Peginterferon alfa-2a for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the era of direct-acting antivirals

2017-10-09YanHuangMingHuiLiMinHouandYaoXie

Yan Huang, Ming-Hui Li, Min Hou and Yao Xie

Beijing, China

Peginterferon alfa-2a for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the era of direct-acting antivirals

Yan Huang, Ming-Hui Li, Min Hou and Yao Xie

Beijing, China

DATA SOURCE: Relevant articles of peginterferon (PegIFN)-based treatments in HCV and sofosbuvir-based treatments, simeprevir, daclatasvir/asunaprevir, ritonavir-boosted paritaprevir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir, and grazoprevir/elbasvir,were searched in PubMed database, including general population and special population.

RESULTS: PegIFN in combination with ribavirin remains an important and relevant option for some patients, achieving SVR rates of up to 79% in genotype 1 and 89% in genotype 2 or 3 infections, which increases for patients with favorable IL28B genotypes. Triple therapy of DAA plus PegIFN/ribavirin is effective in treating difficult-to-cure patients infected with HCV genotype 3 or with resistance-associated variants.Owing to its long history in HCV management, the efficacy,tolerability and long-term outcomes associated with PegIFN alfa-2a are well established and have been validated in largescale studies and in clinical practice for many populations.Furthermore, emerging data show that IFN-induced SVR is associated with lower incidences of hepatocellular carcinoma compared with DAAs. On the contrary, novel DAAs have yet to be studied in special populations, and long-term outcomes,particularly tumor development and recurrence in patients with cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma, and reactivation of HBV in dually infected patients, are still unclear.

CONCLUSION: In this interferon-free era, PegIFN-based regimens remain a safe and effective option for selected HCV patients.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2017;16:470-479)

chronic hepatitis C;

direct-acting antivirals;

hepatitis C virus;

peginterferon alfa-2a;

ribavirin

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains a global health burden, affecting over 185 million people worldwide and causing up to 350 000 deaths yearly.[1]Prevalence is particularly and alarmingly high in Asia and over 100 million people in South Asia and East Asia are currently infected with HCV.[1]Up to 85% them become chronically infected, 15%-30% of the chronically infected individuals are predicted to develop cirrhosis within 20 years; 2%-4% of patients with cirrhosis have a risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) per year.[1]

However, a substantial proportion of patients, the majority of whom live in low-to-middle income countries, do not have access to novel curative treatments because of cost and infrastructure constraints and challeng-ing reimbursement policies; thus, these patients remain untreated and uncured. As such, PegIFN/RBV-based therapies remain important and relevant options in the era of DAAs, particularly in resource-limited settings and in specific subpopulations, and continue to be recommended as alternative regimens in major treatment guidelines.[3,4]

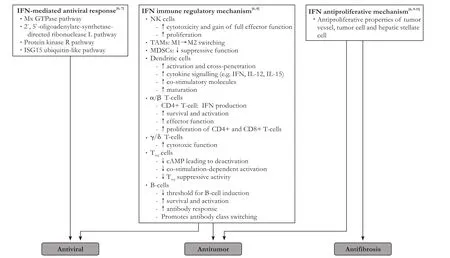

IFN mechanisms of action and pharmacokinetics

IFN-alfa is a potent immunotherapeutic antiviral agent that induces IFN-stimulated genes related to antiviral activity, lipid metabolism, apoptosis, protein degradation and inflammation.[5,6]In contrast to DAAs, IFN-alfa interacts with the adaptive and innate immune responses to promote memory T-cell proliferation, natural killer cell activation and1 cell differentiation to re-establish the1/2 balance.[5,6]e synergistic effects of IFN-alfa induce an antiviral state in infected cells. Immunomodulation by IFN-alfa through memory CD8+ T-cell regulation and alterations in major histocompatibility complex antigen expression sets up a unique immunosurveillance to control tumor growth (Fig.).[6-11]While IFN-alfa treatment has been proven to prevent the development and recurrence of HCC in HCV-infected patients,[12-15]it remains unknown whether treatment with DAAs, which are purely virus-targeting agents, can suppress HCC to a similar level.[16]

PegIFN was developed by attaching to IFN a pegylated polymer that slows subcutaneous absorption and decreases renal clearance to increase half-life and, consequently, improve efficacy and tolerability. PegIFN/RBV,rather than IFN/RBV, is recommended for the treatment of chronic HCV infection.[1]Two PegIFN molecules are commercially available: PegIFN alfa-2a and PegIFN alfa-2b. Intrinsic differences in pharmacokinetic profiles and dosing regimens exist owing to the different size and nature of the attached polyethylene glycol moiety.e branched mobile 40 kDa polyethylene glycol moiety attached to PegIFN alfa-2a shields the IFN molecule from enzymatic degradation, reducing systemic clearance and enabling once-weekly administration.e restricted volume of distribution of PegIFN alfa-2a allows standard dosing, while that of the unmodified linear 12 kDa PegIFN alfa-2b is only approximately 30% lower than for IFN-alfa, requiring weight-based dosing.e halflife of PegIFN alfa-2a is 20- and 10-fold greater than thatof IFN-alfa and PegIFN alfa-2b, respectively, allowing convenient once-weekly administration.[17,18]Resultantly,PegIFN alfa-2a achieves significantly higher SVR rates than PegIFN alfa-2b (risk ratio=1.11, 95% confidence interval: 1.04-1.19;P=0.004).[19]

Fig.Mechanisms of action of IFN-alfa. IFN: interferon; Mx: myxovirus resistance; GTPase: guanosine triphosphatase; ISG15: interferon-stimulated protein of 15 kDa; NK: natural killer; TAMs: tumor-associated macrophages; MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells;IL: interleukin; cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

PegIFN alfa-2a for the treatment of chronic HCV infection in the general population

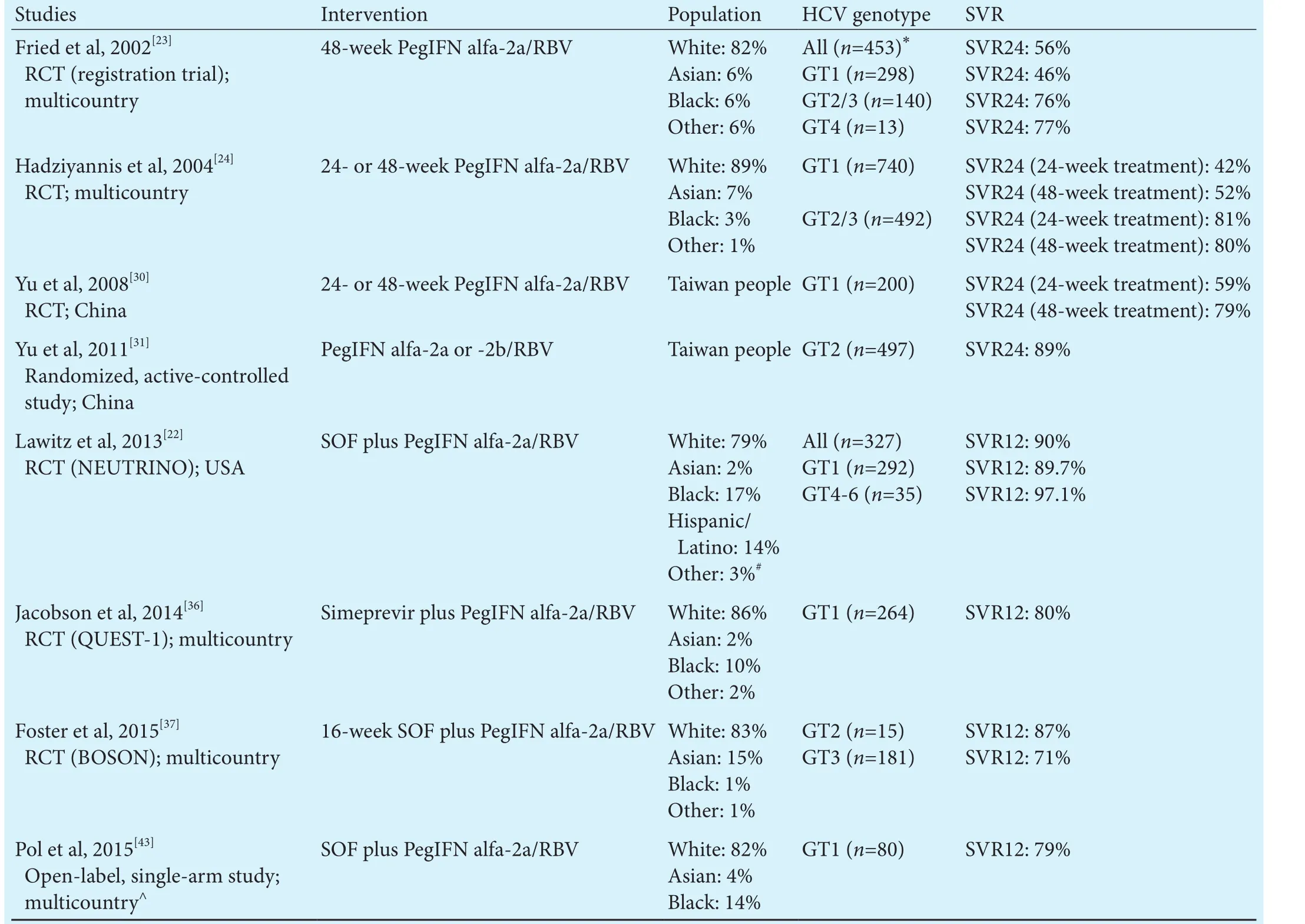

IFN-based HCV regimens have evolved since the introduction of IFN, the first available treatment, in 1986.e addition of RBV to IFN in the mid-1990s represented a major breakthrough and the standard of care changed soon aer to PegIFN/RBV as it substantially increased SVR rates. Triple therapy of DAA in combination with PegIFN/RBV became available in 2011 and significantly increased the success of IFN-based regimens by achieving SVR rates of approximately 70% with first-generation DAAs[20,21]and over 90% with newer DAAs (Table 1).[22]

PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV in easy-to-treat populations

Table 1.PegIFN alfa-2a based regimens as HCV treatment for the general population

DAAs plus PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV in difficult-to-treat populations

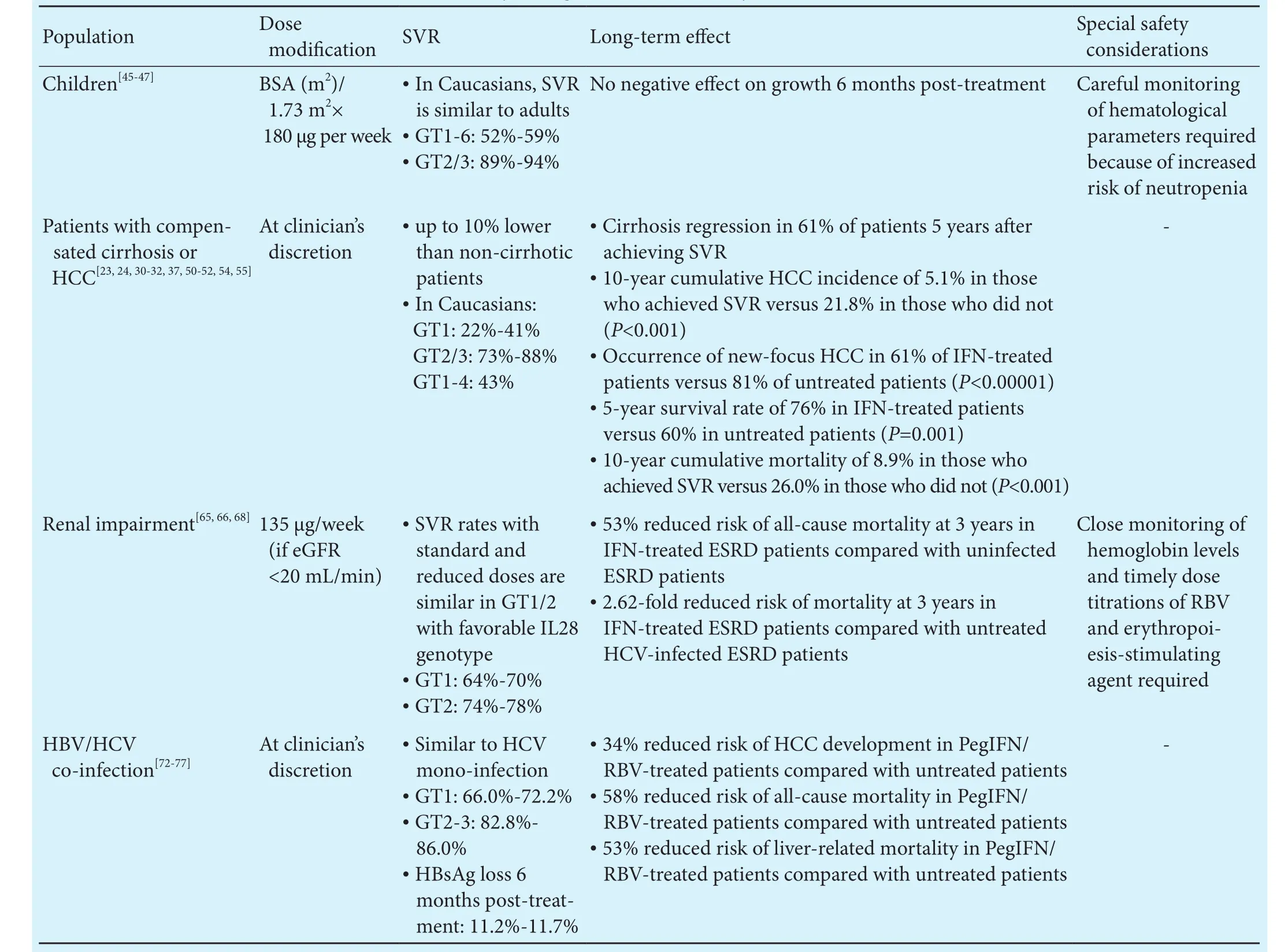

While the efficacy and tolerability profiles of PegIFN alfa-2a therapy in the general HCV-infected population are well-known, certain populations with comorbidities or distinct conditions represent unique challenges and management should be considered on a case-by-case basis that balances treatment-related benefits with risks(Table 2).

Children

Much experience has been gained with the use of IFN-based regimens in children and, at present, PegIFN/RBV remains the standard of care for this population.PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for HCV-infected children aged 5 years and older.

While steady-state trough levels of PegIFN alfa-2a are comparable in children and adults, clearance is lower in children and time to reach steady-state exposure is approximately 4-7 weeks longer than in adults.[44]As such,dose adjustments of PegIFN alfa-2a according to body surface area are necessary for children.

Similar to adults, high SVR rates can be achieved with 48-week PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV therapy in children. In children aged 3-18 years, PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV can achieve SVR rates of 52%-59% in HCV genotype 1-6 infection and 89%-94% in HCV genotype 2/3 infection.[45-47]

Dose modification or discontinuation of PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV as a result of adverse events may be required in some children.[47]Hematological parameters should be monitored as neutropenia has been observed in approximately one-third of treated children, although neutrophil counts returned to baseline levels upon treatment discontinuation.[46]Depression and other neuropsychiatric adverse events have been reported in a few IFN-treated adult patients, although these can be clinically managed aer treatment discontinuation and consultation with mental health experts. Irritability, change of mood and depression have been reported in IFN-treated pediatric patients, although rates were lower than in adults.[45,46]Single cases of suicide gesture and aggressive behavior leading to treatment discontinuation were reported over 2 years offollow-up in the PEDS-C study of pediatric patients and a single case of depression was reported over the 7-year follow-up period.[46,48]One case of new-onset type 1 diabetes was reported in the PEDS-C study anda few cases of abnormal thyroid hormone levels have been observed;[45,46]thus, children should be monitored for endocrine disorders while on IFN-based regimens.Growth effects have been reported in children while receiving PegIFN alfa-2a, follow-up data from children aged 6-17 years demonstrated that these are reversible aer treatment discontinuation without any influence on height growth.[45]

In contrast, limited data exist regarding the use of DAAs in children, and the efficacy and safety of DAAs in this population has yet to be confirmed. Only one study of DAA use in children has been published, which showed that 12-week SOF/ledipasvir treatment achieved SVR in all patients infected with HCV genotype 1 aged 12-17 years and was well tolerated.[49]While all-oral DAA regimens appear to be a promising option for treatment of HCV-infected children in the future, further data are needed before the standard treatment with IFN-based regimens can be replaced. IFN-based regimens without delay should continue to be used in selected pediatric populations such as those at high-risk of progressive liver disease and those for whom access to DAA in future is unlikely.

Table 2.Summary of PegIFN alfa-2a therapy in special populations

Patients with compensated cirrhosis or HCC

While SVR rates are generally decreased in the presence of cirrhosis, the efficacy and safety of PegIFN/RBV therapy in cirrhotic patients have been validated in large studies.[23,24,30,50-52]Furthermore, the addition of SOF to PegIFN/RBV can increase SVR rates to up to 88% in these patients.[37]

Biopsy studies demonstrated that up to 61% of patients with cirrhosis experience decreased fibrosis scores or cirrhosis regression 5 years aer achieving SVR withPegIFN alfa-2a/RBV.[32]A recent systematic review of the long-term effects of IFN-based regimens suggested that patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis treated with IFN-based therapies had better liver function tests and histology, slower liver disease progression and lower HCC incidence than non-IFN-treated patients.[53]Furthermore, those who achieved SVR with IFN-based regimens have significantly decreased 10-year cumulative mortality (8.9% versus 26.0%;P<0.001) and HCC occurrence (5.1% versus 21.8%;P<0.001) compared with non-SVR achievers.[54]

While DAAs have demonstrated higher SVR rates in patients with cirrhosis, Conti et al[57]recently reported that DAA-induced resolution of HCV infection did not reduce the incidence of HCC occurrence or recurrence.Recent real-world data from a small cohort of chronically HCV-infected, treated HCC patients in Spain showed unexpected high rate (27.6%) and pattern of tumor recurrence aer 3.5 months of all-oral DAA therapy.[58]In a large cohort of HCV-infected patients in Japan, DAA-induced SVR was associated with a more than two-fold increased risk of HCC than IFN-induced SVR (7.3% versus 3.1%).[59]Investigators from Austria observed a similar trend of increased HCC incidence with IFN-free DAA regimens compared with IFN/RBV therapy, with the authors suggesting that the increase may be due in part to the growth of malignant cells allowed by the lack of IFN activation.[60]

Postulated mechanisms of DAA-associated HCC occurrence and/or recurrence focus on deranged immunosurveillance systems caused by the rapid inhibition of HCV production by DAAs. Unlike IFN-based therapies,which maintain an effective cancer immunosurveillance status,[57,58]rapid clearance of HCV by DAAs is associated with loss of intrahepatic immune activation indicated by natural killer cells and IFN-stimulated genes, which may facilitate the growth of precancerous lesions or of small malignant cell clones.[61]

In line with recommendations from major treatment guidelines, all-oral DAA therapy is preferred in patients with compensated cirrhosis or HCC,[4,62]unless these therapies prove to be harmful in future studies. Longterm follow-up of DAA-based IFN-free treatments are currently lacking and its impact on survival and HCC occurrence and/or recurrence thus remains uncertain.erefore, more evidence will be needed before IFN-based therapies can be safely replaced by all-oral DAAs for patients with HCV-related cirrhosis and/or HCC.

Patients with severe renal impairment and/or end-stage renal disease

Owing to its large size, there is a more than 100-fold reduction in renal clearance of PegIFN alfa-2a compared with IFN-alfa.[17]e pharmacokinetic profile of 135 μg/week PegIFN alfa-2a in patients with renal impairment and/or hemodialysis is similar to that of the standard 180 μg/week dose in patients with normal renal function.[17,63,64]As such, the reduced dose can be used in patients with renal impairment.

Recent studies of HCV genotype 1/2 infected treatment-naïve patients on chronic hemodialysis showed that 64%-74% of those treated with reduced-dose PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV achieved SVR, compared with only 33%-44% of those treated with PegIFN alfa-2a monotherapy.[65,66]Patients infected with HCV genotype 1/2 receiving hemodialysis should be encouraged to receive reduced-dose PegIFN plus low-dose RBV therapy.[65,66]In acutely infected hemodialysis patients, PegIFN alfa-2a monotherapy can achieve high SVR rates (88.6%) to prevent chronic HCV infection.[67]

In HCV-infected end-stage renal disease patients,IFN-based therapies are associated with a 53% reduced risk of all-cause mortality compared with uninfected patients, while untreated HCV-infected patients had a 2.62-fold higher risk of mortality compared with treated patients, with benefits being more prominent in patients without cirrhosis or HCC.[68]

Decreased hemoglobin level is the most commonly observed adverse events in patients with renal impairment. Nevertheless, with careful patient selection, close monitoring of hemoglobin levels and timely dose titrations of RBV and erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, most of these patients can tolerate PegIFN/RBV to attain SVR successfully.[65,66]

In patients with severe renal disease (creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min) or end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, PegIFN in combination with dose-adjusted RBV at 200 mg daily remains a valid option for those at high-risk of progression who are infected with HCV genotype 2, 3, 5, or 6. In patients infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4, ritonavir-boosted paritaprevir/ombitasvir and grazoprevir/elbasvir are recommended by treatment guidelines.[4,62]However, healthcare authorities in Japan have warned against the use ritonavir-boosted paritaprevir/ombitasvir in patients with decreased renal function owing to the risk of acute renal failure.[69]Elbas-vir/grazoprevir combination is the only approved therapy for use in patients with renal impairment; unfortunately,this treatment is not yet available in Asia.

In general, limited data exist regarding the use of other DAAs in HCV-infected patients with renal impairment. Simeprevir and daclatasvir are cleared via biliary excretion and, thus, theoretically, can be used in patients with severe renal disease. However, as renal clearance is the major elimination pathway for SOF, caution is advised when using SOF-based combinations in patients with estimated creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min or with end-stage renal disease until more data become available.[4]

Patients with HBV co-infection

HBV/HCV co-infection is highly prevalent in many countries in Asia, where up to 10%-15% of all HBV-infected patients are dually infected and the prevalence of HBV/HCV co-infection reaches up to 1.7%.[70,71]

PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV has been found to be equally effective in HBV/HCV co-infection as in HCV mono-infection;[72-74]SVR rates in HCV genotype 1 are reported to be 72.2% at 6 months aer PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV therapy in dually infected patients versus 77.3% in mono-infected patients, and in HCV genotype 2/3 are 82.8%versus 84.0%, respectively.[72]Up to 11.7% and 18.5% of dually infected patients achieved HBsAg clearance at 6 months and 3.4 years, respectively, aer IFN-alfa/RBV treatment.[73,75]A long-term study demonstrated that 5 years aer PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV treatment, 97% of patients maintained SVR and 30% achieved HBsAg loss.[76]A population-based study provided evidence that in dually infected patients, treatment with PegIFN alfa-2a/RBV decreased the risk of developing HCC by 34%, allcause mortality by 58% and liver-related mortality by 53% compared with untreated patients.[77]

A report documented reappearance of HBV DNA in 38% of HBV/HCV-co-infected patients during PegIFN/RBV treatment, but there was no occurrence of hepatitis flare or clinical hepatitis.[76]A recent drug safety communication from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration reported 24 cases of HBV reactivation leading to two deaths and one liver transplantation in dually infected patients receiving DAAs.[78]As previously described, the rapid inhibition of HCV production by DAAs may derange the imumunosurveillance system and, coupled with its lack of activity against HBV, may confer increased risk of HBV reactivation in co-infected patients.[79]Close monitoring for HBV reactivation during treatment and post-treatment follow-up is needed in both IFN-based and DAA-based therapy in dually infected patients.

Conclusions

In the treatment of chronic HCV infection, PegIFN-based regimens have been extensively evaluated and have demonstrated good efficacy, both in SVR rates and in long-term outcomes, such as low incidences of HCC occurrence and recurrence, and a well-known tolerability profile, and they remain the standard of care in certain populations. In the current DAA era, PegIFN-based regimens remain an effective and safe option for many HCV-infected patients, particularly those with high likelihood of response, difficult-to-treat genotype 3,and prior DAA failures, as well as children, patients with HBV co-infection or high-risk of HCC, and other populations for whom DAAs have not yet been investigated.

Acknowledgement:We thank Hsin-Ying Huang (Shanghai Roche Pharmaceuticals Ltd.) and Stefanie Chuah (Mudskipper Business Ltd.) for writing assistance.

Contributors:XY proposed the review. HY and LMH performed articles search and wrote the first dra. HM provided further references and revised the dra. All authors contributed to the revision. HY and LMH contributed equally to the article. XY is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:Yan Huang and Min Hou are employees of Shanghai Roche Pharmaceuticals Ltd.. Minghui Li and Yao Xie have no conflict of interest to declare.

1 WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Guidelines for the screening, care and treatment of persons with hepatitis C infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 Apr.

2 Yu ML, Chuang WL. New treatments for HCV: perspective from Asia. Clin Liver Dis 2015;5:17-21.

3 Omata M, Kanda T, Wei L, Yu ML, Chuang WL, Ibrahim A,et al. APASL consensus statements and recommendation on treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatol Int 2016;10:702-726.

4 European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2016. J Hepatol 2017;66:153-194.

5 Feld JJ, Hoofnagle JH. Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature 2005;436:967-972.

6 Brassard DL, Grace MJ, Bordens RW. Interferon-alpha as an immunotherapeutic protein. J Leukoc Biol 2002;71:565-581.

7 Sadler AJ, Williams BR. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors.Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:559-568.

8 Parker BS, Rautela J, Hertzog PJ. Antitumour actions of interferons: implications for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:131-144.

9 Chang XM, Chang Y, Jia A. Effects of interferon-alpha on expression of hepatic stellate cell and transforming growth factor-beta1 and alpha-smooth muscle actin in rats with hepatic fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:2634-2636.

10 Wang L, Tang ZY, Qin LX, Wu XF, Sun HC, Xue Q, et al. Highdose and long-term therapy with interferon-alfa inhibits tumor growth and recurrence in nude mice bearing human hepatocellular carcinoma xenogras with high metastatic potential.Hepatology 2000;32:43-48.

11 Kusano H, Akiba J, Ogasawara S, Sanada S, Yasumoto M, Nakayama M, et al. Pegylated interferon-α2a inhibits proliferation of human liver cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2013;8:e83195.

12 Breitenstein S, Dimitroulis D, Petrowsky H, Puhan MA, Müllhaupt B, Clavien PA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of interferon aer curative treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with viral hepatitis. Br J Surg 2009;96:975-981.

13 Shen YC, Hsu C, Chen LT, Cheng CC, Hu FC, Cheng AL. Adjuvant interferon therapy aer curative therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): a meta-regression approach. J Hepatol 2010;52:889-894.

14 Miyake Y, Takaki A, Iwasaki Y, Yamamoto K. Meta-analysis:interferon-alpha prevents the recurrence aer curative treatment of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Viral Hepat 2010;17:287-292.

15 Liang KH, Hsu CW, Chang ML, Chen YC, Lai MW, Yeh CT.Peginterferon is superior to nucleos(t)ide analogues for prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J Infect Dis 2016;213:966-974.

16 Hiramatsu N, Oze T, Takehara T. Suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma development in hepatitis C patients given interferon-based antiviral therapy. Hepatol Res 2015;45:152-161.

17 Zeuzem S, Welsch C, Herrmann E. Pharmacokinetics of peginterferons. Semin Liver Dis 2003;23:23-28.

18 Perry CM, Jarvis B. Peginterferon-alpha-2a (40 kD): a review of its use in the management of chronic hepatitis C. Drugs 2001;61:2263-2288.

20 Poordad F, McCone J Jr, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1195-1206.

21 Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2405-2416.

22 Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1878-1887.

23 Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales flJr, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:975-982.

24 Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H Jr, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M,Marcellin P, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:346-355.

25 Chen Y, Xu HX, Wang LJ, Liu XX, Mahato RI, Zhao YR. Meta-analysis: IL28B polymorphisms predict sustained viral response in HCV patients treated with pegylated interferon-α and ribavirin. Aliment Pharmacoler 2012;36:91-103.

26 Schreiber J, Moreno C, Garcia BG, Louvet A, Trepo E, Henrion J, et al. Meta-analysis: the impact of IL28B polymorphisms on rapid and sustained virological response in HCV-2 and -3 patients. Aliment Pharmacoler 2012;36:353-362.

27 Rangnekar AS, Fontana RJ. Meta-analysis: IL-28B genotype and sustained viral clearance in HCV genotype 1 patients. Aliment Pharmacoler 2012;36:104-114.

29 Yu ML, Chuang WL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Asia:when East meets West. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;24:336- 345.

30 Yu ML, Dai CY, Huang JF, Chiu CF, Yang YH, Hou NJ, et al.Rapid virological response and treatment duration for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology 2008;47:1884-1893.

31 Yu ML, Huang CF, Huang JF, Chang NC, Yang JF, Lin ZY, et al. Role of interleukin-28B polymorphisms in the treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 2 infection in Asian patients. Hepatology 2011;53:7-13.

32 D'Ambrosio R, Aghemo A, Rumi MG, Ronchi G, Donato MF,Paradis V, et al. A morphometric and immunohistochemical study to assess the benefit of a sustained virological response in hepatitis C virus patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2012;56:532-543.

33 George SL, Bacon BR, Brunt EM, Mihindukulasuriya KL,Hoffmann J, Di Bisceglie AM. Clinical, virologic, histologic,and biochemical outcomes aer successful HCV therapy: a 5-year follow-up of 150 patients. Hepatology 2009;49:729-738.

34 Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1207-1217.

35 Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, Roberts S, et al. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2417-2428.

36 Jacobson IM, Dore GJ, Foster GR, Fried MW, Radu M, Rafalsky VV, et al. Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-1): a phase 3, randomised,double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2014;384:403-413.

37 Foster GR, Pianko S, Brown A, Forton D, Nahass RG, George J, et al. Efficacy of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin with or without peginterferon-alfa in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection and treatment-experienced patients with cirrhosis and hepatitis C virus genotype 2 infection. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1462-1470.

38 Itakura J, Kurosaki M, Higuchi M, Takada H, Nakakuki N, Itakura Y, et al. Resistance-associated NS5A variants of hepatitis C virus are susceptible to interferon-based therapy. PLoS One 2015;10:e0138060.

39 McPhee F, Suzuki Y, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, et al. High sustained virologic response to daclatasvir plus asunaprevir in elderly and cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1b without baseline NS5A polymorphisms.Adver 2015;32:637-649.

41 Peiffer KH, Sommer L, Susser S, Vermehren J, Herrmann E, Döring M, et al. Interferon lambda 4 genotypes and resis-tance-associated variants in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotypes 1 and 3. Hepatology 2016;63:63-73.

42 Lawitz E, Matusow G, DeJesus E, Yoshida EM, Felizarta F,Ghalib R, et al. Simeprevir plus sofosbuvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis: a phase 3 study (OPTIMIST-2). Hepatology 2016;64:360-369.

43 Pol S, Sulkowski MS, Hassanein T, Gane EJ, Liu L, Mo H, et al. Sofosbuvir plus pegylated interferon and ribavirin in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus in whom previous therapy with direct-acting antivirals has failed. Hepatology 2015;62:129-134.

44 Schwarz KB, Mohan P, Narkewicz MR, Molleston JP, Nash SR,Hu S, et al. Safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of peginterferon alpha2a (40 kd) in children with chronic hepatitis C. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006;43:499-505.

45 Sokal EM, Bourgois A, Stéphenne X, Silveira T, Porta G, Gardovska D, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in children and adolescents. J Hepatol 2010;52:827-831.

46 Schwarz KB, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Murray KF, Molleston JP,Haber BA, Jonas MM, et al.e combination of ribavirin and peginterferon is superior to peginterferon and placebo for children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2011;140:450-458.e1.

48 Schwarz KB, Molleston JP, Jonas MM, Wen J, Murray KF,Rosenthal P, et al. Durability of response in children treated with pegylated interferon alfa [corrected] 2a ± ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;62:93-96.

49 Balistreri WF, Murray KF, Rosenthal P, Bansal S, Lin CH,Kersey K, et al. The safety and effectiveness of ledipasvirsofosbuvir in adolescents 12-17 years old with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Hepatology 2016 Dec 20.

50 Chen X, Shang J, Yang R, Xie Q, Gao Z, Xu X, et al. High sustained virological response to optimized therapy for refractory chronic hepatitis C treatment-na(i)ve patients: a multicenter randomized study. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2015;23:412-417.

51 Rao H, Yang R, Shang J, Xu X, Chen X, Dou X, et al.e efficacy and prognostic predictors of different treatment courses with pegylated interferon α-2a and ribavirin combination in recurrent chronic hepatitis C patients. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2015;54:699-704.

52 Shang J, Xu X, Chen X, Gao Z, Gong G, Feng Y, et al. Efficacy and related factors of pegylated interferon α-2a plus ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C in non-responders. Chin J Clin Infect Dis 2015;8:232-237.

53 Hsu CS, Chao YC, Lin HH, Chen DS, Kao JH. Systematic review: impact of interferon-based therapy on HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep 2015;5:9954.

54 van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour JF, Lammert F, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA 2012;308:2584-2593.

55 Singal AK, Freeman DH Jr, Anand BS. Meta-analysis: interferon improves outcomes following ablation or resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacoler 2010;32:851-858.

56 Hagihara H, Nouso K, Kobayashi Y, Iwasaki Y, Nakamura S, Kuwaki K, et al. Effect of pegylated interferon therapy on intrahepatic recurrence aer curative treatment of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol 2011;16:210-220.

57 Conti F, Buonfiglioli F, Scuteri A, Crespi C, Bolondi L, Caraceni P, et al. Early occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol 2016;65:727-733.

58 Reig M, Mariño Z, Perelló C, Iñarrairaegui M, Ribeiro A, Lens S, et al. Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol 2016;65:719-726.

59 Toyoda H, Tada T, Takaguchi K, Senoh T, Shimada N, Hiraoka A, et al. Differences in background characteristics of patients with chronic hepatitis C who achieved sustained virologic response with interferon-free versus interferon-based therapy and the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma aer eradication of hepatitis C virus in Japan. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:472-476.

60 Kozbial K, Moser S, Schwarzer R, Laferl H, Al-Zoairy R, Stauber R, et al. Unexpected high incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients with sustained virologic response following interferon-free direct-acting antiviral treatment. J Hepatol 2016;65:856-858.

61 Serti E, Chepa-Lotrea X, Kim YJ, Keane M, Fryzek N, Liang TJ,et al. Successful interferon-free therapy of chronic hepatitis C virus infection normalizes natural killer cell function. Gastroenterology 2015;149:190-200.e2.

62 AASLD-IDSA. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C 2016 [22 February 2017]. Available from:http://www.hcvguidelines.org.

63 Barril G, Quiroga JA, Sanz P, Rodrìguez-Salvanés F, Selgas R, Carreño V. Pegylated interferon-alpha2a kinetics during experimental haemodialysis: impact of permeability and pore size of dialysers. Aliment Pharmacoler 2004;20:37-44.

64 Heathcote J, Main J. Treatment of hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat 2005;12:223-235.

65 Liu CH, Liu CJ, Huang CF, Lin JW, Dai CY, Liang CC, et al.Peginterferon alfa-2a with or without low-dose ribavirin for treatment-naive patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 2 receiving haemodialysis: a randomised trial. Gut 2015;64:303-311.

66 Liu CH, Huang CF, Liu CJ, Dai CY, Liang CC, Huang JF, et al.Pegylated interferon-α2a with or without low-dose ribavirin for treatment-naive patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 receiving hemodialysis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:729-738.

67 Liu CH, Liang CC, Liu CJ, Lin JW, Chen SI, Hung PH, et al.Pegylated interferon alfa-2a monotherapy for hemodialysis patients with acute hepatitis C. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:541-549.

68 Hsu YH, Hung PH, Muo CH, Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Kao CH. Interferon-based treatment of hepatitis C virus infection reduces all-cause mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease: an 8-year nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore)2015;94:e2113.

69 Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Summary of investigation results. Ombitasvir hydrate/paritaprevir hydrate/ritonavir. 2016. Available from: http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000212938.pdf

70 Liu CJ, Chen PJ, Chen DS. Dual chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatol Int 2009;3:517-525.

71 Konstantinou D, Deutsch M.e spectrum of HBV/HCV coinfection: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, viralinteractions and management. Ann Gastroenterol 2015;28:221-228.

72 Liu CJ, Chuang WL, Lee CM, Yu ML, Lu SN, Wu SS, et al.Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for the treatment of dual chronic infection with hepatitis B and C viruses. Gastroenterology 2009;136:496-504.e3.

73 Yeh ML, Hung CH, Huang JF, Liu CJ, Lee CM, Dai CY, et al.Long-term effect of interferon plus ribavirin on hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance in patients dually infected with hepatitis B and C viruses. PLoS One 2011;6:e20752.

74 Yeh ML, Hsieh MY, Huang CI, Huang CF, Hsieh MH, Liang PC, et al. Personalized therapy of chronic hepatitis C and B dually infected patients with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin: a randomized study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1837.

75 Yu ML, Lee CM, Chuang WL, Lu SN, Dai CY, Huang JF, et al.HBsAg profiles in patients receiving peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for the treatment of dual chronic infection with hepatitis B and C viruses. J Infect Dis 2010;202:86-92.

76 Yu ML, Lee CM, Chen CL, Chuang WL, Lu SN, Liu CH, et al.Sustained hepatitis C virus clearance and increased hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance in patients with dual chronic hepatitis C and B during posttreatment follow-up. Hepatology 2013;57:2135-2142.

77 Liu CJ, Chu YT, Shau WY, Kuo RN, Chen PJ, Lai MS. Treatment of patients with dual hepatitis C and B by peginterferon α and ribavirin reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and mortality. Gut 2014;63:506-514.

78 Administration UFaD. FDA Drug Safety Communication:FDA warns about the risk of hepatitis B reactivating in some patients treated with direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C 2016 [22 February 2017]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm522932.htm.

79 Collins JM, Raphael KL, Terry C, Cartwright EJ, Pillai A, Anania FA, et al. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation During Successful Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus With Sofosbuvir and Simeprevir. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:1304-1306.

December 20, 2016

Accepted after revision June 23, 2017

Author Affiliations: Shanghai Roche Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Shanghai 201203, China (Huang Y and Hou M); Liver Disease Center, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100015, China (Li MH and Xie Y)

Yao Xie, MD, Liver Disease Center, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100015, China (Tel: +86-10-84322284; Email: xieyao00120184@sina.com)

© 2017, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60044-4

Published online July 17, 2017.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Risk factors and managements of hemorrhage associated with pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy

- Prospective comparison of prophylactic antibiotic use between intravenous moxifloxacin and ceftriaxone for high-risk patients with post-ERCP cholangitis

- Helicobacter pyloriand 17β-estradiol induce human intrahepatic biliary epithelial cell abnormal proliferation and oxidative DNA damage

- Tailored pancreatic reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-center experience of 892 cases

- Comparative study of the effects of terlipressin versus splenectomy on liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in rats

- The “Colonial Wig” pancreaticojejunostomy:zero leaks with a novel technique for reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy