粪菌移植治疗儿童复发性艰难梭菌感染6例临床疗效评价

2018-08-05李小露王怡仲李丹张婷肖咏梅

李小露 王怡仲 李丹 张婷 肖咏梅

摘 要 目的:探讨粪菌移植治疗儿童复发性艰难梭菌感染(recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, RCDI)的临床疗效。方法:收集上海市儿童医院消化科2014—2016年间收治的6例RCDI患儿接受粪菌移植治疗的临床资料。通过分析患儿的性别、年龄、临床表现、腹部CT检查图像以及粪菌移植治疗的次数、剂量和给予途径来评估粪菌移植治疗儿童RCDI的临床疗效。结果:共入组6例患儿。2例患儿经单次粪菌移植治疗达到临床治愈,4例患儿经多次粪菌移植治疗达到临床治愈。6例患儿在粪菌移植治疗期间及之后的随访中均未出现严重的不良反应。结论:粪菌移植治疗可用于儿童RCDI,其治疗有效且安全、耐受性好。

关键词 粪菌移植 艰难梭菌感染 临床疗效

中图分类号:R725.1 文献标志码:B 文章编号:1006-1533(2018)13-0010-05

Clinical efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation for pediatric recurrent Clostridium difficile infection*

LI Xiaolu, WANG Yizhong, LI Dan, ZHANG Ting, XIAO Yongmei**

(Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Shanghai Childrens Hospital, Shanghai 200062, China)

ABSTRACT Objective: To evaluate the clinical efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) on children with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (RCDI). Methods: Clinical data from 6 patients diagnosed as RCDI and treated with FMT at Shanghai Childrens Hospital from 2014 through 2016 were analyzed. The clinical efficacy of FMT for RCDI was evaluated by analysis of the gender, age, clinical manifestation, abdominal CT examination images of children and the frequency, dose, and route of FMT. Results: Among the 6 patients, 2 children received a single FMT treatment and achieved clinical cure and 4 children were treated with multiple FMT and achieved clinical cure. No severe adverse reaction occurred during FMT and followup. Conclusion: FMT can be used to treat children with RCDI and its treatment is effective, safe and well tolerant.

KEY WORDS fecal microbiota transplantation; Clostridium difficile infection; clinical efficacy

艰难梭菌感染(Clostridium difficile infection, CDI)是指由艰难梭菌引起的感染。CDI的临床表现轻重不一,包括无症状、轻度腹泻、结肠炎和严重的伪膜性肠炎等。近年来,随着抗生素的广泛使用,CDI的发病率越来越高。在过去的10年里,儿童和成人CDI的发病率增加了1倍[1],其中儿童发病率最高的年龄段在1 ~ 4岁[2]。目前,常规治疗CDI的抗生素有万古霉素、甲硝唑和非达霉素等[3]。经抗生素初阶段治疗后的CDI的复发率为10% ~ 20%,但经抗生素第二阶段治疗后的CDI的再次复发率高达45% ~ 60%[3]。粪菌移植(fecal microbiota transplantation)是指将自健康人(供体)粪便中分离出的菌群、病毒等多种微生物以及食物分解、消化后和肠道微生物产生的各种代谢产物、天然抗菌物质等,通过鼻胃管、十二指肠管、胃镜或结肠镜等途径注入到患者肠道内,以重建肠道微生态平衡、修復肠黏膜屏障、控制炎症反应、调节机体免疫,进而治疗特定的肠道内和肠道外疾病的一种特殊方法[4-6]。研究显示,粪菌移植治疗对复发性CDI(recurrent CDI, RCDI)有效,其临床治愈率可达90%以上[7]。不过,有关粪菌移植治疗儿童RCDI的研究不多,且多为病例报告,报告的治疗成功率在90% ~ 100%间[8-12]。本研究回顾性分析上海市儿童医院消化科应用粪菌移植治疗儿童RCDI的临床疗效,为进一步开展儿童RCDI粪菌移植治疗研究提供临床依据。

1 对象和方法

1.1 研究对象

研究对象为上海市儿童医院消化科2014—2016年收治的6例RCDI患儿。

2018年2月,美国感染病学会(Infectious Diseases Society of America)和美国卫生保健流行病学学会(Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America)联合发布了最新版的艰难梭菌感染诊治指南[13]。该指南对CDI的定义为:①24 h内有≥3次未成形的大便;②粪便中检测出产毒素的艰难梭菌或其毒素,结肠镜或组织病理学检查结果提示为伪膜性肠炎。

本研究对入组患儿的要求为:诊断为CDI且经抗生素规则治疗无效或又出现复发。临床治愈的标准为:由CDI引起的腹泻、腹痛等症状消失,粪便检测艰难梭菌毒素结果为阴性。

本研究经上海市儿童医院医学伦理委员会审查和批准,所有入组患儿的监护人均签署了知情同意书。

1.2 研究方法

1.2.1 供体的选择

供体包括患儿父母和健康志愿者,均要求身体健康、生活规律,无酗酒、抽烟等不良生活习惯,排便规律、粪便性状正常,无胃肠道疾病史、无自身免疫疾病及其免疫治疗史、无慢性疼痛和神经系统疾病史。供体的血液学筛查包括肝功能、甲型/乙型/丙型肝炎病毒抗体、人免疫缺陷病毒-1/2抗体、巨细胞病毒抗体、梅毒;粪便筛查包括虫卵和寄生虫、粪便常规培养、艰难梭菌毒素检测。

1.2.2 患儿的准备

患儿在接受粪菌移植治疗前需先接受血液學检查,包括肝/肾功能、凝血功能、乙型/丙型肝炎病毒、人免疫缺陷病毒-1/2等,同时接受粪便检查,包括粪常规、培养、病毒检查等。在进行粪菌移植治疗前1 ~ 3 d,对患儿终止抗生素治疗,并给予必要的肠道准备。在粪菌移植治疗前夜,如必要,可给予患儿缓泻剂;在粪菌移植治疗前夜及移植治疗当天早晨,分别给予患儿口服奥美拉唑(每次1 mg/kg,最高20 mg)。

1.2.3 粪菌移植治疗

将150 g供体捐赠的新鲜粪便和200 ~ 300 ml的无菌生理盐水分别加至收集罐内,使用搅拌器搅拌直至内容物变成黏稠、均匀的混悬液,然后使用纱布过滤2次。使用50 ml注射器吸取滤过液,通过胃十二指肠空肠管注入40 ~ 60 ml的滤过液至患儿肠道或以100 ~ 150 ml的滤过液进行直肠保留灌肠,滤过液在患儿肠道内应至少保留4 h以上。

1.2.4 临床疗效评估和随访

记录患儿接受粪菌移植治疗后的预后情况,包括临床症状变化情况、粪便艰难梭菌毒素检测结果、粪菌移植治疗相关的不良反应,评估粪菌移植治疗的临床疗效,并对患儿随访半年。

2 结果

2.1 一般资料

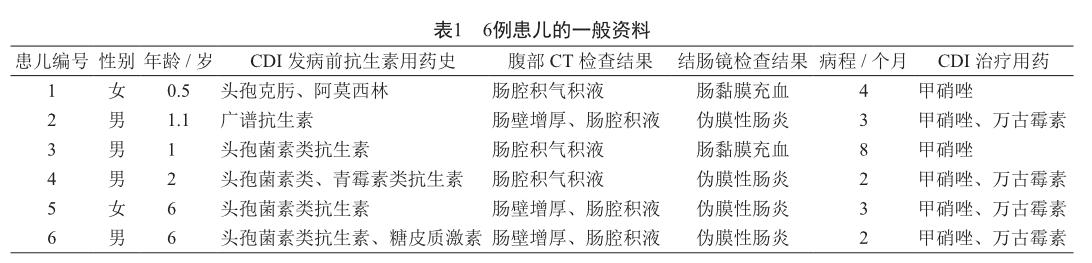

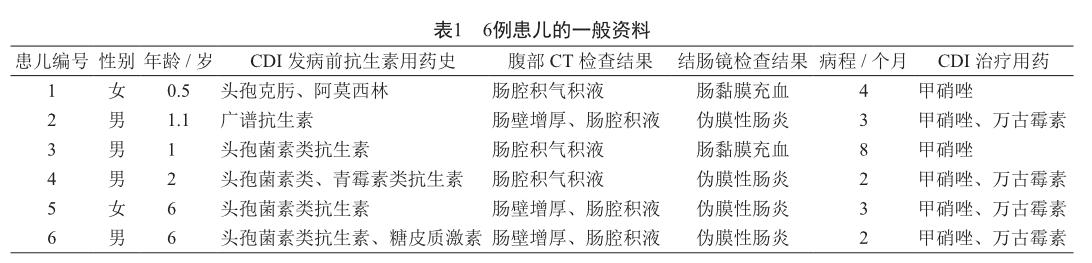

符合本研究纳入及排除标准、临床资料完整的病例共6例,其中男4例、女2例,他们的平均年龄为2.76(0.5 ~ 6)岁。6例患儿在CDI发病前均有抗生素(主要为头孢菌素类和青霉素类抗生素)使用史,病程2 ~ 8个月不等(表1)。6例患儿均接受了结肠镜检查。患儿1、3粪便艰难梭菌毒素检测结果为阳性,患儿2、4、5、6存在伪膜性肠炎。对所有患儿均进行了腹部CT检查,结果显示他们的肠壁增厚,并有肠腔积气积液现象。6例患儿在接受粪菌移植治疗前均接受过甲硝唑和(或)万古霉素规则治疗2周以上,且均为治疗失败或复发病例。

2.2 粪菌移植治疗情况

供体情况,4例为患儿父母,2例为健康志愿者(表2)。粪菌移植治疗途径,对3例患儿通过胃十二指肠空肠管移植,2例患儿通过直肠保留灌肠移植,1例患儿通过胃十二指肠空肠管联合直肠保留灌肠移植。结果显示,6例患儿中有2例接受单次粪菌移植治疗后达到临床治愈,4例经多次粪菌移植治疗后达到临床治愈,单次粪菌移植治疗的治愈率为33%。对所有患儿,粪菌移植治疗后均随访半年,随访方式包括电话询问、门诊就诊。

2.3 预后及不良反应

6例患儿经粪菌移植治疗后均达到了临床治愈,且随访半年均未复发。

总体来说,6例患儿在粪菌移植治疗后均没有发生严重的不良反应。患儿4在粪菌移植治疗当天出现了短暂的腹泻次数增加,第2天自行缓解;患儿5在粪菌移植治疗当天出现发热伴血便,第2天自行消退。其余患儿未出现明显的不良反应。不过,患儿6在随访期间出现短暂的腹痛,后自行缓解。

3 讨论

CDI是院内腹泻的主要原因,其在住院患者中的发病率为0.1% ~ 1%[14-15]。来自北美和欧洲地区的数据表明,20% ~ 27%的CDI是社区获得性的,社区获得性CDI的发病率为0.02% ~ 0.03%[16],但有关儿童CDI发病率的研究较少。美国的一项调查显示,儿童CDI的中位发病年龄为3岁,在总住院患儿中的发病率为0.335%;CDI患儿往往有更长的住院时间、更高的结肠切除率和院内死亡率[17]。常规治疗CDI的抗生素有甲硝唑和万古霉素等,其中口服万古霉素已被推荐为CDI的新的一线治疗方案[13]。有关研究显示,甲硝唑治疗CDI的失败率高达 35%[18],万古霉素治疗的失败率为31%[19],而粪菌移植治疗RCDI的成功率在90%以上[19-20]。2013年,《美国胃肠病学杂志》发表了关于粪菌移植治疗CDI的建议,内容包括患者的肠道准备、治疗剂量、患者和供体的评估等[4]。与成人RCDI的粪菌移植治疗研究相比,对儿童RCDI粪菌移植治疗的研究不多,且以病例报告为主。儿童RCDI的粪菌移植治疗主要通过上消化道(即经鼻胃管或经幽门管)或下消化道(即经结肠镜)途径移植,治疗的成功率达90% ~ 100%[8-12, 21-27]。本研究纳入的6例RCDI患儿经粪菌移植治疗均达到了临床治愈,但与其他研究相比,单次粪菌移植治疗的治愈率明显偏低(33%),考虑可能与粪菌移植治疗的剂量较小和移植后粪菌在患儿肠道的停留时间较短有关。

目前,有关粪菌移植治疗RCDI有效的机制还不完全清楚,可能包括肠道菌群的多样性得到恢复,而正常的肠道菌群可抵御艰难梭菌的持续定植。RCDI患者肠道中的拟杆菌门数量减少,但接受粪菌移植治疗后,他们肠道中的拟杆菌门数量显著增加[28-29]。供体粪便中的细菌代谢产物也可能在抵御RCDI中发挥了作用。粪菌移植治疗可能可上调RCDI患者的固有免疫功能,从而促进患者肠黏膜屏障的修复。

粪菌移植治疗的不良反应包括嗳气、腹胀、腹痛、呕吐、腹泻、发热和一过性的C-反应蛋白水平升高,但其中大部分症状会在l ~ 2 d内自行缓解[8-12, 21-27]。动物实验发现,粪菌移植治疗存在将供体的病原体传给受体的可能性[30]。在本研究中,患儿4在粪菌移植治疗当天出现短暂的腹泻次数增加,第2天自行缓解。患儿5在粪菌移植治疗当天出现发热,后自行消退,发热是否与粪菌移植治疗相关尚不确定。粪菌移植治疗能在短时间内显著改善RCDI患儿的临床症状,无论是短期还是长期随访,均未发现患儿出现严重的不良反应。

虽然部分临床研究支持开展儿童RCDI粪菌移植治疗,但对粪菌移植治疗的安全性仍需高度关注,因为目前还缺乏粪菌移植治疗的长期安全性数据。儿童是一个特殊群体,粪菌移植治疗儿童RCDI需动态评估其肠道菌群的变化情况并适当调整治疗剂量。从已有的研究报告看,粪菌移植治疗儿童RCDI大多获得了成功,但這仍须得到大样本量的临床随机试验的确认。粪菌移植治疗儿童RCDI的病例选择也须慎重,因为大多数RCDI患儿没有临床症状,现适用患儿应是经抗生素规则治疗无效或复发、且排除了其他疾病引起腹泻等临床症状的RCDI患儿[31-32]。

本研究结果显示,粪菌移植治疗用于儿童RCDI有效、安全且可被耐受。未来还可设计一些临床随机、对照试验来研究粪菌移植治疗其他疾病的临床疗效,并分析治疗前后患者肠道菌群组成的变化。这类研究不仅有利于人们更好地理解粪菌移植治疗的机制,且也有助于了解疾病的发病机制。粪菌移植治疗目前均采用全粪菌移植方法,未来可进一步细化,以所获特定的有益菌或其代谢产物来治疗疾病。至于选择的供体年龄是否应与患者年龄相近,尚待进一步的探讨。

参考文献

[1] Sammons JS, Toltzis P. Recent trends in the epidemiology and treatment of C. difficile infection in children [J]. Curr Opin Pediatr, 2013, 25(1): 116-121.

[2] Wendt JM, Cohen JA, Mu Y, et al. Clostridium difficile infection among children across diverse US geographic locations [J]. Pediatrics, 2014, 133(4): 651-658.

[3] Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections [J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2013, 108(4): 478-498, quiz 499.

[4] Brandt LJ. American Journal of Gastroenterology lecture: intestinal microbiota and the role of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in treatment of C. difficile infection [J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2013, 108(2): 177-185.

[5] Aroniadis OC, Brandt LJ. Fecal microbiota transplantation: past, present and future [J]. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2013, 29(1): 79-84.

[6] Mattner J, Schmidt F, Siegmund B. Faecal microbiota transplantation — a clinical view [J]. Int J Med Microbiol, 2016, 306(5): 310-315.

[7] Drekonja D, Reich J, Gezahegn S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review [J]. Ann Intern Med, 2015, 162(9): 630-638.

[8] Kahn SA, Young S, Rubin DT. Colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in a child [J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012, 107(12): 1930-1931.

[9] Kronman MP, Nielson HJ, Adler AL, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation via nasogastric tube for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in pediatric patients [J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2015, 60(1): 23-26.

[10] Rubin TA, Gessert CE, Aas J, et al. Fecal microbiome transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: report on a case series [J]. Anaerobe, 2013, 19: 22-26.

[11] Russell GH, Kaplan JL, Youngster I, et al. Fecal transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in children with and without inflammatory bowel disease [J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2014, 58(5): 588-592.

[12] Wang J, Xiao Y, Lin K, et al. Pediatric severe pseudomembranous enteritis treated with fecal microbiota transplantation in a 13-month-old infant [J]. Biomed Rep, 2015, 3(2): 173-175.

[13] McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) [J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2018, 66(7): 987-994.

[14] McDonald LC, Owings M, Jernigan DB. Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short-stay hospitals, 1996-2003 [J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2006, 12(3): 409-415.

[15] Sohn S, Climo M, Diekema D, et al. Varying rates of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea at prevention epicenter hospitals [J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2005, 26(8): 676-679.

[16] Lessa FC, Gould CV, McDonald LC. Current status of Clostridium difficile infection epidemiology [J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2012, 55(Suppl 2): S65-S70.

[17] Gupta A, Pardi DS, Baddour LM, et al. Outcomes in children with Clostridium difficile infection: results from a nationwide survey [J]. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf), 2016, 4(4): 293-298.

[18] Brandt LJ, Reddy SS. Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection [J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2011, 45(Suppl): S159-S167.

[19] van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile [J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 368(5): 407-415.

[20] Hourigan SK, Oliva-Hemker M. Fecal microbiota transplantation in children: a brief review [J]. Pediatr Res, 2016, 80(1): 2-6.

[21] Fareed S, Sorode N, Stewart FJ, et al. Applying fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) to treat recurrent Clostridium difficile infections (rCDI) in children [J/OL]. PeerJ, 2018, 6: e4663 [2018-06-01]. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4663.

[22] Hourigan SK, Chen LA, Grigoryan Z, et al. Microbiome changes associated with sustained eradication of Clostridium difficile after single faecal microbiota transplantation in children with and without inflammatory bowel disease [J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2015, 42(6): 741-752.

[23] Kelly CR, Ihunnah C, Fischer M, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection in immunocompromised patients [J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2014, 109(7): 1065-1071.

[24] Pierog A, Mencin A, Reilly NR. Fecal microbiota transplantation in children with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection [J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2014, 33(11): 1198-1200.

[25] Russell G, Kaplan J, Ferraro M, et al. Fecal bacteriotherapy for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection in a child: a proposed treatment protocol [J]. Pediatrics, 2010, 126(1): e239-e242.

[26] Walia R, Garg S, Song Y, et al. Efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in 2 children with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection and its impact on their growth and gut microbiome [J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2014, 59(5): 565-570.

[27] Youngster I, Mahabamunuge J, Systrom HK, et al. Oral, frozen fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) capsules for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection [J/OL]. BMC Med, 2016, 14(1): 134 [2018-04-25]. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0680-9.

[28] Grehan MJ, Borody TJ, Leis SM, et al. Durable alteration of the colonic microbiota by the administration of donor fecal flora [J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2010, 44(8): 551-561.

[29] Khoruts A, Sadowsky MJ. Therapeutic transplantation of the distal gut microbiota [J]. Mucosal Immunol, 2011, 4(1): 4-7.

[30] Quera R, Espinoza R, Estay C, et al. Bacteremia as an adverse event of fecal microbiota transplantation in a patient with Crohns disease and recurrent Clostridium difficile infection[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2014, 8(3): 252-253.

[31] Jangi S, Lamont JT. Asymptomatic colonization by Clostridium difficile in infants: implications for disease in later life [J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2010, 51(1): 2-7.

[32] Schutze GE, Willoughby RE, Committee on Infectious Diseases, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in infants and children [J]. Pediatrics, 2013, 131(1): 196-200.