Small-for-size syndrome in liver transplantation: Definition,pathophysiology and management

2020-09-21YuichiMasudaKazukiYoshizawaYasunariOhnoAtsuyoshiMitaAkiraShimizuYujiSoejima

Yuichi Masuda , Kazuki Yoshizawa , Yasunari Ohno , Atsuyoshi Mita , Akira Shimizu ,Yuji Soejima

Division of Gastroenterological, Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic, Transplantation and Pediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, Shinshu University School of Medicine, 3-1-1 Asahi, Matsumoto, Nagano, Japan

Keywords:

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Since the first successful adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) was reported by Makuuchi in November 1993,the procedure has become one of the treatment options for adult patients with acute and chronic end-stage liver diseases, metabolic liver-based diseases and hepatobiliary cancers [1 , 2].A graft will regenerate to the size of the recipient's initial standard liver volume(SLV) to fully meet its metabolic demands within 1 year of partial liver transplantation (LT) [3 , 4].The LDLT procedure has been widely adopted, especially in the Asian countries.In Korea, 770 adult LDLTs were performed in 2013 [5].Till the end of 2012,over 4700 LDLTs were performed in the mainland and Taiwan of China [6 , 7].And around 7500 cases of LTs in India were LDLTs between 1998 and 2015 [8].In countries, including Japan, where deceased donor liver grafts are rare, LDLTs are common and smallfor-size graft (SFSG) is not avoidable [9].SFSG usually corresponds to a graft volume of less than 0.8% of the graft-to-recipient body weight ratio (GRWR), which approximatively corresponds to 40%of the recipient's standard liver volume (SLV) based on several for-mulas [4 , 10-13 ].A partial liver graft, regardless a right or left lobe,has a potential risk of SFSG.

The chances to obtain a deceased donor graft are more often in Western world than those in the Asian world.A split LT can occasionally be safely performed for two recipients [ 14-17 ].In such cases, the use of a partial graft in adult LT might also result in a smaller-than-required volume of graft to meet the expected metabolic demands.

It was reported that a minimum remnant of 20%-35% of the total liver volume is required to maintain patients' metabolic demands after partial liver resection; these percentages may change in accordance with the patients' conditions [ 18-23 ].Based on this knowledge, 30%-35% of a recipient's SLV or 0.6%-0.8% of GRWR was thought to be the minimum size of liver graft for a successful LDLT [24 , 25].Nevertheless, a successful adult LDLT using a very small graft (with 25% of the recipient's SLV or 0.6% of GRWR)has prompted an ongoing debate about the minimally required liver graft volume [24 , 26-32 ].With increasing partial LT cases performed in adult recipients, transplant physicians are expected to encounter “small-for-size”syndrome (SFSS) as a post-operative complication.The use of SFSG itself holds a risk for SFSS which in fact is a multi-factorial event; these risk factors of SFSS include preoperative patient condition, surgical technique, and graft quality and size.This review covers the definition, clinical symptoms,pathophysiology, basic research, as well as preventive and treatment strategies of SFSS based on an extensive personal experience and the English literature.

Data sources

The data were collected from PubMed.The search terms included: “liver transplantation”, “living donor liver transplantation”, “living liver donation”, “partial graft”, “small-for-size graft”,“small-for-size syndrome”, “graft volume”, “remnant liver”, “standard liver volume”, “graft to recipient body weight ratio”, “sarcopenia”, “porcine”, “swine”, and “rat”.English papers published during the period from 1969 to March 31, 2020 were included in this review.

Definition

The definition of SFSS varies among studies (Table 1) [33-39].In 2003, Soejima et al.defined the criteria of SFSS [33]to be inclusive of a total bilirubin (TBil) level>5 mg/dL (which was subsequently changed to 10 mg/dL [35]) at post-operative day (POD) 14,as well as ascites more than 1 L at POD 14 or more than 500 mL at POD 28.They divided 36 liver recipients into two groups based on the criteria and compared their demographics.Patients with cirrhosis had significantly higher incidence of SFSS.Patients with SFSS(n= 8, 22.2%) showed relatively lower graft survival rate in comparison to those without SFSS (P= 0.07).

In 2005, Dahm et al.proposed another definition of small-forsize (SFS) dysfunction and SFS non-function occurring within the first post-operative week [34].The recipients having technical [e.g.,vascular thrombosis, venous outflow obstruction (and thus congestion), or bile leak], immunological (e.g., rejection), and infectious (cholangitis and sepsis) problems were excluded.SFS dysfunction was assigned to those who received a GRWR<0.8% graft(a ”small”partial liver graft) and had two of the following clinical presentations for three consecutive days: TBil>100μmol/L; international normalized ratio (INR)>2; and encephalopathy grade 3 or 4.SFS non-function was assigned to those who received a GRWR<0.8% graft but required re-transplantation or died.

Clinical manifestations

SFSS is characterized by long-lasting massive ascites (>1 L), hyperbilirubinemia, coagulopathy and encephalopathy grade 3 or 4.Other symptoms, such as sepsis, pre-renal insufficiency, gastrointestinal dysfunction (ileus), and/or bleeding, are also observed.Patients with SFSS have a longer recovery period compared to those without SFSS.These symptoms can disappear under optimal conservative treatment, such as intensive fluid management (including albumin administration), infection control and nutritional supplementation.The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates in SFSS patients(74.1%, 67.9%, and 67.9%, respectively) can be comparable to those of patients without SFSS (83.5%, 79.7% and 77.0%, respectively) [40].

Pathophysiology

Emond et al.initially reported the pathological findings of biopsy specimens from five LDLT recipients at POD 7 and 14 [41].The biopsy specimens of the five recipients who received a graft with 23% -44% of their SLVs revealed ischemia, cholestasis, and regeneration.The authors described the changes seen at POD 7 specimens as “a diffuse ischemic pattern with cellular ballooning”.Cholestasis developed at POD 14 as diagnosed by liver biopsies.The early graft function of these recipients was significantly decreased.

Demetris et al.also reported the early and late pathological features of SFSS of five patients who were diagnosed with portal vein (PV) hyper-perfusion or SFSS [42].The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score and GRWR were 8-19 and 0.6% -1.4%,respectively.PV endothelial damage, centrilobular microvesicular steatosis and cholestasis with hepatocytes ballooning and ductular reaction were observed in the specimens 3-10 days post transplantation.Arterial vasospasm and thrombosis as well as bile duct necrosis were seen in the biopsies taken 10 to 20 days posttransplantation; later on (beyond POD 20) nodular regenerative hyperplasia was diagnosed.

Regarding the molecular pathophysiology in SFSG, the gene expression was investigated in animal model in the same lab [ 43-45 ].They found that endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor, was overexpressed in the grafts.The excessive expression of endothelin-1 can cause constriction of the hepatic sinusoids and disturb the microcirculation in the graft, thereby increasing the PV pressure.Moreover, the gene expression of the anti-oxidative stress proteins heme oxygenase-1 and heat shock protein 70 was significantly decreased in SFSG, inducing ischemia and rendering the hepatocytes vulnerable to the subsequent oxidative stress.Other changes, such as down-regulation of A20, up-regulation of early growth response protein 1, and over-expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase,may also exacerbate the inflammation in the graft liver.The summative effect from the hepatocytes loss resulting from these conditions may contribute to the pathogenesis of SFSS.

SFSS also develops in case a whole liver graft with adequate functional liver volume is used for transplantation.In Asian countries however, the chance of obtaining a whole graft from a deceased donor is very limited.Therefore LDLT using (relatively)small grafts is common and size mismatched grafts are transplanted [24].It is now widely accepted to use grafts with more than 30% -35% of the recipient's SLV or 0.6% -0.8% GRWR in LDLT [10 , 25 , 36 , 46].However, these values are the minimal accepted volume ranges that may meet the recipient's metabolic demands.In case “small”grafts are used, portal hypertension and/or excessive portal flow is encountered.The control of the PV pressure is one of the key factors to overcome SFSS [47].

Kiuchi et al.reported that the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) status 1 patients who received grafts with GRWR<0.8% grafts from older donors (>50 years old) had a lower graftsurvival rate [48].Previously, the Kyoto group also identified the impact of the graft size (<1% GRWR) and portal venous pressure (≥20 mmHg) on post-transplant outcome [24 , 49].Ito et al.reported a splenic artery ligation technique to reduce PV pressure [49].Among the patients who received grafts with 0.8%GRWR in the study, those with an elevated mean PV pressure(≥20 mmHg) demonstrated significantly worse survival, bacteremia, cholestasis, prolonged prothrombin time, and ascites.The use of the splenic artery ligation technique lowered the PV pressure by 11 mmHg (median) and allowed to improve the survival rate.

Table 1The definition of small-for-size syndrome *reported by various authors.

The same group described another method to reduce PV pressure in 134 patients [50].With the transplantation of significantly smaller grafts [from 1.15% (previously) to 0.92% GRWR]for those with higher MELD scores [from 19.4 (previously) to 22.9 points],the authors managed to improve patients' survival.They monitored PV pressure in 129 patients out of 134 patients.A total of 126 patients (97.7%) achieved the targeted PV pressure of below 20 mmHg, mainly through splenectomy.The patients with PV pressure ≥ 15 mmHg, in comparison to those with PV pressure<15 mmHg after revascularization had significantly worse outcomes in one-year (73% vs.95.2%) and two-year (66.3% vs.93.0%) survival rates.In addition, they also exhibited higher levels of TBil,INR, and volumes of ascites.With the aforementioned strategy, the Kyoto group successfully changed the graft acceptance criteria towards the ≥0.6% GRWR value, with an improvement of patient outcome [25].

On the other hand, the Juntendo University group (Tokyo,Japan) used only left liver grafts ranging from 26.1% to 47.6% of the recipient's SLV; this group reported 100% one-year survival rate without any portal inflow modulation [51 , 52].However, they mentioned that PV inflow modulation might be required to improve the early outcome for patients with PV pressure exceeding 25 mmHg after implantation.

According to the meta-analysis by Yan et al.the patient outcome with SFSS was comparable to that without SFSS since 2010 [53].

Basic research

In 1995, Yanaga et al.used a porcine partial LT model and demonstrated that if the graft was less than 30% of the whole liver volume, the animals could not survive [54].The histological findings included congestion, necrosis, and severe endothelial cell denudation which are corresponded with those seen in human SFSS studies.

Kelly et al.added immunosuppressive drugs, such as tacrolimus and methyl prednisone, to the SFS pig liver graft model [55].The authors demonstrated that all the animals that received a graft corresponding to more or equal to 30% of the recipient's native liver volume survived for five days.The mortality rate of the animals which received grafts corresponding to 20% of their native liver was 47%.Clinical manifestations of SFSS, such as hyperbilirubinemia, prolonged prothrombin time, and ascites, were present in all survived animals received a graft of 20% of native liver volume.The histological findings of liver grafts receiving less than 30% of their native liver again showed moderate to severe congestive hemorrhage and endothelial detachment as early as five minutes after reperfusion.

Asakura et al.and Wang et al.introduced portocaval shunts to address the graft damage caused by excessive portal venous flow [ 56-58 ].Hessheimer et al.reported that the optimal portal venous flow in SFSG pig model using portocaval shunt was about twice its baseline value [59].Unfortunately, pig models were not available to reproduce and validate the studies related to the effi-cacy of splenic artery ligation or splenectomy to modulate the portal flow [60].

Hessheimer et al.demonstrated that somatostatin administration in the pig 20% graft model reduced the portal flow at reperfusion and improved graft histology [61].According to their recent review paper, they introduced the clinical use of somatostatin therapy to reduce excessive portal venous flow and hepatic venous pressure gradient in the post-hepatectomy setting [62].They also used somatostatin in their institution and successfully reduced the post-hepatectomy liver failure rate from 9% to 2%.In the LT setting, Lee et al.and Troisi et al.reported the effectiveness ofsomatostatin to reduce ascites production and PV pressure in LT recipients [63 , 64].Kelly et al.also showed the effectiveness of adenosine in maintaining arterial flow as well as improving graft histology and survival rate [65].

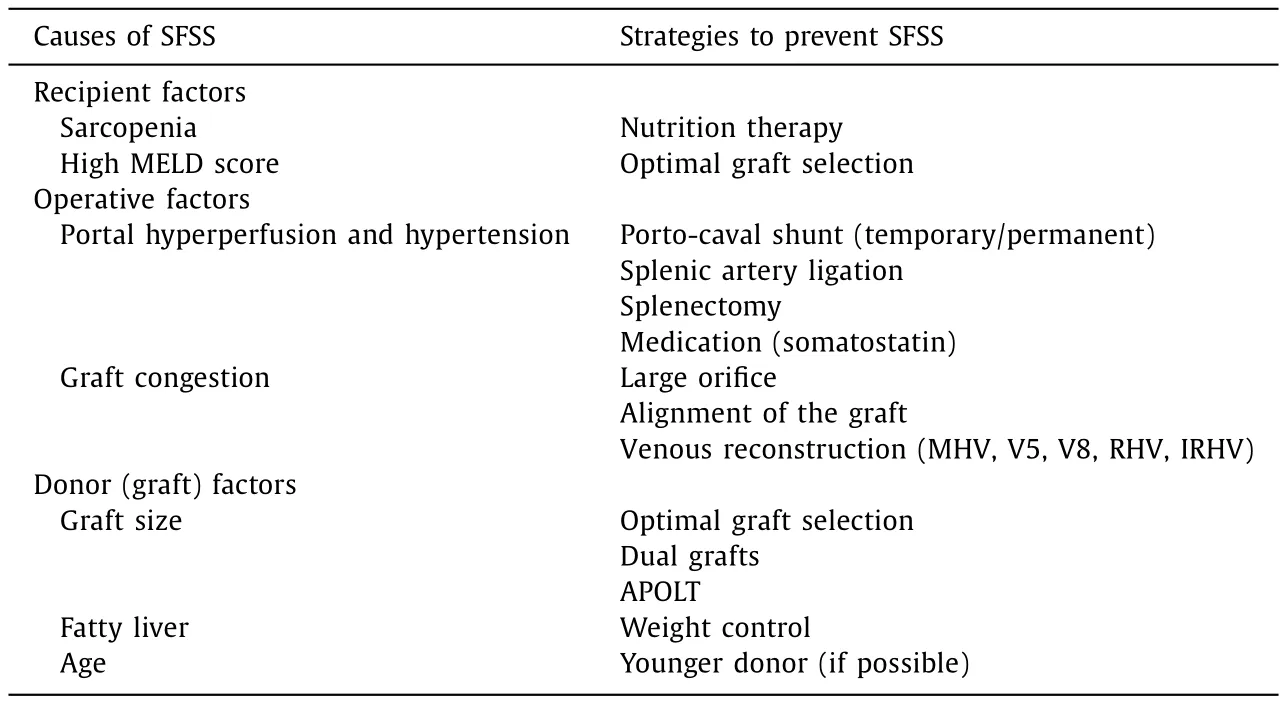

Table 2The causes of SFSS and the strategies to prevent SFSS.

Many rat LT models have also been studied in relation to the SFSS.Liang et al.and Man et al.revealed endothelin-1 mRNA upregulation in SFSG [43 -45].Recently, Yoichi et al.illustrated the effect of splenectomy in a rat LT model in terms of improvement on graft histology, serum bilirubin and ALT levels, as well as reduction in endothelin-1 mRNA expression [66].Steatosis is known to aggravate graft function and many agents have been proven to reduce ischemic reperfusion injury on rat liver [ 67-70 ].The reduction of liver injury may contribute to reducing the functional hepatocyte volume and to preventing recipients from SFSS.

Strategies to prevent SFSS (Table 2)

One method to prevent SFSS is of course to transplant an acceptable graft in terms of size and function.In 2017, a guideline was published from the International Liver Transplantation Society, encompassing three recommendations of Class 1 evidence(STRONG) in order to prevent SFSS [28].The first is “graft injury and dysfunction in SFSS is not only a reflection of graft size but also of graft quality and degree of recipient portal hypertension causing graft hyper perfusion”.The second is “monitoring of the portal vein and hepatic artery hemodynamics is highly recommended for the early diagnosis, prevention and management of SFSS”.The third is “portal inflow modulation by splenic artery ligation/embolization or other portosystemic shunts is effective in the prevention and treatment of SFSS”.It is very crucial to maintain large hepatic venous drainage for the outflow.

Surgical technique(s)

Portalflowmodulation

Many studies looked at PV pressure reduction using splenic artery ligation.Troisi et al.compared the PV flow between donors and recipients and found that the PV flow in the recipients were significantly higher [71].PV flow and PV flow/graft weight could be reduced by ligating the splenic artery; this also led to lower complications such as vascular thrombosis and intractable ascites.They proposed to reduce the PV flow using splenic artery ligation of less than 250 mL/min per gram of the graft.Ito et al.managed to reduce 11 mmHg of mean PV pressure using the same technique [49].They ligated the splenic artery in patients receiving less than 1.0% GRWR graft or with ≥20 mmHg of PV pressure.

The use of splenectomy as an effective therapeutic option to modulate PV flow and overcome SFSS has been well described by Yoshizumi et al., who performed splenectomy in patients with ≥20 mmHg of PV pressure after reperfusion, and with low white blood cell count (<20 0 0 /mm3) and platelet count(<30 0 0 0 /mm3) [72].However, it should be noted that by doing so, a risk of PV thrombosis and overwhelming post-splenectomy syndrome exists [73].

Port-systemic shunt has been proposed as an effective surgical option to reduce the incidence of SFSS [ 74-82 ].According to the literature, this technique was applied to patients who received a graft with less than 0.8% of GRWR or with ≥20 mmHg of PV pressure.However, graft atrophy was observed in a case of portocaval shunt surgery due to hemodynamic changes after LT [83].It is also unclear whether the shunt should be maintained or closed in a later period after LT.

Outflowreconstruction

Any allograft congestion should be cleared in order to optimize the potential graft function.Several studies explored surgical techniques to avoid graft congestion, especially in case right liver graft without the middle hepatic vein was used [ 84-92 ].The umbilical,internal jugular, iliac, saphenous veins, and PV procured from explanted liver, and cryopreserved graft have all been used to reconstruct the hepatic venous outflow of the graft.Such reconstruction is also beneficial when using a graft presenting a large (>5 mm)inferior right hepatic vein [87].

Graftvolume

Patients with higher MELD scores might need a larger graft at least for the early post-transplant period [93].From past experiences, the minimum requirement for a liver graft is considered to be at 30% -35% of the recipient's SLV.However, as the minimum graft volume to prevent SFSS is still controversial, every effort to minimize the risk of donor should be taken [94 , 95].

Ikegami et al.studied 120 cases of left LDLTs without portal flow modulation [96].The cohort was divided into two groups according to the graft size, one having a graft of less than 35% of a recipient's SLV and the other more than 35%.Complying with the definition of SFS dysfunction proposed by Dahm et al., only one patient developed SFSS, but that patient was in larger graft group.There was no significant difference in the massive ascites production and prolonged cholestasis between the groups.Six patients in the smaller graft group, including two (33%) sepsis cases, died within one year post-transplant.Eight patients in the larger graft group died within the first post-LT year, but none of them died of sepsis.These results are in accordance to the causes of death reported for SFSS.

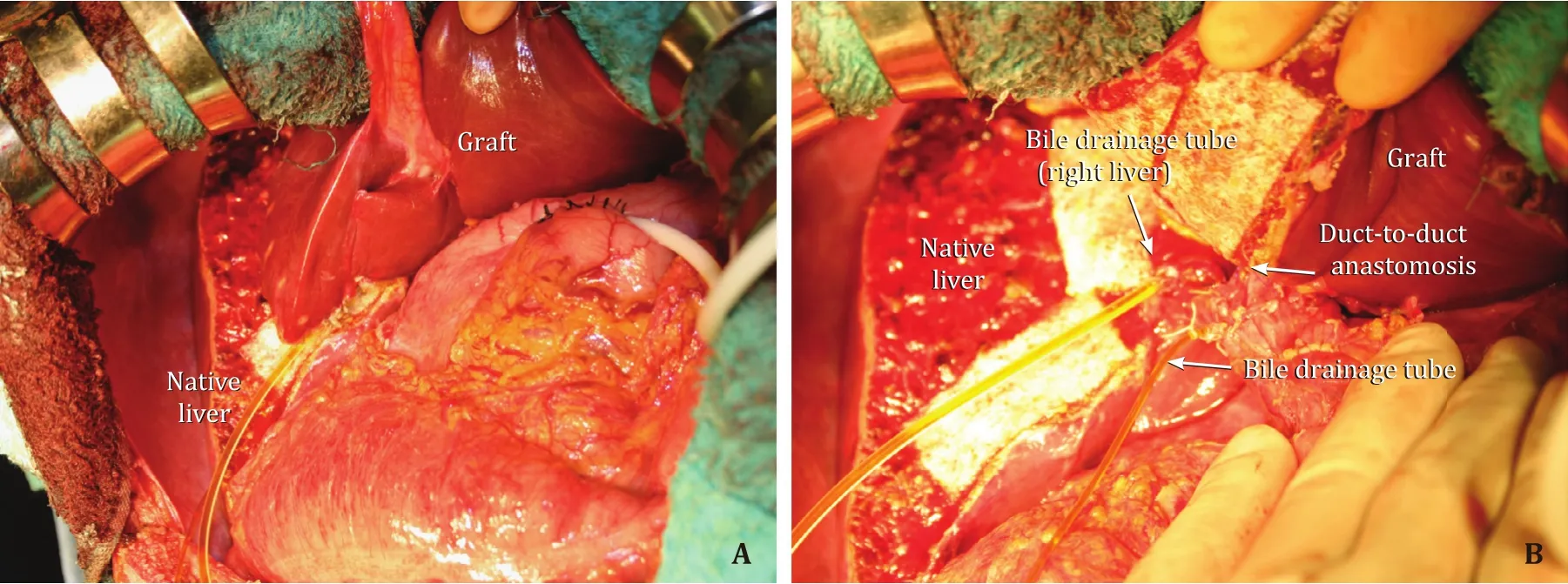

Fig.1.A: A case of auxiliary partial orthotropic liver transplantation.The left liver graft weighted 340 g, that corresponded to 33.0% of recipient SLV; B: Hepatic hilum.The left hepatic duct of the graft to the recipient common hepatic duct anastomosis was performed.The bile drainage tube was inserted through the cystic duct of the recipient into the graft, and another bile drainage tube was inserted into the right hepatic duct.SLV: standard liver volume.

Kurihara et al.made their graft selection based on parameters previously reported by Yoshizumi et al.such as graft volume, donor age, and MELD score.The outcomes in the severely ill patients were excellent and comparable, independent of the use of a leftor right-lobe graft [97 , 98].

Auxiliarypartialorthotropiclivertransplantation(APOLT)

APOLT is another surgical option to meet metabolic demands while avoiding SFSS, in patients with metabolic liver-based diseases such as familial amyloid polyneuropathy, adult-onset type 2 citrullinemia, and other urea cycle disorders (Fig.1) [ 99-103 ].As most of these diseases are hereditary, selection of relative donors should be stringent to assure donors' safety.Additionally, incidences of graft portal steal phenomenon and symptoms of recurrence of primary diseases should be carefully monitored [104].

DualgraftsLT

A radical solution to the SFSG problem lies in the use of two grafts from two different donors for one recipient in the dual grafts LT procedure [ 105-109 ].This dual graft LDLT technique has produced good outcomes, both in relation to recipient survival and donor safety.

Recipient condition and donor factor(s)

Recipientcondition

It is important to improve the perioperative conditions of the recipients through nutrition therapy, in order to minimize the incidence of sepsis and improve outcome in SFSS recipients [ 110-113 ].Masuda et al.reported that the incidence of sepsis was significantly decreased in recipients with sarcopenia after induction of nutritional therapy [113].Kaido et al.measured the body composition, such as skeletal muscle, bone, and intracellular water, using multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analysis (In-Body 720; Biospace, Tokyo, Japan) in 124 LDLT recipients, and defined the recipients with less than 90% of standard skeletal muscle mass as low skeletal muscle recipient (n= 47) [110].In their institution, the preoperative nutritional therapy, a nutrient mixture enriched with branched-chain amino acids, a supplementation product enriched with glutamine, dietary fiber and oligosaccharide, a lactic fermented beverage containinglactobacilluscasei, and polaprezinc were administrated to the recipients two weeks before LDLT.The enteral tube nutrition was started using hydrolyzed whey peptide within 24 h after LDLT and was changed to oral nutrition according to the recipients' status.They reported that the patient survival rate was significantly improved in recipients diagnosed as having low skeletal muscle mass and received perioperative nutritional therapy.

Donorfactors

It is well documented that an aged donor graft can affect the recipient's outcome.A donor's age of more than 60 years was reported as one of the factors that negatively impact a patient's survival [114].Yoshizumi et al.also demonstrated that the levels of TBil and volume of ascites were significantly lower in the donor age<50 years group among their left LT patients [115].Macshut et al.reported that donor age over 45 years was an independent risk factor for SFSS [116].Hence, younger donors should be selected whenever possible for patients who are more critically ill.

A fatty liver graft can increase the prevalence and severity of ischemic reperfusion injury as well as risk of primary nonfunction [ 117-119 ].As a result, a program to safely reduce the weight and degree of fatty liver in donors has been introduced successfully [120].

Treatment

Ultimately, conservative treatments, such as aggressive fluid balance correction, including intensified albumin administration for massive ascites, anti-microbiological therapy for sepsis, and nutritional therapy, are all of importance to reduce or prevent the development of SFSS.

Summary

SFSS is still a real clinical problem occurring in all modalities of partial LT.Besides SFSG, the development of SFSS is influenced by many factors, such as the recipient's condition, graft quality, and surgical technique.A surgical approach, to control portal venous flow and pressure is very important to prevent SFSS, especially in severely ill recipients.Unfortunately, there is currently no medication available to resolve the SFSS problem.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuichi Masuda:Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft.Kazuki Yoshizawa:Data curation.Yasunari Ohno:Data curation, Formal analysis.Atsuyoshi Mita:Data curation.Akira Shimizu:Data curation.Yuji Soejima:Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Not needed.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Recent evolution of living donor liver transplantation at Kyoto University: How to achieve a one-year overall survival rate of 99%?

- Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation with or without sphincterotomy for large bile duct stones removal: Short-term and long-tem outcomes

- Optimizing biliary outcomes in living donor liver transplantation:Evolution towards standardization in a high-volume center

- Hepatic vein in living donor liver transplantation

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Hepatic artery reconstruction in pediatric liver transplantation:Experience from a single group