那簇火,映红过江南的天空

2020-07-20陈荣力

陈荣力

像破岩的地火苏醒复活,那簇火在越州的苍山翠岭间荧光焯焯;

如熊熊的火炬燎原接力,那簇火在浙东的曹娥江两岸烈焰赤赤;

似劈云的闪电涅槃新生,那簇火映红江南一千余年的天空生生不息。

一

我是在大园坪青瓷窑址挖掘即将进入尾声时,走进位于浙东上虞上浦镇四峰山大园坪窑址挖掘现场的。

那时,江南的田野里稻穗已经灌浆, 村口的桂花尚未隐去最后一缕甜香,除银杏和乌桕开始泛黄、转红外,浓绿和深绿依然是四峰山的主宰。满目的葱茏中,远远眺望四峰山南坡大园坪窑址黄土裸露的挖掘现场,恰如一件绿色的军装上别了一枚黄色的徽章。这样的发现和比喻,也让主持大园坪窑址挖掘现场的省考古所专家郑先生来了兴致。

“是的,窑址也可看作是青瓷的一枚徽章。它浓缩了青瓷发展的历史和变革,凝结了烧制技术的成就和创新,既是一种记载,更是一种见证。”考古工作和长年野外生活的艰苦单调,并没有让郑先生变得木讷和刻板,相反,他的交谈和讲述生动风趣,充满了专业的机智。随着郑先生话题的打开,曾轰动青瓷考古界的大园坪青瓷窑址的神秘面纱,在我面前徐徐撩开。

位于四峰山南坡的大园坪窑址,属东汉晚期青瓷窑址。大园坪窑址暴露出来的青瓷片堆积层厚达40厘米,所见的器型,几乎包括了东汉窑址常见的青瓷器型,洗、罐、碗、钵、瓶、瓿、罍、锺、坛、虎子等一应俱全。胎色灰白、质地坚硬紧密、击打时发声清亮的大园坪窑址青瓷,釉色青绿、青灰,釉层厚实,釉面莹润光洁,极少剥釉、起泡、变形等现象发生。而弦纹、水波汶、菱形纹、直线纹、网纹、布纹、叶脉纹和贴印铺首、爬虫等的印划、镂贴等,更是集东汉青瓷纹饰之大成。

郑先生对大园坪青瓷窑址专业又通俗的解读,指向一个权威的结论:大园坪是迄今为止发现的东汉窑址中技术最先进、功能最完备,烧制的青瓷器型最全、质量最好、纹饰也最丰富的青瓷窑址。换句话说,大园坪作为东汉青瓷窑址的杰出代表,当之无愧,意义重大。亦因此, 大园坪窑址和毗邻的小仙坛、小陆岙窑址一起,被列为全国第六批重点文物保护单位。

问及大园坪青瓷窑址之所以能有如此成就的主要原因时,郑先生灿然一笑:“关键就一个字:火。”

大园坪窑址发掘的另一重要成果,是两条龙窑被揭露。尤其是一号龙窑,残长6.36米,宽1.80米,火膛、窑室、排烟坑三大核心部分保留完整。据推测,一号龙窑全长应在13米左右,其窑室残长尚有5.2米,宽2.2米,火膛后壁高0.6米。

“如此构造和规模的龙窑,在当时无疑是最先进的,也足见那时青瓷工匠们的聪明和智慧。”郑先生意犹未尽,“龙窑的最大贡献,是解决了火,即青瓷烧制的温度问题。从陶到原始青瓷,再到成熟青瓷,虽然成功的因素很多,但一个关键的因素就是烧制的温度。龙窑的发明和成熟,将原来立窑、馒头窑摄氏800~900度的温度,一下子提高到摄氏1100~1200度,而大园坪的一号龙窑,据推测烧制的温度可达摄氏1300度左右。”

“这真是一簇神奇的火,智慧的火,也是一簇美妙的火啊!”离开大园坪时,郑先生站在夕阳映照的大园坪,巡望四周隐约可见的小仙坛、大平地、大湖岙、白沙湾等众多窑址,忍不住感叹。

那次走进大园坪窑址挖掘现场,是2004年的事,屈指算来,距今已十五六年,但每每想及郑先生的感叹,总令人怦然心动,不胜神往。

二

藉了这样一份心动和神往,这些年来走访、探寻浙东上虞、绍兴、慈溪一带的东汉、两晋、南北朝以及隋、唐等各个时期的青瓷窑址,成了我的一大爱好。

在以窑址群密集著称的大湖岙窑址、米夹岙、大树山、前山、官山、捣臼窝等十几处窑址,星罗棋布,此迭彼延;在以萌发秘色瓷闻名的上林湖窑址,翡翠般的瓷片逶逦铺展,与清澈的湖水融连一片;在山峦起伏田畴阡陌的帐子山窑址,山脚、路边、沟渠、岭畔,一不小心你就会踢着一片古瓷,被半拉窑具磕绊;在列为2014年全国十大考古发现的禁山窑址,东汉、西晋、东晋等多个时期的窑址依次排列,状态典型,恰如打开一卷青瓷发展的史书。这样的走访和探寻,也让我对那簇火,对那簇曾映红过江南1000余年天空的窑火,有了感性的认知和诗意的品读。

众多研究资料表明,由新石器时代问世的陶,进入商周即已具原始青瓷的雏形。东汉以降,随着人口的增多、交往的扩大和生产的发展,釉彩等制作水平进一步提升,特别是随着龙窑技术的提升,烧制温度的突破,东汉中期成熟青瓷开始在浙东上虞一带出现。

任何物质文明的问世,既是时代和社会的产物,也必定成为其进步和发展的密码。坚固耐用、造型精美、器皿丰富、色泽鲜亮的成熟青瓷一经问世,便迅速替代笨重、粗陋、暗黝又易碎的陶器和原始青瓷,成为上至庙堂下至黎庶的最爱。“曹娥江上百舸争流,白帆如云;会稽山麓千窑林立,青烟拢日。”那不啻于一场制造业革命的青瓷浪潮,以浙东上虞一带为核心,波漫江南,浪击全国,其美妙的水花甚至溅及东南亚、日本、朝鲜和欧州。据统计,仅在浙东上虞,已探明有确定地址和名称的自东汉至北宋各个时期的青瓷窑址便达158处。

作为世界青瓷发源地的浙东上虞,东汉中期成熟青瓷之所以发端于此,仔细想来绝非偶然。上虞乃河姆渡文化的中心区域,新石器时代后期即有烧制陶器的历史,曹娥江、小舜江便利的水运条件,会稽山、四明山独特的瓷土资源和林木茂密的燃料支撑,这些都为成熟青瓷烧制的滥觞和繁荣提供了物质保障。而物质之外的人,点燃那簇窑火,让其蔓延、燎原,让其生生不息映红江南一千余年天空的青瓷窑工们,更是点土成金的精神动能,决定兴衰成败的关键主因。

在走访、探寻众多窑址中,有一个问题总让我纠结:由原始的立窑和馒头窑改为先进的龙窑,如此的脱胎换骨到底是因了怎样的启迪?这样的推陈出新又缘于怎样的魔力?一次,在走访帐子山窑址时,一位八十多岁的老者向我讲述了一個美丽的传说。

东汉早期,曹娥江中游的四峰山、帐子山、拗花山一带,已是原始青瓷的主要产地。然而因工艺陈旧,烧制温度无法突破,原始青瓷销售困顿,窑工生活艰难。有一位叫谢胜的窑工勤劳聪明,烧制技术更是一把好手,是窑工们的主心骨。为了提高烧制温度,谢胜扒了小窑建大窑,拆了老窑造新窑,但总不见有大的起色。一天凌晨,电闪雷鸣,一场初夏的雷暴雨骤然而至。雨停了,天也亮了,谢胜早早来到位于半山坡的窑场。但见窑场对面两峰相夹的山岙间,一股白色的水雾似一条巨龙,从山脚向山顶滚涌、升腾,巨龙所到之处,树叶树杈杂草纷纷裹挟而上。谢胜先是出神地看着,突然,他一下醒悟,兴奋得手舞足蹈、大喊大叫。不久后一座依山坡而建的卧窑,出现在窑工们面前。

開窑的时刻是慌恐和亢奋的,为这座新窑耗透了心血的谢胜,更是紧张得近乎窒息。窑门终于打开了,一片翠绿的荧光从窑内射出,谢胜惊呆了,众人惊呆了, 那热浪尚存的窑室里,分明是一窑通体翠绿、莹光锃亮的碧玉啊! 那座依山坡而建的卧窑, 恰似一条顺坡向上游动的蛟龙啊!于是,谢胜和窑工们便把它称为龙窑。

传说固然是一种美好的寄托,但透过这种寄托,我们分明可以悟到一个朴素的哲理:任何物质文明的诞生和发展,都离不了自然界的恩赐,就像机遇和成功是留给有准备的人一样,敬畏自然、亲近自然,善于从气象万千、美妙神奇的自然界汲取智慧和力量,又何尝不是一种厚积薄发的机遇和天人合一的成功呢!

龙窑的出现,对成熟青瓷的烧制无疑具有划时代的意义。这样的划时代,既在于窑的形态的创新和颠覆,更缘于火的交响,由此,青瓷奏响了最瑰丽的乐章。

三

在人类的进化史和文明发展史中,火的意义和作用不言自喻。火既是人类集体的智慧,也是共同的成果。然而在不同的地域、各异的文化中,同样的火分明又跃动着各自缤纷的形态,熔铸出异彩纷呈的硕果。如果说,西方的火催生了机器和工业革命,中原的火诞生了雄浑庄重的青铜器,那么在温山软水的江南,在稻香鱼肥的浙东,千峰翠色的青瓷,端的是火谱写的绿色诗篇、结晶的碧莹花朵。

总以为那簇火,那簇映红了江南一千余年天空的窑火,于江南、于浙东,是一种天生的宿命和不朽的传奇。因了那簇火,平常的泥和水升华为精美坚固的器皿精灵;缘了那簇火,千山的苍翠万水的秀色涅槃成美轮美奂的永生;凭了那簇火,水样柔曼的江南熔铸进格物事工的求实和勇立潮头的坚韧;仗了那簇火,一方地域更锻打出五千年文明古国走向世界的物质徽章和文化图腾。

那簇火是汗水是执着,那簇火是智慧是开拓,那簇火是一块叫江南、叫浙东的土地生命的诗意和精神的大纛!

那簇火,注定了要生生不息。

Celadon: Finest Porcelain Born in Fire

By Chen Rongli

It was in 2004 that I visited the excavation site at Dayuanping where archaeologists were exploring the remains of two ancient dragon kilns. The archaeological project was drawing to its end. Dayuanping is in Shangpu Town, Shangyu, which is now a district of Shaoxing in eastern Zhejiang.

The discoveries from the site caused a sensation among archaeologists and celadon experts in the province for two major reasons.

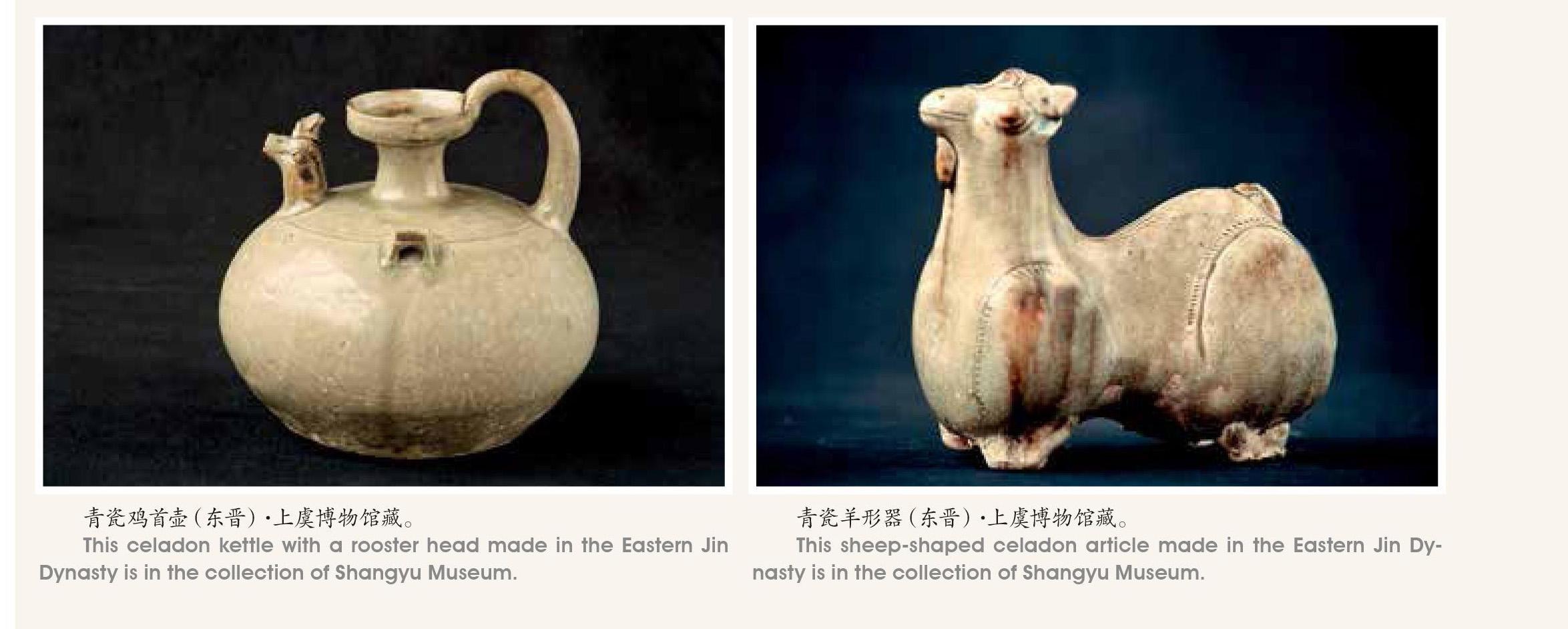

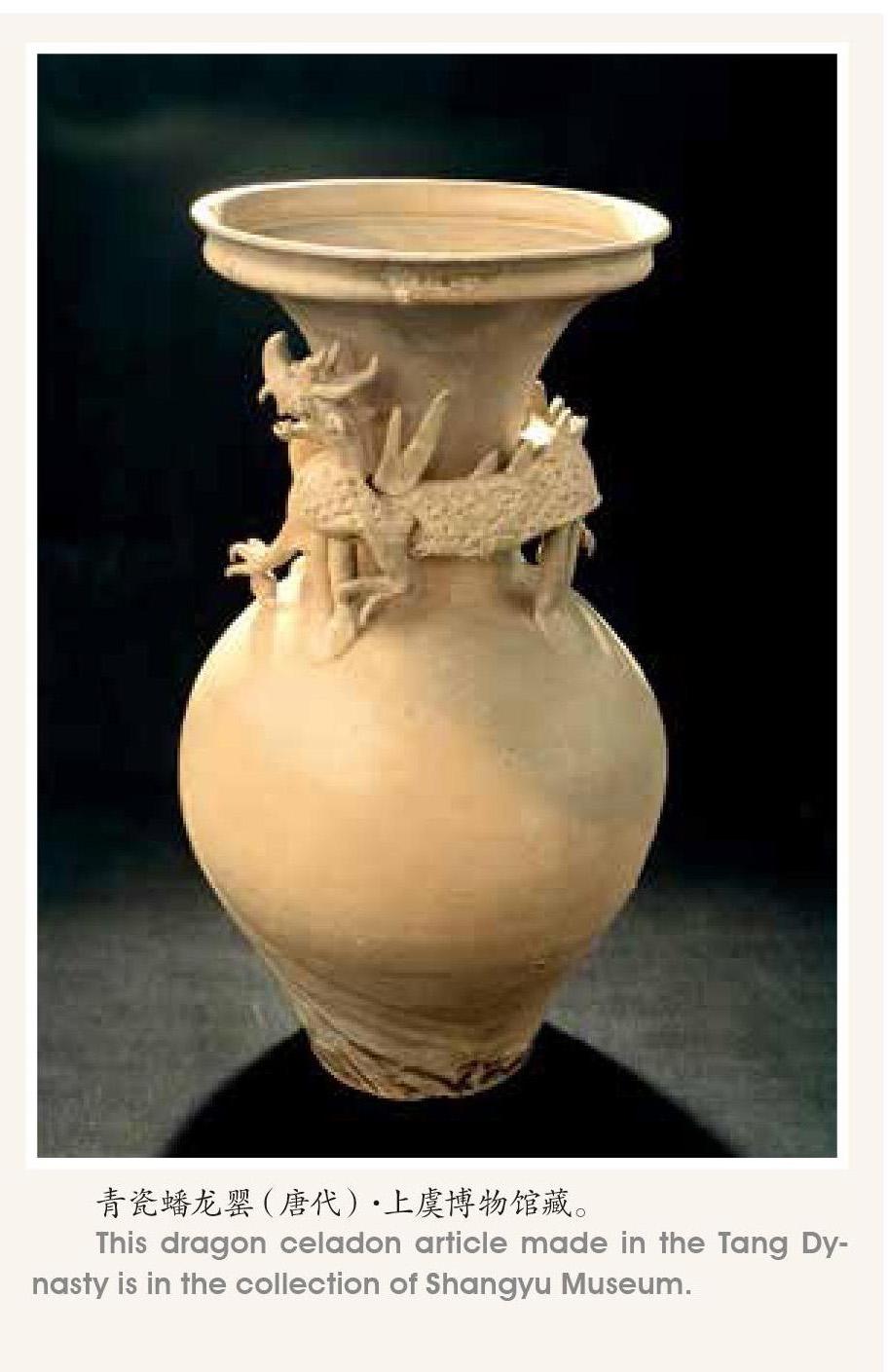

First, the two dragon kilns date back to the last decades of the Eastern Han (25-220AD). A 40-centimeter-thick layer of celadon shards at the Dayuanping site indicates that the shards are from a full range of celadon utensils seen at all other Eastern Han kiln sites. The clay bodies and glazes suggest a fine craftsmanship rarely seen anywhere else. The clay bodies are solid and give clear and clean sounds when tapped lightly. Glazes on the clay bodies are smooth, bright and clean. The decorative patterns on these shards are an encyclopedia on the celadon designs of the period. In fact, the ancient kilns at Dayuanping represent the best celadon kilns of the era in terms of advanced technology and full function. The celadon shards unearthed there represent the best quality and best range of utensils and best patterns ever seen in the period. The kilns at Dayuanping and two adjacent ancient kiln sites were placed under the national governmental protection in May 2006.

Secondly, the firing technique used at the celadon kilns at Dayuanping explains why the site is so important. Dragon kiln number one, truncated by disuse, damage, and time, is 6.36 meters long and 1.80 meters wide. The fire chamber, the ware chamber, and the chimney pit are well preserved. It is estimated that the original dragon kiln was about 13 meters long. The dragon kiln of this scale and structure represented the best technology of the time. Generally, dragon kilns were able to raise firing temperatures to 1,100 to 1,200 degrees Celsius. The standing kiln and the bun-shaped kiln could only achieve a temperature of 800 to 900 degrees Celsius. Studies indicate that dragon kiln number one at Dayuanping could operate at a temperature of 1,300 degrees Celsius. The higher temperature, as testified by the dragon kiln, made the difference.

The visit to Dayuanping opened my eyes to the ancient kilns in Shangyu and enabled me to understand the importance of these kilns in the history of porcelain making in Zhejiang.

Researches indicate that the pottery which emerged in the Neolithic Age became primitive celadon in the Shang (c. 1,600-1,046 BC) and the Zhou dynasties (1046-221 BC). In the Eastern Han, porcelain making became advanced as porcelain clay, utensil shapes, and glazes became better. Dragon kilns revolutionized porcelain making. During the middle period of the Eastern Han, kilns in present-day Shangyu were able to produce exquisite celadons.

The porcelain making industry boomed, replacing the pottery and primitive celadons. The technology and products spread to four corners of the country and reached overseas. Now we know the names and sites of at least 158 kilns in Shangyu that existed from the Eastern Han to the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127).

It was no accident that celadon took shape in Shangyu in the middle period of the Eastern Han. Shangyu was in the heartland of Hemudu Culture, which flourished (5,500BC to 3,300BC) just south of the Hangzhou Bay in Zhejiang Province. In the late period of the Neolithic Age, pottery making was abundant in the region thanks to rich resources made available by rivers that crossed Shangyu.

No one knows exactly how the first dragon kiln appeared in the history, but local enthusiasts never hesitated to create a story to explain the turning point in the history of porcelain making. I heard a folktale from an old man in his 80s during a field study. According to the old man, a young master was inspired by a dragon-like cloud surging out of a valley during a storm and instantly knew exactly what to do. He built a dragon kiln stretching long upward on a hill slope. The dragon kiln produced the finest porcelain never seen before. It is hard to say whether the revolutionary technology appeared thanks to an epiphany on a stormy day or took form painstakingly bit by bit due to efforts made by craftsmen for better productivity and quality over a long period of time.