The Use of Stance Bundles in English Academic Writing by L1 Mandarin Learners: A Corpus—Based Study

2018-01-23刘文博

【Abstract】Stance bundles signal the mastery of a certain academic discourse and accordingly this study combined corpus data and interview data to compare the usages of stance bundles across different language proficiency. Through a corpus analysis, it was found that UG learners tend to give personal and overstated arguments, while TESOL learners demonstrate a better control of the examined stance bundles and use more phrasal varieties and fixed bundles. There was an incremental mastery of using stance bundles from the UG to TESOL level. It was suggested from the subsequent interview that factors such as instruction and L1 transfer might influence the use of stance bundles.

【Key words】Lexical bundles; Epistemic stance; Corpus analysis; English academic writing

【作者簡介】刘文博(1991.08-),女,汉族,天津人,南开大学经济与社会发展研究院,行政,硕士研究生,研究方向:语料库语言学与英语教学 。

1. Introduction

As a building block of English academic writing, lexical bundles signal the mastery of academic discourse and make writers as insiders of that community. Among the three functions that lexical bundles convey, epistemic stance function is a crucial area in academic writing, in which writers are required to balance facts and possibilities. It seems that, however, the use of stance bundles in L2 writing differs from L1 English writing and there appears to be inconsistent among learner groups with different proficiency levels. Therefore, the focus of this study is bundles with stance functions in L2 English writing.

Considering the fundamental role of both lexical bundles (e.g. OKeeffe et al. 2007) and epistemic stance (e.g. Adel 2014) in academic writing, as well as the paucity of studies on L1 Mandarin-learner writing, this study investigated stance bundles in academic writing and endeavoured to make a contribution to raising L2 learners awareness of producing native-like stance bundles. Through corpus analysis, this study compared different usages of stance bundles between L1 English writers and L1 Mandarin-learners of L2 English at different proficiency levels (intermediate and advanced) and finally to explore some possible reasons for the differences.

2. Literature Review

In academic discourse, formulaic language has been seen as a cornerstone and tends to reduce language processing effort and thus increases language fluency and enables language production (Wary 2002). Unlike the consensus on the importance, however, terminology of formulaic language tends to be varied, such as lexical bundles (Biber et al. 1999), clusters (Hyland 2008) and formulaic sequences (Wray 2002). The present study prefers to narrow down formulaic language as lexical bundles, referring to the recurring sequences that contain more than three words (Biber et al. 1999, p. 990). Three discourse functions of lexical bundles (stance expressions, discourse organizer and referential expressions) have been proposed by Biber and Barbieri (2007) with specific sub-types under each category, among which there is a growing focus on stance function in studies of academic writing, because L2 English learners seem to have difficulties in detaching writing persona and being objective (Adel 2014), consequently resulting in informal writing styles.

It is evident in several studies that stance bundles are underused in L2 writing, and some stance expressions in L2 writing appear to be either brusque or dogmatic (e.g. Hyland & Milton 1997; Schleppegrell 2004; Hyland 2008; Aull & Lancaster 2014;). In Hyland and Miltons study (1997), it was revealed that L2 learners used fewer epistemic clusters than native speakers, and non-harmonic clusters can be found, which indicates that L2 learners “fail to achieve a congruent degree of certainty”. Taking stance bundles as the main focus, Schleppegrell (2004) concluded that L1 English writers opt for objective stance bundles, such as it is likely that, while L2 writers prefer subjective stances, such as I think. Focusing on IL/IL comparison in terms of language proficiency, Hyland (2008) explored the forms, structures and functions of four-word bundles in masters theses, doctoral dissertations and research articles based on corpus analysis. The functions of the bundles in the study fell into three groups: research-oriented (e.g. at the beginning), text-oriented (e.g. on the other hand) and participant-oriented (e.g. are likely to be; it should be noted), among which participant-oriented clusters or stance bundles were discussed in detail. Masters students writing-discourse was featured with infrequent use of stance bundles relative to the other two groups. Stance bundles in doctoral dissertations appeared to be more varied and numerous, which, on the other hand, served to engage readers rather than, “convey[ing] epistemic and affective judgment, evaluations and degrees of commitment” (2008, p. 55). Research articles not only contained more participant-oriented clusters than the other two groups, but also two-thirds of the clusters were stance bundles that functioned as withholding complete commitment from propositions and showing writers tentativeness. With respect to sub-categories of stance bundles, Aull and Lancaster (2014) discovered that learners with lower English-levels underused “hedges, code glosses, concessions and contrast expressions”, but overused “boosters and adversative connectors”. Related studies have encouraged L2 learners to adopt an objective and critical stance and “a highly attitudinal, forceful and assertive stance is less valued” in academic writing (p.155).

All four studies, therefore, displayed the importance of stance bundles in academic discourse and the difficulties of stance bundles for L2 learners. It can be argued, however, that there may lack research on L2 learners with different L1s, especially L1 Mandarin-learners.

Accordingly, there are three research questions guiding this study:

a. What differences are there in using stance bundles in academic writing between L1 Mandarin-learners of L2 English and L1 English-writers? (Corpus data)

b. What differences are there in using stance bundles across English-proficiency levels of L1 Mandarin-learners of L2 English? (Corpus data)

c. What are L2 learners perspectives on reasons for the ways they use stance bundles? (Interview data)

3. Research Design

This part will give the rationale for the research design and execution of the research.

3.1 Rationale and Procedures

The study adopted a sequential explanatory design, in which quantitative data collection and analysis was followed by qualitative data analysis. This study designed three target corpora: BAWE, TESOL and UG, among which TESOL and UG writings were collected from participants and L1 writing was selected from the BAWE. After building the corpora, the most frequent stance bundles were categorised into it-bundles, modal VPs, and lexical VPs based on literature (Biber et al. 1999, p.1014-1024) before counting the frequencies in BAWE. Afterwards, the corresponding frequencies of these stance bundles were counted in TESOL and UG learner writing respectively. Thus, there was a contrastive wordlist regarding normalised frequencies of these stance bundles in the three corpora, followed by contrastive analysis between BAWE and TESOL, and TESOL and UG respectively. After comparing frequency data, concordances were employed to display typical usages in each corpus and differences among the three in order to supplement frequency data. Therefore, difference usages of stance bundle were highlighted and the first two research questions can be answered. At the second stage, semi-structured interviews were conducted in order to answer research question c.

3.2 Participants

Overall there were 60 participants in this study and all of them are L1 Mandarin-speakers under 25 years old. 20 students (17 females and 3 males) on MSc TESOL program at a University in the UK contributed two argumentative essays each to build an advanced learner corpus (TESOL corpus). The overall criteria were: they reached at least band 6.5 in IELTS writing test; had less than 6 months teaching experience of English; studied in the UK for more than 6 months. The second learner corpus was built from 40 undergraduate theses from 40 students (38 females and 2 males) in a university in China. The selection criteria were: they were English majors and passed TEM 4 (Test for English Majors Band 4); had no experience in studying abroad and no working experience.

For the interview participants, 5 in each group were chosen. It needs to be mentioned that participants informed consents were signed and confidentiality and identifications were well preserved.

3.3 Corpus Data Collection and Analysis

Altogether there were 40 assignments in the TESOL corpus, constituting 6,704 word types and 130,381 word tokens in total without proofreading. UG corpus consists of 40 undergraduate theses that were collected from 40 English majors, containing 11,979 word types and 235,800 word tokens. The reference L1 English corpus is from BAWE with 11,305 word types and 123,362 word tokens. Therefore, learners level, disciplines, genres and corpus size make the three corpora comparable and thus enhance reliability of data results. However, there was a gender imbalance in the learner corpora with great numbers of female learners. Seeing that it was also a case in BAWE, the comparability of the three corpora was increased to make up for the limitation.

The first step of corpus analysis was to identify frequently used bundles with a stance function in BAWE. Table 3-3-2 captures the categories of stance bundles that were used in this study, which also served as a reference list to identify bundles in BAWE. BAWE was put in AntConc 3.4.3 and through searching bundles in the N-Grams Tool (scans “N” word clusters in the entire corpus) or concordance, frequencies of each bundle were calculated and non-epistemic usages were manually noted. The final step of analyzing BAWE data was to select the most frequently used bundles in each category.

Similarly, using the bundles in BAWE as a reference, L2 learner writings were analysed in AntConc. After creating the Word List, each stance bundle was searched in Clusters/N-grams or Concordance in order to work out frequencies of the corresponding stance bundles and the number of non-epistemic usages were noted as well. Subsequently, it would form contrastive lists of stance bundles in the three corpora, which afterwards were manually inputted into Microsoft Excel 2003 software in order to generate graphs. Through contrastive analysis, typically overused/underused and pragmatically misused stance bundles in L2 writing were discussed that would answer the first two research questions.

3.4 Interview Data Collection and Analysis

In the next step, semi-structured interviews were conducted based on the corpus results in order to answer research question c. Interviewers will follow guided questions and be freer to probe beyond prejudicial answers or discuss unexpected explanations in detail. The interview data analysis mainly followed “interaction-transcription-interpretation” process and thematic coding analysis was adopted when analyzing transcripts.

4. Corpus Data Result

This part will present data results of ADJs in It-Bundle, Lexical VPs, and Modal VPs.

4.1 ADJs in It-Bundle

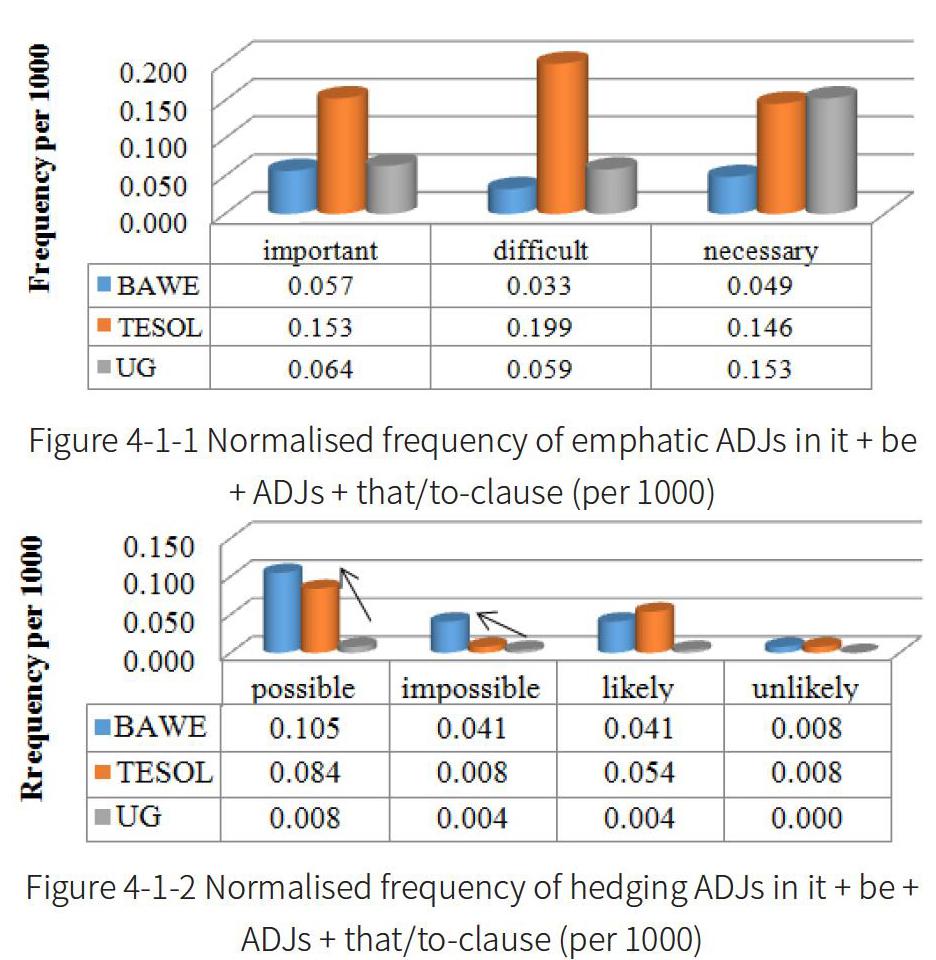

Figure 4-1-1 and 4-1-2 show seven adjectives that are frequently used in it + be + ADJ + that/to-clause, which can be classified into emphatics (draw conclusions or inferences) and hedges (withhold commitments or excuse responsibilities) based on the study of Hewings and Hewings (2002, p. 373) study. Overall, emphatic adjectives were overused in L2 learner writing relative to native writers and, in particular, overused approximately 3 times in TESOL writing. Frequencies of important and difficult in TESOL writing are higher than in UG writing.

In addition to emphatics, frequently used hedging adjectives in it-bundle (e.g. it is possible that) have been shown in Figure 4-1-2. It can be seen that the following hedging adjectives were underused in both L2 learner writings relative to L1 writing (except for likely in the TESOL corpus), particularly underused in UG writing. Frequencies also show the increasing usages of the following hedges from UG level writing to TESOL level writing.

4.2 Lexical VPs

Figure 4-2-1 presents the comparisons of using different lexical VPs among the three corpora. Two learner groups overused lexical VPs, where there was an overwhelming reliance on NP think in UG learner writing. However, NP argue (+ 0.509) and NP suggest (+ 0.7) were highly overused in TESOL learner writing. Regarding changes from UG to TESOL level, frequency of NP think decreases from 0.666 to 0.284 but frequencies of NP argue and NP suggest sharply increase from 0.038 to 0.590 and 0.110 to 0.943 respectively.

In L1 writing, NP think was used to give subjective evaluations or personal opinions while NP argue/suggest expressed writers evaluations in indirect ways, such as concordances (1) and (2) in BAWE. Similar usages were found in L2 writing, such as (3) in TESOL and (4) in UG writing and there were no obvious pragmatic differences between the two learner writings.

(1)This, I think can be seen as an accurate description of the situation in Gilead, where there is no female role that is wholly positive. (BAWE)

(2)Richards and Rodgers (2001) suggest that previous approaches: ‘draw on a large amount of collective experience and practice from which much can be learned. (BAWE)

(3)Some people argue that the practice of altering to the L1 in the classroom has no pedagogical values....(TESOL)

(4)Because parents think that children are too young to distinguish what is right or wrong. (UG)

4.3 Modal VPs

The examined modal VPs are presented in Figure 4-3-1 and 4-3-2, in which will/would be indicate certainties, must/should be can express probabilities while may/might/could be convey possibilities (Quirk et al. 1985, p. 222-223). Overall, most examined modal VPs were overused in TESOL and underused in UG compared to L1 writing. In Figure 4-3-1, frequencies of must be are similar in the three groups, but will be and would be were underused in UG writing. It is obvious to find should be was highly overused in the two learner writings, especially in TESOL writing. In Figure 4-3-2, may be and might be were not frequently used in UG writing. In the two figures, frequencies of modal VPs in TESOL writing are closer to L1 English writing.

In addition to the frequencies, concordance data also shows different pragmatic usages among the three corpora. Instance (5) shows that L1 writers used must be based on the evidence or experience, while L2 learners employed must be to propose obligations or responsibilities, such as (6) and (7).

(5)Thus, there must be other factors that influence our decisions to begin and end consumption.(BAWE)

(6)In other words, strategies must be explicated to students to solve their problems (TESOL)

(7)So this questionnaire must be well-designed before being conducted. (UG)

Epistemic function of will be was frequently used in L1 writing (8) and sometimes in TESOL writing (9), but its future predictive sense was preferred by UG learners, either in an adverbial clause of condition (10) or to explain structures of essays (11).

(8)It will be necessary to show that the deficiencies of both of these traditional ontologies stem from their grounding in empiricism, … (BAWE)

(9)Therefore it will be difficult for them to collaborate with teachers in learning process. (TESOL)

(10)Also, some communication strategies will be useful if applied properly in conversation. (UG)

(11)This thesis will be presented in five chapters. (UG)

Concordance data in BAWE indicates should be was used based on expectations and further verifications, such as (12). Although similar instances can be found in L2 writing, using should be to stress obligations and suggest improvements take up a large proportion in L2 writing, as in (13). In addition, should be and would be are related to hypothetical expressions of tentativeness or politeness (Quirk et al. 1985, p. 233-234). Would be in BAWE was typically used in its hypothetical meaning and interpreted as unreal conditions (14). However, TESOL learners commonly employed the bundle it would be better/helpful to express willingness while UG learners preferred its future predictive sense (15).

(12)…some reference to dearth would exist in one form of source and there should be fewer conceptions than usual. (BAWE)

(13)… so L1 use is negative and should be prohibited. (TESOL)

(14)A number said that if pronunciation were more obviously integrated into the syllabus and course-books they would be more willing and able to teach it. (BAWE)

(15)Then these data would be type-in and processed by SPSS19.0. (UG)

5. Corpus Data Discussions

This part will give detailed discussions of corpus data.

5.1 ADJs in it-bundle

The overuse of emphatic adjectives leads to overstatements in learner writing, and the underuse of hedging shows L2 learners may stamp their personal authorities onto arguments and have difficulties in weakening claims. The reliance on important, necessary and difficult shows L2 learners made apparently greater overt efforts to convince readers of the validity of their claims. Hewings and Hewings have explained that, “the more significant the contribution, the more their work will be valued, and that the more forcefully their contribution is presented” (2002, p. 381). In other words, the strategic purpose of the following bundles is to emphasise validity of their statements and their contributions, but none of these arguments can be easily accepted. Focusing on the two learner groups, UG learners tend to give stronger propositions than TESOL learners by simultaneously using adverbs (16). Although TESOL writing showed higher frequencies of emphatic adjective use and stronger statements than that of L1 writers, they had better control of giving an appropriate stance relative to UG learners, which indicates progress from intermediate to advanced level.

(16) It is extremely important for audience to appreciate the film. (UG)

The use of emphatics suggests L2 learners put forward more forceful statement than is appropriate and the stronger claim calls for hedging expressions. In L1 writing, hedging functions as, “speculat[ing] about possible generalisations for which there is little or no empirical evidence” on propositions (Adel 2014, p. 77). Comparing the three target groups, L1 writers used more hedges than L2 learners in terms of numbers and varieties, and TESOL learners had better control of hedging adjectives than UG learners. Focusing more on UG learners, lower frequencies of using hedging adjectives reveal the difficulties or unawareness of exempting themselves from taking full responsibility and showing possibilities. Similarly, several studies (e.g. Aull & Lancaster 2014) have proposed that in English academic writing, L2 learners appear to struggle with giving propositions, expressing doubts and withholding commitments.

5.2 Lexical VPs

The overuse of NP think shows that L2 learners prefer to modify their arguments with personal expressions and writing persona, which indicates inappropriate academic tenor. This is because bundles such as I think or I believe are explicit subjective modalities, expressing writers viewpoints and politeness strategies in interactive discourse, or mitigation of assertions or disagreements. Thus, the highly used I think in learner writing shows learners tendency to use a personal pronoun with a lexical verb to convey, “an assessment of propositional validity” (Hyland & Milton 1997, p. 198). Frequently used NP argue/suggest may indicate TESOL learners attempts to avoid strong assertions and employ various bundles in their writing. It should be argued, therefore, that learners with lower-levels are more likely to adopt such stance bundles and the trend of frequencies declines as proficiency increases.

5.3 Modal VPs

The overuse of modal VPs and preferences for the root meaning indicate that L2 learners have rudimentary understandings of the examined modal VPs and tend to be direct and authoritative by making strong modals. The generalised overuse of the examined modal VPs in advanced writing (TESOL) is consistent with Aijmers (2002) findings, in which she found the examined models were overused in advanced L1 Swedish learner writing. In this study, however, learners with lower English-proficiency levels underused the modal VPs (except for must be and should be), especially the epistemic interpretations. Modal VPs are complicated for novice learners largely owing to the, “poly-pragmatic” feature that modal VPs can simultaneously express different meanings (Hyland & Milton, p. 185). One possible evidence of the limited usage lies in the differences in using will be/would be, a favoured stance marker of certainty in L1 writing (p. 188). The great reliance on using will/would be to express future tense shows the uni-functional or non-epistemic manner in L2 writing.

5.4 Summary

Differences in using stance bundles have been discussed in order to answer the first research question. L2 learners tend to give overstatements and are not able to use hedges. In addition, personal evaluations have been discovered from discussion of NP think, which indicates the confusion of using an appropriate tone in academic writing. Regarding modal VPs, L2 learners restricted their usages to root meaning rather than epistemic functions.

Focusing on the two learner groups with different language-proficiency levels, some differences could be concluded to answer research question b. UG learners expressed stronger convictions, subjective evaluations and speech-like expressions in their writing. In contrast, TESOL learners showed better control of stance bundles and the awareness of how to weaken claims. Thus, in accordance with Aull and Lancasters (2014) findings, this study found that TESOL writing was closer to L1 writing and there is a progress of using stance bundles from intermediate level to advanced level.

6. Interview Data Results and Discussions

Interview data presents that 5 UG learners are unfamiliar with epistemic stance bundles in academic English writing and 3 of them have only learnt to avoid using I think in their writings. In contrast, all the TESOL participants had awareness of epistemic stance and they gave some instances of bundles as well, such it is possible. All interviewees mentioned that instruction in EFL education in China was limited and TESOL learners, particularly, contributed their awareness to academic-writing courses in English Language Teaching Center (ELTC) in PG studies. More specifically, 10 participants attributed their usages of stance bundles to limited instruction and L1 transfer.

L2 learners acquired epistemic stance mainly through instruction from textbooks and from classroom teaching. All the participants argued that information in textbooks/classroom of epistemic stance was limited and need to be enriched. In Chinese EFL context, the study points strongly to the necessity of providing wider varieties and alternative strategies of expressing stance in textbooks, and placing modal VPs in various discourse perspectives, enabling both semantic and pragmatic understanding.

In addition to instruction, L1 transfer has been discussed regarding the high use of I think in L2 writing. Interview data lends support to the theoretical hypothesis that, “worenwei/wojuede” in Chinese may cause the frequent use of I think, and TESOL interviewees exemplified I think as a typical L1 negative transfer. It is interesting to find that when conducting the interview, all the interviewees were habitually starting with wojuede or I think to give their viewpoints. Thus, empirical interview data back up the hypothesis that L1 Mandarin transfer influences the ways of giving stance.

7. Conclusions

The study found that L2 learners tend to give personal evaluations and overstatements, indicating that they may not be able to use hedges to withdraw commitments and project an appropriate stance. Further, the over-reliance on the non-epistemic meaning indicated limited mastery of modal VPs in L2 learner writing (RQ a). In terms of the two learner groups, the UG learners were found to express stronger convictions and have register confusions. On the contrary, the TESOL learners had a better control of the examined stance and employed more phrasal varieties (RQ b). There was an incremental mastery in using stance bundles from UG to TESOL level and edging closer to L1 English usages. It was suggested from the interview that limited instruction and L1 transfer contributed to the lack of using epistemic stance bundles (RQ c).

Research up to the present has only scratched the surface of epistemic stance in L2 development. For future research, it would be more beneficial to conduct a diachronic research that focuses on the same group and tracks their progress in using stance bundles.

References:

[1]Adel,A..Selecting quantitative data for qualitative analysis: A case study connection a lexicogrammatical pattern to rhetorical moves[J].Journal of English for Academic Purposes,2014,vol.16:68-80.

[2]Aijmer,K..Modality in advanced Swedish learnerswritten interlanguage.In S Granger,J Hung & S Petch-Tyson(eds.),Computer learner corpora:Second language acquisition and foreign language teaching[J].John Benjamins Publishing Company,Amsterdam and Philadelphia,2002.

[3]Anthony,L..AntConc(Version3.4.3)[D].Waseda University,Tokyo, Japan,2014.

[4]Biber,D&Barbieri;, F..‘Lexical bundles in university spoken and written registersEnglish for Specific Purposes[J].2014,vol.26:263- 286.

[5]Biber,D,Johansson,S,Leech,G,Conrad,S&Finegan;,E1999, Longman grammar of spoken and written English, Longman, Harlow.

[6]Hewings,M&Hewings;,A..“It is interesting to note that…”:A comparative study of anticipate“it”in student and published writing[J].English for Specific Purposes,2002,vol.21:367-383.

[7]Hyland,K..‘As can be seen:Lexical bundles and disciplinary variation[J].English for Specific Purposes,2008,vol,27,no.1:4-21.

[8]Hyland,K & Milton,J..Qualification and certainty in L1 and L2 students writing[J].Journal of Second Language Writing,1997, vol.6,no.2:183-205.

[9]OKeeffe,A,McCarthy&Carter;,R..From corpus to classroom: Language use and language teaching[M].Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[10]Quirk,R,Greenbaum,S..Leech G&Svartvik;,J..A comprehensive grammar of the English language[J].Longman,London and New York, 1985.

[11]Schleppegrell,MJ..Technical writing in a second language: The role of grammatical Metaphor,In LJ Ravelli & RA Ellis (eds),Analyzing academic writing:Contextualised frameworks[J].Continuum, London,2004.

[12]Wray,A.Formulaic language and the lexicon[M].Cambridge University Press,Cambridge,2002.