Risk factors and managements of hemorrhage associated with pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy

2017-10-09XingLiangLiGangShiJunHaoAnAnLiuDanLeiChenXianGuiHuandChengHaoShao

Xing Liang, Li-Gang Shi, Jun Hao, An-An Liu, Dan-Lei Chen,Xian-Gui Hu and Cheng-Hao Shao

Shanghai, China

Risk factors and managements of hemorrhage associated with pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy

Xing Liang, Li-Gang Shi, Jun Hao, An-An Liu, Dan-Lei Chen,Xian-Gui Hu and Cheng-Hao Shao

Shanghai, China

BACKGROUND: Post-pancreaticoduodenectomy pancreatic fistula associated hemorrhage (PPFH) is one of the leading lethal complications. Our study was to analyze the risk factors and managements of hemorrhage associated with pancreatic fistula aer pancreaticoduodenectomy, and to evaluate treatment options.

METHOD: We analyzed 445 patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy or pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy and evaluated the relevance between clinical data and PPFH.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2017;16:537-544)

pancreatic neoplasms;

pancreaticoduodenectomy;

postoperative pancreatic fistula;

hemorrhage;

risk factors

Introduction

Pancreaticoduodenectomy and pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy are main curative treatments of periampullary neoplasms such as pancreatic head, lower bile duct, and periampullary region of the duodenum.[1]However, incidence rate of postoperative complications still remains high. Especially postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and postoperative hemorrhage are the most severe ones, which contribute to high morbidity rates. It is reported that, POPF has a high incidence of 3%-30%.[2,3]Due to unapparent symptoms and insufficient drainage, the actual incidence rate could be even higher.e incidence of postoperative hemorrhage is 5%-10%.[4-7]Although postoperative hemorrhage can involve multiple causes, POPF is confirmed as a leading cause of delayed postoperative hem-orrhage.[8-12]e mortality rate of POPF is 7.1%-23.3%,and this rate can be as high as 18%-82% if pancreatic fistula associated hemorrhage occurs.[12-14]Due to the lack of effective methods to manage the high incidence of POPF, it is important to pay more attention to the occurrence of post-pancreaticoduodenectomy pancreatic fistula associated hemorrhage (PPFH).e purpose of this study is to explore the potential risk factors of PPFH,and to summarize the experience of therapies in order to improve treatment efficacy and to decrease the incidence and mortality of PPFH.

Methods

Patients' characteristics and operating procedures

A total of 445 patients operated from January 1 to December 31 of 2013 in pancreatic surgery department of Changhai Hospital, Shanghai, were included. Among them, 209 underwent pancreaticoduodenectomies and 236 underwent pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomies. All patients received D2 lymph node dissection. Partial superior mesenteric and portal veins were resected and reconstructed if invaded. Pancreas was transected by scalpel. Pancreaticojejunostomies were all end-to-side and duct-mucosa, and a pancreatic duct stent was placed routinely. No external pancreatic or biliary drainage was performed. Polypropylene sutures(4-0) were used for the pancreaticojejunostomy, and 5-0 monofilament synthetic absorbable sutures were used for the hepaticojejunostomy. Hepaticojejunostomy was performed about 10 cm distally to pancreaticojejunostomy.End-to-side mucosa-to-mucosa double-layer gastrojejunostomy or duodenojejunostomy was performed 50 cm distally to hepaticojejunostomy. Conventional procedure was to place two peritoneal drainage tubes: one was posterior to the pancreaticojejunostomy and extended to hepaticojejunostomy, the other was placed near the pancreaticojejunostomy and extended to splenorenal area.

Perioperative management and data collection

If a patient had severe obstructive jaundice, preoperative biliary drainage would be performed by percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage. All patients received prophylactic antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers for the first 3 postoperative days and then were treated according to the symptoms. Octreotide was not used routinely aer operation. Drain fluid amylase and serum amylase were assayed 1 and 3 days aer surgeries. If patients were considered to develop pancreatic fistulas or biliary fistulas, peritoneal drainage tubes would be changed to abdominal double cannulas, so that continuous lavage and low negative pressure drainage would be performed. Laboratory parameters were evaluated in preoperative day 1 and postoperative day 3, respectively.

Definition of complications

POPF and postpancreatectomy hemorrhage were diagnosed, graded, and treated in accordance with guideline and recommendations of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF).[15,16]POPF was defined as the amylase level of drainage fluid three times greater than the upper limit of normal serum value aer postoperative day 3.e severity of POPF was graded as follows. Grade A:e fistula is transient with no clinical effect and may need a little change in management.Grade B: a change in management or adjustment of treatment is required (e.g. drain replacement because of infectious fluid or prolonged drain insertion, prolonged drain insertion because of high amylase level of drainage fluid more than 7 days even without infection, interventional drainage, antibiotics, partial or total parenteral nutrition). Grade C: the fistula is severe, life-threatening,and need special treatment or surgery.

According to the criteria of ISGPS,[16]postpancreatectomy hemorrhage was categorized as early (≤24 hours aer the operation) or late (>24 hours aer the operation), intraluminal or extraluminal, mild (hemoglobin decreases less than 3 g/dL without clinical symptoms and surgical or nonsurgical interventions are not necessary)or severe (hemoglobin decreases more than 3 g/dL with clinical symptoms, and relaparotomy or interventional angiographic therapy is needed). Based on the three criteria above, postpancreatectomy hemorrhage is graded from A to C (grade A: early mild postpancreatectomy hemorrhage; grade B: early severe postpancreatectomy hemorrhage or late mild postpancreatectomy hemorrhage; grade C: late severe postpancreatectomy hemorrhage).

In this study, PPFH was defined as postpancreatectomy hemorrhage which occurred secondary to POPF and excluded other causes (e.g. surgical relative factors, coagulation disorders).e primary mechanism of PPFH is the erosion of arteries near pancreaticojejunostomies by pancreatic enzymes and infection, or rupture of pancreatic anastomosis. And only extraluminal postpancreatectomy hemorrhage is associated with POPF, with or without intraluminal bleeding.[12,17]e grade of PPFH was consistent with the grade of postpancreatectomy hemorrhage in the following. Grade B: postpancreatectomy hemorrhage occurred mildly aer 24 hours and might not be immediately life-threatening during the mostoccasions, but might be a warning signal for later severe hemorrhage. Grade C: postpancreatectomy hemorrhage occurred aer 24 hours and was severely life-threatening,which required aggressive treatment.

Statistical analysis

Risk factors for hemorrhage secondary to pancreatic fistula aer post-pancreaticoduodenectomy were evaluated by statistical soware SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc.,IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Univariate analysis was conducted to detect potential clinical factors that would be relevant to the occurrence of PPFH using univariate ordered logistic regression analysis. Statistically significant factors in univariate analysis were introduced into the multivariable stepwise logistic regression analysis, in order to further detect independent risk factors of PPFH with the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Aerwards, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the area under ROC curve (AUC)were performed to evaluate the optimal cut-offvalues of the risk data by Youden index. Quantitative data was expressed as the mean±SD for normal distribution or as median with interquartile range for abnormal distribution. Categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers. AP<0.05 was considered statistically signif icant.

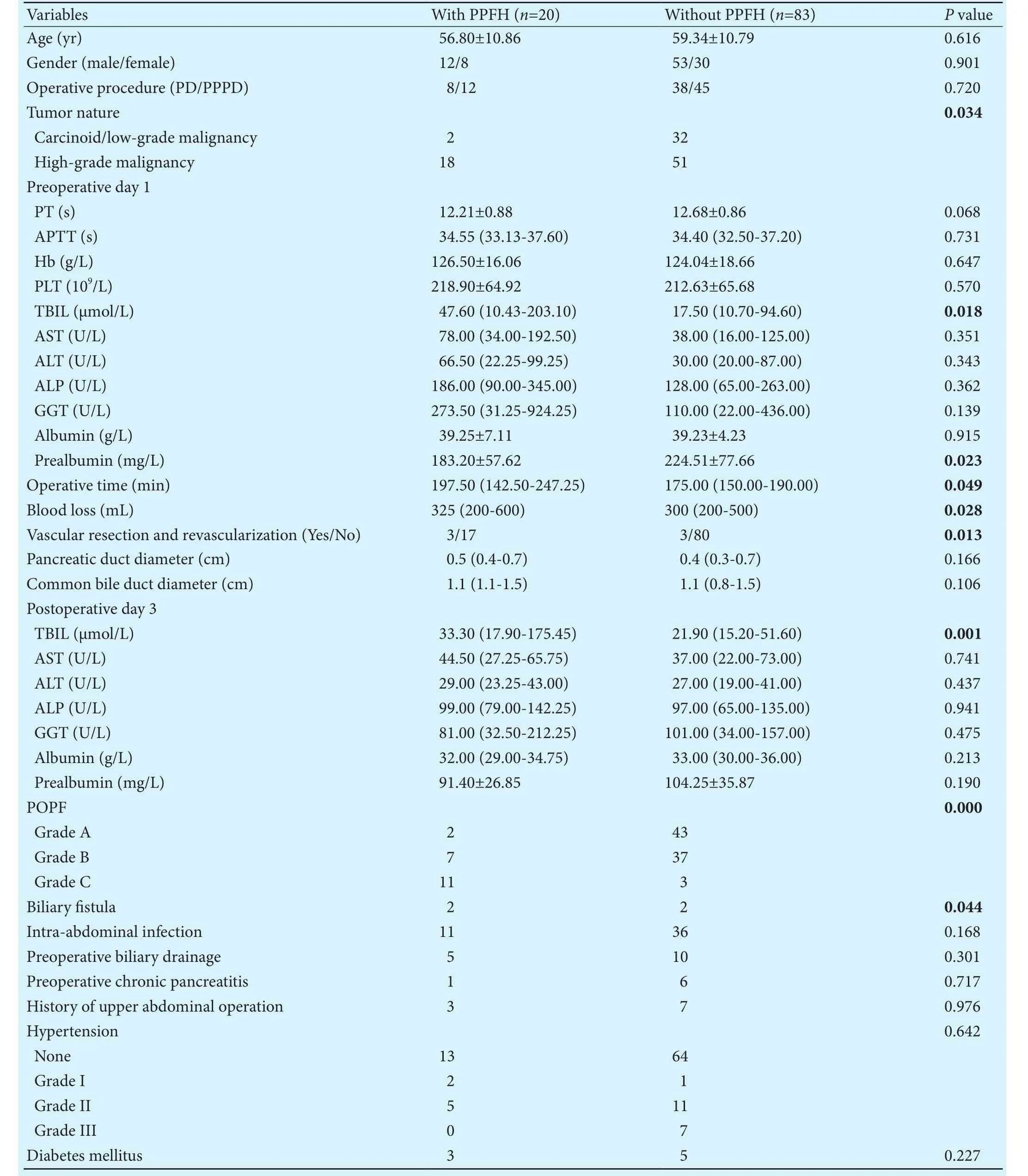

Table 1.Postoperative pathologic confirmation of 103 patients

Results

Clinical outcomes

Among the total 445 patients, 432 were cured, 13 died. A total of 122 (27.42%) developed POPF. Forty-eight cases (10.79%) were grade A, 55 (12.36%) grade B and 19(4.27%) grade C.irty-nine out of 122 POPF patients developed postpancreatectomy hemorrhage, 19 were not related to POPF and 20 were diagnosed as PPFH.e incidence rate of PPFH was 4.49% (20/445).ose with POPF unrelated hemorrhage were ruled out for further analysis.e diagnoses of the rest 103 cases were confirmed by postoperative pathology (Table 1).

Among 20 patients with PPFH, 10 were grade B and 10 grade C. Sixteen cases had only extraluminal hemorrhage (10 grade B PPFH, 6 grade C PPFH), and the rest 4 had both extraluminal and intraluminal hemorrhage(all 4 were grade C PPFH). Postoperative bleeding time was 13.4±7.6 (4-33) days.irteen patients with PPFH(65%, 13/20) were cured, while 7 (35%, 7/20) died during perioperative period, contributing to 54% (7/13) of the total death. Among 7 mortalities, 4 were extraluminal hemorrhage and 3 were both extraluminal and intraluminal hemorrhage.

Risk factors

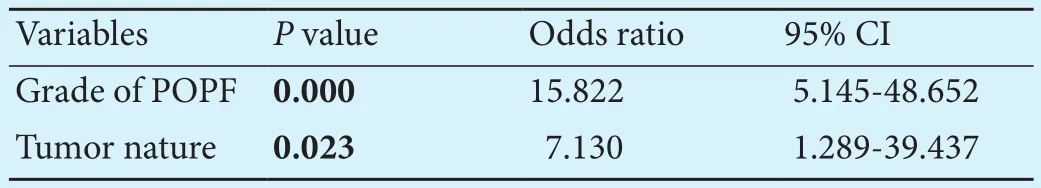

Multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis showed that the nature of tumor and the grade of POPF were the independent risk factors of PPFH (P=0.023,P<0.001, respectively; Table 3).

As shown in Fig., ROC curve indicated that, the preoperative prealbumin AUC in non-PPFH group is 0.700(P=0.007, 95% CI: 0.576-0.822).e preoperative prealbumin level ≥173 mg/L is the optimal cut-offvalue for prediction of non-PPFH (sensitivity: 76.2%, specificity:63.2%).e postoperative TBIL AUC in grade C PPFH was 0.700 (P=0.038, 95% CI: 0.509-0.891).e postoperative TBIL level ≥168 μmol/L was the optimal cut-offval-ue for prediction of grade C PPFH (sensitivity: 50.00%,specificity: 96.77%).

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of the patients and univariate analysis of risk factors for PPFH

Table 3.Multivariate analysis of independent predictive factors for PPFH

Fig.ROC curve of risk factors. A: ROC curve of preoperative prealbumin in non-PPFH group. Preoperative prealbumin AUC is 0.700 (P=0.007; 95% CI: 0.576-0.822).e preoperative prealbumin level ≥173 mg/L is the optimal cut-offvalue for prediction of non-PPFH (sensitivity: 76.2%, specificity: 63.2%). B: ROC curve of risk factors in grade C PPFH. Postoperative TBIL AUC is 0.700(P=0.038; 95% CI: 0.509-0.891). There are no significant differences in the preoperative TBIL, and blood loss.e postoperative TBIL level ≥168 μmol/L is the optimal cut-offvalue for prediction of grade C PPFH (sensitivity: 50.00%, specificity: 96.77%).

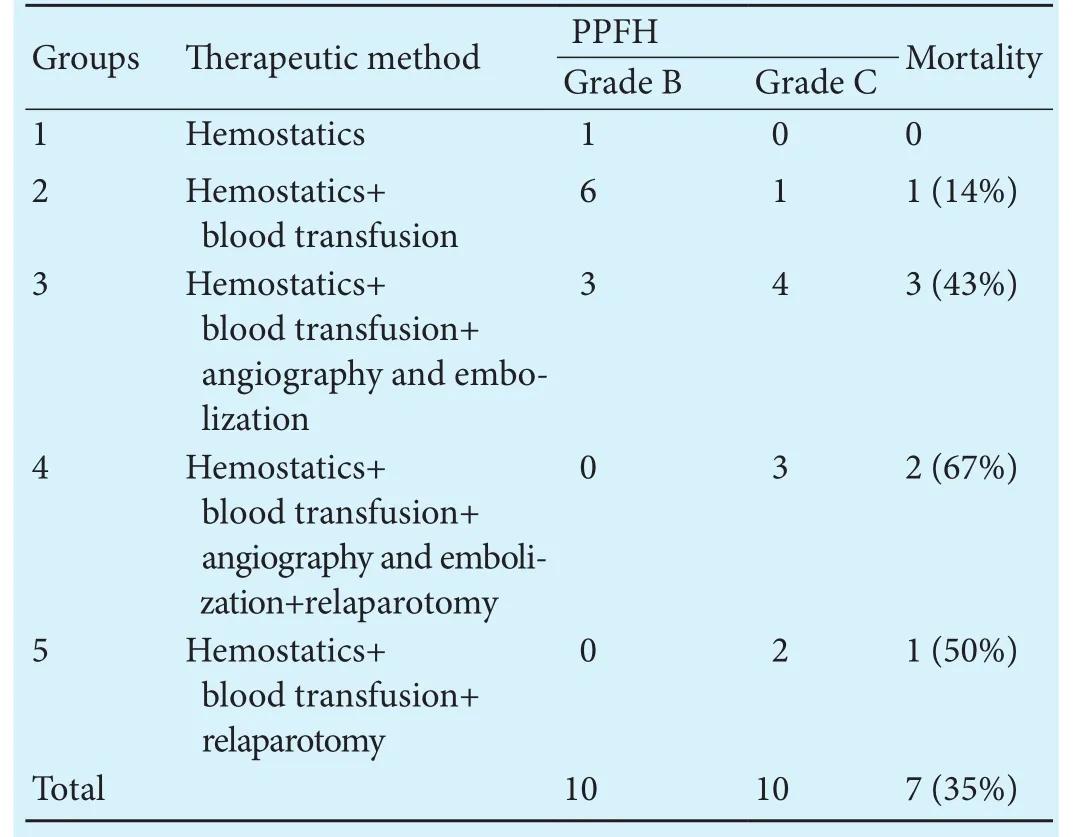

Managements

Among 12 hemorrhage cases underwent angiography-embolization or relaparotomy, four were from the branches of superior mesenteric artery, two from gastroduodenal arterial stumps, one from gastroduodenal arterial stump and pancreatic anastomosis, one from the branch of common hepatic artery, one from cholecystic arterial stump, and the rest three from pancreatic anastomosis.

Table 4.erapeutic methods and outcomes

Table 4.erapeutic methods and outcomes

External drainage placement guided by CT or B-ultrasonography were performed in group 3 and in group 5 twice, respectively. Relaparotomy includes abdominal exploration and hemostasis, reconstruction of anastomosis, and total pancreatectomy.

Groupserapeutic method PPFHMortality Grade B Grade C 1Hemostatics 1 00 2Hemostatics+blood transfusion 6 11 (14%)3Hemostatics+blood transfusion+angiography and embolization 3 43 (43%)4Hemostatics+blood transfusion+angiography and embolization+relaparotomy 0 32 (67%)5Hemostatics+blood transfusion+relaparotomy 0 21 (50%)Total10107 (35%)

Discussion

POPF incidence is high and PPFH remains a leading cause of morbidity.[11,18]e present study limited the patients with POPF to evaluate the relevance between clinical data and PPFH and thus, to reduce bias caused by nature of pancreas, anastomosis, missed diagnosis of mild pancreatic fistula, and complex operating factors.

We found that the grade of POPF and the nature of tumor were independent risk factors of PPFH. It is obvious that the severity of POPF is strongly correlated to the incidence and degree of PPFH, and this finding is consistent with previous studies.[8-10,12,19]Compared with benign or low-grade malignant tumors, high-grade malignant ones grow faster and are more likely to invade surrounding vessels, nerves, lymph nodes,[19]and therefore, more severe inflammation around pancreaslf ammation and liver function in this study.e result indicated that preoperative prealbumin was a signi ficant protective factor for PPFH. In our study, the preoperative serum prealbumin level ≥173 mg/L was the prediction of non-PPFH, indicating that if the preoperative serum prealbumin level was less than 173 mg/L, it would be of great risk of PPFH. As the sensitivity of postoperative TBIL (≥168 μmol/L) and the specificity of preoperative serum prealbumin (≥173 mg/L) for prediction of non-PPFH were not satisfactory according to AUC analysis tumors (some cases of pancreatic cancers were initially diagnosed as pancreatitis), which also need larger extent of dissection to ensure D2 resections. However, the more viscera and tissues resected, the more probably postpancreatectomy hemorrhage.[12]Especially vascular resection and revascularization increases the likelihood of vessels being corroded by pancreatic leak. Univariate analysis showed that operative time, blood loss, vascular resection and revascularization were the risk factors of PPFH.

Contrary to acute pancreatitis, patients with chronic pancreatitis before surgery have lower occurrence of POPF and PPFH.[4]is could be the result of long-term chronic pancreatitis which causes fibrosis of pancreas to be heavier, increases the diameter of pancreatic duct, and makes the texture of pancreas harder. However, our study showed no significant relationship between PPFH and chronic pancreatitis (P=0.717).is might be caused by the fact that we analyzed patients with POPF as a whole,which partially eliminated this influence.

A high level of preoperative or postoperative TBIL indicates bile duct diseases or liver dysfunction, which would be more likely to influence anastomosis healing,and even to develop a biliary fistula. Pancreatic enzymes could be activated by bile leaked to the abdominal cavity,becomes more erosive and causes heavier intra-abdominal infection, which induces PPFH.e result of univariate analysis in our study indicated that preoperative TBIL,postoperative TBIL and biliary fistula were all affiliated to the occurrence of PPFH. Our data were in consistent with those of previous studies,[12,20]especially the TBIL level was higher than 168 μmol/L at day 3 aer surgery.Moreover, 2 of 4 patients with biliary fistula developed PPFH, and their hemorrhages were both grade C. Our data indicated that the complication of biliary fistula in patients with POPF needs special attention.

When the serum albumin is lower before or aer operation, the patients are usually supplied with human albumin to 30-35 g/L.erefore, serum albumin level was not used to evaluate patients' nutritional status and liver function in our study.e level of prealbumin with a shorter half-life period was used as a more sensitive marker to estimate the patients' status of nutrition, inin this study, they can only serve as a reference. However,the combination of high postoperative TBIL level (≥168 μmol/L) and low preoperative prealbumin level (<173 mg/L) put the patient to vulnerable position of the occurrence of PPFH. More reasonable criteria to predict PPFH with single or combined indicators need future exploration.

As no predictors of PPFH had been reported before,we analyzed the preoperative day 1 and the postoperative day 3 laboratory data and tried to provide some specific parametes, and finally obtained risk factors. Although none of these factors above had significant cause-effect relations on PPFH, they were speculated significantly associated with the occurrence and the severity of PPFH according to the logistic regression analysis. Moreover,the result suggests early symptomatic treatments when a diagnosis of POPF is given without PPFH. For instance,patients with low level of preoperative serum prealbumin prefer nutritional support and hepatoprotective therapy before surgery. Extracorporeal biliary drainage placement before or during operation should be taken into consideration if patients were with high level of preoperative TBIL. If a high level of TBIL were found postoperatively, hepaticojejunostomy stenosis should be excluded, and choleretic and hepatoprotective drugs should be added. As soon as POPF occurs accompanied with biliary fistula, peritoneal drainage tubes must be kept unobstructed, and changing to abdominal double cannulas with continuous lavage and low negative pressure drainage is highly recommended. If the drainage were insufficient or unsatisfactory, CT-guided external drainage placement or even a relaparotomy for external drainage placement is preferred, especially when the POPF or the intra-abdominal infection is serious. If the tumor was high-grade malignant, especially when the vascular resection and revascularization were performed during operation, pancreatic surgeons should be more careful during perioperative period, and the dose of medicine for symptomatic treatment such as nutritional support,hemostatic and hepatoprotective should be relatively increased and octreotide would be considered as well. In addition, pancreatic texture has been demonstrated to be an independent risk factor of POPF and PPFH in many studies.[4,16,20,21]As a retrospective analysis, the subjective evaluations to pancreatic texture were quite different and could hardly be quantified.us, it was excluded in the analyses to avoid additional bias and to ensure the reliability of this study.

About 54% of the deaths was due to uncontrolled PPFH, which was the major source of mortality in this study.ree grade C PPFH patients died, whose bleedings were from both gastrointestinal tract and abdominalcavity, while 67% (4/6) extraluminal grade C PPFH patients died, indicating a more severe condition of extraluminal-intraluminal bleeding. Angiography-embolization is considered as the first choice for the diagnosis and treatment of late postoperative hemorrhage.[7,20,22,23]Even unsuccessful, it can identify the bleeding site preoperatively among about 70% cases, which help the planning of operation.[12]Ten patients were performed with angiography and embolization in this study and 5 (50%) were successful, representing a high effective rate. When PPFH was only extraluminal, the response rate of angiography and embolization was higher (63%). Extraluminal-intraluminal PPFH highly suggests the rupture of pancreatic anastomosis, which would result in more serious POPF and PPFH.erefore, in such situation, if interventional hemostasis fails, more aggressive treatments are needed.e timing of relaparotomy remains a matter of debate.us, according to the results reported here and our clinical experience, we recommend angiography as the first choice for the treatment of extraluminal PPFH. Relaparotomy should be chosen if the angiography failed, or PPFH were both intraluminal and extraluminal. Moreover, if the PPFH patient's vital signs were not stable, and cardiopulmonary arrest were likely to happen during transportation for arteriography, a reoperation for hemostasis should be performed as soon as possible.

In conclusion, our study suggested high potential malignancy, long operative time, large blood loss, performance of vascular resection and revascularization, high grade of POPF, low level of preoperative serum prealbumin, high level of both preoperative and postoperative total bilirubin and biliary fistula are notably associated with increased risk of PPFH which are fatal for patients,especially when the preoperative serum prealbumin level is lower than 173 mg/L or the postoperative TBIL level is higher than 168 μmol/L.erefore, it is crucial to pay great attention to patients with these situations during perioperative period of pancreaticoduodenectomy. Angiography-embolization is one of the major and effective therapies for PPFH. However, extraluminal-intraluminal PPFH is more serious and needs more aggressive treatments.

Contributors:LX and SLG contributed equally to this article.SCH designed and supervised the study. LX and SLG analyzed the data and wrote the first dra. HJ, HXG and SCH revised the manuscript. LAA and CDL collected the data and performed the follow-up. All authors contributed the study design and interpretation of the study and to further dras. SCH is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Brown EG, Yang A, Canter RJ, Bold RJ. Outcomes of pancreaticoduodenectomy: where should we focus our efforts on improving outcomes? JAMA Surg 2014;149:694-699.

2 Stojadinovic A, Brooks A, Hoos A, Jaques DP, Conlon KC,Brennan MF. An evidence-based approach to the surgical management of resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:954-964.

3 Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, et al. Six hundred fiy consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes.Ann Surg 1997;226:248-260.

4 Yekebas EF, Wolfram L, Cataldegirmen G, Habermann CR,Bogoevski D, Koenig AM, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: diagnosis and treatment: an analysis in 1669 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann Surg 2007;246:269-280.

5 Beyer L, Bonmardion R, Marciano S, Hartung O, Ramis O,Chabert L, et al. Results of non-operative therapy for delayed hemorrhage aer pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:922-928.

6 Eckardt AJ, Klein F, Adler A, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Warnick P,Bahra M, et al. Management and outcomes of haemorrhage aer pancreatogastrostomy versus pancreatojejunostomy. Br J Surg 2011;98:1599-1607.

7 Sanjay P, Fawzi A, Fulke JL, Kulli C, Tait IS, Zealley IA, et al.Late post pancreatectomy haemorrhage. Risk factors and modern management. JOP 2010;11:220-225.

8 Ricci C, Casadei R, Buscemi S, Minni F. Late postpancreatectomy hemorrhage aer pancreaticoduodenectomy: is it possible to recognize risk factors? JOP 2012;13:193-198.

9 Chen JF, Xu SF, Zhao W, Tian YH, Gong L, Yuan WS, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to manage post-pancreaticoduodenectomy hemorrhage. World J Surg 2015;39:509-515.

10 Lee JH, Hwang DW, Lee SY, Hwang JW, Song DK, Gwon DI,et al. Clinical features and management of pseudoaneurysmal bleeding aer pancreatoduodenectomy. Am Surg 2012;78:309-317.

11 Choi SH, Moon HJ, Heo JS, Joh JW, Kim YI. Delayed hemorrhage aer pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2004;199:186-191.

12 Wellner UF, Kulemann B, Lapshyn H, Hoeppner J, Sick O, Makowiec F, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage--incidence,treatment, and risk factors in over 1000 pancreatic resections.J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:464-475.

13 Tien YW, Lee PH, Yang CY, Ho MC, Chiu YF. Risk factors of massive bleeding related to pancreatic leak aer pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2005;201:554-559.

14 Fuks D, Piessen G, Huet E, Tavernier M, Zerbib P, Michot F, et al, Life-threatening postoperative pancreatic fistula (grade C)aer pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, prognosis, and risk factors. Am J Surg 2009;197:702-709.

15 Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13.

16 Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition.Surgery 2007;142:20-25.

17 Cullen JJ, Sarr MG, Ilstrup DM. Pancreatic anastomotic leak aer pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, significance, and management. Am J Surg 1994;168:295-298.

18 Blanc T, Cortes A, Goere D, Sibert A, Pessaux P, Belghiti J, et al.Hemorrhage aer pancreaticoduodenectomy: when is surgery still indicated? Am J Surg 2007;194:3-9.

19 Darnis B, Lebeau R, Chopin-Laly X, Adham M. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): predictors and management from a prospective database. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2013;398:441-448.

20 Roulin D, Cerantola Y, Demartines N, Schäfer M. Systematic review of delayed postoperative hemorrhage aer pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15:1055-1062.

21 You D, Jung K, Lee H, Heo J, Choi S, Choi D. Comparison of different pancreatic anastomosis techniques using the definitions of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery: a single surgeon's experience. Pancreas 2009;38:896-902.

22 Zhang J, Zhu X, Chen H, Qian HG, Leng JH, Qiu H, et al.Management of delayed post-pancreaticoduodenectomy arterial bleeding: interventional radiological treatment first. Pancreatology 2011;11:455-463.

23 Huo Y, Chi J, Zhang J, Liu W, Liu D, Li J, et al. Endovascular intervention for delayed post-pancreaticoduodenectomy hemorrhage: clinical features and outcomes of transcatheter arterial embolization and covered stent placement. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:7457-7466.

October 12, 2016

Accepted after revision April 12, 2017

Author Affiliations: Department of Pancreatic-biliary Surgery, Changzheng Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200003,China (Liang X, Shi LG, Liu AA, Chen DL and Shao CH); Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200433, China (Hao J and Hu XG)

Cheng-Hao Shao, MD, Department of Pancreatic-biliary Surgery, Changzheng Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200003, China (Tel: +86-21-81885613; Email:13801938229@163.com)

© 2017, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60061-4

Published online September 7, 2017.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Letters to the Editor

- The “Colonial Wig” pancreaticojejunostomy:zero leaks with a novel technique for reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy

- Tailored pancreatic reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-center experience of 892 cases

- Helicobacter pyloriand 17β-estradiol induce human intrahepatic biliary epithelial cell abnormal proliferation and oxidative DNA damage

- Prospective comparison of prophylactic antibiotic use between intravenous moxifloxacin and ceftriaxone for high-risk patients with post-ERCP cholangitis

- Comparative study of the effects of terlipressin versus splenectomy on liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in rats