Bilioenteric anastomotic stricture in patients with benign and malignant tumors: prevalence, risk factors and treatment

2017-08-16JiQiaoZhuXianLiangLiJianTaoKouHongMengDongHuanYeLiuChunBaiJunMaandQiangHe

Ji-Qiao Zhu, Xian-Liang Li, Jian-Tao Kou, Hong-Meng Dong, Huan-Ye Liu, Chun Bai, Jun Ma and Qiang He

Beijing, China

Bilioenteric anastomotic stricture in patients with benign and malignant tumors: prevalence, risk factors and treatment

Ji-Qiao Zhu, Xian-Liang Li, Jian-Tao Kou, Hong-Meng Dong, Huan-Ye Liu, Chun Bai, Jun Ma and Qiang He

Beijing, China

BACKGROUND:Stricture formation at the bilioenteric anastomosis is a rare but important postoperative complication. However, information on this complication is lacking in the literature. In the present study, we aimed to assess its prevalence and predictive factors, and report our experience in managing bilioenteric anastomotic strictures over a ten-year period.

METHODS:A total of 420 patients who had undergone bilioenteric anastomosis due to benign or malignant tumors between February 2001 and December 2011 were retrospectively reviewed. Univariate and multivariate modalities were used to identify predictive factors for anastomotic stricture occurrence. Furthermore, the treatment of anastomotic stricture was analyzed.

RESULTS:Twenty-one patients (5.0%) were diagnosed with bilioenteric anastomotic stricture. There were 12 males and 9 females with a mean age of 61.6 years. The median time after operation to anastomotic stricture was 13.6 months (range, 1 month to 5 years). Multivariate analysis identif i ed that surgeon volume (≤30 cases) (odds ratio: -1.860;P=0.044) was associated with the anastomotic stricture while bile duct size (>6 mm) (odds ratio: 2.871;P=0.0002) had a negative association. Balloon dilation was performed in 18 patients, biliary stenting in 6 patients, and reoperation in 4 patients. Five patients died of tumor recurrence, and one of heart disease.

CONCLUSIONS:Bilioenteric anastomotic stricture is an uncommon complication that can be treated primarily by interventional procedures. Bilioenteric anastomosis may be performed by a surgeon in his earlier training period under the guidance of an experienced surgeon. Bile duct size >6 mm may play a protective role.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2017;16:412-417)

anastomotic stricture; bilioenteric anastomosis; bile duct size; surgeon volume

Introduction

Bilioenteric anastomosis is a classic surgical procedure performed to reestablish biliary continuity in the setting of various diseases. However, anastomotic stricture sometimes develops and, if unrecognized or managed improperly, can cause serious complications, such as biliary cirrhosis, portal hypertension, hepatic failure and recurrent cholangitis.[1,2]Most cases of anastomotic stricture reported in the literature have occurred after liver transplantation or bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholesystectomy.[3-5]In contrast, there are only sparse reports on anastomotic stricture development after surgical treatment of benign and malignant tumors.[6-12]There are two reasons that account for these phenomena: a low incidence rate of anastomotic stricture, ranging from 2%-11.9%, and its late development after discharge (from 12 days to 106 months).[6-11]Risk factors for anastomotic stricture have been discussed in some articles;[6,7,10,11,13]of these, however, one researched anastomotic stricture occurring within only 90 postoperative days, and another studied anastomotic stricture only in patients with benign disorders. Therefore, therisk factors for anastomotic stricture are still under debate.

In this study, we aimed to determine the incidence of anastomotic stricture, to establish the predictors of its occurrence, and to report our experience treating this complication.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively collected the data of 420 patients who underwent bilioenteric anastomosis due to benign and malignant tumors between February 2001 and December 2011 at the Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreaticosplenic Surgery of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital. The patients had follow-up three months after operation and at regular intervals thereafter. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital in accordance with the 1964Declaration of Helsinkiand its later amendments. For this type of study, formal consent from the patients was waived.

Def i nitions

There is no standard def i nition of anastomotic stricture. Based on previous articles,[6,7,10,11,13]anastomotic stricture should be def i ned as a symptomatic patient with liver dysfunction, treatment with balloon dilatation, stenting or surgical reconstruction improves symptom and liver function. Our experiences indicated that preoperative biliary drainage, especially percutaneous biliary drainage, was preferred compared with a stent when the total bilirubin reached 300 μmol/L or more, or if other procedures could not be performed within two weeks. The stent was usually removed six weeks postoperatively for decompression. Surgeons were divided into two groups according to the cases of bilioenteric anastomosis performed (≤30 cases and >30 cases). Biliary bypass was performed for benign bile duct tumors and unresectable malignant tumors, pancreaticoduodenectomy for the rest benign tumors, and radical resection for resectable maglignant tumors.

Postoperative pancreatic fi stula (POPF) was diagnosed when the amylase concentration in the drainage fl uid was greater than 3 times the upper normal serum value on or after postoperative day 3.[14]

Surgical technique

Bilioenteric anastomosis performed in these patients included Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy and hepaticojejunostomy. The gallbladder was removed, and the bile duct was transected and left untied. A piece of gauze was placed around the bile duct stump to protect the surgical site from pollution by bile. In patients with a nondilated bile duct, we created a sloped end or cut a slit in the anterior wall for the anastomosis. During bilioenteric anastomosis, a corresponding opening in the jejunum was cut via electrocautery. A single layer of the end-toside mucosa-to-mucosa anastomosis was initiated from the posterior wall. A double-armed 6-0 polydioxanone (PDS) suture was applied in a continuous fashion from the 9 to the 3 o’clock positions on the biliary side in the counterclockwise direction, and from the corresponding 3 to 9 o’clock positions on the jejunal side in the clockwise direction. When posterior wall suturing was completed, the suture of the back wall was then tightened and tied. Another double-armed 6-0 PDS suture was used for the anterior wall in a continuous or interrupted fashion according to surgeon preference. Upon completion of the anterior wall, the sutures were tied. The placement of either a stent or T-tube was decided upon by the surgeons. A drain was positioned near the bilioenteric anastomosis. The jejunal loop of approximately 40 cm was kept far from the anastomosis.

Treatment

Anastomotic stricture was assessed by interventional radiology with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography in patients with repeated abdominal pain, fever, jaundice and hepatic damage. These patients were managed initially with balloon dilatation or stenting, and fi nally, by reoperation if the other measures failed.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were carried out by using SPSS 19.0 computer software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables and the independent samplesttest was employed for quantitative variables. Variables on univariate analysis withPvalues less than 0.05 were subjected to further analysis to identify independent predictive factors for anastomotic stricture. Relative risk was expressed as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% conf i dence interval (CI). Statistical signif i cance was set atP<0.05. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for making the survival curve.

Results

Biliary stricture at the bilioenteric anastomosis

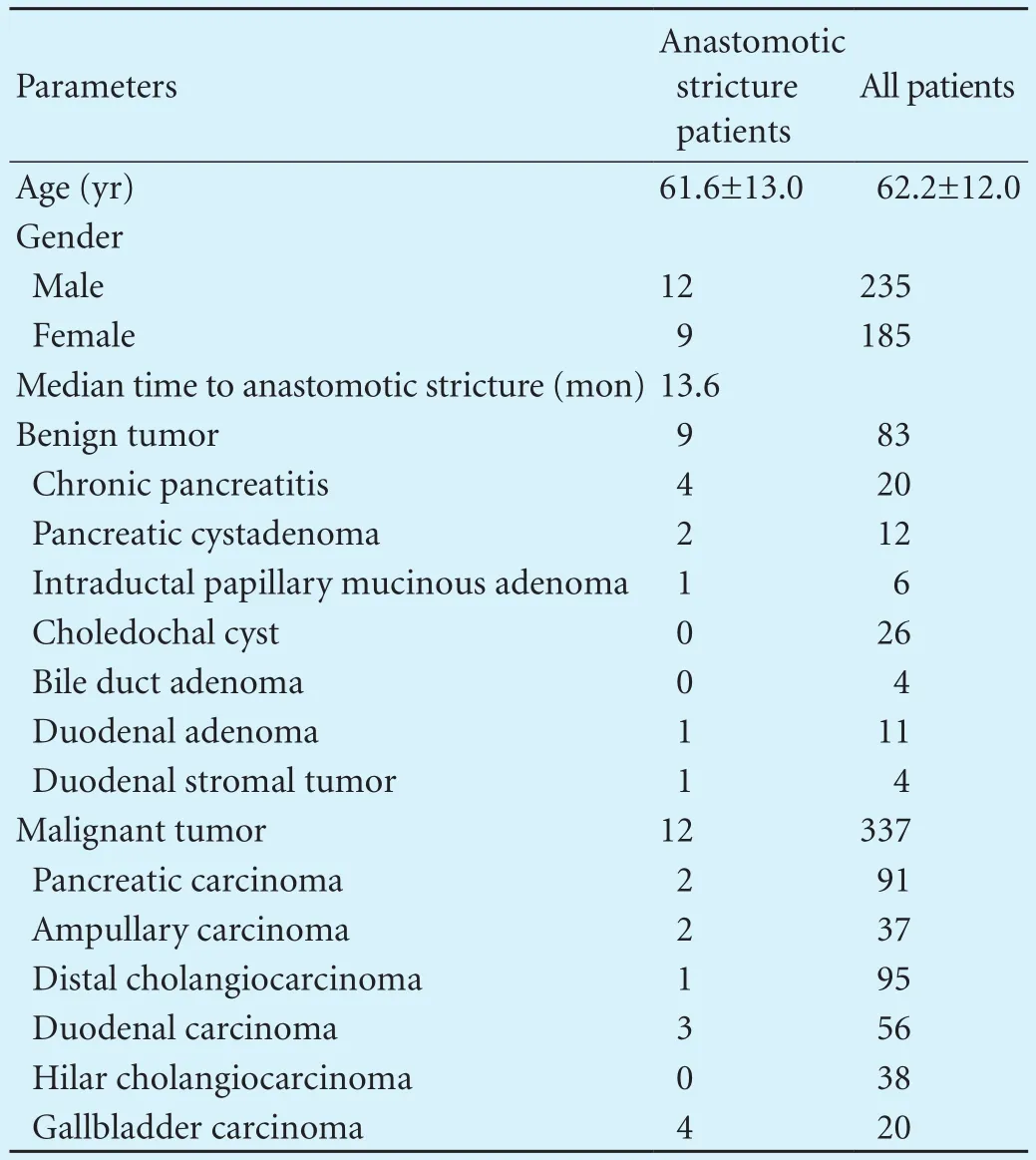

Data from patients who underwent bilioenteric anastomosis were collected; the procedure for benign cases were 83 (19.8%) and malignant 337 (80.2%). Twenty-one (21/420, 5.0%) patients (12 males and 9 females) with a mean age of 61.6 years were subsequently diagnosed asanastomotic stricture. The median time to anastomotic stricture following operation was 13.6 months (range, 1 month to 5 years). Nine (42.9%) of the anastomotic stricture patients had originally been treated for benign tumors (Table 1). No hepatic arterial reconstruction was performed.

Risk factors of anastomotic stricture

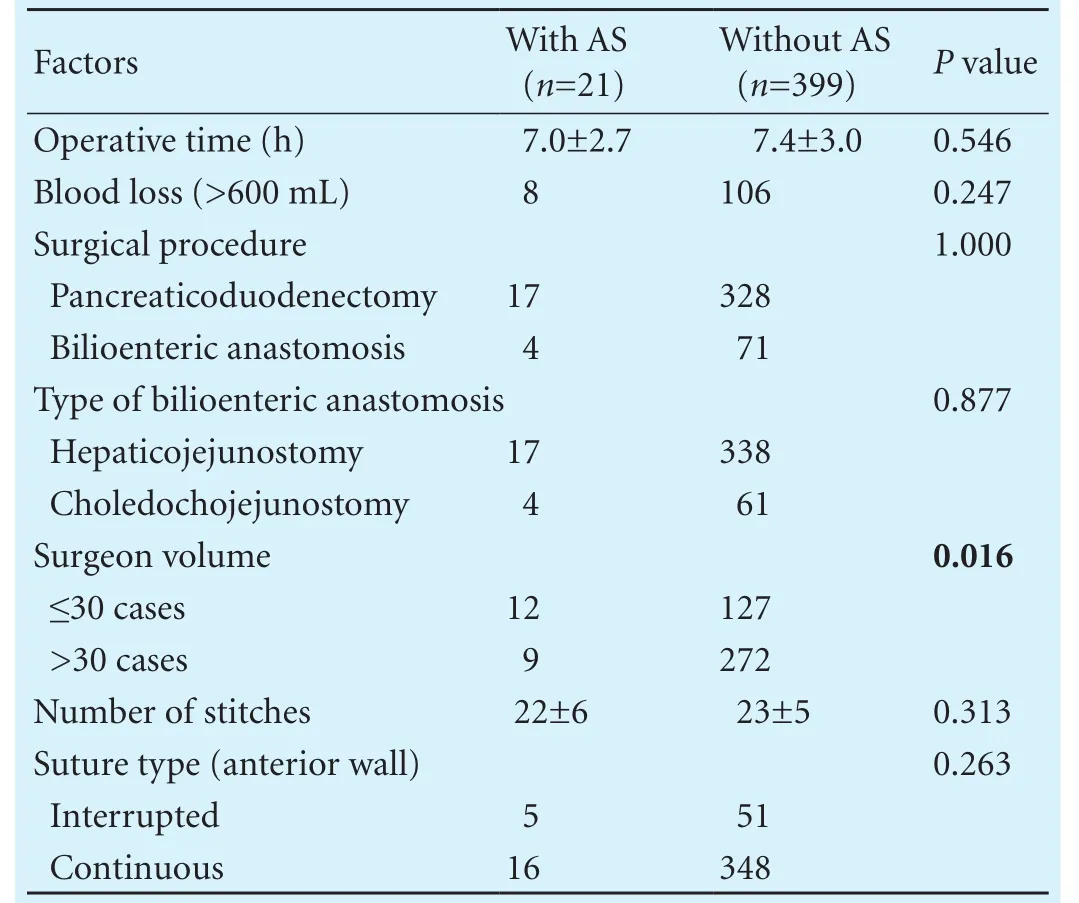

Possible risk factors were categorized into three types: preoperative, operative and postoperative risk factors. Possible preoperative risk factors are summarized in Table 2. We analyzed age, gender, benign tumor, albumin (>35 g/L), elevated transaminases, preoperative jaundice, bile duct size (>6 mm), preoperative biliary drainage or stenting, elevated CA19-9, preoperative chemoradiation, diabetes mellitus, smoking, heart diseases and body mass index (>25 kg/m2). Benign tumor and bile duct size (>6 mm) were signif i cantly different between patients with anastomotic stricture and those without anastomotic stricture (P=0.014 andP=0.008, respectively). When the possible operative risk factors were analyzed, surgeon volume (≤30 cases) was found to be associated with anastomotic stricture occurrence (P=0.016). However, the operative time, blood loss (>600 mL), surgical procedure, type of bilioenteric anastomosis, number of stitches and suture type did not reach statistical signif icance (Table 3). Finally, the incidences of all the possible postoperative risk factors of POPF, bile leak, surgical site infection, postoperative chemoradiation, postopera-tive biliary drainage or stenting, and hemorrhage were similar between patients with and without anastomotic stricture (Table 4).

Table 1. General patient characteristics

Table 2. Possible preoperative risk factors for anastomotic stricture

Table 3. Possible operative risk factors for anastomotic stricture

Table 4. Possible postoperative risk factors for anastomotic stricture

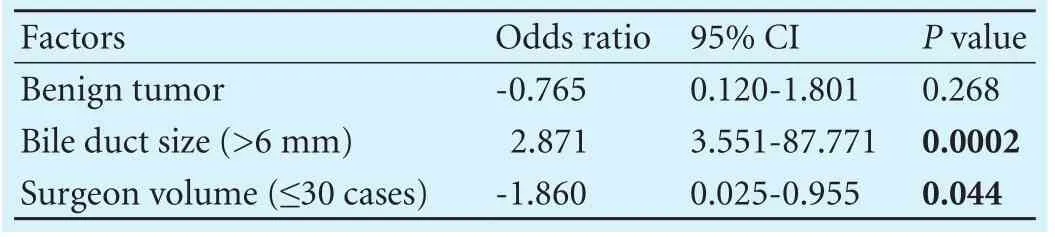

Logistic regression analysis

Using multiple logistic regression analysis, we found that surgeon volume (≤30 cases; OR: -1.860; 95% CI:0.025-0.955;P=0.044) was associated with the anastomotic stricture rate while bile duct size (>6 mm; OR:2.871; 95% CI: 3.551-87.771;P=0.0002) had a negative association (Table 5). However, benign tumor type could not be considered as a signif i cant independent risk factor (P>0.05).

Management and outcomes of anastomotic stricture

Thirty-two balloon dilations were performed in 18 patients, 9 biliary stentings in 6. Eight patients with anastomotic stricture were treated once, 9 patients twice, 4 patients three times. In total seventeen patients (17/21, 81.0%) were successfully managed with interventional therapy, but four patients (4/21, 19.0%) required reoperation.

In this study 6 patients with anastomotic stricture died, 3 due to tumor recurrence at the anastomosis, 2 because of distant metastasis and 1 with a benign tumor died of heart disease 13 months after repeated balloon dilation.

Among 15 survivors to date, fi ve had mild liver dysfunction and the rest had normal liver function, they were all free of fever and abdominal pain. The cumulative survival rate was 69.8% (Fig.).

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of independent risk factors for anastomotic stricture

Fig. The cumulative survival rate of patients with anastomotic stricture was 69.8%.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that anastomotic stricture is an uncommon complication following operation and anastomotic stricture can be treated primarily by interventional approaches. Reoperation remains the fi nal choice. Surgeon volume (≤30 cases) is a signif i cant risk factor for biliary stricture at the bilioenteric anastomosis, while bile duct size (>6 mm) may play a protective role.

Published articles on anastomotic stricture are few due to its low incidence and late development following operation,[6-11]Nevertheless, anastomotic stricture can signif i cantly affect quality of life and may even lead to life-threatening complications. Unfortunately, the risk factors for anastomotic stricture have not been well studied. Our analysis revealed that bile duct size was signif i cantly associated with anastomotic stricture incidence which is consistent with other studies.[6,10,11]In patients with a non-dilated bile duct, we routinely made it a sloped end or cut a slit in the anterior wall in an effort to expand the anastomotic size and facilitate the procedure. The results of this study, however, suggest that these methods failed to prevent anastomotic stricture. Of the patients with anastomotic stricture, three were confi rmed to have tumor recurrence at the anastomosis. We assume that the rest of the patients (18/21, 85.7%) with anastomotic stricture were due to benign perianastomotic fi brosis, which might explain how a dilated duct is protective against the complication.

Our results showed that the surgeon volume was related to anastomotic stricture. Surgeon-related factors for postoperative pancreatic fi stula have been discussed relative to pancreaticoduodenectomy,[15,16]yet a search of the literature did not fi nd the effect of surgeon volume previously described relative to anastomotic stricture. Although compared with pancreaticojejunostomy, bilioenteric anastomosis is less complicated, it is still a demanding technique according to our study. It even poses extra challenges to surgeons in the cases of non-dilated bile ducts or redoing bilioenteric anastomosis. We suggest several reasons that a surgeon’s inexperience performing the procedure could inf l uence the outcome. First, the arterial branches of the bile duct might be injured leading to bile duct ischemia and causing damage to the anastomosis. Second, improper surgical technique might be performed, such as an overly extensive dissection of periductal tissue or an excessive use of electrocautery for biliary duct bleeding control. Finally, these surgeons may prefer more stitches and apply more tension on the suture to prevent bile leak, especially in a case of a small duct. Hence, if bilioenteric anastomosis is performed by surgeons in their early training period (≤30 cases), they should be under the close guidance of experienced surgeons.

Other reported risk factors for anastomotic stricture include benign disease,[11]preoperative percutaneous biliary drainage and postoperative biliary stenting,[7]the number of anastomotic stitches and the placement of a biliary drainage stent.[13]These factors are, in essence, associated with bile duct size, yet they do not ref l ect the actual caliber. In our study, we found that 368 patients were diagnosed with bile duct size >6 mm, 273 patients had preoperative jaundice, and 77 patients were treated with preoperative biliary drainage or stenting. Hence, a large bile duct size is not necessarily associated with jaundice, and jaundice does not always necessitate biliary stenting or drainage. Similarly, benign tumors might be associated with bile duct dilation. Our study found that these factors did not signif i cantly affect the incidence of anastomotic stricture. In addition, biliary anatomy anomalies might contribute to the pathogenesis of anastomotic stricture, however, due to various reasons the factor was not assessed in this study.

In liver transplantation, inadequate arterial blood supply to the bile duct or hepatic arterial thrombosis,[17,18]and a high-tension anastomosis[19,20]had been reported to be associated with anastomotic stricture occurrence. In this study, these factors did not exist. No hepatic arterial reconstruction was performed, and more blood fl owed to the hepatic artery after ligation of the gastroduodenal artery. Although blood loss may cause anastomotic stricture, we did not fi nd a difference of blood loss between cases with and without anastomotic stricture. In addition, we isolated an adequate length of the upper jejunum in order to create a tension-free reconstruction.

In our study, anastomotic stricture was preferentially evaluated by interventional radiology with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, and managed with the placement of a biliary stent across the stricture, which is consistent with the literature.[6,7]Accordingly, 81.0% of the patients were managed successfully with biliary stenting and balloon dilation. There is currently no guideline that can identify high-risk patients who do not benef i t from stenting or dilation, therefore, four patients required reoperation after failure of repeated percutaneous dilatations. In patients with malignant tumors, anastomotic stricture caused by tumor recurrence was treated by stenting. The overall survival rate reached 69.8%. Our experience suggests that patient quality of life can be improved with prompt diagnosis and proper treatment.

Obviously, our data need further validation due to the small number of patients. The low incidence of anastomotic stricture makes it diff i cult to acquire larger cohorts, even though the study included data over a period of 10 years in our department. Furthermore, the results of the present study need to be conf i rmed by future multicenter studies, preferably with a prospective cohort study design.

Contributors: HQ proposed the study. ZJQ and LXL performed the research and wrote the fi rst draft. KJT, DHM, LHY and MJ collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. ZJQ and LXL contributed equally to the article. HQ is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471590, 81571554 and 81273270).

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital (2015-10-22-34).

Competing interest: No benef i ts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Hamad MA, El-Amin H. Bilio-entero-gastrostomy: prospective assessment of a modif i ed biliary reconstruction with facilitated future endoscopic access. BMC Surg 2012;12:9.

2 Tokodai K, Kawagishi N, Miyagi S, Nakanishi C, Hara Y, Fujio A, et al. Indications and outcomes of an endoscopic approach under laparotomy for the treatment of bilioenteric anastomotic strictures. Pediatr Transplant 2016;20:316-320.

3 Sanada Y, Mizuta K, Yano T, Hatanaka W, Okada N, Wakiya T, et al. Double-balloon enteroscopy for bilioenteric anastomotic stricture after pediatric living donor liver transplantation. Transpl Int 2011;24:85-90.

4 Chang JH, Lee I, Choi MG, Han SW. Current diagnosis and treatment of benign biliary strictures after living donor liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:1593-1606.

5 Barbier L, Souche R, Slim K, Ah-Soune P. Long-term consequences of bile duct injury after cholecystectomy. J Visc Surg 2014;151:269-279.

6 Duconseil P, Turrini O, Ewald J, Berdah SV, Moutardier V, Delpero JR. Biliary complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: skinny bile ducts are surgeons’ enemies. World J Surg 2014;38:2946-2951.

7 House MG, Cameron JL, Schulick RD, Campbell KA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, et al. Incidence and outcome of biliary strictures after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2006;243:571-578.

8 Reid-Lombardo KM, Ramos-De la Medina A, Thomsen K, Harmsen WS, Farnell MB. Long-term anastomotic complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy for benign diseases. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:1704-1711.

9 Röthlin MA, Löpfe M, Schlumpf R, Largiadèr F. Long-term results of hepaticojejunostomy for benign lesions of the bile ducts. Am J Surg 1998;175:22-26.

10 Tocchi A, Costa G, Lepre L, Liotta G, Mazzoni G, Sita A. The long-term outcome of hepaticojejunostomy in the treatment of benign bile duct strictures. Ann Surg 1996;224:162-167.

11 Malgras B, Duron S, Gaujoux S, Dokmak S, Aussilhou B, Rebours V, et al. Early biliary complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy: prevalence and risk factors. HPB (Oxford) 2016;18:367-374.

12 Singh DP, Arora S. Evaluation of biliary enteric anastomosis inbenign biliary disorders. Indian J Surg 2014;76:199-203.

13 Orii T, Karasawa Y, Kitahara H, Yoshimura M, Okumura M. Technical procedures causing biliary complications after hepaticojejunostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2014;61:1857-1862.

14 Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fi stula: an international study group (ISGPF) def i nition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13.

15 Noda H, Kamiyama H, Kato T, Watanabe F, Toyama N, Konishi F. Risk factor for pancreatic fi stula after pancreaticoduodenectomy performed by a surgeon during a learning curve: analysis of a single surgeon’s experiences of 100 consecutive patients. Hepatogastroenterology 2012;59:1990-1993.

16 Pecorelli N, Balzano G, Capretti G, Zerbi A, Di Carlo V, Braga M. Effect of surgeon volume on outcome following pancreaticoduodenectomy in a high-volume hospital. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:518-523.

17 Feier FH, Seda-Neto J, da Fonseca EA, Candido HL, Pugliese RS, Neiva R, et al. Analysis of factors associated with biliary complications in children after liver transplantation. Transplantation 2016;100:1944-1954.

18 Yildirim S, Ayvazoglu Soy EH, Akdur A, Kirnap M, Boyvat F, Karakayali F, et al. Treatment of biliary complications after liver transplant: results of a single center. Exp Clin Transplant 2015;13:71-74.

19 Mercado MA, Vilatobá M, Chan C, Domínguez I, Leal RP, Olivera MA. Intrahepatic bilioenteric anastomosis after biliary complications of liver transplantation: operative rescue of surgical failures. World J Surg 2009;33:534-538.

20 Nissen NN, Klein AS. Choledocho-choledochostomy in deceased donor liver transplantation. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:810-813.

Accepted after revision May 3, 2017

Imagination is more important than knowledge.

—Albert Einstein

July 15, 2016

Author Aff i liations: Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreaticosplenic Surgery, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100020, China (Zhu JQ, Li XL, Kou JT, Dong HM, Liu HY, Bai C, Ma J and He Q)

Qiang He, MD, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreaticosplenic Surgery, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 8 Gongtinan Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100020, China (Tel: +86-10-85231504; Fax: +86-10-85231503; Email:zack1234@163.com)

© 2017, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60033-X

Published online June 30, 2017.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Indocyanine green fl uoroscopy and liver transplantation: a new technique for the intraoperative assessment of bile duct vascularization

- Effects of multimodal fast-track surgery on liver transplantation outcomes

- Characteristics of recipients with complete immunosuppressant withdrawal after adult liver transplantation

- Predictive value of C-reactive protein/albumin ratio in acute pancreatitis

- Interaction between insulin-like growth factor binding protein-related protein 1 and transforming growth factor beta 1 in primary hepatic stellate cells

- Hepatopancreatoduodenectomy for advanced hepatobiliary malignancies: a single-center experience