Acute onset of autoimmune hepatitis in children and adolescents

2020-03-03VrtislvSmolkOksnTkchykJiriEhrmnnEvKrskovMrtinZplkJnVolejnikov

Vrtislv Smolk , , Oksn Tkchyk , Jiri Ehrmnn , Ev Krskov , Mrtin Zplk , Jn Volejnikov

a Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacky University and University Hospital Olomouc, I. P. Pavlova 185/6, Olomouc 779 00, Czech Republic

b Department of Clinical and Molecular Pathology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacky University and University Hospital Olomouc, I. P. Pavlova 185/6, Olomouc 779 00, Czech Republic

Key words: Acute liver failure Autoimmune hepatitis Children Onset

ABSTRACT Background: Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a rare progressive liver disease, which manifests as acute hepatitis in 40%-50% of pediatric cases. This refers predominantly to spontaneous exacerbations of previ- ously unrecognized subclinical AIH with laboratory and histological signs of chronic hepatitis, or to acute exacerbations of known chronic disease. Only a few of these patients fulfill criteria for acute liver failure (ALF). Methods: Forty children diagnosed with AIH in our center between 20 0 0 and 2018 were included in this study. All of them fulfilled revised diagnostic criteria of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) for probable or confirmed AIH, and other etiologies of liver diseases were excluded. Patients were divided into two groups: acute AIH (A-AIH) or chronic AIH (C-AIH). Results: Acute onset of AIH occurred in 19/40 children (48%). Six of them fulfilled the criteria of ALF with coagulopathy and encephalopathy. Five of 6 children with ALF suffered from exacerbation of previ- ously undiagnosed chronic AIH, among which 4 children were histologically confirmed as micronodular cirrhosis. The remaining one patient had fulminant AIH with centrilobular necrosis, but no histological signs of previous chronic liver damage. We observed significantly lower levels of albumin, higher levels of aminotransferases, bilirubin, INR, IgG, higher IAIHG score and more severe histological findings in A- AIH than in C-AIH. No differences in patient age and presence of autoantibodies were observed between A-AIH and C-AIH. All children, including those with ALF and cirrhosis, were treated with corticosteroids, and are alive and achieved AIH remission. Liver transplant was not indicated in any patient. Conclusion: Rapid and accurate diagnosis of A-AIH may be difficult. However, timely start of immunosup- pressive therapy improves prognosis and decreases number of indicated liver transplantations in children with AIH.

Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a severe chronic inflammatory liver disease, predominant in females. It is characterized by hy- pergammaglobulinemia, presence of specific autoantibodies and a good response to immunosuppressive treatment. The cause of AIH is still not entirely elucidated. Initial presentation of AIH is highly variable, in 40%-50% of children AIH clinically and biochemically resembles acute hepatitis of other (mostly viral) etiologies [1] . Acute manifestation of AIH can also occur as a spontaneous exacer- bation of previously undiagnosed AIH with clinical and histological signs of chronic hepatitis. Only very few patients with acute AIH onset fulfill criteria of acute liver failure (ALF) with coagulopathy and encephalopathy without histological changes of chronic liver disease. Fulminant course of AIH occurs in approximately 6% of children with diagnosed and treated ALF [2] . In clinical practice, timely recognition of autoimmune ALF improves prognosis of pa- tients. The present study aimed to report the presentation of chil- dren with AIH at the time of diagnosis and their response to im- munosuppression.

Methods

Patients

Forty children diagnosed with AIH between 20 0 0 and 2018 were included in this study. AIH diagnosis was established according to the revised International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) criteria for probable (10-15 points) or confirmed ( > 15 points) AIH [3] and had to be concluded before the start of immunosuppressive treatment in all cases. Hepatitis A, B, C, cy- tomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infections were serologically excluded in all patients. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) status was not routinely examined in immunocompetent children older than 6 years. Clinical and biochemical examinations did not confirm autosomal recessive metabolic disorders connected with chronic liver damage, such as Wilson disease and alpha- 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Toxic and alcoholic liver damage were excluded anamnestically. At the time of diagnosis, we obtained anamnestic and clinical data and laboratory results. The follow- ing autoantibodies were examined: antinuclear antibodies (ANA), smooth muscle antibodies (SMA), antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA), liver/kidney microsome antibodies (anti-LKM), liver cytosol antibodies (LC1), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and soluble liver antigen antibodies (SLA). For ANA and SMA, titers 1:20 and above were considered positive; SLA, anti-LKM and LC1 were examined using the LIVER 7 DOT qualitative EIA immun- odot assay and evaluated semi-quantitatively (positive/weak posi- tive/borderline/negative) by visual comparison with a reference dot (cut-off). AIH was classified as type 1 (AIH-1) in cases with ANA or SMA seropositivity, or as type 2 (AIH-2) in LKM-1 or LC1 positivity.

Abdominal ultrasonography was performed in all patients. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was indi- cated at the time of diagnosis only in children with gamma- glutamyltransferase (GGT) level exceeding the upper reference limit more than two fold (i.e., GGT over 81.6 IU/L) to ex- clude the association of AIH with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) - an overlap syndrome. Diagnostic percutaneous non- targeted liver biopsy was done in all except one patient within 4 weeks since acute manifestation of hepatitis or after 6 months in silent chronic hepatitis. Histology examined activity of portal in- flammation, severity of lobular damage and grade of fibrosis ac- cording to Knodell et al. [4] . In one patient with ALF, histological finding was evaluated based on proposed specific criteria for au- toimmune ALF (AI-ALF) [5] .

Definitions

According to the onset of AIH, patients were classified as acute AIH (A-AIH) or chronic AIH (C-AIH). Biochemical and clinical find- ings in A-AIH strongly resembled acute viral hepatitis: alanine aminotransferase levels (ALT) were more than 10 times higher than the upper reference limit (i.e., > 350 IU/L) and total bilirubin ex- ceeded 22 μmol/L with conjugated bilirubin fraction over 50% of total bilirubin. C-AIH was characterized by non-specific or even lacking symptoms prior to diagnosis and by elevated aminotrans- ferase levels. Within the A-AIH group, we identified patients with ALF and histological findings of acute liver disease and patients ful- filling the ALF definition in originally unknown, but subsequently histologically confirmed, chronic liver disease. ALF was defined by biochemical markers of liver damage, presence of coagulopathy re- sistant to vitamin K and hepatic encephalopathy in children with- out previous liver disease. International normalized ratio (INR) cut- off was ≥1.5 in patients with hepatic encephalopathy and ≥2.0 without the presence of hepatic encephalopathy [2] .

Treatment

Patients were treated by corticosteroids, either in monotherapy (prednisone 2 mg/kg/day; maximum 60 mg/day) or in combination with azathioprine (1-2 mg/kg/day). After 4 to 6 weeks of initial treatment, the dose of prednisone was tapered (decrease by 5 mg after each 10 days) to a maintenance dose of 0.1-0.2 mg/kg/day. Azathioprine was administered continuously for 3 to 5 years de- pending on clinical condition and biochemical results of the indi- vidual patients. Therapy response was evaluated 6 weeks after the start of immunosuppression [6] . Disease remission was defined as normalization of aminotransferase levels and decrease of IgG. Con- trol liver biopsy was not performed within one year after treat- ment initiation in any patient.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by “R” freeware (R Foundation for Statisti- cal Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2017). To compare characteristics of two groups, we used Pearson Chi-square test (or Fisher test) for categorical variables and Student’s t -test (or Wilcoxon two-sample test) for continuous variables. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 40 patients with age range of 2-17 years were in- cluded in our cohort, females accounted for 65% (26 patients). Di- agnostic criteria of confirmed AIH were met in 26 children and cri- teria of probable AIH in 14 children. According to the autoantibody profile, 32 children had AIH-1 and 8 had AIH-2. Personal or family history of another autoimmune disease was positive in 10 children (25%): four patients had celiac disease (including 2 patients with A-AIH), two had immune thrombocytopenia and one had type 1 diabetes mellitus. One patient’s brother was followed with autoim- mune sclerosing cholangitis, two other patient’s mothers with au- toimmune thyroiditis and one patient’s mother with Crohn disease. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed ascites in 7 patients with A- AIH and acalculous cholecystitis in 4 patients with A-AIH. Hepatic copper concentration did not exceed 250 μg/g dry weight in any patient. MRCP at diagnosis was performed in 18 patients, always with normal finding on biliary ducts; overlap syndrome was not diagnosed in any of our patients during the follow-up.

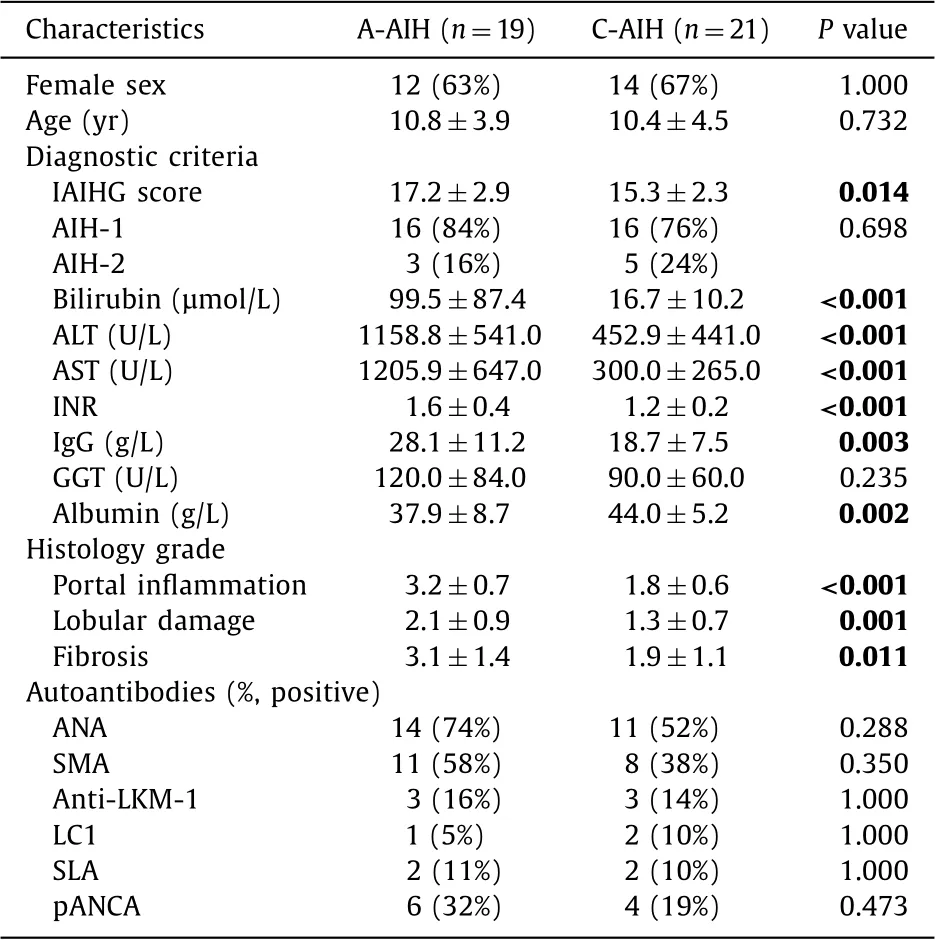

A-AIH was diagnosed in 19 children (48%). All except one of these patients were initially admitted to infectious diseases depart- ment due to suspicion of acute viral hepatitis, which was, however, swiftly excluded. The most common signs and symptoms included fatigue, loss of appetite, abdominal pain, vomiting, icterus and hep- atomegaly. Fourteen of 19 children with A-AIH (74%) underwent febrile viral infection of respiratory or gastrointestinal tract within one month before the hepatitis onset. Patients with A-AIH had sig- nificantly higher levels of aminotransferases, bilirubin, IgG and INR, and they had lower serum albumin levels than patients with C- AIH. A- AIH group had higher scores according to the IAIHG diag- nostic criteria than the C-AIH group ( Table 1 ).

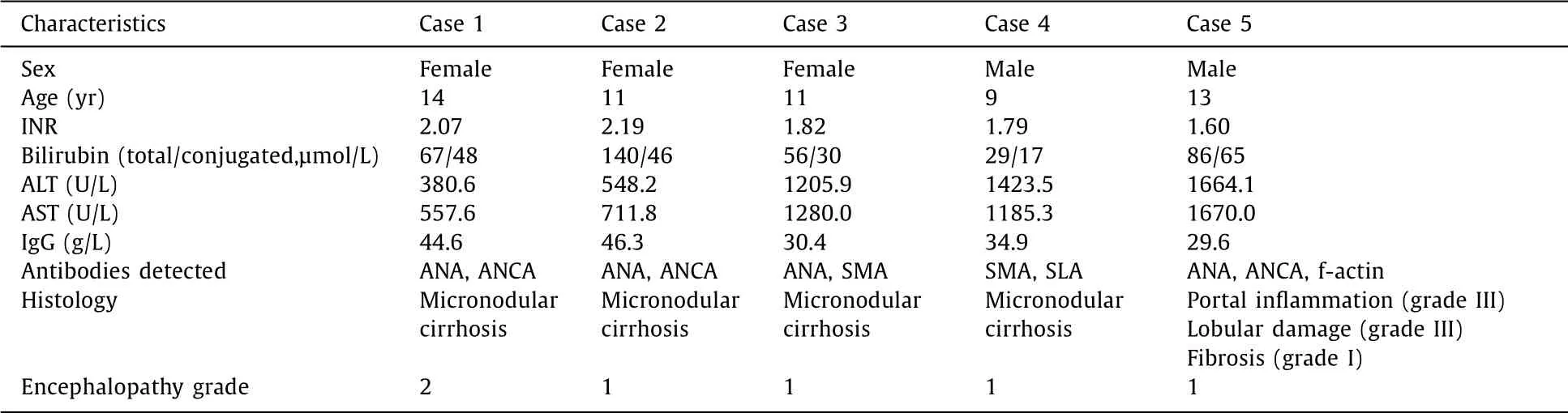

A total of six patients with A-AIH fulfilled the criteria for ALF. Five patients with A-AIH (26%) were classified as ALF follow- ing originally unknown chronic liver disease. Micronodular cirrho- sis was histologically confirmed in 4 of these patients ( Table 2 ). Another one patient fulfilled criteria of ALF with coagulopathy, hepatic encephalopathy and histological findings (see the follow- ing case). All of these patients developed hepatic encephalopathy within 28 days after the first clinical symptoms.

A 2-year-old male with history of preceding upper respira- tory tract infection was admitted due to fatigue, fever and ab- dominal pain to a regional pediatric department. He was subse- quently transferred to our tertiary center ICU with deteriorating level of consciousness and developed systemic inflammatory re- sponse syndrome (SIRS). The laboratory examination showed signs of acute hepatitis (ALT 1447 IU/L; AST 2741 IU/L) with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin 163 μmol/L, conjugated bilirubin 134 μmol/L) and coagulopathy (INR 2.01). His IgG level was ele- vated for age (14.2 g/L) and serum ANA antibodies were positive.

Table 1 Comparison of basic clinical and laboratory characteristics at the time of diagnosis in patients with A-AIH and C-AIH.

The patient had grade 2 encephalopathy with slow alpha and theta activity on electroencephalography (EEG). Abdominal ultrasound revealed acalculous cholecystitis. Histology detected lymphoplas- macytic periportal inflammation, massive hepatic necrosis (MHN) including centrilobular necrosis and presence of cholestasis with- out involvement of biliary ducts. These findings corresponded to the MHN5 pattern, which is typical for AI-ALF in adult patients [5] . Immunophenotyping of liver tissue demonstrated histiocytic acti- vation with high positivity of CD3+T -lymphocytes. After diagnosis of probable AIH and exclusion of different etiology leading to ALF, treatment with corticosteroids was administered, which led to the achievement of remission.

Contrarily, in 21 patients with silent C-AIH, no preceding febrile infections were reported. Elevated aminotransferase levels were found incidentally during examinations indicated either due to non-specific complaints, e.g. weight loss/failure to thrive, tiredness, abdominal pain or headache, or even due to unrelated indications.

None of the 40 patients with AIH suffered from complica- tions of portal hypertension. Among patients who underwent liver biopsy, histological finding of micronodular cirrhosis was found in 13 children (33%), including 8 children (42%) with A-AIH. Signifi- cantly higher grade of portal and lobular inflammation and fibrosis was observed in patients with A-AIH than C-AIH patients ( Table 1 ).

A 7-year-old female patient, the only one liver biopsy was not performed in, fulfilled diagnostic criteria for probable AIH-2 with presence of anti-LKM antibodies. She underwent viral respi- ratory infection three weeks before admission. Disease onset re- sembled acute hepatitis (ALT 1929 IU/L; AST 2035 IU/L; bilirubin 223 μmol/L) with coagulopathy (INR 1.54) and grade I encephalopa- thy. Plasma ammonia level was normal. On admission, she had leukopenia (3.2 ×109/L) and lymphocytopenia (0.58 × 109/L) but normal IgG level (9.5 g/L). MRCP showed acalculous cholecystitis and normal finding on biliary ducts. Aminotransferase levels de- creased within 2 weeks of corticosteroid therapy, but the patient developed aplastic anemia. She was transferred to Department of Hematology, where she achieved AIH remission on immunosupres- sive therapy. However, there was no bone marrow response af- ter 6 months of therapy, therefore she proceeded to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant from unrelated donor.

Thirty-three patients were treated by corticosteroid monother- apy, including 17 patients with A-AIH. Combined treatment was used in 2 children with A-AIH. Disease remission was achieved within 6 weeks in all patients with A-AIH and C-AIH, includ- ing those with cirrhosis. No complications of cirrhosis were ob- served, no surgical procedures including liver transplantation were required and all patients with cirrhosis are alive and followed with a stable liver condition.

Discussion

AIH is a rare disease with variable clinical, laboratory and histo- logical manifestations. The onset of acute AIH involves either acute exacerbation of previously unrecognized chronic liver condition, or acute liver disease without chronical changes on histology. Strin- gent clinical, biochemical and duration criteria for A-AIH diagnosis in children and adolescents are still lacking. In our cohort, approx- imately one half of the patients presented with acute disease on- set resembling initial signs and symptoms of viral hepatitis; this is in accordance with published data [1] . The majority of our pa- tients underwent respiratory or gastrointestinal viral infection. In such cases, even clinically insignificant infections may have trig- gered the acute exacerbation of previously silent chronic liver dis- ease and led to severe liver dysfunction.

Only one of our A-AIH patients had AI-ALF with ANA seroposi- tivity (AIH-1). However, previous studies of larger pediatric cohorts with AI-ALF reported predominance of AIH-2 [7,8] . AI-ALF is diffi- cult to diagnose and can be easily missed due to its rarity. Not all diagnostic criteria are necessarily met in fulminant AIH and con- trariwise, some of the criteria may be fulfilled in other causes of ALF; e.g., autoantibodies specific for both AIH types were present in 20% children with ALF of different etiology [9] . Probability of AIH increases with the number of detected autoantibodies [10] . Analogously, IgG levels may be normal in patients with AI- ALF [8,11] and increased in other causes of ALF [12] .

Table 2 Characteristics of patients with acute liver failure (ALF) following chronic liver disease.

Histology in children with AI-ALF is non-specific and does not help to differentiate between AI-ALF and other ALF. MHN4- MHN5 pattern is not more frequent in AI-ALF than in ALF of dif- ferent etiology [7] . In adult patients, presence of lymphoid fol- licles, a plasma cell-enriched inflammatory infiltrate and central perivenulitis was seen in addition to massive hepatic necrosis [4] .

In our patient with concurrent A-AIH and aplastic anemia, clin- ical and biochemical data suggested an autoimmune etiology and possible diagnosis of hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia (HAA). Lymphocytopenia at diagnosis could have indicated the risk of lat- ter hematologic complication. In contrast with published findings in HAA [13] , speckled ANA pattern was missing and liver histology was not performed in our patient. Successful treatment of hepati- tis may not prevent the development of aplastic anemia and sub- sequent need for hematopoietic stem cell transplant [14] .

In contrast with previous studies of adult patients [11,15,16] , no differences regarding age and autoantibody profile were observed between A-AIH and C-AIH groups in our pediatric cohort. Differ- ent proportions of ANA-positivity in A-AIH vs. C-AIH in adults were reported [15,17] . Significantly higher IgG levels in patients with A- AIH reflect an increased inflammatory activity and greater extent of fibrous changes. All evaluated histological markers were inferior in our patients with A-AIH. Liver cirrhosis was found in approxi- mately one third of children at the time of AIH diagnosis, more fre- quently in patients with A-AIH. Significantly higher IAIHG score in A-AIH patients might testify a more aggressive and longer course of disease prior to diagnosis. In a multicentric study reporting mild disease onset in the majority of patients, 20% of children had cir- rhosis at the time of diagnosis [18] , which is similar to our data. Trend to higher proportion of AIH-1 within the A-AIH group is also in accordance with literature [8] .

Six of our patients with A-AIH (32%) fulfilled the criteria for ALF. If definition of Asian Pacific Association for the Study of Liver for acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) [19] was applied, three of these patients would not fulfill the ALF criteria due to their bilirubinemia under 85 μmol/L. However, this definition was tai- lored to adult patients and it can underestimate the ACLF occur- rence in children. In a pediatric study of ACLF in developing coun- tries, Wilson disease and AIH were the most prevalent causes of chronic liver damage and hepatitis E and A infections served as ACLF triggers in endemic regions [20] . ACLF is associated with mul- tiorgan failure and mortality, where high Sequential Organ Fail- ure Assessment (SOFA) score and INR are negative predictors of outcome [21] . However, it is still unclear how to evaluate pedi- atric patients with previously undiagnosed chronic liver condition, who fulfill diagnostic criteria for ALF during the first acute man- ifestation [22] . Final conclusion is based upon histological finding, however, liver biopsy at acute phase may confer high-risk of severe complications and thus is frequently postponed.

Prognosis of A-AIH is mainly determined by timely start of im- munosuppression, which reduces the need for urgent liver trans- plantation and improves outcomes in children with AI-ALF [11] . Different etiology of liver disease must be strictly excluded prior to corticosteroid therapy, otherwise the administration of steroids may lead to increased morbidity and mortality [23] . Superior treatment response is associated with lower grade of encephalopa- thy [24] . All of our patients with A-AIH and C-AIH responded to corticosteroids and achieved initial disease remission regardless of their histology result.

This study has several limitations. First is the retrospective na- ture of the study, which included patients diagnosed within a long- time span. The number of patients is relatively small and they were recruited from a single-center. IAIHG score was used for pa- tient enrollment at the beginning of study; however, if validated simplified diagnostic criteria [24] were used, number of diagnosed AI-ALF cases may have been higher, as was shown both in children and adult patients [24,25] .

In conclusion, up to one half of pediatric AIH cases mani- fest as acute hepatitis and their diagnosis may be difficult - pre- dominantly in patients with fulminant disease course, where not all of the diagnostic criteria are necessarily met. Without timely diagnosis and immunosuppressive treatment, A-AIH can rapidly evolve into severe hepatic dysfunction with necessity of urgent liver transplantation. According to the published data, AI-ALF is more common than originally assumed. In children over 1 year of age fulfilling the ALF definition, AI-ALF diagnosis has to be considered after exclusion of hepatotropic infections and Wilson disease [7] .

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Pavla Kourilova for statistical analysis.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Vratislav Smolka:Data curation, Writing - original draft, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing-review & editing.Oksana Tkachyk:Data curation, Writing - original draft.Jiri Ehrmann:Methodology, Writing - original draft.Eva Karaskova:Data curation, Writing - original draft.Martin Zapalka:Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.Jana Volejnikova:Formal anal- ysis, Writing - original draft.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the European Re- gional Development Fund - Project ENOCH (CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/ 16_019/0 0 0 0868) and the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic -conceptual development of research organization (MH DRO; grant FNOL, 0098892).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Palacky University and University Hospital Olomouc.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the sub- ject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Impact of EBV infection and immune function assay for lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric patients after liver transplantation: A single-center experience

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Intraoperative management and early post-operative outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease who underwent orthotopic liver transplantation

- Liver stiffness as a predictor of hepatocellular carcinoma behavior in patients with hepatitis C related liver cirrhosis ✩

- Treatment and prognosis of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma based on SEER data analysis from 1973 to 2014

- Cholecystoenteric fistula with and without gallstone ileus: A case series