头顶或足下

2017-04-06张利ZHANGLi

张利/ZHANG Li

头顶或足下

张利/ZHANG Li

Over Our Heads or Under Our Feet

屋顶是我们熟知的基本建筑要素,它与四壁一起构成对建成空间的起码包被,在“遮风蔽雨”方面扮演着建筑史上最持之以恒的角色。

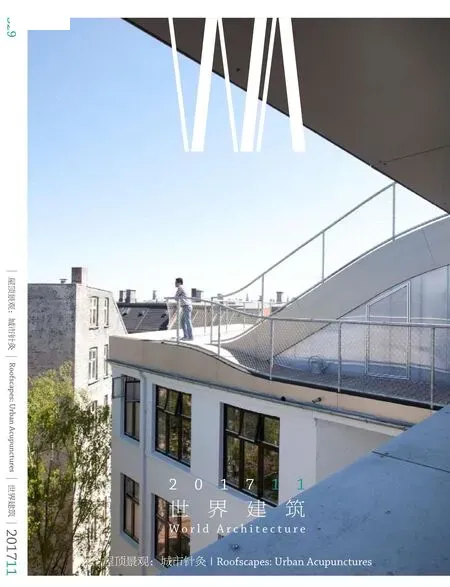

人与屋顶的故事在很长时间内保持了一种不变的空间关系的设定:即屋顶高悬在我们的“头顶”,居高临下,不怒自威,保持一种莫名的尊崇与距离感。我们充其量是通过阁楼或老虎窗战战兢兢地试图在局部上改变屋顶的性格。不过到了工业革命以后,随着平的上人屋顶的普及,屋顶开始从我们的“头顶”降落到了我们的“足下”,“威严”不再,而是作为一种富含公共性潜能的场所而受到越来越多的建筑师的青睐。本期的《世界建筑》正是在特邀编辑、意大利建筑师及学者安布罗西尼的带领下,对屋顶作为多功能使用空间的类型学进行一次审视。

我们必须承认的是,屋顶从“头顶”到“足下”的改变,在建筑学上的意义不仅仅是类型与形式的,更是空间价值观的。从某种程度上说,“屋顶观”是“建筑观”最直接的呈现。

在前工业时期,无论是西方还是东方,屋顶都不约而同地成为建筑的最重要的意义载体,指向一种表义屋顶的屋顶观。不难想像,作为房屋本体与天空的界面,作为俯瞰众生的高空遮蔽,以及作为在技术欠发达时代建造工程的最复杂也是最关键的成就,屋顶被有意无意地列为崇拜的对像而被赋予大量的意义是很自然的。从外面看,屋顶的轮廓线与质感的组合构成表义的句法,昭示建造者所属群体的价值观。佛罗伦萨圣母百花大教堂的穹顶、伦敦议会大厦的尖顶,以及遵化清东陵的多条指向背后山脊的自隆恩殿至明楼的屋顶轴线,皆是阅读其所处时代的群体信念的范本。而从内部看,屋顶天花的符号学则更是直白(甚至是冗余)表义的集结,成为建筑学、符号学与象征学爱好者的共同天堂。这种表义屋顶的传统一直延续到现代高密度城市形成的初期,曼哈顿早期以帝国大厦和克莱斯勒大厦为代表的高层建筑的顶冠之争便是例子。自20世纪后期起,新一波象征意义屋顶的潮流似乎卷土重来。这一次是借着建筑的“后现代”之风(或说,庸俗的历史主义之风)以及毫不遮掩的商业化,而其所占领的则多是新兴经济体的快速形成中的都市。无论如何,在此一个不变的主题是,表义屋顶永远把屋顶置于所有的人的头顶,因凌驾之势而就崇拜之举,这种屋顶观恐怕要继续在建筑的发展故事上伴随我们一大段时间。

工业化时期,与阿尔多·罗西所指出的“天真的功能主义”相伴,造就了一种把各种机械设备放置于屋顶的常规,指向一种令人啼笑皆非的技术屋顶的屋顶观。各种为职业建筑师编制的指南对屋顶上必须占用的机械面积津津乐道,各种建筑技术规范毫无顾忌地对管道必须突出屋顶的高度做出得寸进尺的要求。从VIV空调机组,到太阳能集热器,到卫生间的排气管,到厨房的烟囱,在机械化理性的推动下迅速控制了普通现代城市建筑的天际线。这种屋顶观原本的逻辑是屋顶高高在上,所以在城市中是看不见的;但讽刺的是,现代城市高层建筑的此起彼伏恰恰使这种技术屋顶成为最可视的城市景观——当然,也是最丑陋的城市景观。时至今日,我们仍然不时在城市管理与工程实践领域遇到这种技术屋顶观的强烈拥趸者,所幸的是他们的数量正在越变越少。

后工业时期带来了一种真正革命性的屋顶观,虽然它所反映的是勒·柯布西耶或安东尼·高迪早年的先驱性实验,但确实是在后工业城市中才开始形成真正的公共生活效果。它把屋顶的定位从“头顶”移至“足下”,戏剧性地增强大型公共建筑屋顶的公众可达性,使屋顶成为城市生活的平台,指向一种令人振奋的广场屋顶的屋顶观。在意识形态上它是更公平、更公民化的城市生活的直译,在空间类型学上它把屋顶从“第五立面”变为“第三地面”(第一为城市地面,第二为城市空中步道)。我们在斯诺赫塔事务所的大型文化建筑中看到这一潮流的启始,在21世纪落成的一系列城市公共建筑案例中看到它的延伸与跃动。它在新的技术与文化背景下激进地将勒·柯布西耶的纪念性与公共性加以融合,用观景台、巨型坡面、空中花园等原型来重新定义国际城市中重要公共建筑的屋顶,造就了为我们所熟悉的以承载城市多样化生活为诉求的一系列佳作。类似的,用聚落原型对普通建筑的屋顶进行人性化是对上述潮流在非高显现度城市建筑——特别是居住建筑——上的补充,也是对柯布、高迪都曾尝试过的乌托邦社区理想的现实主义的诠释,它或许对我们中国当代城市的品质进化更具参考意义。无论如何,我们期待平台屋顶的人性化元素在我们的城市中更加深入人心,不管是在高可视度的公共建筑,还是在普通人日常的居住建筑中。

感谢古斯塔夫·安布罗西尼的客座编辑,是他卓越的研究工作使本期《世界建筑》成为可能。□

Roof is an architectural element that we are well aware of.Together with the walls, it completes the basic envelope of the built space. It certainly continues to perform the key role in providing shelter.

For a long time, there had been an assumption regarding the relation between the roof and the human body: it is over our heads.With that exclusive position, the roof enjoys a commanding pose and all associated feelings coming from us the human beings that may well be defined as admiration or even worship. Only through the triviality of penthouses and dormer windows have we tried to touch the myth of the roofs. Industrialisation however, changed everything. Through the new flat, accessible roofs, the roof gradually changed its position,from over our heads down to under our feet. Most of its monumental features are replaced by public activities. The roof is starting to pose itself as a new typology with serious public potentials, catching the attention of architects from all around the world. In this edition of World Architecture, we are going to have a tour of this new typology, under the guide of our guest editor, Professor and Architect Gustavo Ambrosini.

Regarding the roof changing from over our heads to under our feet, there is one thing we have to make clear: such a change is not only typological, it is also ideological. The view you take at the roof eventually ref l ects the view you take at the world.

In pre-industrial times, both in the East and the West, the roof had become a key carrier of symbolic meanings. Symbolic roofs was the dominating idea about the roof. It is quite understandable that at a time of low technological capabilities, with its physicality hanging high above, overlooking everyone below and manifesting the highest possible construction achievement, the roof had to be associated with a lot of symbolic meanings. From the outside, the profile and the texture of the roof forms the syntax of collective value expression. Be it the dome of the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore, the spike of the British Parliament, or the axial sequence of the Zunhua Qing Tombs,the roof unmistakably presented the belief of the community by whom it was built. From the inside, decorations in the ceiling became the detailed, if not redundant, collection of symbols, entertaining architects, semiologists and symbolists alike. The tradition of symbolic roofs has extended far beyond the turn of the twentieth century. The beauty contest between the Empire State and the Chrysler in early Manhattan was just one of many similar stories. Even after the turn of the twenty-first century, symbolic roofs have launched yet another wave of offensive quite unexpectedly, this time mainly in capitals of emerging economies, accompanied by the vulgarity of Post-Modernism and the brutality of shameless commercialism. It is fair to say that whether you like it or not, symbolic roofs will be around for a while.

At the peak of industrialisation, with the rise of "naïve functionalism" stated by Aldo Rossi, the roof (usually flat and surrounded by tall parapets) became a dump yard for unwanted mechanics. This led to an appalling view to the roof: mechanics roofs. Not only practical guides to architects have listed all kinds of mechanical components to be put onto the roof, but also building codes and regulations forcing architects to let mechanics penetrating the roof by large quantities. This mechanical rationality soon enabled ugly roofs dominating the skies of modern cities. Ironically, the original idea that roofs could hide all those unwanted gadgets was based upon the invisibility of the top surface of the roofs. Yet it is exactly industrialisation that had made our cities taller and taller, exposing more and more of the roofs. Today, it is not difficult to meet one or two city administrators or engineers who are still in awe of mechanics roofs. Fortunately, their number is shrinking.

It is post-industrialisation that finally brought about the real revolution in roofs. The revolution may ref l ect some early pioneering experiments by those of Le Corbusier and Antonio Gaudi, but it is in the post-industrial cities that the idea materialised into true public life. The roof is no longer over our heads, but under our feet. Public accessibility to the roof is dramatically improved, making the roof practically a theatre of human activities. This is the idea of piazza roofs, the new typology that regards the roof as the third ground(after the urban ground and the sky walk) rather than the fifth façade,and takes the democratisation of urban space in the air as the only priority. Through the works of offices like Snøhetta, we witness a trend that is now spreading over major culture facilities around the world. They combine the use of form and the provision of public space,redefining the roof vocabulary with look-out decks, giant slopes, or floating gardens. Most of the products of this trend are highly visible urban entities. In contrast, there is also another trend taking at the less visible urban artefacts such as residential blocks, which too democratises roofs, albeit through fractal small scale interventions inspired by traditional villages. Comparing with the former one, the latter trend might be even more useful to contemporary Chinese cities,where it is the generic buildings, not the high profiles ones, that are crying out for quality improvements.

We have to give special thanks to our guest editor, Professor Gustavo Ambrosini. It is his exceptional research that makes this edition of World Architecture possible.□

清华大学建筑学院/《世界建筑》

2017-11-11