Timing, distribution, and microbiology of infectious complications after necrotizing pancreatitis

2019-09-25JiongDiLuFengCaoYiXuanDingYuDuoWuYuLinGuoFeiLi

Jiong-Di Lu, Feng Cao, Yi-Xuan Ding, Yu-Duo Wu, Yu-Lin Guo, Fei Li

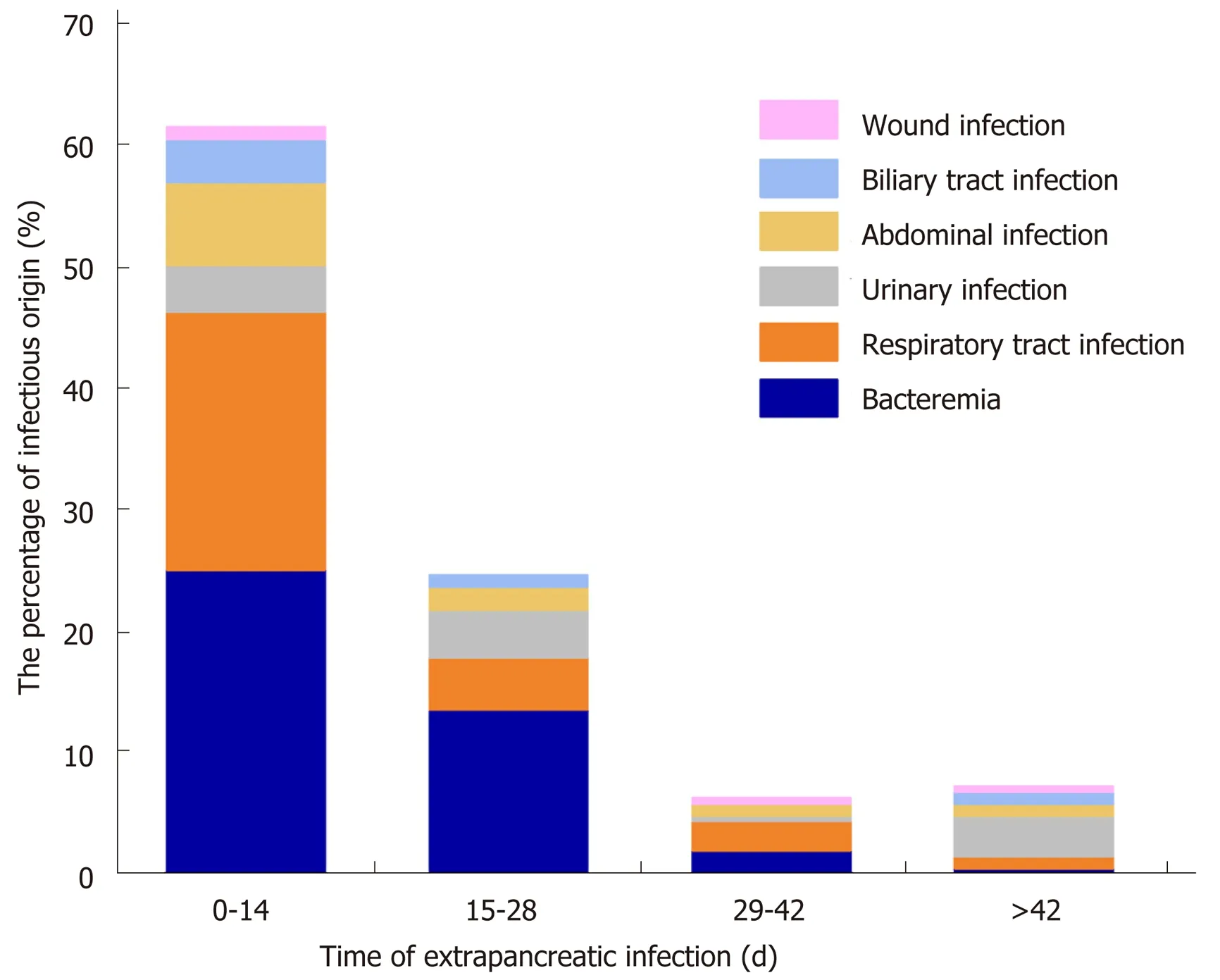

Abstract BACKGROUND Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common acute abdominal disease worldwide, and its incidence rate has increased annually. Approximately 20% of AP patients develop into necrotizing pancreatitis (NP), and 40% to 70% of NP patients have infectious complications, which usually indicate a worse prognosis. Infection is an important sign of complications in NP patients.AIM To investigate the difference in infection time, infection site, and infectious strain in NP patients with infectious complications.METHODS The clinical data of AP patients visiting the Department of General Surgery of Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2018 were collected retrospectively. Enhanced computerized tomography or magnetic resonance imaging findings in patients with NP were included in the study. Statistical analysis of infectious bacteria, infection site, and infection time in NP patients with infectious complications was performed,because knowledge about pathogens and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns is essential for selecting an appropriate antibiotic. In addition, the factors that might influence the prognosis of patients were analyzed.RESULTS In this study, 539 strains of pathogenic bacteria were isolated from 162 patients with NP infection, including 212 strains from pancreatic infections and 327 strains from extrapancreatic infections. Gram-negative bacteria were the main infectious species, the most common of which were Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The extrapancreatic infection time (9.1 ± 8.8 d) was earlier than the pancreatic infection time (13.9 ± 12.3 d). Among NP patients with early extrapancreatic infection (< 14 d), bacteremia (25.12%) and respiratory tract infection (21.26%) were predominant. Among NP patients with late extrapancreatic infection (> 14 d), bacteremia (15.94%), respiratory tract infection(7.74%), and urinary tract infection (7.71%) were predominant. Drug sensitivity analysis showed that P. aeruginosa was sensitive to enzymatic penicillins, thirdand fourth-generation cephalosporins, and carbapenems. Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae were sensitive only to tigecycline; Staphylococcus epidermidis and Enterococcus faecium were highly sensitive to linezolid, tigecycline,and vancomycin.CONCLUSION In this study, we identified the timing, the common species, and site of infection in patients with NP.

Key words: Necrotizing pancreatitis; Extrapancreatic infection; Pathogenic bacteria; Drug sensitivity test

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common acute abdominal disease worldwide, and its incidence rate has increased annually[1]. With the progression of the disease, 20% of AP patients develop into necrotizing pancreatitis (NP). Approximately 40% to 70% of NP patients have infectious complications, which usually indicate a worse prognosis.Infection is an important sign of complications in NP patients[1-5]. To date, studies on pancreatic infection have mainly focused on pancreatic and peripancreatic infection,but few have focused on extrapancreatic infection and coinfection.

Therefore, this study collected clinical data of NP patients who visited our hospital from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2018. The aim was to analyze the difference in infection time, infection site, and bacterial strains in NP patients with infectious complications and the influence of these factors on mortality, in order to help determine treatment strategies for NP patients with coinfection.

MATERIALSANDMETHODS

Patients

The clinical data of NP patients who visited our hospital from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2018 were retrospectively collected.

Inclusion criteria

Patients diagnosed with NP by enhanced computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were: (1) Acute attack of chronic pancreatitis; (2) Abdominal exploratory surgery due to pancreatitis; (3) Pancreatitis due to abdominal surgery;and (4) Acute abdominal events such as visceral organ perforation, bleeding, and abdominal compartment syndrome

Definitions

AP:AP can be diagnosed by any two of the following three items: (1) Acute epigastric pain, radiating to the waist and back; (2) Blood amylase and/or lipase levels at least three times higher than the normal limit; and (3) The presence of typical pancreatic lesions upon imaging examination (such as abdominal ultrasound, enhanced CT, or MRI).

NP:NP presents inflammation associated with pancreatic parenchymal necrosis and/or peripancreatic necrosis. On contrast-enhanced CT, there is lack of pancreatic parenchymal enhancement by intravenous contrast agent and/or the presence of findings of peripancreatic necrosis[3]. According to Balthazaret al[6], the degree of pancreatic necrosis in NP patients is classified as < 30%, 30%-50%, and > 50%.

Infectious NP (INP):In clinical treatment, pancreatic infection is suspected in NP patients when one of the following symptoms is present: (1) Sudden high fever (> 38.5°C) or persistent fever (> 38.5 °C) that does not return; (2) A significant increase in leukocyte count, or the percentage of neutrophils and inflammatory markers (CRP,IL-6, and PCT); and (3) Continuous deterioration of clinical symptoms such as newonset organ failure or multiple organ failure. Diagnostic methods include the following: (1) Enhanced CT showing gas configurations in the necrotic collection; and(2) Positive culture from pancreatic necrosis obtained by puncture or operation.

Extrapancreatic infection:Extrapancreatic infection is defined as infection occurring in other organs of AP patients. Common sites of extrapancreatic infection include the blood, respiratory tract, urinary tract, abdominal cavity, biliary tract, and surgical incision site[7-9]. When infection symptoms are suspected in AP patients, but no definite signs of infection (bubbles) are found in the necrotic pancreatic tissue on imaging, and the culture of necrotic tissue and pus from puncture and drainage is negative, suspected patients with extrapancreatic infection can be diagnosed or excluded by multiple, multisite pathogen culture[4,5,7-9].

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria:MDR bacteria, which are bacteria that are usually sensitive to three or more commonly used antibiotics but show simultaneous resistance to these drugs, were evaluated according to the Chinese expert consensus on the prevention and control of nosocomial infection by MDR bacteria.

Management of patients

After admission, patients with confirmed NP were treated conservatively with analgesics, fluid resuscitation, and supportive treatment. Patients with clinically severe AP (suspected or confirmed symptoms of organ failure) were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with all possible organ support systems, including ventilatory support, vasopressors, and dialysis as and when required. Patients with sterile necrosis are usually treated conservatively. For NP patients with suspected or confirmed infectious complications, broad-spectrum antibiotics (such as third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins and carbapenems) were used to control infection,and sensitive antibiotics were selected according to the drug sensitivity results of the patients. The indications for surgical intervention in NP patients were as follows: (1)After conservative treatment, the clinical symptoms did not improve significantly or worsened continuously; (2) Pancreatic infection was confirmed in the patient; and (3)The range of sterile necrosis in the patient was enlarged, and the surrounding organs were compressed. Minimally invasive approaches to remove necrotic tissue are usually selected according to the necrotic site in the patient.

Statistical analysis

Data were input into Excel 2018, the baseline data are recorded as the mean ± SD or medians (ranges) as appropriate. Independent samplest-tests were performed to analyze the differences between the groups. Qualitative data were scored, and chisquare or Fisher’s exact tests were performed to analyze the differences between the groups. Logistic regression was used to determine the risk of death in the patientsviaSPSS 23.0 statistical software, with the level of statistical significance set asP< 0.05.

RESULTS

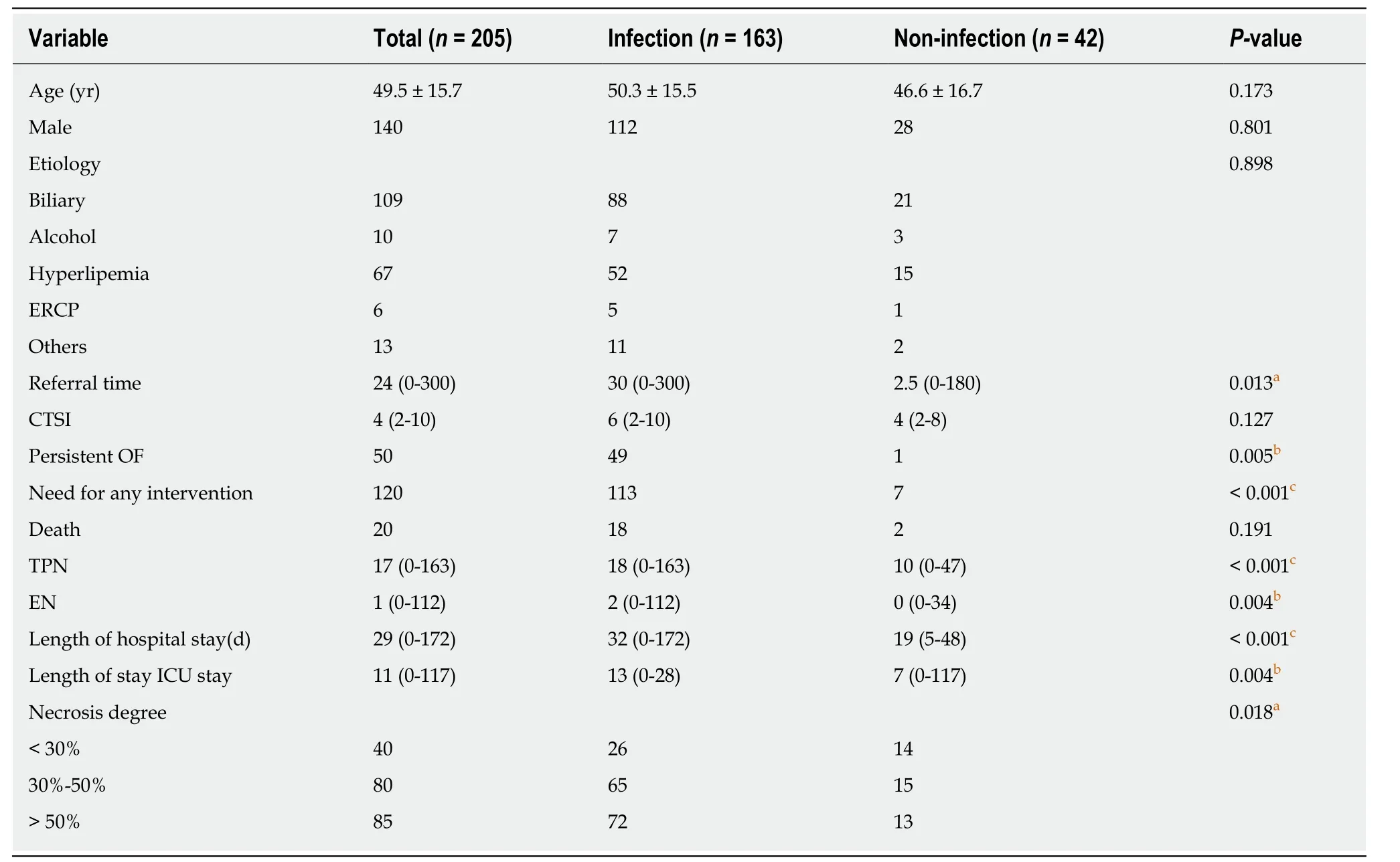

We collected the clinical data of patients with AP who visited our department from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2018. A total of 205 NP patients were enrolled according to the results of enhanced CT in our hospital or another hospital. There were 140 males and 65 females, with an average age of 49.5 ± 15.7 years. The causes of NP were gallstones in 109 patients, hyperlipidemia in 67 patients, unknown etiology in 12 patients, alcoholism in 10 patients, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in 6 patients, and posttraumatic pancreatitis in 1 patient. There was no significant difference in age, sex, or etiology between the infection group and the non-infection group (Table 1).

Among the 205 NP patients, 163 had infectious complications, and 42 had sterile necrosis. The different degrees of pancreatic necrosis in the patients with NP were as follows: 40 (26/14) patients with less than 30% necrosis, 80 (65/15) with 30%-50%necrosis, and 85 (72/13) with more than 50% necrosis. The median modified computer tomography severity scan (CTSI) score was 4 (range, 0-10). There was a significant difference in the degree of necrosis between the infection group and the non-infection group (Table 1).

Among the 205 NP patients, 179 were referred, with a median referral time of 24 d;150 had infectious complications and 29 had aseptic NP. There was no significant difference in the referral time between the infection group and the non-infection group (Table 1).

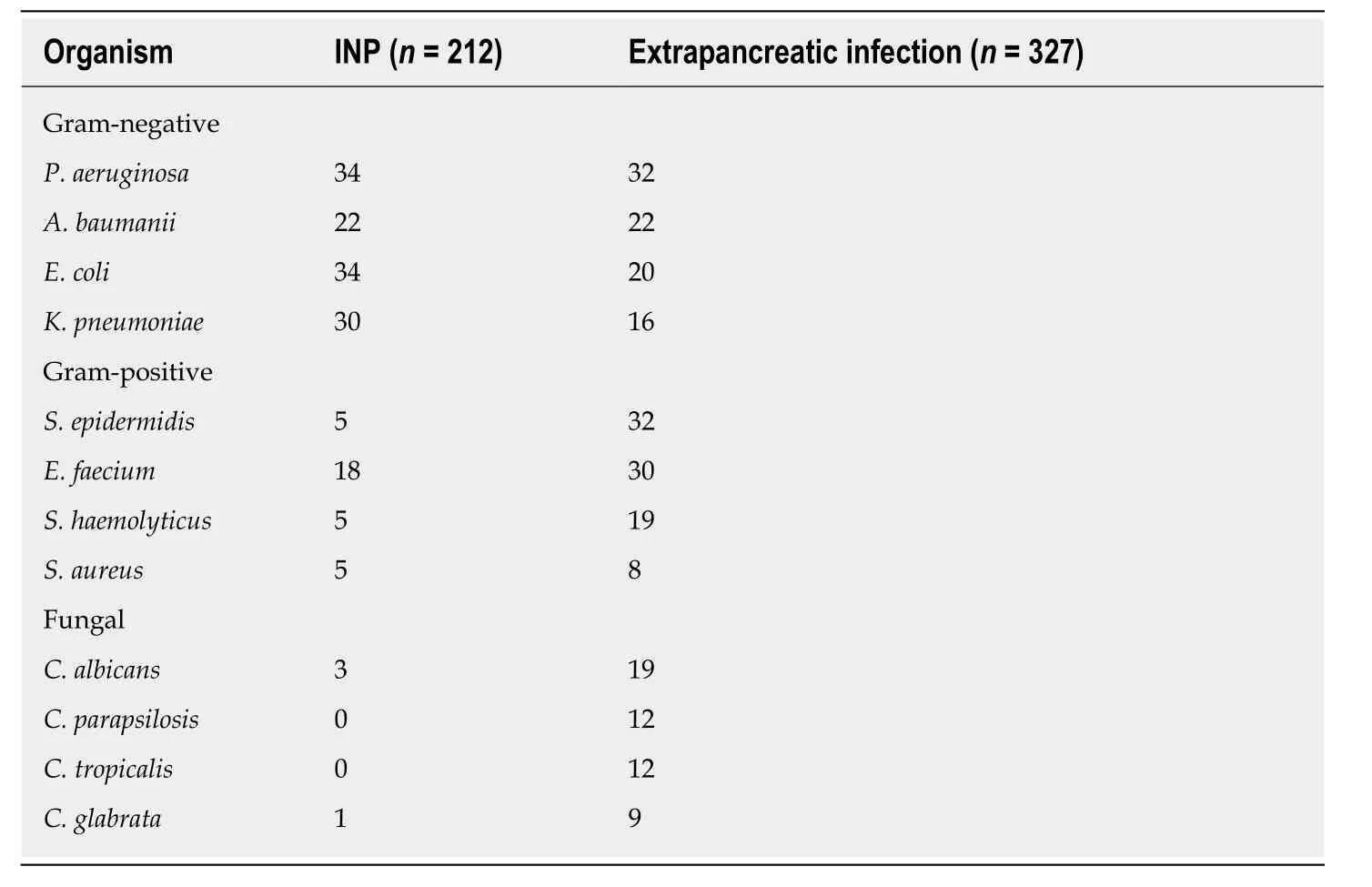

Spectrum of pathogenic bacteria in infected patients

Among the 162 NP patients with confirmed infectious complications, 539 strains of pathogenic bacteria were isolated, of which 21 were cultured from 112 patients with pancreatic infection. The most common Gram-negative bacteria wereP. aeruginosaandE. coli(n= 34). The most common Gram-positive bacterial species wasEnterococcus faecium(n= 18), and the most common fungus wasCandida albicans(n=3). A total of 327 strains were cultured from 132 patients with extrapancreatic infection, including 165 strains from blood, 77 from the respiratory tract, 35 from the urinary tract, 25 from the abdominal cavity, 20 from the biliary tract, and 5 from wound infections. The most common Gram-negative bacterial species wasP.aeruginosa(n= 32), the most common Gram-positive bacterial species wasStaphylococcus epidermidis(n= 32), and the most common fungus wasC. albicans(n=19). Fungal infection was found in 39 patients; 4 strains of pathogenic fungi were cultured from three patients with pancreatic infections, and 52 strains of pathogenic fungi were cultured from 36 patients with extrapancreatic infections (24 from blood, 5 from the respiratory tract, and 17 from the urinary system) (Table 2).

Drug sensitivity analysis of pathogens in infected patients

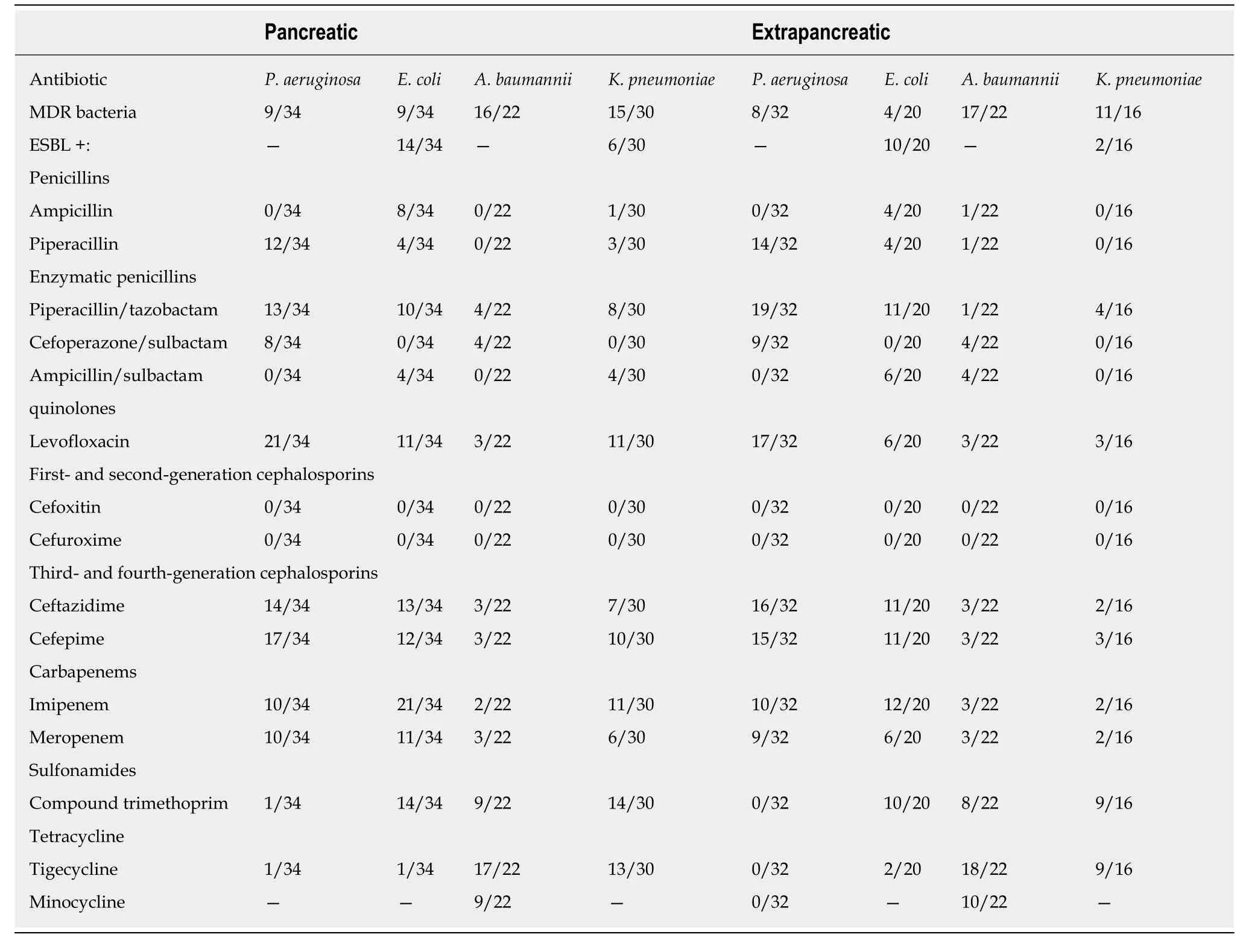

Gram-negative bacteria:Almost all gram-negative bacteria cultured from cases of INP were resistant to first- and second-generation cephalosporins and nonenzymatic penicillin. The most commonE. coliwas sensitive to carbapenems and to third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins.Klebsiella pneumoniaewas generally resistant to commonly used antibiotics, and the resistance rate to carbapenems was more than 50%.P. aeruginosawas more sensitive to third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins than to other antibiotic classes. The percentages ofE. coliandK. pneumoniaestrains producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) were 41.18% (14/34) and 20%(6/30), respectively. The drug sensitivity of Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria in NP cases with extrapancreatic infection was low.A. baumanniiandK. pneumoniaewere the most sensitive of the identified species to tigecycline.E. coliandP. aeruginosawere still susceptible to cephalosporins and carbapenems (approximately 50%). The percentages of ESBL-positiveE. coliandK. pneumoniaestrains were both 50% (10/20)(Table 3).

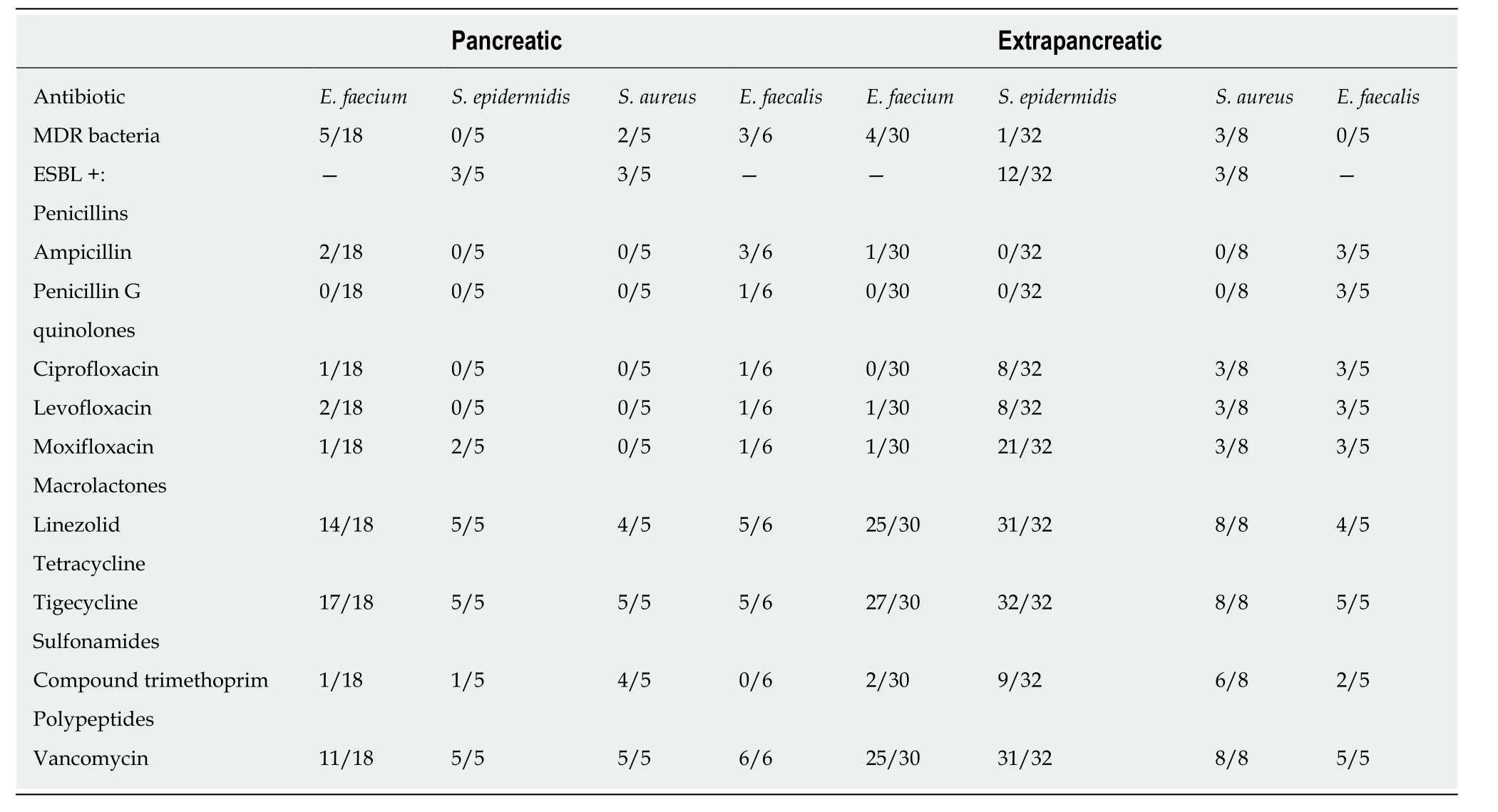

Gram-positive bacteria:Gram-positive bacteria in INP patients were sensitive to vancomycin and tigecycline, but resistant to other antibiotics. The most commonE.faeciumwas highly susceptible to macrolides (77.78%, 14/18).Staphylococcus aureuswas almost 100% sensitive to quinolones, tetracyclines, penicillins, aminoglycosides,and sulfonamide compounds. The percentages of ESBL-positiveS. epidermidisandS.aureusstrains were 60% (3/5) and 60% (3/5), respectively. The drug sensitivities of Gram-positive pathogens in NP with extrapancreatic infection were slightly different.Most of these organisms were highly sensitive to macrolides, tetracyclines, and polypeptide antibiotics (> 80%). ESBL producing strains ofS. epidermidisandS. aureusaccounted for 37% (12/32) and 37.5% (3/8) of the strains, respectively (Table 4).

Fungal infection:According to the drug sensitivity of NP patients,C. albicanswas the main pathogenic fungus cultured in patients with either pancreatic or extrapancreaticinfection.C. albicanswas sensitive to the antifungal drugs currently used in the clinic,such as 5-fluorocytosine, amphotericin B, and fluconazole.

Table 1 Comparison of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics between the infection group and non-infection group

MDR bacteria:Among the common Gram-negative bacilli identified in INP cases, the rates of multidrug resistance were as follows:P. aeruginosa, 26.47% (9/34);K.pneumoniae, 50% (15/30);E. coli, 26.47% (9/34); andA. baumannii, 72.73% (16/22). The multidrug resistance rate of common Gram-positive cocci was as follows:E. faecium,27.78% (5/18). The multidrug resistance rates of common gram-negative bacteria in extrapancreatic infections were as follows:P. aeruginosa, 25% (8/32);K. pneumoniae,68.75% (11/16);E. coli, 20% (4/20); andA. baumannii, 77.27% (17/22). The multidrug resistance rates of common gram-positive bacteria were as follows:S. epidermidis,3.13% (1/32) andE. faecium, 13.33% (4/30).

Infection time and location

In this study, the extrapancreatic infection time was 9.1 ± 8.8 d, the pancreatic infection time was 13.9 ± 12.3 d, and the fungal infection time was (31.6 ± 26.4 d,P<0.05). Among the 132 NP patients with extrapancreatic infection, 85 had bacteremia,60 had respiratory tract infection, 25 had urinary tract infection, 22 had abdominal infection, 11 had biliary tract infection, and 4 had wound infection. The common sites of extrapancreatic infection in patients with early NP (< 14 d) were the blood and respiratory tract. The common sites of extrapancreatic infection in patients with advanced NP (> 14 d) were the blood, respiratory tract, and urinary tract (Figure 1).

Prognosis of NP patients

In this study, among the 42 cases of sterile NP, 35 were treated conservatively, and 7 were treated surgically. Six patients underwent intracystic drainage or video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD) to remove necrotic tissue. One patient was treated by interventional embolization for arterial hemorrhage. Among the 163 patients with infection, 50 received only symptomatic supportive treatment such as anti-inflammatory therapy, and 113 patients with NP underwent surgical treatment.Seven patients received only percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) and antiinflammatory treatment, while the remaining 106 patients received VARD and anti-inflammatory treatment. Postoperative complications occurred in 21 patients:bleeding in 10, interventional therapy in 3 (hepatic artery in 1 and splenic artery in 2),digestive tract fistula in 8, and pancreatic fistula in 3.

Table 2 Microbiological profile of organisms in infected patients

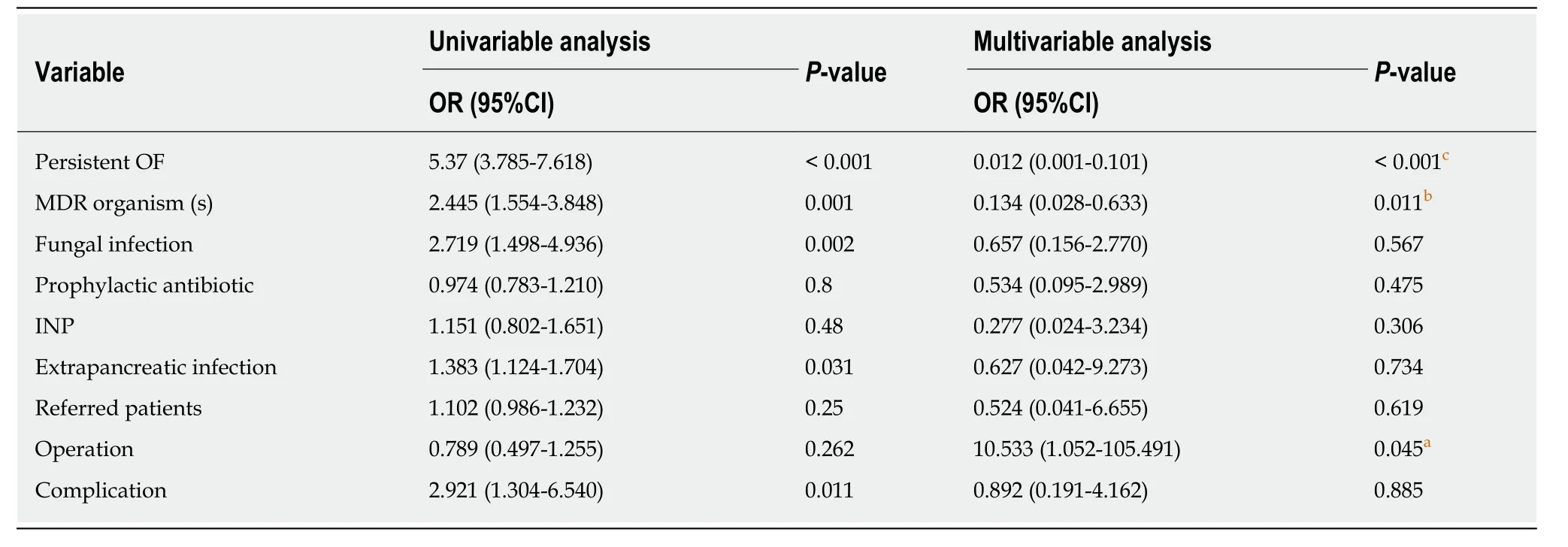

In this study, the overall mortality rate was approximately 9.76% (n= 20). Of the 42 patients with sterile necrosis, 7 treated surgically were discharged from the hospital,and 2 treated conservatively died. Of the 163 NP patients with infectious complications, 7 died of infectious necrosis treated conservatively, and 2 died of PCD only. Nine patients died after VARD treatment. A total of 50 patients suffered from organ failure, including 1 in the noninfection group and 49 in the infection group. A total of 18 patients died, with a mortality rate of 36%. Regression analysis showed that the mortality rate was related to persistent organ failure, infection with multiple drugresistant bacteria, and the number of operations (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Many guidelines and studies suggest that infection is a risk factor for late mortality in NP patients and an indication for surgery[1-3,7-10]. Currently, the concept of surgery for INP patients has changed from "early, multiple, open debridement" to "delayed,drainage, minimally invasive". The superiority of the “step-up” approach to “open necrosectomy” for NP has been widely recognized[11-15]. Our center delays the progression of NP patients with suspected or confirmed infection by timely conservative treatment such as analgesia, fluid resuscitation, anti-inflammatory agents, and enteral (parenteral) nutrition. In a large number of clinical practices, we believe that the choice of antibiotic treatment for NP patients with infection, especially before the results of the first bacterial culture are obtained, is still relatively blind.

In our study, cultures of pathogenic bacteria from infected NP patients were analyzed. Gram-negative bacteria were the main pathogens in pancreatic and extrapancreatic infections.E. coliandK. pneumoniaewere the most common pathogens in pancreatic infections, consistent with the findings in most studies on infectious pathogens[7,8,10,16-21]. Immune suppression in early NP patients may lead to excessive systemic inflammatory response syndrome, which increases intestinal mucosal permeability and damages intestinal commensal microorganisms, resulting in translocation of the intestinal flora and pancreatic infection. The main pathogenic bacteria in extrapancreatic infections were different from those in pancreatic infections.P. aeruginosaandA. baumanniiwere the most common Gram-negative bacteria in extrapancreatic infection.E. coliandK. pneum oniaewere the main Gramnegative bacteria in pancreatic infections. The bacteria in pancreatic infections mayoriginate primarily from the intestinal tract; thus, intestinal bacteria are common,while the bacteria in extrapancreatic infections differ by infection site.

Table 3 Drug sensitivity of Gram-negative bacteria in infected patients

According to the analysis of extrapancreatic infection time in NP patients, the extrapancreatic infection time was earlier than the pancreatic infection time,consistent with the conclusions of other studies[4,5,7,8]. In both early (< 14 d) and late (>42 d) infections, bacteremia is a common source of infection. In the early stage,bacteremia may occur due to the suppression of immune function by a systemic inflammatory reaction, which may affect the prognosis of NP patients[5]. Brownet al[4]noted that the most common manifestations of extrapancreatic infections in severe AP patients were respiratory tract infections (9.2%) and bacteremia (8.4%). Mokaet al[8]noted that INP patients with extrapancreatic infection (pneumonia or bacteremia) had significantly higher total hospitalization lengths, ICU hospitalization lengths, and mortality rates than those without extrapancreatic infection. In a retrospective study by Besselinket al[10], bacteremia was considered an independent risk factor for predicting death in AP patients, and increased the risk of pancreatic parenchymal necrosis and infection. The predominance of bacteremia in late extrapancreatic infections may be related to long hospitalization times, multiple operations,secondary iatrogenic infections, or prolonged indwelling times of deep venous catheters and catheters for long-term parenteral nutrition[22].

In this study, the multidrug resistance rate of common Gram-negative bacteria (K.pneumoniae,P. aeruginosa,E. coli, andA. baumannii) found in INP in our center ranged from 23.68% to 72.73%. The multidrug resistance rate of common Gram-positive bacteria (E. faecium) was 27.78%. The multidrug resistance rates of common Gramnegative bacteria (K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, andA. baumannii) in extrapancreatic infections ranged from 25% to 81.82%. The multidrug resistance rate of common G ram-positive bacteria (E. faecium) was 20%. Mouradet al[21]have also reported that prolonged antibiotic use leads to MDR bacterial and fungal infections,which are also associated with prolonged hospitalization and poor prognosis.Therefore, it is necessary to replace antibiotics to which pathogens are sensitive or discontinue drugs in a timely manner, according to the patient's condition, to reduce the risk of the bacteria developing multidrug resistance. In this study, 39 patients developed fungal infections and 56 strains of pathogenic fungi were cultured. The most common pathogenic fungus wasC. albicans. Notably, the 39 cases of fungal infection were all mixed infections, and the occurrence time of fungal infections was later than that of bacterial infections. This difference may be related to the long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the decline of autoimmunity in NP patients.Most studies consider fungal infection a risk factor for mortality in infected patients[7,8,10,19,23-25]. However, whether antifungal drugs should be used prophylactically in patients with suspected or confirmed extrapancreatic (and) or pancreatic infections requiring antibiotics remains controversial. The preventive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics or antifungal therapy may increase the incidence of bacterial or fungal superinfection[8,19]. The preventive use of antibiotics has not increased the incidence of fungal infections and may reduce the incidence of fungal infections in patients, but further large-scale studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis[23,24]. In this study, the degree of pancreatic necrosis, CTSI score, rate of referral, rate of organ failure, need for surgical intervention, need for enteral nutrition,need for parenteral nutrition, and length of hospitalization were higher in NP patients in the infection group than in NP patients in the non-infection group. In the infection group, most patients (n= 150) were referred from an outside hospital. Their basic vital signs and immune function were poor at admission, and the incidence of adverse events such as organ failure and aggravation of pancreatic necrosis increased with prolonged disease course. Long-term nutritional support and even surgery were needed, which prolonged the hospitalization time of the patients. In addition, many studies support the view that the risk of pancreatic infection increases with the degree of pancreatic necrosis[1-3,11-16]. However, in this study, the infection rate of NP patients with simple extrapancreatic infection was also higher than that of the non-infection group, which may be related to the poor autoimmunity and severe inflammation in patients with extrapancreatic infection. In addition, false negative results for the culture of pathogenic bacteria from the pancreas in some patients with simple extrapancreatic infection were not excluded.

Table 4 Drug sensitivity of Gram-positive bacteria in infected patients

In addition, some issues need to be addressed. First, most patients were treated with antibiotics before surgery, and the related effects need to be further analyzed.Second, a few patients were diagnosed with INP during outpatient treatment, but there was no detailed record of the infectious strains, and there was a certain deviation in the number of pathogenic bacteria. Third, the changes in pathogenic bacteria before and after surgery were not analyzed. Finally, the difference between pancreatic necrosis and peri-pancreatic necrosis was not mentioned.

Figure 1 Time and location distribution of extrapancreatic infection. In the early stage of necrotizing pancreatitis(NP), the most common sites of extrapancreatic infection were the blood, respiratory tract, and abdominal cavity. In the late stage of NP, the most common sites of extrapancreatic infection were the blood, respiratory tract, and urinary tract. NP: Necrotizing pancreatitis.

In conclusion, when NP patients present clinical symptoms of suspected infection,such as fever, elevated inflammatory indexes, and sepsis, but no clear indication of pancreatic infection revealed by enhanced CT examination, the culture from site of extrapancreatic infection can be given priority (different extrapancreatic culture sites can be selected according to the onset time). If no extrapancreatic infection was diagnosed, surgical procedures should be considered to determine whether the patient has pancreatic infection. In addition, our study has shown that although Gram-negative bacteria are still dominant in NP patients, MDR bacterial infection tends to increase. Therefore, anti-infection treatment should be carried out after it is clear that the patient has symptoms of infection. For NP patients with confirmed infection, priority can be given to antibiotics to which Gram-negative bacteria are sensitive, and then sensitive antibiotics can be selected according to the results of drug sensitivity. When NP patients are clearly complicated with infection symptoms, they should be paid close attention to the risk of organ failure, MDR bacterial infection, or multiple operations. Hence, understanding the pathogen spectrum and drug sensitivity testing of NP patients with infectious symptoms will help clinicians to use antibiotics effectively and reasonably, improve the therapeutic effect, and reduce the related mortality of NP patients.

Table 5 Multivariable analysis for independent predictors of mortality

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

As acute pancreatitis patients progress to necrotizing pancreatitis (NP), their hospitalization costs and mortality rates become much higher than those of patients with edematous pancreatitis. Approximately 40%-70% of NP cases present with symptoms of infection, and infection has become the most important risk factor for death from NP. Therefore, it is critical to identify patients with NP who have symptoms of infection.

Research motivation

Studies on pancreatic infectioushave mainly focused on pancreatic and peripancreatic infections,and little is known about extrapancreatic infections and coinfections. We considered the difference in infection time, infection site, and infectious strains in NP patients with infectious complications, and found that early intervention may decrease the mortality rate.

Research objectives

Infectious NP, extrapancreatic infection, and coinfection are the common complications of NP.The research is critical to improve the treatment strategy for NP patients with infectious complications.

Research methods

This study included 205 patients with NP. The baseline data were recorded as the mean ± SD or medians (ranges) as appropriate. Independent samplest-tests were performed to analyze the differences between the groups. Qualitative data were scored, and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were performed to analyze the differences between the groups. Logistic regression was used to determine the risk of death in the patients usingviaSPSS 23.0 statistical software.

Research results

A total of 539 strains of pathogenic bacteria were cultured from the 162 NP patients with confirmed infectious complications. The most common Gram-negative bacteria wereP.aeruginosaandE. coli(n= 34). The most common Gram-positive bacteria wereE. faecium(n= 18),and the most common fungus wasC. albicans(n= 3). The extrapancreatic infection time was 9.1 ±8.8 d, the pancreatic infection time was 13.9 ± 12.3 d, and the fungal infection time was 31.6 ± 26.4 d (P< 0.05). The common sites of extrapancreatic infection in patients with advanced NP (> 14 d)were the blood, respiratory tract, and urinary tract.

Research conclusions

This retrospective analysis of NP patients with infectious com-plications in our hospital shows that the main pathogenic bacteria in NP patients were Gram-negative bacteria, the most common of which wereE. coliandP. aeruginosa. Additionally, it was found that the proportion of multidrug-resistant bacteria was relatively large, and caution should be used in the application of antibiotics. The extrapancreatic infection time was usually earlier than the pancreatic infection time. For patients with suspected extrapancreatic infection, blood and respiratory pathogen culture should be prioritized. Third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins or carbapenems can be used as empirical antibiotics. Persistent organ failure, multidrug resistance, and surgery were risk factors for death.

Research perspectives

We confirmed the common infectious strains, the site of infection, and the time of infection in NP patients with infectious complications. Through these results, we found that it is helpful for clinicians to evaluate the patient's condition in a timely manner to improve the patient's prognosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In the process of revise our article, we received the support from the Construction Project of Clinical Advanced subjects of Capital Medical University and the valuable advice and help of Professor Zhang Taiping, from basic surgery of Beijing Union Medical College. We would like to say thank you for them.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Diagnostic and prognostic potential of tissue and circulating long non-coding RNAs in colorectal tumors

- Autoantibodies: Potential clinical applications in early detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma

- Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the screening and follow-up of high-risk individuals for familial pancreatic cancer

- Hepatic senescence, the good and the bad

- Optimizing proton pump inhibitors in Helicobacter pylori treatment:Old and new tricks to improve effectiveness

- Regulatory effect of a Chinese herbal medicine formula on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease