Distribution of high-risk human papillomavirus genotype prevalence and attribution to cervical precancerous lesions in rural North China

2019-09-10ShuangZhaoXuelianZhaoShangyingHuJessicaLuXianzhiDuanXunZhangFengChenFanghuiZhao

Shuang Zhao, Xuelian Zhao, Shangying Hu, Jessica Lu, Xianzhi Duan, Xun Zhang, Feng Chen,Fanghui Zhao

1Department of Epidemiology, National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100021, China; 2Biology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA; 3Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100176, China; 4Department of Pathology, National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100021, China

Abstract Objective: Precise prevention is more desired for cervical cancer due to the huge population, high prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in China and the vision of screen-and-treat strategies in low- and middleincome countries (LMICs). Considerations of combining type-specific prevalence and attribution proportion to high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia are informative to more precise and effective region-specific cervical cancer prevention and control programs. The aim of the current study was to determine the genotype distribution of HPV and attribution to cervical precancerous lesions among women from rural areas in North China.Methods: A total of 9,526 women participated in the cervical cancer screening project in rural China. The samples of women who tested positive for HPV were retested with a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based HPV genotyping test. The attribution proportion of specific high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) types for different grades of cervical lesions was calculated by using the type contribution weighting method.Results: A total of 22.2% (2,112/9,526) of women were HR-HPV positive and HPV52 (21.7%) was the most common HR-HPV genotype, followed by HPV58 (18.2%), HPV53 (18.2%) and HPV16 (16.2%). The top three genotypes detected in HR-HPV-positive cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)1 were HPV16 (36.7%), HPV58(20.4%), HPV56 (15.3%). Among CIN2+, the most frequent genotypes were HPV16 (75.6%), HPV52 (17.8%),HPV58 (16.7%). HPV16, 56, 58, 53, 52, 59, 68, and 18 combined were attributed to 84.17% of all CIN1 lesions,and HPV16, 58, and 52 combined were attributed to 86.98% of all CIN2+ lesions.Conclusions: The prevalence of HR-HPV infection among women from rural areas in North China was high and HPV16, HPV58, HPV52 had paramount attributable fraction in CIN2+. Type-specific HPV prevalence and attribution proportion to cervical precancerous lesions should be taken into consideration in the development of vaccines and strategy for screening in this population.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus; cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; genotype distribution; attribution proportion; cervical cancer

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the 4th most commonly diagnosed cancer in women globally, and it is the 2nd most diagnosed in women living in less-developed regions (1).GLOBOCAN 2018 estimates that there were an estimated 569,847 new cases and approximately 311,365 deaths from cervical cancer worldwide (1). A large majority of the cervical cancer burden occurs in less-developed regions (2).In mainland China, the incidence rate of cervical cancer is estimated to be about 15.4/100,000 and cervical cancer is the 8th leading cause of cancer deaths in Chinese women based on 2018 data, with the mortality rate being as high as 6.9/100,000 (3).

Persistent high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV)infection is the most important cause of the progression of cervical cancer and its precursors. There are more than 150 HPV types being identified and at least 13 of them are regarded as “high risk” contributing to the development of cervical cancer including HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51,52, 56, 58, 59, and 68 (4); it has been suggested that their relative carcinogenic potential varies enormously (5), which causes different attributable proportions to cervical cancer.HPV infection rates and genotype distributions vary between different regions and countries, causing cervical cancer incidence and mortality to vary geographically as well (6,7). Due to the huge population, high prevalence of HPV infection in China and the vision of screen-and-treat strategies in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)(8), precise prevention is more desired for cervical cancer in China. Obtaining knowledge of high-risk genotype attribution to high grades of cervical lesions will benefit to risk stratification of HPV positive women and determine who deserve special attention during screening in countries that adopt the screen-and-treat programs. Meanwhile,although both quadrivalent and nonavalent Gardasil®, as well as Cervarix®, have been used in the Chinese mainland since 2017 for the primary prevention of cervical cancer, no vaccine has been incorporated into the National Immunization Program yet. Baseline data of HPV prevalence before vaccinations are essential to establish the impact of vaccination on the distribution of HPV types.This also helps provide logistical information for the development of second-generation HPV vaccine.

In 2017, we conducted the Point of Care (POC) for Cervical Cancer Screening and Management in Lowresource Settings in China study (CMB-OC) in Inner Mongolia and the Shanxi Province of China. In this study,we described the distribution and attribution of HR-HPV genotypes for cervical precancerous lesions in North China. All participants in this study collected cervical exfoliated cells to do polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based and careHPV testing. The samples of women with positive HPV screening results (careHPV or PCR HPV test without genotyping) were retested with a PCR-based HPV genotyping test.

Materials and methods

Study population and ethics approval

In 2017, 9,526 women participated in the POC for Cervical Cancer Screening and Management in Low-resource Settings in China project. This study took place in three rural areas in China: Xiangyuan and Yangcheng County in Shanxi Province, and Etuoke County in Inner Mongolia.Participants were enrolled according to the including criteria: 1) aged 30-65 years old; 2) were not pregnant; 3)had intact cervix; and 4) had no history of cervical neoplasia. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cancer Institute/Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CICAMS).

Screening procedures

Interested eligible women gave written informed consent after study procedures were explained in detail. At this time, a questionnaire about socio-demographic, sexual,reproductive, medical, and HPV infection-related characteristics was collected as well. Once this step was completed, sampling kits were given to the participants and township health providers would instruct the participants how to self-collect cervico-vaginal samples. After that, the samples were sent to the central laboratory of the respective county. Here, local trained laboratory technicians performed PCR-based and careHPV testing(the agreement between the two methods was 89.9%,κ=0.646; substantial agreement); the self-collected samples with initial HPV positive results (careHPV or PCR HPV test without genotyping) were retested with another HPV genotyping test. Women with positive results in either of the HPV tests were referred for a colposcopy, and the gynecologist undertook a punch biopsy if any cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) lesion (low-grade lesion or worse) was suspected on colposcopy evaluation. The principles of treatment were based on the guidelines of implementation for project.

Detection and genotyping of HPV

CareHPV testing (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA)

CareHPV testing is based on nucleic acid hybridization detection, targeting 14 high-risk HPV types (HPV16, 18,31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68). However,careHPV testing cannot determine the specific HPV genotype. The test measures the ratio of relative light units emitted by microplate reader (RLU) to cutoff (CO). If the RLU/CO value ≥1.0, the participant is considered to be high-risk HPV positive; otherwise, considered to be highrisk HPV negative.

PCR-based HPV testing without genotyping (Sansure,Changsha, China)

Sansure PCR HPV testing employs the One-Step Fast Release technology, targeting 15 HR-HPV types (HPV16,18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68), and has been approved by a European Union Certificate (CE).By applying real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR, the testing utilizes pairs of specific primers and specific probes accompanied with other reagents in the PCR mix to achieve rapid detection of HR-HPV DNA. The manual sample processing requires about 45 min by minimally trained personnel prior to an automated detection procedure, which can be completed within 1 h and 20 min.HPV positivity is measured by the cycle numbers observed(Ct) when the fluorescent signal reaches the set threshold.A Ct ≤39 is considered HPV positive and a Ct >39 is considered negative.

HPV test with genotyping (Sansure, Changsha, China)

Subsequent genotyping for HR-HPV types (HPV16, 18,31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68) was performed according to the above-mentioned PCR test principles and workflow but with detection of the exact types.

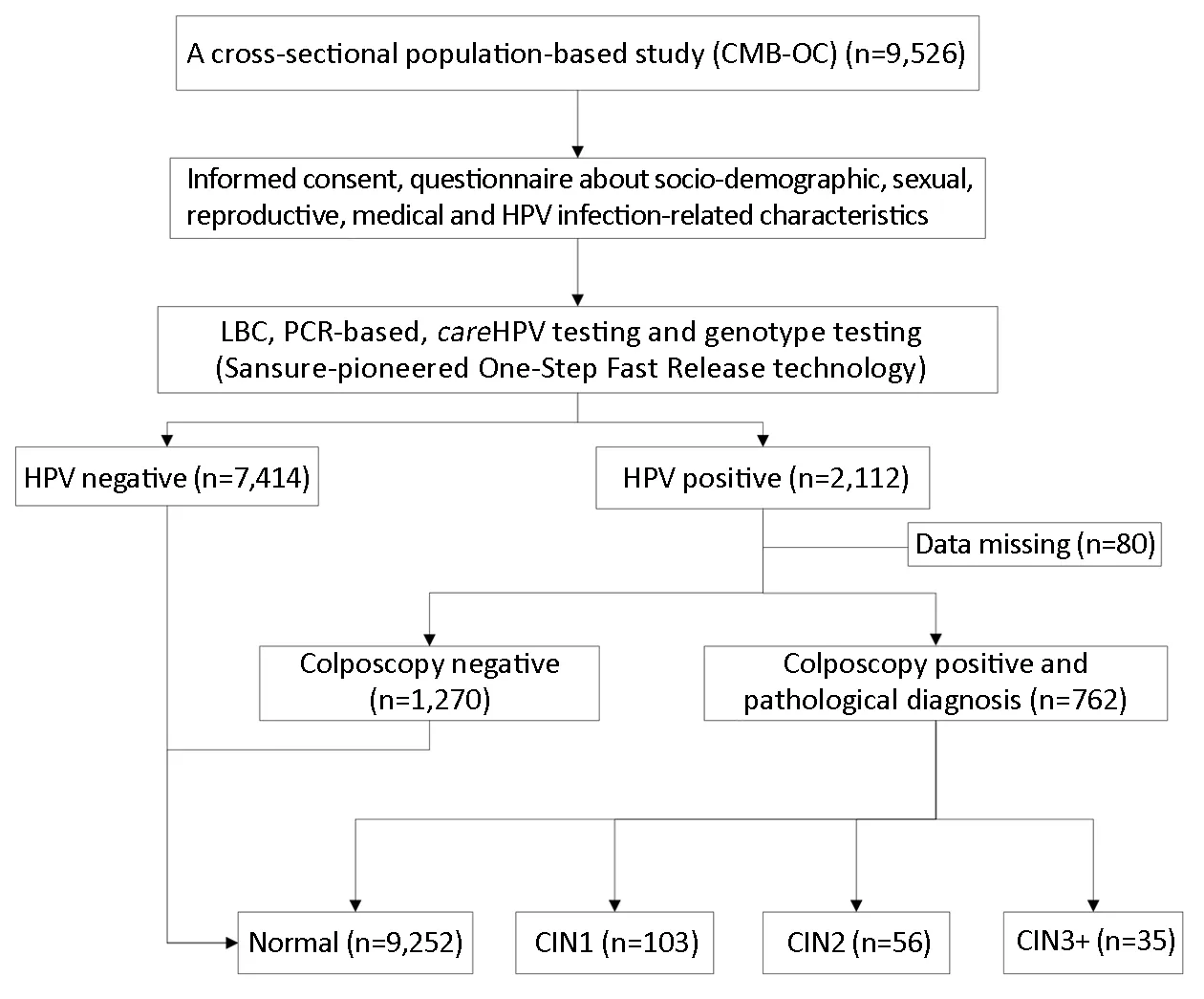

Confirmation of disease status

Pathology was the gold-standard endpoint measure.Experienced pathologists at CICAMS reviewed every histology slide and classified each finding as negative, CIN grade 1/2/3, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC),adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), or adenocarcinoma (ADC).For women initially without pathological results, final classification was based on the overall combination of testing measures. To exclude verification bias, we applied the following criterion for final analysis: women without biopsies were classified as normal if they either had a negative colposcopy impression or if they had negative results for the HR-HPV test both in careHPV and PCR HPV tests (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Screening flowchart. CMB-OC, Point of Care (POC) for the Cervical Cancer Screening and Management in Low-resource Settings in China study; HPV, human papillomavirus; LBC, liquid-based cytology; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CIN1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1; CIN2, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2; CIN3+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse.

It should be noted that local laboratory technicians and physicians involved in this study were trained uniformly by CICAMS and WHO/IARC experts in preparation for this study.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were focused on the description of distribution and attribution of HR-HPV genotypes for cervical precancerous lesions in China. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants were described using means,standard deviations (SD), frequencies, and proportions;comparisons of characteristics of different grades of cervical lesions (normal, CIN1, CIN2 and CIN3+) were conducted by Pearson χ2or Fisher's exact tests, as appropriate. The calculations of attributable proportions of lesions caused by specific HPV types have been described in a previous paper(9-11). In short, the proportion of single infection HPV genotype among the population in the same pathological grade was used as the standard for evaluating the contribution ratio of each genotype for individuals with single or multiple infections. If, for example, there are 6 single-type HPV16 incidences and 4 single-type HPV18 for CIN2 cases, the derivation of the attributable portion of each genotype for 2 CIN2 lesions positive for both HPV16 and 18 in a study is as follows: 2×6/(6+4)=1.2 of these 2 multi-type infected lesions would be attributed to HPV16,and 2×4/(6+4)=0.8 would be attributed to HPV18. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics(Version 23.0; IBM Corp., NewYork, USA). We considered P<0.05 to be statistically significant, and all tests performed were two-sided.

Results

General characteristics

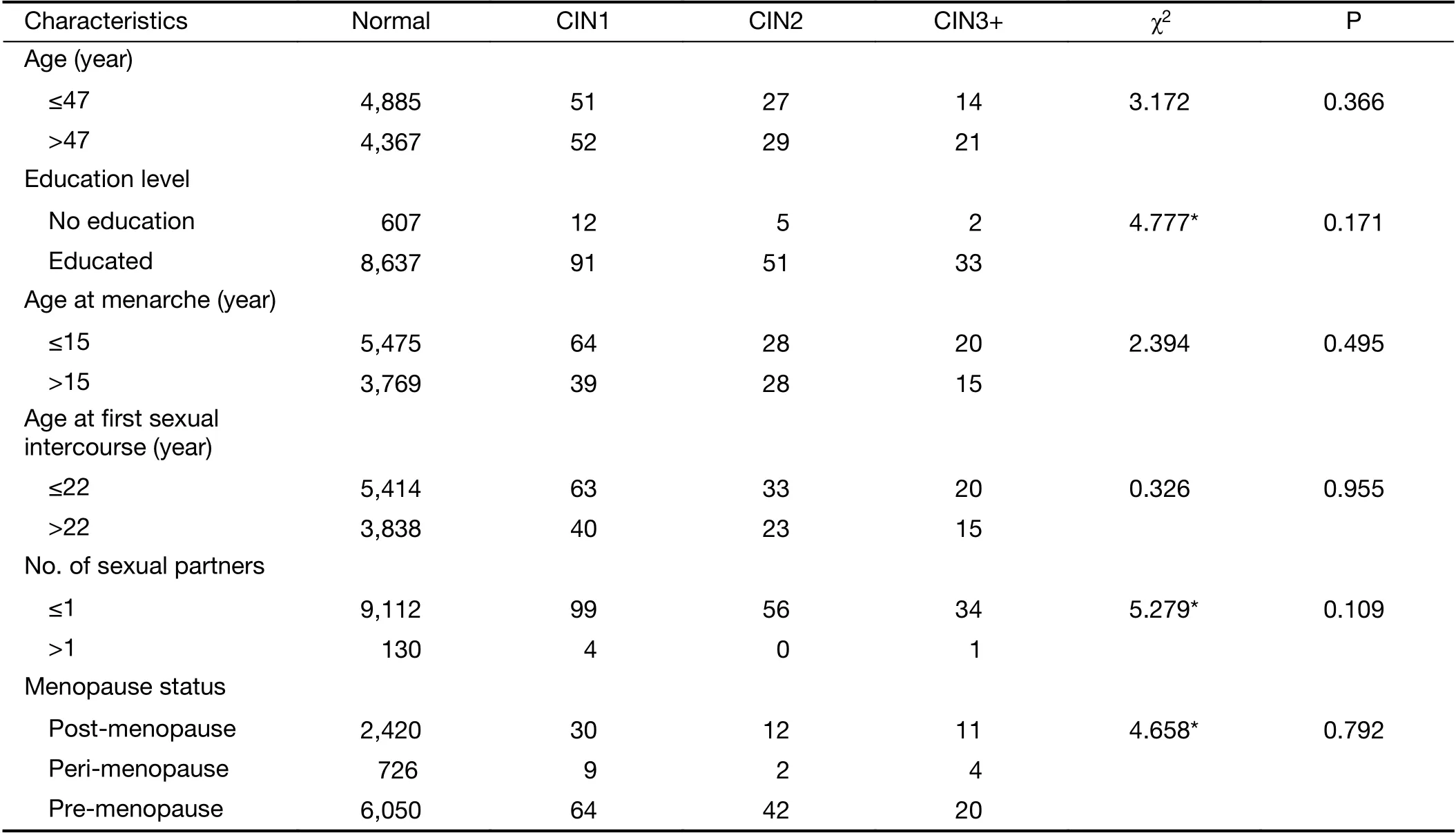

A total of 9,526 women were included in the final analysis.The mean age of participants was 47.3±7.8 years old, the mean age at menarche was 15.2±2.0 years old, and the mean age of first sexual intercourse was 22.2±2.1 years old.About 1.4% (135/9,516) had more than 2 sexual partners,and 26.4% (2,504/9,469) were post-menopause.Additionally, 70.0% of participants (6,663/9,518) had middle school-level or higher education.

Among the 9,526 women, 2,112 (22.2%) women were positive for either careHPV or PCR HPV test without genotyping, in which 88.7% (1,874/2,112) were infected with specific HPV genotypes. All HPV-positive participants had colposcopy except 80 women lost to follow-up. Finally, 9,252 (97.1%) were pathologically normal, 103 (1.1%) had CIN1, and 91 (1.0%) had CIN2+.We set the mean age (47 years old) as the criterion for stratifying the women into subgroups, 15 years old as an early age for menarche, and 22 years old as an early age for first sexual intercourse. The analyses discussed later were performed among the stratified age groups. There was no statistically significant correlation between demographic characteristics and cervical lesion severity (Table 1).

Distribution of HR-HPV among different grades of cervical lesions

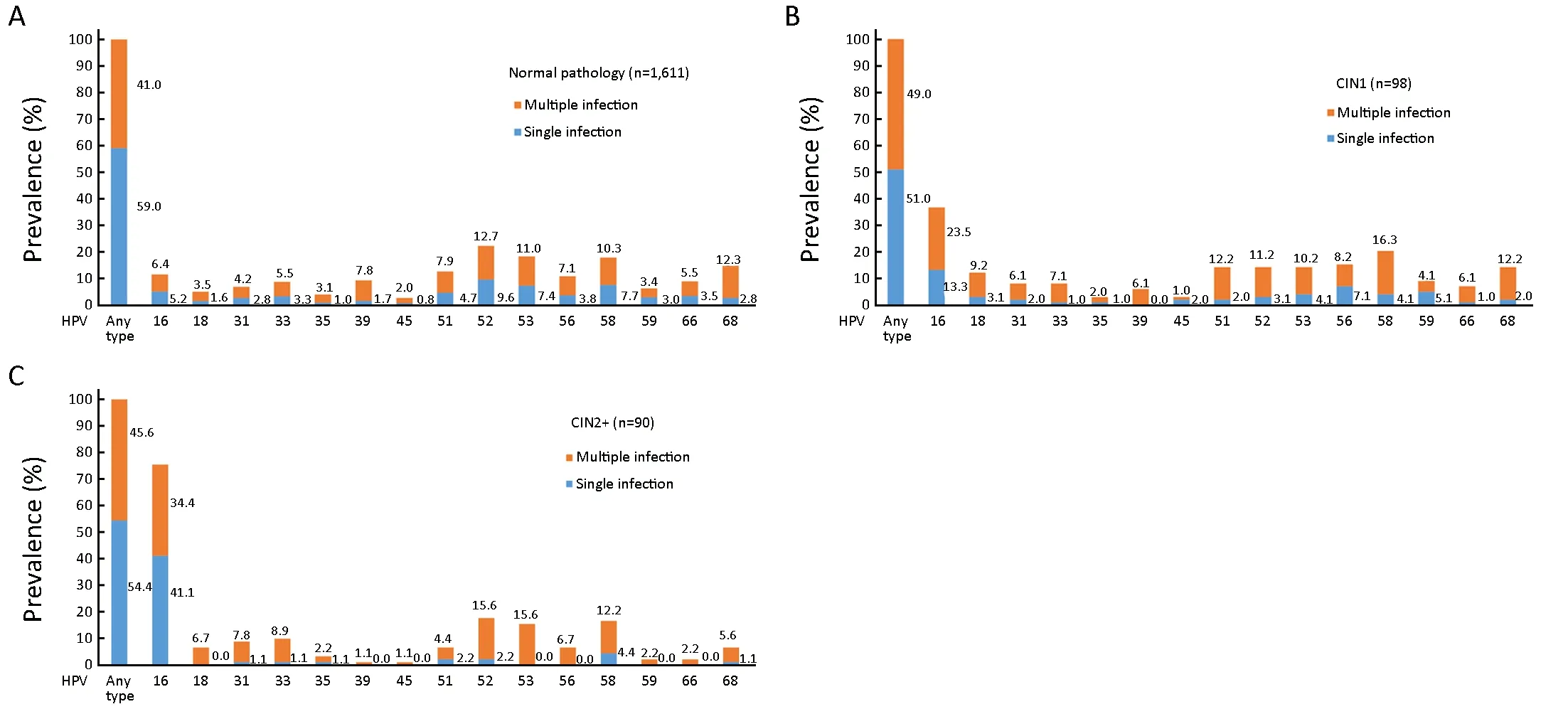

Among the 1,874 women (19.7%, 1,874/9,526) with HRHPV positive for any of 15 HR-HPV types, and HPV52(21.7%) was the most common HR-HPV genotype. This is followed by HPV58 (18.2%), HPV53 (18.2%), HPV16(16.2%), and HPV68 (14.8%). The prevalence of HPV in normal pathology, CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3+ were 17.4%(1,611/9,252), 95.1% (98/103), 98.2% (55/56), and 100.0%(35/35), respectively. HPV prevalence is positively correlated with cervical lesion severity (χ2=779.312;P<0.001; Ptrend<0.001).

Among women with normal pathology results, the 6 most prevalent HR-HPV types were HPV52 (22.3%),HPV53 (18.4%), HPV58 (18.0%), HPV68 (15.1%),HPV51 (12.7%) and HPV16 (11.6%). For women with CIN1, the most prevalent HR-HPV types were HPV16(36.7%), HPV58 (20.4%), HPV56 (15.3%), HPV52(14.3%), HPV51 (14.3%), HPV53 (14.3%), and HPV68(14.3%); for women with CIN2+, the most frequent genotypes were HPV16 (75.6%), HPV52 (17.8%), HPV58(16.7%), HPV53 (15.6%), HPV33 (10.0%), and HPV31(8.9%).

The proportions of single and multiple infections among women were 59.0% (951/1,611) and 41.0% (660/1,611) in normal pathology; 51.0% (50/98) and 49.0% (48/98) in CIN1; 50.9% (28/55) and 49.1% (27/55) in CIN2; and 60.0% (21/35) and 40.0% (14/35) in CIN3+, respectively.The trend test showed no significance (χ2=1.331; P=0.249)(Figure 2).

The prevalence of HPV16 was positively correlated with the severity of cervical lesions (11.6% in normal, 36.7% in CIN1, 65.5% in CIN2, 91.4% in CIN3+, Fisher's Exact=546.876; P<0.001) (Table 2).

Attributable proportion of HPV in different grades of cervical lesions

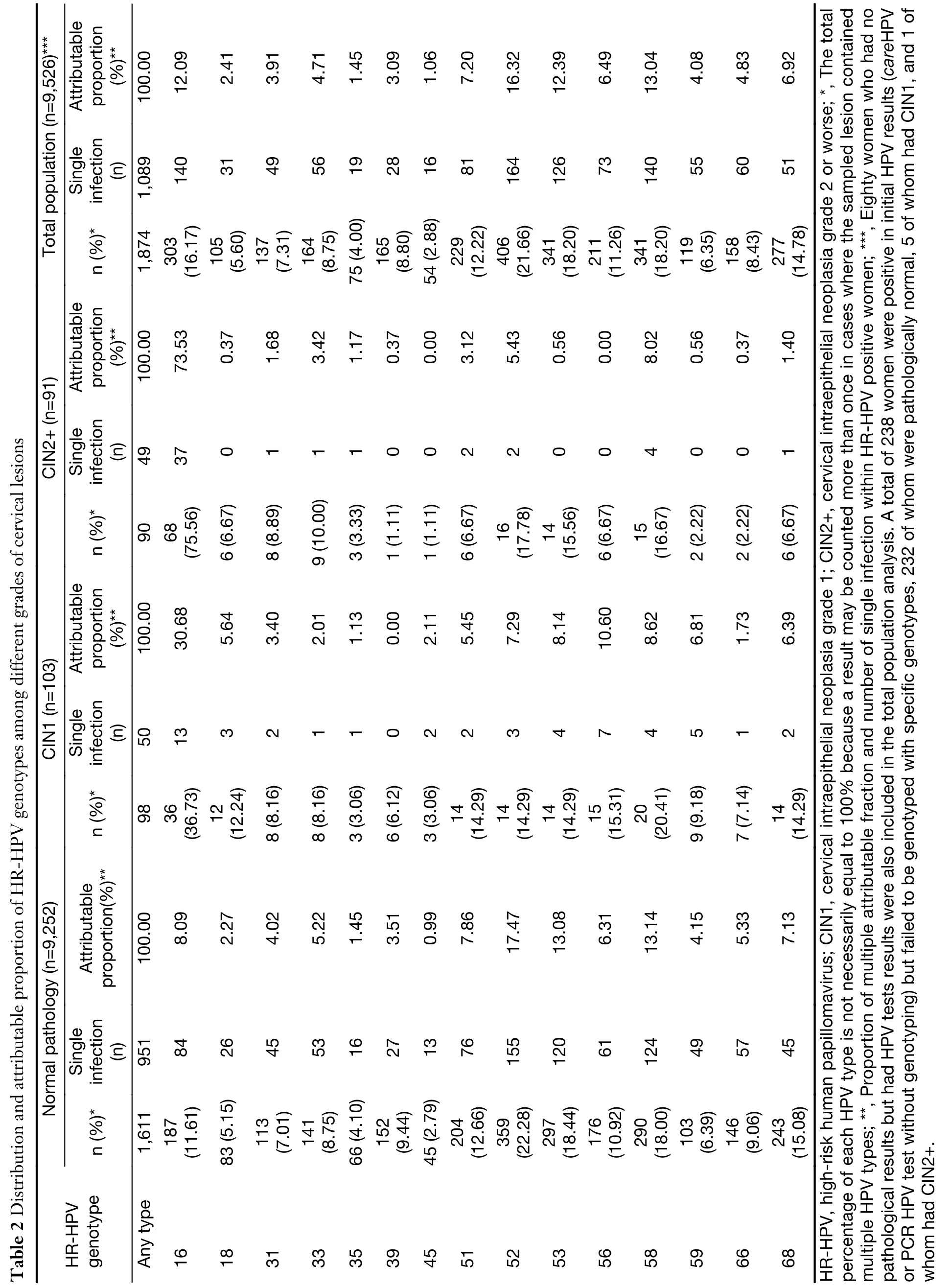

The prevalence of specific HPV types in different grades ofHR-HPV-positive cervical lesions, along with an estimate of the attributable fraction of HPV (defined as an estimate of the proportion of lesions caused by a given HPV type),was shown in Table 2.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of study population correlated to cervical lesion severity

Figure 2 Distribution of high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) genotypes in different grades of cervical lesions. (A) Normal pathology; (B) CIN1; (C) CIN2+. HPV, human papillomavirus; CIN1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1; CIN2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse.

Total population (n=9,526)***Attributable proportion)**(%100.00 12.09 2.41 3.91 4.71 1.45 3.09 1.06 7.20 16.32 12.39 6.49 13.04 4.08 4.83 6.92 Single infection(n)1,089 140 31 49 56 19 28 16 81 164 126 73 140 55 60 51 n (%)*1,874 303(16.17)105(5.60)137(7.31)164(8.75)75 (4.00)165(8.80)54 (2.88)229(12.22)406(21.66)341(18.20)211(11.26)341(18.20)119(6.35)158(8.43)277(14.78)Attributable proportion)**100.00(%73.53 0.37 1.68 3.42 1.17 0.37 0.00 3.12 5.43 0.56 0.00 8.02 0.56 0.37 1.40 Table 2 Distribution and attributable proportion of HR-HPV genotypes among different grades of cervical lesions CIN2+ (n=91)Single infection(n)49 37 0 1 1 1 0 0 2 2 0 0 4 0 0 1 n (%)*90 68(75.56)6 (6.67)8 (8.89)9 (10.00)3 (3.33)1 (1.11)1 (1.11)6 (6.67)16(17.78)14(15.56)6 (6.67)15(16.67)2 (2.22)2 (2.22)6 (6.67))**Attributable proportion(%100.00 30.68 5.64 3.40 2.01 1.13 0.00 2.11 5.45 7.29 8.14 8.62 6.81 1.73 6.39 CIN1 (n=103)10.60 Single infection(n)50 13 3 2 1 1 0 2 2 3 4 7 4 5 1 2 n (%)*98 36(36.73)12(12.24)8 (8.16)8 (8.16)3 (3.06)6 (6.12)3 (3.06)14(14.29)14(14.29)14(14.29)15(15.31)20(20.41)9 (9.18)7 (7.14)14(14.29)Normal pathology (n=9,252)Attributable)**proportion(%100.00 8.09 2.27 4.02 5.22 1.45 3.51 0.99 7.86 17.47 13.08 6.31 13.14 4.15 5.33 7.13 Single infection(n)951 84 26 45 53 16 27 13 76 155 120 61 124 49 57 45 n (%)*1,611 187(11.61)83 (5.15)113(7.01)141(8.75)66 (4.10)152(9.44)45 (2.79)204(12.66)359(22.28)297(18.44)176(10.92)290(18.00)103(6.39)146(9.06)243(15.08)HR-HPV genotype Any type 16 18 31 33 35 39 45 51 52 53 56 58 59 66 68 HR-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus; CIN1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1; CIN2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse; *, The total percentage of each HPV type is not necessarily equal to 100% because a result may be counted more than once in cases where the sampled lesion contained multiple HPV types; **, Proportion of multiple attributable fraction and number of single infection within HR-HPV positive women; ***, Eighty women who had no pathological results but had HPV tests results were also included in the total population analysis. A total of 238 women were positive in initial HPV results (careHPV or PCR HPV test without genotyping) but failed to be genotyped with specific genotypes, 232 of whom were pathologically normal, 5 of whom had CIN1, and 1 of whom had CIN2+.

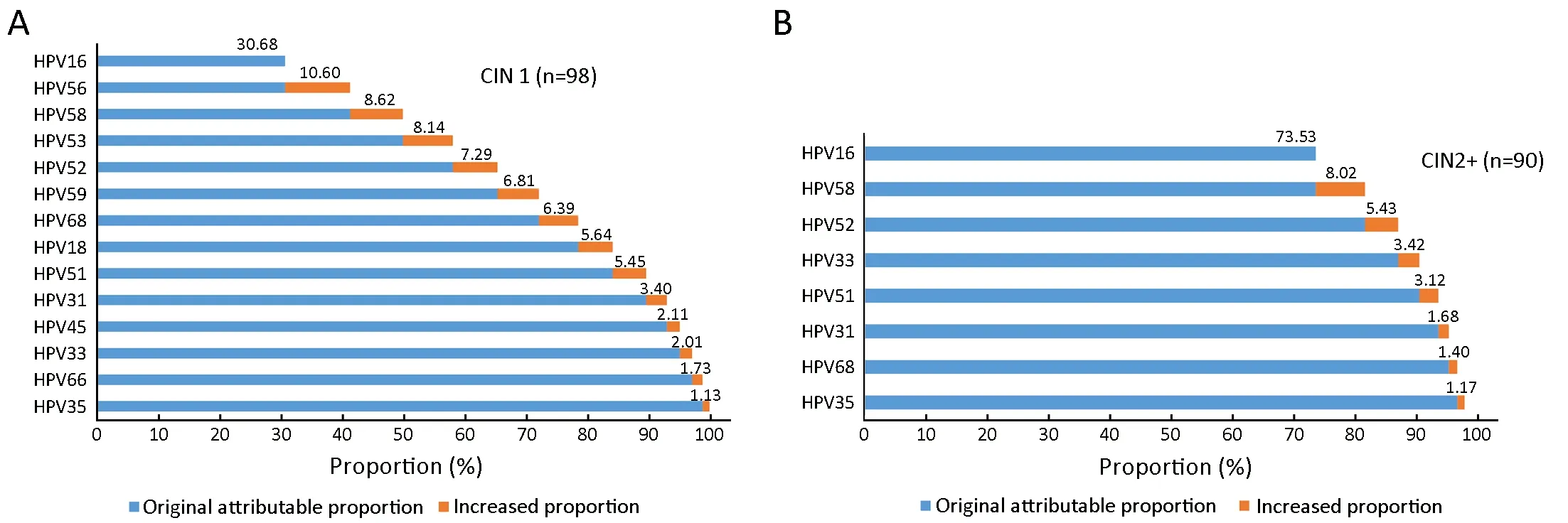

HPV16 was attributed to 30.68% of CIN1, 73.53% of CIN2+; it was the genotype with the highest attributable proportion observed in CIN1 and CIN2+ (Figure 3).

In total, HPV16, 56, 58, 53, 52, 59, 68, and 18 combined were attributed to 84.17% of all CIN1 lesions, and HPV16,58, and 52 combined were attributed to 86.98% of all CIN2+ lesions (Figure 3).

Discussion

This cross-sectional population-based study describes the distribution of high-risk HPV and their respective attribution proportions to cervical precancerous lesions among women from rural areas in North China. Overall,HR-HPV prevalence was 22.2% (2,112/9,526), which is higher than the pooled analysis from 17 population-based studies throughout China which indicated HR-HPV prevalence was 18.0% in rural women (12); this is attributed to prevalence results arising from positive for careHPV or PCR HPV testing without genotyping. In our study, HPV52 was the most commonly detected HR-HPV types in cervical specimens which was consistent with other studies conducted in Jiangsu, Guangdong and other provinces (13,14). However, some other studies found that HPV16 was the most common genotype (15-17). All these indicate that HPV genotype distributions vary between different regions. Simultaneously, it is important to note that the overall HPV genotype distribution and attribution proportion of each genotype in the rural Chinese population are not quite the same as that of elsewhere worldwide. A worldwide pooled analysis showed that HPV16, 18 and 45 were the most prevalent types of HPV associated with cervical lesions globally (10); and consistent with the review, the highest attribution rates of genotypes in CIN2+ was also HPV 16 in our study. Nevertheless,there were some distinguished characteristics. Firstly, the attributable proportion for HPV18 was not as high as it is in the study above. The reason may be that HPV18 is associated with adenocarcinoma (18) and was more frequently present in cancer rather than in precancerous lesions (19); because of the limited number of cervical cancer incidences, we may have limited power to evaluate attributable risk of HPV18 in this population, and have potentially underestimated the attributable proportion of HPV18. Secondly, the attribution of HPV 52 and HPV 58 to CIN2+ in China were frequently detected and preceded only by HPV 16, rather than HPV 45, which means HPV52 and HPV58 are more prevalent among Chinese rural women with CIN2+. Therefore, research carried out on the distribution and attribution of various HR-HPV types in worldwide may not be wholly applicable to Chinese women. The distinguished characteristics of cervical HPV infection in China should be considered when designing HPV screening assays and vaccines.

Figure 3 Cumulative attribution proportion of 15 (HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68) high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) genotypes for cervical intraepithelial lesions. Among the 15 HR-HPV genotypes, genotypes with ≤1% were not displayed. Accumulated numbers are represented in boldface. (A) CIN1; (B) CIN2+. CIN1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1; CIN2+,cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 or worse.

Currently, bivalent Cervarix® and both quadrivalent and nonavalent Gardasil® are approved by China's Food and Drug Administration (FDA), however the HPV vaccine has not incorporated into the National Immunization Program.Analysis of this study results will contribute to provide critical epidemiological evidence and baseline data for future evaluation of the impact of the National HPV Vaccination Program in mainland China. Besides, getting knowledge of the distribution of HPV types in different cervical lesions will benefit to estimate the potential protection provided by current HPV vaccines. And the determination of the most common HPV types in cervical lesions can influence the development of new polyvalent HPV vaccines. Our study suggests that HPV16, HPV52,and HPV58 play important roles in the development of cervical lesions in rural North China, and these particular HPV carcinogenic types should be given priority in the development of new polyvalent HPV vaccines. Moreover,based on the ecological principles, there exists competitive restraint between different strains and types, and so also is HPV. Elimination of one strain/type via vaccination may cause an increase in prevalence of other untargeted HPV vaccine genotypes because of reduced competition during natural infection. A study undertaken in US compared the HPV prevalence between HPV-vaccinated and nonvaccinated young adult women (20-26 years old) and reported that compared to the unvaccinated women,vaccinated women had a higher prevalence of nonvaccine high-risk types including HPV39, 52, 53 (20). Therefore,surveillance on the prevalence and attribution of HPV genotypes after wide spread use of vaccines in East Asia is important to identify type replacement early if it ever happens (21,22)

Because of vaccines' high prices, vaccination coverage is still very low in China, especially in low-resource areas. In such regions, screening takes precedence over vaccinations in the prevention of cervical cancer.

In our study, HR-HPV genotype distribution and attribution to cervical precancerous lesions are based on the self-collected cervicovaginal specimens tested for HPV DNA (Self-HPV testing). Self-sampling, as an alternative for the collection of a clinician sample, could become the new paradigm for primary cervical cancer screening in the general population. Most studies made that conclusion based on the evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of self-HPV testing and physician-HPV testing (23). Our results indicated the paramount role of HPV16, 33, 51, 52, 58 attributable to CIN2+, which is consistent with the result of previous study using clinician-collected cervical samples(9). Our study further validates that the identical HR-HPV genotypes need to be focused on using self-HPV testing and physician-HPV testing in terms of the attribution proportion to CIN2+. A population-based cohort study in China using physician-collected samples indicated that HPV 16 and HPV 31 had the highest cumulative risk of CIN2+ within 10-year follow-up, followed by HPV 58, 39,33, 52, and 18 (24). This was one of the very few studies to evaluate the predictive value of type-specific HPV in detecting cervical cancer and precancers in a Chinese population-based cohort, and it remains a need for more prospective studies with greater sample sizes to identify specific HR-HPV genotype attributable to CIN2+.HPV16, HPV58, and HPV52 combined were attributed to 87.0% of all CIN2+ lesions in our study; HPV52 and HPV58 were attributed to 13.5% of CIN2+ cases. Based on our cross-sectional study, besides HPV16, HPV52, 58 may also deserve special attention if HPV self-sampling rolls out as primary screening in general population. In accordance with updated screening guidelines (25), only HPV 16/18 positive women were recommended for direct referral to colposcopy, and non-16/18 HR-HPV positive women were recommended for triaging with cytology to colposcopy.Our follow-up results will contribute to further clarify whether other HR-HPV genotypes positive women,besides HPV 16/18, should directly be referred to colposcopy. It seems that HPV52 and HPV58 may warrant special attention in screening procedures in these regions.Consideration of combining type-specific HPV prevalence and attribution proportion to high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia could be informative to more precise and effective region-specific cervical cancer screening programs.

Our study does have some limitations. In present study,238 (11.3%) women with either careHPV or PCR HPV positive results failed to be genotyped with specific genotypes, which was also documented in a recent study,presenting a crude agreement of 73.27% between hybrid capture 2 (HC2) test and SPF10-LiPA system in detecting carcinogenic HPV genotypes (26). The potential bias between initial HPV tests and HPV genotyping test is mainly due to the different detection threshold and the interpretation randomness of the samples near the detection threshold, etc.

Conclusions

This study suggested the prevalence of HR-HPV infection among women from rural areas in North China was high.HPV16, HPV52, and HPV58 were the most dominant high-risk genotypes in these population and attributed to 87.0% of all CIN2+ lesions. Type-specific HPV prevalence and attribution proportion to cervical precancerous lesions should be taken into consideration in the development of vaccines and strategy for screening in this population.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the China Medical Board(CMB) (No: 16-255); and Chinese Academy of Medical Science Initiative for Innovative Medicine (No: 2017-I2M-1-002).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

杂志排行

Chinese Journal of Cancer Research的其它文章

- Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of melanoma 2018 (English version)

- An update on biomarkers of potential benefit with bevacizumab for breast cancer treatment: Do we make progress?

- Association of cancer prevention awareness with esophageal cancer screening participation rates: Results from a populationbased cancer screening program in rural China

- FAT1, a direct transcriptional target of E2F1, suppresses cell proliferation, migration and invasion in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Clinical significance of MET gene amplification in metastatic or locally advanced gastric cancer treated with first-line fluoropyrimidine and platinum combination chemotherapy

- A 18FDG PET/CT-based volume parameter is a predictor of overall survival in patients with local advanced gastric cancer