Stability and nonlinear vibrations of a flexible pipe parametrically excited by an internal varying flow density

2020-05-06XieGaoXu

W. D. Xie·X. F. Gao·W. H. Xu

Abstract Pipes are often used to transport multiphase flows in many engineering applications. The total fluid flow density inside a pipe may vary with time and space. In this paper, a simply supported pipe conveying a variable density flow is modeled theoretically,and its stability and nonlinear vibrations are investigated in detail.The variation of the flow density is simulated using a mathematical function. The equation governing the vibration of the pipe is derived according to Euler-Bernoulli beam theory.When the internal flow density varies with time,the pipe is excited parametrically.The stability of the pipe is determined by Floquet theory.Some simple parametric and combination resonances are determined.For a higher mass ratio(mean flow mass/pipe structural mass),higher flow velocity,or smaller end axial tension,the pipe becomes unstable more easily due to wider parametric resonance regions.In the subcritical flow velocity regime,the vibrations of the pipe are periodic and quasiperiodic for simple and combination resonances,respectively.However,in the supercritical regime,the vibrations of the pipe exhibit much richer dynamics including periodic,multiperiodic,quasiperiodic,and chaotic behaviors.

Keywords Pipe·Varying flow density·Parametric excitation·Stability·Nonlinear vibrations

1 Introduction

Pipes are widely used in many engineering structures and systems such as nuclear reactors, heat exchangers, marine risers,and submarine pipelines.They are usually applied as a fast and efficient means of transporting fluid flows such as water,oil,gas,and chemicals[1].A fluid-conveying pipe is a typical fluid-structure interaction system,which has been extensively studied for several decades both theoretically and experimentally,as reviewed by Païdoussis and Issid[2],Ibrahim[3,4],Pa¨ıdoussis[5],and Li et al.[6].

When the velocity of the internal fluid flow is sufficiently high,a simply supported pipe loses stability via a pitchfork bifurcation and starts to buckle while a cantilevered pipe loses stability via a Hopf bifurcation and starts to flutter[5].Such pipe vibrations in unstable regions have been widely simulated by many researchers using linear or nonlinear models in two or three dimensions[5-7].Moreover,some additional effects on pipes have also been considered and analyzed,including constrained springs,lumped masses,and external excitations[8,9].In these studies,the internal fluid flow is often considered as a single-phase flow, with both the flow velocity and density being constant and time independent.

However,the fluid flow is usually supplied by pumps,and its velocity may fluctuate in time due to their unsteady nature.In this circumstance,the pipe is parametrically excited by the internal varying flow velocity.This kind of parametric excitation has been investigated by many researchers.The stability of a pipe that parametrically excited by a fluctuating flow velocity was studied by Chang and Chen[10]using perturbation techniques and the averaging method.Some important effects on pipe stability were analyzed numerically by Jin and Song[11],who found that a pipe will become more unstable as the mean flow velocity is increased or the axial tension is decreased.The dynamics of a flexible pipe undergoing parametric excitation with internal resonance was investigated by Panda and Kar[12,13]using the multiple-scale method,revealing that multiple modes of the pipe will be excited by an internal pulsating flow velocity.The nonlinear vibrations of a pipe with a flow velocity fluctuating in the supercritical regime were predicted by Wang [14], who pointed out that such vibrations may be chaotic.Thereafter,Li and Yang[15]considered the influence of geometrical imperfections;their results presented that,as the amplitude of such imperfections increases, the vibrations of the pipe will become more severe.A curved pipe conveying a pulsating flow was simulated theoretically by Ni et al.[16]in three dimensions,revealing that the vibrations of a curved pipe are very complex.Recently,Łuczko and Czerwi´nski[17]adopted Floquet theory to study the stability of a clamped-clamped hose pipe conveying a pulsating flow; Their theoretical results were verified by experiment[18,19].

In practice,the fluid density inside a pipe may vary with both time and space, for example, when a pipe conveys a multiphase flow [20, 21]. In addition, when the fluid contains some solid particles, the total fluid density may also fluctuate both temporally and spatially. A horizontal pipe transporting a two-phase gas-liquid or three-phase gas-liquid-liquid flow was simulated theoretically by Bonizzi and Issa [22, 23], considering the entertainment between the different phase flows. A series of experiments was carried out by Monette and Pettigrew [24] to investigate a vertical cantilevered pipe transporting a two-phase gas-water flow,revealing that the stability and critical velocity of the pipe are significantly affected by the two-phase flow. The natural frequencies of a marine riser transporting oil,water,and gas were analyzed by Montoya-Hernández et al.[25].Their results demonstrated that the riser’s natural frequencies vary for different combinations of fluids. The Lagrangian slug tracking model was employed by Ortega et al. [26, 27] to simulate a slug flow traveling in a catenary riser, revealing that slug flow can cause severe fatigue damage to the riser.Recently,Chatjigeorgiou[28]investigated the dynamic response of a marine riser subjected to an internal steady slug flow. As the slugging frequency decreases, the internal fluid load and structural vibration displacement increase.Experiments were performed by Liu and Wang[29]to study a horizontal pipe transporting a two-phase gas-water flow,revealing that the fluid pressure will vary along the pipe.The fatigue damage to an ocean mining riser excited by external vortex-induced vibrations and internal slurry density variations was analyzed by Thorsen et al. [30]. Their results demonstrated that,when the wavenumber of the slurry density satisfies certain conditions,the vibrations of the riser will be strongly amplified.

For a fluid-conveying pipe, it is well known that, when the velocity of the fluid flow varies with time,the pipe will be parametrically excited. However, when the fluid density varies with time,the pipe will also be parametrically excited,although few researchers have paid attention to this kind of parametric excitation.The aim of this paper is thus to investigate theoretically a simply supported flexible pipe that is parametrically excited by an internal varying fluid density,focusing on the stability and nonlinear vibrations of the pipe.

This remainder of this manuscript is structured as follows:In Sect.2,a dynamical model for a flexible pipe conveying a

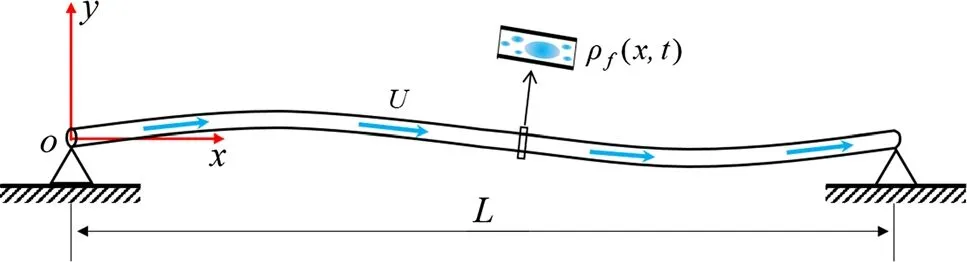

Fig.1 Simply supported pipe conveying variable-density flow

variable-density fluid is established and the solution methods are presented.In Sect.3,the stability of thepipeis determined by Floquet theory and some important effects on its stability are analyzed in detail.In Sect.4,the nonlinear vibrations of the pipe are simulated in the subcritical and supercritical flow regimes.Finally,the conclusions of the work are summarized in Sect.5.

2 Theoretical model and solution methods

2.1 Theoretical model

As shown in Fig.1,a horizontal pipe conveying a variabledensity fluid is considered. This pipe is long and flexible,and both ends are simply supported. A coordinate system o-xy is built at the left end, with the x-axis and y-axis in the horizontal and vertical direction,respectively.The pipe’s transverse displacement is expressed as y(x, t), where t is time.

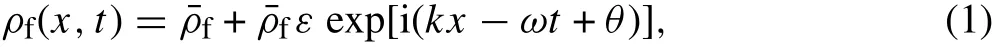

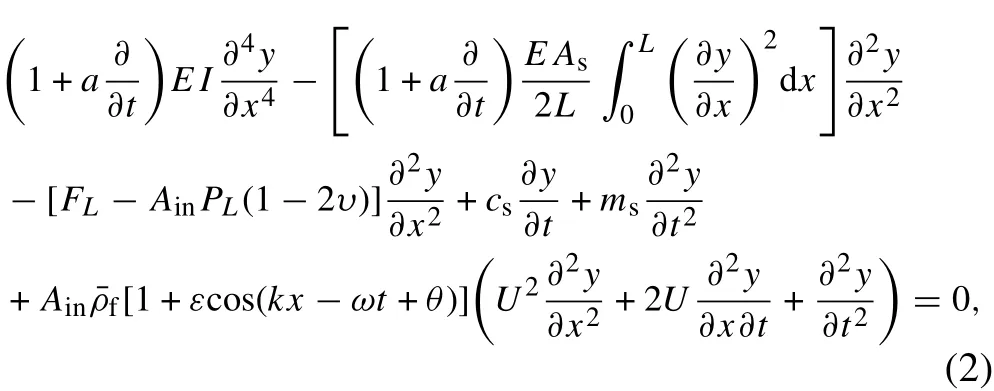

Two-phase flows,particularly gas-liquid flows,are widely encountered in pipes used in engineering applications[31-34]. When a two-phase gas-liquid flow travels inside a pipe,many kinds of flow patterns,e.g.,bubbly flow,stratified flow,wavy flow,plug flow,slug flow,froth flow,annular mist flow,and mist flow[35],as shown in Fig.2a,may occur.These flow patterns demonstrate that the total fluid density varies both along the pipe and in time.

To simulate the variation of the fluid density,the fluid flow is assumed to be incompressible.According to the studies of Patel and Seyed [20] and Bai et al. [21], the variable fluid density can be formulated as

Fig.2 a Flow patterns of two-phase gas-liquid flows[31]:(1)bubbly flow,(2)stratified flow,(3)wavy flow,(4)plug flow,(5)slug flow,(6)froth flow,(7)annular mist flow,and(8)mist flow;b variation of fluid flow density

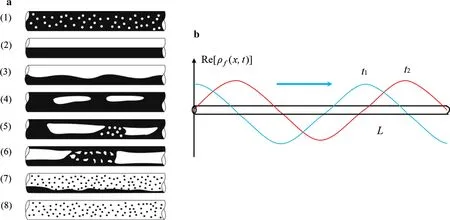

Since the pipe is long and flexible,rotary inertia and shear deformation can be neglected.Euler-Bernoulli beam theory is employed to describe the motion of the pipe. Based on Newton’s second law, Bai et al. [21] derived an equation for the vibration of a vertical cantilevered pipe conveying a variable-density fluid,using the density function in Eq.(1).Applying the same approach, an equation for the vibration of the present fluid-conveying pipe can be derived as

where the increase of the axial strain in the pipe structure is considered,the effect of gravity is neglected,and the real component of the fluid density function is mainly considered,with L being the length of the pipe,E the Young’s modulus,I the area moment of inertia,Asthe structural cross-sectional area of the pipe, Ainthe internal fluid cross-sectional area,msthe structural mass per unit length of the pipe,and a the coefficient of the Kelvin-Voigt-type viscoelastic damping.FLand PLare the axial tension and internal fluid pressure at x =L,respectively.υ is the Poisson’s ratio,and csis the coefficient of the viscous damping.

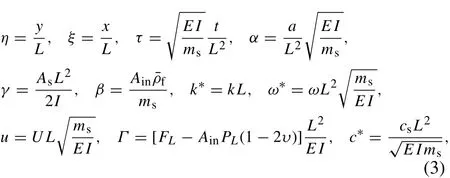

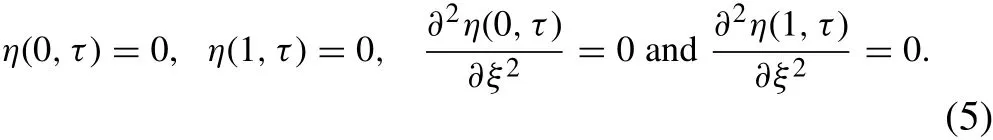

Introducing the following dimensionless variables and parameters:

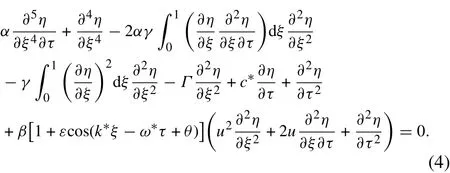

the equation for the vibration of the pipe can be expressed in dimensionless form as

The pipe is simply supported at both ends. The dimensionless boundary conditions are thus

The vibration Eq.(4)demonstrates that there are no external excitations on the pipe,but some of its coefficients change with time,indicating that the pipe is parametrically excited[36].The source of this parametric excitation is the internal varying fluid density.

2.2 Solution methods

To solve the equation for the vibration of such a pipe conveying a variable-density fluid, Galerkin’s method can be adopted.The dimensionless displacement of the pipe is thus approximated as

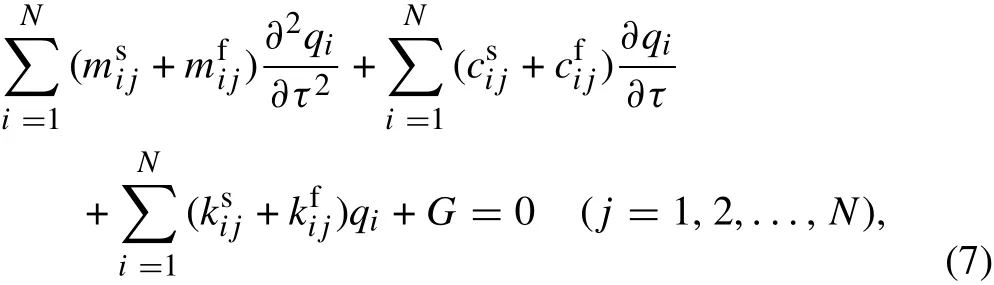

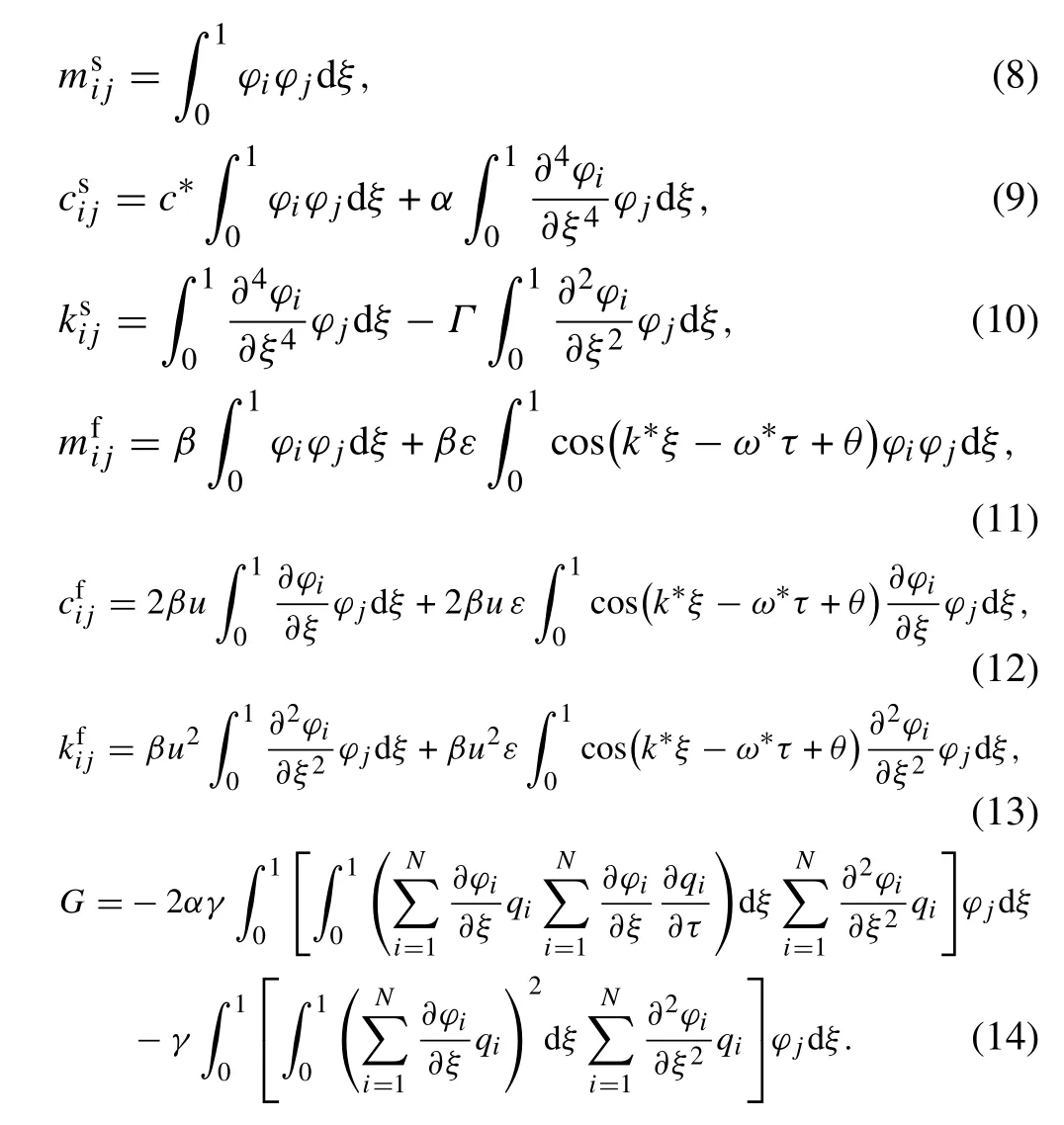

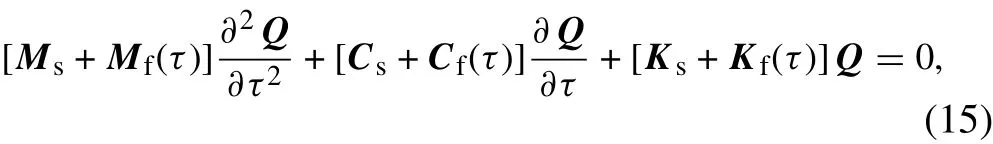

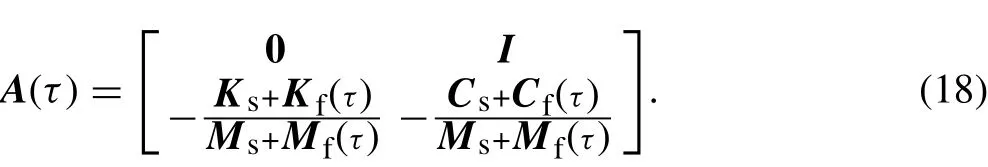

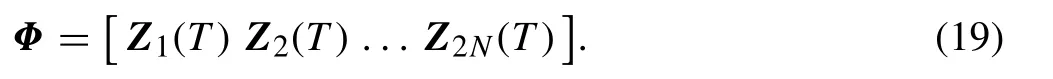

where φi(ξ) is the basis function, qi(τ) is the generalized coordinate,and N is the total number of basis functions.Since the pipe is simply supported,the basis function can be taken as φi(ξ) =sin(iπξ), which is the eigenfunction for a simply supported beam. Substituting Eq. (6) into Eq. (4),multiplying each term by φj(ξ)=(jπξ)(j=1,2,…,N),and integrating from ξ =0 to ξ =1 yields the equation

where

InEq.(7),the first three terms are the linear parts of the system,while the last term G contains the remaining,nonlinear parts.,andare respectively the mass,damping,and stiffness elements of the pipe structure and are thus time independent.Meanwhile,the elements,andcorrespond to the internal fluid flow and are therefore time dependent.The linear parts of the system can be expressed in matrix form as

with

with

The pipe is parametrically excited by an internal varying fluid density.Under certain conditions,the pipe will become unstable because of parametric resonances. To distinguish the parametric resonances, Floquet theory can be utilized.Equation (17) is thus integrated numerically over the time period τ = (0, 2π/ω*) for 2N times [36]; Each time, the initial conditions are set as [1, 0, 0,…]T, [0, 1, 0,…]T, …,and[0,…,0,1]T.The corresponding integral results Z1(T),Z2(T), …, and Z2N(T) are used to construct the following state transition matrix:

The eigenvalues λi(i=1,2,…,2N)of the state transition matrix Φ are then calculated. If at least one of these has absolute value greater than unity,i.e.,|λi|>1,then the system is unstable[5].

Moreover, when the pipe vibrates with large amplitude,the increase of the axial structural tension should also be considered, i.e., the nonlinear terms. The nonlinear vibrations of the pipe can then be simulated by solving Eq. (7)using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method.The initial calculation conditions are set as qi(0) = 0.001 and dqi(0)/dτ= 0 (i = 1, 2, …, N) [14, 15]. The first transient solutions are neglected,and the steady-state responses are mainly considered. The pipe’s vibration displacements and velocities are reconstructed using Eq.(6).The first ten basis functions are taken into account,i.e.,N =10.The calculation results are stable and convergent. The dynamic characteristics of the pipe can be further revealed with the help of bifurcation diagrams,phase-plane portraits,and Poincaré maps.

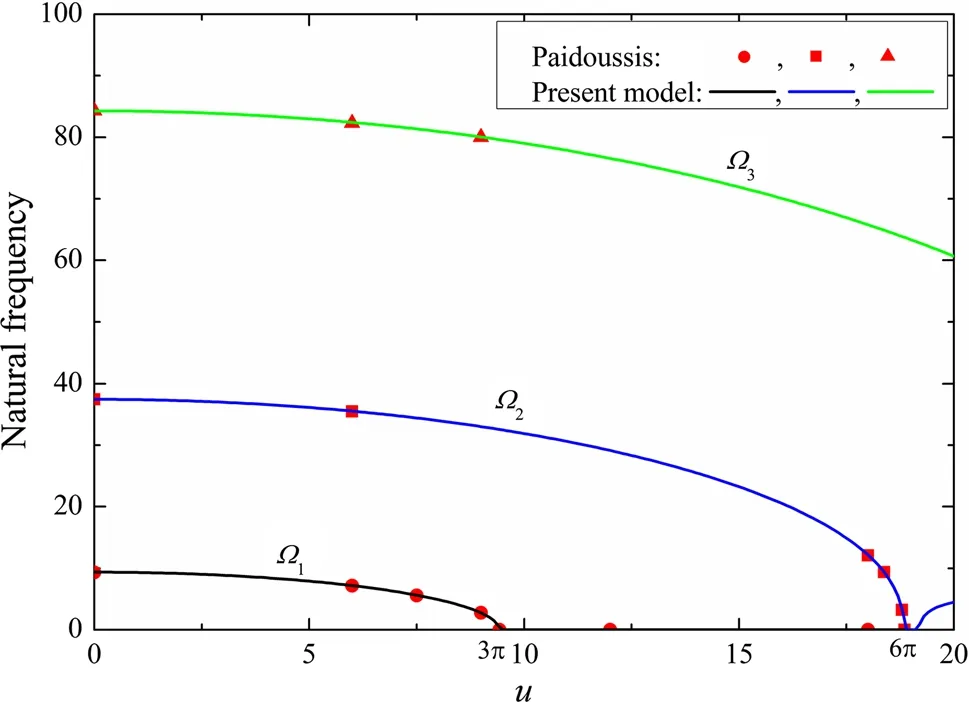

Fig.3 Natural frequencies of pipe with respect to flow velocity

3 Parametric instability

In this section,the parametric instability of the pipe is investigated.The dimensionless parameters are taken as β=0.11 and γ =Γ =c*=α=0,as given by Pa¨ıdoussis[5]and modified using the dimensionless variables presented in Eq.(3).Firstly,the natural frequencies of the fluid-conveying pipe are calculated by solving the standard eigenvalues of Eq. (17).The influence of the internal varying fluid density is neglected with ε=k*=ω*=0.The results obtained from the present model are compared with the results of Pa¨ıdoussis [5] in Fig. 3, in which the natural frequencies of the first three modes are plotted with respect to the flow velocity u. Note that the results of Pa¨ıdoussis [5] are modified in this figure using the dimensionless variables applied herein. Figure 3 shows that the results of the present model and those of Pa¨ıdoussis are in good agreement.

As the flow velocity u is increased,the natural frequencies of the pipe decrease.When the flow velocity u reaches 3π,the natural frequency of the first mode Ω1is reduced to zero,thus the pipe will start to buckle through a pitchfork bifurcation.Hence,ucr=3π is the critical flow velocity.

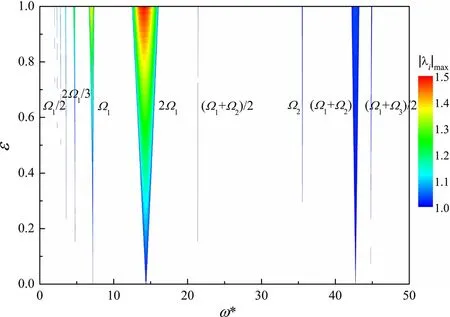

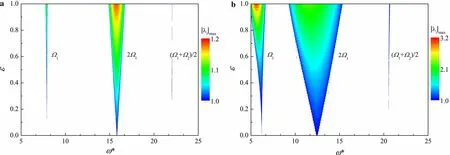

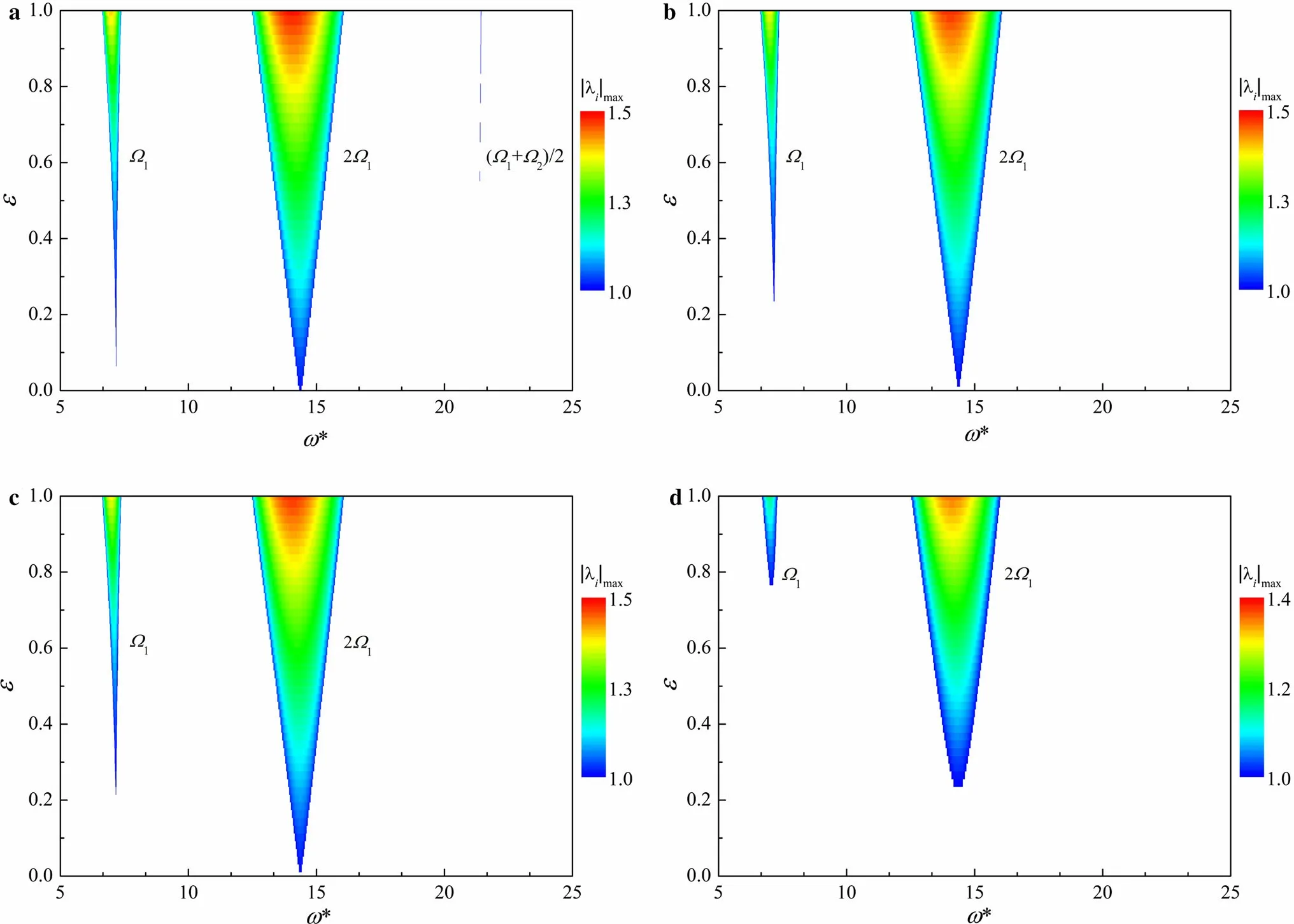

The parametric instability of the pipe should be analyzed in the subcritical regime of flow velocity,i.e.,u <ucr,because it will buckle in the supercritical regime (u >ucr). Hence,the flow velocity is chosen to be u = 6, which is less than ucr.The corresponding natural frequencies of the first three modes are Ω1=7.19,Ω2=35.55,and Ω3=82.41.Using Floquet theory, the stability and instability of the pipe are calculated and plotted in Fig. 4. In this figure, the circular frequency of the fluid density ω*increases from 0 to 50 in steps of 0.01.Meanwhile,the amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density ε increases from 0 to 1 in steps of 0.02.The influence of the phase angle θ is neglected, and its value is set to 0.

Fig.4 Stability of pipe parametrically excited by internal varying fluid flow density

The colored areas in Fig.4 show the unstable regions of the pipe,where the maximum eigenvalue of the state transition matrix exceeds unity, i.e., |λi|max>1. In contrast, the white areas show the stable regions where|λi|max≤1.As the circular frequency ω*is increased,some parametric resonances are excited by the internal varying fluid density.These resonances can be divided into simple parametric resonances and combination resonances.The simple parametric resonances consist of ω*= Ω1/2, 2Ω1/3, Ω1, 2Ω1, and Ω2, whereas the combination resonances including ω*= (Ω1+ Ω2)/2,(Ω1+Ω2),and(Ω1+Ω3)/2.

Comparison of Fig.4 with Fig.10,which shows the nonlinear vibrations of the pipe,reveals that,the larger the value of |λi|max, the greater the amplitude of the vibration of the pipe.This reflects that the pipewill be more seriously affected by the internal varying fluid density when the maximum eigenvalue of the state transition matrix is larger. In Fig. 4,it can also be seen that, as the amplitude of the fluctuation ε increases, the unstable regions broaden and the value of|λi|maxincreases. This means that the pipe becomes unstable more easily and will be more strongly affected by the fluid density when it varies with a larger amplitude. For the different parametric resonances,the unstable regions and maximum eigenvalues are different.The reason for this may be that the wavenumber of the fluid density k*is related to the circular frequency ω*through k*=ω*/u.With an increase of ω*, the wavenumber k*becomes larger while the wavelength(=2π/k*)decreases, thus the fluid density becomes more nonuniform, which will have some influence on the instability of the pipe.

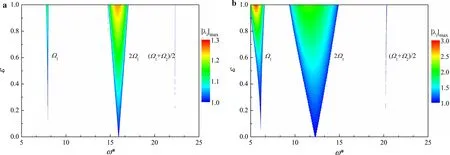

3.1 Effect of mass ratio β

The pipe may transport different types of fluids,so the mass ratio β (mean fluid mass/pipe structural mass)may vary.In order to analyze the effect on the stability of the pipe, the mass ratio is taken as β =0.08 and 0.15,respectively,while keeping the other parameters of the system constant.The stability of the pipe is calculated and plotted in Fig. 5, where the circular frequency ω*ranges from 5 to 25 to cover the parametric resonances ω*=Ω1,2Ω1,and(Ω1+Ω2)/2.In Fig.5,it can be seen that,as the mass ratio β increases,the unstable regions shift to the left.This is because the natural frequencies of the pipe decrease as the mass ratio is increased.When β=0.08,Ω1=7.97 and Ω2=36.60,whereas when β =0.15,Ω1=6.15 and Ω2=34.28.As the mass ratio is increased,the parametric resonances are excited by smaller circular frequencies of the fluid density.Figure 5 also shows that,with the increase of the mass ratio,the unstable regions broaden while the maximum eigenvalue |λi|maxincreases.This is reasonable because,for a larger mass ratio,the influence of the internal fluid flow on the pipe structure will be larger.It is thus seen that,with the increase of the mass ratio β, the pipe becomes more prone to instability and will be more seriously affected by the internal varying fluid density.

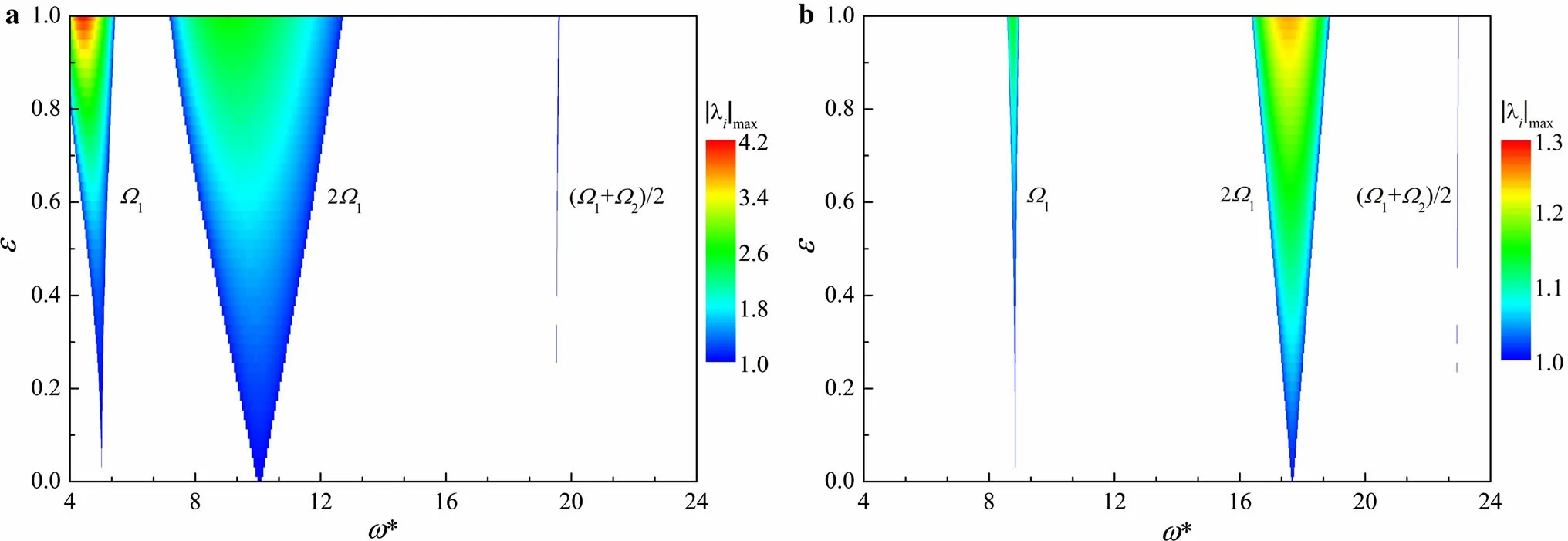

3.2 Effects of axial tension FL and internal fluid pressure PL

The pipe may be subjected to different end axial tensions or internal fluid pressures. Their effects on the stability of the pipe should thus be investigated. As shown in Eq. (3), the dimensionless parameter Γ depends on the axial tension FLand internal fluid pressure PL. When the axial tension FLis increased,the parameter Γ increases.Meanwhile,for the internal fluid pressure PL, the Poisson’s ratio υ should be considered. When υ >0.5, an increase in PLwill cause Γ to increase.In contrast,when υ <0.5,an increase of PLwill lead to a decrease in Γ.For υ =0.5,however,the influence of the internal fluid pressure can be neglected.

Figure 6 illustrates that, as the parameter Γ is increased from-3 to 3,the parametric resonances move to the right.This is caused by the natural frequencies of the pipe becoming larger, when Γ = -3, Ω1= 5.03, Ω2= 34.02, and when Γ = 3, Ω1= 8.84, Ω2= 37.01. For a larger Γ, the constraints on the pipe from the axial tension FLor internal fluid pressure PL(υ >0.5)are greater.As a result,the parametrically excited unstable regions become narrower and the associated maximum eigenvalues|λi|maxdecrease,as shown inFig.6.Therefore,the pipe will become more stable and less affected by the internal varying fluid density with increase of the axial tension or internal fluid pressure(υ >0.5).

3.3 Effect of flow velocity u

The velocity of the fluid flow transported by the pipe may vary.The effect of the flow velocity on the stability of the pipe is therefore shown in Fig.7 for u=5 and 7.As the flow velocity is increased,the natural frequencies of the pipe decrease,when u=5,Ω1=7.91,Ω2=36.14,and when u=7,Ω1=6.23,Ω2=34.83.Consequently,the parametric resonances are excited by smaller circular frequencies of the fluid density, as shown in Fig. 7. As the flow velocity is increased,the unstable regions widen while the maximum eigenvalues|λi|maxincrease. This is expected because, for higher flow velocity,the influence of the internal fluid flow on the pipe will be greater.As given in Eq.(4),the centrifugal force(βand the Coriolis force(βincrease with the flow velocity.It is thus seen that the pipe becomes more unstable and will be more strongly affected by the internal varying fluid density when the flow velocity is higher.

Fig.5 Effect of mass ratio β on pipe stability for a β =0.08 and b β =0.15

Fig.6 Effect of parameter Γ on pipe stability for a Γ =-3 and b Γ =3

Fig.7 Effect of flow velocity u on pipe stability for a u=5 and b u=7

3.4 Effects of viscous damping c*and viscoelastic damping α

The pipe material may differ and thus have different viscous and viscoelastic damping,which may cause some effects on the stability of the pipe.To analyze these effects,the dimensionless coefficient of the viscous damping is taken as c*=5×10-3and 5×10-2,and the dimensionless coefficient of the viscoelastic damping is taken as α = 5×10-4and 5×10-3.The stability of the pipe is plotted in Fig.8.It can be seen that, as these damping coefficients are increased, the parametric resonances do not shift to the left or right. This is reasonable because the natural frequencies of the pipe are not influenced by the damping. As these damping coefficients increase, the vibration energy of the pipe will decay faster with time.The unstable parametric regions thus shrink,especially for the case of ω*=(Ω1+Ω2)/2,disappearing in Fig.8b-d.Therefore,the pipe becomes more stable and will be less affected by the internal varying fluid density when the viscous or viscoelastic damping is increased.

4 Nonlinear vibrations

The pipe is parametrically excited by the internal varying fluid density. Its nonlinear vibrations should also be investigated. In this section, first the nonlinearity of the present model is validated,then the vibrations of the pipe are simulated in the subcritical and supercritical flow regime. The influence of the circular frequency and amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density are mainly considered and analyzed.

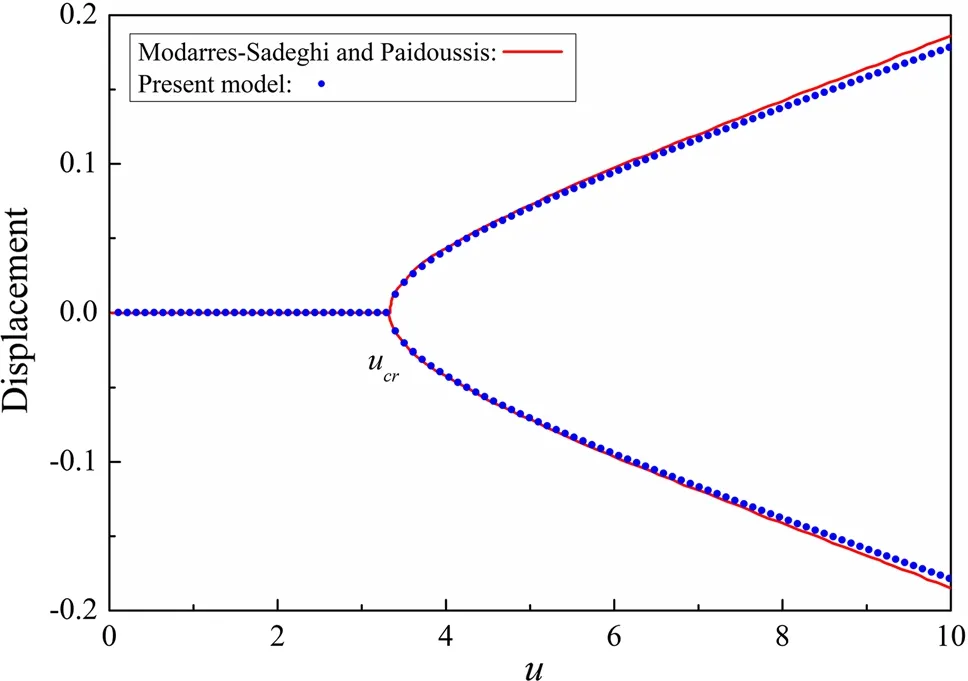

4.1 Validation of nonlinearity

In Sect.3,the linear parts of the present model are validated based on a comparison of the natural frequencies of the pipe.In this section,the nonlinear parts are validated,before analyzing the nonlinear vibrations of the pipe. The results of Modarres-Sadeghi and Pa¨ıdoussis[7]are taken for comparison.In their study,the internal fluid density was constant and the buckling amplitude of the pipe was plotted as a function of the flow velocity u, as shown in Fig. 9. The dimensionless parameters were taken as β = 0.887, γ = 500, and Γ= c*= 0. For this comparison, the variation of the fluid density is neglected (ε = 0). The viscoelastic damping is set as α =5×10-4to obtain the final static state.Figure 9 shows that the results from the present model and those of Modarres-Sadeghi and Pa¨ıdoussis[7]are in good agreement,although there are some discrepancies because gravity and the axial vibrations of the pipe are neglected in the present model.

Fig.8 Effects of viscous damping c* and viscoelastic damping α on pipe stability for a c* =5×10-3,b c* =5×10-2,c α=5×10-4,and d α=5×10-3

Fig.9 Buckling amplitude of pipe with respect to flow velocity

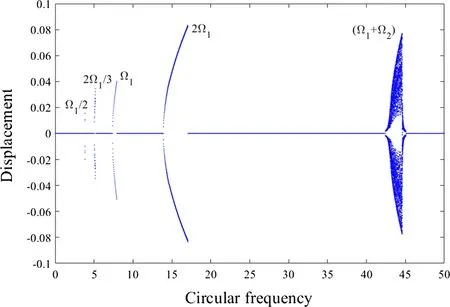

Fig.10 Bifurcation diagram of pipe with respect to circular frequency of flow density ω* in subcritical regime

As shown in Fig.9,the pipe is stable when the flow velocity u is less than the critical velocity ucr. However, beyond the critical velocity ucr,the pipe buckles.There are two buckling shapes (negative and positive) of the pipe, which are around the original state.The buckling amplitude increases with increase of the flow velocity u.

4.2 Vibrations in subcritical regime

Since the behavior of the fluid-conveying pipe exhibits different features in the subcritical (u <ucr) and supercritical(u >ucr) flow regimes, the vibrations of the pipe parametrically excited by the internal varying fluid density should be analyzed in these regimes separately.The dimensionless parameters are taken as β =0.11,γ =50,Γ =1,c*=5×10-3,and α =5×10-4,in accordance with the analysis in Sect.3.The critical flow velocity is ucr=9.98.

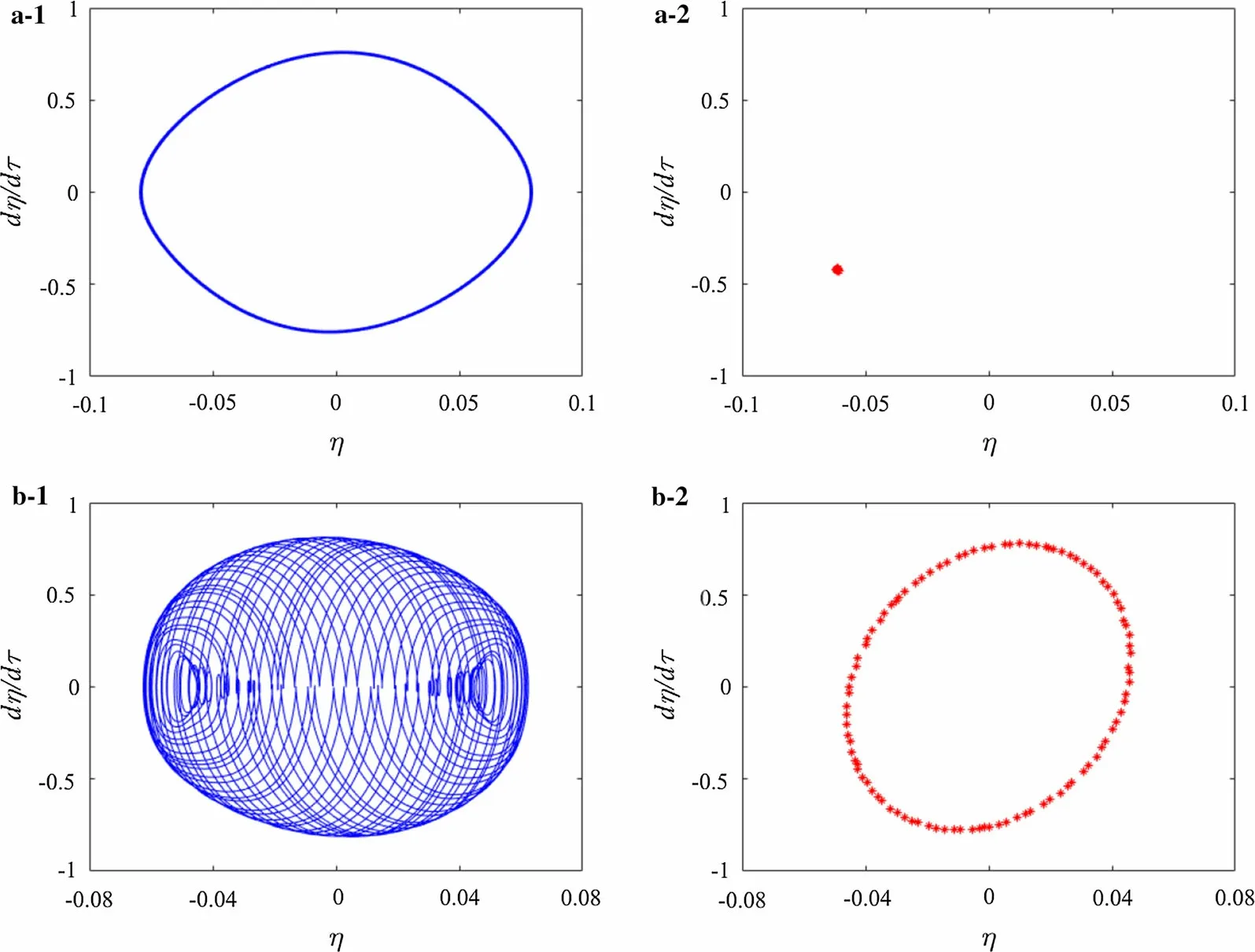

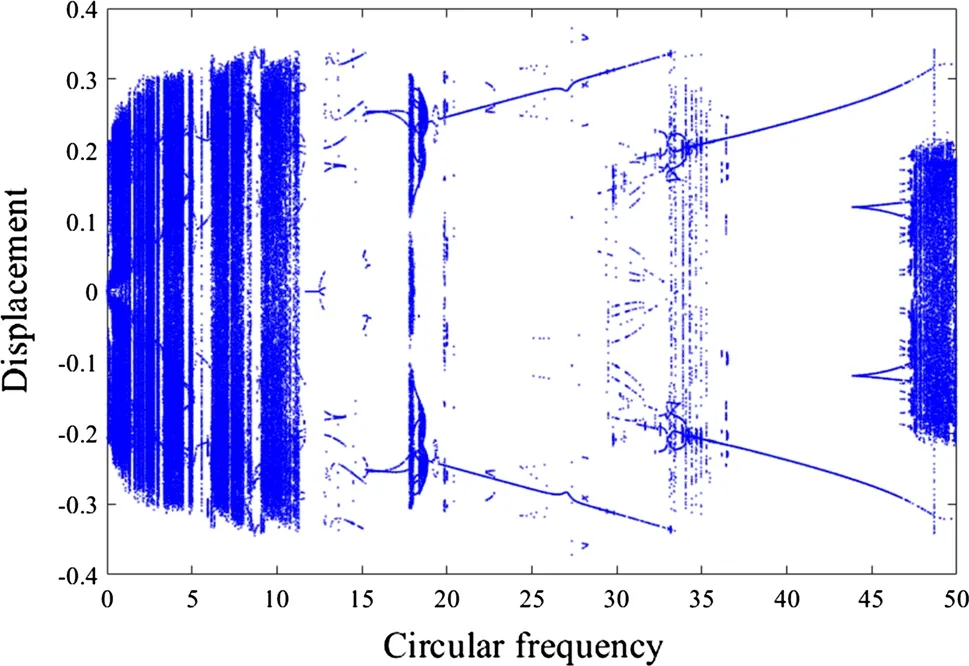

For the vibrations in the subcritical regime, the flow velocity can be selected as u = 6. In this case, the natural frequencies of the first two modes are Ω1=7.78 and Ω2=36.04.The nonlinear vibrations of the pipe are calculated for a circular frequency of the fluid density ω*increasing from 0 to 50.The fluctuation amplitude and phase angle of the fluid density are set as 1 and 0, respectively. The vibration displacement of the pipe at ξ=0.25 is recorded when its velocity is zero.Then,a bifurcation diagram is constructed as plotted in Fig.10.This figure shows that the vibration amplitude of the pipe increases at the parametric resonances of ω*=Ω1/2,2Ω1/3,Ω1,2Ω1,and(Ω1+Ω2).Out of these resonances,the vibration displacements are very small.Since the parameter Γ,increases of the structural tension,viscous damping,and viscoelastic damping are considered, the unstable regions in Fig. 10 are less than those in Fig. 4. Furthermore, the vibrations of the pipe are periodic at the simple parametric resonances of ω*=Ω1/2,2Ω1/3,Ω1,and 2Ω1,as typically depicted in Fig.11a for the case of ω*=2Ω1.This is because only one mode of the pipe is excited by the internal varying fluid density.On the other hand,at the combination resonance of ω*=(Ω1+Ω2),the vibrations of the pipe are quasiperiodic,as shown in Fig.11b.This is because two modes of the pipe are excited and participate in the vibrations.

Fig.11 Phase-plane portraits(1)and Poincaré maps(2)of vibrations of pipe at a ω* =2Ω1 with periodic motion and b ω* =(Ω1 +Ω2)with quasiperiodic motion

Fig.12 Bifurcation diagrams of pipe with respect to amplitude of fluctuation of flow density ε in subcritical regime at a ω*=2Ω1 and b ω*=Ω1+Ω2

Fig.13 Bifurcation diagram of pipe with respect to circular frequency of flow density ω* in supercritical regime

To show the dependence of the nonlinear vibrations of the pipe on the amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density,bifurcation diagrams are plotted in Fig. 12 for the range of 0≤ε ≤1.The parametric resonances of ω*=2Ω1and ω*=(Ω1+Ω2)are representatively considered.In Fig.12,it can be seen that,once the parametric resonances are excited,the vibration displacement of the pipe jumps to large values.After this,the displacements increase steadily with increasing fluctuation amplitude ε. The vibrations of the pipe are always periodic for ω*= 2Ω1and quasiperiodic for ω*=(Ω1+ Ω2). This means that the dynamics of the pipe are seldom affected by the amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density.

4.3 Vibrations in supercritical regime

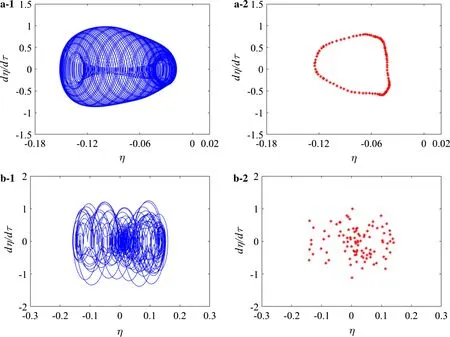

For the vibrations of the pipe in the supercritical regime,the flow velocity can be selected as u = 12. When the internal fluid density varies with time,the nonlinear vibrations of the pipe are calculated, and a bifurcation diagram is plotted in Fig.13 for a different circular frequency of the fluid density.The corresponding phase-plane portraits and Poincaré maps are plotted in Fig.14.

In Fig.13,it can be seen that the dynamics of the pipe in the supercritical regime becomes more complex when compared with Fig.10 in the subcritical regime.This is because the pipe is unstable at the original state and has two stable symmetrical buckling states.In the range of 0≤ω*≤11.29,Fig.13 shows that the vibrations of the pipe are chaotic;For instance,when ω*=3 and ω*=10,chaotic vibrations are demonstrated in Fig.14a and c,respectively.These chaotic vibrations appear as the pipe vibrates around the negative and positive buckling states. Some periodic vibrations are also embedded in this range.As an example,when ω*=5.20,Fig.14b shows that the vibration of the pipe is period-2. In Fig. 14b-1, it can be found that this periodic vibration is asymmetric. When 11.30≤ω*≤17.81, the vibrations of the pipe are periodic including period-1 and period-2.In the range of 17.82≤ω*≤19.11,the vibrations of th pipe are chaotic then evolve into multiperiodic, quasiperiodic (Fig.14d), and periodic. After this, there is a wide range (19.53≤ω*≤43.87) in which the vibrations are periodic.Within this range,some chaotic vibrations are still embedded,especially when ω*is around 34. in the range of 43.88≤ω*≤50, the vibrations of the pipe evolve from period-1 to multiperiodic(Fig.14e)then to chaotic.

To show the effect of the amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density on the vibrations of the pipe, bifurcation diagrams are plotted in Fig.15.Circular frequencies of the fluid density of ω*=10 and ω*=40 are typically considered.It can be seen that, as the amplitude of the fluctuation ε is increased, the dynamics of the pipe changes dramatically,in contrast to Fig.12.This means that the vibrations of the pipe would be significantly affected by the amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density.

Fig.16 Phase-plane portraits(1)and Poincaré maps(2)of vibrations of pipe at ω* =40:a ε=0.192 with quasiperiodic motion and b ε=0.222 with chaotic motion

In the case of ω*= 10, when the amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density is small(0<ε ≤0.105),Fig.15a shows that the vibrations of the pipe are periodic. These vibrations are around the positive or negative buckling state.In the range of 0.106≤ε ≤0.374,the vibrations of the pipe change from chaotic to periodic then back to chaotic.After this range,there is a wide range(0.375≤ε ≤0.764)in which the vibrations of the pipe are multiperiodic.In the range of 0.765≤ε≤1.0, the vibrations of the pipe alternate between periodic and chaotic.

For the case of ω*= 40, Fig. 15b presents the different changing trends observed for the vibrations of the pipe.When 0<ε ≤0.049,the vibrations of the pipe are very small and are around the negative buckling shape.In the range of 0.050≤ε ≤0.201, the vibrations of the pipe are quasiperiodic,as demonstrated in Fig.16a for ε=0.192.In the range of 0.202≤ε ≤0.450,the vibrations of the pipe are chaotic,as typically shown in Fig.16b for ε =0.222.In this range,some periodic and quasiperiodic vibrations are also embedded.When 0.451≤ε ≤1.0,the vibrations of the pipe evolve from multiperiodic to chaotic then to periodic. There is a wide range in which the vibrations of the pipe are period-1.

5 Conclusions

Pipes are widely used in engineering applications to transport fluid flows. When they contain multiphase flows, the total fluid density may vary in both time and space.In this paper,a simply supported pipe conveying a variable-density fluid is investigated theoretically.The variation of the fluid density is simulated using a mathematical function.An equation for the vibration of the pipe is developed using Euler-Bernoulli beam theory.When the internal fluid density varies with time,the pipe is parametrically excited.The parametric instability is determined by Floquet theory.The nonlinear vibrations are simulated using numerical methods.The conclusions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

1. As the circular frequency of the fluid density is increased,some simple parametric and combination resonances of the pipe are excited. At these resonances, the pipe becomes unstable.As the amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density is increased,the pipe becomes unstable more easily and will be more seriously affected by the internal fluid density.

2. When the mass ratio or flow velocity is increased, the influence of the internal fluid flow on the pipe becomes stronger.As a result,a pipe excited by an internal varying fluid density will become more unstable over broader regions.In contrast,when the end axial tension or internal fluid pressure(υ >0.5)is increased,the pipe becomes more constrained and more stable,with narrower unstable regions. When the viscous or viscoelastic damping is increased, the unstable regions shrink and the pipe becomes more stable.

3. In the subcritical regime, the vibrations of the pipe are periodic for the simple parametric resonances and quasiperiodic for the combination resonances. The dynamics of the pipe are seldom affected by the amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density.

4. In the supercritical regime, the vibrations of the pipe exhibit much richer dynamics,including periodic,multiperiodic, quasiperiodic, and chaotic behaviors. The dynamics of the pipe is largely affected by the amplitude of the fluctuation of the fluid density.

A theoretical study on a flexible pipe transporting a variable-density fluid is presented herein. In the future,experiments should be performed to obtain better understanding of such pipes conveying multiphase flows.

AcknowledgementsThe authors are grateful to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 51679167, 51979193, and 51608059)for financial support.

杂志排行

Acta Mechanica Sinica的其它文章

- Geometric and material nonlinearities of sandwich beams under static loads

- Coupled thermoelastic theory and associated variational principles based on decomposition of internal energy

- Transient growth in turbulent particle-laden channel flow

- Experimental and theoretical investigation of the failure behavior of a reinforced concrete target under high-energy penetration

- Revealing the high-frequency attenuation mechanism of polyurea-matrix composites

- Efficient algorithm for 3D bimodulus structures