Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: The impact of evolving experience and new technologies in diagnosis and treatment over the last two decades

2020-03-03PitroGmittAnnMffioliJnSpiropoulosAntonioArmllinoMurizioVrtmtiPoloAsni

Pitro Gmitt , , Ann Mffioli , Jn Spiropoulos , Antonio Armllino , Murizio Vrtmti , Polo Asni , f,*

a Endoscopy Unit, ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Milan, Italy

b Endoscopy Unit, ASST Fatebenefratelli Sacco, Milan, Italy

c Chirurgia Generale 1, ASST Fatebenefratelli Sacco, Milan, Italy

d Endoscopy Division, Ospedale San Leopoldo Mandic di Merate, ASST Lecco, Lecco, Italy

e Dipartimento di Scienze Biomediche e Cliniche “L. Sacco”, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy

f Department of Emergency Medicine, ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Milan, Italy

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound Acute necrotizing pancreatitis Pancreatic fluid collections Pancreatic pseudocyst

ABSTRACT Background: Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage is the preferred approach for drainage of pan- creatic fluid collections (PFCs) due to the better experience and significant progress using newer stents and access devices during last decade. This study aimed to evaluate the role of the evolving experience and possible influence of new technological devices on the outcome of patients evaluated for PFCs and submitted to EUS-guided drainage during two different periods: the early period at the beginning of ex- perience when a standardized technique was used and the late period when the increased experience of the operator, combined with different stents quality were introduced in the management of PFCs. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of a cohort of 91 consecutive patients, who un- derwent EUS-guided drainage of symptomatic PFCs from October 2001 to September 2017. Demographic, therapeutic results, complications, and outcomes were compared between early years’ group (20 01-20 08) and late years’ group (2009-2017). Results: Endoscopic treatment was successfully achieved in 55.6% (20/36) of patients in the early years’ group, and in 96.4% (53/55) in the late years’ group. Eighteen patients (12 in early years’ and 6 in the late year’s group) required additional open surgery. Procedural complications were observed in 5 patients, 4 in early years’ and 1 in late years’ group. Mortality was registered in two patients (2.2%), one for each group. Conclusions: During our long-term survey using EUS-guided endoscopic drainage of PFCs, significantly better outcomes in term of improved success rate and decrease complications rate were observed during the late period.

Introduction

Pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) are com- mon complications of severe acute pancreatitis and, less frequently, chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic trauma. Drainage of these PFCs may be necessary for symptomatic patients complaining of abdom- inal pain, gastric outlet, biliary obstruction, or infection.

The traditional mainstay of treatment for severe pancreatic necrosis and abscess before the last decades was surgery [1-3] . However, surgical treatment was associated with high morbidity (13 % -53%), and mortality (6.2 % -25%) and repeated laparotomies were frequently required (17 % -72%) for the residual necrotic process [4-6] . For these reasons, endoscopic drainage of PFCs has been increasingly utilized and developed during the last 20 years. Transenteric drainage with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)- guidance is now regarded as the technique of choice due to significantly higher rates of technical success than conventional endoscopic drainage (95% vs. 60%) [7,8] and is associated with lower morbidity when compared to surgery and percutaneous methods [9,10] . The development of EUS has expanded the safety and efficacy of this modality into two steps: (i) during the di- agnostic phase: improving distinction between partially liquified necrotic collections and true pseudocysts, which can be difficult by computed tomography (CT), and differentiating inflammatory collections from pancreatic or peripancreatic cystic neoplasia; (ii) during the therapeutic phase: allowing endoscopists to drain non- bulging and high-risk fluid collections by visualizing any important interposed vessels between the gastrointestinal tract and the cystic wall [11,12] .

Significant changes to the nomenclature of PFCs have been re- cently adopted, and in 2012 an International Consensus [13] sim- plified the 1992 Atlanta Classification of PFCs [14] and reclassified pancreatic and peripancreatic collections into four groups, accord- ing to the presence of necrotic or non-necrotic collection and the time from the onset of symptoms ( < 4 or > 4 weeks): (i) acute pan- creatic fluid collections (APFC) and acute necrotic collection (ANC) in the early phase, before 4 weeks and without a defined wall; (ii) pancreatic pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis, contained within a thickened wall, presenting after 4 weeks from the onset of pancre- atitis.

This retrospective study aimed to review over a period of 16 years the evolving experience, new technologies, and the possi- ble different outcome of two groups of patients with PFCs submit- ted to EUS-guided drainage during two different periods of time: the early years’ group from 20 01-20 08 when a standardized tech- nique at the beginning of the experience was employed; and the late years’ group from 2009-2017, when the increased experience, the introduction of the new self-expandable metal stents (SEMS), the practice of stenting of the pancreatic duct abnormalities, and the new Atlanta classification were introduced in the clinical practice.

Methods

Patients with PFCs referred to the Endoscopic Unit for EUS eval- uation between October 2001 and September 2017 were identi- fied from a dedicated database. The retrospective chart review and analysis of data have been approved by the local institutional re- view board and ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

PFCs were initially characterized by CT, enhanced with intra- venously and orally administered contrast, or MRI, to identify the number, size, and location of each collection. The indications for drainage of PFCs were as follows: recurrent abdominal pain, gas- tric outlet or biliary obstruction, rapidly enlarging PFCs and in- fected PFCs with clinical evidence of systemic inflammatory re- sponse syndrome or sepsis. Diagnostic EUS was performed in all patients before drainage, and the indications were discussed by a multidisciplinary team composed by a senior resident of the oper- ative endoscopic Unit, gastroenterologist, and surgeon. A definitive consensus about the correct therapeutic strategy was always es- tablished according to recognized inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients were considered eligible for transmural drainage if the col- lection met the following criteria: (i) when they present with pan- creatic pseudocysts or walled-off necrosis (according to the origi- nal Atlanta classification and after 2012 to revised Atlanta classifi- cation), (ii) when PFCs were in proximity ( < 1 cm) to the duodenal or gastric wall and endoscopically accessible, (iii) when PFCs were presenting after 4 weeks from the onset of pancreatitis. Patients with an acute fluid collection, asymptomatic pancreatic pseudo- cysts, necrotic collection with only minimal liquefaction, suspected mucinous cystic neoplasm or PFCs not in proximity of EUS probe were all excluded from the endoscopic treatment.

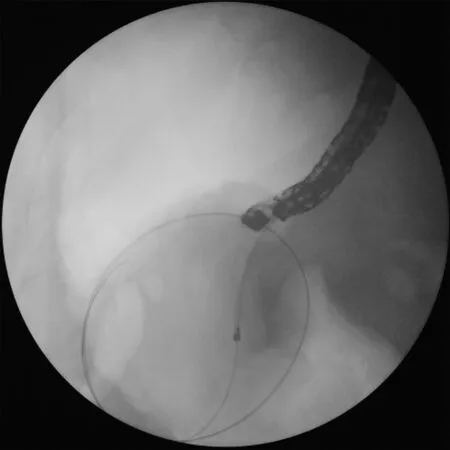

Fig. 2. A 6-French cystotome inserted over the guidewire into the cyst using elet- trocautery to avoid bleeding.

Standard technique during the early years (20 01-20 08)

The patients underwent the procedure under general anesthe- sia or conscious sedation; broad-spectrum antibiotics were admin- istered during and after the procedure. PFCs drainage was per- formed using a linear array echoendoscope with a 3.8 mm working channel (Pentax, Pentax Medical, Tokyo, Japan). A 19-Gauge nee- dle (Wilson-Cook, Cook Medical, Bloomington, USA) was used to perform the initial puncture of the collection under EUS guidance ( Fig. 1 ); an aliquot of the cystic content was obtained for micro- biological and cytological investigation as well as laboratory anal- ysis for amylase and carcinoembryonic antigen. A 0.035-inch stiff guidewire was inserted through the needle under fluoroscopy and was coiled into the cyst; the needle was then removed, and a nee- dle knife or a 6-French cystotome was inserted over the guidewire into the cyst using electrocautery to avoid bleeding ( Fig. 2 ). The needle knife was exchanged over the guidewire for a dilation bal- loon, and the tract was dilated up to 12-20 mm ( Fig. 3 ). In patients with pancreatic pseudocyst, one or two 7-10 French double-pigtail endoprostheses were placed in the cyst, and an additional naso- cystic tube was placed in case of infection, and continuous lavage was utilized through the naso-cystic tube with normal saline for 48-72 h, and then removed.

Fig. 3. Dilation balloon over guidewire to dilate the tract up to 12 mm.

Fig. 4. Transgastric fully-covered self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) placed in the necrotic cavity.

Standard technique during late years (2009-2017)

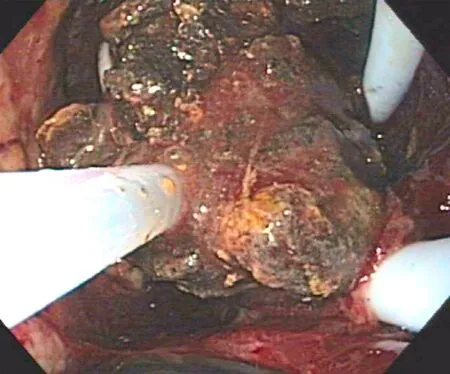

In patients with walled-off necrosis, the transluminal access was dilated up to 12 mm, and a fully-covered SEMS (Niti-S Nagi Stent 16 mm in diameter and 30 mm in length) was placed ( Fig. 4 ). Endoscopic debridement with a loop or a Dormia basket was per- formed every 2-3 days ( Fig. 5 ), until most of the necrotic mate- rial was removed and granulation tissue was identifiable on the wall of the cavity. Only patients with necrotic debris more than 30% were considered for necrosectomy; 12 patients with minimal necrosis ( < 30%) or puruloid material were submitted to transmural plastic stent and catheter as definitive treatment without necro- sectomy and were classified as infected pancreatic pseudocysts. Patients with extensive debris of more than 40 % -50% usually re- quired several treatments.

Fig. 5. Endoscopic debridement (necrosectomy) with a Dormia basket into the cyst cavity.

Finally, 2 or 3 double-pigtail endoprostheses (7-10 French) were left in place. We used metal stents for drainage of the necrotic col- lection in order to facilitate the passage of a gastroscope into the retroperitoneum and to perform endoscopic necrosectomy. Plastic stents were used for drainage of fluid collections in patients with pseudocysts.

In the case of collection due to biliary pancreatitis, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy was performed during the first session. ERCP and pancreatic stent- ing for the treatment of pancreatic duct abnormalities were per- formed in all cases of recurrent PFCs. We determined pancreatic duct abnormalities first of all by MRCP and subsequently by ERCP, which was also employed for their treatment.

Immediate adverse events and the resulting treatments re- quired during the procedure were carefully documented and recorded.

Follow-up and stent management

All patients drained by plastic stents were evaluated with contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen three months after the pro- cedure in an outpatient setting, and the endoprostheses were re- moved if there were no complications or lesion recurrence during the post-interventional course. In patients with SEMS, the endo- prostheses were removed within 3-4 weeks to avoid inflamma- tory tissue ingrowth and stent migration. Patients were followed up during the study period at regular intervals of 4-6 months and repeat imaging by CT, MRCP, and EUS were only performed in case of clinical suspicion of PFC recurrence.

Outcome measures

The primary end-point of this study was to determine the tech- nical and clinical successes of the EUS-guided PFCs drainage in the two groups of patients (early years’ group and late years’ group). The therapeutic success was defined as the complete resolution of the collection and related symptoms, as demonstrated by clin- ical and radiological follow-up without the need for surgical in- tervention. Secondary outcomes included mortality rate, the need of endoscopic reintervention or percutaneous drainage by inter- ventional radiology and the incidence of procedural-related ad- verse events (bleeding, perforation, stent migration, and free air in the abdomen). All recorded primary and secondary outcomes were compared between the two groups.

Table 1 Patient demographic and PFCs characteristics.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were computed by using STATA 14.0 soft- ware (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). Quantitative vari- ables were expressed as median (interquartile range), and quali- tative data as percentage. Statistical analyses for comparing out- comes of the two groups were performed using the Pearson Chi- square test for categorical data. Differences were considered statis- tically significant with a two-sided P value < 0.05.

Results

Patient demographic and PFCs characteristics

From October 2001 to September 2017, 138 consecutive pa- tients with a diagnosis of PFCs were referred to the Endoscopic Unit for EUS evaluation: 47 patients were excluded from EUS- guided drainage, due to the presence of APFC ( n = 13), asymp- tomatic pancreatic pseudocyst ( n = 21), tissue necrosis with only minimal liquefaction ( n = 4), or endoscopic features suggesting the diagnosis of mucinous cystic neoplasm during the EUS diagnostic phase ( n = 9). Ninety-one patients underwent EUS-guided transmu- ral drainage of PFCs and 73.6% were men. Of the 91 patients with PFCs evaluated, 69 presented with pancreatic pseudocyst; the re- maining 22 patients presented with walled-off necrosis. The me- dian age of patients was 58 years for patients with pancreatic pseudocyst and 60 years for patients with walled-off necrosis. Me- dian long axis diameter of PFCs was 81 mm for pancreatic pseu- docyst and 129 mm for walled-off necrosis. Time from acute pan- creatitis to drainage of PFCs was 119 days for pancreatic pseudo- cyst and 45 days for walled-off necrosis. The leading causes of pancreatitis were alcohol (33.0%), gallstones (31.9%) and idiopathic (18.7%); other causes of pancreatitis in 16.5% included pancreas di- visum, post-ERCP, and autoimmune pancreatitis. The majority of PFCs (45.1%) was located in the body, followed by the tail (29.7%) and head (25.3%) of the pancreas; two patients (2.2%) had multiple pseudocysts, one complicated by gastric varices ( Table 1 ).

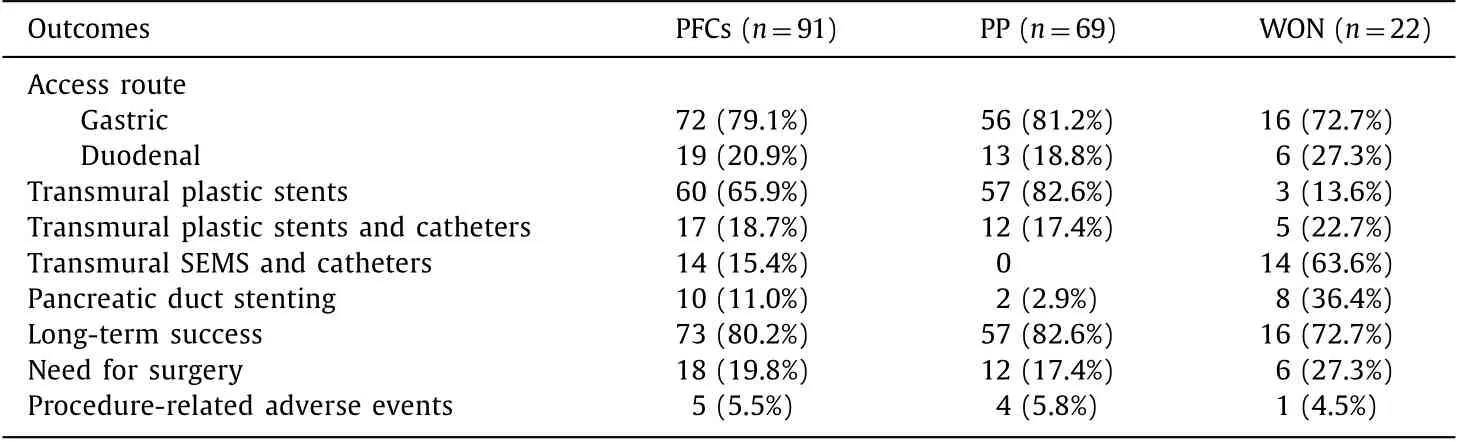

Endotherapy results

Seventy-two patients received transgastric drainage (79.1%) and 19 transduodenal (20.9%). Of the 69 patients with pancreatic pseu- docyst, 57 (82.6%) underwent EUS-guided transmural plastic stents placement, while 12 (17.4%) with infective pseudocysts had addi- tional naso-cystic tube placement. Of the 22 patients with walled- off necrosis, 3 (13.6%) underwent transmural plastic stents place- ment, 5 (22.7%) had additional naso-cystic tube placement and 14 (63.6%) underwent SEMS and naso-cystic tube placement. Ten pa- tients (2 with pancreatic pseudocysts and 8 with walled-off necro- sis) were submitted to ERCP with pancreatic stent placement for the treatment of recurrent PFCs due to pancreatic duct leakage ( Table 2 ). In patients with walled-off necrosis, we observed 4 with complete disconnected duct and these were treated by permanent plastic stent into the Wirsung until the disruption orifice. Our pro- tocol in these cases was stent replacement at a one-year interval. In the other patients, with leak from partial disruption of the pan- creatic duct it was possible to stent the entire pancreatic duct until the tail (in 4 patients from the minor papilla).

Outcomes

The long-term overall success rate in patients with pancre- atic pseudocysts was achieved in 57 patients (82.6%). Twelve patients (17.4%) with endoscopic treatment failure required sur- gical treatment. The long-term success rate in patients with walled-off necrosis was achieved in 16 patients (72.7%). Immedi- ate procedure-related adverse events occurred in 4 patients in the early period: 2 pseudocyst perforation (one treated conservatively), 1 massive gastric bleeding and 1 stent migration into the cyst which required surgical treatment. Two patients died of sepsis at day 28 and 16 after the procedure, one in each period.

Comparison of endotherapy and outcomes between the early and late period

Different technical procedures were compared as well as the outcomes in the early and late years’ group ( Table 3 ). In the early years’ group 36 patients underwent endoscopic treatment, and the long-term success rate was 55.6% with 11.1% of procedure-related adverse events. In the late years’ group, 55 patients were treated, with a 96.4% success rate and 1.8% of adverse events and the dif- ference was statistically significant of procedure-related adverse events between ( P = 0.049 and P = 0.040).

Discussion

With the development of technical innovations, invasive surgi- cal procedures have been replaced for the majority of patients with PFCs by interventional endoscopy over the last two decades. Acute collections (APFC and ANC) usually do not require any interven- tion for drainage as the majority of patients improves with con- servative management. However, a substantial proportion of symp- tomatic patients with walled-off necrosis and pancreatic pseudo- cyst will require EUS-guided drainage.

In our experience among 138 patients referred to the Endo- scopic Unit for PFCs evaluation, 91 (65.9%) fulfilled our inclu- sion criteria and underwent to EUS-guided drainage; this data seems in accord with other clinical reports where about 40% of acute pseudocysts resolved spontaneously within 6 weeks after discovery [15,16] . Also in our experience, diagnostic EUS allowed to exclude one third (34.1%) of patients from unnecessary drainage, detecting cystic neoplasia, necrosis without liquid content, or PFCs in the absence of defined wall around the collection.

Our study has some limitations since it covers a long period of time of sixteen years, and is monocentric and retrospective in nature. However, there is general agreement to support the hy- pothesis that during the last decade the new technical devices and new strategies might have substantially improved the efficacy and safety of endoscopic drainage of PFCs [17,18] . Although the num- ber of patients with walled-off necrosis treated by EUS increased from 5.6% patients during the early years to 36.4%, the long-term of success rate during the late period was considerably evident.

Table 2 Endotherapy results and outcomes.

Table 3 Comparison of endotherapy and outcomes between early and late period.

In the late years’ group, a reduced incidence of adverse clinical events (from 11.1% to 1.8%) and a decreased need for surgery from 33.3% to 10.9% were also observed. It is reasonable to suppose that other factors than new technical devices may have contributed to the better outcome in the late period such as the evolving experi- ence and technical skills as a consequence of the learning curve.

Patients with necrotic collections during the early period, were mainly addressed to surgical evaluation, whereas in the late pe- riod they were primarily evaluated for endoscopic treatment: this can explain a predominant incidence of pancreatic pseudocyst over walled-off necrosis during the early period.

During the last decade, some advances in cross-sectional body imaging, and additionally EUS, have also enabled a clear distinction and recognition of PFCs, allowing a correct triage of patients to re- ceive the appropriate endoscopic treatment with the exclusion of a consistent number of patients from unnecessary procedures.

The treatment of pancreatic necrosis is more complex than pseudocysts, and inadvertent transluminal drainage of a walled-off necrosis using conventional endoscopic cystogastrostomy predis- poses the patient to infection with adverse clinical outcome [19] . The novel-lumen apposing SEMS, developed in the last decade, minimizes the possibility of leak or perforation and the wider stent lumen enables better drainage of the necrotic debris, allowing the passage of a gastroscope into the cyst cavity, thus enhancing a wide and complete necrosectomy [20,21] .

More aggressive drainage, with endoscopic debridement un- der peritoneoscopy and complete necrosectomy, has been re- ported in patients with walled-off necrosis also in other experiences [22,23] with a high success rate of complete drainage and resolution of these collections which is also in accord with our results (72.7%). Pancreatic necrosis is often accompanied by pancreatic duct disruption; most experts strongly recommend as- sessing the integrity of the main pancreatic duct with pancreatog- raphy when drainage is considered. Successful treatment of coex- isting pancreatic duct disruption, stenosis or fistula, is paramount to prevent recurrence of the collection after the removing of the transmural drainage [24-27] . In our study, ten of our patients re- ceived pancreatic stent placement, and pancreatic duct stent place- ment was adopted in these patients with recurrence of PFCs or when imaging was suggesting pancreatic duct abnormalities. Per- cutaneous radiologic drainage [28] has also been reported as an ef- fective therapy for a selected subgroup of patients with pancreatic abscesses. In our study, six patients underwent combined percuta- neous drainage by interventional radiology because some anatom- ical areas, such as the paracolic gutter and the groin, were not ac- cessible by endoscopy.

In conclusions, pancreatic pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis are different diseases which require different management. Cor- rect categorization of a PFC is the first step to obtain correct man- agement and requires multidisciplinary care with close collabora- tion between endoscopists, surgeons, and interventional radiolo- gists. Drainage of sterile pancreatic pseudocysts by a double pig- tail plastic stent should be adequate. Additional placement of a transluminal naso-cystic catheter is mandatory in case of infective pseudocysts for rinsing. Finally, drainage of walled-off necrosis re- quires a wider cystogastrostomy or cystoduodenostomy which is obtainable by the placement of SEMS with additional and repeated endoscopic necrosectomy during the next days. The procedure is time-consuming and involves the use of both fluoroscopy and ul- trasonography in multiple steps. The performance of the procedure requires the assistance of anesthesia, and in our opinion, it should be performed in tertiary care centers where pancreatico-biliary ex- perienced surgeons, as well as interventional radiologists, are avail- able in the case of procedure-related complications.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Pietro Gambitta:Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.Anna Maffioli:Data curation.Jean Spiropoulos:Data curation.Antonio Armellino:Data curation, Supervision.Maurizio Vertemati:Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision Validation.Paolo Aseni:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Milan, Italy. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the sub- ject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Impact of EBV infection and immune function assay for lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric patients after liver transplantation: A single-center experience

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Intraoperative management and early post-operative outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease who underwent orthotopic liver transplantation

- Acute onset of autoimmune hepatitis in children and adolescents

- Liver stiffness as a predictor of hepatocellular carcinoma behavior in patients with hepatitis C related liver cirrhosis ✩

- Treatment and prognosis of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma based on SEER data analysis from 1973 to 2014