立陶宛的现代性:探寻身份认同之路

2018-03-23张利ZHANGLi

张利/ZHANG Li

在高度全球化的21世纪世界中,越来越多的国家不愿认真面对身份认同问题,立陶宛是少数例外之一。今天,众所周知,身份认同是一个令人困扰的主题,特别是存在政治上的风险。那么,明明可以安心地在互联网上传递为普罗大众所喜闻乐见的内容,为什么还要再固执地在学术上去尝试重新梳理有争议的历史进程?立陶宛人对此的回答是明白无误的:因为这是必须的,因为这是我们之所以成为我们的原因。

当一个小国处于周边强国区域影响力的边际交集之下时,是无法拥有地缘政治的安全感的。但是,这样一个国家常常同时受益于丰富和动人的文化交融。立陶宛就是这样一个例子。在过去的一个多世纪里,立陶宛一直在试图解决多重因素交织在一起的身份认同难题,其中包括欧洲传统的纠葛、苏维埃时代的记忆和重新建立的波罗的海独立国家的期许。然而,正是这一充满焦虑的探寻过程,赋予了立陶宛建筑以创作的激情、适应的韧性和改变的勇气。简要地回溯其一个多世纪现代性的转变不难看到,它曾经被追求,继而被遗忘,然后又被重新发现。在建筑语言方面,我们必须接受立陶宛丰富的多面向的背景。在这里,最好的定义方式是通过它不是什么,而非它是什么——就像阿多诺的负向辩证法那样。

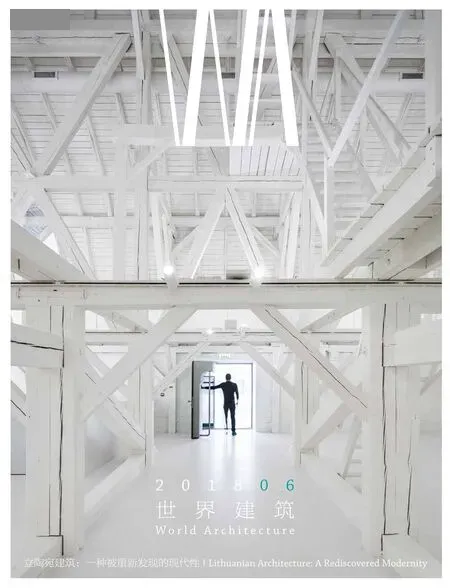

考纳斯在20世纪初的成功,是立陶宛现代性的一个惊艳绽放。它为当下不少21世纪新兴都市的大兴土木树立了先例——与今天相比,尽管资金有限,但知性更足。它独一无二的特性在于与前工业工艺的密不可分的联系:密斯式的技术至上与冷静在此骤然变成了工业与前工业之间的一种舒缓的和解。在苏联时期,我们看到了在新古典主义表皮辉煌之下的对物质和工艺情感的延续。1990年代后,当立陶宛建筑语境回归到自下而上的阵型时,对木、石头和混凝土的痴迷出现在更多激动人心的实验性探索里。在纹理、颜色和形状的交织中寻找瞬时与永恒的建筑,自那时起成为了一个不断被眷顾的话题。诗人马利乌斯·布洛卡斯在他的作品《将我变为骰子》中形象地向我们展现了立陶宛人感知事物、体察有形空间并赋予其意义的方式:

……

我温顺地低下我的头

一切——都不属于我——

自行车、早晨的面包店在愉悦中搁浅的身体,凝结的沥青,

杂货铺

踩旧的地板,

鹿角虫

……

然后我们可以面面相对在铺垫着纺布的桌上,在这里

我们占有全部的时间在每个人都淹没以前在绽放的绿色里

这或许正是我们在这次立陶宛建筑专辑中所试图寻找的立陶宛方式。我们相信,立陶宛对身份认同的探寻可以为中国的类似问题带来启发。我们也相信,与立陶宛独立百年同时出版的立陶宛建筑专辑将是今后一系列文化合作项目的第一步。

我们特别感谢立陶宛共和国驻中华人民共和国大使馆、立陶宛建筑师学会、立陶宛文化学院、阿格涅·波琉奈特女士、鲁塔·莱塔奈特女士。□

In a highly globalised 21st century world, more and more countries are getting reluctant to take the issue of identity seriously.Lithuania is one of the few exceptions. Today, it is not news that identity is a haunting subject, a politically dangerous one in particular.So why tackle the weight of contentious history processes while there is the reassuring easiness of circulating cheerful, universal stuff across the internet? The Lithuanian answer to this is an unmistakable one:because it is a must; because it is what we are.

A small nation sitting in the marginal overlays of regional powers is never blessed with geo-political security. However, such a nation is usually blessed with rich and exciting cultural cross fertilisation. Lithuania is such a case. In more than a century of the recent past, Lithuania has been trying to solve the identity conundrum upon the intertwining substrate consisting of European traditions, the Soviet years and the reestablishment of an independent Baltic nation. Nevertheless it is exactly this anxious quest that has given Lithuanian architecture a passion to make, a latitude to adapt and a courage to transform. A brief looking back would end up with a century of shifting modernity: once pursued, then forgotten, then re-discovered. In terms of architectural language, we have to embrace the richness of a multi-faceted milieu, best defined by what it is not rather than by what it is, in the typical Adorno's fashion.

The success of Kaunas in the early 20th century was a phenomenal opening of Lithuanian modernity. It well precedented the emerging capital cities of the 21st century, albeit with less money and more intellect. What made it unique was its inseverable connection with pre-industrial craft. The coolness of Miesian technocracy suddenly turned into a soothing reconciliation between what was industrial and what was not. We witness the same affection with material and craft continuing in the Soviet years, quietly residing beneath the neoclassical surface grandeurs. When Lithuanian architecture turned back to the more bottom-up discourse after the 1990s, the obsessions with wood, stones and concrete returned in even more exciting experiments.The architecture that seeks both time and timelessness among the orchestrations of textures, colours and shapes has since been prevailing.What the poet Marius Burokas wrote in his Turn me in to a Dice gives us a hint of the Lithuanian way of perceiving a tangible space of things and associating it with a meaning:

......

I meekly submit my head

and everything – that's not mine –

the bike, the bakery in the morning

with bodies smothered in pleasure,curdled asphalt,

the general store

with foot-worn floor,

stag-beetle

......

then we can face each other

over the cloth-covered table,

here while time is ours

before everyone drowns

in the roaring green

It is this Lithuanian way that we are seeking in our publication of Lithuanian architecture. We believe the Lithuanian quest in identity can lend some ideas and inspirations to our own in China.We also believe that this WA special issue on Lithuanian architecture,coinciding with the Lithuanian Centenary, would be the first step of a series of culture collaboration projects in the coming future.

Our special thanks to the Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania in People's Republic of China, Architects Association of Lithuania, Lithuanian Culture Institute, Ms. Agnė Biliūnaitė and Ms. Rūta Leitanaitė. □