DIY Corpora for Vocabulary Learning

2020-02-02SimonSmith

◎Simon Smith

INTRODUCTION

One of the principal applications of corpora in English language teaching and learning has been the compilation of vocabulary lists for student use.West’s General Service List (GSL; 1953)was based on a painstaking (manual)corpus analysis of frequency and range (Gilner, 2011), and almost all subsequent lists, whether of general English (College Entrance Examination Center, 2002), academic English (Coxhead,2000)or specialist domains have been derived directly or indirectly from corpora.Learners need to acquire words that are both frequent in the language and occur across a range of texts, and the use of corpora can furnish lists that satisfy these frequency and distributional requirements.

There is a core English vocabulary which dominates many genres and styles, and it is of course important for learners to acquire this vocabulary.The General Service List, even decades after it was compiled, was found to cover 90-92% of tokens in three children’s fiction texts (Hirsh and Nation, 1992), and 76% of tokens in the Academic Corpus, used by Coxhead (2000)to create the Academic Word List (AWL).This list, in its turn, is intended by Coxhead to represent a core “academic” vocabulary, and forms the basis for a host of academic vocabulary activities, textbooks and learning websites, as well as inspiring other academic wordlists that followed.

In many professional and academic contexts, however, learners wish to acquire the vocabulary and terminology of their own specialist domain, which by its nature will not emerge as salient in a general corpus or appear on a wordlist derived from the same.A great deal of prior work has been done on the construction of corpora in specialist domains, and the compilation of wordlists based on them; some of this work will be surveyed in the Literature Review section.In that section, I will also consider wordlists that incorporate multi-word units (MWUs), which are of importance in the acquisition of specialist language.

The present paper proposes a data-driven learning (DDL)approach to the creation of specialist vocabulary lists and terminological resources.University students whose first language is not English are asked to construct a corpus from learning materials and texts supplied by their specialist subject tutors.They then expand the corpus, using software tools provided, to add related texts from the Web.Next, they generate a list of the salient words and MWUs from their extended specialist corpus.Finally, they incorporate selected words and terms from the lists into their own personalized vocabulary portfolio, where they also include definitions, corpus/dictionary examples, and any other information they wish to record.The portfolio is in a spreadsheet format which they can conveniently consult and add to throughout their course (and indeed into the future).

The following research questions will be addressed:

1.How effective are corpus construction and the compilation of vocabulary portfolios by learners in the acquisition of specialist terminology?

2.What are learners’ perceptions on learning vocabulary via corpus construction and vocabulary portfolios?

These questions are addressed by means of(i)pre- and post-tests which attempt to discover to what extent the interventions helped learners in the acquisition of domain-specific vocabulary, and(ii)a questionnaire-based analysis of the perceptions of the learners about the approach.

Organization of the Paper

The next section sketches the DDL approach and relevant prior work, attempting to show how language in general (and vocabulary in particular)is more likely to be retained when the learner engages with the corpus and portfolio construction, making decisions about selection and inclusion along the way.I also look at the ways corpora have been used to create wordlists and vocabulary resources.

In the Methodology section, I first summarize a pilot study (Author, 2015)in which a small number of students constructed their own corpora and investigated concordances and collocational patterns, but were not asked to create vocabulary portfolios.

I then give further details of the main intervention reported in this paper, as well as the pre- and post-test procedures that were used to establish its effectiveness, and the qualitative perceptions study.A Results and Discussion section will present and analyse the findings from these tests, as well as conclusions drawn from participant questionnaire responses.Limitations of the study, conclusions, and directions for future research will then be presented.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In this section, I first present some of the literature on corpus consultation by learners,and the pros and cons of such a DDL approach.I then look at the ways corpora have been used professionally to produce wordlists.A third and final subsection describes prior work on corpusconstruction(rather than simpleconsultation)by learners, paving the way for work on DIY corpus-based vocabulary resources.

Background to DDL

The use of linguistic corpora in language learning often takes the form of concordance analysis by students, or data-driven learning (DDL).In a parallel to data-driven computational algorithms, DDL attempts to impart linguistic knowledge by making available samples of authentic language, from corpora, and inviting language learners to discover usage patterns for themselves.The approach invites learners to tease out patterns from authentic text, and test their own linguistic hypotheses in the manner of a mini research project;it has an intuitive appeal to teachers who favour student-centred or inductive learning.Johns (1991), who coined the term, likens the language learner (on the DDL model) to a researcher, analysing target language data and becoming familiar with the language through the regularities and consistencies encountered.Johns (1991: 2), famously, goes on to claim that “research is too serious to be left to the researchers”.

What is important to note about this use of corpora in language learning is that the data areauthentic(because a corpus contains examples of real language in use, as opposed to the possibly inauthentic examples in a textbook), and that they arerepresentative(because a corpus of, say, billions of running words, will offer plenty of examples, while a dictionary might only have a few).As Stubbs (2002: 221) has it, corpus linguistics is both “inherently sociolinguistic”, in that the data are authentic, and “inherently quantitative […] mak[ing]visible patterns which were only, if at all, dimly suspected”.

An early and often cited set of DDL materials is Johns’s kibbitzers, of which an excellent example is presented in the 1991 paper.The title of the paper is ‘Should you be persuaded’, for the reason that it presents first an activity which challenges the reader to identify (from concordance data) the several senses of the word “should”, and then another activity which invites us to characterize the difference between “persuade” and “convince”,again by appealing to supplied corpus evidence.Johns’s kibbitzers (to be found at http://www.lexically.net/TimJohns/) inspired the MICASE kibbitzers, the work of John Swales and colleagues (Regents of the University of Michigan 2011), archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20111008033810/http://micase.elicorpora.info/micase-kibbitzers.A number of other websites and books, including Tribble & Jones (1990), the now out-of-print Thurstun& Candlin (1997), Reppen (2010), and Lamy & Klarskov Mortensen (2012) offer suggestions for DDL tasks.A collection of DDL resources has been gathered by Neufeld (2012)at http://www.scoop.it/t/data-driven-language-learning/.

DDL has not, however, become widely accepted as a language teaching approach.Boulton (2008) considers a number of reasons as to why this should be so, concluding that“In a nutshell, learners and teachers simply aren’t convinced”.It is the case, too, that in its default and rather prosaic consultation mode, DDL can consist of entering keyword queries at a computer keyboard and reading through lines of concordance output (or reading printed lines).As Kilgarriff et al.(2008) put it, “The bald fact is that reading concordances is too tough for most learners.Reading concordances is an advanced linguistic skill.”

Students new to corpus studies are sometimes uncomfortable with the alarming physical appearance of KWIC concordances (Lamy & Klarskov Mortensen, 2007).Boulton (2009)summarizes what others have said about the problem of learning from truncated sentences in KWIC output, citing on the one hand Johns (1986:157) who claims that learners are quick to“overcome this first aversion”, and on the other hand Yoon and Hirvela (2004: 270), who report that 62% of their students perceive sentence truncation as a “difficulty”.

Tim Johns’s (1991) idea that language learning should be based on research is echoed by Bernardini (2000), who treats DDL as a voyage of discovery, serendipitous in nature, where the learner may be sidetracked along the way.Lee & Swales (2006)characterize the approach, less glowingly, asincidentalism(whilst admitting to having adopted it in their own study).Whilst supporting the approach, Adel (2010: 46), in an article on the use of corpora to teach writing, claims that students can be overwhelmed by the sheer amount of data available, and that “teacher-guided settings and clearly defined tasks” help them out of the “maze”.In her development of the work of Johns,Gavioli (2009: 47) suggests that in order to allay potentialembarrasdechoix, “autonomy needs to be guided and educated”.Vincent (2013) also refers to the desirability of taking a guided discovery, rather than a purely inductive and serendipitous, approach—particularly with students new to DDL.

Gavioli also notes (p.44) that students are particularly motivated by working with their own corpora, and that “creating and analysing corpora is something that students may take very seriously”.The students in the present study were, as has been noted, tasked with constructing their own corpora, and developing wordlists based on them.I will briefly survey prior work on learner corpus construction in the final subsection of this literature review.Next,however, I look at corpus-informed wordlists and the surrounding literature.

Corpora and Academic Wordlists

The General Service List (GSL), as is evident from its name, lists vocabulary that was(in 1953) in general use, and does not specifically target academic needs.Through the 60s and 70s, several new academic wordlists emerged.These wordlists were generally compiled by teachers, without the aid of computers, to meet specific local needs, and were based on corpora of textbooks and other academic writings; these include Campion & Elley (1971),Praninskas (1972), Lynn (1973), Ghadessy (1979).In 1984, Xue & Nation combined the four most recent of these lists to form the University Word List.Coxhead (2000) perceived the need for an academic wordlist based on a larger corpus and more principled inclusion criteria,and her well-known AWL was generated from a 3.5m word Academic Corpus.The words admitted to the list were subject to specialized occurrence (not in the GSL) and range (crossdisciplinary reach) criteria, and were required to occur at least 100 times in the Academic Corpus.The list is organized by word family, not by word token or lemma.Thus, ‘introduction’and ‘argumentation’, which one might expect to find on a list of academic words, are both excluded because ‘introduce’ and ‘argue’ exist in the GSL in non-academic senses.

The AWL is widely known in the academic English teaching profession, and there are a number of coursebooks and English learning websites that exploit it as an inventory of academic vocabulary.Other general academic wordlists have since been established, chief among which are the New Academic Word List (NAWL, based on the Cambridge English Corpus; Browne, Culligan, & Phillips, 2013), and the Academic Vocabulary List (AVL,based on the COCA corpus; Gardner & Davies, 2013).Some learning materials have been developed around the AVL, mainly on the compilers’ websites vocabulary.info and wordandphrase.info, but they are not as extensive as those of the AWL.

The new lists, unlike AWL, do not conflate all derived forms into one word family.Research findings (e.g.Schmitt and Zimmerman, 2002: 158) indicate that the acquisition of one member of a word family does not necessarily facilitate the acquisition of a second member, as with the examples of ‘argue’ and ‘introduce’ noted above; or the problematic inclusion of both ‘briefed’ and ‘brevity’ under the AWL headword ‘brief’, where two entirely different word senses are involved.

The corpora used to compile the academic wordlists are partitioned by academic discipline: AWL is divided into four overarching disciplinary sections (Arts, Commerce, Law,Science), each of which is further subdivided into 7 subject areas.No attempt is made to assign the words themselves to disciplines, however.Hyland & Tse (2007) point out that some senses of words (and indeed certain derived forms within AWL word families) are more likely to occur in one discipline than another.Thus, for example, the form ‘appendixes’ probably only occurs in biological or medical writing, while other members of the ‘appendix’ word family, including the alternative plural ‘appendices’, will occur in many disciplines.The senses of other AWL word families, for example ‘revolution’, are entirely different in say politics and engineering, but the wordlist offers no way to tease the senses apart.

Hyland & Tse (2007) investigated the distribution of AWL words in their own academic corpus, and found considerable variation in the ways words are used across the disciplines.For example, ‘process’ was far more likely to act as a noun in the sciences, with nominalization being more common there generally.Members of the word family ‘analyse’are used differently across disciplines, often participating in highly domain-specific multiword forms such as ‘genre analysis’ and ‘neutron activation analysis’.Hyland & Tse (2007:247) conclude that “A growing body of research suggests that the discourses of the academy do not form an undifferentiated, unitary mass, as might be inferred from such general lists as the AWL, but constitute a variety of subject specific literacies.” In line with Hyland & Tse’s arguments, a number of discipline-specific academic wordlists have emerged.For example,the Medical Academic Word List (Wang et al., 2008) is based on a corpus of medical research articles; the Engineering Wordlist, the work of Mudraya (2006), comes from engineering textbooks.

Like AWL, NAWL and AVL, these specialized lists do not include multi-word units(MWUs).There are at least two lists of academic MWUs: the Academic Formulas List (AFL;Simpson-Vlach & Ellis, 2010), and the Phrasal Expressions List (Martinez & Schmitt,2012).These, however, contain general academic MWUs, rather than discipline-specific terms.This leaves ESAP practitioners with little to go on in terms of discipline-specific MWUs.

The present research addresses these issues in that learners were encouraged to include both single word and multi-word items in the wordlists (vocabulary portfolios) they created,specific to their own discipline.

Students select texts and websites related to their specialism or area of interest to generate the corpus and portfolio, and need to make decisions about what to include, so the task is an authentic one in terms of the TBL characteristics noted by Van den Branden(2013:629)—much of the language studied by learners is acquired from authentic sources such as learning materials supplied by subject tutors.Learners acquire language—both the terminology of their subject, and the contexts in which the terms are used—as their research proceeds; they truly “learn language by using it”, in Van den Branden’s words.

Construction of Corpora by Learners

We now return to data-driven learning.The approaches to DDL described in the first subsection of this literature review involve theconsultationof corpus resources.It has been claimed that corpusconstructionby learners, followed by consultation, may afford better learning opportunities (Aston 2002).The process of creating a corpus, according to Tyne(2009) inculcates a sense of ownership in the learner and therefore has a motivational impetus, and Lee & Swales (2006) emphasized this “ownership” in an apparently successful bid to get their students to engage with corpus construction, despite the students’ initial reluctance.Zanettin (2002) had learners compile a corpus from the web, and analyse it with Wordsmith Tools, reflecting (p.7) that “constructing the corpus was as useful as generating concordances from it”.Charles likewise highlights (2012: 101) the “truly revelatory moment when they see the patterns appear before their eyesintheirowndata” [emphasis in original].

Moreover, the process of compiling the corpus may lead to the acquisition of not only language, but also useful transferable skills, including IT and problem-solving competencies(Boulton 2008; Jackson 1997).Once the corpus is constructed, some students may be sufficiently motivated to consult it and add to it when needed (Charles 2014).Lee & Swales(2006) report that some of their students even purchased their own copies of Wordsmith Tools, indicating a commitment to continuing with corpus construction and analysis in the future.

Castagnoli (2006) had translation trainees use the BootCaT toolkit (Baroni & Bernardini,2004) to generate web corpora on specific topics, and extract lists of terms, which could be used to compile glossaries and term databases.The students found that a larger number of relevant terms could be extracted when the domain chosen was highly specialized.By way of assessment, the students were given a technical translation task, and were asked to prepare for it by building a web corpus in the relevant domain, and extracting from it a glossary of terms.

Author (2011) extended Castagnoli’s approach to non-specialist language learners in a Taiwan university.Corpus construction was seeded or bootstrapped from a set of user-supplied keywords: first a search engine module found web pages which were “about” the keywords,then other BootCat software components extracted text from the web pages and generated the corpus.Students were asked to construct and consult a corpus relating to their own academic discipline, and provide analysis and commentary, with one student, for example, commenting:

Creatingaspecializedcorpuscouldbeusefulwhenitcomestoresearchingaparticular subjectorlearningasubjectinEnglish.Itisusefulbecauseofthedifferentresultswhichare muchmorerelevantthansearchingonamuchmoregeneralEnglishcorpus.

METHODOLOGY

Pilot Study

A group of six Accounting and Finance for International Business (AFIB) students undertook a corpus construction task as part of an in-sessional English for Academic Purposes (EAP) class.The students were final year direct entry international students, having completed the first two years of their course at an institution in their home country (in these six cases, China).An IELTS score of 6.5 is required to enter the year, and all were at this level.

The study was conducted over a period of four teaching weeks, and is reported in greater detail by Author (2015).In the first two lessons, an introduction to the use of corpora and the reading of concordance lines was given.In weeks 3 and 4, students constructed and consulted their own corpora, based on texts and learning materials that had been made available by their AFIB module tutors.They were not asked to make vocabulary portfolios, as with the present study, but they did study concordances and consult Word Sketches (one-page summaries of word usage) in the Sketch Engine corpus analysis tool (Kilgarriff et al 2004), focusing on academic and accounting words and terms from their corpora.

The students were asked (at the end of a homework task sheet) whether the Sketch Engine was useful for (Q1) English study and/or for (Q2) AFIB study, and (Q3) whether they found the work interesting.Two of the six students responded, both making only positive comments: the approach was useful for EAP and AFIB study, and Student 1 commented that it was “interesting and amazing”.Student 2 wrote that “the process of create my own corpora was very enjoyable and makes me sense of accomplishment”, confirming the findings of others reported in the Literature Review section that the process can be motivating and engaging.

Despite the indication of satisfaction, it seemed to the researcher that the students needed more of a sense of purpose when consulting their DIY corpora.They seemed quite content to explore the corpora in a more or less serendipitous way, but like Adel (2010) and Vincent (2013), I felt that the discovery process required more clearly articulated tasks and learning outcomes.The requirement in the main study to create vocabulary portfolios met that need, as well as providing a useful reference resource for students.

Participants

This study constituted a larger scale, quantitative follow-up to Author (2015), and was run over a period of one (11-week) second semester.The entire cohort of AFIB topup students (n=94), consisting of 4 EAP class groups, participated in the study.With the exception of either one or two members of each class, all were L1 Chinese speakers; in other respects, the composition was the same as for the pilot study.Two of the class groups(EFA3 and EFA4) acted as control groups, and two (EFA1 and EFA2) as experimental groups, these last being taught by the researcher.The experimental group classes were conducted in a computer lab, and in addition to the normal EAP work specified by the syllabus, students were given the opportunity to do corpus-based vocabulary work, as described in the Intervention section, for an average of 20 minutes per two-hour weekly class.

The control groups were each week given a list of financial domain vocabulary to study in their own time.The lists were generated from Accounting & Finance corpora, created by the researcher in the same way as the students in the experimental groups created their own vocabulary portfolios (as described inCorpusConstructionbelow).

Two sub-domains of vocabulary were studied, related to two of the financial modules that all participants were studying in their home department.EFA1 (experimental group)and EFA3 (control) focused on Management Accounting (ACC), while EFA2 and EFA4 explored the vocabulary of International Finance (FIN).ACC and FIN are two of the three content modules followed by AFIB students in the second semester.

Figure 1 Configuration of participant groups

The participant configuration is shown in Figure 1.It was predicted that

H1.All groups will perform better in the post-test than they did in the pre-test.

H2.EFA1 and EFA2 will improve more overall in the post-test than EFA3 and EFA4.

为增强地下水管理相关重点制度的刚性和约束力,确保重点制度的落实,应当结合地下水管理专门法规的制定,完善行政处罚措施。比如,增加凿井施工单位在凿井施工过程中主要违法行为的处罚;明确地下水源热泵系统建设中破坏地下水行为的处罚的规定;完善不封闭自备井应承担的法律责任等,增强制度的操作性及强制性。

H3.EFA1 will improve more than EFA2, and EFA3 more than EFA4, on Management Accounting items.

H4.EFA2 will improve more than EFA1, and EFA4 more than EFA3, on the International Finance test items.

It would have been possible to configure the groupings in a simpler way.For example,all groups could have been exposed to both of the domain vocabularies, with two experimental group classes creating corpora and the two classes using lists.This would have entailed,however, that the vocabulary being acquired from combined module resources would not have represented a coherent domain; I wanted the students to benefit from vocabulary resources that aligned with a plausible subject of study (one of their content modules) and were perceived as such.

Pre- and Post-tests

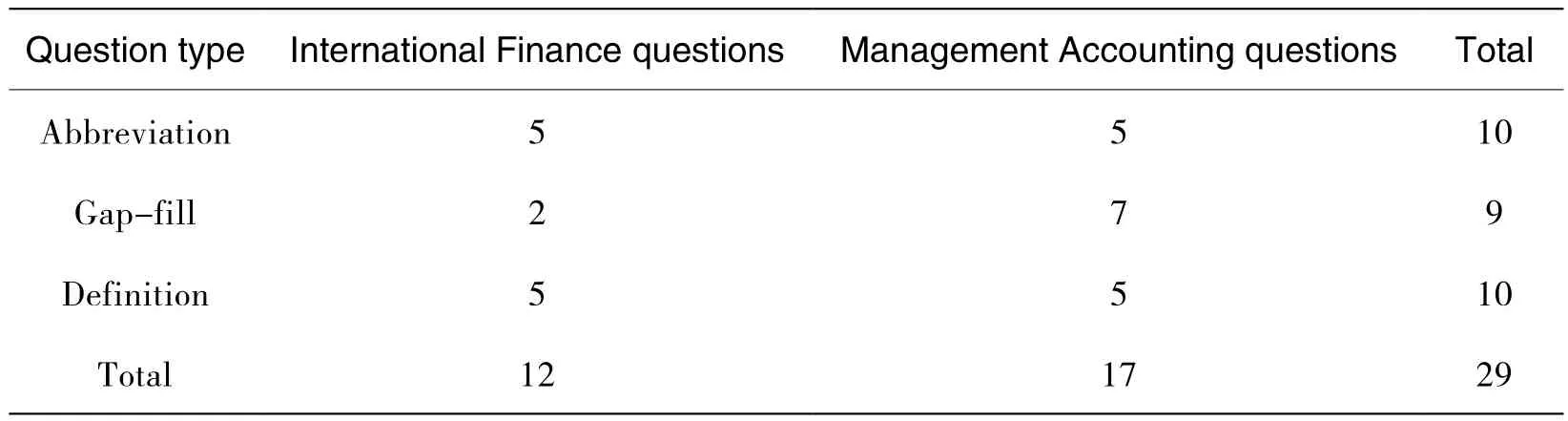

A pre-test, designed to test participants’ knowledge of vocabulary in both the financial sub-domains, was administered at the start of the semester.The test included abbreviation items such as NPV and IMF, which the participants were asked to expand (in this case, to“net present value” and “International Monetary Fund” respectively).There were also 10 gap-fill questions, for example “The bonds are trading at only 40% of f___ v___”, to which the correct answer would have been “face value”.This was followed by 10 definitions,such as “a legal way of reducing the amount of tax a person or company would normally pay:T____ a____”.This particular item should be answered “tax avoidance”.The distribution of questions types and domains is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Distribution of question types in pre/post-tests

In the pre-test, half of the items belonged to the sub-domain of Management Accounting, the other half to International Finance.To select the test terms, I constructed corpora in the same way as the students did for the interventions(described below) and selected the most salient vocabulary items; these corpora were also used to generate the vocabulary lists and quizzes for the control groups.A very similar post-test, containing the same items as the pre-test, in a different order, was administered at the end of the semester.A small number of dummy questions were introduced into both tests, so that participants did not have to answer exactly the same set of questions on both occasions.

Learner Perception Questions

At the end of the interventions, and after the administration of the post-test, learners were asked to complete an anonymous online questionnaire about their experience in the class.They were asked for their view on the utility of the vocabulary learning methods to which they had been exposed, whether they would continue to use the resources they had created after the course, and whether they had acquired any skills other than language through the interventions.There were also some questions about the learning environment which are not immediately relevant to the present study.A qualitative analysis of the findings from the questionnaire is presented in the Results section.

The Interventions

Corpus Construction

In the first three of the 11 weekly classes, the experimental participants created and consulted their own corpora.The corpora were generated from lecture PowerPoints, seminar discussion notes, past test papers (sometimes with answers) and other materials provided by teachers in the AFIB department for students’ use on the course Virtual Learning Environment (VLE, in this case Moodle).Figure 2 shows a typical lecture PowerPoint, which includes learning outcomes, objectives, definitions and explanation of abbreviations, providing a rich set of domain keywords.

Figure 2 Management Accounting lecture slides

As each new week’s lecture slides and seminar notes were made available on Moodle,the students would either add in the new content and grow their corpus, or create a new one.

The procedure for constructing a corpus (and consulting it) is shown in Figure 3.First,the user uploads the text content of teaching materials to form a mini-corpus, using the Sketch Engine: it is possible to upload files in a range of formats, including Word, PDF, zip and text,but PowerPoint files need to be converted to another format first.Because of the nature of lecture slides, the resulting corpus may not contain many full sentences, but it will include the key vocabulary for the particular topic.[[If this paper is accepted, a link to a YouTube explanatory screencast for students will be included here.The video is not anonymous]]

Students could opt to create a very specialized corpus, consisting of perhaps just one or two PowerPoints, for example on “Capital Investment Appraisal” (to which two lectures were devoted).Alternatively they might decide to create a whole-module corpus, such as“Management Accounting”.

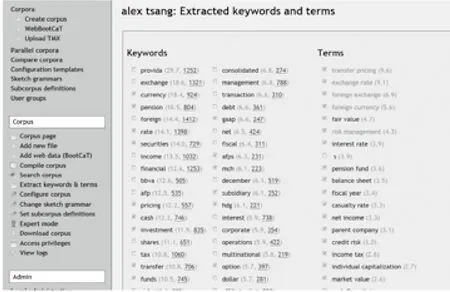

The Sketch Engine software is then used to generate a list of the most salient words—the keywords—in the corpus (words found frequently in the corpus, which are not found in a Sketch Engine defined reference corpus).Thus, the wordtheis not salient, because it is found with equal normalized frequency in both specialist and reference corpora.The BootCat software (Baroni & Bernardini 2004; Baroni et al.2006; available in Sketch Engine,or downloadable from http://bootcat.sslmit.unibo.it/) is then used to bootstrap a much larger corpus, consisting of texts from the web.Figure 3 illustrates this process.

Figure 3 Schematic of corpus construction and consultation.

Key: 1.Text input.2.Wordlist from mini-corpus.3.Bing API interacts with BootCat.4.Word sketch and concordance displays from web corpus.

Construction of the bootstrapped, expanded corpus is seeded with a set of user-supplied keywords: first a search engine module finds web pages that are “about” the keywords, then other BootCat software components extract text from the web pages and generate the corpus,which can then be consulted in various ways.This is one of the most crucial parts of the intervention, since it is here that the learners need to supply the keywords to seed (bootstrap)the expanded corpus.They do this by (1) inspecting the words and terms that Sketch Engine has determined to be salient in the original small corpus, (2) reflecting on whether they are in fact salient to the corpus domain, and (3) checking a box to show this is the case before submitting them to Sketch Engine as seed words.Figure 4 shows a student’s display at the point where he has made his selection and is about to submit.

Figure 4 Student’s Transfer pricing corpus at intermediate stage of construction

Note from Figure 4 that the MWUs are shown separately asterms.In this case, all are two-word terms, but longer MWUs do sometimes emerge as salient.The student has taken the opportunity to ignore spurious items such ass, showing an awareness of the unexpected,characterized by Charles (2012: 97) as “a key feature of corpus work” in construction of a DIY corpus.He has also eliminated words which he considers perhaps not specific enough,such asforeign.Note that a number of on-domain technical abbreviations have also been ticked, such as GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles).

Corpus Consultation

The expanded corpus can be used in the following ways:

1.To produce lists of subject area words and terms for study.

2.To view Word Sketches, which give a one-page view of the collocations and grammatical structures in which a word or term participates.Figure 5 shows the Word Sketch formarket; the reader will note that the most salient collocates areemergein the (incorrectly assigned) object_of relation (emergingmarket),stockas a modifier ofmarket(stock market), andsharein the modified relation (marketshare).Clicking on the underlined frequency statistic yields a concordance for that particular collocation.

Figure 5 A Sketch Engine word sketch, showing principal grammatical relations of a keyword

3.To view a KWIC concordance of the words or terms focused on.Figure 6 shows how a given concordance line centring on a keyword may be selected for expansion.

Figure 6 Sketch Engine concordance output

4.The student may also click on the fileNNNNNNN links seen in the concordance output to refer back to the original texts of which the corpus is composed (from the expanded Web corpus, or from the student’s Moodle corpus).

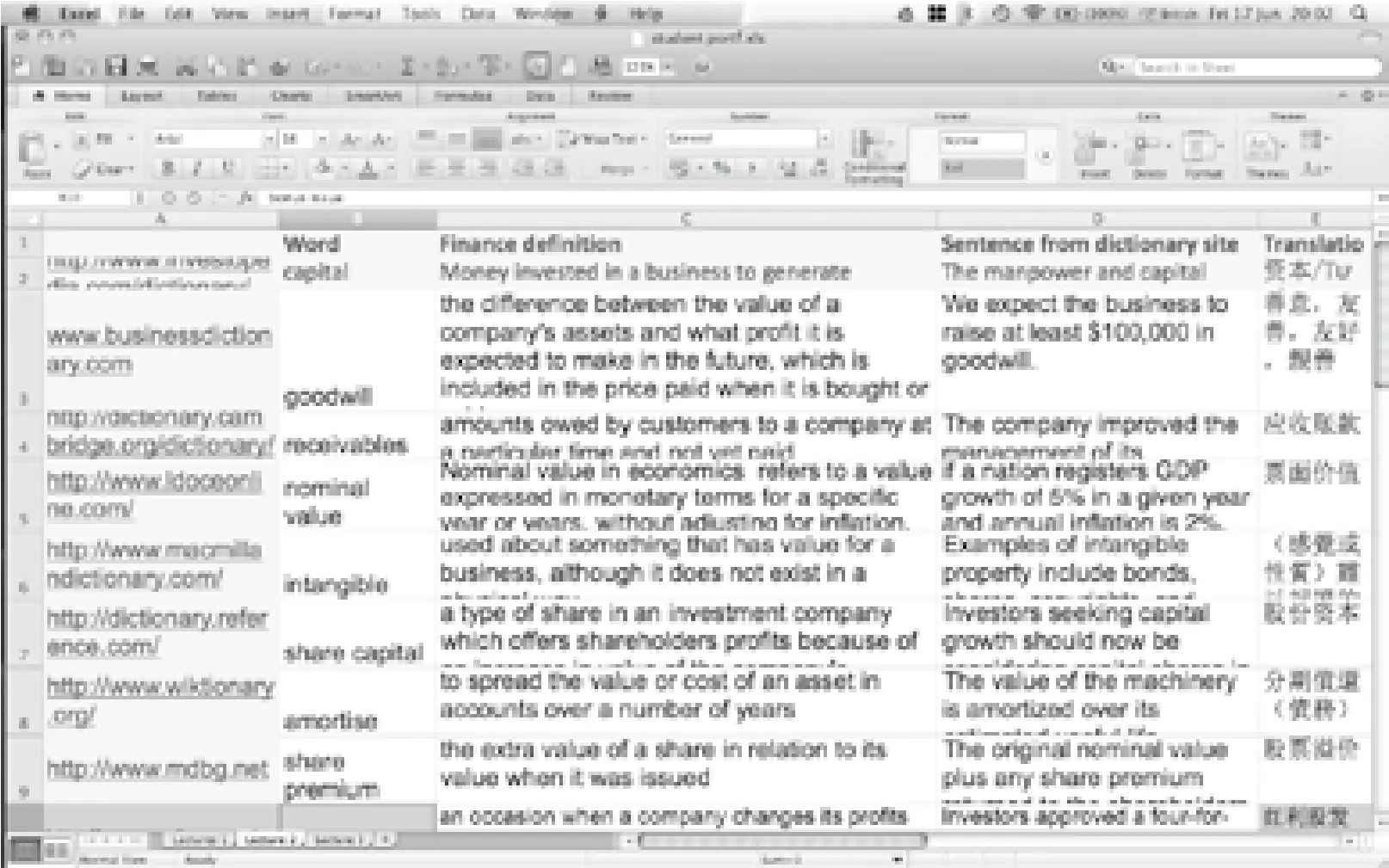

Vocabulary Portfolios

From the fourth week onwards, students were also asked to create and work with personal vocabulary portfolios.The portfolios took the form of an Excel spreadsheet, with a template issued by the instructor, as shown in Figure 7.In the figure, the top two rows (the header row, and the examplecapital), and the leftmost column, consisting of links to dictionaries and other online resources, were supplied by the instructor.These areas of the spreadsheet are grey-shaded in Figure 7.The student has completed the second column with words and terms from their personal management accounting corpus, and the remaining columns with definitions and example sentences from online dictionaries, as well as translations into Chinese, the student’s L1.Students were also encouraged to take example sentences from their personal corpora, although this was less widely taken up.

Figure 7 Student’s vocabulary portfolio excerpt

Control Group Tasks

Three PowerPoint vocabulary quizzes, with gapped KWIC concordances, were developed using domain vocabulary corpora created by the instructor.These were administered using PowerPoint in a similar way to the pre/post-tests, but scores were not recorded.Furthermore,a vocabulary list, generated by the instructor from a corpus containing each week’s ACC or FIN (depending on the group) materials, was placed on Moodle weekly.

RESULTS & DISCUSSION

Of the 94 students enrolled for the modules, 55 were present for both the pre- and posttests: 33 in the two control group classes, and 22 in the experimental group.This rather low response was because of attendance issues at the end of the semester.Lee & S wales (2006)encountered a similar problem in their corpus construction and analysis task, and were eventually led to abandon their planned post-test.I did not take this step, but low sample size is an unfortunate occasional corollary of classroom-based research.In the present study, the numerical improvements in performance that the approach suggests were mostly not found to be statistically significant.

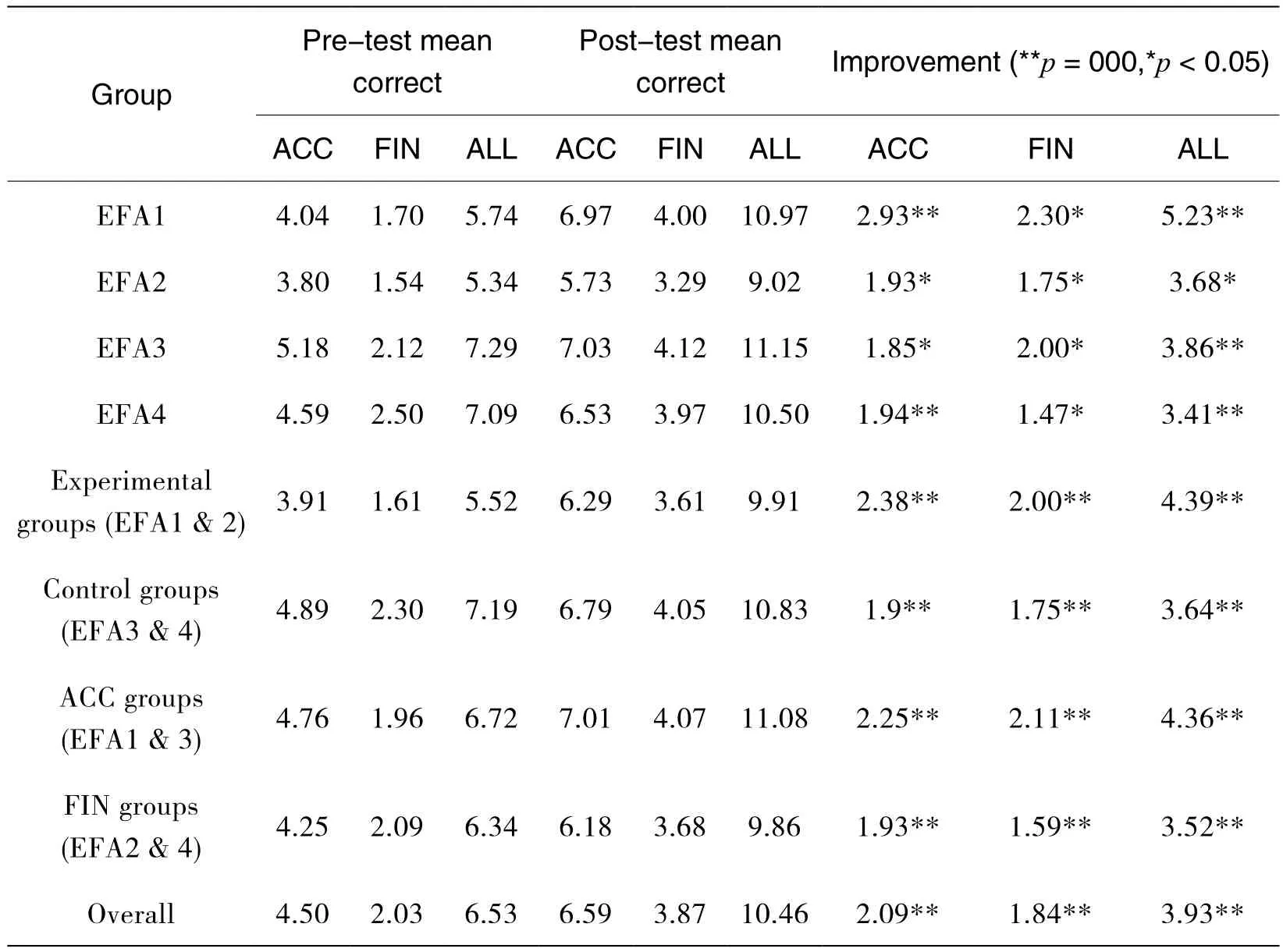

Table 2 Results from pre- and post-tests

Table 2 summarizes the results, giving mean scores in the pre-test and post-test, and the performance improvement (the difference between the pre- and post-test scores).Mean scores are given for each class group (EFA1-4), as well as the combined scores for experimental and control groups, and for the groups focusing on Management Accounting and on International Finance.The columns headed FIN and ACC represent mean scores on International Finance and Management Accounting questions respectively, and ALL is the sum of the two.It will be observed that the scores for FIN questions are lower than those for ACC questions across the board, despite the fact that the FIN scores were adjusted to reflect the lower number of questions; this is probably because the students had been exposed to many of the more general Management Accounting terms in earlier studies, while International Finance, especially with its focus on European markets, was a new field to them.Notwithstanding that, over the period of intervention one would expect roughly equal improvement in scores in both domains, and the improvement scores for FIN and ACC reflect that.

A t-test assuming unequal variance was conducted to measure the improvement on post- over pre-test.All four class groups (EFA1-4) registered post-test scores which were a significant improvement on pre-test scores, as shown in Table 2.Thus, H1 (All groups will perform better in the post-test than they did in the pre-test) was supported.

An unexpected finding was that experimental groups performed less well than control groups on both pre- and post-tests, with the former registering a greater improvement on the post-test.This appears to indicate that the experimental groups consisted of slightly weaker students, and since the groups were assigned arbitrarily there is no immediate explanation.However, these differences were not statistically significant.

A 2-way univariate ANOVA was run in SPSS to compare the pre-post test improvement of various groups, but no differences were found to be significant.Experimental groups saw greater improvement than control groups, so there is some limited support for H2.H3 (that both ACC groups would register greater improvement on ACC items than FIN groups) was partially supported: EFA1 outperformed EFA2, but EFA3 improved less than EFA4.H4 was not supported, as EFA1 and EFA3 both outperformed EFA2 and EFA4 respectively.

For improvement in ACC scores, there was no difference between experiment and control groups for students in the FIN domain.There was a greater improvement for ACC domain students in the experiment group compared to ACC domain students in the control group (improvement of 2.93 compared to 1.85).For improvement in FIN scores, students in both domains saw a greater improvement if they were in the experiment group compared to control (improvement of 2.3 compared to 2.0 for ACC domain; 1.75 compared to 1.47 for FIN domain).Thus, ACC domain students did improve more in ACC scores than they did in FIN scores, and FIN domain students did improve more in FIN scores than they did in ACC scores.Again, the differences were not statistically significant.

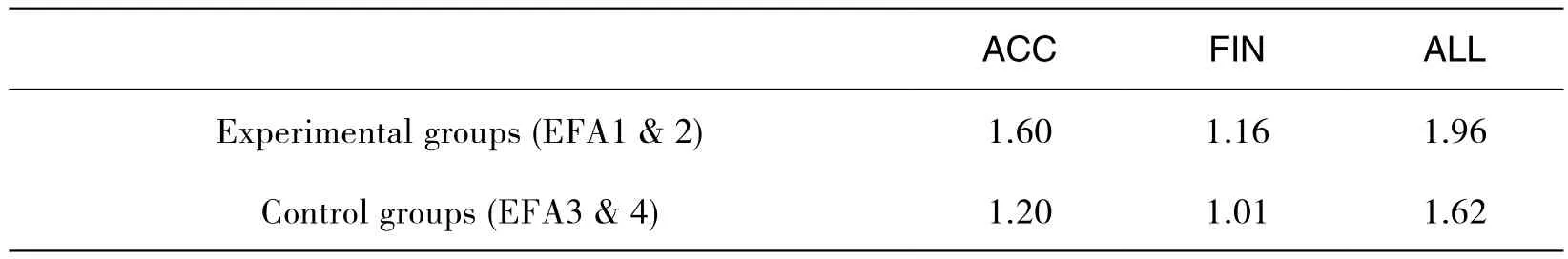

Effect sizes were calculated for the improvement scores of the control and experimental groups, and are shown in Table 3.The figures represent the improvement scores shown in Table 2 divided by the standard deviation in the improvement score for the control group (equal to 1.48 for ACC questions, 1.72 for FIN questions, and 2.24 overall).This way of calculating effect size is described by Coe (2002).

Table 3 Effect sizes for improvement scores of control and experimental groups

The table shows that the effect sizes due to the corpus treatment are indeed larger than those found in the control groups, which used the vocabulary list treatment.For ACC questions to the experimental group, the effect size of 1.6 means that there would be a 79% chance of correctly assigning a random experimental group student to the experimental group, rather than to the control group; that 95% of the control group would have a lower improvement score than the average experimental group score; and that given a control group of 25, only the highest scoring control group member would be likely to attain the average experimental group score.These interpretations are taken from Coe (2002).

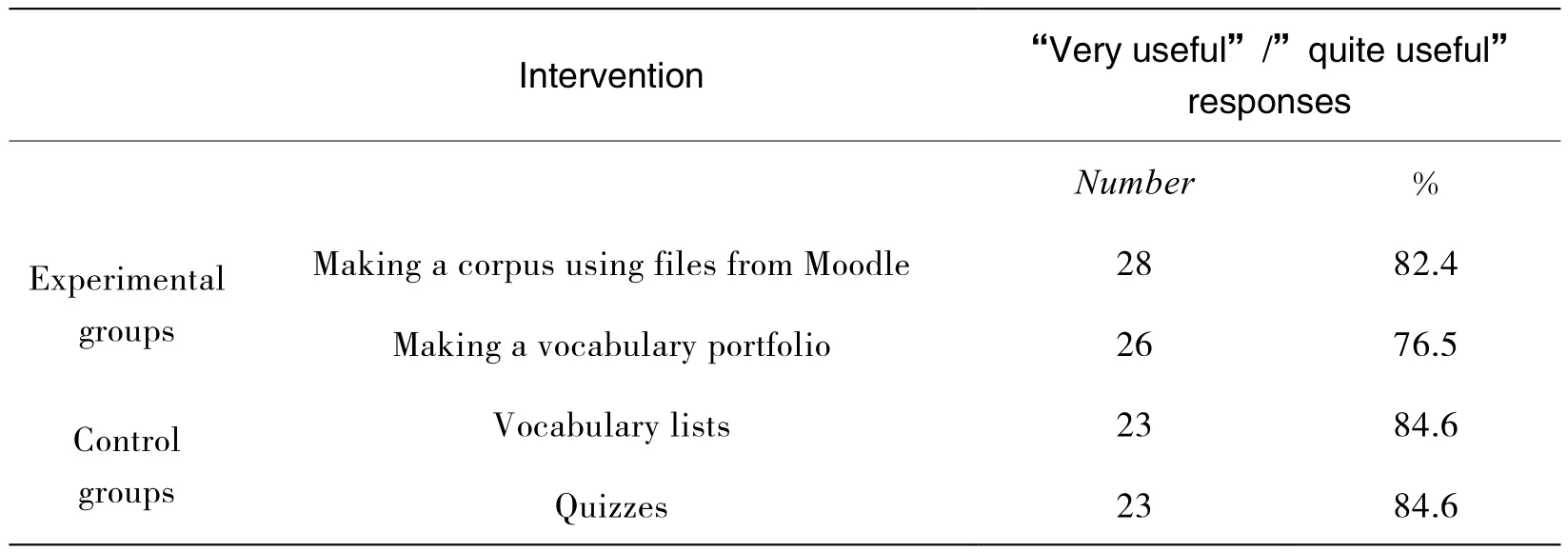

Results from perceptions questionnaire

In all, 60 participants out of 94 completed the post-intervention perceptions questionnaire—34 from the experimental groups and 26 from the control groups.Because the control and experimental groups had been subjected to different teaching approaches, a direct comparison of the success of the methods was not possible.Both experimental and control group respondents appeared to be satisfied with the different aspects of their interventions, as Table 4 illustrates.There are no significant differences between the responses.

Table 4 Level of participant satisfaction with interventions

When asked whether they would continue to use the corpus and vocabulary portfolio resources after the end of the course, 20 respondents (58.8%) claimed that they would, while 6 (17.6%) stated that they would like to but were not sure how.All learners felt that they had acquired non-language/transferable skills, with 28 learners (70%) citing programs such as Office and Sketch Engine as the most significant, and the other 12 (30%) stating that their Web search skills had improved.

For the experimental group students, it seems to be in the construction of the corpus and the compilation of the vocabulary portfolio that the benefit of the approach lies.The Sketch Engine platform offers a number of tools for inspecting the data, and the students found the Word Sketch function of particular interest.Anecdotally, they appeared to have less patience to deal with concordance output, and it was somewhat difficult to convince them of the pedagogical value of examining sentence fragments; the reservations of Kilgarriff (2008),Lamy & Klarskov Mortensen (2007), and Yoon and Hirvela (2004), noted in the Literature Review, probably apply to the participants of this study as well.

LIMITATIONS

As has been noted already, the limited sample size (occasioned partly by the relatively low number of participants in the post-test) and consequent lack of statistically significant improvement figures means that the results from the study, while promising, must be seen as tentative.

There is, of course, rather more to “knowing” a word or term than being able to match it to a definition or use it in a gap-fill, so it is not known how valid the pre- and post-test were as a means of measuring vocabulary knowledge: they might not capture the extent to which students benefited from the intervention, and it may be that the benefits of this type of activity are not readily tangible or measurable by tests.

A limitation of the questionnaire feedback should be noted: even though responses were anonymous, it is still likely that some of the students would have responded positively because they felt it was the right thing to do.

There were also some logistical difficulties with the approach.For one, it was quite difficult to schedule the vocabulary tasks with a crowded EAP syllabus to cover, in a class which only met for two hours per week.This meant that I was not able to spend as much time on the interventions as I would have liked.The process of logging in and finding the corpora or files that were being worked on the previous week tended to eat into class time, and students needed constant monitoring to keep them on task and away from online distractions.

Some tasks were assigned for self-study in the early part of the semester, with students being asked to feed back to the class by way of Moodle forums.With this particular cohort of students, however, other coursework commitments (and perhaps motivational factors) meant that students were happier working on tasks in the classroom.The presence of a facilitating teacher probably also provided reassurance for them.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PLANS

This paper has presented a DIY corpus construction and vocabulary portfolio compilation intervention for university students of academic English who major in Accounting & Finance.Improvements in technical vocabulary knowledge, it is tentatively concluded, were made as a result of the intervention, and students reported that the experience was beneficial.Encouraging effect sizes of the intervention were also found.

Improvements were mostly not, however, found to be statistically significant.For this,larger numbers are needed; fortunately, our inter-departmental collaborations mean that in future cohorts, it will be possible to repeat the experiment on a larger scale.EAP students in other disciplines (for example International Business, and Engineering) will be encouraged to create corpora and vocabulary portfolios as part of their Academic English modules.In our university context, this will bring the added benefit of extending the demographics of the study: virtually all AFIB students at our institution are from China, and it would be interesting to see whether the findings can be generalized to other cultural/L2 backgrounds (since other cohorts are more mixed in terms of nationalities).

Although the organizational and logistical aspects were not formally evaluated, I believe that the challenges met with by the teacher were to some extent offset by benefits to the students, who had previously had very little experience of file management or any kind of professional/academic use of computer resources (other than word processing and web searches).Jackson (1997) lists a number of such skills that his Computer Aided Text Analysis students acquired: project management, problem solving and report writing, as well as computer skills.The questionnaire results of the present study, indeed, suggest that useful transferable skills were acquired, and this is something that ought to be further explored in a future study.

Traditionally, quite a lot of CALL provision intended for lab use has consisted of gapfill or drop-down menu tasks.Students tend to find these quite fun, but they may be of greater utility for mastering (say) the mechanics of paraphrasing, or the niceties of a particular tense,than discovery of relevant, domain-specific, authentic vocabulary in context.The corpusinformed lexical resource creation tasks described here provide a motivating and meaningful way for students to access and learn the terminology and usages of their own specialist subjects.