城中村浅记

——维尔纽斯施纳皮施克斯木屋街区

2018-06-19叶卡捷琳娜拉韦尼克JekaterinaLavrinec

叶卡捷琳娜·拉韦尼克/Jekaterina Lavrinec

黄华青 译/Translated by HUANG Huaqing

城市叙事:“增长城市”vs“收缩区域”

隐喻和叙事在城市发展中发挥着重要作用,因为它们塑造了城市生活的目标和轨迹。“增长城市”的话语在现代化及市场经济开发时期都很普遍。对维尔纽斯来说,近几十年来它都呈现为一座“绿色之城”,直到最近的官方话语中才开始强调持续增长的理念(“维尔纽斯是一座增长城市”)——也就是2016年提出,将提升城市中心密度的目标作为未来城市发展战略之一。基于“增长城市”理念的话语盛行,标志着高强度投资、建造的时代来临,同时在很多情况下,也伴随着那些对社区而言极为珍贵的空间和路线的丧失。

实际上,“增长城市”理念早已影响了维尔纽斯多个历史阶段的发展。在苏联推动的现代化时期它就已得到彰显。施纳皮施克斯木屋街区是19世纪末至20世纪初的一批木结构房屋“群落”,它们经历1860-1870年代涅里斯河右岸的城市化进程后幸存至今。当时,尽管街区化住宅和这一木屋区之间差别显著,但城市与乡村生活方式的共存依然成为维尔纽斯城市生活的有机组成部分。几户小木屋间会有共享的花园,用以种植水果、蔬菜,饲养家畜家禽。这里的邻里关系比起那些住宅楼街区中的要亲密、开放得多。紧邻木屋街区有一处传统集市,它曾经是(某种程度上依然是)各地居民的热门目的地,也是该区域城乡居民之间沟通交流的场所。对于维尔纽斯市民而言,城市各地的城中村大部分皆被视为过去城乡结构的独特原型,是历史留下的印记。

1992年,施纳皮施克斯木屋街区部分被列入文化遗产名录,因其建筑、民族文化和城市品质的价值而受到保护[1]。街区的其余部分依然可以开发,但设定了一片限定建筑物高度的缓冲区。由于缺乏对于未来发展的具体设想,当地居民被动地空等了十余年。这种状态往往导致城市区的衰败,而根据规则,需要积极主动的调解者和领导者,将当地居民聚在一起,共同规划街区的未来设想。由于没有强有力的社区组织,这个街区在缺乏明确价值、形象和未来的情况下陷入收缩。

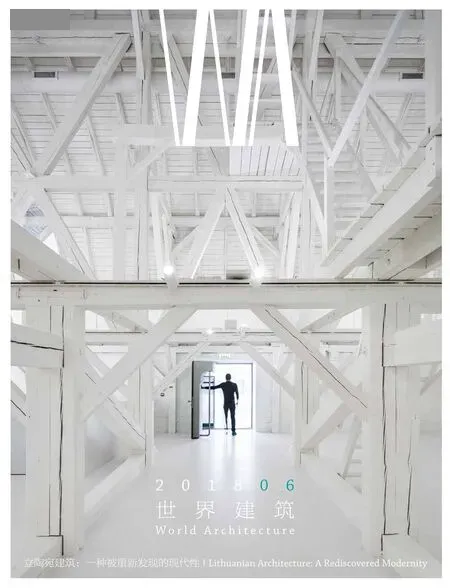

1 施纳皮施克斯木屋街区/ Wooden Šnipiškės Neighbourhood

城中村的乡村生活方式被边缘化的开端是在21世纪初,该区域开启了一系列高强度、市场主导的再开发项目。在社交媒体中出现一批信息,谈到所谓“木房子的懒主人”居住的“脏地方”“罪犯窟”,指的就是施纳皮施克斯木屋街区。而在城市中饲养家畜家禽的做法,同样引来负面的关注和嘲讽,最终在城中村中被禁止。对这个街区负面形象的不负责任的传播,给当地居民造成了极其深刻的创伤:我们城市游戏与研究实验室发现,当地的孩子常常对学校同学隐藏其家庭地址,以避免遭到欺凌。木屋街区的负面形象与商务区的成功形象之间的割裂,传达出一种社会与经济分化的趋势,加重了历史街区居民和办公楼白领间的隔阂。就像弗兰·东斯在她的研究《城市设计:城市形态的社会生活》中所言,“无论城市是被视为领域,还是沟通的网络,城市的空间及物质组织对于其社会体验及未来愿景而言皆十分关键。”[2]

一片超高层建筑构成的商务区,将涅里斯河右岸变成了所谓“玻璃山丘”,有人甚至将这片高速增长的商务区称为“第二个曼哈顿”。由于功能性单一、对于其他社会群体来说消费过于昂贵,这个商务区在下班后和节假日就成了无人的“鬼城”,咖啡馆关门,商店空空如也。商务区开发中最缺乏的就是多样性。在我们看来,商务区白领和历史老城居民的对话对于两个区域的宜居性皆意义非凡。我们应探讨如何让各个区域都向另一个区域的使用者“开放”。不过这类“对话导向的思维”,必须在商务区开发项目中付诸实践才有意义。

哈维·莫洛奇在他的经典文章《城市作为增长机器:走向空间的政治经济学》中指出一个重要问题:谁才是决定城市生活形态的主导叙事的生产者和受益者[3]。他提出,尽管城市增长的主导叙事对精英阶层而言十分受用,但同样存在替代性的地方(“反增长”)叙事,源自那些城市激进主义者、中产阶级职业者和工人。在我们看来,关注弱势地区居民的微小地方叙事,是社区建设工作的重要部分,也是对历史街区采取一种敏感、包容性开发的第一步。

2 城市修补对比/Urban contrast of patchwork

包容性实践:街区变迁中的小故事

人们通过一些小故事及各类物件与他们所在的街区建立关联。有些可能在观察者眼中微不足道,但对于当地几代居民来说却至关重要。为了建立街区包容性开发的前提,Laimikis团队试图挖掘那些支撑着地方认同的地方性叙事。在空间中标定出街区关键的位置、物件和故事,为设计团队提供了在制定空间开发策略时可借鉴的宝贵洞察。

地方知识中出现的一些物件,指向不同的历史片层,尽管今天有些已经不复存在,但它们依然强有力地影响着地方认同。简单列举几个施纳皮施克斯居民在展示自己的街区时提到的元素:古老的石板路,如今依然部分保存在街区中;维尔纽斯出租马车车夫的马和车(今天在这里还可以看到马蹄铁);有些居民骄傲地说,他们住在一栋曾是马厩的漂亮房子里;有些居民依然记得粘土开采场的位置,这就联想到这里曾在16~17世纪因陶瓷作坊而闻名的历史,当时维尔纽斯老城的屋瓦皆产于此;街区中有些地方的下水系统还未现代化,街上的蓝色立管也成了场所视觉认同的一部分。像这些微小片段,是郊区地方性叙事的一部分,它曾对城市很重要,也有它自己的生活方式。然而,这些19世纪荣耀历史留下的线索,皆在20世纪初“贫民窟”的主导叙事下被埋葬了。

必须承认,在今天的施纳皮施克斯木屋街区,与这段历史的联系已越发微弱。原因是它在二战期间经历了一段剧烈的人口变化时期,很多房屋主人被迫放弃自己的房产,他们的房子后来被新搬来的家庭瓜分为临时住所。然而,今天有很多居民在积极收集街区历史的信息,有些甚至与之前的房主取得联系。战后时期,这个街区还得到了一个流行外号——“小上海”,这似乎是全球犯罪团伙对于那些由非法居民自发占据并开发的聚落的称号。

为了收集并活化街区中的小故事,Laimikis团队采取了参与性艺术方法。在公共空间举办的文化活动、街区中的艺术装置、城市游戏和游行,都给街区居民带来频繁的会面、分享故事和理念的机会。此外,这些活动亦有利于激发地方性叙事,重塑街区的负面形象[4]。举几个例子,我们团队在2015年为变化中的街区创造了一个叫做“Urbingo”的城市游戏,它不仅可用于收集街区故事,也建立了一个频繁使用的图像和文字档案库。这个卡牌游戏(如今也有电子版)激发使用者积极探索街区的元素、全景和故事,由此让街区向游客“敞开”,揭示场所的文化和建筑价值。第一版游戏就是为变迁中的施纳皮施克斯木屋街区创造的(如今我们也为越来越多的其他欧洲城市街区创建Urbingo的特殊版本)。这个游戏中很重要的部分是,当地人通过为游戏卡提供物件和故事主题而参与到游戏创造中。对于当地人来说,这个游戏提供了一个让他们重新审视生活环境、并选取那些希望与参观者共享之物的契机。这一任务塑造了一种看待生活环境的创造性态度,促进当地居民更专注地观察街区的细节和全景。这个游戏吸引了来自城市各个地区的参与者,很多人都是第一次参观施纳皮施克斯木屋街区,这积极促进了场所负面形象的重塑。此外,这个游戏也帮助我们监控街区的高速发展、感受它的脆弱(原因是街区高强度开发的全景图始终剧烈变化着)。

还有一种展现场所的历史文脉和文化潜能的包容性活动,即Laimikis团队与当地居民在2013-2015年合作举办的“街道马赛克工作坊”。鉴于施纳皮施克斯街区在16-17世纪曾因陶瓷作坊而闻名的事实,我们提议当地居民使用简单的马赛克技艺装饰街区中的老旧电线杆。在露天制作马赛克的过程中,当地居民间建立了交流和联系,很多人都通过捐赠陶瓷、提供创意的方式予以帮助。这种通过参与手工艺活动而激发协同感的做法,呼应了理查德·桑内特在他的研究《在一起:合作的仪式、愉悦与政治》中提出的洞见:将合作视为一种技艺,以及社会合作式工作坊的重要性[5]。“街道马赛克工作坊”作为一项开放的、仍在进行的活动,帮助他们在街区中建立起一张互助与信任之网。一年之内,由于当地居民(尤其是儿童)的积极参与,街区中出现了一条马赛克线路。这鼓励一些居民开始在街区中运营另类的导游线路。在我们的经验中,空间针灸疗法(小干预、大变化)是街区和公共空间复兴的有效方式。通过激活历史情景,这种包容性的创造活动有利于场所形象的重塑[6]。在前面提到的例子中,Laimikis扮演了文化调解者的角色,根据街区的问题和需求提出活动模式,但真正创造活动内容的是居民本身。

Urban narratives: "growing cities" vs. "shrinking areas"

Metaphors and narratives play important role in urban development, as they shape the priorities and trajectories of city life. The narratives of the "growing city" were common for the period of modernisation and for market-oriented development. For Vilnius, which has presented itself for decades as a "green city", the idea of constant growth ("Vilnius is a growing city") has become central in the official communication just recently, after the goal of raising the density in the city centre was proclaimed in 2016 as a city strategy for the next years.Rhetoric based on the concept of the growing city marks the period of intensive investments, constructions and in many cases – loss of places and routes dear to groups of residents.

However, the idea of "growing city" was present in different phases of Vilnius development. It was implemented in the process of Soviet modernisation. The wooden neighbourhood of Šnipiškės is a conglomeration of a few "islands" of the wooden architecture built in the end of the 19th and the beginning of 20th centuries,that survived the urbanisation of the right bank of the Neris river in Vilnius, in the 60's-70's. Back then, despite the difference between the quarters of block houses and the wooden area, a co-existence of the urban and rural lifestyles became an organic part of Vilnius life. Wooden houses with the gardens, shared between several families each, provided conditions for growing fruits and vegetables and keeping domestic animals. The relations between the neighbours in this area were more intensive and open than between the neighbours in the blocks of flats. Next to the wooden neighbourhood there is a traditional market place, which used to be (and still is to some extent) a point of attraction for various groups of residents; it used to be a place where a contact between the residents of urban and rural parts of the district took place. From the perspective of Vilnius residents, the urban villages in various parts of Vilnius were mostly seen as peculiar rudiments of the previous urban-rural structure, a mark of the past times.

In 1992 a part of the wooden Šnipiškės neighbourhood was included in the cultural heritage register as protected heritage area (referred as "Skansen"), valuable for its architectural, ethnic cultural, and urban qualities[1].Other parts of the wooden area remained open for the redevelopment, although a buffer zone, limiting the height of the possible constructions, was set. A lack of detailed scenario for the further vision for this area left the residents in passive waiting for decades. This state usually brings decay to the urban areas, and as a rule, needs pro-active mediators and active leadership to bring residents together for co-developing a shared vision for the neighbourhood.With no strong community, the neighbourhood turns into a shrinking area which lacks articulated values, image, and future.

A tendentious marginalisation of the rural lifestyle of the urban village started in the beginning of the 21st century, when an intensive market-oriented redevelopment of the area has begun. A number of messages in mass-media about the "dirty place","criminal slums" with "lazy owners of the wooden houses", referring to the wooden area of Šnipiškės, was growing in mass media. The fact of keeping the domestic animals in the city attracted negative attention and mockery, and was forbidden in the urban village. The consequences of the irresponsible communication of the negative image of the neighbourhood are deeply traumatic for the residents: our urban games and research Lab has found that the kids of the area used to hide their home addresses from their classmates at school, seeking to avoid the bullying. A split between the negative image of the wooden area and the image of successful business area expresses the attitude towards the social and economic contrast and enlarged the distance between the residents of the historic area and the office workers. As Fran Tonkiss puts it in her study Cities by Design: The Social Life of Urban Form,"whether the city is conceived in terms of territory,however, or as networks of connection, the spatial and the physical organisation of the urban is critical to its social experience and its future prospects"[2].

A development of the business area of skyscrapers turned the right bank of the Neris river into so-called"glass hill", some referred to the growing business district as to the "second Manhattan". With no variety of functions (mixed-use), and with no affordable places for people of different social groups, this business part of the area turns into a "ghost area" with no people around after the working hours and in the weekends,with closed cafes and empty shops. Variety is what was missed in the development of this business area. From our perspective, the dialogue between people, working in the business area and living in the historical area is crucial for the liveability of the both parts of the district.We need to model how to "open" each of the parts to the users from different parts. But this kind of "dialogueoriented thinking" must be implemented into the development projects of the business area.

In his classical paper "The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place" Harvey Molotch pointed out the importance of the question,who is a producer and benefiter of the dominating narrative, that shapes the urban life. He argued that while the dominating narrative of urban growth serves well to the elites, there are alternative local ("antigrowth") narratives, produced by groups of urban activists, middle-class professionals and workers[3].From our perspective, this focus on the small local narratives by the residents of disadvantaged areas is an important part of community work as the very first step in sensitive inclusive development of the historic areas.

Inclusive practices: small stories in the changing neighbourhood

People relate themselves to the neighbourhoods through small stories and various objects. Some of them might seem insignificant for the observer, but are extremely important for several generations of the residents. To arrange conditions for inclusive development of the neighbourhoods, Laimikis team seeks to identify the local narratives, crucial for identity of the place. Mapping of the key localities, objects, and stories of the neighbourhoods provides valuable insights to draw upon while developing spatial solutions for the neighbourhood.

Objects, present in the local knowledge, refer to different historical layers, and some might be physically absent but still powerful for the local identity. Just to mention few elements that Šnipiškės residents refer to while presenting their neighbourhood: the historical pavement, which is still partly present in the neighbourhood. The horses and cabins of Vilnius cab drivers (nowadays you still can find horseshoes here).Some residents say proudly that they live in the nice house which used to be a horse stable. Some remember the location of the quarries for extraction of clay, and this relates to the historical fact, that this neighbourhood was famous for its ceramic workshops in 16th-17th centuries,and the shingles for the roofs of the Old Town of Vilnius were produced here. The sewing system in some parts of the neighbourhood still remains unmodernised, however,street standpipe of blue colour became a part of visual identity of this place. Small episodes like these are a part of local narrative of suburbia that used to be important for the city and had its own way of life. But these connections to the proud past of 19th century were buried under the dominating narrative of "slums" in the beginning of the 20th century.

It must be said, that a possibility to relate to the neighbourhood's history is limited in the wooden Šnipiškės neighbourhood, which faced a dramatic population shift during the WWII, when the owners of many houses were forced to abandon their property.The houses were divided between the new families who moved to the wooden neighbourhood as to a temporal shelter. However, nowadays some residents are active in collecting the facts about the history of the neighbourhood and some even hold occasional contact with the previous owners. It is in the postwar period when the historical neighbourhood has gained its alternative popular name, Shanghai, which appeared to be a common name in the criminal slang for the settlements all around the world, which were taken and developed by the residents groups illegally, in spontaneous way.

城市修补:城中村的脆弱

人们不仅通过这些故事与故乡建立关联,还借助建造、固定、装饰生活环境来建立情感联系。木屋和基础设施都需要居民的悉心照料。“修补”只是其中一种延长物件寿命的策略。尽管那些处于遗产保护区的住宅在翻新时受到诸多限制,但对于其他未列入遗产名录的小建筑和住宅,屋主可采用各种材料(金属、塑料、木材)进行修补。一幅幅层次丰富的独特天然拼贴画就此诞生。在不断追求增长和翻新的当代城市中,历史修补留下的真实表皮成了一个珍贵的视觉和触觉愉悦之源。

反过来说,这个区域也通过引入新的城市片层、拆除旧有城市肌理来进行“修补”。开发项目嵌入了截然相反的建筑形式、材料(木材、混凝土和玻璃)及日常节奏(由工作日午休和下班构成的办公节奏,以及当地居民的缓慢生活节奏)。每种材料(木材、混凝土和玻璃)都有不同的生命周期以及不同的翻新方法。

我们发现,修补的隐喻对于这个街区非常重要,因为在城市再开发的中心清晰呈现城中村特征是很有意义的:它的脆弱、历史片层的共存、城中村内部的开放社交生活、将手工艺作为一套独特技艺,在当代社会都十分难得。Laimikis将这个施纳皮施克斯街区的设计概念及相关材料,呈现于2017/2018深圳城市建筑双城双年展的城中村板块“城市共生”。我们将从中欧城中村之间找到的内在相似点展现于此。在双年展的策展宣言中,侯瀚如、刘晓都和孟岩提出将城中村作为“城市另类新生活的孵化器”。在他们看来,“城中村,作为当代城市另类模式,以特殊的方式体现着城市长期演变的未完成状态。它自身在被外力逼迫下,自发形成并可持续演进。自我繁殖和自我更新是它的立命之本……城中村处于传统与现代之间、清晰与混沌之间、合法与非法之间,在非黑即白的价值评判体系之外,城中村的意义恰恰在于因其所处的灰色地带而被保育和发展出蓬勃的、自下而上的自发潜力。”[7]

城中村本身就是一种脆弱的现象,它质疑着城市不同历史阶段的大规模开发轨道。它丰富了城市生活,拓展着空间和生活方式的多样性;它包含着关联过去的素材和叙事以及未来的全部潜力,理应抱着关注与关怀重新审视。□

3 电线杆上的马赛克/ Mosaics(1-3图片来源/Sources: 作者提供/Provided by author)

参考文献/References

[1]立陶宛文化遗产名录中,关于斯堪森地区施纳皮施克斯木屋的描述/Lithuanian Cultural Heritage Register, description of Skansen territory in Šnipiškės:https://bit.ly/2H18eXc (last visit: April 2018).

[2]弗兰·东斯. 城市设计:城市形态的社会生活. 剑桥大学:政体出版社,2013/Tonkiss G. 2013. Cities by Design. The Social Life of Urban Form. Cambridge:Polity Press:28.

[3]哈维·莫洛奇. 城市作为增长机器:走向空间的政治经济学. 美国社会学期刊,总第82期,下册/Molotch, H. 1976. The City as a Growth Machine:Toward a Political Economy of Place // American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 82, No. 2:309-332.

[4]Kaisari-Ernst, T., Lavrinec, J., Niggemeier K. 2013.Community and neighbourhood development: informal communication tools and cases. Vilnius: Laimikis.LT

[5]理查德·桑内. 在一起:合作的仪式、愉悦与政治,伦敦:企鹅丛书/Sennett, R. 2013. Together. The Rituals, Pleasures & Politics of Cooperation. London:Penguin Books.

[6]叶卡捷琳娜·拉韦尼克. 社区艺术活动作为参与式研究的一种形式:街头马赛克工作室的案例,2014/Lavrinec, J. 2014. Community Arts Initiatives as a Form for Participatory Research: the Case of Street Mosaic Workshop // Creativity Studies, Vol. 7, Issue 1:52-65

[7]侯瀚如,刘晓都,孟言. 城市共生,深港城市/建筑双城双年展/Hou Hanru, Liu Xiaodu, and Meng Yan. Cities, Grow in Difference: Starting from Urban Villages… // Cities Grow in Difference. Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism Architecture, NYC: Sure Design:51-52.

To collect and activate small stories of the neighbourhoods, Laimikis team uses participatory arts approach. Cultural events and actions in public spaces,artistic interventions, urban games and excursions in the neighbourhood provide frequent occasions for people of the neighbourhood to meet and to share their stories and ideas. Furthermore, these forms of activity are used for activating local narratives and for reshaping negative image of the neighbourhood[4].To mention a couple of examples of this approach, an urban game "Urbingo" that our team created in 2015 for the changing neighbourhoods, serves both as a matrix for collecting stories of the neighbourhood, and as an actively used archive of the images and stories. This card game (which also has its electronic version) encourages the users to explore the elements, panoramas, and stories of the neighbourhoods and in this way "opens up" the neighbourhood for the visitors and reveals the cultural and architectural values of the place. The very first version of this game was created for the changing Šnipiškės neighbourhood (and now the number of the neighbourhoods in European cities, for which special Urbingo versions are created, is growing). The important part is that locals contribute to the creation of the Urbingo game by proposing objects and stories for the game's cards. For locals, the game serves as an occasion to re-examine their environment and to pick up things that they want to share with the visitors of the place. This kind of tasks brings creative attitude toward the living environment, promotes an attentive approach to its details and panoramas. This game attracts participants from different parts of the city, many of whom visit the wooden Šnipiškės for the first time,and it helps lot in reshaping the negative image of the place. Additionally, this game helps to monitor the rapid changes of the place and to experience its fragility (due to the intensive redevelopment panorama of the place changes intensively).

A different type of inclusive activity that reveals historical context and cultural potential of the place is a Street Mosaic Workshop that Laimikis launched in cooperation with the local residents in 2013-2015.Drawing upon the fact that Šnipiškės neighbourhood was famous for its ceramic workshops in 16th-17th centuries we proposed to local residents to start decorating old electric poles in the neighbourhood by using simple mosaic technique. While spending time in the open air making the mosaics, lots of contacts between the residents were made, and many people provided their help, donations of the ceramics, and inspirations to the process. This effect of togetherness through shared craft activity corresponds to the insights that Richard Sennett develops in his study "Together.:the rituals, pleasure & politics of cooperation"[5], where he speaks about the cooperation as a craft and point out the importance of the workshops of social cooperation.Street Mosaic Workshop as an open on-going activity helped to build a network of mutual help and trust in the neighbourhood. In a year a mosaic route within the neighbourhood emerged due to the active participation of the residents (especially for kids). It encouraged some residents to start running alternative guide tours to the neighbourhood. In our experience, spatial acupuncture(small intervention – larger scale changes) appears to be effective method in revitalisation of the neighbourhoods and public spaces. By activating the historical scenario,inclusive creative activities contribute to the reshaping the image of the place[6]. In the cases mentioned above,Laimikis plays the role of cultural mediator, proposing formats for activities, depending upon the challenges and needs of the neighbourhood, but it is the residents who create the content of the activities.

Urban patchworks: the fragility of the urban villages

It is not only stories that people relate themselves to the place they live, they also develop emotional connections through building, fixing and decorating the environment. The wooden houses and the infrastructure need much attention from the residents.

Patching is one of the tactics to prolong the life of the objects. While there are limitations for renewing the houses that are located in the protected heritage area, small architecture and the houses that are not included into the cultural heritage list are patched by their owners, using various materials (metal, plastic,wood). In this way, peculiar natural collages of multiple layers are being created. In the contemporary cities with the ambitions for growth and permanent renovation old patched authentic surfaces become a source of rare visual and tactile pleasure.

In its turn, the area itself is being "patched" by introducing new urban layers and by deconstructing previous urban fabric. The redevelopment brings contrast of architectural forms, materials (wood,concrete, glass) and everyday rhythms (office time with its fixed lunch breaks and end of the working days - and slow rhythm of the residents). Each of these materials(wood, concrete, glass) has different circle of life and different approaches toward renewal.

We find the metaphor of patching crucial to this area, as it is instrumental in articulating special characteristics of the urban village in the epicentre of the redeveloped area: its fragility, a coexistence of historical layers, open social contacts within the urban village, and craftsmanship as a set of unique skills, rare in contemporary societies. Laimikis presented this concept and the materials devoted to the Šnipiškės neighbourhood at Bi-city Biennale of Urbanism Architecture in Shenzhen, 2017/2018, within the Urban Village section, subtitled "Hybridity and Coexistence". We found genetic similarities between the urban villages (from China and Europe), presented there. In their curatorial statement for the Biennale,Hou Hanru, Liu Xiaodu, and Meng Yan propose to examine urban villages as "the incubator of alternative new life in a city". According to them, "Urban village, an alternative model of the contemporary city, manifests the ongoing status of the evolution of a city in a unique way. Under the pressure of external forces, it is forming spontaneously and evolving continuously, steered by its own self-reproduction and self-regeneration. […]Residing in between past and present, order and chaos,legal and illegal statuses, and outside the all-or-none system of value judgement, the urban villages valuable for the bottom-up spontaneous potential preserved and developed from the gray zones where they are located"[7].

The urban village itself is a fragile phenomenon which questions the trajectories of massive urban development, implemented in the cities in different periods of time. It enriches the city life, expanding the variety spaces and life styles, it contains material and narrative connections to the past and full of potential for the future, which needs to be re-examined with attention and care.□