Indocyanine green fl uoroscopy and liver transplantation: a new technique for the intraoperative assessment of bile duct vascularization

2017-08-16LaurentCoubeau,JulieFrezin,RomainDehon等

Indocyanine green fl uoroscopy and liver transplantation: a new technique for the intraoperative assessment of bile duct vascularization

To the Editor:

Biliary tract complications remain the Achilles’ heel of liver transplantation (LT)[1]and the transplant community is exploring ways of tackling this problem. A wellvascularized bile duct is a prerequisite for successful bile duct reconstruction. Vascular assessment is usually performed by evaluating the macroscopic aspects of both recipient and donor bile duct stumps. We present an original technique for intraoperative evaluation of the blood supply of the donor bile duct using indocyanine green (ICG) fl uorescence.

The liver graft was from a 39-year-old donation after circulatory death (DCD). The graft was mildly steatotic and arterial vascularization consisted of an accessory left hepatic artery originating from the left gastric artery. The graft was procured using Institut-Georges-Lopez-1 (IGL-1®) solution (Institut Georges Lopez, SAS, Lissieu, France). The surgical team performed inferior vena cavasparing hepatectomy and the graft was implanted using a latero-lateral cavo-caval anastomosis. Cold and warm ischemia times were 681 and 45 minutes, respectively. Rapid and homogenous allograft reperfusion was followed by rapid bile production.

Intraoperative fl uoroscopy was performed after injecting 0.25 mg/kg of ICG (Akorn, Lake Forrest, IL, USA) via a central catheter. A Pinpoint Endoscopic Fluorescence Imaging® (Novadaq Corp., Bonita Springs, FL, USA) device was used for detecting the fl uorescent signal. Fluorescence was seen in the vascularized liver graft 28 seconds after intravenous injection of ICG and in the biliary stump at about 45 seconds after injection. The stumps of both donor and recipient bile ducts were assessed by real-time perfusion.

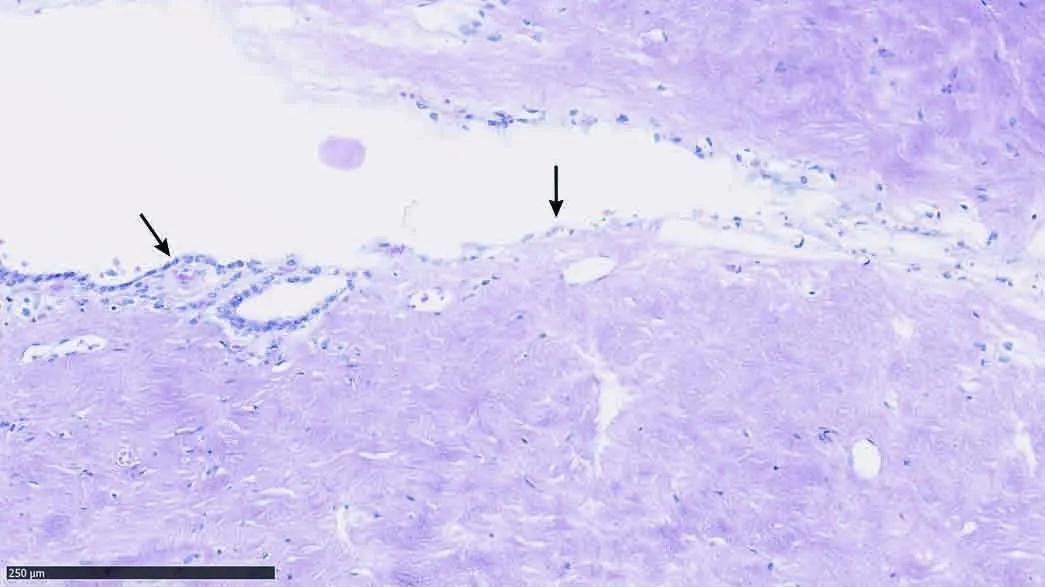

Even though macroscopic evaluation of the donor biliary stump suggested suboptimal vascularization of the distal stump, our technique def i nitively highlighted the ischemic area for resection (Figs. 1 and 2). Following ICG assessment, the ischemic area was resected and an end-to-end duct-to-duct anastomosis without a T-tube was performed using 7.0 absorbable interrupted sutures (PDS® Ethicon, Johnson and Johnson, Somerville, Ohio, USA). The resected common bile duct was collected for hematoxylin and eosin staining, which involved fi xing in 10% formalin, embedding in paraff i n, and sectioning at 5-μm intervals. We found bile duct epithelial cell loss and separation of the epithelium from the subepithelial connective tissue, both of which are typical signs of ischemia (Fig. 3). Routine percutaneous cholangiography did not show stricture or leakage 6 months after surgery and there were no unusual fi ndings after 10 months of follow-up.

Objective assessment of the vascular system at the site of any surgical anastomosis is a crucial process in ensuring wound healing and in the prevention of anastomotic leaks or strictures. This principle applies to any procedure involving the connection of two structures, such as ureteral anastomosis, and biliary and digestive anastomoses.[2]Traditionally, tissue viability and blood supply are evaluated by assessing macroscopic aspects and through back-bleeding of the stumps. The literaturecontains numerous examples of the discrepancy between“subjective” macroscopic assessment by the surgeon and“objective” assessment using ICG fl uorescence imaging.[2]

Fig. 1. Macroscopic evaluation of donor (A) and recipient (B) biliary stumps during liver transplantation.

Fig. 2. Objective evaluation of biliary stump vascularization using indocyanine green fluorescence imaging. The ischemic portion on the donor bile duct stump (A, C) is clearly identif i ed, and contrasts with the good blood supply in the recipient bile duct (B, D).

Fig. 3. Pathological fi ndings from the resected biliary stump, demonstrating epithelial cell loss and separation of the epithelium from the subepithelial connective tissue (right arrow), and normal epithelium (left arrow).

ICG is routinely used by many Asian hepatobiliary surgeons to evaluate preoperative liver function, to detect the intraoperative liver tumors and to analyze biliary tract anatomy during both standard hepatobiliary surgery and living donor LT. Kokudo and Ishizawa[3]introduced the fl uorescence imaging for LT. This methodology has extended the armamentarium of the modern hepatobiliary and transplant surgeon beyond standard visual inspection and intraoperative ultrasonography. Indeed, fl uorescence imaging has been used as a variant of intraoperative cholangiography,[4]as a tool to perform anatomical liver resections,[5]and to assess the blood supply of liver grafts during transplantation complicated by early portal vein thrombosis.[6]

ICG shows a high hepatic extraction rate (usually above 70%), which means that its rate of clearance approaches the rate of hepatic blood fl ow. After injection, ICG remains to be conf i ned to the vascular compartment due to its high level of binding to plasma proteins. Blood half-life is 2-3 minutes and it is eliminated almost exclusively by the liver into the bile with the original molecule. The elimination phase lasts for 10-20 minutes and is prolonged in cases of liver dysfunction or reduced hepatic blood fl ow.[7]Consequently, the timing of image procurement following intravenous injection of ICG must be tailored to the individual situation.[8]In all cases, however, imaging procurement for tissue vascularization should be performed quickly after ICG injection (within 30 seconds).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the fi rst reported instance of ICG fl uorescence imaging to assess the vascularization of bile ducts during LT. Up to 25% of LT recipients experience biliary tract complications.[1,9,10]Despite improved procurement and implantation techniques and organ preservation methods, biliary tract complication remains a major cause of morbidity resulting in repeated endoscopic and percutaneous biliary interventions and, in some cases, re-transplantation. This problem has become more relevant during the last decade due to the more frequent use of DCD donors. In this type of LT, patients frequently develop non-anastomotic or anastomotic strictures.[11]Optimizing evaluation of the vascular supply of the donor bile duct stump by ICG fl uorescence imaging could be of particular importance in this context as a means to reduce the incidence of anastomotic complications.

“希望来吧”让孩子们在父母奔波的时候也能有陪伴的温暖,让孩子们在寂寞的时候也能享受课堂带来的乐趣。下一步,“希望来吧”将试点实施政府采购,吸引优质社会组织参与运营,让关爱的雨露流入孩子心田,让关爱的力量从这里传递!□

In conclusion, ICG fl uorescence imaging identif i ed donor bile duct ischemia not identif i ed by macroscopic evaluation, suggesting it is a useful tool in LT. This tool could be particularly useful in the setting of DCD LT, which is associated with a high incidence of biliary tract complication. A controlled trial to prove the superiority of ICG fl uorescence imaging over macroscopic evaluation of the vascular supply of the biliary tract during LT is warranted.

Laurent Coubeau, Julie Frezin, Romain Dehon, Jan LerutLerut and Raymond Reding

Starzl Unit Abdominal Transplantation, Department of Abdominal and Transplantation Surgery (Coubeau L, Frezin J, Lerut J and Reding R) and Pathology Unit (Dehon R), Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc, Université catholique Louvain (UCL), Brussels, Belgium

Contributors: CL proposed the study, performed the research and wrote the fi rst draft. FJ collected and analyzed the data and reviewed the draft. LJ and RR revised the manuscript. DR did the pathological analysis. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. CL is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Competing interest: No benef i ts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Lerut J, Gordon RD, Iwatsuki S, Esquivel CO, Todo S, Tzakis A, et al. Biliary tract complications in human orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation 1987;43:47-51.

2 Kawada K, Hasegawa S, Wada T, Takahashi R, Hisamori S, Hida K, et al. Evaluation of intestinal perfusion by ICG fl uorescence imaging in laparoscopic colorectal surgery with DST anastomosis. Surg Endosc 2017;31:1061-1069.

3 Kokudo N, Ishizawa T, eds. Fluorescent imaging: treatment ofhepatobiliary and pancreatic diseases (Frontiers of Gastrointestinal Research, Vol. 31). Basel: Karger; 2013.

4 Ishizawa T, Tamura S, Masuda K, Aoki T, Hasegawa K, Imamura H, et al. Intraoperative fl uorescent cholangiography using indocyanine green: a biliary road map for safe surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:e1-4.

5 Inoue Y, Arita J, Sakamoto T, Ono Y, Takahashi M, Takahashi Y, et al. Anatomical liver resections guided by 3-dimensional parenchymal staining using fusion indocyanine green fl uorescence imaging. Ann Surg 2015;262:105-111.

6 Kawaguchi Y, Akamatsu N, Ishizawa T, Kaneko J, Arita J, Sakamoto Y, et al. Evaluation of hepatic perfusion in the liver graft using fl uorescence imaging with indocyanine green. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;14:149-151.

7 De Gasperi A, Mazza E, Prosperi M. Indocyanine green kinetics to assess liver function: ready for a clinical dynamic assessment in major liver surgery? World J Hepatol 2016;8:355-367.

8 Alander JT, Kaartinen I, Laakso A, Pätilä T, Spillmann T, Tuchin VV, et al. A review of indocyanine green fl uorescent imaging in surgery. Int J Biomed Imaging 2012;2012:940585.

9 Balderramo D, Navasa M, Cardenas A. Current management of biliary complications after liver transplantation: emphasis on endoscopic therapy. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;34:107-115.

10 Verdonk RC, Buis CI, Porte RJ, van der Jagt EJ, Limburg AJ, van den Berg AP, et al. Anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation: causes and consequences. Liver Transpl 2006;12:726-735.

11 Foley DP, Fernandez LA, Leverson G, Chin LT, Krieger N, Cooper JT, et al. Donation after cardiac death: the University of Wisconsin experience with liver transplantation. Ann Surg 2005;242:724-731.

Published online July 13, 2017.

Without libraries what have we? We have no past and no future.

—Kay Bradbury

Julie Frezin

(Email: julie.frezin@uclouvain.be)

10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60040-7)

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Effects of multimodal fast-track surgery on liver transplantation outcomes

- Characteristics of recipients with complete immunosuppressant withdrawal after adult liver transplantation

- Predictive value of C-reactive protein/albumin ratio in acute pancreatitis

- Bilioenteric anastomotic stricture in patients with benign and malignant tumors: prevalence, risk factors and treatment

- Interaction between insulin-like growth factor binding protein-related protein 1 and transforming growth factor beta 1 in primary hepatic stellate cells

- Hepatopancreatoduodenectomy for advanced hepatobiliary malignancies: a single-center experience