老年难治性胃食管反流病的临床特征分析

2018-07-09黄婷婷李英男黄启阳杨竞

黄婷婷,李英男,黄启阳,杨竞

胃食管反流病(gastroesophageal reflux disease,GERD)是一种常见的上消化道疾病[1],其发病率在欧美国家为10%~20%[2-3]。有研究表明,在美国有超过40%的成年人每月至少出现1次GERD相关症状,20%每周出现1次[4-5]。在中国,GERD症状的发生率约为12.5%[6]。目前,质子泵抑制剂(PPI)仍然是治疗反流性食管炎最重要的药物。然而,有关研究表明,在每天服用1~2次标准剂量PPI药物的情况下,仍有高达40%的GERD患者症状不能完全缓解或根本无效[7-8],称之为难治性胃食管反流病(refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease,rGERD)。这种情况下,通常会增加PPI剂量或更改治疗方案,但治疗效果仍不尽满意。目前探讨PPI治疗失败原因的研究较多,提出了一些PPI耐药的原因,包括生活方式、服药依从性、食管超敏反应、食管上皮超微结构和功能改变等[8]。作为特殊人群,GERD老年患者的症状不典型,病情更严重,糜烂性食管炎、Barrett食管和食管癌等并发症的发生率更高[9]。本研究旨在分析老年难治性GERD患者的临床特征,以期对治疗提供一定的帮助。

1 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象 选取2015年5月-2017年4月于解放军总医院消化科住院或门诊确诊为GERD的65岁以上老年患者,均接受PPI治疗3个月以上(奥美拉唑20mg,或兰索拉唑30mg,或雷贝拉唑10mg,或泮托拉唑40mg,每日1次或2次)。根据患者对PPI药物的反应情况将其分为有效组和难治组。有效组:服用PPI后GQ量表评分<8分,或较治疗前下降>4分;24h食管pH监测结果为阴性;内镜下提示反流性食管炎消失,或分级降低1级或1级以上。未能达到有效组标准的患者纳入难治组。GERD的诊断标准(参照中国胃食管反流病共识意见)包括:GQ量表评分≥8分;24h食管pH监测结果为阳性;胃镜提示反流性食管炎。

1.2 纳入及排除标准 纳入标准:年龄≥65岁;符合GERD的诊断标准;签署知情同意书。排除标准:合并其他消化性溃疡、贲门失弛缓、卓艾综合征等上消化道疾病;消化道肿瘤及药物性食管炎患者;其他内科严重疾病而致意识不清者;精神病患者;无法完成问卷调查。

1.3 一般资料 包括患者姓名、性别、年龄、体重、身高、体重指数(BMI)、婚姻状况(已婚,离婚或丧偶)、目前是否吸烟和饮酒、既往疾病史[有无高血压、糖尿病、慢性阻塞性肺疾病(chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,COPD)、缺血性心脏病、肾衰竭、抑郁症、幽门螺旋杆菌感染、哮喘等],用药情况,与GERD有关的症状(反酸、胃灼热、胸痛、上腹痛、咳嗽、睡眠障碍、腹胀和吞咽困难等)。在PPI治疗前后分别填写GQ调查问卷,得分≥8分诊断为胃食管反流病。食管24h pH监测:DeMeester评分>14.72分诊断为胃食管反流病。内镜检查反流性食管炎的严重程度及有无食管裂孔疝。

1.4 统计学处理 采用SPSS 23.0软件进行统计分析。计量资料以±s表示,符合正态分布时采用独立样本t检验,不符合正态分布时采用秩和检验。计数资料用率(%)表示,单因素分析采用χ2检验,多因素分析采用logistic回归分析。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 一般资料 共招募319例GERD老年患者,46例失访,最终共纳入273例,其中有效组192例,难治组81例。男176例,女97例,年龄72.6±7.5岁。两组患者年龄、性别、吸烟和饮酒比例等差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。难治组BMI明显高于有效组,婚姻状况方面,难治组丧偶比例明显高于有效组,而已婚比例明显低于有效组(P<0.05,表1)。

表1 两组老年难治性胃食管反流病患者一般资料比较Tab.1 Comparison of general data between two groups

2.2 基础疾病及用药情况 难治组糖尿病患者中的抑郁症患者比例明显高于有效组,而高血压、COPD、缺血性心脏病、肾衰竭、幽门螺杆菌感染、哮喘患者等的比例在两组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。用药方面,难治组服用钙通道拮抗剂和苯二氮类药物的患者多于有效组(P<0.05),而服用硝酸酯类药物、阿司匹林和氯吡格雷的患者比例差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表2)。

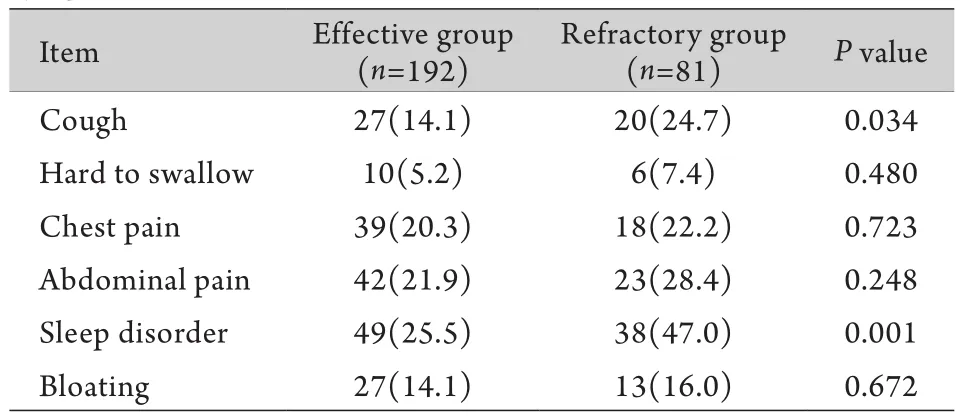

2.3 不典型GERD症状 难治组有咳嗽症状、睡眠障碍的患者比例高于有效组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。而吞咽困难、胸痛、上腹痛、腹胀等症状在两组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表3)。

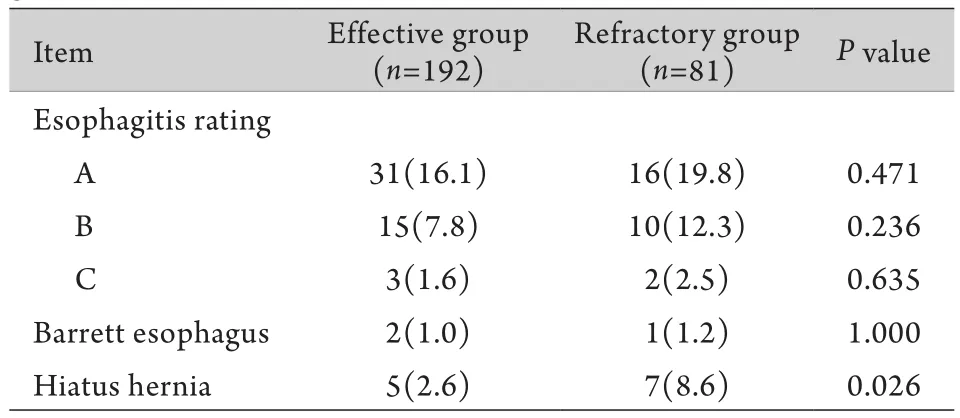

2.4 内镜表现 有效组裂孔疝发病率明显低于难治组(P=0.026)。两组患者胃镜下均未发现D级反流性食管炎患者(洛杉矶分级)。两组患者内镜下食管炎症分级差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表4)。

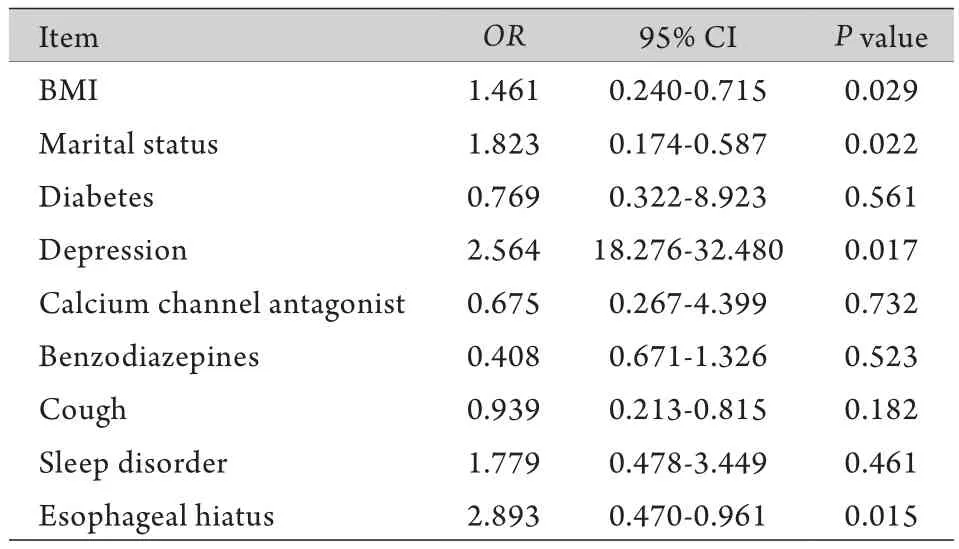

2.5 Logistic回归分析 将上述有统计学差异的因素纳入logistic回归分析,结果显示,BMI、食管裂孔疝和抑郁症可增加PPI治疗失败的风险。此外,婚姻状况也是决定PPI治疗是否有效的重要因素,丧偶的GERD患者发生PPI治疗失败的风险更高。而高血压、糖尿病、是否服用钙通道阻滞剂或苯二氮类药物、睡眠障碍、食管炎内镜下分级等不是PPI治疗失败的危险因素(表5)。

表2 两组老年难治性胃食管反流病患者基础疾病及用药情况比较[例(%)]Tab. 2 Comparison of basic illness and medication in two groups [n(%)]

表3 两组不典型GERD胃食管反流症状的比较[例(%)]Tab.3 Comparison between two groups of patients with atypical symptoms of GERD [n(%)]

表4 两组老年难治性胃食管反流病患者内镜下表现比较[例(%)]Tab.4 Comparison of endoscopic performance between two groups [n(%)]

表5 PPI治疗失败危险因素的logistic回归分析Tab.5 Logistic multivariate regression analysis of risk factors for failed PPI treatment

3 讨 论

GERD是指胃内容物反流引起不适症状和(或)并发症的一种疾病,其典型的症状是胃灼热和反酸,抑酸治疗特别是PPI是控制症状和治疗GERD最有效的药物,但仍有约40%的GERD患者对足量PPI治疗反应不佳,即rGERD。2016年《亚太地区胃食管反流病的处理共识》将rGERD定义为:经标准剂量PPI治疗8周后,典型的症状(胃灼热、反酸)仅部分缓解或完全无缓解[10]。多种因素与rGERD的发生有关[11]。有研究显示,肥胖患者比正常人更容易发生食管酸暴露[12-14]。下食管括约肌功能缺陷在高BMI患者中更为常见,而肥胖患者食管下括约肌功能缺陷的发生率是正常体重患者的2倍[13]。此外,肥胖还可以改变抑酸药物的药代动力学,包括药物分布、代谢和清除,从而影响药物的效果[15-17]。本研究结果显示,高BMI患者容易出现PPI治疗失败。

近10年来有充分证据表明心理因素与胃肠疾病有关[18]。本研究表明,抑郁症与GERD患者的PPI治疗效果有关,难治组有4例抑郁症患者,而有效组仅有1名抑郁症患者,提示心理状态和精神压力在GERD患者的治疗中发挥了重要作用。抑郁症患者可能会变得高度敏感,能够过度感知酸反流引起的不适症状,而这些不适症状又进一步导致情绪恶化和心理压力的增加,从而造成恶性循环[18]。

此外,我们还观察到食管裂孔疝是老年GERD患者PPI治疗失败的一个重要原因。食管裂孔疝能够影响食管下括约肌的功能,并使远端食管的酸廓清功能下降[3,19]。食管裂孔疝的患病率随着年龄的增长而增加[20],因此有很多老年GERD患者都同时患有食管裂孔疝。

本研究还发现,影响PPI治疗效果的另一个重要因素是婚姻状况。丧偶的患者更易发生PPI治疗失败,这可能与独身老人的治疗依从性较差有关。离异或丧偶的患者通常缺乏亲人或朋友的照顾,加上老年人生活自理能力差、记忆力减退导致生活质量低下,服药依从性明显下降。此外,孤独老人的抑郁、恐惧、悲观等情绪所带来的心理问题也会导致PPI的失败。因此,重视老年GERD患者的心理健康更加不可忽视。

老年rGERD患者常因反酸、胃灼热、咳嗽及睡眠障碍等症状反复就诊,治疗上通常会增加PPI剂量或更改治疗方案,但效果仍不尽满意。本研究结果提示多种因素与老年人rGERD的发生有关,须得到重视并积极治疗[5]。

[1] Wang XX, Liu BY, Wang GQ. Recurrent Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease caused by Gastroesophageal reflux disease:a case report[J]. Chin J Pract Intern Med, 2016, 36(S2): 120-122.[王秀秀, 刘宝义, 王光强. 胃食管反流病致慢性阻塞性肺疾病反复发作1例[J]. 中国实用内科杂志, 2016, 36(S2): 120-122.]

[2] Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus paper[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2006,101(8): 1900-1920.

[3] Liu Q, Wu Y, Wang ES, et al. Clinical features of gastroesphageal reflux disease in the elderly[J]. Geriatr Health Care, 2013,19(2): 86-88. [刘青, 吴英, 王二嫂, 等. 老年胃食管反流病临床特征的研究[J]. 老年医学与保健, 2013, 19(2): 86-88.]

[4] Fass R, Fennerty M, Vakil N. Nonerosive reflux diseasecurrent concepts and dilemmas[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2001,96(2):303-314.

[5] Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, et al. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota[J]. Gastroenterology, 1997,112(5): 1448-1456.

[6] Qu KP, Cheng XZ. Meta analysis of the prevalence of gastroesphageal reflux disease in parts of China[J]. Chin J Gastroesophagol Reflux Dis (Electron Ed), 2015, 2(1): 34-44.[屈坤鹏, 成晓舟. 我国部分地区胃食管反流病患病率的meta分析[J]. 中华胃食管反流病电子杂志, 2015, 2(1): 34-44.]

[7] Scarpellini E, Ang D, Pauwels A, et al. Managementof refractory typical GERD symptoms[J]. Nat Rev GastroenterolHepatol,2016, 13(5): 281-294.

[8] Cicala M, Emerenziani S, Guarino MP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor resistance, the real challenge in gastro-esophageal reflux disease[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2013, 19(39): 6529-6535.

[9] Jin Y, Liu QM, Yan WF, et al. Diagnostic value of combined esophageal multi-channel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring for gastroesophageal reflux in critically ill patients[J]. Med J Chin PLA, 2016, 41(5): 412-415. [金一, 刘秋旻, 颜卫峰, 等. 多腔道阻抗联合pH监测对危重症患者胃食管反流的诊断价值研究[J]. 解放军医学杂志, 2016, 41(5):412-415.]

[10] Fock KM, Talley N, Goh KL, et al. Asia·Pacific consensus on the managementofgastro-oesophageal reflux disease:anupdatefocusingon refractory refluxdiseaseand Barrett's oesophagus[J]. Gut, 2016, 65 (9): 1402-1415.

[11] Chen J, Xu JY, Xie XP, et al. Cause analyses of refractory GERD patients[J]. Chin J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2002, 11(4): 358-360. [陈婕, 许军英, 谢小平, 等. GERD治疗失败病因研究[J].胃肠病学和肝病学杂志, 2002, 11(4): 358-360.]

[12] El-Serag HB, Ergun GA, Pandolfino J, et al. Obesity increases oesophageal acid exposure[J]. Gut, 2007, 56(6): 749-755.

[13] Ayazi S, Hagen JA, Chan LS, et al. Obesity and gastroesophageal reflux: quantifying the association between body mass index,esophageal acid exposure, and lower esophageal sphincter status in a large series of patients with reflux symptoms[J]. J Gastrointest Surg, 2009, 13(8): 1440-1447.

[14] Crowell MD, Bradley A, Hansel S, et al. Obesity is associated with increased 48-hours esophageal acid exposure in patients with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2009, 104(3): 553-559.

[15] Blouin RA, Warren GW. Pharmacokinetic considerations in obesity[J]. J Pharm Sci, 1999, 88(1): 1-7.

[16] Jacobson BC. Body mass index and the efficacy of acidmediating agents for GERD[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2008, 53(9): 2313-2317.

[17] Barak N, Ehrenpreis ED, Harrison JR, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in obesity: pathophysiological and therapeutic considerations[J]. Obes Rev, 2002, 3(1): 9-15.

[18] Van der Velden AW, De Wit NJ, Quartero AO, et al. Maintenance treatment for GERD: residual symptoms are associated with psychological distress[J]. Digestion, 2008, 77(3-4): 207-213.

[19] Huang X, Zhu HM, Deng CZ, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux:the features in elderly patients[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 1999,5(5): 421-423.

[20] Amano K, Adachi K, Katsube T, et al. Role of hiatus hernia and gastric mucosal atrophy in the development of reflux esophagitis in the elderly[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2001, 16(2): 132-136.