体力活动与多种类型癌症发生风险相关性及其可能机制研究进展

2017-09-29孙景权上官若男谢敏豪

孙景权,上官若男,郭 辉,谢敏豪

SUN Jing-quan1,SHANGGUAN Ruo-nan2,GUO Hui3,XIE Min-hao4

体力活动与多种类型癌症发生风险相关性及其可能机制研究进展

孙景权1,上官若男2,郭 辉3,谢敏豪4

SUN Jing-quan1,SHANGGUAN Ruo-nan2,GUO Hui3,XIE Min-hao4

癌症已经成为全世界第2大死亡诱因。研究表明,欧洲9%~19%的癌症发生率归因于体力活动不足。为了降低癌症风险,生活习惯干预(体力活动增加)可能成为一种经济且长期有效的癌症控制措施。通过在Pubmed和Highwire等网站中检索关键词“physical activity”、 “leisure-time physical activity”、“exercise”、“cancer”、“risk”、“mechanism”和“biological changes”等关键词,分析相关文献,对体力活动/运动和癌症风险之间关系以及体力活动/运动影响致癌作用的可能机制进行综述,以期为推广和提倡通过增加体力活动来预防癌症和增进健康生活方式提供理论支持。研究结果:1.无论肥胖与否,体力活动增加与多种类型癌症发生风险降低相关。2.体力活动降低癌症风险的最可能生化机制包括直接抗癌机制和间接抗癌机制,直接抗癌机制包括:代谢类激素、表观遗传学影响、氧化应激、免疫力、慢性炎症等,间接抗癌机制包括:体重降低和雌激素、脂肪因子、维生素D和阳光暴露、心理上幸福感等。研究结论:1)建议将体力活动增加作为预防癌症风险的一种有效干预措施;2)体力活动通过直接抗癌机制和间接抗癌机制降低多种癌症发生风险。

体力活动;癌症;相关性;风险

癌症已经成为全世界第2大死亡主导诱因,2012年发展中国家有800万例新癌症案例和530万例癌症相关死亡病例发生,到2030年,全球癌症负担将会双倍增加,预计将有2 170万新癌症出现和1 320万癌症死亡案例[1]。甚至,有人估计发展中国家将来癌症负担会进一步加重,而且不健康的生活方式将使这一情况雪上加霜[67]。据调查,30%缺血性疾病、27%糖尿病、21~25%乳腺癌和结直肠癌与体力活动不足有关[6]。证据表明,欧洲9%~19%的癌症发生率归因于体力活动不足[33]。体力活动不足将可能是21世纪最重要的公共健康问题之一[15]。

为了预防癌症,生活方式干预可能成为一种经济且长期有效的手段[70]。同时,增加体力活动可能成为一种降低癌症风险的潜在干预措施。一系列综述和Meta分析已经表明,体力活动被认为是预防和提高癌症存活率的有效措施。众所周知,体力活动降低心脏疾病风险和全因死亡率[12],同时降低患结肠癌、乳腺癌和子宫内膜癌的风险[68,108]。然而,体力活动是否降低其他类型癌症风险还知之甚少,这些癌症占据美国所有癌症风险的75%[7],占全世界癌症类型61%[5]。体力活动不足是非常普遍的,美国大约51%人群[3]和世界51%人群未能完成体力活动水平推荐值[40]。运动锻炼是已知的能够降低癌症发生风险的生活方式干预措施之一[13,51,52]。体力活动的增加可降低许多类型癌症患病率,这将对公共健康和癌症预防措施做出重要贡献。基于前期该领域较大量研究,笔者期望综述并分析归纳出体力活动与多种类型癌症发生风险相关性及其可能机制,以期为将增加体力活动水平作为预防癌症的措施提供理论依据。

1 体力活动与多种类型癌症发生风险的相关性

Steven C. Moore等[70]通过对12个前瞻性队列研究和144万名受试者进行Meta分析,检测休闲时间体力活动与26种癌症之间相关性,研究发现,休闲时间体力活动增加与13种癌症(食管癌、肝癌、肺癌、肾癌、胃贲门癌、子宫内膜癌、白血病、骨髓瘤、结肠癌、头颈部癌、直肠癌、膀胱癌和乳腺癌)风险降低呈现正相关,高水平体力活动与整个癌症类型风险降低7%相关;与低水平体力活动相比,高水平体力活动与7种癌症(食管腺癌、肝癌、肺癌、肾癌、胃贲门癌、子宫内膜癌和骨髓性白血病)风险负相关程度更高,并且使这些癌症风险降低≥20%;体力活动与黑色素瘤和前列腺癌风险增加相关;超重与否不影响这种相关性。这一结果表明,休闲时间体力活动可能与更多类型癌症风险降低相关,这又一次支持“休闲时间体力活动和癌症风险降低存在相关性”的观点。

1.1 体力活动增加降低乳腺癌风险

休闲体力活动增加能够降低绝经前和绝经后女性各种亚型病理性乳腺癌风险。乳腺癌是全世界妇女最常见的恶性肿瘤。大量证据表明,体力活动可降低乳腺癌风险[59,70,111]。而且,休闲时间娱乐体力活动似乎降低乳腺癌风险作用更好,运动强度至少为中等以上强度更好[32]。通常情况下,相对雌激素+/孕酮受体+的乳腺癌亚型,体力活动水平增加,降低雌激素受体-/孕酮受体-的乳腺癌亚型风险效果更好[81,111]。来源于前瞻性研究的大量证据表明,体力活动水平增加,能够降低绝经后妇女乳腺癌风险。来源于世界癌症基金会和美国癌症研究院的一个Meta分析发现,休闲娱乐体力活动每周增加7MET-hours,乳腺癌风险降低3%[9]。Pizot C等通过对38个前瞻性研究进行Meta分析发现,体力活动水平增加,降低乳腺癌风险,且这种关系不受体力活动类型、居住地、肥胖症、绝经状态和肿瘤激素受体状态影响;体力活动总量与乳腺癌风险降低存在剂量效应,静坐少动女性每周至少进行150 min大强度体力活动,将使乳腺癌风险降低9%[81]。另一研究表明,休闲娱乐活动每周增加10MET-hours就能取得类似健康受益[111]。Virginia Lope等[61]通过对1 296名西班牙女性进行流行病学研究发现,能量输出每周增加6MET-hours,绝经前妇女乳腺癌风险降低5%;绝经后妇女需要进行更多剧烈运动来获得此受益;这种健康受益对未成年妇女、激素受体阳性和HER2阳性肿瘤人群更有效;休闲时间娱乐体力活动对未生育过妇女保护效果尤其明显;相比满足国际体力活动推荐值(>3 600MET-h/周)妇女,静坐少动妇女乳腺癌风险增加71%。

1.2 体力活动增加降低胃癌风险

胃癌是全世界范围内癌症死亡的第3大主要原因和第5大流行癌症,其发病率最高地点是在东亚(主要在中国)和发展中国家[4]。Psaltopoulou T等[85]通过对1个队列研究和12个病例对照研究进行Meta分析发现,体力活动增加和胃癌风险降低之间存在正相关;与最低体力活动人群相比,最高体力活动人群胃癌风险减低19%;来源于亚洲数据显示,任何类型体力活动均能够使胃癌风险降低18%;任何类型体力活动使非贲门胃癌风险降低38%,整个类型体力活动使非贲门胃癌风险降低45%。与这一结果相似的是,Singh等[100]发现,体力活动增加使胃癌风险降低21%;Chen等[21]发现,体力活动增加使胃癌风险降低13%;Abioye等发现,体力活动增加使胃癌风险降低19%[10]。而且大部分研究证明,体力活动增加对降低非贲门胃癌风险降低具有明显的作用[10,21,100]。同时,Steven C. Moore等发现食管腺癌和胃贲门癌风险降低与体力活动增加之间存在显著相关性[70]。

1.3 体力活动增加降低结肠癌风险

Daniela Schmid等[92]通过跟踪25 753名糖尿病人群和

1.4 增加体力活动降低子宫内膜癌风险

子宫内膜癌是全球范围内第6大常见癌症。大部分研究认为,体力活动增加能够降低子宫内膜癌风险。Parkin发现,在英国,3.8%子宫内膜癌归因于体力活动低于最小推荐值[77]。通过对来源于欧洲和美国的9个队列研究(包含144万名参与者)进行汇总分析得出,休闲时间体力活动增加伴随着子宫内膜癌风险降低21%[70]。2017年,Kristin B. Borch等[17]跟踪52 370名挪威妇女,研究体力活动水平和子宫内膜癌风险发现,肥胖妇女罹患子宫内膜癌风险增高;低体力活动水平与子宫内膜癌风险发生显著正相关,并呈现剂量效应;如果将低体力活动水平(≤4,1~10级自我报告体力活动分级)增加到5~10水平,21.9%子宫内膜癌人群能够幸免。他们认为,独立于BMI,体力活动和整个子宫内膜癌及I型子宫内膜癌风险之间均存在负剂量效应,体力活动水平增加能够使21.9%的子宫内膜癌患者幸免[17]。然而,也有相反的研究结果。欧洲前瞻性研究发现:当比较体力活动活跃和不活跃妇女差异时,整个体力活动(主要包括休闲、职业和家庭体力活动)对子宫内膜癌风险不产生影响(P=0.36)[36]。一项调查护士过去几年休闲时间体力活动与健康关系的研究发现,基线休闲时间体力活动水平与子宫内膜癌风险无关,但是,每周快走时间≥3h与子宫内膜癌风险呈现显著负相关[28]。体力活动是否降低子宫内膜癌风险的研究结果不一致性的可能原因是,各个文献中所用体力活动评价方法不一样(自我报告问卷、采访等);体力活动类型(休闲娱乐、职业的、交通和家务);体力活动强度、频率、时间;检测体力活动时间点;以及不同数据统计方法。尽管目前研究结果不一致,但是,基于体力活动能够影响内分泌激素水平、胰岛素介导信号通路和维持能量平衡的机制,因此,建议通过增加体力活动来减少子宫内膜癌风险。

1.5 体力活动增加对前列腺癌风险的影响

前列腺癌的发病率和死亡率仅次于肺癌,它是全世界男性易发第2大癌症。目前关于体力活动和前列腺癌风险之间相关性的研究结果不一致。有研究显示,休闲时间体力活动与前列腺癌风险呈现正相关[70],但是,目前还没有生物学机制来解释这一关系。其原因可能是,体力活动活跃男性更可能受到数字直肠检查和/或前列腺特异性抗原筛查,增加其被诊断为前列腺癌的可能性[71]。

另外,研究者同时分析了前列腺晚期癌症与体力活动之间相关性,发现体力活动与晚期前列腺癌风险之间不存在相关性[70]。Markozannes G等通过对248篇文献进行Meta分析(1 907名受试者其中115个队列研究数据)得出,体力活动与任何类型前列腺癌风险之间没有相关性,或者体力活动对前列腺癌风险没有较大影响,影响前列腺癌风险因素包括身高和BMI[65]。

但是,也有研究显示,体力活动降低前列腺癌风险。Roy J. Shephard[97]对1996—2016年6月发表的 85篇关于体力活动与前列腺癌风险文献进行综述发现,7篇报道体力活动增加前列腺癌风险;31篇报道两者之间无明显相关;21篇报道体力活动有降低前列腺癌风险的趋势;21篇报道体力活动显著降低前列腺癌风险(降低10%~30%或者更多);相对娱乐性体力活动,职业体力活动降低前列腺癌风险结果较为明显;相对小或者中等强度活动,大强度活动降低前列腺癌风险效果最好;同时发现,体力活动与前列腺癌风险之间存在剂量效应。Roy J. Shephard[97]认为,青少年和成年早期似乎是预防前列腺癌的最佳年龄;尽管规律体力活动和前列腺癌风险降低之间关系有待于证实,但是,大部分研究已经发现,体力活动能够给机体带来明显受益,因此,体力活动增加仍然是被推荐用于预防前列腺癌的有效措施。

1.6 体力活动增加可能增加罹患黑色素瘤风险

Steven C. Moore等发现,休闲时间体力活动水平增加伴随着黑色素瘤风险增加[70]。然而,也有不同的研究结果,一个病例对照研究发现,较高体力活动水平伴随着黑色素瘤风险降低30%[98]。这两个研究结果是不一致的。较多机会的太阳暴露似乎是黑色素瘤风险增加最可能的原因,因为体力活动经常是穿着较薄衣服并且在户外进行,同时也伴随晒伤几率的增加[44]。另外,Steven C. Moore等[70]发现,在高紫外线地区,体力活动与黑色素瘤相关程度更高,这推断出太阳暴露是这一关系的重要诱因。体力活动活跃者呈现出是黑色素瘤易发人群,因此,应该加强太阳暴露防护措施。

1.7 体力活动与其他类型癌症关系

对于肾癌和膀胱癌来说,尽管Steven C. Moore等发现,它们发生风险与体力活动之间存在显著负相关,但是,其他Meta分析认为,两者之间不存在显著性相关。对于骨髓性白血病和骨髓瘤来说,尽管Steven C. Moore等发现它们发生风险与体力活动之间存在明显负相关[70],然而2015年一篇Meta分析认为,两者不存在相关[49]。对于肝癌来说,Behrens G研究[14]和Steven C. Moore等[70]均发现其发生风险与体力活动存在负相关,但是,目前这方面研究较少,需要额外大量数据进一步确认。尽管Steven C. Moore等[70]发现胆囊癌和小肠癌与体力活动之间具有非常显著负相关,但是,其他研究发现两者之间不存在相关[14,24]。

1.8 BMI是否影响体力活动与癌症风险的相关性?

体力活动增加往往伴随BMI降低,那么BMI是否会影响体力活动和癌症风险之间的相关性呢?纵向研究[41,58]表明,运动锻炼/体力活动帮助控制体重和降低癌症相关标志物(如雌二醇)含量,其最可能原因是,得益于体重降低[19,35]。这些研究结果得出的观点是,“体力活动主要是通过体重降低来降低癌症风险”。然而,Steven C. Moore等发现,体力活动和大多数类型癌症之间的相关性不依赖于BMI[70]。目前发现,对于食管腺癌以及肥胖相关癌症(如肝癌、胃贲门癌、肾癌和子宫内膜癌)[88]来说,它们与体力活动之间关系稍微依赖于BMI,BMI可能是作为一种调节物质解释体力活动与这些癌症风险降低有关的原因。另外,Steven C. Moore等[70]发现,对于BMI≤25的人群来说,休闲体力活动与子宫内膜癌无相关性。这可能反映出当去除体重因素后,体力活动和癌症风险之间关系不存在。对于其它类型癌症人群来说,几乎没有证据显示BMI存在影响,这表明对于超重和肥胖人群,更高的体力活动水平仍然伴随较低的癌症风险。这一点是重要的,因为并不是所有高水平体力活动人群都具有较低体重,这可能将有助于鼓励超重或是肥胖人群成为体力活动活跃人群。

表1 体力活动与多种类型癌症发生风险相关性文献汇总Table 1 The Literature Summary of the Association between Physical Activity and Risk of Many Types of Cancer Related Literature

续表

2 体力活动增加降低癌症风险的生物学可能机制

由上述可知,运动锻炼或者体力活动增加与多种类型癌症发生风险呈负相关。同时,运动锻炼对癌症人群的健康受益仍然存在。观察性队列研究表明,已确诊癌症人群进行规律性锻炼(如工作时间体力活动或者是家务体力活动)后,其复发率或者癌症特异性死亡率显著降低[8]。在一个前瞻性队列研究中,研究者对41 528名参与者进行调查发现,运动锻炼使癌症特异性死亡风险降低48%[43]。但是,运动抗癌作用的具体机制目前还不十分清楚。更多研究应该集中于探究体力活动和致癌作用之间关系的机制是什么,这将进一步帮助鉴定出运动抗癌作用特异性分子靶点,从而有针对性进行干预[67]。目前,体力活动/运动锻炼可能是通过间接或/和直接生物学机制来影响致癌通路。

2.1 体力活动直接的抗癌通路

运动锻炼后身体内有许多直接生物学、表观遗产学、代谢学和炎症因子的改变[8]。这些改变是体力活动增加降低癌症风险的直接抗癌通路。下面汇总连接体力活动和癌症风险之间最有可能的机制(无重要程度顺序之分):

胰岛素样生长因子(Insulin-like growth factor,IGF-1)等代谢类激素:IGF-1绑定其受体络氨酸激酶后,激活许多信号通路,进而抑制细胞凋亡、促进细胞生长和血管生成[62]。高水平IGF-1将促进肿瘤细胞生长并伴随着癌症发生率升高[91]。已经证明运动锻炼能够降低IGF-1含量。进行递增强度自行车运动60 min后,男性运动员血浆表现出抑制肿瘤细胞株LNCaP生长的作用,其主要原因是运动后血液中IGF-1水平降低、IGFBP-1水平和表皮生长因子浓度增加[90]。研究发现,体力活动活跃癌症人群的IGF-1水平降低并伴随着生存改善[47]。Dieli-Conwright等[27]认为,体力活动通过降低脂肪含量和增加骨骼肌功能,进而降低胰岛素、IGF-1、可利用雌激素和瘦素含量,最终达到降低乳腺癌风险的效果。IGF-1信号通路介导运动/体力活动抗癌可能机制详见图1。

表观遗传学对基因表达、DNA修复和端粒长度影响:运动通过改变染色体的表观遗传学生化变化来影响遗传基因表型表达,例如,组蛋白修饰、DNA甲基化、microRNA表达和染色质结构变化等[74]。一个以前列腺癌低风险男性为研究对象的前瞻性研究发现,一个以运动为主的生活方式改变计划能够降低一系列RAS家族的致癌基因(RAN、RAB14和RAB8A)表达[76]。在前列腺中,RAN(ras相关核蛋白)可能作为一个雄性激素受体共激活剂发挥作用,同时在肿瘤组织中表达量增加[76]。因此,运动锻炼可降低致癌基因表达。对运动锻炼敏感基因还涉及到细胞循环和DNA修复支持,包括通过组蛋白脱乙酰酶和micRNA通路发挥作用的BRCA1和BRCA2[78]。另外,运动对端粒具有表观遗传学作用,它是通过避免端粒转录错误实现的[74]。在一个临床研究中,对于患有早期前列腺癌人群来说,规律锻炼和健康饮食能够增加端粒长度和降低前列腺特异性抗原进程[75]。

图1 胰岛素样生长因子信号通路介导运动/体力活动和癌症风险可能机制Figure 1. The Possible Mechanism of Insulin-like Growth Factor Signal Pathway Mediated the Association between Exercise / Physical Activity and Cancer Risk

血管活性肠肽(Vasoactive intestinal peptide,VIP):VIP是一种神经肽,它能够增加人类乳腺癌和前列腺癌细胞株的增殖、存活、雄激素抵抗和去分化[105,112]。一次性运动后血浆中VIP暂时性增加[112]。这一增加诱发抗VIP抗体增加,这也解释了规律锻炼人群具有较低VIP滴定量的原因[106]。研究证实,与无癌症大众人群相比,罹患乳腺癌和前列腺癌人群的VIP滴定量升高[106]。运动锻炼能够增加VIP抗体含量,从而降低VIP滴定量,达到抗癌作用(图2)。

氧化应激和抗氧化通路:越来越多证据表明,氧化应激在人类多种类型癌症发生过程中起着重要作用。机体对规律性运动的适应性反应是抗氧化能力增强。运动尤其是高强度运动产生ROS,机体对ROS增加的适应性变化是抗氧化基因上调,进而导致抗氧化酶(如超氧化物歧化酶、谷胱甘肽和过氧化氢酶)产量增加。加利福尼亚州大学一项研究发现,相对体力活动较少人群,每周进行≥3h大强度体力活动男性的正常前列腺中核因子相关因子-2(nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2,Nrf-2)表达增加,Nrf2蛋白刺激抗氧化酶表达,并激活其它保护基因[64]。F2-异前列腺素和8-羟基去氧鸟苷是癌症病因学中观察到的DNA氧化损伤标志物。研究表明,体力活动增加显著降低F2异前列腺素和8-羟基去氧鸟苷含量[20,104]。肿瘤细胞及其周围肿瘤间质细胞中氧化应激程度降低可能对预防肿瘤进程和转移起到保护作用[101]。运动锻炼通过增加抗氧化酶活性从而发挥抗癌作用可能机制详见图3。

图2 体力活动增加通过降低VIP滴定量发挥抗癌作用可能机制Figure 2. The Possible Mechanism of Increased Physical Activity by Reducing the VIP Titres to Exert Anticancer Effect

图3 体力活动增加通过增加抗氧化酶活性发挥抗癌作用可能机制Figure 3. The Possible Mechanism of Increased Physical Activity by Increasing the Activity of Antioxidant Enzyme to Exert Anticancer Effect

热休克蛋白(Heat shock proteins,HSPs):运动后体内热休克蛋白含量增加,尤其是大强度无氧运动后其升高幅度更大[23]。HSP增加是运动锻炼保护体力活动活跃乳腺癌人群心脏的可能机制[95]。HPS增加也是运动降低化疗人群认知损害的机制,其通过保护大脑中星形胶质细胞和支持细胞来发挥作用[18]。然而,HSP在运动锻炼抗癌方面具有潜在缺陷。研究发现,在多种类型癌症中,HSP显著高表达[23],而且一些癌症组织存活甚至依赖于HSP[72]。因此,运动诱发HSP增加是否保护癌症人群目前还不确定。因此,建议癌症人群(无运动锻炼习惯)在化疗前和即刻,进行无氧锻炼是否是合适的,还需要进一步研究证实。

鸢尾素:它是I型转膜信使蛋白,运动引起骨骼肌收缩诱发鸢尾素产生[2]。研究表明,高水平鸢尾素与乳腺癌良好预后呈正相关[84]。鸢尾素能够显著降低恶性肿瘤细胞增殖、转移和生存,而对良性癌细胞无此影响[37]。

免疫力:运动过程中儿茶酚胺类增多,促进白细胞在血液中募集,导致中性粒白细胞、淋巴细胞和单核细胞(包括自然杀伤细胞、CD4+T细胞和B细胞)浓度增加,最终提高免疫系统监管癌症细胞的能力[107]。大多数研究表明,中等强度,尤其是规律性锻炼能够改善所有年龄段人群的免疫功能[86]。体力活动降低乳腺癌风险可能机制是,规律性中等强度运动能够提高自然杀伤细胞数量和功能,进而提高攻击癌细胞和抑制肿瘤生长的能力[61]。

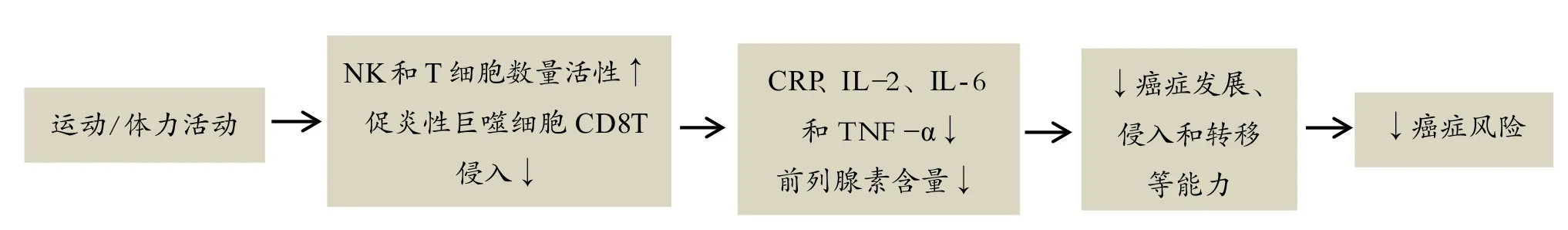

慢性炎症和前列腺素:研究发现高水平炎症标志物与癌症风险和癌症特异性死亡风险增加呈现正相关[102,110]。IL-1、IL-6、TNF-α和CRP是与乳腺癌相关的炎症因子标志物。运动锻炼具有抗炎症作用。运动增强NK细胞活性和增加T细胞产量,最终达到降低炎症因子作用[86,114]。分析人体运动后外周血液成分发现,运动后血液中CRP、IL-2、IL-6和TNF-α含量降低[34,39]。另外,研究发现,凋亡相关speck-样蛋白(包括半胱天冬酶募集域,caspase recruitment domain,ASC)调节炎症通路,ASC激活ILs、TNF和其他炎症因子释放[96]。规律运动上调ASC甲基化,导致人体单核细胞基因活性降低[74]。同时,Kawanishi等小鼠实验发现,运动训练通过抑制促炎性巨噬细胞和CD8T侵入,从而降低脂肪组织中炎症因子含量[50]。长期过度产生高水平前列腺素(通过激活COX-2)与癌症进程、细胞凋亡、入侵、血管生成和转移有关。中等强度、规律的和无创伤性运动锻炼降低血清前列腺素含量。休闲时间体力活动与前列腺素-2浓度呈现负相关,体力活动从5.2增加到27.7 MET-hours/周,前列腺素-2含量降低28%[66]。因此,运动锻炼能够通过降低炎症因子来发挥抗癌作用(图4)。

图4 体力活动增加通过降低炎症因子含量发挥抗癌作用可能机制Figure 4. The Possible Mechanism of Increased Physical Activity by Reducing the Content of Inflammatory Factor to Exert Anticancer Effect

能量代谢和胰岛素抵抗:近来研究发现,运动锻炼降低乳腺癌人群血清中胰岛素含量和增加胰岛素敏感性。高胰岛素血症、高血糖症和胰岛素抵抗伴随癌症风险增加、预后较差和前列腺癌男性治疗后高复发风险[30,62,110]。因此,运动锻炼可能是通过改善胰岛素代谢降低癌症风险。

2.2 体力活动间接的抗癌通路

许多间接因素贡献于体力活动带来的抗癌受益。这些间接因素包括:体重降低、瘦素、脂联素、雌激素、炎症标志物、阳光暴露(维生素D和生理节律)和心情愉悦。

表2 体力活动/运动锻炼发挥抗癌作用的主要间接生物分子或通路汇总[103]Table 2 Mainly Indirect Biological Benefits of Physical Activity/Exercise to Exert the Anticancer Effect[103]

雌激素、肥胖和体重降低效果:2002年,乳腺癌研究团队对关于绝经后妇女内源性激素和乳腺癌风险关系的前瞻性研究重新整合和分析后发现,乳腺癌风险增加伴随所有性激素含量显著升高,如总雌二醇、游离雌二醇和非SHBG绑定含量[53]。SHBG浓度与性激素生物利用度相关,因此,其是疾病发生的风险因素[31]。雌激素通过促进自由基产生,引起基因毒性进而起到致癌作用[56]。运动锻炼帮助降低体重。体重降低导致血清性激素和瘦素水平降低[35]。另外证据表明,在体重降低之前,运动能够直接降低血清雌激素水平,而不依赖于体重降低[55]。一个临床研究显示,每进行100 min运动,血清雌激素含量降低3.6%[94]。Emaus等对204名绝经前妇女研究发现,高水平休闲娱乐体力活动妇女的雌二醇含量较低[29]。而对于绝经后妇女来说,体力活动增加与雌激素显著降低和SHBG增加相关,同时,伴随乳腺癌风险降低[35]。另外,运动和控制饮食可帮助改善体重和降低血清甘油三酯、总胆固醇和改善高密度脂蛋白/低密度脂蛋白[94]。流行病学研究表明,血液中高水平胆固醇与癌症风险和进程相关[82]。体力活动通过改善体重、甘油三酯和雌激素含量,达到降低癌症风险机制简图详见图5。

图5 体力活动通过改善体重、甘油三酯和雌激素含量达到降低癌症风险机制Figure 5. The Abbreviated Drawing of the Mechanism of Increased Physical Activity by Improving Body Weight,the Levels of Triglycerides and Estrogen to Reduce Cancer Risk

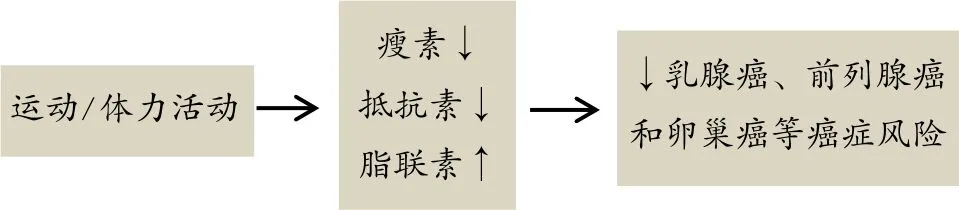

脂肪因子:脂肪组织是一个内分泌器官,其分泌脂联素、瘦素、抵抗素和其他细胞因子。研究证实,瘦素是直接和独立的诱发乳腺癌的因素,其通过雌激素和胰岛素信号通路,增强血管生成和细胞增殖[93],这一机制解释了高水平瘦素与激素相关癌症(如乳腺癌、前列腺癌和卵巢癌)之间存在的正相关关系[73]。相反的,血浆脂联素水平与肥胖、乳腺癌和前列腺癌风险呈现负相关,这最可能与脂联素具有抗炎症特性有关[16]。而且,脂联素也能抑制一氧化氮酶失活,从而降低肿瘤细胞诱发的血小板聚集[89]。肿瘤细胞诱发血小板聚集,进而依附血小板,达到“隐身”效果,而增加癌细胞转移,从而保护癌细胞不被NK-细胞杀死[38]。抵抗素能够增加乳腺癌风险,乳腺癌人群中血清抵抗素水平显著升高。与淋巴结未转移人群相比,淋巴结转移人群抵抗素含量显著增高,这可能促进肿瘤细胞转移[45]。由上可知,脂联素水平降低、瘦素和抵抗素水平升高与乳腺癌风险增加相关[45,48]。而规律性运动能够增加血液脂联素水平和降低瘦素水平[39]。抗阻训练也能显著升高血清脂联素水平和降低瘦素含量[26]。因此,体力活动增加通过改善脂肪因子含量达到降低癌症风险的机制如图6所示。

图6 体力活动增加通过改善脂肪因子含量降低癌症风险机制Figure 6. The Abbreviated Drawing of the Mechanism of Increased Physical Activity by Improving the Levels of Adipocytokines to Reduce Cancer Risk

维生素D水平和阳光暴露:定期合理阳光暴露,通过保持充足血浆维生素D水平起到抗癌作用[22]。高水平维生素D伴随着大肠癌、乳腺癌和前列腺癌死亡率降低[69,79,113]。另外研究发现,阳光暴露与前列腺癌风险降低相关且不依赖于维生素D[63]。

心理上幸福感:心理上沮丧、焦虑和苦恼降低癌症人群成活率。一个大样本(41 000名前列腺癌人群)的前瞻性队列研究表明,相对无沮丧男性,心理上沮丧男性的疾病-特异性存活率降低25%[83]。另外,一个关于头颈部癌症研究发现类似结果[54]。已证明,规律性运动锻炼帮助改善心情、降低焦虑和恐惧感[80,87]。Liu等发现,较高频率的身体锻炼与癌症人群心理压力改善呈显著正相关[60]。目前,运动帮助对抗沮丧的机制还不清楚,但可能的假设是,运动增加脑啡肽和单胺类释放、分散注意力、升高核心区域温度和增加医疗干预措施依从性[54,83]。另外,Ruas及其同事发现,运动锻炼通过加快骨骼肌细胞中犬尿氨酸代谢从而降低犬尿氨酸含量来降低抑郁[11]。

3 小结

3.1 目前研究中存在的问题

对于生活方式因素观察研究来说,很难完全排除膳食、吸烟或其他可能因素对结果的干扰;并不是所有队列研究分别评价了中等和大强度体力活动与癌症风险关系,许多队列研究缺乏计算MET-hous/周体力活动的具体数据;队列研究中自我报告的体力活动方法很难将体力活动的运动强度、持续时间和频率以及体力活动类型区分开,将可能导致一个非差异误差和对真正效果低估。

3.2 研究结论

基于上述综述,我们可以得出以下结论。首先,无论肥胖与否,体力活动增加与多种类型癌症风险降低相关,如乳腺癌、胃癌(含胃贲门癌)、结肠癌、子宫内膜癌、前列腺癌、肺癌和肝癌等。建议将体力活动增加作为降低癌症风险的一种有效干预措施。然后,体力活动降低癌症风险的最可能生化机制,包括直接和间接抗癌机制,直接机制包括:代谢类激素、表观遗传学影响、氧化应激、免疫力、慢性炎症、血管活性肠肽和鸢尾素等,间接机制包括:体重降低和雌激素、脂肪因子、维生素D和阳光暴露、心理上幸福感等。

4 建议研究方向

1.不同运动类型、强度和量的体力活动水平与多种类型癌症的相关性研究需要进一步进行。

2.需要进行大样本量的随机对照试验来归纳整理出降低各类型癌症风险的体力活动推荐值,将更好地用于制定政策,来鼓励大众通过增加体力活动降低各种癌症风险。

3.尽管致癌机制是清楚的,但是,运动抗癌机制需要进一步阐明,哪种强度和类型的体力活动能够更加有效降低癌症风险,需要进一步研究,不同年龄段肿瘤细胞对体力活动敏感性不一样的机制是什么,及其对应体力活动具体推荐值需要进一步研究。

[1] AMERICAN CANCER S. Global Cancer Facts & Global Cancer Facts & Figures. 3rd ed[M]. Atlanta,Georgia:American Cancer Society,2015.

[2] BOSTRÖM P,WU J,JEDRYCHOWSKI M,et al. Irisin induces brown fat of white adipose tissue in vivo and protects against diet-induced obesity and diabetes [J]. Nature,2012,481:463-468.

[3] CENTERS F D C A. Fastats:Exercise or Physical Activity[Z].2016.

[4] FERLAY J,SOERJOMATARAM I,ERVIK M,et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0,Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide:IARC cancer base. No. 11 [Internet].[J]. Int J Cancer J Int Du Cancer,2012,136(5):E359-E386.

[5] FERLAY J,SOERJOMATARAM I,ERVIK M,et al. Globocan 2012:estimated cancer incidence,mortality and prevalence worldwide 2012[J].2013.

[6] ORGANIZATION W H. Global health risks:mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks[J].2009:1-63.

[7] TARVER T. American cancer society cancer facts & figures 2014[J]. J Consumer Health Int,2012,16(3):366-367.

[8] THOMAS R,HOLM M. The benefits of exercise after cancer—an international review of the clinical and microbiological benefits[J].Br J Med Pract,2014,1:2-9.

[9] WISEMAN M. WCRF/AICR food,nutrition,physical activity,and the prevention of cancer:a global perspective. world cancer research fund/american institute for cancer research:Washington DC[J]. Proceed Nut Soc,2008,67(3):253-256.

[10] ABIOYE A I,ODESANYA M O,ABIOYE A I,et al. Physical activity and risk of gastric cancer:a meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. Br J Sports Med,2015,49(4):224-229.

[11] AGUDELO L Z,FEMENIA T,ORHAN F,et al. Skeletal muscle PGC-1alpha1 modulates kynurenine metabolism and mediates resilience to stress-induced depression[J]. Cell,2014,159(1):33-45.

[12] AREM H,MOORE S C,PATEL A,et al. Leisure time physical activity and mortality:a detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship[J]. JAMA Intern Med,2015,175(6):959-967.

[13] BEHRENS G,LEITZMANN M F. The association between physical activity and renal cancer:systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Br J Cancer,2013,108(4):798-811.

[14] BEHRENS G,MATTHEWS C E,MOORE S C,et al. The association between frequency of vigorous physical activity and hepatobiliary cancers in the NIH-AARP diet and health Study[J].Eur J Epidemiol,2013,28(1):55-66.

[15] BLAIR S N. Physical inactivity:the biggest public health problem of the 21st century[J]. Br J Sports Med,2009,43(1):1-2.

[16] BOOTH A,MAGNUSON A,FOUTS J,et al. Adipose tissue,obesity and adipokines:role in cancer promotion[J]. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig,2015,21(1):57-74.

[17] BORCH K B,WEIDERPASS E,BRAATEN T,et al. Physical activity and risk of endometrial cancer in the norwegian women and cancer (NOWAC) study[J]. Int J Cancer,2017,140(8):1809-1818.

[18] CALABRESE V,SCAPAGNINI G,COLOMBRITA C,et al.Redox regulation of heat shock protein expression in aging and neurodegenerative disorders associated with oxidative stress:a nutritional approach[J]. Amino Acids,2003,25(3-4):437-444.

[19] CAMPBELL K L,FOSTER-SCHUBERT K E,ALFANO C M,et al. Reduced-calorie dietary weight loss,exercise,and sex hormones in postmenopausal women:randomized controlled trial[J].J Clin Oncol,2012,30(19):2314-2326.

[20] CAMPBELL P T,GROSS M D,POTTER J D,et al. Effect of exercise on oxidative stress:a 12-month randomized,controlled trial[J]. Med Sci Sports Exe,2010,42(8):1448-1453.

[21] CHEN Y,YU C,LI Y. Physical activity and risks of esophageal and gastric cancers:a meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One,2014,9(2):e88082.

[22] CHOMISTEK A K,CHIUVE S E,JENSEN M K,et al. Vigorous physical activity,mediating biomarkers,and risk of myocardial infarction[J]. Med Sci Sports Exe,2011,43(10):1884-1890.

[23] CIOCCA D R,CALDERWOOD S K. Heat shock proteins in cancer:diagnostic,prognostic,predictive,and treatment implications[J]. Cell Stress Chaperones,2005,10(2):86-103.

[24] CROSS A J,HOLLENBECK A R,PARK Y. A large prospective study of risk factors for adenocarcinomas and malignant carcinoid tumors of the small intestine[J]. Cancer Causes Control,2013,24(9):1737-1746.

[25] de BOER M C,WORNER E A,VERLAAN D,et al. The mechanisms and effects of physical activity on breast cancer[J]. Clin Breast Cancer,2017.

[26] de SALLES B F,SIMAO R,FLECK S J,et al. Effects of resistance training on cytokines[J]. Int J Sports Med,2010,31(7):441-450.

[27] DIELI-CONWRIGHT C M,LEE K,KIWATA J L. Reducing the risk of breast cancer recurrence:an evaluation of the effects and mechanisms of diet and exercise[J]. Curr Breast Cancer Rep,2016,8(3):139-150.

[28] Du M,KRAFT P,ELIASSEN A H,et al. Physical activity and risk of endometrial adenocarcinoma in the nurses’ gealth study[J].Int J Cancer,2014,134(11):2707-2716.

[29] EMAUS A,VEIEROD M B,FURBERG A S,et al. Physical activity,heart rate,metabolic profile,and estradiol in premenopausal women[J]. Med Sci Sports Exe,2008,40(6):1022-1030.

[30] FLANAGAN J,GRAY P K,HAHN N,et al. Presence of the metabolic syndrome is associated with shorter time to castration-resistant prostate cancer[J]. Ann Oncol,2011,22(4):801-807.

[31] FOLKERD E,DOWSETT M. Sex hormones and breast cancer risk and prognosis[J]. Breast,2013,22 Suppl 2:S38-S43.

[32] FRIEDENREICH C M,CUST A E. Physical activity and breast cancer risk:impact of timing,type and dose of activity and population subgroup effects[J]. Br J Sports Med,2008,42(8):636-647.

[33] FRIEDENREICH C M,NEILSON H K,LYNCH B M. State of the epidemiological evidence on physical activity and cancer prevention[J]. Eur J Cancer,2010,46(14):2593-2604.

[34] FRIEDENREICH C M,NEILSON H K,WOOLCOTT C G,et al. Inflammatory marker changes in a yearlong randomized exercise intervention trial among postmenopausal women[J].Cancer Prev Res (Phila),2012,5(1):98-108.

[35] FRIEDENREICH C M,WOOLCOTT C G,MCTIERNAN A,et al. Alberta physical activity and breast cancer prevention trial:sex hormone changes in a year-long exercise intervention among postmenopausal women[J]. J Clin Oncol,2010,28(9):1458-1466.

[36] FRIEDENREICH C,CUST A,LAHMANN P H,et al. Physical activity and risk of endometrial cancer:the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition[J]. Int J Cancer,2007,121(2):347-355.

[37] GANNON N P,VAUGHAN R A,GARCIA-SMITH R,et al.Effects of the exercise-inducible myokine irisin on malignant and non-malignant breast epithelial cell behavior in vitro[J]. Int J Cancer,2015,136(4):E197-E202.

[38] GAY L J,FELDING-HABERMANN B. Contribution of platelets to tumour metastasis[J]. Nat Rev Cancer,2011,11(2):123-134.

[39] GLEESON M,BISHOP N C,STENSEL D J,et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise:mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease[J]. Nat Rev Immunol,2011,11(9):607-615.

[40] HALLAL P C,ANDERSEN L B,BULL F C,et al. Global physical activity levels:surveillance progress,pitfalls,and prospects[J].Lancet,2012,380(9838):247-257.

[41] HANKINSON A L,DAVIGLUS M L,BOUCHARD C,et al.Maintaining a high physical activity level over 20 years and weight gain[J]. JAMA,2010,304(23):2603-2610.

[42] HARRISS D J,ATKINSON G,BATTERHAM A,et al. Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk (2):a systematic review and meta-analysis of associations with leisure-time physical activity[J].Colorectal Dis,2009,11(7):689-701.

[43] HAYDON A M,MACINNIS R J,ENGLISH D R,et al. Effect of physical activity and body size on survival after diagnosis with colorectal cancer[J]. Gut,2006,55(1):62-67.

[44] HOLMAN D M,BERKOWITZ Z,GUY G J,et al. The association between demographic and behavioral characteristics and sunburn among U.S. adults - national health interview survey,2010[J]. Prev Med,2014,63:6-12.

[45] HOU W K,XU Y X,YU T,et al. Adipocytokines and breast cancer risk[J]. Chin Med J (Engl),2007,120(18):1592-1596.

[46] HOWARD R A,FREEDMAN D M,PARK Y,et al. Physical activity,sedentary behavior,and the risk of colon and rectal cancer in the NIH-AARP diet and health study[J]. Cancer Causes Control,2008,19(9):939-953.

[47] IRWIN M L,SMITH A W,MCTIERNAN A,et al. Influence of pre- and postdiagnosis physical activity on mortality in breast cancer survivors:the health,eating,activity,and lifestyle study[J].J Clin Oncol,2008,26(24):3958-3964.

[48] JARDE T,CALDEFIE-CHEZET F,GONCALVES-MENDES N,et al. Involvement of adiponectin and leptin in breast cancer:clinical and in vitro studies[J]. Endocr Relat Cancer,2009,16(4):1197-1210.

[49] JOCHEM C,LEITZMANN M F,KEIMLING M,et al. Physical activity in relation to risk of hematologic cancers:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev,2014,23(5):833-846.

[50] KAWANISHI N,MIZOKAMI T,YANO H,et al. Exercise attenuates M1 macrophages and CD8+ T cells in the adipose tissue of obese mice[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc,2013,45(9):1684-1693.

[51] KEIMLING M,BEHRENS G,SCHMID D,et al. The association between physical activity and bladder cancer:systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Br J Cancer,2014,110(7):1862-1870.

[52] KENFIELD S A,BATISTA J L,JAHN J L,et al. Development and application of a lifestyle score for prevention of lethal prostate cancer[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst,2016,108(3).

[53] KEY T,APPLEBY P,BARNES I,et al. Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women:reanalysis of nine prospective studies[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst,2002,94(8):606-616.

[54] KIM H J,LEE Y S,WON E H,et al. Expression of resistin in the prostate and its stimulatory effect on prostate cancer cell proliferation[J]. BJU Int,2011,108(2 Pt 2):E77-E83.

[55] KOSSMAN D A,WILLIAMS N I,DOMCHEK S M,et al. Exercise lowers estrogen and progesterone levels in premenopausal women at high risk of breast cancer[J]. J Appl Physiol (1985),2011,111(6):1687-1693.

[56] KROLIK M,MILNEROWICZ H. The effect of using estrogens in the light of scientific research[J]. Adv Clin Exp Med,2012,21(4):535-543.

[57] KRUK J,ABOUL-ENEIN H. What are the links of prostate cancer with physical activity and nutrition? :a systematic review article[J]. Iran J Public Health,2016,45(12):1558-1567.

[58] LEE I M,DJOUSSE L,SESSO H D,et al. Physical activity and weight gain prevention[J]. JAMA,2010,303(12):1173-1179.

[59] LEITZMANN M,POWERS H,ANDERSON A S,et al. European code against cancer 4th edition:Physical activity and cancer[J].Cancer Epidemiol,2015,39 Suppl 1:S46-S55.

[60] LIU Z,ZHANG L,SHI S,et al. Objectively assessed exercise behavior in chinese patients with early-stage cancer:a predictorof perceived benefits,communication with doctors,medical coping modes,depression and quality of life[J]. PLoS One,2017,12(1):e169375.

[61] LOPE V,MARTIN M,CASTELLO A,et al. Physical activity and breast cancer risk by pathological subtype[J]. Gynecol Oncol,2017,144(3):577-585.

[62] LUBIK A A,GUNTER J H,HOLLIER B G,et al. IGF2 increases de novo steroidogenesis in prostate cancer cells[J]. Endocr Relat Cancer,2013,20(2):173-186.

[63] LUSCOMBE C J,FRENCH M E,LIU S,et al. Prostate cancer risk:associations with ultraviolet radiation,tyrosinase and melanocortin-1 receptor genotypes[J]. Br J Cancer,2001,85(10):1504-1509.

[64] MAGBANUA M J,RICHMAN E L,SOSA E V,et al. Physical activity and prostate gene expression in men with low-risk prostate cancer[J]. Cancer Causes Control,2014,25(4):515-523.

[65] MARKOZANNES G,TZOULAKI I,KARLI D,et al. Diet,body size,physical activity and risk of prostate cancer:an umbrella review of the evidence[J]. Eur J Cancer,2016,69:61-69.

[66] MARTINEZ M E,HEDDENS D,EARNEST D L,et al. Physical activity,body mass index,and prostaglandin E2 levels in rectal mucosa[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst,1999,91(11):950-953.

[67] MCCULLOUGH L E,MCCLAIN K M,GAMMON M D. The promise of leisure-time physical activity to reduce risk of cancer development[J]. JAMA Intern Med,2016,176(6):826-827.

[68] MCMICHAEL A J. Food,nutrition,physical activity and cancer prevention. authoritative report from world cancer research fund provides global update[J]. Public Health Nutr,2008,11(7):762-763.

[69] MONDUL A M,WEINSTEIN S J,MOY K A,et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and prostate cancer survival[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev,2016,25(4):665-669.

[70] MOORE S C,LEE I M,WEIDERPASS E,et al. Association of leisure-time physical activity with risk of 26 types of cancer in 1.44 million adults[J]. JAMA Intern Med,2016,176(6):816-825.

[71] MOORE S C,PETERS T M,AHN J,et al. Physical activity in relation to total,advanced,and fatal prostate cancer[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev,2008,17(9):2458-2466.

[72] NAHLEH Z,TFAYLI A,NAJM A,et al. Heat shock proteins in cancer:targeting the ‘chaperones’[J]. Future Med Chem,2012,4(7):927-935.

[73] NIU J,JIANG L,GUO W,et al. The association between leptin level and breast cancer:a meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One,2013,8(6):e67349.

[74] NTANASIS-STATHOPOULOS J,TZANNINIS J G,PHILIPPOU A,et al. Epigenetic regulation on gene expression induced by physical exercise[J]. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact,2013,13(2):133-146.

[75] ORNISH D,LIN J,CHAN J M,et al. Effect of comprehensive lifestyle changes on telomerase activity and telomere length in men with biopsy-proven low-risk prostate cancer:5-year follow-up of a descriptive pilot study[J]. Lancet Oncol,2013,14(11):1112-1120.

[76] ORNISH D,MAGBANUA M J,WEIDNER G,et al. Changes in prostate gene expression in men undergoing an intensive nutrition and lifestyle intervention[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,2008,105(24):8369-8374.

[77] PARKIN D M. 9. Cancers attributable to inadequate physical exercise in the UK in 2010[J]. Br J Cancer,2011,105 Suppl 2:S38-S41.

[78] PIJPE A,MANDERS P,BROHET R M,et al. Physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers[J].Breast Cancer Res Treat,2010,120(1):235-244.

[79] PILZ S,KIENREICH K,TOMASCHITZ A,et al. Vitamin D and cancer mortality:systematic review of prospective epidemiological studies[J]. Anticancer Agents Med Chem,2013,13(1):107-117.

[80] PISCHKE C R,FRENDA S,ORNISH D,et al. Lifestyle changes are related to reductions in depression in persons with elevated coronary risk factors[J]. Psychol Health,2010,25(9):1077-1100.

[81] PIZOT C,BONIOL M,MULLIE P,et al. Physical activity,hormone replacement therapy and breast cancer risk:a meta-analysis of prospective studies[J]. Eur J Cancer,2016,52:138-154.

[82] PLATZ E A,TILL C,GOODMAN P J,et al. Men with low serum cholesterol have a lower risk of high-grade prostate cancer in the placebo arm of the prostate cancer prevention trial[J].Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev,2009,18(11):2807-2813.

[83] PRASAD S M,EGGENER S E,LIPSITZ S R,et al. Effect of depression on diagnosis,treatment,and mortality of men with clinically localized prostate cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol,2014,32(23):2471-2478.

[84] PROVATOPOULOU X,GEORGIOU G P,KALOGERA E,et al. Serum irisin levels are lower in patients with breast cancer:association with disease diagnosis and tumor characteristics[J].BMC Cancer,2015,15:898.

[85] PSALTOPOULOU T,NTANASIS-STATHOPOULOS I,TZANNINIS I G,et al. Physical activity and gastric cancer risk:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Clin J Sport Med,2016,26(6):445-464.

[86] RADOM-AIZIK S,ZALDIVAR F,HADDAD F,et al. Impact of brief exercise on peripheral blood NK cell gene and microRNA expression in young adults[J]. J Appl Physiol (1985),2013,114(5):628-636.

[87] REID-ARNDT S A,COX C R. Stress,coping and cognitive deficits in women after surgery for breast cancer[J]. J Clin Psychol Med Settings,2012,19(2):127-137.

[88] RENEHAN A G,TYSON M,EGGER M,et al. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer:a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies[J]. Lancet,2008,371(9612):569-578.

[89] RESTITUTO P,COLINA I,VARO J J,et al. Adiponectin diminishes platelet aggregation and sCD40L release. potential role in the metabolic syndrome[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab,2010,298(5):E1072-E1077.

[90] RUNDQVIST H,AUGSTEN M,STROMBERG A,et al. Effect of acute exercise on prostate cancer cell growth[J]. PLoS One,2013,8(7):e67579.

[91] RYAN C J,HAQQ C M,SIMKO J,et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in local and metastatic prostate cancer[J]. Urol Oncol,2007,25(2):134-140.

[92] SCHMID D,BEHRENS G,MATTHEWS C E,et al. Physical activity and risk of colon cancer in diabetic and nondiabetic US adults[J]. Mayo Clin Proc,2016,91(12):1693-1705.

[93] SCHMIDT S,MONK J M,ROBINSON L E,et al. The integrative role of leptin,oestrogen and the insulin family in obesity-associated breast cancer:potential effects of exercise[J]. Obes Rev,2015,16(6):473-487.

[94] SCHMITZ K H,WILLIAMS N I,KONTOS D,et al. Dose-response effects of aerobic exercise on estrogen among women at high risk for breast cancer:a randomized controlled trial[J].Breast Cancer Res Treat,2015,154(2):309-318.

[95] SCOTT J M,KHAKOO A,MACKEY J R,et al. Modulation of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity by aerobic exercise in breast cancer:current evidence and underlying mechanisms[J]. Circulation,2011,124(5):642-650.

[96] SHARAFI H,RAHIMI R. The effect of resistance exercise on p53,caspase-9,and caspase-3 in trained and untrained men[J]. J Strength Cond Res,2012,26(4):1142-1148.

[97] SHEPHARD R J. Physical activity and prostate cancer:an updated review[J]. Sports Med,2017 ,47 (6) :1055.

[98] SHORS A R,SOLOMON C,MCTIERNAN A,et al. Melanoma risk in relation to height,weight,and exercise (United States)[J].Cancer Causes Control,2001,12(7):599-606.

[99] SIMONS C C,HUGHES L A,van ENGELAND M,et al. Physical activity,occupational sitting time,and colorectal cancer risk in the netherlands cohort study[J]. Am J Epidemiol,2013,177(6):514-530.

[100] SINGH S,EDAKKANAMBETH V J,DEVANNA S,et al.Physical activity is associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Cancer Prev Res (Phila),2014,7(1):12-22.

[101] SOTGIA F,MARTINEZ-OUTSCHOORN U E,LISANTI M P. Mitochondrial oxidative stress drives tumor progression and metastasis:should we use antioxidants as a key component of cancer treatment and prevention?[J]. BMC Med,2011,9:62.

[102] STARK J R,LI H,KRAFT P,et al. Circulating prediagnostic interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein and prostate cancer incidence and mortality[J]. Int J Cancer,2009,124(11):2683-2689.

[103] THOMAS R J,KENFIELD S A,JIMENEZ A. Exercise-induced biochemical changes and their potential influence on cancer:a scientific review[J]. Br J Sports Med,2017,51(8):640-644.

[104] TRAUSTADOTTIR T,DAVIES S S,SU Y,et al. Oxidative stress in older adults:effects of physical fitness[J]. Age (Dordr),2012,34(4):969-982.

[105] VALDEHITA A,BAJO A M,FERNANDEZ-MARTINEZ A B,et al. Nuclear localization of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)receptors in human breast cancer[J]. Peptides,2010,31(11):2035-2045.

[106] VELJKOVIC M,BRANCH D R,DOPSAJ V,et al. Can natural antibodies to VIP or VIP-like HIV-1 glycoprotein facilitate prevention and supportive treatment of breast cancer?[J]. Med Hypotheses,2011,77(3):404-408.

[107] WANG J S,WENG T P. Hypoxic exercise training promotes antitumour cytotoxicity of natural killer cells in young men[J].Clin Sci (Lond),2011,121(8):343-353.

[108] WISEMAN M. The second world cancer research fund/american institute for cancer research expert report. food,nutrition,physical activity,and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective[J]. Proc Nutr Soc,2008,67(3):253-256.

[109] WOLIN K Y,YAN Y,COLDITZ G A,et al. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention:a meta-analysis[J]. Br J Cancer,2009,100(4):611-616.

[110] WOLPIN B M,BAO Y,QIAN Z R,et al. Hyperglycemia,insulin resistance,impaired pancreatic beta-cell function,and risk of pancreatic cancer[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst,2013,105(14):1027-1035.

[111] WU Y,ZHANG D,KANG S. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer:a meta-analysis of prospective studies[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat,2013,137(3):869-882.

[112] XIE Y,WOLFF D W,LIN M F,et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide transactivates the androgen receptor through a protein kinase a-dependent extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in prostate cancer LNCaP cells[J]. Mol Pharmacol,2007,72(1):73-85.

[113] ZGAGA L,THEODORATOU E,FARRINGTON S M,et al.Plasma vitamin D concentration influences survival outcome after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol,2014,32(23):2430-2439.

[114] ZIMMER P,JAGER E,BLOCH W,et al. Influence of a six month endurance exercise program on the immune function of prostate cancer patients undergoing antiandrogen- or chemotherapy:design and rationale of the proImmun study[J]. BMC Cancer,2013,13:272.

Research Progress of the Relationship between Physical Activity and Risk of Many Types of Cancer and Its Possible Mechanism

Cancer has become the second leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the world. The evidence suggests that 9% to 19% of the cancer incidence in Europe is due to lack of physical activity. In order to decrease the risk of cancer,lifestyle intervention,increasing the physical activity,may become a cost-effective and long-term cancer control option. The aim of this study was to systematic review the association of physical activity/exercise and the risk of cancer,and the potential biological mechanism of physical activity/exercise on carcinogenesis,which will provide theoretical support to promote and advocate physical activity as a key component of cancer prevention and the promotion of healthy lifestyles. Methods:In this paper,we searched the keywords “physical activity”,“leisure activity” ,”exercise”,“exercise”,“cancer”,“risk”,“mechanism” and “biological changes” in the databases of PubMed and Highwire. A total of 23 articles were included,which were published in 2012-2017. Results:1) Whether or not obesity,the increase of physical activity was with associated with reduced risk of many types of cancer. 2) The most likely biochemical mechanisms of physical activity to reduce cancer risk include direct anticancer pathway and indirect anticancer pathway.Direct anti-cancer mechanisms include metabolic hormones,epigenetic effects,oxidative stress,immunity,chronic inflammation and so on. Indirect anti-cancer mechanisms include:weight loss and estrogen,adipokines,vitamin D and sunlight exposure,elevated mood and so on. Conclusion:1) It is recommended that physical activity be added as an effective intervention to prevent cancer risk. 2)The physical activity reduces the risk of many types of cancer through a direct anticancer pathway and indirect anticancer pathway.

physical activity;cancer;association;risk

G804.49

A

1000-677X(2017)09-0074-13

10. 16469/j. css. 201709008

2017-06-29;

2017-09-09

孙景权 ,男,讲师,博士,研究方向为运动与体质健康,E-mail:sjqdiligent@163.com。

1. 四川大学 体育学院,四川 成都 610065;2. 成都大学体育学院,四川 成都 610106;3. 沈阳工业大学 体育部,辽宁 沈阳 110870;4.国家体育总局运动医学研究所,北京 100061

1. Sichuan University,Chengdu 610065,China;2.Chengdu University,Chengdu 610106,China;3.Shenyang University of Technology,Shenyang,110870,China;4.China Institute of Sports Medicine,Beijing 100061,China.274 965名非糖尿病人群(年龄50~71岁)13年发现,在13年跟踪中,480名糖尿病人和4 151名非糖尿病人出现结肠癌;在控制年龄和性别变量后,相比从来不/很少进行体力活动糖尿病人群,每周进行≥7h体力活动的糖尿病人群患结肠癌风险降低;对于非糖尿病人群来说,体力活动与结肠癌风险呈现负相关。他们认为,对于非糖尿病人群,体力活动显著降低结肠癌风险,且不受其他变量影响;更大样本量的研究需要进一步探讨,体力活动是否对糖尿病人群结肠癌风险存在健康受益[92]。那么,降低结肠癌风险的有效强度是什么?Howard等调查了不同强度体力活动和结肠癌风险之间关系,发现,中等到大强度体力活动与男性结肠癌风险之间存在统计学意义上的显著负相关;然而,这种关系在女性中不明显[46]。男女性别出现不同结果原因可能是,女性将她们一半活动时间花费在家务上面[99],然而,相对规律性体力活动,家庭体力活动很难通过自我报告问卷方式精确计算。总之,大部分研究表明,对于大众人群来说,相对于低体力活动水平,高体力活动水平能够使结肠癌风险降低14%~24%[42,109]。因此,建议健康人群和代谢性疾病人群(如糖尿病人群)通过进行运动锻炼或增加体力活动来达到降低结肠癌风险的目的。