Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: An update on epidemiology, classification, diagnosis and management

2021-01-07DimitriosShizsAikteriniMstorkiEleniRoutsiMihilPppnouDimitriosTsprlisPntelisVssiliuKonstntinosToutouzsEvngelosFelekours

Dimitrios Shizs , Aikterini Mstorki ,, Eleni Routsi , Mihil Pppnou ,Dimitrios Tsprlis , Pntelis Vssiliu , Konstntinos Toutouzs , Evngelos Felekours

a First Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laikon General Hospital, Athens, Greece

b Fourth Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Attikon University Hospital, Athens, Greece

c Surgical Department, General Hospital of Ierapetra, Ierapetra, Greece

d First Department of Propaedeutic Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Hippocration Hospital, Athens, Greece

Keywords:Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma Classification Diagnostic approach Therapeutic management

A B S T R A C T Background: Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (CHC) is a rare subtype of primary hepatic malignancies, with variably reported incidence between 0.4%-14.2% of primary liver cancer cases. This study aimed to systematically review the epidemiological, clinicopathological, diagnostic and therapeutic data for this rare entity.Data sources: We reviewed the literature of diagnostic approach of CHC with special reference to its clinical, molecular and histopathological characteristics. Additional analysis of the recent literature in order to evaluate the results of surgical and systemic treatment of this entity has been accomplished.Results: The median age at CHC’s diagnosis appears to be between 50 and 75 years. Evaluation of tumor markers [alpha fetoprotein (AFP), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)] along with imaging patterns provides better opportunities for CHC’s preoperative diagnosis.Reported clinicopathologic prognostic parameters possibly correlated with increased tumor recurrence and grimmer survival odds include advanced age, tumor size, nodal and distal metastases, vascular and regional organ invasion, multifocality, decreased capsule formation, stem-cell features verification and increased GGT as well as CA19-9 and CEA levels. In case of inoperable or recurrent disease, combinations of cholangiocarcinoma-directed systemic agents display superior results over sorafenib. Liver-directed methods, such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), radioembolization and ablative therapies, demonstrate inferior efficacy than in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) due to CHC’s common hypovascularity.Conclusions: CHC demonstrates an overlapping clinical and biological pattern between its malignant ingredients. Natural history of the disease seems to be determined by the predominant tumor element.Gold standard for diagnosis is histology of surgical specimens. Regarding therapeutic interventions, major hepatectomy is acknowledged as the cornerstone of treatment whereas minor hepatectomy and liver transplantation may be applied in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Despite all therapeutic attempts,prognosis of CHC remains dismal.

Introduction

Primary hepatic neoplasms (PHNs) consist of a heterogeneous group of epithelial, mesenchymal and mixed tumors. Epithelial malignancies, also known as hepatic carcinomas, occupy the 6th overall place in international cancer frequency and include hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cholangiocarcinoma (CC) and combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (CHC). HCC is the most common primary liver malignancy and originates from hepatocytes,whereas CC is the second most frequent and derives from epithelial cells of the intrahepatic bile duct [1 -6] . CHC is only a rare subtype of primary hepatic malignancies [7 -9] . CHC is at present recognized as a distinct entity, intimately combining clinicopathological and radiological features from both HCC and CC in the same tumor, thus demonstrating its ambiguous character [10 -14] . As far as its cellular origin is concerned, there is still no definite evidence but one hypothesis tends to predominate; CHC seems to derive from the bipotent hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs) with both hepatocellular and cholangiocellular differentiation potential. Redifferentiation or dedifferentiation of the hepatocellular to biliary phenotype orviceversais the alternative but still controversial theory [2 , 15 , 16] .

Gold standard for diagnosis is histology of operative specimens after resection [16 -18] . Preoperative diagnosis is a challenge for the clinician and requires the interpretation of imaging patterns emerging in ultrasound (US), contrast enhanced computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and laboratory findings, especially tumor markers [alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and carcinoembryonic antigen(CEA)] [1 , 14 , 19] . Regarding possible therapeutic interventions, major hepatectomy is acknowledged as the cornerstone of CHC treatment whereas minor hepatectomy and liver transplantation are applied in patients with advanced cirrhosis who should avoid the devastating effects of an aggressive excision [3 , 7 , 8 , 16 , 20 -22] . Despite all therapeutic attempts, prognosis remains poor with lower overall survival (OS) rates than HCC but higher than CC, thus indicating intermediate biological behavior [15 , 16 , 23 -27] . The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature on CHC and report epidemiological, clinicopathological, diagnostic and therapeutic data for this rare entity.

Epidemiology and classification

Reported prevalence of CHC has varied, ranging from 0.4% -14.2% of PHNs, with growing incidence and mortality in recent years [7 -9 , 28] . Spolverato et al. reported an almost doubled number of diagnosed CHC cases between 2004 and 2015,attributed to its accurate recognition as a distinct entity and a true increase in incidence [23] . In a study of 20 0 0 0 patients with primary liver cancer, conducted from SEER database, CHC presented an overall incidence of 1.3% of total cases [29] . In another large population-based retrospective study of 529 patients, CHC demonstrated a mean age at diagnosis of 62.5 years and an overall incidence of 0.05 per 10 0 0 0 0 per year. Incidence was actually found to be correlated with male sex and age. The median age at CHC’s diagnosis appears to be between 50 and 75 years. Maximum incidence was observed between 60-64 years for men and 75-79 years for women [30] . Western studies generally suggest an older mean age of onset and no male predominance [1 , 7 , 19] , in contradiction to Eastern studies, which present an earlier appearance as well as a correlation of the disease with male sex [20 , 23] .

Histological classification of CHC has been thoroughly studied and described with many different systems throughout its historical evolution. First attempts were made by Allen and Lisa in 1949 and Goodman in 1985 with systems consisting of 3 subtypes[16] . The contemporary version is based on well established World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. With the 2010 WHO classification, CHC was first recognized as a distinct entity and was divided into two different subtypes: the classical and most common subtype, which is mixture of typical HCC and CC components with transition zones; and a second type with stem-cell features, consisting of three different variants, 1) typical, with mature hepatocytes surrounded by HPC-like cells; 2) intermediate, with simultaneous expression of both hepatocellular and cholangiocellular immunohistochemical markers; 3) and cholangiolocellular (CLC), consisting of cells immunohistochemically recognized as HPCs, but morphologically organized in tubular cholangioles within a desmoplastic stroma [15 , 18 , 31] . Based on molecular findings, the latest 2019 WHO classification simplified categorization as it eliminated CLC from CHC subtypes. CLC, which was the less understood variant, is now considered a subtype of small duct intrahepatic CC and is renamed as cholangiolocarcinoma. As a matter of fact, intrahepatic carcinomas with ductal and tubular phenotype are now included within the category of intrahepatic CC [32] .

Molecular findings

Molecular biology of CHC has not yet been completely clarified. The genetic landscape of CHC demonstrates a diverse range of mutations, which overlap with those seen in HCC and CC. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at 3p and 14q chromosomes, inactivation ofTP53, activation of TGF-β, mutations ofKRAS,TERTpromoter, Wnt-pathway (CTNNB1/β-catenin) and cell-cycle genes as well as alterations in chromatin regulators (ARID1AandARID2)have been involved in its evolution [22 , 33 -36] . Whether CHC genetically resembles more HCC or CC remains a controversial issue.Cazals-Hatem et al. observed the existence ofLOHandTP53mutations in more than 50% of CHC and CC cases and stated that the genetic patterns displayed by the combined tumors are chiefly CC-orientated [35] . On the contrary, after comparing CHCs with cirrhotic intrahepatic CCs, Joseph et al. concluded that CHC’s molecular profile presented hepatocellular features even in the CC component [36] . No typical CC alterations (IDH1/2,FGFR2,andBAP1) were identified. It was also suggested thatTERTpromoter mutations might be an early event in CHC evolution since they were consistently observed in both HCC and CC components [36] . Another study divided CHC into two molecular subclasses: the classical subclass that consists of two components with common clonal origin and the more aggressive stem-cell subclass with progenitor-like genetic traits. The same study demonstrated that CLC exhibits a biliary molecular profile [37] .

The latter was supported by the more recent results of Balitzer et al. [38] . Capture-based next generation sequencing revealed that typical CC mutations (IDH1/2,PBRM1, andFGFR2fusions) were present in more than 90% of the CLC components analyzed. It was therefore recommended that CLC should be considered neither as a distinct entity nor as a CHC subtype unless it is accompanied by a distinct hepatocellular component. It should actually be categorized as a subtype of intrahepatic CC [38] .

Risk factors and clinical features

The risk factors for both HCC and CC are also risk factors for CHC. Viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, alcohol consumption and male sex are some of the most widely reported factors presumably involved in the etiology of CHC development, whereas family history of liver cancer in CHC patients is sporadically observed in some systemic studies. This effect is still not completely confirmed [2 , 16] . Diabetes mellitus and obesity are presented more as possible confounding rather than true risk factors for the appearance of CHC,as they account for the evolution of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and subsequent cirrhosis [2 , 20] . Three reported cases in USA and Philippines are noteworthy as they support a potential relationship between liver fluke infections (Schistosoma mansoni and Clonorchis sinensis) and CHC development [28 , 39] . This is the only possible CC-related etiopathogenic factor of CHC. However the validity of this connection requires further investigation. Geographical heterogeneity of risk factors described is in total association with different lifestyle and prevalence of infections between Eastern and Western regions. The vast majority of Eastern studies,in resemblance to HCC, reported chronic viral hepatitis, especially HBV infection and cirrhosis as a fundamental predisposing factor involved in pathogenesis of CHC [15 , 21 , 24 , 40 , 41] . In contrast, Western studies correlated CHC neither with chronic liver disease nor with cirrhosis, considering it as more akin to CC [42 , 43] . Accurate determination of risk factors remains elusive, considering that the conducted studies are based on small samples with possible selection bias.

CHC demonstrates an overlapping clinical and biological pattern between its malignant ingredients [16 , 44] . It generally manifests silent expansion in early phase with symptoms and signs such as painless jaundice, pruritus, abdominal discomfort, weight loss, fever, fatigue, ascites, hepatomegaly, palpable gallbladder and acute cholangitis [45] . Natural history of the disease seems to be determined by the predominant tumor element [15] . HCC-related behavior of the tumor is indicated by direct, especially bile duct,invasion, microsatellite and capsule formation as well as microvascular and macrovascular invasion (portal vein thrombus), leading to portal or hepatic vein permeation [1 , 7 , 8 , 15 , 24 , 44] . Despite its assumed hepatocellular nature, capsular formation is less frequently observed in CHC than pure HCC in concordance with the more invasive aspect of the combined tumor [1 , 22 , 24] . Additionally, CHC’s tendency to emerge as multiple hepatic lesions is possibly associated with hepatocellular behavior; however the likelihood of that occurring is significantly higher than in CC or HCC [1 , 17] .CC-related behavior is conversely implied by multiregional lymph node metastases and tumor hypovascularity [1 , 7 , 8 , 15 , 24] . Hilar node metastases are in fact commonly observed, with reported frequency ranging from 12% to 33%, while incidence of extrahepatic metastases varies, with lungs, bones, brain and adrenal glands constituting the reported sites [17 , 46 -48] .

Histopathology

Detailed knowledge of CHC’s various morphological and immunohistochemical aspects is of vital significance and a true challenge for the pathologist. CHC most commonly appears as the classical type, which is characterized by variably differentiated adjoining (not in separate foci) HCC and CC areas along with an interface of intimate intermingling of the two unequivocal components [16 , 18] . The hepatocellular component may be recognized by the appearance of bile-producing cells (and canaliculi) with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, probably containing one or more of intracytoplasmic fibrinogen, Mallory-Denk bodies,α1-antitrypsin and fat globules [16, 18, 49, 50]. Tumor cells are arranged in a trabecular or pseudoglandular pattern within a scant stroma [16 , 18 , 22 , 49] . Common immunohistochemical markers include HepPar1, glypican-3 (highly sensitive and specific to HCC component), CAM5.2, canalicular pCEA and CD10, AFP as well as CK8 and CK18 [7 , 14 , 16 , 18 , 49 , 51 , 52] . In contrast, the biliary constituent is composed of low cuboidal/columnar mucin-producing cells, arranged in true glandular structures within a dense desmoplastic stroma [16 , 22 , 23 , 49] . Typical stains and immunohistochemical markers contain mucin/mucicarmine, pCEA (cytoplasmic and/or membranous), cytoplasmic CD10, AE1, MOC31 as well as CK7 and CK19 [16 , 18 , 49] . Transition zones often stain positively with CK7/CK19 and HepPar1. Albumin mRNA, detected byinsituhybridization, has also been used as hepatocellular marker in transition areas [18 , 26 , 51] .

The second great histopathological group of CHC cases is designated by the predominance of cells with stem/progenitor cell phenotype including hyperchromatic nuclei and high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio [50 , 51] . In the typical variant, these cells surround central islets of mature hepatocytes, forming lineage-like progressions from an immature periphery to a better differentiated center. Mitotic activity is rarely observed. Markers expressed by the peripheral clusters of progenitor-like cells include CK7,CK19, CD56, EpCAM, c-KIT/CD117, CK10 and DLK1 [16 , 18 , 50 , 51] .Intermediate-cell variant typically consists of a monomorphic tumor with cuboidal/oval shaped cells, smaller than hepatocytes but larger than progenitor-like cells, forming trabeculae, cords, solid nests or ill-defined gland-like structures within a fibrotic or acellular and hyalinized stroma. The development of intravascular, intrabiliary, lymphatic or perineural spread patterns often emerge in this variant. Cellular atypia and mucin production are uncommon.The tumor cells often show expression of c-KIT, as well as coexpression of both HepPar1 and CK19 or CEA [16 , 50 , 51 , 53] . However, Akiba et al. exhibited that CHCs stain better with arginase-1 and CK8 [54] . Malic enzyme 1 is also a lately proposed diagnostic marker of the intermediate-cell subtype [55] . Sasaki et al. reported that the intermediate subtype is associated with more frequent appearance in female sex, larger tumor size, higher histological grade of the HCC element and a scant fibrotic background [31] .

Diagnostic modalities

Laboratory findings

Tumor markers, including AFP, CA19-9 and CEA, should always be evaluated. Reported AFP levels of CHC tend to be lower than those in HCC but significantly higher than those in CC cases [15 , 56] . Lee et al. showed that AFP reached levels higher than 400 ng/mL in 21.2% of CHC cases; a limit which was never surpassed by CC patients [1] . As expected, reported CA19-9 levels of CHC exhibited conversely lower than CCs but substantially higher than pure HCCs [1 , 15] . Moreover, Wakizaka et al. proceeded to parallel estimation of CEA, detecting it elevated in 25% of affected patients and advocated measurement of PIVKA-II as an additional biomarker for assessment of the hepatocellular component. Resembling AFP, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II(PIVKA-II) levels noted in CHC patients were analogous to HCC but significantly higher than CC cases [17] . Among the aforementioned tumor markers, AFP and CA19-9 seem to be of higher diagnostic value because their concomitant increase should be considered a powerful indication of CHC diagnosis [1 , 15 , 16 , 57] .

Imaging studies

Diagnosis of such a complicated entity cannot be based exclusively on laboratory findings. Imaging provides crucial information about morphology and composition of the tumor, being highly suggestive of CHC in case of overlapping features between HCC and CC [16 , 18] . In USA, CHC typically emerges as a hypoechoic mass with central hyperechoic focus or as a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass mimicking HCC. US may also be used for obtaining imageguided targeted samples from suspicious lesions [22] . Utility of contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) in disease detection has also been studied. Enhancement patterns of multiphasic CEUS are divided into two main categories: HCC-like, when heterogeneous and secondarily homogeneous hyperenhancement are accompanied by a slow wash-out in portal or late phase; and CC-like in case of peripheral rim-like hyperenhancement followed by quick and marked washout [57 , 58] . CEUS was suggested as a preferable method for initially identifying malignant nature of hepatic lesions rather than differentiating CHC from pure HCC [58] . In a retrospective imaging analysis of 37 pathologically confirmed CHCs, CEUS had the highest risk of misdiagnosing CHC for pure HCC, when compared either with contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) or MRI, with sensitivity of the method decreasing with mass size [59] .

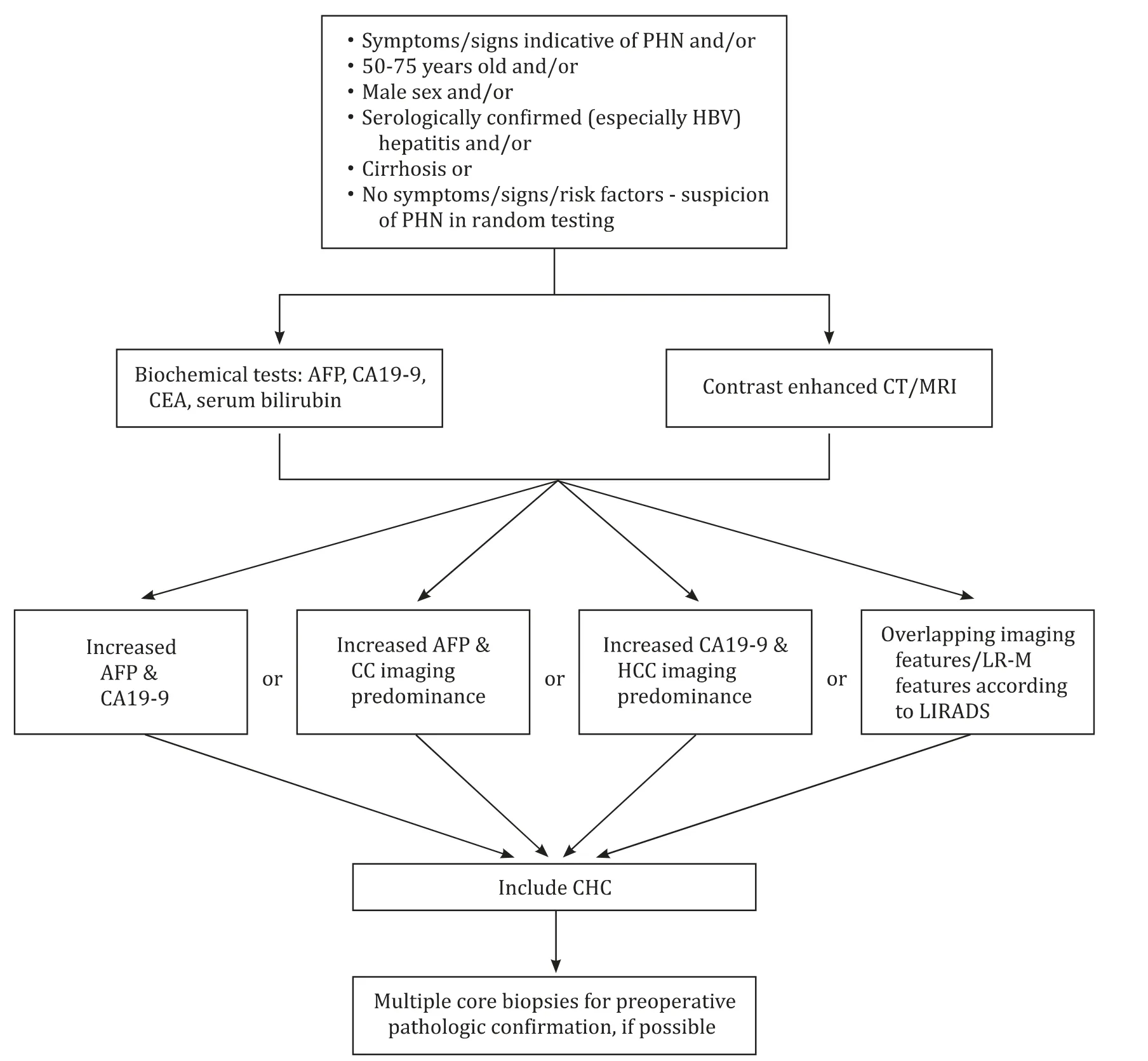

In multiphasic CT/MRI these lesions may display two different patterns in various proportions: a predominant HCC-like pattern,which is typified by arterial hyperenhancement followed by portal wash-out and an enhancing pseudocapsule on delayed imaging;or a prominent CC-like pattern typically illustrated by rim arterial enhancement with progressive centripetal enhancement of fibrous stroma, capsular retraction and biliary duct dilatation. Apparently, a mixture of both patterns may also be strongly indicative of CHC [22 , 56 , 60] . Gigante et al. showed that combining this mixed pattern with tumor biopsy is a strategy which improves CHC’s diagnostic performance [61] . It is suggested that larger masses tend to mimic CC enhancement due to ischemia and tissue necrosis leading to hypovascularity [62] . The dynamic enhancement patterns of CHC currently correspond better to Aoki’s type A and Sanada’s type III [22 , 62] . According to Sagrini et al., CECT exhibited superior outcomes to both MRI and CEUS in distinguishing CHC from HCC, with higher sensitivity for smaller lesions [59] .Many studies have highlighted that the evaluation of tumor markers along with imaging signs seems to offer better opportunities for accurate preoperative diagnosis of CHC than laboratory or radiological findings individually [16-18] . In particular, Li et al. indicated that synchronous elevation of AFP and CA19-9 was observed only in 15.6% of patients, whereas tumor marker elevation in discordance with imaging appearance on CEUS and CECT was demonstrated in 51.1% and 53.5% of patients, respectively [57] .

Radiological distinction between the atypical HCCs and the morphologically almost identical, yet more aggressive, CHC might be supported by LR-M features of the Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LIRADS). LR-M criteria facilitate a robust analysis of lesions with high probability or certainty of malignancy but not HCC specific appearance [63] . According to Sagrini et al., their predictive precision for CHC was maximum (52.9%) when CT-scan was the selected imaging method, minimum for CEUS (25.9%), while MRI attained intermediate results (35.3%) [59] . CT/MRI LR-M criteria are divided into two subgroups. The first subgroup is comprised of masses designated as targetoid when displaying at least one of targetoid dynamic appearance, delayed central enhancement,targetoid diffusion restriction or signal intensity on transitional or hepatobiliary phase. The second one consists of non-targetoid masses demonstrating other ancillary LR-M features [63-65] .According to Lee et al., presence of 3 or more LR-M features yielded the highest diagnostic accuracy for CHC, while targetoid appearance attained maximum sensitivity [64] . Despite their assistance, LR-M criteria should not be utilized as a sole diagnostic pathway [63 , 64] . Other imaging methods include applications of MRI such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) as well as positron emission tomography (PET), when possibility of recurrence is investigated ( Fig. 1 ) [45 , 60] .

Cytology-histopathology

If highly suspicious of the combined tumor, the clinician should order multiple image-guided core biopsies from various tumor areas. Dependence of a preoperative biopsy’s diagnostic accuracy on the area sampled, can be explained by the fact that presence of a transitional zone within the specimen is required to diagnose the most common classical CHC [16 , 22 , 50] . It is that histological heterogeneity, which makes definite diagnosis on cytological material alone almost impossible. Consequently, histopathological examination of surgical specimens after excision remains the gold standard method for diagnosis, as all tumor sites are obtainable for analysis.

Management

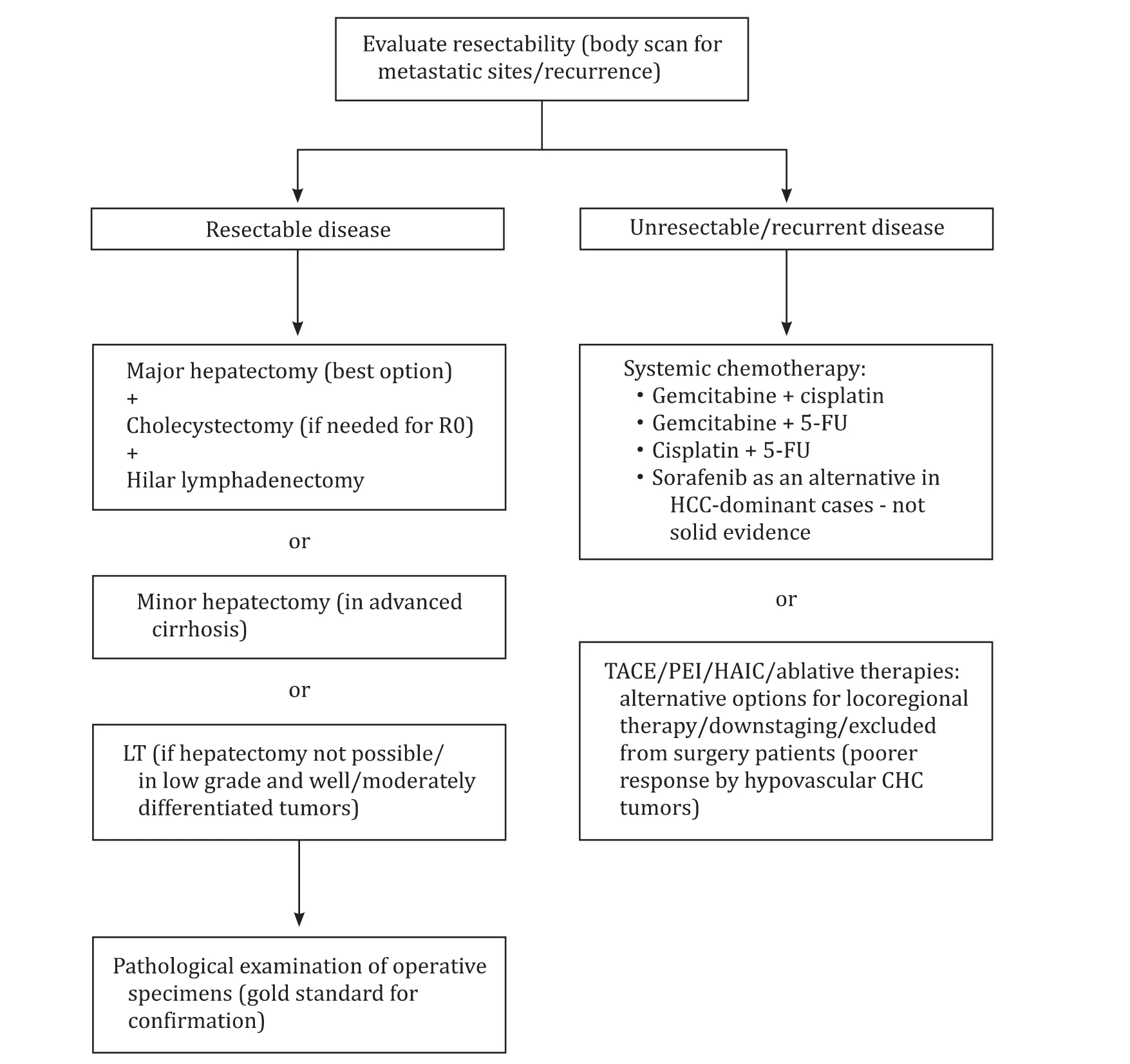

Despite progress in therapeutic interventions, CHC is still considered an aggressive tumor with unfavorable prognosis and minimal improvement of survival rates [16] . Therapeutic strategy depends on potential disease resectability. Specifically, surgical resection remains the cornerstone of treatment and the only wellacquainted curative option, yielding better survival benefits for the patient [3 , 7] . The extent of excision is basically determined by tw o parameters: the absolute necessity for achieving R0 resection and minimal damage on liver function, reserving as much functional liver parenchyma as possible. Major hepatectomy is considered the best option for accomplishing R0 resection [18] . Considering the coexistence of two components within the same tumor, with HCC infiltrating portal and hepatic veins and CC expanding through lymph nodes, hilar node dissection is recommended along with hepatic resection in either minor or major hepatectomy, although its benefit in survival rates remains a matter of controversy [8 , 66] .Besides, lymph node status as a determinative factor for postoperative prognosis reinforces necessity for nodal dissection [23] . Due to their limited hepatic functional reserve, cirrhotic patients should avoid the detrimental effects of extended surgery and should preferably undergo minor hepatectomy. Child-Pugh and model for end stage liver disease (MELD) scores could be utilized for functional assessment and prediction of postoperative mortality [45] .According to Tao et al., aggressive surgical treatment should be considered a potential solution for elderly patients as well, offering survival rates comparable to younger patients [3] .

In highly cirrhotic patients (Child-Pugh B or C), liver transplantation (LT) may be an alternative but less effective choice due to relapse caused by the biliary cellular content. The latter may be the reason for which LT for CHC seems to provide a survival benefit similar to LT for CC, yet inferior to LT for HCC. Since there is considerable debate over the results of LT for CC, with its indications being primarily restricted to early unresectable CCs after neoadjuvant chemoradiation, the value of this option for CHC remains questionable [67 , 68] . Nonetheless, Lunsford et al. stated that only patients with low grade and well or moderately differentiated tumors seem to actually benefit from LT, with a low-risk post-LT recurrence potential. This enforces the necessity for pretransplant tumor identification in order to accurately recognize this subset of patients [69] . Therefore, although LT has demonstrated survival benefit for patients with HCC, there is limited data to support or refute transplantation for CHC. Nevertheless, it has been elucidated that transplantation for localized CHC confers a survival benefit similar to liver resection, but inferior to transplantation for HCC affected patients. In conclusion, recent surveys’ results demonstrated that patients undergoing LT for HCC present better overall survival in comparison with those with CHC. Furthermore, attempts should be made to identify CHC patients prior to transplantation and to better understand predictors of outcomes, which could help to standardize selection criteria.

In case of inoperable or recurrent CHC, non-surgical treatment modalities including systemic chemotherapy and liver-directed procedures are ordinarily accomplished for amelioration of symptoms. Non-surgical options encompass methods such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), percutaneous ethanol injection(PEI), hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), radioembolization and ablative therapies with limited number of studies on their application in CHC patients [18 , 21] . TACE, which is predominantly used as a palliative treatment for recurrent HCC, may also prolong the survival of some patients with recurrent or unresectable CHC, though it still demonstrates inferior effectiveness than in HCC cases due to the commonly presented tumor hypovascularity. The validity of this hypothesis is reinforced by the results of a retrospective analysis of 42 recurrent CHC cases, in which TACE was applied. This study compared not only response to TACE between CHC patients and HCC controls, but also response between globally and peripherally enhancing CHCs, as displayed by their CT/MRI findings. OS for globally enhancing CHC group, peripherally enhancing CHC group and HCC control group were 52.8,12.4 and 67.5 months, respectively. The globally enhancing (hypervascular) group achieved a significantly higher best objective response rate than the peripherally enhancing (peripherally vascular and centrally fibrotic) group (36% vs. 0) [70]. Another study on the effectiveness of TACE in patients with unresectable CHC also demonstrated that tumor response (>50% tumor necrosis) was significantly related to its vascularity (85% response rate for hypervascular vs. 10% for hypovascular tumors) [41] . For the same reason, registration of either PEI or HAIC remains of questionable value. Despite their limited efficacy, all these methods are still tested in selected patients either for downstaging large tumors or for heavily cirrhotic patients. Ablative therapies, such as radiofrequency ablation or cryoablation, might play an important role in the management of patients with small hepatic lesions and compromised liver function ( Fig. 2 ) [21 , 45 , 46] .

Fig. 1. Diagnostic approach of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. LIRADS: Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System; LR-M: probably malignant; CC: cholangiocarcinoma; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; CHC: combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma; CA19-9: carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Concerning systemic chemotherapy, the mainstay of nonsurgical management, though standard regimens for CHC have still not been established, a broad range of chemo-agents has been tested, including gemcitabine, platinum and fluorouracil (5-FU).Data regarding efficacy of systemic agents are mainly extracted from single institutional studies. Trikalinos et al. compared therapeutic efficacy of gemcitabine containing regimens with targeted agents and liver-directed locoregional therapy (LRT) in 68 cases of unresectable or recurrent CHC. Better disease control rates (DCRs)were accomplished by gemcitabine-based regimens with higher observed progression-free survival (PFS) than sorafenib as well as the rest of systemic treatment attempts. Therapeutic performance markedly differed even between the gemcitabine-based combinations, with gemcitabine-platinum succeeding in substantially better patient response and higher DCR (78.4% vs. 38.5%) than the gemcitabine-5-FU regimen [20] . Superiority of CC-directed agent combinations over sorafenib monotherapy was also supported by two other retrospective studies. The first one evinced rapid disease progression in the sorafenib group with an OS of 3.5 months compared with the more promising results of cisplatin combinations either with gemcitabine or 5-FU (OS of 11.9 and 10.2 months,respectively) [21] . The second one similarly revealed that the gemcitabine-cisplatin regimen prevented recurrence to a greater degree than sorafenib monotherapy (PFS of 17 and 6.9 months, respectively), when applied as first-line treatments [71] . Nevertheless, in a case of HCC-predominant CHC with multiple metastatic sites, registration of sorafenib has shown favorable results [48] .This single observation, however, cannot question the superiority of CC-directed regimens and requires further investigation.

Fig. 2. Therapeutic management and alternative treatments for combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; CHC: combined hepatocellularcholangiocarcinoma; LT: liver transplantation; TACE: transarterial chemoembolization; PEI: percutaneous ethanol injection; HAIC: hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy.

Regarding future therapeutic options, integration of omics in translational research, along with the successful development of primary liver cancer-derived organoids, which retains histological and genomic features of the original tumor, constitutes a potential avenue for molecular targeted treatments. Phenotypical heterogeneity of CHC requires further investigation regarding gene expression and precision medicine applications [72] . Molecular pathways that may provide therapeutic targets include P53, PI3K-AKTmTOR, MAPK and the Notch-Hedgehog pathway [33] . The combination of atezolizumab with bevacizumab, ramucirumab and new tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as regorafenib and cabozantinib has demonstrated positive results in the management of advanced HCC. The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors, which target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) or programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), has also been tested in preclinical or clinical trials. While anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 agents combined with antiangiogenic agents constitute the most extensively tested combination regimens for advanced HCC with promising results, data on immunotherapy of CC are limited. Nevertheless, the introduction of such agents in the management of primary liver cancer may provide more potential therapeutic options also for CHC in the future [73-75] . Therefore, the enormous genetic variability still poses a major challenge for effective pharmacological treatment. Results are summarized in Table 1 .

Prognostic parameters

Prognosis of CHC is dismal. In a sample of 529 CHC patients,Ramai et al. found a median OS of 8 months as well as 1-year and 5-year cause-specific survival rates of 41.9% and 17.7%,respectively [30] . CHC is reported as an entity with either intermediate prognosis between HCC and CC [15 , 24 -27] or lower survival rate than both malignancies [17 , 23 , 42 , 44] . These results appear in survival rates measured not only after resection but also after nonsurgical management [23 , 27 , 44] .

The poor prognostic factors are tumor recurrence, tumor size>5 cm, nodal and distal metastases, age ≥60 years, microvascular,macrovascular and regional organ invasion, multifocality as well as decreased capsule formation [1 , 7 , 17 , 76 -79] . According to Zhou et al., cirrhosis also seems to reduce 5-year OS rates (34.5% in cirrhotic vs. 54.1% in non-cirrhotic patients). Nevertheless, this negative impact on survival was attributed more to post-resection hepatic insufficiency rather than the tumor itself [9] . Elevated CA19-9 and CEA levels as well as GGT>60 U/L are laboratory findings potentially associated with ominous prognosis [17 , 78 , 79] . Huang et al.also observed that radiological predominance of CC component was significantly related to less favorable median OS (15.03 vs. 40.4 months of HCC-dominant tumors). Paradoxically, the same statistical significance was not reached for the histopathological dominance of the biliary constituent [14] . This was accomplished by another study [15] . Presence of the DLK-1 homolog and>5% stemcell features are other potential pathological parameters associated with lower postoperative survival rates [80] .

As far as staging of the combined tumor is concerned, results are still inconclusive. He et al. compared suitability of many staging systems and inflammation-based scores for prognostic stratification of OS and PFS rates in both HCC and ICC-dominant CHCs.HCC-TNM exhibited the highest receiver operating characteristicvalues for all predictions and was therefore suggested as a feasible prognostic system for CHC [7] .

Table 1 Clinicopathological, diagnostic and therapeutic features of CHC divided into possibly HCC and CC-related features.

In conclusion, CHC demonstrates an overlapping clinical and biological pattern between its malignant ingredients. Natural history of the disease seems to be determined by the predominant tumor element. Despite all therapeutic attempts, prognosis of CHC remains dismal. Reported clinicopathologic prognostic parameters possibly correlated with increased tumor recurrence and grimmer survival odds include advanced age, tumor size, nodal and distal metastatic potential, vascular and regional organ invasion, multifocality, decreased capsule formation, stem-cell features detection,positivity for DLK1 homolog and increased GGT as well as CA19-9 and CEA levels.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dimitrios Schizas:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review& editing.Aikaterini Mastoraki:Conceptualization, Data curation,Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Eleni Routsi:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.Michail Papapanou:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.Dimitrios Tsapralis:Methodology, Writing - original draft.Pantelis Vassiliu:Methodology, Writing - original draft.Konstantinos Toutouzas:Methodology, Writing - original draft.Evangelos Felekouras:Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Not needed.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Non-operative management of pancreatic trauma in adults

- Torin2 overcomes sorafenib resistance via suppressing mTORC2-AKT-BAD pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells

- Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of antiviral regimens for entecavir-resistant hepatitis B: A systematic review and network meta-analysis

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Safety and efficacy of an integrated endovascular treatment strategy for early hepatic artery occlusion after liver transplantation

- Virtual navigation-guided radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma invisible on ultrasound after hepatic resection