Cost-effectiveness analysis of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization with or without sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma

2017-10-09RongCeZhaoJingZhouYongGangWeiFeiLiuKeFeiChenQiuLiandBoLi

Rong-Ce Zhao, Jing Zhou, Yong-Gang Wei, Fei Liu, Ke-Fei Chen, Qiu Li and Bo Li

Chengdu, China

Cost-effectiveness analysis of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization with or without sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma

Rong-Ce Zhao, Jing Zhou, Yong-Gang Wei, Fei Liu, Ke-Fei Chen, Qiu Li and Bo Li

Chengdu, China

BACKGROUND: Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization(TACE) and TACE in combination with sorafenib (TACE-sorafenib) have shown a significant survival benefit for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).Adopting either as a first-line therapy carries major cost and resource implications.e objective of this study was to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of TACE against TACE-sorafenib for unresectable HCC using a decision analytic model.

METHODS: A Markov cohort model was developed to compare TACE and TACE-sorafenib. Transition probabilities and utilities were obtained from systematic literature reviews, and costs were obtained from West China Hospital, Sichuan University, China. Survival benefits were reported in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).e incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated. Sensitive analysis was performed by varying potentially modifiable parameters of the model.

CONCLUSION: TACE is a more cost-effective strategy than TACE-sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable HCC.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2017;16:493-498)

hepatocellular carcinoma;

transcatheter arterial chemoembolization;

TACE in combination with sorafenib;

cost-effectiveness

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common solid malignancies globally, especially in East Asia where there is a higher prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis.[1]Curative treatments for HCC include surgical resection, liver transplantation and local ablative therapy. Although these treatments confer superior survival, only approximately 30% of patients present with early-stage tumors and undergo potentially curative therapies in practice.[2]Most HCC patients are diagnosed at Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) B (intermediate) and C (advanced) stages, and few meaningful therapeutic options are available at this point.[3]Patients with unresectable HCC (intermediate and advanced-stage disease) usually receive transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) or systemic therapies.[2]

TACE has been playing an important role in the treatment algorithm for patients with multifocal or large intrahepatic lesions who are not eligible for curative treatments.[4]Survival benefits have been proved for unresectable HCC as compared with best supportive care in several randomized controlled trials.[2,5]e median survival for patients with intermediate-stage HCC is 16.0 months without treatment, and 20.0 months with TACE therapy.[6]Two meta-analyses found that TACE significantly improved 2-year survival compared with non-active treatment for unresectable HCC, although the magnitude of the benefit is relatively small.[7,8]Nevertheless, TACE induces ischemic or hypoxic changes that result in increased vascular endothelial growth factor(VEGF) expression in the residual surviving cancerous tissue.[9]Elevations in serum VEGF are associated with poor prognosis in patients with HCC.[10]e consequent increase in angiogenesis may promote tumor growth,thereby limiting the potential for long-term disease control with TACE.

Sorafenib (Nexavar) is an oral multikinase inhibitor that restrains tumor angiogenesis and cell proliferation by way of VEGFR-2 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor. It was a standard first-line systemic agent for advanced HCC. Two randomized, multicenter, phase III trials demonstrated that sorafenib could extend the overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced HCC.[11,12]Owing to the significant antiangiogenic effect of sorafenib and the limitation of TACE, it is rational to combine TACE with sorafenib (TACE-sorafenib) to decrease post TACE angiogenesis.is is an attractive strategy to improve the efficacy of TACE therapy and potentially delay HCC progression. A phase II study using TACE-sorafenib reported a significantly longer time to progression (TTP)in patients with HCC compared to the placebo group (9.2 vs 4.9 months), with no unexpected side effects.[13]Another phase II study of TACE-sorafenib for HCC in Asia(START) indicated that this combined therapy was well tolerated and effective.[14]A systematic review concluded that the combination of TACE with sorafenib was likely to improve OS and TTP versus TACE monotherapy for the treatment of unrespectable HCC.[15]

Both TACE and TACE-sorafenib therapies have shown significant clinical benefits for unresectable HCC.However, large financial outlay is needed for treating a large number of patients with unresectable HCC.us,the decision to adopt either therapy as a first-line option carries major implications with respect to costs and expectations for quality healthcare.e aim of this study was to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of TACE alone and TACE-sorafenib therapy for treating unresectable HCC via a decision analytic model from the Chinese perspective of healthcare system.

Methods

Patients and model structure

Fig. 1.Overview of the Markov models. Simulation represents the transitions of the hypothetical cohorts through various health states from commencement of stable state to death.

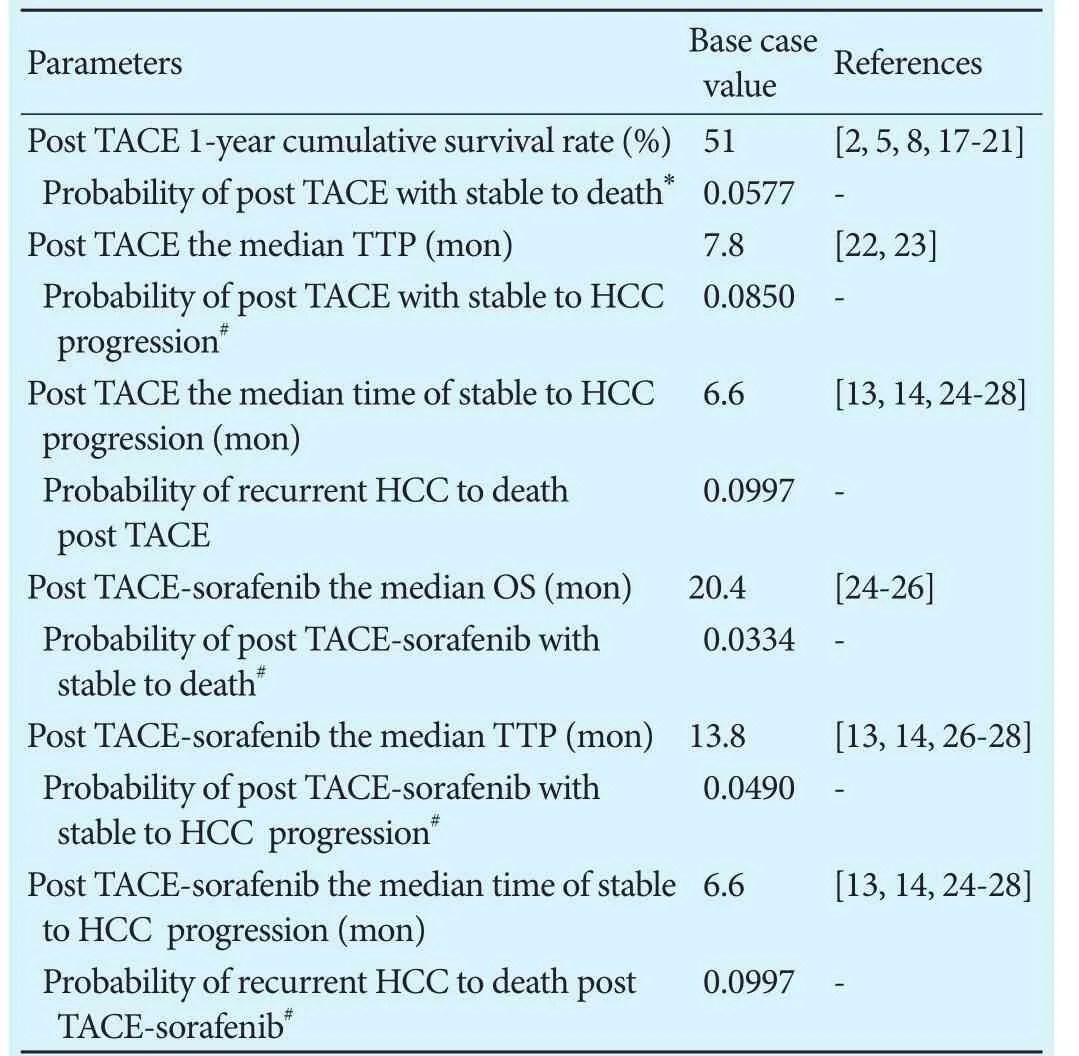

Table 1.Transition probabilities used in the model

Base case data

Similarly, all patients in the TACE-sorafenib group underwent TACE-sorafenib at outset, and were at risks of tumor progression and death. Eligible patients received TACE with interrupted dosing of sorafenib (sorafenib at a dose of 400 mg twice daily discontinued for 3 days before and 4-7 days aer TACE). TACE-sorafenib cycles were repeated every 6-8 weeks. Patients with unresectable HCC had median OS of 20.4 months[24-26]and median TTP of 13.8 months,[13,14,26-28]as well as 3.0 TACE cycles administered based on several literatures.[13,14,24-28]

Costs and utilities

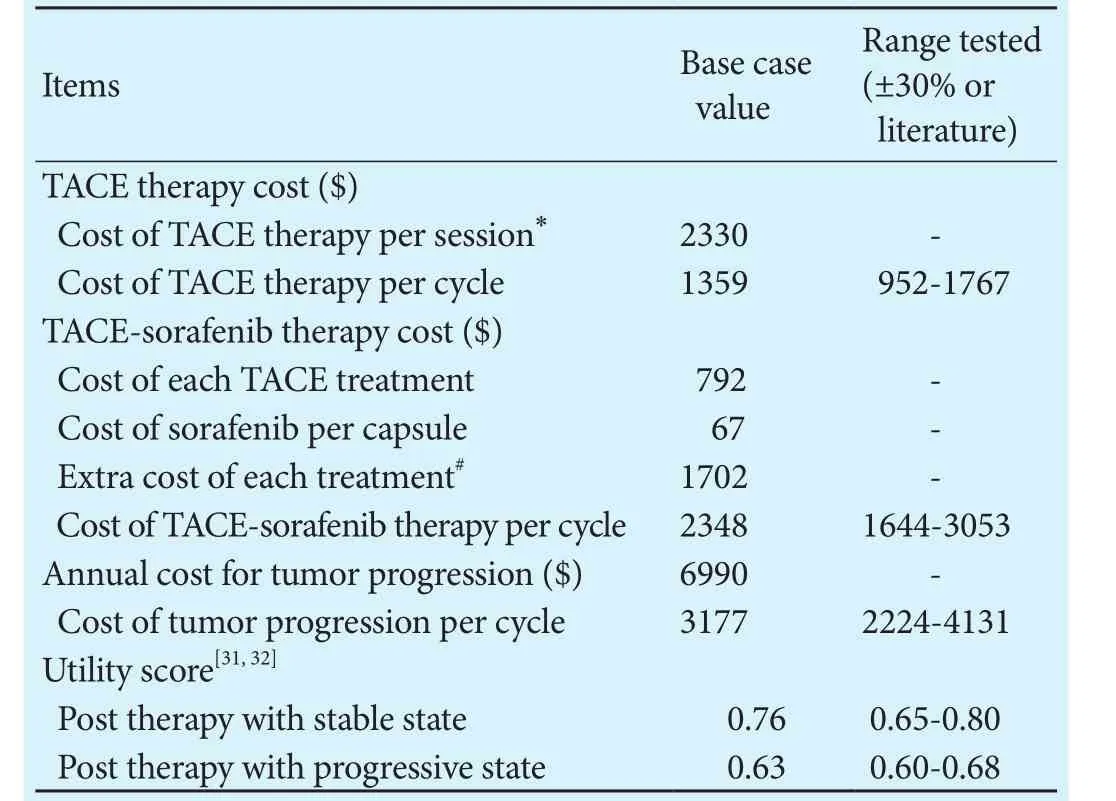

Our study was performed from the perspective of the healthcare system, and hence only direct medical costs were accounted. Estimates of direct costs (Table 2)for each health state included inpatient visit, diagnostic and laboratory testing, medications, and procedures. To obtain the cost per cycle associated with various states in the Markov chain, the itemized cost was multiplied by the frequency of its annual use and divided by the number of cycles per year. Due to the assistance program of sorafenib administered in China, patients with unresectable HCC are required to pay for sorafenib at the initial three months, and then they will receive donations until the end of their treatment. As there was no universally accepted protocol for treating tumor progression, we assumed that patients underwent a variety of therapies but had a consolidated post-progression outcome, and the total costs were equivalent to three TACE sessions.[29]All costs were converted to year 2015 U.S. dollars. Utility scores (Table 2) of each health state were derived from previously published studies (0.76 for stable state and 0.63 for progressive state).[29,30]Costs and benefits in the present study were discounted at 3% annually.[31]

Table 2.Base case value and sensitivity ranges

Sensitivity analysis

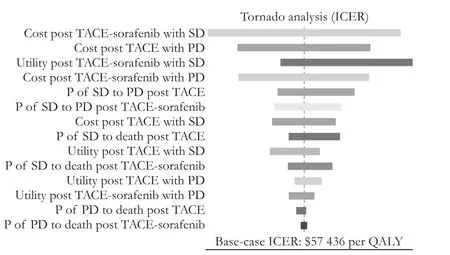

One-way sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the robustness of the economic model, and the influence of the key input parameters on the results. We propagated low- and high-input-value estimates through the models and obtained the resulting range of incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for each individual input.Tornado diagram was used to represent and assess the relative weight of each variable on overall uncertainty.

Results

Base case analysis

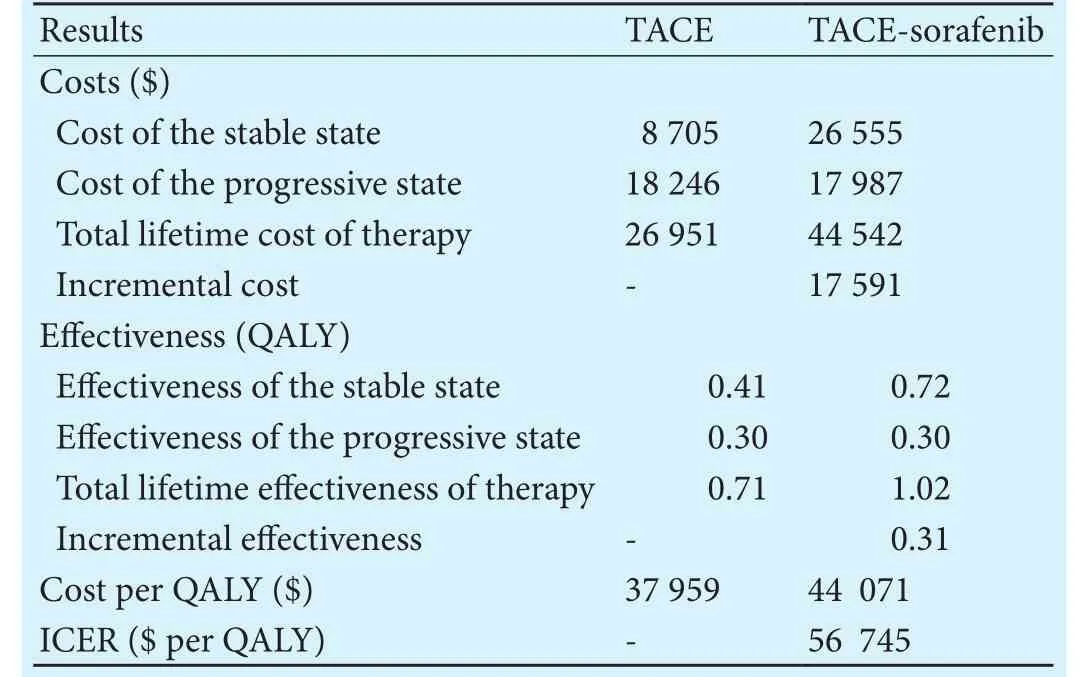

When mimicking treatment patterns in the Markov model, the costs per QALY was $37 959 for TACE and$44 071 for the combination strategy over the model time horizon. TACE-sorafenib significantly increased the cost of $17 591 to gain an additional 0.31 QALYs compared with TACE. In other words, the ICER of TACE-sorafenib versus TACE was $56 745 per QALY gained.Table 3 lists the results of cost-effectiveness analysis,which demonstrated that TACE-sorafenib would be the optimal cost-effective strategy for unresectable HCC, if we took no account of the societal willingness-to-pay(WTP) threshold.

Sensitivity analysis

Table 3.Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios comparing TACE versus TACE-sorafenib

Fig. 2.Tornado diagram of one-way sensitivity analysis for ICER.ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY: quality-adjusted life-years; SD: stable disease; PD: progressive disease; P: transition probability; TACE: transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

Discussion

A variety of therapies are employed to treat unresectable HCC, and a dramatic economic burden is produced with the treatments.us, the economic evaluation of treatments is of critical importance to address the balance between health care costs and clinical benefits, especially in a health resource limited setting. In the trial conducted by Golfieri et al,[23]the median TTP was 9 months in the TACE group, while in the START trial[14]and SOCRATES trial,[26]the median TTP of HCC patients treated with TACE-sorafenib were 13.8 months and 16.4 months, respectively.ese studies showed that TACE in combination with sorafenib achieves better effectiveness,compared with TACE monotherapy. However, TACE-sorafenib treatment also brings a heavy financial burden because of the expenses of sorafenib.[32]

Cost-effectiveness thresholds for clinical interventions vary between countries. No universal consensus of what constitutes an acceptable societal WTP is reached.It had been suggested that interventions with an ICER ofless than $20 000 per QALY are cost-effective and more than $100 000 per QALY are not, while $50 000 per QALY is used by a few influential and widely cited articles as the threshold.[33]e WTP in our study is $22 455,which is triple the per capita GDP in China, based on the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO) for cost-effectiveness analysis.[34]e ICER of TACE-sorafenib versus TACE ($56 745/QALY) was thought to be unacceptable at the WTP threshold of $22 455 from a Chinese perspective.at is to say, TACE monotherapy was a preferred cost-effective choice for patients with unresectable HCC compared with TACE-sorafenib. In addition, the major driver of the ICER of the combination therapy versus TACE was the cost post TACE-sorafenib therapy with stable state according to the one-way sensitivity analysis.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use distinct health states to account for the impact of TACE and TACE-sorafenib in managing unresectable HCC. Nowadays, several cost-effectiveness studies have analyzed various therapies for the treatment of HCC at different pathological grading stages. A study[35]demonstrated that immediate treatment with either TACE or radiofrequency ablation prevails over expectant monitoring with the intention of transplantation in patients with compensated cirrhosis and small HCC. Lim et al[29]had drawn a conclusion that in patients with HCC within the Milan criteria and Child-Pugh A/B cirrhosis, liver resection was more cost-effective than cadaveric liver transplantation. In intermediate and advanced HCC, one study[30]indicated that in daily practice dose-adjusted,but not full-dose, sorafenib is a cost-effective treatment compared to the best supportive care.

In conclusion, TACE monotherapy is a more cost-effective strategy from a Chinese perspective. Future clinical treatments should incorporate a prospective collection of costs and quality of life with limited healthcare resources. One new therapy should acquire the maximizing societal benefits and maintaining the sustainability of the country's healthcare system.

Contributors:ZRC, ZJ, LQ and LB designed and directed this research. ZRC and ZJ performed the majority of the experiments.WYG, LF and CKF collected and analyzed the data. ZRC and ZJ wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. ZRC and ZJ contributed equally to this article. LB is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:e study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A.Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87-108.

2 Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al.Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359:1734-1739.

3 Weinmann A, Koch S, Sprinzl M, Kloeckner R, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Düber C, et al. Survival analysis of proposed BCLC-B subgroups in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Liver Int 2015;35:591-600.

4 Geschwind JF, Kudo M, Marrero JA, Venook AP, Chen XP, Bronowicki JP, et al. TACE treatment in patients with sorafenib-treated unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in clini-cal practice: final analysis of GIDEON. Radiology 2016;279:630-640.

5 Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon RT, et al.Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2002;35:1164-1171.

6 Verslype C, Rosmorduc O, Rougier P; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO-ESDO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2012;23:vii41-48.

7 Li L, Tian J, Liu P, Wang X, Zhu Z. Transarterial chemoembolization combination therapy vs monotherapy in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Tumori 2016;2016:301-310.

8 Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology 2003;37:429-442.

9 Wang B, Xu H, Gao ZQ, Ning HF, Sun YQ, Cao GW. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma aer transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.Acta Radiol 2008;49:523-529.

10 Scartozzi M, Faloppi L, Svegliati Baroni G, Loretelli C, Piscaglia F, Iavarone M, et al. VEGF and VEGFR genotyping in the prediction of clinical outcome for HCC patients receiving sorafenib: the ALICE-1 study. Int J Cancer 2014;135:1247-1256.

11 Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF,et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378-390.

12 Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised,double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:25-34.

13 Sansonno D, Lauletta G, Russi S, Conteduca V, Sansonno L,Dammacco F. Transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib:a sequential therapeutic scheme for HCV-related intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized clinical trial.Oncologist 2012;17:359-366.

14 Chao Y, Chung YH, Han G, Yoon JH, Yang J, Wang J, et al.e combination of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and sorafenib is well tolerated and effective in Asian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: final results of the START trial. Int J Cancer 2015;136:1458-1467.

15 Yang M, Yuan JQ, Bai M, Han GH. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep 2014;41:6575-6582.

16 Beck JR, Kassirer JP, Pauker SG. A convenient approximation of life expectancy (the “DEALE”). I. Validation of the method.Am J Med 1982;73:883-888.

17 Lin DY, Liaw YF, Lee TY, Lai CM. Hepatic arterial embolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma--a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 1988;94:453-456.

18 Pelletier G, Roche A, Ink O, Anciaux ML, Derhy S, Rougier P,et al. A randomized trial of hepatic arterial chemoembolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 1990;11:181-184.

19 A comparison of lipiodol chemoembolization and conservative treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Groupe d'Etude et de Traitement du Carcinome Hépatocellulaire. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1256-1261.

20 Bruix J, Llovet JM, Castells A, Montañá X, Brú C, Ayuso MC,et al. Transarterial embolization versus symptomatic treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a randomized, controlled trial in a single institution. Hepatology 1998;27:1578-1583.

21 Pelletier G, Ducreux M, Gay F, Luboinski M, Hagège H, Dao T,et al. Treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with lipiodol chemoembolization: a multicenter randomized trial.Groupe CHC. J Hepatol 1998;29:129-134.

22 Lammer J, Malagari K, Vogl T, Pilleul F, Denys A, Watkinson A, et al. Prospective randomized study of doxorubicin-eluting-bead embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the PRECISION V study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010;33:41-52.

23 Golfieri R, Giampalma E, Renzulli M, Cioni R, Bargellini I,Bartolozzi C, et al. Randomised controlled trial of doxorubicin-eluting beads vs conventional chemoembolisation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2014;111:255-264.

24 Muhammad A, Dhamija M, Vidyarthi G, Amodeo D, Boyd W,Miladinovic B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of traditional chemoembolization with or without sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2013;5:364-371.

25 Qu XD, Chen CS, Wang JH, Yan ZP, Chen JM, Gong GQ, et al.e efficacy of TACE combined sorafenib in advanced stages hepatocellullar carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2012;12:263.

26 Erhardt A, Kolligs F, Dollinger M, Schott E, Wege H, Bitzer M,et al. TACE plus sorafenib for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the multicenter, phase II SOCRATES trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2014;74:947-954.

27 Yao X, Yan D, Liu D, Zeng H, Li H. Efficacy and adverse events of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in combination with sorafenib in the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol 2015;3:929-935.

28 Park JW, Koh YH, Kim HB, Kim HY, An S, Choi JI, et al. Phase II study of concurrent transarterial chemoembolization and sorafenib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:1336-1342.

29 Lim KC, Wang VW, Siddiqui FJ, Shi L, Chan ES, Oh HC, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of liver resection versus transplantation for early hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. Hepatology 2015;61:227-237.

30 Cammà C, Cabibbo G, Petta S, Enea M, Iavarone M, Grieco A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sorafenib treatment in field practice for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2013;57:1046-1054.

31 Gold M. Panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine.Med Care 1996;34:DS197-199.

32 Zhang P, Yang Y, Wen F, He X, Tang R, Du Z, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sorafenib as a first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;27:853-859.

33 Owens DK. Interpretation of cost-effectiveness analyses. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:716-717.

34 Murray CJ, Evans DB, Acharya A, Baltussen RM. Development of WHO guidelines on generalized cost-effectiveness analysis.Health Econ 2000;9:235-251.

35 Naugler WE, Sonnenberg A. Survival and cost-effectiveness analysis of competing strategies in the management of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2010;16:1186-1194.

September 2, 2016

Accepted after revision January 25, 2017

Author Affiliations: Department of Liver Surgery and Liver Transplantation Center (Zhao RC, Wei YG, Liu F, Chen KF and Li B) and Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy (Zhou J and Li Q), West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China

Prof. Bo Li, MD, Department of Liver Surgery and Liver Transplantation Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, No. 37 Guoxuexiang, Chengdu 610041, China (Tel: +86-28-85422469;Fax: +86-28-85422469; Email: cdlibo168@hotmail.com)

© 2017, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60009-2

Published online April 24, 2017.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Risk factors and managements of hemorrhage associated with pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy

- Prospective comparison of prophylactic antibiotic use between intravenous moxifloxacin and ceftriaxone for high-risk patients with post-ERCP cholangitis

- Helicobacter pyloriand 17β-estradiol induce human intrahepatic biliary epithelial cell abnormal proliferation and oxidative DNA damage

- Tailored pancreatic reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-center experience of 892 cases

- Comparative study of the effects of terlipressin versus splenectomy on liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in rats

- The “Colonial Wig” pancreaticojejunostomy:zero leaks with a novel technique for reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy