Factors associated with failure of enhanced recovery after surgery program in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy

2020-03-03XioYuZhngXioZhenZhngFngYnLuQiZhngWeiChenToXueLiBiTingBoLing

Xio-Yu Zhng , # , Xio-Zhen Zhng , # , Fng-Yn Lu , Qi Zhng , Wei Chen , To M , Xue-Li Bi , Ting-Bo Ling , c , *

a Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310 0 03, China b Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, the Second Aラiated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310 0 09, China c Key Laboratory of Pancreatic Disease of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou 310 0 03, China

Keywords: Enhanced recovery after surgery ERAS Pancreaticoduodenectomy Failure of ERAS Risk factors

ABSTRACT Background: The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol is an evidence-based perioperative care program aimed at reducing surgical stress response and accelerating recovery. However, a small propor- tion of patients fail to benefit from the ERAS program following pancreaticoduodenectomy. This study aimed to identify the risk factors associated with failure of ERAS program in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Methods: Between May 2014 and December 2017, 176 patients were managed with ERAS program fol- lowing pancreaticoduodenectomy. ERAS failure was indicated by prolonged hospital stay, unplanned read- mission or unplanned reoperation. Demographics, postoperative recovery and compliance were compared of those ERAS failure groups to the ERAS success group. Results: ERAS failure occurred in 59 patients, 33 of whom had prolonged hospital stay, 18 were readmit- ted to hospital within 30 days after discharge, and 8 accepted reoperation. Preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of ≥III (OR = 2.736; 95% CI: 1.276-6.939; P = 0.028) and albumin (ALB) level of < 35 g/L (OR = 3.589; 95% CI: 1.403-9.181; P = 0.008) were independent risk factors associated with prolonged hospital stay. Elderly patients ( > 70 years) were on a high risk of unplanned reoperation (62.5% vs. 23.1%, P = 0.026). Patients with prolonged hospital stay and unplanned reoperation had delayed intake and increased intolerance of oral foods. Prolonged stay patients got off bed later than ERAS success patients did (65 h vs. 46 h, P = 0.012). Unplanned reoperation patients tended to experience severer pain than ERAS success patients did (3 score vs. 2 score, P = 0.035). Conclusions: Patients with high ASA score, low ALB level or age > 70 years were at high risk of ERAS failure in pancreaticoduodenectomy. These preoperative demographic and clinical characteristics are im- portant determinants to obtain successful postoperative recovery in ERAS program.

Introduction

The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol, also referred to as fast-track surgery, is an evidence-based periopera- tive care program aimed at reducing surgical stress response and accelerating recovery [1,2] . Initiated by Kehlet in the early 1990s, ERAS has since been widely applied in several fields of surgery, including colorectal, gastric, hepatic, and pancreatic surgery [3-5] , and has been shown to be safe and effective for reducing com- plication rates, hospital costs, and the length of postoperative hospital stay [6] .

Currently, pancreaticoduodenectomy is considered the pro- cedure that provides the best curative effect for periampullary malignancy, especially pancreatic adenocarcinoma. It is a complex surgery and is associated with prolonged postoperative hospital stay and high morbidity and mortality [7] . The ERAS protocol for pancreaticoduodenectomy has been implemented in several hospitals and shown to be capable of reducing the duration of postoperative hospital stay without worsening of morbidity and mortality [8] . Using the comprehensive guidelines for pancreati- coduodenectomy published in 2012 by the ERAS Society founded in Sweden [9] , researchers have shown that the ERAS protocol can accelerate postoperative recovery of gastrointestinal function and promote mobilization [10] , reduce the incidence of complications such as delayed gastric emptying (DGE) [11] , and decrease hospital costs [12] . Our previous research has shown the similar results that ERAS is effective following pancreatic surgery [13] . However, we have noticed that a small proportion of patients fail to benefit from this program and require additional care. Identifying these patients is therefore crucial for improving efficiency. Although there are some studies focusing on factors associated with failure of ERAS in colorectal surgery [14,15] , there is no study on the application failure of ERAS in pancreaticoduodenectomy. This study aimed to identify the clinical predictors of failure of ERAS in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Methods

Patients and study design

Since May 2014, the ERAS program has been routinely imple- mented in patients undergoing open pancreaticoduodenectomy in Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. A retrospective study was performed including patients undergo- ing open elective pancreaticoduodenectomy who accepted the ERAS program between May 2014 and December 2017. Patients accepting prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stay ( > 48 h) on postoperative day 1 were excluded.

Demographic characteristics and preoperative data of these patients were extracted from the hospital database. The data included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, comorbidities, history of alcohol and tobacco use, results of liver function tests, and indications of surgery. Operative variables such as duration of surgery, operative blood loss, and blood transfusions were analyzed, as well as post- operative outcomes such as duration of postoperative hospital stay and unplanned reoperation, mortality, readmission, and complica- tions (during hospitalization or within one month after discharge). Flatus time, off-bed time, tolerance of oral food intake, and pain score (rated by numerical pain rating scale [16] ) following surgery were recorded as indices of postoperative recovery.

Postoperative complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [17] . The complications included pan- creatic fistula, chylous fistula, biliary fistula, DGE, surgical site infection, ascites, pleural effusion, hemorrhage, incision infection or fat liquefaction, thrombosis, and intestinal anastomotic leakage. Pancreatic fistula, DGE, and hemorrhage were defined according to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery defin ition [18-20] , and surgical site infection was defined according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition [21] . Biliary leakage was diagnosed if bile was seen to drain from the subhepatic drain and serum total bilirubin was above normal [22] .

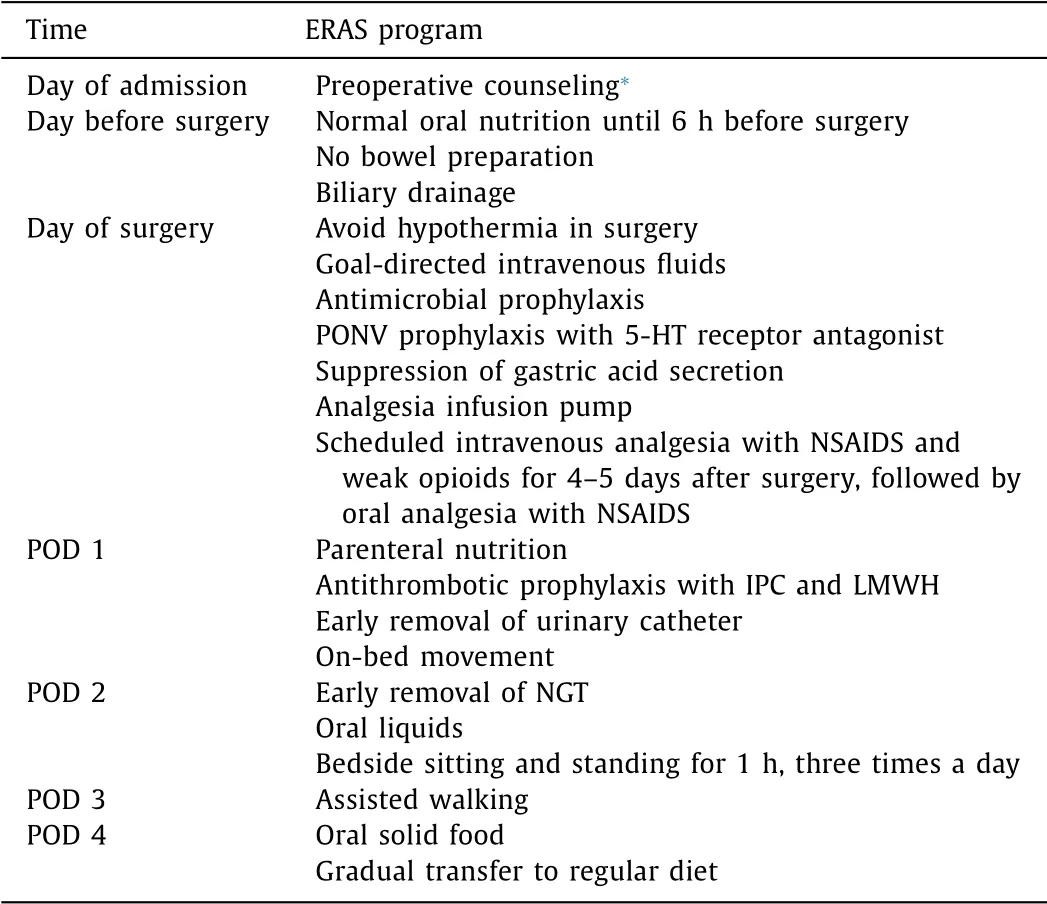

ERAS program

Our ERAS program is based on the 2012 ERAS Society guidelines for pancreaticoduodenectomy [9] , which includes the following elements: preoperative counseling, avoidance of bowel prepara- tion, biliary drainage, multimodal analgesia, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) prophylaxis, antimicrobial prophylaxis, antithrombotic prophylaxis, early removal of nasogastric tube (NGT) and urinary catheter, early oral food intake, and early mobilization ( Table 1 ). Multimodal analgesia involves analgesia infusion pump, scheduled intravenous analgesia with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and weak opioids, followed by oral analgesia with NSAIDS. Antithrombotic prophylaxis is achieved with intermittent pneumatic compression and low- molecular-weight heparin; the former is used for all patients and the latter for patients with Caprini score ≥3 [23] and no risk of hemorrhage. Early mobilization sets minimum targets for the first three postoperative days (POD), and aims at on-bed movement on POD1, bedside standing or sitting for accumulated 1 h on POD2, and assisted walking on POD3. Early removal of urinary catheter is defined as removal within 36 h after surgery, and early removal of NGT is defined as removal within 48 h. Early oral food intake refers to both intake of liquids on POD3 and intake of solid food on POD4. Intolerance to oral food intake refers to the need for fasting as a result of severe complications such as DGE. The compliance for each ERAS component of each patient was recorded as either accomplished or non-accomplished.

Table 1 The ERAS protocol.

Patients were discharged when they met the recovery criteria, which included absence of signs of infection, self-care indepen- dence, good function of vital organs, good pain control with oral analgesics alone, tolerance for solid food, passage of stool, good movement with assistance and good healing of wound [24] .

Failure of ERAS

In this study, the ERAS program was deemed a failure if one or more of the following was identified: prolonged postoperative hospital stay ( ≥20 days), unplanned readmission within 30 days after discharge, and unplanned reoperation caused by severe surgical complications such as grade-C pancreatic fistula before discharge. Patients with a failure recovery were divided into 3 subgroups according to the first occurred failure event.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data were summarized as mean ± standard deviation, median with interquartile range (IQR), or number and percentage. Continuous variables were compared using the unpaired Student’s t -test for normally distributed data or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher exact test. Ranked data were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Univariate and multivariate analysis were analyzed by Chi-square test and binary logistic regression model respectively. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 2 Demographic characteristics and operative factors associated with ERAS protocol failure.

Results

Demographics and operative variables

Among the 176 patients included in the study, 59 failed in ERAS program, of whom 33 had prolonged hospital stay, 18 were read- mitted within 30 days after discharge and 8 accepted unplanned reoperation because of severe complications.

Table 2 shows the demographic and operative characteristics of the patients. In prolonged hospital stay group, ASA score was remarkably higher ( P = 0.001), and 48.5% patients had III or IV score compared to the ERAS success group. Preoperative serum total bilirubin (TBil) and serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were significantely higher (131.9 μmol/L vs. 86.7 μmol/L, P = 0.047; 142 U/L vs. 90 U/L, P = 0.049), meanwhile serum albumin (ALB) was lower than the ERAS success group (35.2 g/L vs. 38.9 g/L, P < 0.001). In reoperation group, the mean age of patients were significantly higher than the ERAS success group (72 years vs. 62 years, P < 0.001), as well as the proportion of elderly patients (62.5% vs. 23.1%, P = 0.026). BMI and sex distribution were com- parable between each failure group and the ERAS success group. There was no significant difference among the groups in alcohol or tobacco use and in the prevalence of comorbidities (diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease). Indications for surgery and operative variables (duration of surgery and operative blood loss) were also comparable.

Four significant variables identified from the univariate analysis between prolonged hospital stay group and the ERAS success group (ASA score, TBil, ALT and ALB) were used for the multi- variate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, ASA score of ≥III (OR = 2.736; 95% CI: 1.276-6.939; P = 0.028) and ALB level of < 35 g/L (OR = 3.589; 95% CI: 1.403-9.181; P = 0.008) were significantly associated with prolonged hospital stay ( Table 3 ).

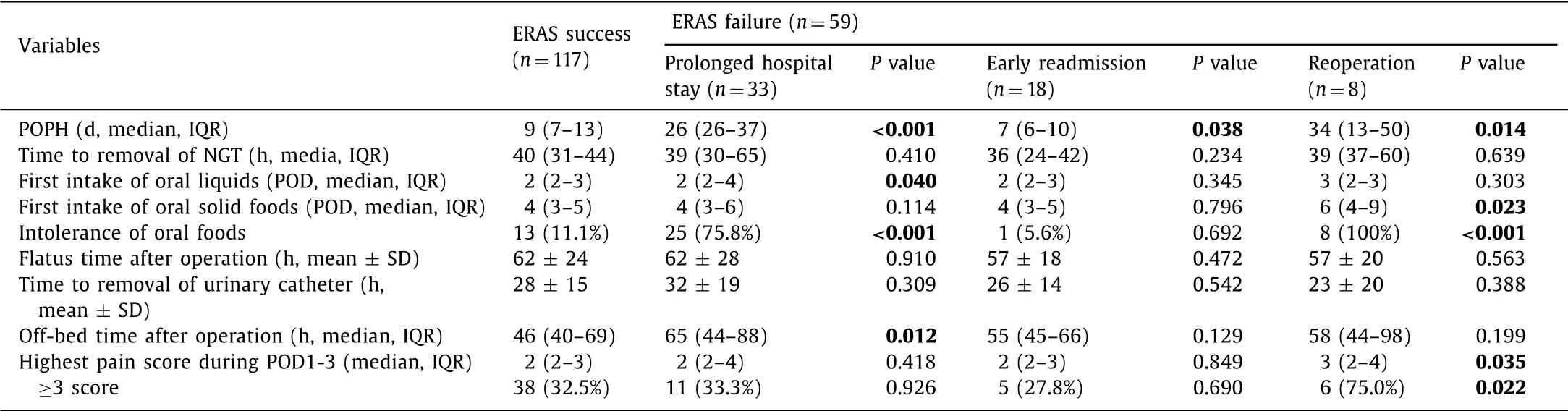

Postoperative recovery and outcomes

Table 4 compares the postoperative recovery features in each group. Postoperative hospital stay was obviously longer in pro- longed hospital stay and reoperation groups than the ERAS success group (26 days vs. 9 days, P < 0.001; 34 days vs. 9 days, P = 0.014). However, it was remarkably shorter in readmission group than that in the ERAS success group (7 days vs. 9 days, P = 0.038). The median time to removal of NGT was comparable between each failure group and the ERAS success group. Among the features of gastrointestinal function recovery, first intake of oral liquids delayed significantly in the prolonged hospital stay group than the ERAS success group ( P = 0.040), as well as first intake of solid food in reoperation group ( P = 0.023). Intolerance of oral food was markedly higher in both prolonged hospital stay and reoperation groups (75.8% vs. 11.1%, P < 0.0 01; 10 0.0% vs. 11.1%, P < 0.001). The off-bed time after operation in prolonged hospital stay group was significantly longer than the ERAS success group (65 h vs. 46 h, P = 0.012). The maximum pain score during POD1 to POD3 was no- tably higher in reoperation group than the ERAS success group (3 score vs. 2 score, P = 0.035). Flatus time after operation and time to removal of urinary catheter were comparable among the groups.

Table 3 Univariate and multivariate analysis for risk factors associated with prolonged hospital stay in ERAS program following pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Table 4 Postoperative recovery associated with ERAS protocol failure.

Table 5 shows the postoperative complications in each group. The distributions of complication grades differed significantly between each failure group and the ERAS success group (all P < 0.001). Grade B pancreatic fistula was markedly more common in prolonged hospital stay group and readmission group compared with the ERAS success group (36.4% vs. 3.4%, P < 0.001; 33.3% vs. 3.4%, P < 0.001). According to the definition of grade C pancreatic fistula, it only occurred in reoperation group, which resulted in a significant difference compared to the ERAS success group (62.5% vs. 0%, P < 0.001). DGE, particularly grade B DGE, was significantly critical in the prolonged hospital stay and readmission groups (24.2% vs. 2.6%, P < 0.001; 22.2% vs. 2.6%, P = 0.006). Meanwhile, the incidence of grade C DGE was significantly higher in prolonged hospital stay group (24.2% vs. 0%, P < 0.001). The morbidities of surgical site infection were significantly higher in all ERAS fail- ure groups of prolonged hospital stay, readmission and reopera- tion groups (12.1% vs. 0.9%, P = 0.008; 44.4% vs. 0.9%, P < 0.001; 62.5% vs. 0.9%, P < 0.001, respectively). Ascites and pleural effusion was significantly more prevalent in prolonged hospital stay group (30.3% vs. 12.0%, P = 0.011). Morbidities of chylous fistula, biliary fistula, hemorrhage, heart disease, thrombosis, intestinal anasto- motic leakage, and other infection were comparable among groups.

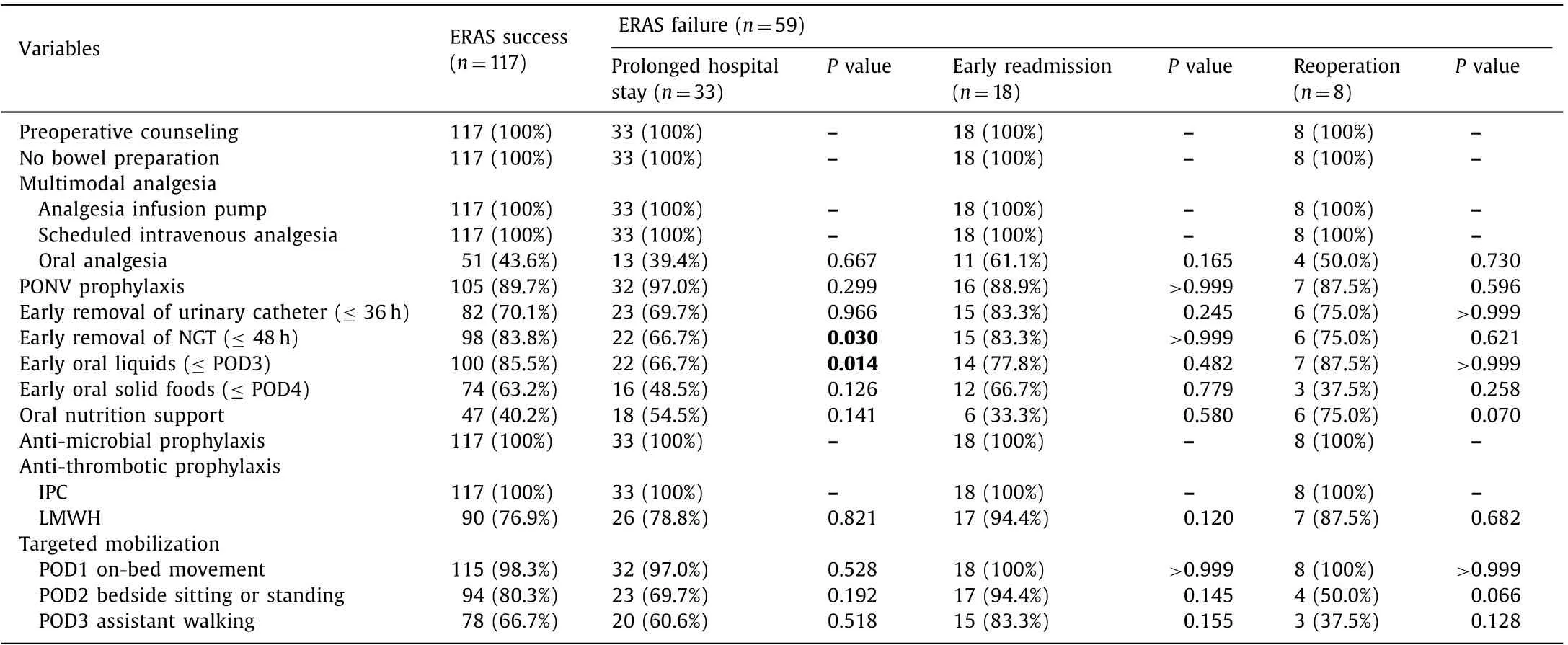

Compliance of ERAS core elements

Table 6 reveals the compliance of ERAS core elements in each group, including preoperative counseling, no bowel preparation, multimodal analgesia, PONV prophylaxis, early removal of urinary catheter and NGT, early oral liquids and solid foods, oral nutrition support, anti-microbial prophylaxis, anti-thrombotic prophylaxis and targeted mobilization. All the compliances of those elements between each ERAS failure group and the ERAS success group were comparable, except early removal of NGT and early oral liquids between prolonged hospital stay group and ERAS success group (66.7% vs. 83.8%, P = 0.030; 66.7% vs. 85.5%, P = 0.014).

Causes of unplanned readmission and reoperation

Table 7 shows the main causes of unplanned readmission and reoperation. The most common causes for readmission were postoperative pancreatic fistula (8/18), along with surgical site infections (5/18) and DGE (3/18). Among eight unplanned reoper- ations, five were caused by grade C pancreatic fistula, and other three were caused by biliary fistula, intestinal anastomotic leakage and hemorrhage, respectively.

Discussion

The ERAS program has advantages in pancreaticoduodenec- tomy. It can shorten the hospital stay and reduce hospital costs without compromising patient safety [8,12,25,26] . In our expe- rience, we also demonstrate the safety and efficiency of ERAS in pancreatic surgery patients [13] ; however, a small proportion of patients fail to benefit from the ERAS program following pancreaticoduodenectomy due to postoperative complications, which should not blame to ERAS program. Instead, many studies reported ERAS could reduce postoperative complications [11] . Thus, to identify the high-risk proportion is indispensable for further application of ERAS. Currently, few studies have examined the risk factors in pancreaticoduodenectomy. It is possible that the risk factors may be different with other surgeries, and we therefore analyzed the factors associated with failure of ERAS after pancreaticoduodenectomy in this study.

Table 5 Postoperative complications associated with failure of ERAS.

Table 6 Compliance with ERAS core elements.

Table 7 Causes of unplanned readmission and reoperation.

According to the definition described above, the rate of pro- longed hospital stay was 18.8% (33/176) in this cohort, the rate of unplanned readmission was 10.2% (18/176), and the rate of unplanned reoperation was 4.5% (8/176).

Pre- and intra-operative univariate analysis, attempting to identify patients who tend to fail ERAS protocol, showed that high ASA score, TBil and ALT level and low ALB level are risk factors as- sociated with prolonged hospital stay. The ASA scale is commonly used to evaluate preoperative health status, mainly judged by sys- temic disease and its functional impediments [27] . In our result, an ASA score of III/IV and an ALB level lower than 35 g/L were independent risk factors, which stand for a severe physical status and indicate a poor metabolic and nutritional status. Metabolic and nutritional status have been reported as a predictive factor for outcome in patients with pancreatic cancer, affecting both overall survival and disease free survival, and the most common parameter analyzed is ALB [28] . A TBil level of > 80 μmol/L and an ALT level of > 100 U/L were also related to prolonged hospital stay, reflecting biliary obstruction and impaired liver function. It has been revealed that severe jaundice increases postoperative complications by altering immunologic function and damaging renal function [29] . Therefore, patients with high ASA score and low ALB level should be paid more attention on the postop- erative complications, which could lead to prolonged hospital stay.

As to unplanned reoperation, univariate analysis showed that the age above 70 years was the only risk factor. Elderly patients should be alert to severe complications such as grade C pancreatic fistula and intestinal anastomotic leakage. Although it may show no improved postoperative outcomes, many previous studies have indicated that ERAS is feasible and safe for elderly patients [30] . Therefore, for the majority of patients undergoing pancreatico- duodenectomy, it is unnecessary to exclude specific patients from ERAS protocol, however, a modified ERAS program for the elderly patients, with additional perioperative care, could be considered in the future.

Postoperative complications are acknowledged to be the main reason for ERAS failure. In the present study, the commonest post- operative complications accounting for prolonged hospital stay and unplanned readmission were grade B pancreatic fistula, DGE and surgical site infections, which count for 36.4%, 48.4% and 12.1% respectively in prolonged hospital stay group and 33.3%, 27.8% and 44.4% respectively in readmission group. As to unplanned reoperation, grade C pancreatic fistula and surgical site infections were the main contributors.

Thus, delayed recovery of gastrointestinal function and surgical complications that directly related to the technical aspects of the operation, were the major reasons for failure of ERAS in pancreati- coduodenectomy. Up to now, there are no acknowledged medicine strategies for avoiding the complications of pancreatic fistula and DGE after surgery [31] . However, the need for readmission due to infection can be reduced by education, antimicrobial prophylaxis, and reducing the rate of discharge with drainage tube. And it is reported that the ERAS protocol can reduce healthcare-associated infections [32] .

DGE, as the severest consequence of delayed recovery of gas- trointestinal function, is another critical aspect to be improved. In fact, several researches had reported that ERAS protocol in- cluding early removal of NGT, early oral foods and oral nutrition support could reduce the morbidity of DGE [11,25] . Furthermore, intravenous fluid restriction, which could decrease the incidence of intestinal edema and pancreatic anastomotic complications, is another item of ERAS to promote the resumption of gastrointesti- nal function [33,34] . It is reported that pancreatic fistula, biliary fistula and surgical site infection were the risk factors of DGE, which reaffirmed the significance of improving surgical technique and expertise.

In our research, postoperative recovery and compliance anal- yses showed delayed diet resuming and off-bed mobilization in prolonged hospital stay patients, especially early removal of NGT and intake of oral liquids, which were closely related to postoperative outcomes and could serve as predictors of prolonged hospital stay in the early postoperative period. Also, pain score was increased in reoperation patients, which suggested surgeons to be alert to severe complications when elderly patients presenting a pain score of 3 or higher and delayed diet resuming.

There were certain limitations to our study. We have not identi- fied the risk factors associated with unplanned readmission mainly caused by pancreatic fistula and surgical site infection, which may suggest subsequent anti-microbial treatment after discharge.

In conclusion, preoperative ASA score ≥III and serum albu- min level < 35 g/L were associated with prolonged hospital stay in ERAS following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Patients with age older than 70 years were at high risk of unplanned reoperation. Delayed diet resuming and off-bed mobilization within 3 days after surgery were significant predictors of prolonged hospital stay. Delayed diet resuming and pain score higher than 3 were pre- dictors of unplanned reoperation. These predictors are important determinants to obtain successful postoperative recovery in ERAS program.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiao-Yu Zhang:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal anal- ysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft.Xiao-Zhen Zhang:Con- ceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writ- ing - original draft.Fang-Yan Lu:Conceptualization, Data cura- tion, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft.Qi Zhang:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investi- gation, Writing - original draft.Wei Chen:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft.Tao Ma:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investi- gation, Writing - original draft.Xue-Li Bai:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing.Ting-Bo Liang:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Project of Medical and Health Technology Platform of Zhejiang Province ( 2017RC003 ), the National High Technology Research and Development Pro- gram of China ( SS2015AA020405 ), the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China ( 81871925 ), the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China ( 81672337 ), the Key Innovative Team for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer of Zhejiang Province ( 2013TD06 ), the Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China ( 81530079 ), and the Key Research and Development Project of Zhejiang Province ( 2015C03044 ).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the sub- ject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Impact of EBV infection and immune function assay for lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric patients after liver transplantation: A single-center experience

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Intraoperative management and early post-operative outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease who underwent orthotopic liver transplantation

- Acute onset of autoimmune hepatitis in children and adolescents

- Liver stiffness as a predictor of hepatocellular carcinoma behavior in patients with hepatitis C related liver cirrhosis ✩

- Treatment and prognosis of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma based on SEER data analysis from 1973 to 2014