The “Colonial Wig” pancreaticojejunostomy:zero leaks with a novel technique for reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy

2017-10-09XihuaYangPouyaAghajafariNaeemGoussousShiraliPatelandStevenCunningham

Xihua Yang, Pouya Aghajafari, Naeem Goussous, Shirali T Patel and Steven C Cunningham

Baltimore, USA

The “Colonial Wig” pancreaticojejunostomy:zero leaks with a novel technique for reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy

Xihua Yang, Pouya Aghajafari, Naeem Goussous, Shirali T Patel and Steven C Cunningham

Baltimore, USA

BACKGROUND: Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) remains common and morbid aer pancreaticoduodenectomy(PD). A major advance in the study of POPF is the fistula risk score (FRS).

METHODS: We analyzed 48 consecutive patients undergoing PD.e “Colonial Wig” pancreaticojejunostomy (CWPJ)technique was used in the last 22 PDs, we compared 22 CWPJ to 26 conventional PDs.

RESULTS: Postoperative morbidity was 49% (27% Clavien grade >2).e median length of hospital stay was 11 days. In the first 26 PDs, the PJ was performed according to standard techniques and the clinically relevant POPF (CR-POPF) rate was 15%, similar to the FRS-predicted rate (14%). In the next 22 PJs, the CWPJ was employed. Although the FRS-predicted rates were similar in these two groups (14% vs 13%), the CRPOPF rate in the CWPJ group was 0 (P=0.052).

CONCLUSION: Early experience with the CWPJ is encouraging, and this anastomosis may be a safe and effective way to lower POPF rates.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2017;16:545-551)

pancreatectomy;

postoperative pancreatic fistula;

fistula risk score;

anastomosis;

novel surgical technique

Introduction

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is one of the most common and troublesome complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD),[1]an increasingly common operation for a variety of benign and malignant periampullary diseases, including cystic and solid lesions, pancreatitis, and, rarely, trauma.[2-6]Furthermore, the increasing age of the population undergoing PD, and the increased awareness of risks associated with cancer surgery in the elderly,[7]have given rise to an enlarging and sometimes controversial literature suggesting that rates of POPF may be even higher among older patients.[8-10]Sopancreas texture is strongly associated with risk of POPF.[1,8,10,11]Indeed, an increasingly employed, and recently validated, fistula risk score (FRS)predicting POPF has consistently found that sogland texture, small duct diameter, are among the most powerful predictors of POPF.[12,13]Although the grading of POPF has become increasingly standardized over recent years, the techniques for pancreatic anastomosis are diverse and there is no standardized operation procedure.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the last 50 consecutive patients who were operated upon by the senior author(CSC) for pancreatic head resections at a high-volume pancreatic surgery program at a community teaching hospital from August 2010 to February 2016. Patients undergoing total pancreatectomy and those having com-plications precluding assessment of POPF (e.g., early postoperative mortality) were excluded. Approval of the local Institutional Review Board was obtained.

Patient data included variables used to calculate the FRS[12,13](gland texture, pathology, diameter of the pancreatic duct and intraoperative blood loss), the Clavien complication grade[1](need for any treatment deviating from the modified pancreatectomy pathway[14-16]), and the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery(ISGPS) grade of POPF[17,18](drain amylase level, length of hospital stay, readmission and reoperation). Computed tomography (CT) scans were performed for suspicion of intraabdominal fluid collections. Drains with outputs low in amylase or volume were removed at the discretion of the surgeon.

Conventional PD

In the first cohort of 26 consecutive PDs from August 2010 to January 2014, the pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) was performed in either the duct-to-mucosa (n=24) or an endto-end invaginating technique (n=2) according to standard techniques.[19]In particular, the technique for these first 26 cases was as follows: for duct-to-mucosa anastomoses, an outer interrupted layer of 3-0 silk was placed through the posterior surface of the pancreas, and then through the jejunum in a seromuscular fashion. Next a jejunotomy was created the same size as, and exactly adjacent to, the pancreatic duct.e duct-to-mucosa anastomosis was performed with interrupted 5-0 or 4-0 synthetic absorbable monofilament suture, first the posterior sutures and then the anterior ones.e outer anterior layer was then secured with a row of closely spaced interrupted 3-0 silk sutures in a Lembert fashion. In the other 2 cases (end-to-end invaginating technique), the end of the pancreas was placed into the end of the jejunum for a distance of 5 cm and then the jejunum was secured circumferentially to the body of the gland.is was accomplished by generously mobilizing the end of the pancreas and then by placing stay sutures 2.5 cm from the cut end of the pancreas on the superior and inferior borders.ese sutures were then tied, then passed into the end of the jejunum with French eye needles, and then passed out the sides of the jejunum 2.5 cm from its end. When tied, these sutures secured the pancreas, inserted 5 cm into the jejunal lumen.e cut end of the jejunum was then secured hermetically to the body of the pancreas in a circumferential fashion with closely spaced 3-0 silk interrupted sutures.

“Colonial Wig” PJ

In the second cohort (n=22) from March 2014 to February 2016, a novel PJ, the “Colonial-Wig” PJ (CWPJ)was performed as described below.

General principles

PD was performed as previously described.[20]Reasoning firstly that leaks occur not only from the main pancreatic duct, but also from small ductules on the cut surface of the pancreas,[21]we used a compressive U-stitch to securely invaginate the pancreas; reasoning secondly that anastomotic corners are especially susceptible areas for leaking, we developed a technique to both dunk the corners of the pancreas (with stay sutures, using French eye needles), and also to bury the corners deep within a wrapped jejunal buttress (which grossly resembles a namesake “Colonial Wig” [CW]); reasoning thirdly, that an additional tension-free, hermetic layer would be optimal, we took advantage of the redundant cuffof jejunum,resultant following the U sutures (see below), to hermetically suture this cuffto the pancreatic capsule without tension, and then further buttressed with an omental flap.We term this anastomosis the CWPJ.

Detailed technique: sutures and rationale

Prior to division of the pancreatic neck, four 3-0 silk stay sutures are placed in a standard fashion, two at the superior border and two inferiorly, to ligate the longitudinal pancreatic arteries and later to retract the pancreas. Aer the neck of the pancreas is divided, typically with a scalpel, and the specimen removed, the stapled end of the jejunum is positioned for anastomosis as previously described.[20]

As shown in the Fig., the four sets of sutures, and their rationale, in order of placement, are the following: 1)e two 3-0 silk stay sutures (s) placed prior to division of the pancreatic neck, which during the anastomosis will serve to secure the invagination of the corners of the pancreatic remnant into the jejunum; 2) Two 3-0 silk CW sutures (cw)that wrap the jejunum around the invaginated pancreas,covering the anastomotic corners completely with jejunum and giving the final product the appearance of a colonial wig that the pancreas wears (Fig.); 3) Two 3-0 glycolide/lactide copolymer (or polyglactin) U-sutures (u) that compress the small ducts and securely invaginate the pancreas, similar to the “dunking PJ”;[22]and 4) Several very closely spaced 3-0 silk interrupted sutures that provide an outer-layer (o) of additional hermetic sealing between the redundant cuffof jejunum remaining aer tying the U sutures, and the pancreatic capsule (Fig.).

Before tying the U sutures (u), French eye needles are used to pass the free ends of the stay sutures (s) in-to-out through the full thickness of jejunum approximately 1 cm from the jejunotomy (Fig. A, B), which is made to allow the entire pancreas remnant to fit snugly within the jejunum. As the two stay sutures (s) and the two U sutures (u) are pulled taut, the pancreas enters the jejunotomy and is secured in a deeply invaginating position within the jejunum (Fig. B).

Next, several very closely spaced interrupted 3-0 silk outer sutures (o) are placed to provide an additional layer of hermetic sealing, tension-free. Anteriorly, these join the redundant cuffof jejunum between the tied U-stitches, and the cut edge of the jejunum in a tension-free manner (Fig. D). Posteriorly, these may be placed prior to the above, or, if the PJ is mobile enough then they may be placed last. Care is taken not to tear the pancreatic capsule. Finally, the anastomosis is wrapped or at least covered by a harvested tongue of omentum. Two 19-F round, fluted (e.g., Blake) silicone drains may be placed near, but not touching, the PJ, which is protected from the drains by the omental flap.

Specimen marking and pathologic dissection techniques

All relevant margins, viz., the superior mesenteric artery (uncinate) margin, the posterior margin, the superior mesenteric vein/portal vein (vein-groove margin),the pancreatic neck (transection) margin, and the bile duct margin, were marked and/or discussed directly with the pathologist to ensure accurate reporting. Pathologic dissection of the specimen followed the Johns Hopkins technique.[24]

Statistical analysis

A Chi-square test was used to compare categorical data and a Student'sttest for sample mean. Significance was accepted at aPvalue of <0.05.

Results

Of 50 consecutive pancreatic head resections, 48 were PDs (two total pancreatectomies were excluded because of the lack of a PJ). Nearly all patients (96%) had comorbidities with a median of 5 per patient in each group.e median blood loss was 500 mL and 35% of cases required an intraoperative blood transfusion (mean of 0.7 units/operation).e two groups did not differ regarding blood transfusions: 9/26 patients in the first group received transfusions, and 7/20 in the CW group(P=0.98). Similarly, there was no significant difference in operative time between the groups.e final pathology was periampullary carcinoma in 41 (85%) of the 48 cases.e average number of lymph nodes harvested was 20.e margin-negative rate was 90% among neoplasia cases (two cases not included in this calculation were for benign disease: one case of a lipomatous mass, and one pseudoaneursym). All margin-positive neoplastic cases were R1 (microscopically positive), except one palliative R2 (grossly positive) case done because of bleeding.e median length of hospital stay was 11 days and the readmission rate was 9/48 (19%).

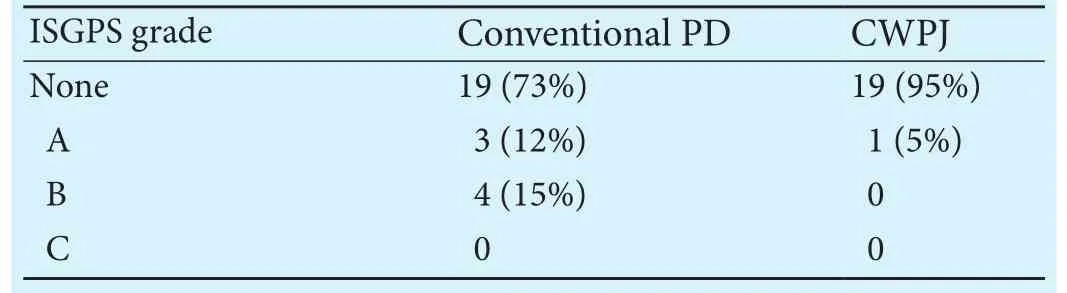

Table 1 shows the POPF rate for the first 26 PDs.e overall rate was 27%, including 3 (12%) grade A (clinically insignificant) fistulas, 4 (15%) grade B, and 0 grade C fistulas.is clinical relevant POPF (CR-POPF) rate of 15% was similar to that predicted by the FRS for this cohort (14%). However, in the next 22 PJs, the “Colonial Wig” anastomosis was employed, with a CR-POPF rate 0(P=0.052) among eligible cases (two were excluded due to inability to evaluate the POPF rate, as described below).ere was one grade-A POPF in the CW group (5%).

Table 1.Comparison of conventional PD and CWPJ cases by occurrence and grade of POPF

Morbidity and mortality

Discussion

It is a surgical truism that the more ways that exist to accomplish a given goal, such as creating a PJ aer a PD, the less likely that there is a single salient way that is obviously better than all the others, since otherwise the best way would be universally applied.is is certainly true in pancreatic surgery, which is a field in evolution,especially regarding the pancreatic anastomosis.ere are currently nearly 1000 PubMed results with the term“pancreatiojejunostomy” in the abstract, and nearly 500 with the term in the title, not to mention hundreds with the term “pancreaticogastrostomy.” Regarding the PJ itself, the literature is replete with small series with new techniques reporting zero or near-zero leak rates. Why then add another with the current study?e answer to this question is simply that despite all the existing literature, POPF is still widely recognized to be the Achilles'heel of the PD, and more work needs to be done.

Taking into account the likely technical sources of a POPF, such as the small duct branches on the cut surfaceof the pancreas, the corners of the anastomosis, and the anterior and posterior suture lines, we have designed a novel PJ that combines all of the best features of other anastomosis, and have further guarded against POPF with three adjunctive measures.

One of these adjuncts, the omental flap, was used routinely as a final step of the anastomosis, and the other two, octreotide and decompression of the pancreaticobiliary limb, was use selectively for high-risk cases. Data on the use of an omental flap to prevent POPF are mixed,with some studies, including a meta-analysis, showing no benefit[26]and some showing a reduction in the rate of POPF.[27,28]Unfortunately, these studies are not randomized controlled trials and the overall quality of the data is not convincing. Decompression of the pancreaticobiliary limb may be done with a Braun enteroenterostomy (as was done in this series) or by tube decompression.e use of a Braun enteroenterostomy, which should theoretically decrease rates of POPF as well as delayed gastric emptying, has been studied in numerous nonrandomized studies,[29-31]and is currently the topic of a randomized controlled trial ongoing at Johns Hopkins (NCT01481753 at ClinicalTrials.gov). While a Braun is likely useful for preventing delayed gastric emptying, data supporting its use to prevent POPF are scant.[30]Similarly, the data on octreotide as a strategy to reduce POPF has been widely studied but still lacks broad consensus, and opinions vary widely.[32,33]Our rationale for using octreotide has been reported elsewhere.[33,34]Briefly, the rationale for octrotide use is both physiologic and statistical (evidence-based). Physiologically, although concern has been raised in retrospective studies[32]that octreotide suppresses anabolic and tropic hormones which participate in the healing process, this concern is not well supported by the literature.[33,34]In addition, octreotide use has excellent evidence-based support.[33-35]ere is currently little consensus among experts, however, regarding whether any or all three of these adjunctive maneuvers should be performed aer a PD, routinely or selectively or at all, and more data are needed.

In addition to these adjunctive maneuvers, the technical aspects of the anastomosis itself are specifically designed to target likely problem areas of the anastomosis: the small duct branches on the cut surface of the pancreas, the corners of the anastomosis, and the anterior and posterior suture lines.e small duct branches are a likely source of leaks in many duct-to-mucosa PJs. Although this is difficult to prove definitively, it is reasonable to assume that if these ducts are not compressed, ablated, or invaginated, but rather are leto leak into the potential space bound by the cut surface of the pancreas, the serosal surface of the bowel, the sutures of the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis, and the sutures of the outer serocapsular layer (e.g., Figures 30-31 in Cameron's Atlas of Gastrointestinal Surgery[19]), then risk of a POPF would be increased.e U sutures as shown in Fig. provide this compression, but more importantly, since the pancreas is invaginated, serve to secure this invagination deeply within the lumen of the jejunum. Two of the most common PJs, propagated by two of the greatest leaders in pancreatic surgery, Cameron's duct-to-mucosa invaginating PJ, here termed Cameron's DMIPJ (Figures 21-25[19])and Blumgart's PJ[36]both avoid the pitfall of leaking small duct branches on the cut surface of the pancreas by using compressing sutures. However, both of those techniques lack the broad “Colonial Wig” dunking of the corners, and like all anastomoses, both only partially compress the small ducts, thereby leaving some room for improvement. By contrast, our CWPJ protects the corners from leaking in two ways: first, the corners of the pancreas, which tend not to stay well invaginated, are securely invaginated by using the erstwhile stay sutures (“s”in Fig.) as corner-dunking sutures.is is easily done by simply using a French eye needle to pass the two loose ends of the stay suture in-to-out at the corners of the jejunostomy. Second, broadly wrapping the corners with a length of jejunum (thereby forming the wig appearance),as shown in Fig., provides an additional layer of coverage for the corners. Finally, the outer layer shown in Fig. D,as well as the omental wrap, provides an additional layer that is entirely tension-free, and ensures a hermetic quality.

Important future directions in this field are clearly the performance of more prospective randomized clin-ical trials.is anastomosis is easy to learn and would lend itself to application to a multicenter trial.

In conclusion, high-volume pancreatic surgery is possible at community, teaching hospitals, with morbidity comparable to that reported from university-affiliated centers.e existence of many PJ techniques suggests none is ideal for all surgeons.e best technique for now may be the one most familiar to the surgeon.e novel“Colonial Wig” anastomosis may be a safe and effective way to lower POPF rates aer PD, especially when the pancreas texture is soand POPF risk is high.

Acknowledgements:We thank Anne M Sill, MSHS, GME Research Coordinator and Department Statistician for careful review of the statistics.

Contributors:CSC proposed the study. YX, AP, GN and PST performed the research and wrote the first dra. YX, AP, GN, PST and CSC collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further dras.CSC is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:is study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Board) of Saint Agnes Hospital(2016-020).

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 DeOliveira ML, Winter JM, Schafer M, Cunningham SC,Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, et al. Assessment of complications aer pancreatic surgery: A novel grading system applied to 633 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2006;244:931-939.

2 Cunningham SC, Hruban RH, Schulick RD. Differentiating intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms from other pancreatic cystic lesions.World J Gastrointest Surg 2010;2:331-336.

3 Jani N, Bani Hani M, Schulick RD, Hruban RH, Cunningham SC. Diagnosis and management of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Diagner Endosc 2011;2011:478913.

4 Howard JM. Development and progress in resective surgery for pancreatic cancer.World J Surg 1999;23:901-906.

5 Gulla A, Tan WP, Pucci MJ, Dambrauskas Z, Rosato EL, Kaulback KR, et al. Emergent pancreaticoduodenectomy: a dual institution experience and review of the literature. J Surg Res 2014;186:1-6.

6 Griffin JF, Poruk KE, Wolfgang CL. Pancreatic cancer surgery:past, present, and future. Chin J Cancer Res 2015;27:332-348.

7 Kowdley GC, Merchant N, Richardson JP, Somerville J,Gorospe M, Cunningham SC. Cancer surgery in the elderly.ScientificWorldJournal 2012;2012:303852.

8 Haddad A, Cunningham SC, Demirjian A. Re: “Impact of age over 75 years on outcomes aer pancreaticoduodenectomy”. J Surg Res 2014;187:718-719.

9 Makary MA, Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Chang D,Cunningham SC, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in the very elderly. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:347-356.

10 Sulpice L, Rayar M, D'Halluin PN, Harnoy Y, Merdrignac A,Bretagne JF, et al. Impact of age over 75 years on outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Surg Res 2012;178:181-187.

11 Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Chang DC, Riall TS,Schulick RD, et al. Does pancreatic duct stenting decrease the rate of pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy?Results of a prospective randomized trial. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1280-1290.

12 Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, Chaikof EL, Vollmer CM Jr. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula aer pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:1-14.

13 Miller BC, Christein JD, Behrman SW, Drebin JA, Pratt WB,Callery MP, et al. A multi-institutional external validation of the fistula risk score for pancreatoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:172-180.

14 Kennedy EP, Grenda TR, Sauter PK, Rosato EL, Chojnacki KA,Rosato FE Jr, et al. Implementation of a critical pathway for distal pancreatectomy at an academic institution. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:938-944.

15 Kennedy EP, Rosato EL, Sauter PK, Rosenberg LM, Doria C,Marino IR, et al. Initiation of a critical pathway for pancreaticoduodenectomy at an academic institution--the first step in multidisciplinary team building. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:917-924.

16 Cunningham SC, Demirjian A, Schulick R. Pancreaticobiliary Surgery: General Considerations. In: Lillemoe KD, Jarnagin W, eds. Master Techniques in Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams &Wilkins; 2012.

17 Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13.

18 Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition.Surgery 2007;142:20-25.

19 Cameron JL, Sandone C. Atlas of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Vol 2/Edition 2. Singapore PMPH-USA, Limited;2014.

20 Goussous N, Patel ST, Cunningham SC. Bile-Duct Cancer. In:Cameron JL, Cameron A, eds. Current Surgicalerapy, 12th ed. New York: Mosby/Elsevier; 2016.

21 Adachi E, Harimoto N, Yamashita Y, Sakaguchi Y, Toh Y,Okamura T, et al. Pancreatic leakage test in pancreaticoduodenectomy: relation to degree of pancreatic fibrosis, pancreatic amylase level and pancreatic fistula. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi 2013;104:490-498.

22 Cho A, Yamamoto H, Kainuma O, Muto Y, Park S, Arimitsu H,et al. Performing simple and safe dunking pancreaticojejunostomy using mattress sutures in pure laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc 2014;28:315-318.

23 Abdo A, Jani N, Cunningham SC. Pancreatic duct disruption and nonoperative management: the SEALANTS approach.Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2013;12:239-243.

24 Hruban RH, Westra WH. Surgical Pathology Dissection: An Illustrated Guide. New York: Springer;2009.

25 DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Kamangar F,Winter JM, Lillemoe KD, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirtyone-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution.Ann Surg 2007;245:755-762.

26 Tian Y, Ma H, Peng Y, Li G, Yang H. Preventive effect of omental flap in pancreaticoduodenectomy against postoperative complications: a meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology 2015;62:187-189.

27 Shah OJ, Bangri SA, Singh M, Lattoo RA, Bhat MY. Omental flaps reduces complications aer pancreaticoduodenectomy.Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2015;14:313-319.

28 Choi SB, Lee JS, Kim WB, Song TJ, Suh SO, Choi SY. Efficacy of the omental roll-up technique in pancreaticojejunostomy as a strategy to prevent pancreatic fistula aer pancreaticoduodenectomy. Arch Surg 2012;147:145-150.

29 Xu B, Zhu YH, Qian MP, Shen RR, Zheng WY, Zhang YW.Braun enteroenterostomy following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1254.

30 Meng HB, Zhou B, Wu F, Xu J, Song ZS, Gong J, et al. Continuous suture of the pancreatic stump and Braun enteroenterostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:2731-2738.

31 Huang MQ, Li M, Mao JY, Tian BL. Braun enteroenterostomy reduces delayed gastric emptying: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2015;23:75-81.

32 McMillan MT, Christein JD, Callery MP, Behrman SW, Drebin JA, Kent TS, et al. Prophylactic octreotide for pancreatoduodenectomy: more harm than good? HPB (Oxford)2014;16:954-962.

33 Yang X, Patel S, Cunningham SC.e harm of prophylactic octreotide in pancreatoduodenectomy: more artefact than fact? HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:371.

34 Yang X, Kamangar F, Goussous N, Patel ST, Cunningham SC.Prophylactic octreotide for pancreatectomy: benefit or harm?Correspondence re McMillan et al 2016;264:344. Ann Surg 2017;March 10.

35 Gurusamy KS, Koti R, Fusai G, Davidson BR. Somatostatin analogues for pancreatic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4:CD008370.

36 Grobmyer SR, Kooby D, Blumgart LH, Hochwald SN. Novel pancreaticojejunostomy with a low rate of anastomotic failure-related complications. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:54-59.

February 27, 2017

Accepted after revision June 22, 2017

Author Affiliations: Department of Surgery, Saint Agnes Hospital and Cancer Center, Baltimore, MD, USA (Yang X, Aghajafari P, Goussous N,Patel ST and Cunningham SC)

Steven C Cunningham, MD, FACS, Director of Pancreatic and Hepatobiliary Surgery, Director of Research, Saint Agnes Hospital, 900 Caton Avenue, MB 207, Baltimore, MD 21229, USA (Tel: +667-234-8815; Fax: +410-719-0094; Email: Steven. Cunningham@ascension.org)

© 2017, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60053-5

Published online September 4, 2017.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Letters to the Editor

- Risk factors and managements of hemorrhage associated with pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy

- Tailored pancreatic reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-center experience of 892 cases

- Helicobacter pyloriand 17β-estradiol induce human intrahepatic biliary epithelial cell abnormal proliferation and oxidative DNA damage

- Prospective comparison of prophylactic antibiotic use between intravenous moxifloxacin and ceftriaxone for high-risk patients with post-ERCP cholangitis

- Comparative study of the effects of terlipressin versus splenectomy on liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in rats