影响Ⅳ型狼疮肾炎临床疗效的因素分析

2017-06-23张育榕漆媛媛马潇孟瑞霞杨艳王静

张育榕 漆媛媛 马潇 孟瑞霞 杨艳 王静

·论著·

影响Ⅳ型狼疮肾炎临床疗效的因素分析

张育榕 漆媛媛 马潇 孟瑞霞 杨艳 王静

目的 寻找目前常规治疗方案下,造成Ⅳ型狼疮肾炎(lupus nephritis,LN)患者治疗无效的临床风险因素。方法 纳入经肾脏穿刺病理活检确诊为Ⅳ型LN,经过激素及常规免疫抑制剂治疗并且随访超过6个月的患者198例,按照6个月后的治疗效果分为有效组(148例)和无效组(50例),从人口学特征(性别、年龄、SLE病程、LN病程),临床表现(面部红斑、盘状红斑、光过敏、血管炎、皮肤紫癫、雷诺征、口腔溃疡、发热、关节痛、浆膜腔积液、脱发、外周神经炎、淋巴结炎、高血压、恶性高血压、肉眼血尿等),实验室检查(血红蛋白、网织红细胞、白细胞、血小板、血白蛋白、球蛋白、血肌酐、尿素氮、血尿酸、三酰甘油、总胆固醇、尿蛋白定量、尿红细胞),自身抗体(抗核抗体,抗双链DNA抗体,抗心磷脂抗体,抗Sm,SSA,SSB,抗核糖体蛋白,抗中性粒细胞胞浆抗体等),病理学指标(袢坏死、白金耳、袢血栓、球形硬化比例、节段硬化比例、新月体比例、纤维性比例、间质急性病变、间质慢性病变、间质细胞浸润、膜性病变等),治疗方案及转归情况各个方面分析组间差异,使用Kaplan-Meier法筛选影响Ⅳ型LN临床疗效的风险因素,建立多因素COX回归模型分析其独立风险因素。结果 资料完整且规律随访的Ⅳ型LN患者共198例,无效组50例(占25.25%),有效组148例(占74.75%),2组诱导期治疗方案(单用激素,激素分别联合环磷酰胺、雷酚酸酯、FK506、环孢霉素A等)无统计学差异。进一步探究在常用治疗方案(激素及免疫抑制剂)下影响其疗效的风险因素发现,与有效组相比,无效组光过敏、肾功能异常、中等量蛋白尿、抗核糖体蛋白抗体阳性比例、肾小球球性硬化比例、慢性化指数(chronicity index,CI)、肾间质慢性化程度、肾间质细胞浸润程度及非炎症坏死性血管病变(non inflammatory necrotizing vasculopathy,NNV)比例明显增高(P<0.05)。Kaplan-Meier分析显示,肾功能异常、肾间质慢性化病变及间质细胞浸润的患者治疗无效率更高。建立多因素COX回归模型发现,起病时肾功能异常是LN临床疗效较差的独立风险因素。结论 对于常规诱导方案治疗的Ⅳ型LN,起病时肾功能异常的患者临床疗效差,同时抗核糖体蛋白抗体阳性及伴有肾间质慢性化病变、间质细胞浸润、NNV可能也是LN治疗反应较差的风险因素。

系统性红斑狼疮;狼疮肾炎;诱导治疗;风险因素

20世纪50年代糖皮质激素的使用对系统性红斑狼疮(systemic lupus erythematosus,SLE)的管理带来了深远的影响[1]。Pollak等[2]研究表明,在使用大剂量激素治疗狼疮肾炎(lupus nephritis,LN)后,增殖型LN患者的5年生存率提高至55%, 20世纪70年代随着细胞毒药物的使用,进一步延缓了LN患者终末期肾脏疾病(end-stage renal disease,ESRD)的进展[3]。由于激素联合环磷酰胺(cyclophosphamide,CYC)使LN患者的5年生存率上升至80%[4],激素联合CYC成为LN诱导治疗的经典方案。2000年左右,激素联合霉酚酸酯(mycophenolate,MMF)开始用于LN的诱导治疗,在ALMS这项大型的研究中,治疗6个月后,MMF与CYC展现出相似的缓解率[5-6]。自此开始,LN的疗效再未得到进一步提高,LN的治疗遭遇了瓶颈,12个月的完全缓解率也仅为10%~40%[7-8]。此后也有诸如他克莫司(tacrolimus,FK506)用于LN的诱导治疗,但均未显现出比CYC更好的疗效[9-10]。然而不管怎样,激素及自身免疫抑制剂[如CYC、MMF、FK506、环孢素(ciclosporin,CSA)等]仍然是LN重要的常规诱导方案,目前在此基础上的新的靶向治疗(如B细胞去除[11]、浆细胞抑制[12]、阻断共刺激通路[13]、I型干扰素抑制[14]及补体抑制等[15]),尚未展现出令人满意的效果。本研究则着力于分析常规治疗方案下影响Ⅳ型LN临床疗效的风险因素,对LN患者进行早期疗效判断,给予针对性治疗。

资料与方法

一、研究对象与分组

选择1998年4月1日至2013年4月30日在兰州大学第二医院住院且符合1997年修订的美国风湿病协会(American Rheumatism Association,ARA)的SLE诊断标准[16]、经肾活检诊断为Ⅳ型LN,具有完整的临床、病理及实验室检查记录且随访时间≥6个月的患者共198例,其中男27例,女171例,年龄10~69岁,平均年龄(30.3±9.8)岁。

将198例患者按照有无缓解分为有效组和无效组,无效组50例(占25.25%),男7例,女43例,有效组148例(占74.75%),男20例,女128例,其中CR组98例,PR组50例。有效组年龄范围10~53岁,平均年龄(29.6±9.7)岁;无效组年龄范围12~69岁,平均年龄(31.7±10.8)岁。

二、方法

分析统计2组人口学特征、临床表现、实验室检查、自身抗体学特征、病理学指标、治疗方案及转归情况,采用Kaplan-Meier法筛选与LN疗效有关的风险因素,进一步明确LN疗效的独立风险因素。

1.分析内容 对Ⅳ型LN患者分别收集下列资料:一般资料(性别、年龄、SLE病程、LN病程)、临床表现(面部红斑、盘状红斑、光过敏、血管炎、皮肤紫癜、雷诺征、口腔溃疡、发热、关节痛、浆膜腔积液、脱发、外周神经炎、淋巴结炎、高血压、恶性高血压、肉眼血尿等)、实验室检查[血红蛋白、网织红细胞、白细胞、血小板、血白蛋白(albumin,Alb)、球蛋白、血肌酐(SCr)、尿素氮(BUN)、血尿酸、三酰甘油、血总胆固醇、尿蛋白定量、尿红细胞]、免疫学指标[抗核抗体(antinuclear antibodies,ANA)、抗双链DNA抗体(A-dsDNA)、抗心磷脂抗体、抗Sm、SSA、SSB、抗核糖体蛋白(anti ribosomal protein,RNP)、抗中性粒细胞胞浆抗体、补体C3及C4、IgG]、病理学指标(袢坏死、白金耳、袢血栓、球形硬化比例、节段硬化比例、新月体比例、纤维性比例、间质急性病变、间质慢性病变、间质细胞浸润、膜性病变、IgG、IgA、IgM等),LN肾小球病理分型参照ISN/RPS2003分型方案[17],肾组织活动性指数(activity index,AI)、慢性化指数(chronicity index,CI)及血管病变分类参照文献评分[18-19]。

2.治疗方案 所有入选患者均接受激素和(或)免疫抑制剂治疗,其中诱导治疗包括单用激素,激素分别联合环磷酰胺、MMF、FK506、CSA等治疗。

3.疗效指标 ①完全缓解:24h尿蛋白定量≤0.4 g,且Alb及SCr均正常。②部分缓解:尿蛋白及SCr比基础值下降≥50%,且Alb≥30 g/L。③未缓解:尿检未改善或肾功能无好转(SCr增高或SCr下降未超过基础值的50%)[20-21]。有效组为治疗6个月后达到完全缓解或部分缓解,无效组为治疗6个月后仍是未缓解。

4.其他 ①大量蛋白尿:24h尿蛋白定量≥3.5 g;②中等量蛋白尿:24h尿蛋白定量≥1.0 g且<3.5 g,少量蛋白尿<1.0 g/24h;③低蛋白血症:Alb<35 g/L、肾功能异常、SCr>106 μmol/L。

三、统计学处理

采用SPSS 21.0软件进行统计学分析,计数资料以例(率)表示,呈正态分布的计量资料以均数±标准差表示,呈非正态分布的计量资料以M(1/4,3/4)表示。计数资料采用Pearsonχ2检验或Fisher精确检验比较组间差异。计量资料2组之间比较采用t检验,3组之间比较采用单因素方差分析,其中两两之间比较,方差齐时采用LSD检验,方差不齐时采用Kruskal-Wallis检验,等级资料采用秩检验。生存分析人存活终点事件为患者死亡,肾存活终点事件为发生ESRD。人、肾累积生存曲线及未缓解累积曲线采用Kaplan-Meier生存曲线估算,Log-rank检验比较组间差异,其中人、肾累积生存曲线时间为随访时间,未缓解累积曲线时间为部分缓解时间。采用Kaplan-Meier法筛选与LN疗效有关的风险因素,建立多因素COX回归风险模型筛选出LN疗效的独立风险因素。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结 果

一、患者一般情况

有效组148例,男20例,女128例;无效组50例,男7例,女43例。有效组起病年龄(25.9±9.8)岁,无效组起病年龄(27.4±10.4)岁。有效组SLE病程23个月,无效组24个月。有效组LN病程8个月,无效组12个月。

二、不同的诱导期治疗方案对LN疗效的影响

有效组和无效组的诱导期治疗方案无统计学差异(P>0.05)。Kaplan-Meier分析显示,各诱导期治疗方案之间累积无效率无统计学差异(P>0.05),需更进一步探讨常规治疗方案下影响Ⅳ型LN患者疗效的其余因素。(表1)

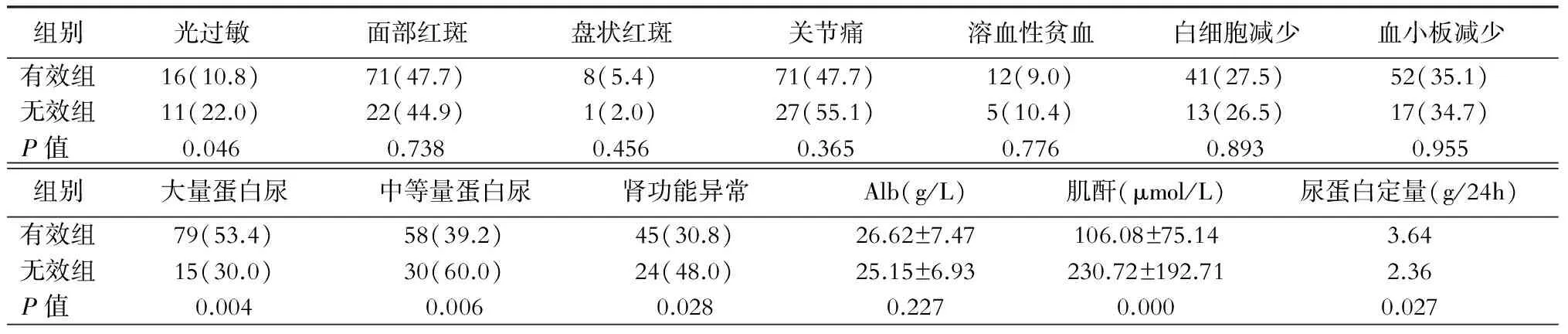

三、起病时不同的肾外及肾脏表现、实验室检查对LN疗效的影响

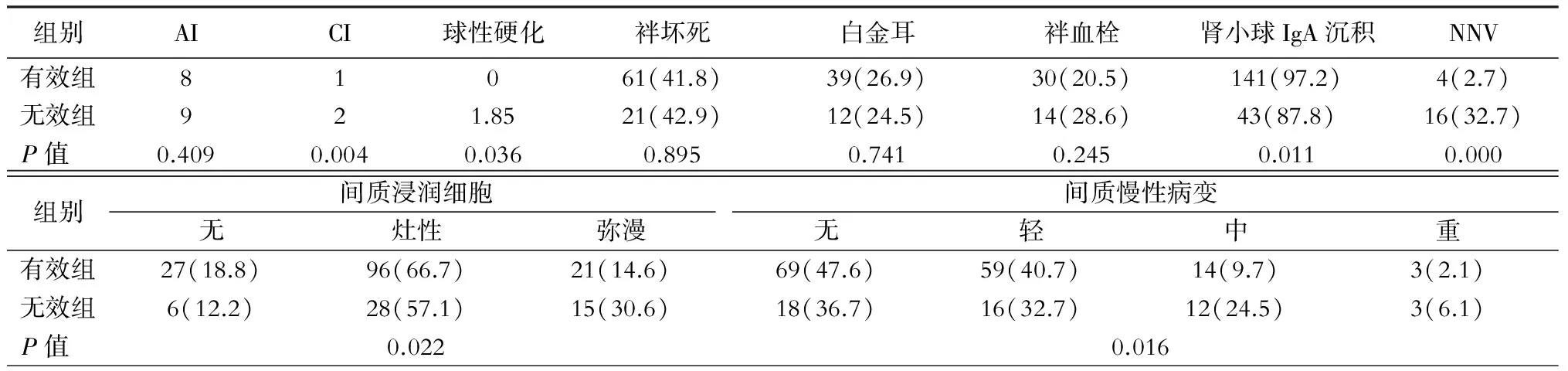

与有效组相比,无效组患者光过敏、肾功能异常及中等量蛋白尿的比例均增高(P<0.05),此类患者SCr水平较高(P<0.05),见表2。Kaplan-Meier分析显示,肾功能异常组的患者治疗无效率增高(Log RankP=0.007),见图1。

表1 有效组与无效组诱导治疗方案的比较[例(%)]

表2 2组患者临床表现、实验室检查指标的比较[例(%)]

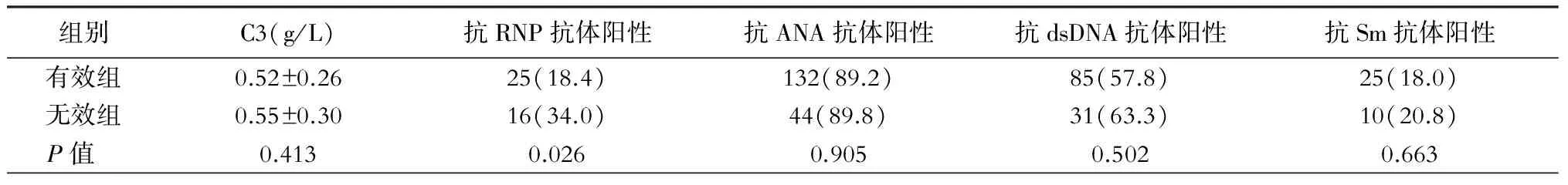

四、起病时不同的血清自身抗体谱对LN疗效的影响

与有效组相比,无效组患者抗RNP抗体阳性比例明显增高(P<0.05),其余抗体未见明显统计学差异(表3)。Kaplan-Meier分析显示,抗RNP抗体阳性组与阴性组累积无效率无差异。

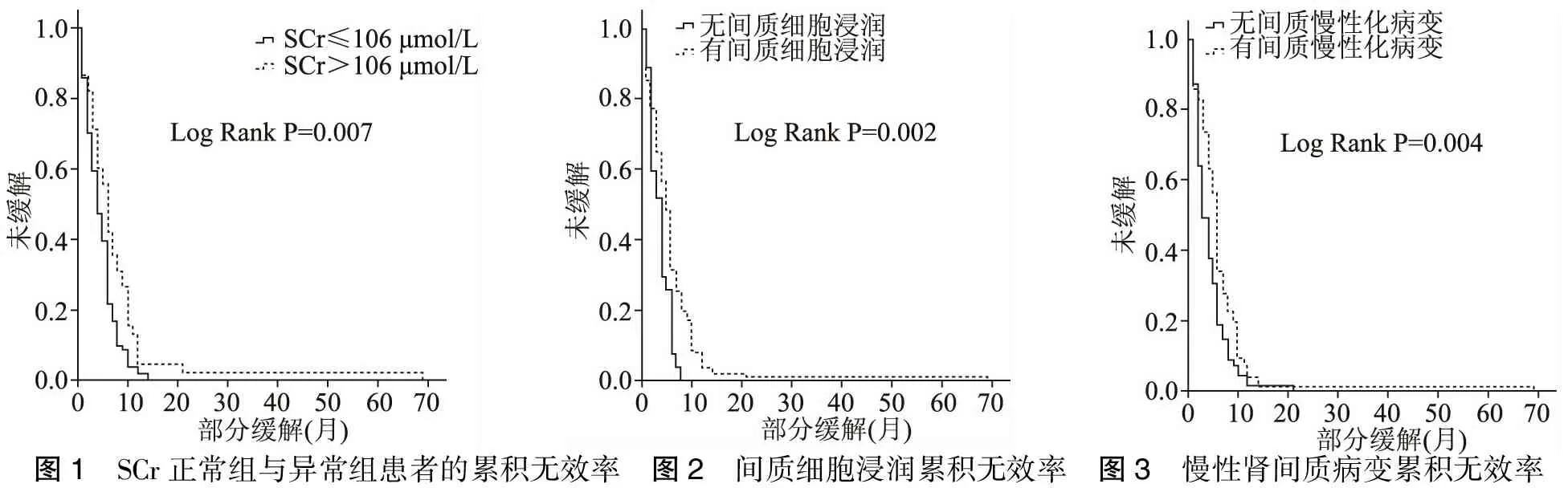

五、起病时不同的肾脏组织学病理损害对LN疗效的影响

与有效组相比,无效组患者肾小球球性硬化比例、CI、肾间质慢性化程度、肾间质细胞浸润程度及血管非炎症坏死性血管病变(NNV)比例明显增高(P<0.05),肾小球IgA沉积比例降低(P=0.011)(表4)。Kaplan-Meier分析显示,肾间质慢性化病变及间质细胞浸润患者治疗无效率增高。(表4,图2~3)

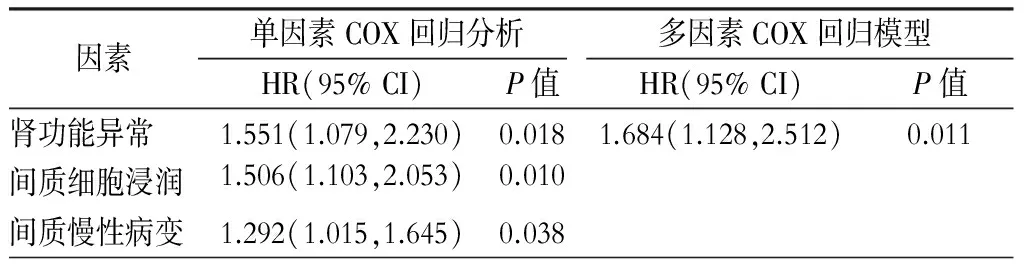

六、单因素及多因素COX回归分析Ⅳ型LN患者疗效不佳的临床风险因素

单因素COX回归显示,起病时肾功能异常、间质细胞浸润、间质慢性病变是Ⅳ型LN治疗无效的风险因素。多因素COX回归风险模型显示,起病时肾功能异常是Ⅳ型LN治疗无效的独立风险因素。(表5)

表5 单因素及多因素COX回归分析Ⅳ型LN疗效的风险因素

讨 论

尽管在过去的50年中,激素及免疫抑制剂作为LN的常规治疗方案很大程度上提高了LN的疗效,但是从2000年开始,LN的疗效再未得到进一步的提高,LN的治疗遭遇了瓶颈。常规治疗方案的疗效可能受到以下因素的影响:免疫抑制剂药物的选择和搭配、药物的剂量、诱导期治疗的时间、用药人群的种族差异以及患者的依从性和医保支持力度、患者的病情等[22]。

表3 2组患者血清自身抗体谱的比较[例(%)]

表4 2组患者肾脏病理损害的比较[例(%)]

图1 SCr正常组与异常组患者的累积无效率 图2 间质细胞浸润累积无效率 图3 慢性肾间质病变累积无效率

本研究发现,治疗无效的患者起病时的血肌酐水平往往都较高,肾功能异常的比例明显增高,肾功能异常是其疗效不佳的独立风险因素。戚超君等[23]研究也展现出同样的结果,增殖型及膜性LN患者在常规治疗方案治疗下,治疗无效的患者其起病时SCr水平较高。在LN患者治疗初期,存在肾功能异常的患者,其未来可能对常规治疗反应较差。大量蛋白尿一直都是肾脏疾病患者预后不良的临床风险因素之一[24],然而我们的研究发现表现为中等量蛋白尿的Ⅳ型LN患者却对常规治疗方案的治疗反应最差,而大量蛋白尿的患者反而治疗效果优于前者。患者在治疗初期的蛋白尿的水平能否作为疗效判断的考量指标,尚需要进一步的观察。

LN患者起病时肾脏病理的损害情况对治疗反应有一定的影响。肾间质慢性化病变不仅是肾脏预后不良的风险因素,也是患者对常规治疗方案不敏感的原因之一[25],本研究也进一步证实了这一观点。以往文献报道,肾间质细胞浸润与患者起病时的血肌酐水平及肾间质慢性化病变的指数呈正相关[26]。本研究也发现,肾间质细胞浸润的患者治疗反应差。血管病变在LN患者中并不少见,对患者预后具有一定的影响,尤其NNV及血检性微血管病变的患者预后恶劣,不仅如此,伴有上述两种血管病变的患者对常规的免疫抑制治疗疗效欠佳[19,27]。本研究也进一步证实伴有NNV血管病变的Ⅳ型LN患者治疗反应差。在LN患者的治疗中,需要重视肾小管间质病变及血管病变对治疗反应的影响。LN患者在起病时表达的不同类型的抗体可能对疗效有一定的影响。本研究发现,治疗无效组抗RNP抗体阳性的比例明显高于有效组,提示抗RNP抗体阳性的Ⅳ型LN患者可能对常规治疗反应差。抗RNP抗体属于RNA抗原相关的抗体,其靶抗原是细胞内不同功能的RNA与相应蛋白结合而成的复合体,参与mRNA转录后的剪切加工过程。抗RNP抗体其抗原的核心是u1RNP。研究表明,抗u1RNP抗体对混合型结缔组织病的诊断具有特异性,在20%~30%的SLE患者中也有表达,与雷诺现象及肾脏损伤有关[28]。Weckerle等[29]研究表明,抗RNP抗体与SLE患者血清增高的干扰素α(interferon-alpha,IFN-α)有关。IFN-α是与SLE相关的最重要的I型IFN,参与了SLE的发病过程[30],与SLE患者的病情活动及严重程度密切相关,进一步阐明抗RNP抗体与IFN-α的关系在LN发病机制中的作用,可能为LN的靶向治疗提供思路。常规治疗方案中包含的免疫抑制剂特异性低,靶向差,不良反应居多[31],这也是目前治疗LN遭遇瓶颈的重要原因。长期以来,基于LN发病机制的精准靶向治疗的研究一直都是LN治疗学的重点[32]。也只有如此,不仅能有望突破LN治疗目前的瓶颈,而且对能够早期判断LN疗效的无创的、特异性的标记物的研发也大有裨益。

[1] Heller BI, Jacobson WE, Hammarsten JF. The effect of cortisone in glomerulonephritis and the nephropathy of disseminated lupus erythematosus[J]. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine, 1951, 37(1): 133-142.

[2] Pollak VE, Pirani CL, Schwartz FD. The natural history of the renal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 1997, 8(7): 1189-1198.

[3] Austin HA, Klippel JH, Balow JE, et al. Therapy of lupus nephritis: controlled trial of prednisone and cytotoxic drugs[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 1986, 314(10): 614-619.

[4] Ginzler EM, Bollet AJ, Friedman EA. The natural history and response to therapy of lupus nephritis[J]. Annual review of medicine, 1980, 31: 463-487.

[5] Costenbader KH, Desai A, Alarcon GS, et al. Trends in the incidence, demographics, and outcomes of end-stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis in the US from 1995 to 2006[J]. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 2011, 63(6): 1681-1688.

[6] Dooley MA, Jayne D, Ginzler EM, et al. Mycophenolate versus azathioprine as maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2011, 365(20): 1886-1895.

[7] Tektonidou MG, Dasgupta A, Ward MM. Risk of end-stage renal disease in patients with lupus nephritis, 1971-2015: a systematic review and bayesian meta-analysis[J]. Arthritis& rheumatology, 2016, 68(6): 1432-1441.

[8] Parikh SV, Rovin BH. Current and emerging therapies for lupus nephritis[J]. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN, 2016, 2(5): 9-20.

[9] Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period: a comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1,000 patients[J]. Medicine, 2003, 82(5): 299-308.

[10]Danila MI, Pons-Estel GJ, Zhang J, et al. Renal damage is the most important predictor of mortality within the damage index: data from Lumina LXIV, a multiethnic US cohort[J]. Rheumatology, 2009, 48(5): 542-545.

[11]Rovin BH, Dooley MA, Radhakrishnan J, et al. The impact of tabalumab on the kidney in systemic lupuserythematosus: results from two phase 3 randomized, clinical trials[J]. Lupus, 2016, 5(14): 1597-1601.

[12]Alexander T, Sarfert R, Klotsche, et al. The proteasome inhibitior bortezomib depletes plasma cells and ameliorates clinical manifestations of refractory systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 2015, 74(7): 1474-1478.

[13]Shock A, Burkly L, Wakefield I, et al. CDP7657, ananti-CD40L antibody lacking anFc domain, inhibits CD40L-dependent immune responses without thromboticcomplications: an in vivo study[J]. Arthritis research&therapy, 2015, 17: 234.

[14]Peng L, Oganesyan V, Wu H, et al. Molecular basis for antagonistic activity of anifrolumab, an anti-interferon-alpha receptor 1 antibody[J]. Mabs, 2015, 7(2): 428-439.

[15]Barilla-Labarca ML, Toder K, Furie R. Targeting the complement system in systemic lupus erythematosus and other diseases[J]. Clinical immunology, 2013, 148(3): 313-321.

[16]Hochberg MC. Updating the American college of rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Arthritis and rheumatism, 1997, 40(9): 1725.

[17]Weening JJ, D'Agati VD, Schwartz MM, et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited[J]. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN, 2004, 15(2): 241-250.

[18]Austin HA, Muenz LR, Joyce KM, et al. Diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis: identification of specific pathologic features affecting renal outcome[J]. Kidney international, 1984, 25(4): 689-695.

[19]Wu LH, Yu F, Tan Y, et al. Inclusion of renal vascular lesions in the 2003 ISN/RPS system for classifying lupus nephritis improves renal outcome predictions[J]. Kidney international, 2013, 83(4): 715-723.

[20]Plastiras SC, Karadimitrakis SP, Kampolis C, et al. Determinants of pulmonary arterial hypertension in scleroderma[J]. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism, 2007, 36(6): 392-396.

[21]Li M, Wang Q, Zhao J, et al. Chinese SLE teatmentand research group(CSTAR) registry: II. prevalenceand risk factors of pulmonary arterial hypertension in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Lupus, 2014, 23(10): 1085-1091.

[22]Hoover PJ, Costenbader KH. Insights into the epidemiology and management of lupus nephritis from the US rheumatologist's perspective[J]. Kidney international, 2016, 90(3): 487-492.

[23]戚超君, 叶彬娴, 倪兆慧, 等. 增殖型和膜型狼疮性肾炎患者缓解及复发的相关因素四年随访研究[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2013, 93(48): 3826-3830.

[24]Kono M, Yasuda S, Kato M, et al. Long-term outcome in Japanese patients with lupus nephritis[J]. Lupus, 2014, 23(11): 1124-1132.

[25]Yu F, Wu LH, Tan Y, et al. Tubulo interstitial lesions of patients with lupus nephritis classified by the 2003 International Society of Nephrology and Renal Pathology Society System[J]. Kidney International, 2010, 77(9): 820-829.

[26]Hsieh C, Chang A, Brandt D, et al. Predicting outcomes of lupus nephritis with tubulointerstitial inflammation and scarring[J]. Arthritis care&research, 2011, 63(6): 865-874.

[27]王静, 胡伟新, 陈惠萍, 等. Ⅳ型狼疮性肾炎伴血栓性微血管病变的临床特点及预后[J]. 肾脏病与透析肾移植杂志, 2007, 16(4): 322-328.

[28]Carpintero MF, Martinez L, Fernandez I, et al. Diagnosis and risk stratification in patients with anti-RNP autoimmunity[J]. Lupus, 2015, 24(10): 1057-1066.

[29]Weckerle CE, Franek BS, Kelly JA, et al. Network analysis of associations between serum interferon-alphaactivity, autoantibodies, and clinical features in systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Arthritis and rheumatism,2011, 63(4): 1044-1053.

[30]Reizis B, Colonna M, Trinchieri G, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: one-trick ponies or workhorses of the immune system?[J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2011, 11(8): 558-565.

[31]Schwartz N, Goilav B, Putterman C. The pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of lupus nephritis[J]. Current opinion in rheumatology, 2014, 26(5): 502-509.

[32]苏军霞, 梁昭红, 刘天喜, 等. 狼疮性肾炎患者尿单核-巨噬细胞趋化蛋白-1和转化生长因子-β1检测的临床意义[J]. 兰州大学学报(医学版), 2009, 35(3): 68-71.

Risk factors influencing curative effect of class Ⅳ lupus nephritis

ZHANGYu-rong,QIYuan-yuan,MAXiao,MENGRui-xia,YANGYan,WANGJing.

DepartmentofNephropathy,LanzhouUniversitySecondHospital,Lanzhou730030,China

WANGJing,E-mail:xiaoyu123226@hotmail.com

Objective To investigate the clinical risk factors for unresponsive common approaches on the treatment of class IV lupus nephritis(LN).Methods The class IV LN patients were confirmed by renal biopsy, treated with glucocorticoid and common immunosuppressive agents and followed up for more than 6 months. They were divided into two groups according to curative effect after treatment for 6 months. The differences between the two groups were analyzed by means of demographic characteristics, clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, autoantibodies, pathologic indicators, treatment regimens and outcomes. The possible influencing risk factors on the class Ⅳ LN were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier, and the independent risk factors were analyzed by multivariate COX regression modeling.Results A total of 198 patients with complete data and regularly followed-up were enrolled. They were divided into two groups: 50(25.25%) patients in non-response group and 148(74.75%) in response group. There was no significant difference between two groups in responsive rate under various common induction therapies. And then, the risk factors influencing the curative effects of class LN Ⅳ patients were further explored. Results showed that the nonresponse group had a higher rate of photosensitization, renal dysfunction, moderate proteinuria, the anti-RNP positive, renal glomerular sclerosis, CI, chronic interstitial lesions, interstitial cellular infiltration and NNV than in the response group(P<0.05). Kaplan-Meier results showed that a decreasing response happened in the group with a higher rate of renal dysfunction, chronic lesions and interstitial cellular infiltration(Log RankP<0.05). Then multivariate COX regression model investigated that renal dysfunction was an independent risk factor for poor curative effect.Conclusions Under the treatment of common induction therapy, the class Ⅳ LN patients with baseline renal dysfunction have a terrible curative effect. In addition, it is possible that the baseline anti-RNP positivity, chronic interstitial lesions, interstitial cellular infiltration or NNV are the risk factors for unresponsive treatment.

Systemic lupus erythematosis; Lupus nephritis; Induction therapy; Risk factors

10.3969/j.issn.1671-2390.2017.05.002

国家自然科学基金(No.81100521);高等学校博士学科专项科研基金(No.902000-040701/902000-040752)

730030 兰州,兰州大学第二医院肾病科(张育榕,漆媛媛,马潇,孟瑞霞,杨艳,王静);张育榕和漆媛媛为共同第一作者

王静,E-mall:xiaoyu123226@hotmail.com

2016-11-17

2017-04-06)