-treated patients developing a resistant strain after 5-year therapy [ 5 , 11-15 ]. Unfortunately, owing to the existence of crossresistance between ETV and LAM, the proportion of LAM-refractory patients who developed ETV resistance reached approximately 50%after 5-year ETV therapy [ 11 , 16 , 17 ].

For the ETV-resistant CHB patients, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) in 2018 set a guideline [15] which recommended switching ETV to tenofovir(TDF or TAF) or emtricitabine-tenofovir combined therapy, or ETV add-on tenofovir (TDF or TAF) combined therapy; while European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) practice guideline [14] only recommended switching to TDF or TAF monotherapy. For those ETV-resistant CHB patients, there is no consensus on treatment regimens. In this study, we compared the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of all reported NAs treatment strategies for those ETV-resistant patients by performing a network meta-analysis and cost-effective analysis.

Methods

Search strategy

Two authors independently searched the PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science for studies concerning the effectiveness of rescue therapies in ETV-resistant patients of all kinds of races, published in English from 2013 to 2018 using keywords: hepatitis B,viral hepatitis, resistan*, entecavir resistan*, drug resistan*, drug therap*, rescue therapy, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine and tenofovir. In addition, reference lists from retrieved documents were reviewed, and a manual search was implemented to supplement the computer search. Authors downloaded and further screened the search results to a reference database.

Search details were as follows: ((((hepatitis b) OR viral hepatitis)) AND (((resistan*) OR entecavir resistan*) OR drug resistan*))AND (((((((drug therap*) OR rescue therap*) OR lamivudine) OR adefovir) OR entecavir) OR telbivudine) OR tenofovir).

The inclusion and exclusion criteria

We enrolled randomized control trails (RCT) and cohort studies. Patients were eligible if they developed genetic mutations after treatment of ETV with or without LAM-resistance. A treatment strategy was any NAs treatment with results in at least one study,whether recommended by current practice guidelines or not. We also set a restriction to the duration of follow-up, and at least a 48-week follow-up was required.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: studies on (1) pediatric group, pregnant group or liver transplantation group; (2) patients who received immunosuppressive therapy or who were treated with interferon and Chinese traditional medicine; (3) co-infection with hepatitis A, C, D, E virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); and (4) other acute or chronic liver diseases such as fatty liver, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis, and drug-induced liver injury.

Efficacy measurements and definition

The primary endpoint was complete virological response (CVR)and biochemical response (BR). Efficacy definitions were as follows: CVR was defined as undetectable HBV DNA level in serum;The lower limit for undetectable HBV DNA was determined as ≤20 IU/mL or 100 copies/mL by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays; and BR was defined as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level<40 IU/L.

Quality assessment and data extraction

The quality of each study was evaluated by the Cochrane tool and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale in RCTs and cohort studies, respectively. Two authors evaluated each publication and systematically reviewed the statistics. Any disagreement about publications and the extracted data was discussed and judged by a third author. The extracted statistics included: (1) study characteristics (author, publication date, area of origin, study design, sample size, and treatment strategies); (2) patients’ demographics [age, sex, level of baseline HBV DNA, status of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positivity, and status of liver cirrhosis]; (3) treatment details (dose of drug and duration of treatment); and (4) outcomes of the different treatment strategies (CVR and BR at 1 year or 48 weeks).

Statistical analysis

GeMTC v0.14.3 (IMI GetReal Initiative, EU) and ADDIS v1.16.18(IMI GetReal Initiative, EU) were used for network meta-analysis.The binary data were expressed as the odds ratio (OR) with a 95%confidence interval (95% CI). Traditional pair-wise meta-analysis was conducted using ADDIS v1.16.18 to compare two different antiviral regimens directly, calculatingI2to assess the heterogeneity for each paired comparison. The pooled estimates of ORs as well as 95% CI were reported in our results. Network meta-analysis was performed using GeMTC v0.14.3 based on Bayesian framework, and the parameters were set as number of chains: 4, tuning iterations:60 0 0 0, simulation iterations: 10 0 0 0 0, thinning interval: 10, inference samples: 20 0 0 0, and variance scaling factor: 2.5. Inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons was evaluated by the conduction of node-splitting analysis, and whenP<0.05 we assumed that there existed significant inconsistency. We used a consistency model to draw conclusions about the relative effect of the included treatment strategies when no relevant inconsistency was detected. Otherwise, an inconsistency model was used.An accumulated probability plot ofPvalue rankings showed the best therapeutic measures based on the Markov chain Monte Carlo method. STATA-14 (StataCorp, Texas, TX, USA) was used to draw network plots diagram. Each node represented a treatment regimen and the area of the node stood for the total sample size of the treatment. A line connected nodes when there was any study directly comparing the efficacy of the therapies and the width of the lines indicated the amount of studies.

Results

Search results and characteristics

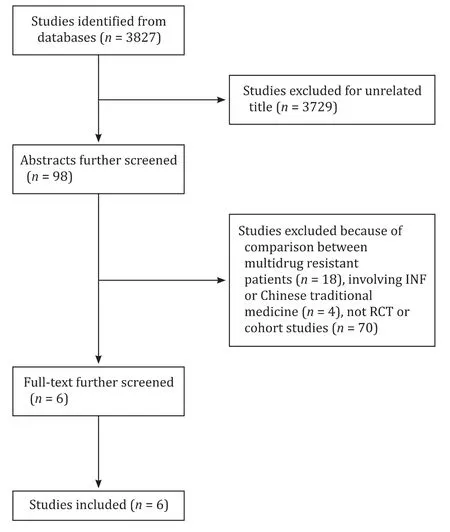

Fig. 1. The flowchart of the literature selection process.

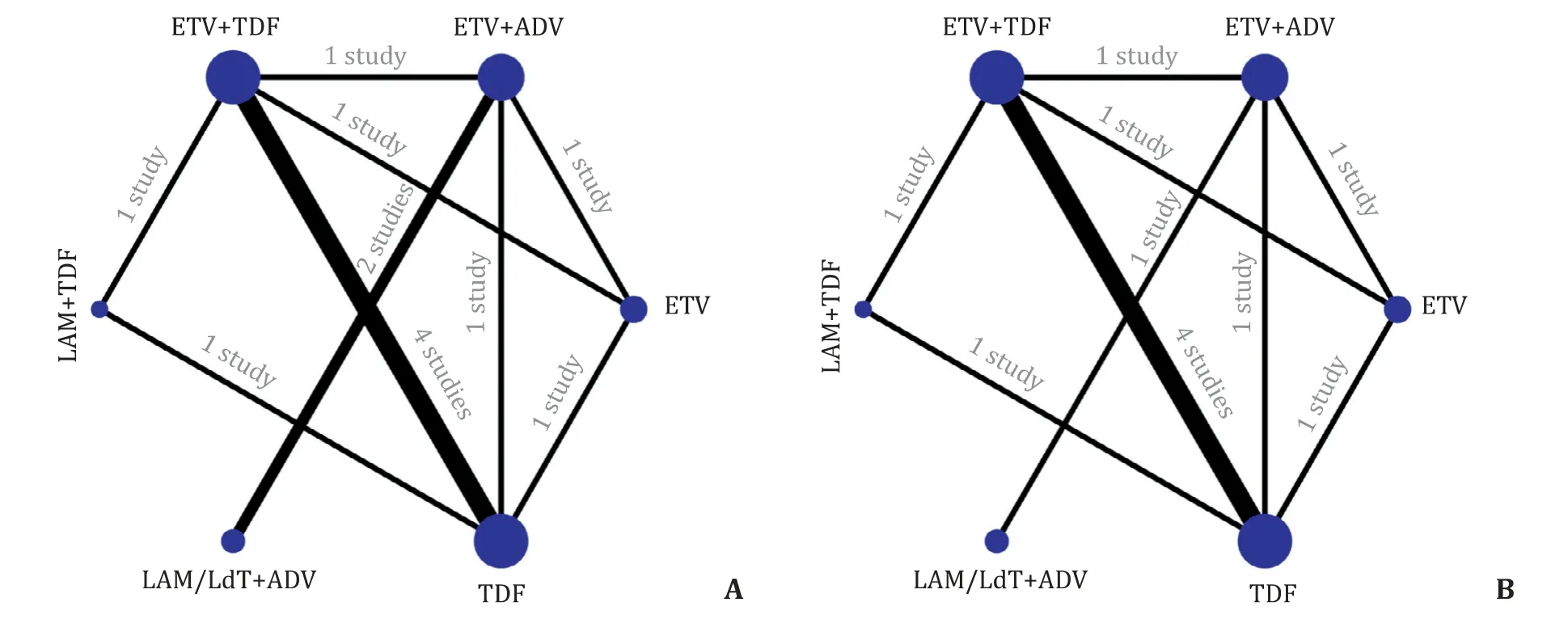

According to our searching strategies, 3827 articles were identified, and 3729 articles were excluded for their unrelated title. After further screening the abstract, 92 articles were excluded. Finally, 6 articles were enrolled, of which 1 was RCT and 5 were cohort studies. These 6 studies (13 treatment arms) involving a total of 477 patients fulfilled the criteria for this network meta-analysis ( Fig. 1 ).We divided these patients into 3 groups according to their therapeutic strategies, including TDF-based rescue therapies (including TDF mono-rescue therapy, LAM-TDF and ETV-TDF combined therapy), ADV-based combined therapies (ADV add-on ETV therapy and ADV add-on LAM/LdT combined therapy), and ETV double-dose(1 mg/day) therapy. Among these studies, 4 studies [ 13 , 18-20 ] involved TDF-based therapies, 3 [ 18 , 21 , 22 ] involved ADV-based therapies, and 1 [18] involved ETV double-dose treatment. The characteristics of the involved studies were summarized in Table 1 .Most of these patients were treated with TDF-based rescue therapies. The publication time of these enrolled studies ranged from 2013 to 2017. All subjects in 6 studies were Asian populations. Network evidence was shown in Fig. 2 . Four studies [ 13 , 18-20 ] directly compared the efficacy between TDF monotherapy and TDFETV combined therapy, while 2 studies [ 21 , 22 ] compared ETV-ADV and LAM/LdT-ADV combined therapy, and comparison between the rest of strategies reported in one study were collected from 3 studies [13 , 18 , 21] .

Pair-wise meta-analysis for 1-year CVR and BR rates

We directly compared the therapeutic effectiveness of these 6 antiviral regimens using DerSimonian-Laird random effect metaanalysis. All results were shown in Fig. 3 , suggesting no significant heterogeneity among groups. On the aspect of CVR at 1 year,the efficacy of ETV monotherapy was relatively poorer than that of ETV-ADV combined therapy (OR = 0.13; 95% CI: 0.02-0.78), TDF monotherapy (OR = 0.07; 95% CI: 0.01-0.43) and ETV-TDF combined therapy (OR = 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01-0.45). On the aspect of BR at 1 year, the efficacy of ETV monotherapy was relatively poorer than that of TDF monotherapy (OR = 0.07; 95% CI: 0.01-0.75) and ETV-TDF combined therapy (OR = 0.05; 95% CI: 0.01-0.66).

Network meta-analysis for 1-year CVR and BR rates

Node-splitting analysis suggested no significant difference between direct and indirect effects along with all potential scale reduction factors (PSRFs) valued from 1.00 to 1.01. Therefore, the consistency model was applied for network analysis . The results were shown in Fig. 4 . ETV-TDF (OR = 22.30; 95% CI: 2.78-241.93),LAM-TDF (OR = 70.67; 95% CI: 5.16-1307.45) and TDF (OR = 16.90;95% CI: 2.28-186.30) groups had significantly higher 1-year CVR rates than ETV double-dose group; LAM-TDF (OR = 14.82; 95%CI: 1.03-220.31) had a higher 1-year CVR rate than LAM/LdT-ADV.ETV-TDF (OR = 28.68; 95% CI: 1.70-1505.08) and TDF (OR = 21.79;95% CI: 1.43-1070.09) therapies had significantly higher 1-year BR rates than ETV double-dose therapy. There were no significant differences between the rest of paired comparisons in treatment effectiveness.

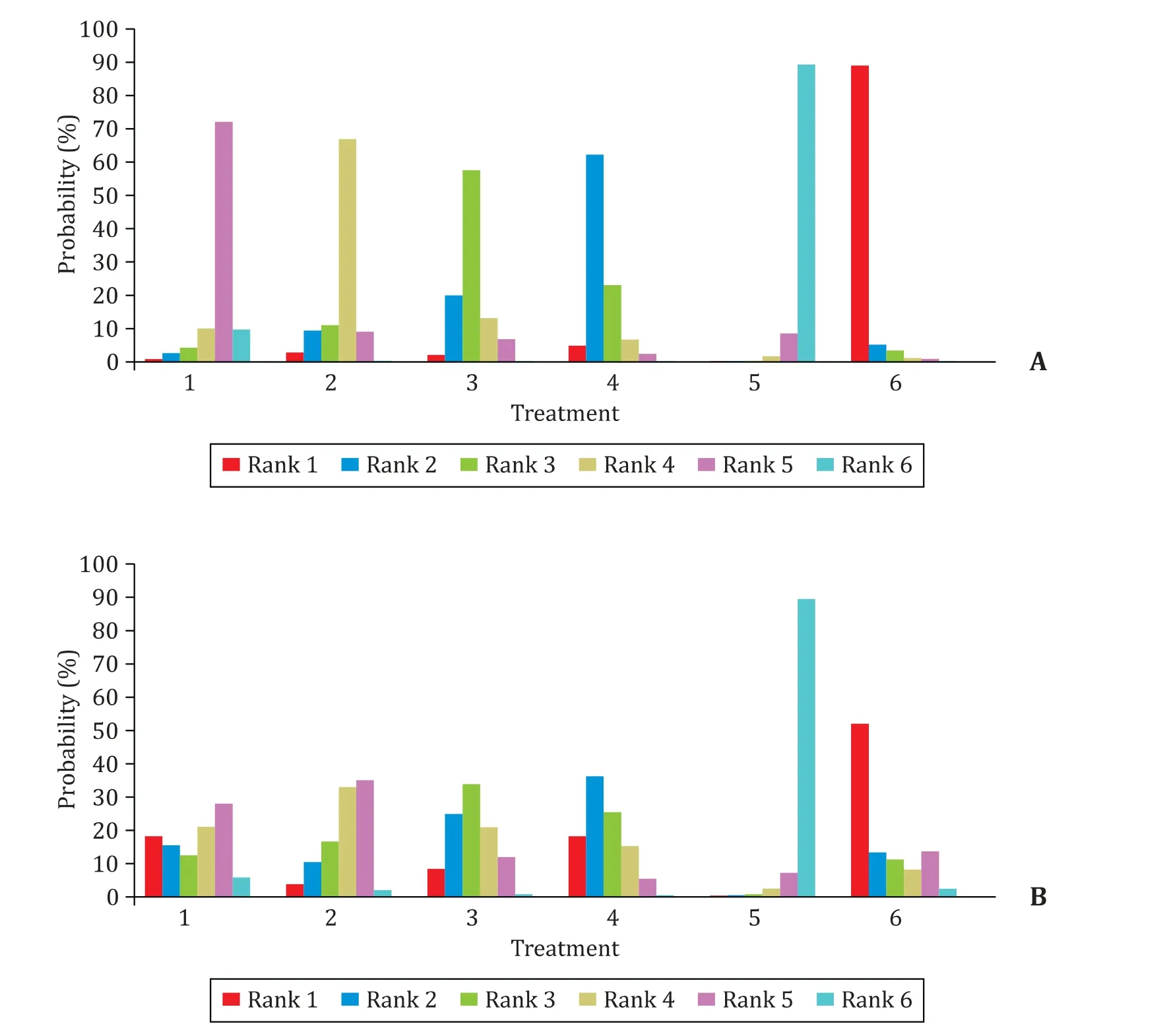

Rank probability

Fig. 5 shows the possibility of the therapeutic effects on ETVresistant CHB patients for the 6 antiviral regimens. The results suggested that the possibility of achieving CVR at 1 year ranked as LAM-TDF, ETV-TDF, TDF, ETV-ADV, LAM/LdT-ADV and ETV in order of effectiveness; while BR at 1 year ranked as LAM-TDF, ETV-TDF,TDF, LAM/LdT-ADV, ETV-ADV and ETV. LAM-TDF therapy had the highest possibility to achieve 1-year CVR and BR rates (90% and 52%, respectively), while ETV monotherapy had the lowest possibility to achieve 1-year CVR and BR rates (11% and 12%, respectively).

Factors predicting the virological response

In 5 [ 13 , 19-22 ] of 6 studies (another study did not mention the predict factors), multivariate analysis showed that baseline HBV DNA level was an independent factor of achieving CVR at 1 year, and that patients with lower HBV DNA level had the tendency to achieve CVR. Exposure to ADV before TDF-based therapies was negatively associated with CVR [19] . In addition, one study [22] suggested that early virological response (within 3 months) was independently associated with higher CVR. In 2 studies [ 20 , 21 ], positive HBeAg was associated with higher CVR in univariate analysis, but was not an independent factor.

Safety

There were no severe adverse events that resulted in alternation to other treatment regimen or drug discontinuation. No patients experienced increase in serum creatinine levels of ≥0.5 mg/dL above baseline. In addition, the occurrence of virological breakthrough was not significantly different among groups, mostly owing to the bad adherence to NAs.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The total cost included examination fees, hospitalization expenses, and medicine costs. Since patients’ examination fees and hospitalization costs were comparable, we calculated the cost of the drug based on the retail price of medication in the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine in 2018.The ratio of cost/effectiveness for 1-year treatment was 8 526,17 649, and 20 651 Yuan (USD 1203, 2491 and 2915) in the TDF group, TDF-ETV group, and ETV-ADV group, respectively. The cost/effectiveness was the highest in TDF monotherapy. Although TDF-ETV combined rescue therapy was more effective in achieving CVR at 1 year than TDF monotherapy, the incremental costeffectiveness ratio (ICER) was 397 296 Yuan/%. The price of medication changes with the policy of medical insurance. It is calculated that when ETV’s price falls to 2.2% of the price of TDF, TDF-ETV combined therapy will undoubtedly become the most economic and effective treatment option.

Fig. 2. Network plots of available treatment comparisons for 1-year CVR ( A ) and BR ( B ). LAM: lamivudine; ADV: adefovir; ETV: entecavir; TDF: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate;LdT: telbivudine.

Fig. 3. Pair-wise meta-analysis for 1-year CVR and BR. CVR: complete virological response; BR: biochemical response; CI: confidence interval; LAM: lamivudine; ADV: adefovir; ETV: entecavir; TDF: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; LdT: telbivudine. The former group was assigned to the control group.

Assuming that the cost of each group is reduced by 10%, the results of the three treatment options are not affected by sensitivity analysis ( Table 2 ).

Discussion

This meta-analysis compared the antiviral efficacy of different treatment strategies applied for ETV-resistant CHB patients and classified these patients into three treatment groups, including TDF-based therapies, ADV-based therapies and ETV double-dose therapy. An effective rescue therapy for ETV-resistant patients relies on knowledge of cross-resistance among NAs. Unfortunately,resistance to ETV conveyed cross-resistance to LdT and LAM, which had lower antiviral efficacy and lower genetic barrier than ETV.TDF and ADV had no cross-resistance and showed active antiviral efficacy in ETV-resistant CHBinvitrostudies [ 23 , 24 ].

Fig. 4. Network meta-analysis of the therapeutic efficacy of different treatment regimens. The values stood for the OR of the column treatment strategy compared to row treatment strategy. A: CVR; B: BR. CVR: complete virological response; BR: biochemical response; OR: odds ratio; LAM: lamivudine; ADV: adefovir; ETV: entecavir; TDF:tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; LdT: telbivudine.

Fig. 5. Possibility of the efficacy in different treatment strategies for 1-year CVR ( A ) and BR ( B ). 1: LAM-ADV combined therapy; 2: ETV-ADV combined therapy; 3: TDF monotherapy; 4: ETV-TDF combined therapy; 5: ETV double-dose therapy; 6: LAM-TDF combined therapy.

Table 2 Cost-effectiveness analysis of three treatment regimens.

TDF is one of the most potent NAs with the highest genetic barrier to resistance. It has been proven to be effective in treatment-naïve, drug-refractory and even drug-resistant patients, and was recommended by many guidelines [ 14 , 15 , 19 , 25-29 ]. Treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B patients have not been reported to develop resistant mutations during long-term antiviral therapy of TDF [ 30-32 ]. However,the primary shortcomings we often paid attention to were its adverse events, such as bone and renal toxicity [ 33-35 ]. However,TDF-based rescue therapies in this network meta-analysis were well-tolerated with the highest possibility in achieving CVR and BR comparing with ETV and ADV-based rescue therapies, among which LAM-TDF combined therapy ranked the most effective one. Only a few patients experienced virological breakthrough,mostly resulting from their bad compliance to medications. No additional HBV resistance mutations were observed in neither TDF monotherapy, LAM-TDF nor TDF-ETV combination therapy patients.

ADV is another NAs used to be widely prescribed to CHB patients, which shows efficacy similar to TDFinvitrostudies [ 23, 24].The combined treatment of ADV and LAM has been confirmed to exhibit great potency in LAM-resistant patients, for ADV has additive efficacy in inhibiting HBV when combining with pyrimidine analogues such as LAM, LdT and ETV [36-41] . In addition, combined therapy could help reduce the occurrence of mutations. In this study, ADV-based therapies exhibited potent effectiveness in suppressing the replication of HBV and normalizing ALT, although the efficacy was lower than TDF-based therapies.

Some studies have shown that the blood concentration of ETV might positively influence the efficacy of the treatment, and in patients with high blood concentration it even reverses liver fibrosis [ 42-44 ]. ETV has less adverse events than TDF or ADV, such as hypophosphatemia, bone and renal toxicity [ 33-35 ]. The network analysis showed that ETV was a suboptimal regimen for ETVresistant patients because the efficacy in achieving CVR and BR was lower than TDF-based or ADV-based therapies.

As far as we know, this is the first meta-analysis to systematically compare the treatment strategies in ETV-resistant CHB patients. There are two limitations. First, the studies included were all from Asia. As it is well known that high-barrier antiviral drugs were approved late in this area which prolonged LAM and ADV applications as the first-line. Second, not all the studies enrolled had direct therapeutic comparisons.

In conclusion, TDF-based rescue therapies should be the optimal option for ETV-resistant patients. ADV-based therapy might be recommended if there is no access to TDF. Continuing ETV treatment is not recommended for ETV-resistant patients. TDF-based combined therapy has higher possibility to achieve 1-year CVR and BR, but TDF monotherapy could be firstly recommended for patients who have financial difficulties according to cost-effective analysis. In addition, TDF-ETV combined therapy will be the best fit for ETV-resistant patients if the price of ETV drops to 2.2% of the price of TDF.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Si-Si Yang:Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing - original draft.Cheng-Wei Cai:Project administration,Methodology, Resources.Xue-Qing Ma:Data curation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing.Jia Xu:Writing - original draft,Software.Cheng-Bo Yu:Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing- review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Scientific and Technological Major Project of China (No. 2017ZX10105001).

Ethical approval

Not needed.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Non-operative management of pancreatic trauma in adults

- Torin2 overcomes sorafenib resistance via suppressing mTORC2-AKT-BAD pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells

- Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: An update on epidemiology, classification, diagnosis and management

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Safety and efficacy of an integrated endovascular treatment strategy for early hepatic artery occlusion after liver transplantation

- Virtual navigation-guided radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma invisible on ultrasound after hepatic resection